Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Subjectivity in Troubadour Poetry

- Part II The ‘Chansons de geste’ in the Age of Romance: Political Fictions

- Part III Courtly Contradictions: The Emergence of the Literary Object in the Twelfth Century

- Part IV The Place of Thought: The Complexity of One in French Didactic Literature

- Part V Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry

- Part VI Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries

- Afterword

- General Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- Bibliography of Work by Sarah Kay

- Index

- Gallica

At the Bleeding Edge of Courtly Love

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

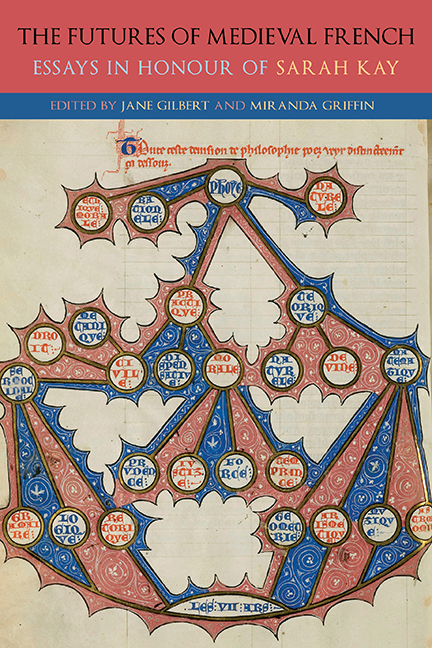

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Subjectivity in Troubadour Poetry

- Part II The ‘Chansons de geste’ in the Age of Romance: Political Fictions

- Part III Courtly Contradictions: The Emergence of the Literary Object in the Twelfth Century

- Part IV The Place of Thought: The Complexity of One in French Didactic Literature

- Part V Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry

- Part VI Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries

- Afterword

- General Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- Bibliography of Work by Sarah Kay

- Index

- Gallica

Summary

What news from the bleeding edge of courtly love?

IT IS ONE of the most memorable scenes in the corpus of Arthurian romance: having just avenged his cousin Calogrenant's shame by mortally wounding the guardian of the mysterious fountain in the forest of Brocéliande, the knight Yvain gives chase. Driven mainly by concern for his reputation – he hopes to retain sufficient proof of his victory to silence the mockeries of a sardonic Keu – Yvain goes so far as to follow the dying knight into his otherworldly castle, becoming trapped inside. Just as the situation is looking grim, with the lord dead and his men out for revenge, a woman named Lunete repays a past kindness by giving Yvain a magic ring that hides him from their searching eyes. The intruder can now marvel at the beauty of the castle's grieving widow from a point of safety. Despite his invisibility, however, he does not go unremarked. The occupants know that Yvain is among them: the slain guardian's wounds continue to bleed, a marvel interpreted as certain proof that the killer remains present at the scene.

In Courtly Contradictions, a sustained study of the role played by contradiction in structuring both the production and reception of works of ‘courtly’ literature, Sarah Kay reads this scene in terms of the surprising affinity that it suggests between the sublime and the perverse. Kay sets her analysis against the backdrop of courtly texts’ reception within Lacanian psychoanalytic discourse: Jacques Lacan argues that courtly love (l’amour courtois) plays a foundational role in the modern subject's desiring experience, and Slavoj Žižek cites Lacan's account approvingly. However, Kay notes, a kind of contradictoriness seems at the same time to oppose these thinkers’ rhetoric. For Lacan, courtly love exemplifies sublimation: the delay of sexual gratification and the redirection of its associated energy to other ends. In Žižek's appraisal, courtly love corresponds instead to perversion, which implies precisely the sort of release of the sexual drive that sublimation would preclude (259–60).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Futures of Medieval FrenchEssays in Honour of Sarah Kay, pp. 150 - 165Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021