The town “seems [like] a city of my youth … a place I had read of in some old book. The streets are dim and our own house is fading from my memory; but the names of those we love are all on our hearts.”

On the afternoon of 18 July 1855 the citizens of Dubuque, Iowa and the excursionists who had arrived at Dunleith, Illinois across the Mississippi River the evening before, gathered at a “sumptuous,” “barbeque” picnic on a hill above town to celebrate the completion of the Illinois Central Railroad to Dunleith. Many celebrated the day as Dubuque’s “new birthday” as the future great emporium of the northwest. For many old settlers the “railroad festival” marked “one of the brightest days” in the “triumphant progress” of their “beloved city of the mines.” Caught up in the regional mania among boosters in every larger town and city to inaugurate the arrival of the railroad with an “excursion” and celebration, Dubuque boosters had made the call for a “festival” months before and formed committees to make arrangements and to write to dignitaries and friends from around the country to invite them to come. The Arrangements Committee drew from a range of standard practices at recent excursions, banquets, political canvasses, and “barbecues” to organize the excursion. So too, the Committee of Correspondence, which included political rivals George Wallace Jones and Judge Thomas S. Wilson in a rare show of unity, sent letters of invitation to “many distinguished strangers” around the country. Stephen A. Douglas, U. S. Senator from Illinois who had pushed through the Illinois Central Act that designated Dubuque as the western terminus of the road, agreed to break his summer leave and come. For boosters, a successful “festival” would sanction their leadership and signal Dubuque’s emergence as a true “hometown” where they could live a full middle-class life locally, regionally, and nationally.

For the most part, the boosters of Dubuque succeeded. “Almost everyone in town” gathered at the wharf to greet the visitors and excursionists ferried over from Dunleith that morning. They did this, in spite of knowing that the day had already begun badly and been “marred” when a “frightful accident” during the gun salute at dawn from the bluffs left James Best’s right arm and left hand badly mangled. They then formed a grand procession up Main Street. The Masons, Odd Fellows, city and county officials, workers, and others carried banners and placards that proclaimed this great achievement and its promise of hope for the town. After marching up the bluffs, they gathered on a grove on West’s hill above the lower town. They all took their seats at long tables. Lincoln Clark, a former judge and local lawyer, greeted the crowd and introduced several speakers. The food and beverages, including – in spite of protest – liquor, carried to the site in wagons, formed a “sumptuous” several course banquet. No expense was spared.

As in most excursions, after the “ladies” retired to escape the late afternoon sun, the banquet turned into a rowdy male event. Numerous toasts were made and drunk to, amid a certain amount of rowdy boyish behavior by dignitaries and locals alike. Stephen A. Douglas, the “Little Giant,” was the “Lion of the day.” Sharing the spotlight was George Wallace Jones, Dubuque’s hometown U. S. Senator since 1848 and the “patriarch” of the local Democratic Party and, indeed, town society. It was Jones who had convinced Douglas in 1850 to make Dunleith, across from Dubuque, the terminus of the railroad and had been instrumental in forming the Dubuque and Pacific Railroad, its grand name expressing the boosters’ transcontinental ambitions. After the speeches, the banquet gradually dispersed into various gatherings down on Main Street. Most boosters were pleased that the event had come off so well and that the townspeople had come together in a show of unity in support of their public policies which they had finally backed up with a concrete achievement.Footnote 2

And yet, to Richard Bonson, a miner, farmer, and entrepreneur, who had helped prepare the picnic grounds on the “top of the hill back of town,” the entire event seemed off the mark, and “a falur [sic] in part.” Though a “great many people” were present, he felt the speeches were too long and the banquet was too rowdy. Most of all, he feared that the social and political tensions among various factions, circles, cliques, and subcultures, roiling just beneath the surface of town society, politics, and culture would threaten the boosters’ efforts and the future of the town itself. After all, only six weeks before, Dennis Mahony of the Dubuque Express and Herald had chastised Dubuque’s divided leaders for failing to plan any celebration for the impending arrival of the railroad cars of the Illinois Central at Dunleith. So too, many grumbled that the Dubuque and Pacific Railroad remained a mere “paper railroad.” Others worried about deepening rifts between Jones and the Langworthy brothers – the “founding fathers” of Dubuque, whose presence was muted, between Jones and the city council about who should pay for the festival, and between Jones and Stephen Douglas who were hardly on speaking terms over a dispute about the politics of the 1850 amendment that had all brought them there. In addition, with limited funds, the event was under-planned and marred by delays, mix ups, and oversights. Finally, the people of the Dubuque and the Illinois Central Railroad were at odds because the railroad refused to adjust its schedules to set arrivals at Dunleith in the early evening.Footnote 3

Many worried that Dubuque’s boosters and citizens were not up to the job of building the Dubuque and Pacific Railroad, and that it would eventually be absorbed into the Illinois Central system. Thus, even as Dubuque residents celebrated this great day in their town’s history, they worried about their future. Did the day mark Dubuque’s arrival as a proud, independent, prosperous future metropolis of the Northwest where middle-class leaders would reap the benefits of their own actions? Or were they bearing witness to their abdication or surrender to powerful regional economic and organizational forces of capitalism that would eventually undermine the local economy and strip them of local autonomy and control, so cherished as a core principal of the booster ethos? Hence the Great Railroad festival seemed to be both a commemoration of their “hometown” and a referendum on its future prospects.

For members of the western middle class, railroad festivals and other booster events in the mid-1850s also marked a new departure in their efforts to expand and increase their social and political influence in Dubuque and American life in general. In the previous two decades since the founding of Dubuque, middle-class residents, like those elsewhere across the urban West, had sought to establish and expand their influence and power over American society, culture, and politics. They did so by achieving a degree of economic success as entrepreneurs, professionals, and capitalists and making western towns like Dubuque their home. Gradually, as they invested more in their hometown, their self-interest and that of the town became one. As a result, by making the local “hometown” “community” the context from which they launched their agenda to play a broader role in American society, their fate and that of the town became one as well.

“Hometown” and “community.” Two powerful words. They remain ubiquitous words that are regularly invoked in public discourse today. Yet with most small towns struggling to survive and most “communities” more “imagined” than real, both have lost much of their impact and meaning. It is hard for us to recreate how powerful an influence the notions of “hometown and “community” had on the formation and development of an American middle class in the mid-nineteenth century. Once described by Robert Wiebe as “way of the town,” the “hometown” ideal imagined a “community” of residents and neighbors who lived in harmony. A “hometown” was, above all, a “face-to-face community” of a small size.Footnote 4 Its residents worked in business and politics to achieve common goals. They were increasingly connected by partnerships and political alliances that often translated into friendship, family relations, and intermarriage. This “hometown” ideal prevailed across towns and cities with an ascendant middle class or bourgeoisie throughout America and Europe in the nineteenth century. From the fictional Buddenbrook family in Lubeck, Germany, to the actual Johann Uphagen family and his descendants in Gdansk, Poland, to the Bovary family of the “country town” of Yonville, France in Madame Bovary, and even to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s portrayal of town life in “Oldtown” in early- nineteenth-century New England, the “hometown” ideal of bourgeois life in small communities in the nineteenth century was shaped by the larger culture and society around it.Footnote 5 In each place, the ideal was a middle class or bourgeoisie ideal. It translated private self-control and discipline into public virtues that gave them power in society, politics, and civic life. It thus provided them with a more personal, secure, and holistic sense of social identity than larger cities provided.

The American version of this ideal emphasized an orderly, interdependent community of free people pursuing their self-interest and providing political leadership acquired through popular male suffrage. The individualist and independent aspect of community life in places like Dubuque, Iowa drew inspiration from the republican social vision of the New England “village ideal” and the so-called republic of little villages that some felt should be spread across America. This was especially true in Midwestern towns like Dubuque, nearby Galena, Davenport, Peoria, Indianapolis, or Chicago. The populations of each of these towns included numerous native-born New Englanders.Footnote 6

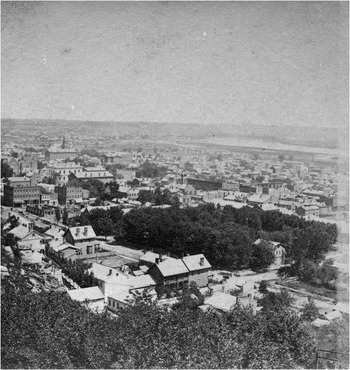

At railroad festivals like that held in Dubuque in July 1855 and countless places across the North in the 1840s through 1860s, local society, the “hometown,” and the “community” that defined it, sat for a collective portrait. In 1867, Samuel Root, a local photographer relocated from New York city, climbed West’s Hill where, twelve years before, the Great Railroad festival had taken place. He captured a set of rare panoramic bird’s-eye photos of Dubuque, Iowa as an ideal American town sitting in the hazy sun (See Figure 1). Though the town had been utterly transformed in the ensuing decade, the images still evoke the “hometown” ideal of a perfect place in the mid-nineteenth century American North. Just beneath the bluffs and to the north, stand clusters of ample middle-class houses. South and east toward the river, lies the business district centered on Main Street where residents had fought a “Civil War in our midst” only a few years before. Amid the higher buildings in the center of the image is the corner of Eighth and Main streets, and nearby, in the trees, Washington Park, symbolic centers of that local “war.” These were the sites of countless meetings, receptions, and celebrations for the Union cause. Further east, along the river in the haze are the river bottoms. There a large immigrant neighborhood of Germans and Irish and a small cluster of African-American residents lived adjacent to the first factories that were appearing after the war as the city adjusted to its new status as a small regional town with a niche economy.

Figure 1. “View of Business District of Dubuque, Iowa,” c. 1867, by Samuel Root, Paul C. Juhl Collection, State Historical Society of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa

The bird’s eye aspect of the photograph, read as a visual document, also suggests a possible theoretical approach that one might take to imagine a total image or “total history” of the life of any town or city. At its core, the image shows an urban place that has been created by the economic, social, political, and cultural actions of people in a particular time and place – the building blocks of all historical thought. Most residents agreed that any town was grounded, first and foremost, by its economic function and development within a regional economy and the system of cities and towns that structured it. In contrast to the old settled towns of New England and the East, that in spite of transformations caused by the industrial and agrarian revolutions, maintained the ideals of a changeless, self-contained community, new western towns were founded amid intense competition, rapidly changing economic patterns, steady in migration, volatile capital flows, and speculation that accelerated the pace and scale of economic change. Settlers and town founders were, therefore, acutely aware that before they could even think of building a community based on stable social and cultural ideals, the town must urgently develop a viable economic function. They also took it as a given that each resident had to find something to do and find a specific role to play in that effort. From the start, therefore, almost everything they did was deeply spatialized because to play a certain role they had to understand how the geographic location of the town affected them.Footnote 7

Early on most settlers imagined that their town would operate within a discursive urban system in which several middle-sized cities, each able to derive its wealth from its surrounding region, operated relatively independently of each other. After the initial competition among numerous town sites and “paper towns” across an area had resulted in one town evolving as a central-place market center, such central-place towns or entrepots would then each have their own relatively independent track or path to develop further within the broader regional economy. In a pre-railroad era, there was enough room for many successful mid-sized towns to thrive, each benefiting from their locational advantages and their distance from each other. Achieving success was – in this view – simply a matter of choosing the right economic function within a given context. One had to apply one’s skills and energy to a viable or appropriate strategy that was in synch with the general growth and development of the city and the region. By this way of thinking, though the imperatives of specialization, division of labor, and economies of scale were hard to avoid, no one should feel aggrieved by how they prevailed. The dynamics of market competition rewarded those best equipped to succeed.

This broader perspective supported the belief that each town economy was, for the most part, built by its townspeople, not some outsiders. They founded it, invested in it, built it, owned it, and developed it further with their own capital, relatively independently from other similar towns. This ideal “hometown” was, therefore, a self-owned, owner operated, self-made place with its own semi-autonomous local economy, complete with its own currency, exchange rates, public budget, interest rates, and balance of trade vis-a-vis other towns and cities. Believing that every town had a chance to develop, they aspired to grow from central places, to urban outposts and onto regional market centers, entrepots, and even metropolises. Throughout local entrepreneurs would invest most of the money, make most of the decisions, develop booster policy, and benefit most from the returns. So long as people and capital kept flowing into their town, and local entrepreneurs expanded their businesses to keep ahead of demand and make sufficient profits to enable them to pay off interest and pay down principal on their debt obligations, locals would control the town’s growth and development. Eventually this would allow them to draw both wealth and population from other towns and cities to their own benefit. In time, many residents of some western towns began to believe that with enough effort they could eventually eclipse the wealth and power of the regional entrepot or eastern cities on their own terms. It is easy, in retrospect, to consider small urban boosters as speculators who took advantage of others by exaggerating the possibilities of their town’s growth. Yet given their understanding – or lack of understanding – of systemic forces – as well as the prevailing contemporary theories of urban growth, it was entirely reasonable for them to believe that their town had a real chance to prevail as a larger city even though St. Louis and Chicago were already establishing significant control over the regional urban system.

In spite of their best efforts to affix an eastern “village ideal” on western towns and cultivate a “hometown” community, they recognized that the market – a source of viability, order, and stability – also separated townspeople by occupations, jobs, wealth, and space. First settlers with capital gained initial advantages in merchandising, manufacturing, and the professions that subsequent arrivals found hard to compete against. Given their advantage, and their connections, they were able to do larger scale business and outcompete smaller, more recently arriving operators. They then invested their accumulated capital in land, real estate, stocks, and went into banking, further enhancing their wealth and affixing their self-interest to that of the town. As a result, they also tended to “persist” longer than other residents, enter politics, and gain a say in running the town. Beneath them, a broader realm of entrepreneurs, small-scale manufacturers, and middling professionals provided local business and services. They also tended to be more mobile. Finally, workers found opportunities working for the entrepreneurs and manufacturers, transport companies, and the town or city itself, but did so in a regional context and were regularly on the move from one town to the next. Each of these strata were further affected by ever changing interactions with the regional economy, as well as by seasonal rhythms and work patterns, that further divided people living in the same town.

Thus economic dynamics, as both glue and solvent, created the foundation of but also worked to undermine the very communal social order that residents strove to create. The market created a social architecture of three distinct strata. But it also created a framework for the emergence of a collective “harmony of interests” that boosters could rely on to promote public policies. Numerous studies employing tax lists and censuses – my own included – provide a dynamic image of society in the urban West. Most hometowns in the West in the 1850s were run by a small, stable core of elite and middle-class residents who stayed in place. They were surrounded by and dealt in everyday life, society, and politics with a broader middle class and common folks, and then workers, whose mobility increased as their wealth declined. Though their respective “material condition” shaped much of their identity, for each group to cohere into a “community,” each had to develop ways to define and secure their social position, interact with others in town, and give meaning to their lives.Footnote 8 They did this by drawing selectively on the prevalent cultural or religious systems in place in America at the time. By the 1840s, among these were individualism, capitalism, professionalism, republicanism, Christianity, civic boosterism, and the male subculture. Through their choices and social experiences, they established and defined class characteristics and boundaries. Then they crossed and blurred those lines in different ways to create a web of social connections and interactions that turned the building blocks of a society into a community.

But, in the end, the quality of social experience in any town lies not so much in the fact that people shared a place, or drew from different cultures to establish themselves and interact across groups and cultures within town society, but rather in how they interacted. What assumptions and attitudes shaped the character and manner of interactions among people within each of these realms? What were their social relationships like? Each cultural system shaped people’s behavior and interactions in different ways. Boosterism, for example, valued participation and cooperation and a fusion of both private and public resources to pursue both personal and collective gain. Thus the expectation that one should subsume individual self-interest to a broader goal seemed at odds with competition driven by self-interest valued in business, or privacy in genteel middle-class life.

On the other hand, gentility was grounded in the hierarchical assumption that members of a group were “the best sort of people” in society. They were “better,” more educated, more refined, and even more “civilized” and believed they lived more meaningful, reflective lives than common folk. Middle-class people employed their sense of noblesse oblige – or social obligation – to soften the tendency of gentility toward exclusivity and snobbishness and the expectation that others would naturally defer to their leadership and emulate their behavior. Evidence that many others actually did pay attention to, look up to, emulate, and even defer to those who lived genteel lives gave that meaning value. It created a “public spectacle,” a collective gaze of townspeople – especially at public events like railroad festivals – that helped weave society together.Footnote 9

Middle-class people living in a small face-to-face community also recognized that they had to earn others’ recognition, cooperation, and support by interacting with a broader segment of town society through politics and the male subculture. In politics, politicians accepted the fact that party leaders expected them to be loyal and obedient for the sake of party unity and success. In return, they might be rewarded by the party’s patronage system. And if not, as in business and the professions, they had to handle disappointments when the assumed “quid pro quo” arithmetic of expectation – job for participation, loyalty, and work – did not pan out. Here, as in the male subculture, they had to learn to “take it” and remain resolute and loyal and try again later. Whether loyal or not to the party, all politicians and public officials recognized that in a democracy they were beholden to the vote of the people, and thus had to regularly – like any “county politician” – interact, fraternize, and socialize with the people.

To aid in this “education” among men, Main Street merchants, boosters, and professionals indulged in a number of behaviors associated with the male subculture, ranging from sarcastic verbal jousting, collective socializing and drinking, to frolics – an intriguing practice in which groups of men ran or paraded around town acting like children on a playground. Whether they forged true friendships, helped one dissemble and disguise one’s true emotions, or defused underlying tensions, each of these practices helped men emotionally manage both success and failure while competing intensely among one’s “brothers.” They also helped maintain reasonable behavior in often highly volatile social situations. As such, group and class identities were fluid, dynamic, and changing, even as people sought to make them static and changeless.

While concrete social structures existed in people’s everyday social experience, they are, as Pierre Bourdieu has suggested, distinctions constructed of choices that are mere “abstract representations” and fictive constructions. They were created or produced both by the people within them behaving in certain ways, as well as by social others observing and analyzing them from outside in the course of their “social experiences” over time. “Social experience” is rooted in the ways one acts and behaves as a social being. Relationships with family, friends, and others at work and in the public realm of strangers form the structures in which we position ourselves in society and thus define ourselves socially. Most of this “social work” is reflected in the ways we maintain ourselves physically, present or identify ourselves to ourselves and others, and behave toward or with, and interact with others in informal and formal groups and organizations on a day-to-day level. Much of this activity flows from one’s economic and thus material basis and thus occurs in the realm of material things among which one lives one’s everyday life in a particular place. One way to present and imagine these frameworks is to make them “material” and “spatial” and recognize that all social interactions, like daily life itself, occur in space. From this perspective, social interactions become “spatial” interactions. Going beyond Harvey, one could argue that “social relations” are not only “mediated by material things” or embodied in “materials things” but also are imprinted on space and place.Footnote 10

Thus social groups inevitably create and shape “social spaces” – whether public – for others to see – or private – out of public view. As one lives in a place and acts according to the modes of behavior acceptable within that space, one claims a social space for one’s group. One gradually invests that place and space with meaning by telling stories about it as a place or space where the stories of one’s life have unfolded. By telling stories and recalling memoires of previous experiences at certain places, one imprints one’s personal, group, or social “spatial narratives” on them. The physical town, its streets and buildings, becomes, over time, a reflection of who one is and what one intends. In this way, one imbues a town with meaning as one’s “hometown.” It becomes, in time, if one makes the effort or cares to do so, a deeply felt reservoir of meaning replete with memories and even “thought figures.”

For many, one’s town became a nostalgic, indeed almost mythic place. It invariably became the “old town” or “old Galena,” in “old Jo Daviess” county or “old Davenport” or even “the good old town.” It was forever one’s “hometown” centered on “Main Street.” Abraham Lincoln expressed this in his sad farewell address from Springfield, Illinois in February, 1861. “To this place and the kindness of this people I owe everything.” It was the place in which he had “lived a quarter of a century” and “passed from a young to an old man.” It was a place where his “children have been born and one is buried.” It was a place, if one left, one would always carry within one as part of one’s identity. It was the place in which one claimed one’s social space, contested other spaces, and politicized still others. It was a place where one created a “meaningful narrative” that gave shape to one’s future personal and social agenda, and life.Footnote 11

Ironically, middle-class efforts to consolidate their position and identity within an increasingly complex urban structure, also presented its own internal challenges. The gradual differentiation and segregation of various groups into different social realms, eventually enabled people to live more routine, isolated, and, thus, less interesting lives. This was the intended result. Routine allowed them to go about the business of living predictable lives. Predictability allowed them to focus on pursuing their core social agenda of reproducing and expanding their class ideals, values, and behaviors and thus influence and power. For some, this self-segregation from a broader life cultivated a richer private life. It encouraged more introspection, emotion, self-discovery, and thus fulfillment. Diaries of the time often attest to this. But, for many less introspective people who found the “unexamined life eminently worth living,” the social “spatial narratives” of middle-class people became a litany of repetitive daily routines. Routine hardly merited comment and the daily “passage of time” became almost timeless, “transformed into … more secure structures made of objects, acts, words” dissolving “almost invisibly into the historical record.”Footnote 12

Letters full of phrases such as “no news” or “nothing particular” reflect the lack of stimulation and even boredom. Dreaminess and somnambulism penetrated middle-class life. In the Civil War years, some began to believe that they had “been asleep for forty years al la Rip Van Winkle.” This was fertile ground for the smugness, lack of curiosity, banality, philistinism, and conservative resistance to any change often associated with middle-class life. On the other hand, it could also be taken as an indication of their awareness of and growing frustration with daily routine. More and more middle-class people around mid-century expressed the desire to be “wide awake” to the realities of their times. The Wide Awake clubs of the Republican Party that supported Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 campaign, for example, urged their followers to “wake up” to the sectional crisis. Others, more generally, as the sectional crisis deepened, finally felt that they were “wide awake” and living in “wide awake times.” Civil War letters are suddenly full of details about social actions within new social spaces or situations, reflecting both the disorientation and the excitement that comes with encountering new people, places, and experiences – literally bumping up against the “hard surfaces of life.” Either way, it broke them out of the routines they had created for themselves.Footnote 13

While the separation of home from work, private from public, interior from exterior, and middle class from workers helped people construct more meaningful social identities, it also fragmented their social interactions within the larger community. The transparency and organic wholeness of traditional face-to-face or “folk” community life eroded. People, even in smaller towns, increasingly separated and insulated themselves from each other. Over time they knew less about each other. “Primary” social interactions were replaced by “secondary” ones. Middle-class people, especially, drew a veil of secrecy over their private lives. As people retreated within their own social spaces, society became increasingly obfuscated by appearances and “spectacle.” Social knowledge and deep friendships were gradually replaced by impressions and acquaintances. “Plain talk” and direct and real communication was supplanted by public discourse. Gossip, hearsay, public speech, ideological rhetoric, and cant replaced personal communication. Social interactions and communication became less real and authentic. They seemed increasingly staged or performed. Hence one’s understanding of social “others” declined and one’s own sense of identity and satisfaction within the broader public realm of community and society eroded.

This was especially evident after the financial panic of 1857 and during the recession and war years that followed. Throughout the period one can discern the rumblings of what would become a core middle-class anxiety in the “modern” urban world. As their meaningful connections with others in the “public” diminished, and “society” and social life in the city became less and less knowable, many middle-class people expressed frustration, disappointment, anxiety, and even, alienation. In response, the middle class engaged in much soul searching about their personal and social goals. Peter Gay suggests this could go both ways, both negative, as well as positive, the latter involving personal freedom. That some of these unexpected consequences of their efforts to establish hegemony in American society became apparent in the rapidly changing 1850s and 1860s is one of the central themes of the story that follows.Footnote 14

But such interior concerns of the middle class lie beneath the public surface of the built environment and how different groups in town created various “social spaces” that made up any town’s social footprint on the ground. Collectively, these spaces, shown in the image, reflected the social structures of the town, the shape and dynamics of the “community” of local society, and the history of the hometown and larger society of which it was part. Such a “hometown,” like so many across the West and North would be the point of departure and source of strength and resilience – to which many would remain emotionally and socially tethered – as they sought to respond, as best they could, to the dramatic regional and national forces and challenges of economic boom and bust, crisis and recession, and Civil War in the decade to come.

Lower Main Street and “Uptown”: The Mercantile Elite

The social footprint of Dubuque, Iowa, one of the most vital frontier small cities in the Great West that drew national focus and attention, emerged from the intersection of geology, landscape, and the logic of the market place within the larger regional economy. The presence of lead, a much needed mineral in various industries, within its surrounding bluffs, hills, and valleys put the town, literally, on the map in the 1830s. By the late 1830s, Dubuque was a small mining outpost and satellite of St. Louis, secondary to nearby Galena, the main entrepot of the so called Lead Region that stretched from northeastern Iowa across northwestern Illinois and into southwestern Wisconsin. By the 1840s, a rush of settlement into the back country as well as further upriver toward Minnesota added a strong local mercantile sector with connections to St. Louis and the east to the economy. Gradually Dubuque’s merchants, with the help of new steamboat connections north and south, chipped away at Galena’s dominance in both directions. When, in the mid-fifties, Dubuque entrepreneurs started their own steamboat company and the Illinois Central arrived in Dunleith across the river, Galena’s fate was sealed. Processing and small-scale manufacturing, as well as banking, brokerage, and land sales, increasingly funded via Chicago and New York, quickly emerged in the early and mid-1850s. As land values rose, immigration increased, and the economy boomed, Dubuque stood suddenly poised – before the real appearance of St. Paul as a competitor – to become the entrepot of the northwest.

Within this general framework of economic development, a small group of entrepreneurs who arrived early and gained the lion’s share of the mining business became wealthy and emerged as the town’s elite. But as the city’s population grew and local trade increased, a small mercantile and professional elite began to develop. In time, supported by the shifting of the main source of town wealth from mining to merchandising, banking, real estate, and manufacturing, the middle class grew larger. Those who arrived earlier rather than later, tended to have more capital. As a result they achieved greater efficiencies and thus gained a competitive advantage over their rivals. They then built upon that initial advantage to gain greater returns on their labor and investments. As a result, the wealthy got wealthier, while others progressed more modestly, and many, indeed perhaps the majority, merely broken even. In addition, those who achieved success tended to stay longer in town, while those who did not moved from one town to another, creating a divide between the early settler elite and the highly mobile “movers.”

Hence, in Dubuque, as in most western towns, the dynamics of the market place translated into a differentiated social structure. Those who prevailed in the competition among early settlers usually emerged as the town elite. Beneath them, a broad, dynamic, and loosely defined middle class whose members sought to control mainstream society and town politics gradually emerged. Rarely more than a fourth or, at most, a third of any town’s population, middle-class folks from Main Street were compelled to confront and interact with a growing working class as more and more workers were drawn to the city for jobs in the small manufacturing, construction, and transportation services. Over time, these structures became more pronounced, heightening social and political tensions and undermining efforts to develop or maintain any framework of common interest among citizens.

The spatial arrangement of the city by the 1850s reflected both Dubuque’s trajectory of economic development and its shifting position within the regional and the general pattern of its social development. Extending northwest from an inlet of the river to the south, the wharf was established where this inner harbor’s deep water came closest to the river channel. The city plat was squeezed or “compacted” onto a narrow plain or “terrace” and that stretched from southeast to northwest from the wharf between the meandering river with its numerous backwaters and inlets on the east and the two-hundred-foot-high bluffs less than a mile to the west. At the wharf – the town’s economic nodal point – the local economy intersected with the regional economy and shipping system. Several blocks to the northwest on lower Main Street, merchants and bankers sustained the local economy. The concentration of warehouses, stores, and banks on lower Iowa and Main Streets respectively – located there for access to both the river trade and town and hinterland residents – made it the center of exchange and investment in the local economy. Manufacturers who began producing goods for local and regional consumption – and thus generated development through import substitution – in the late 1840s needed more space than was available on crowded Iowa Street, the wharf, or lower Main Street, and pushed east and northeast along the river. Residents who found the hustle and bustle of Main Street – as businesses crowded out boarding houses and residents as it moved north in the 1850s - harder to bear, moved, according to their income and needs, into adjacent residential neighborhoods to the east, north, and west of downtown. Middle-class people moved near the base of the bluffs and extending to the north, working class to the east and northeast of Main Street with Germans to the north, Irish to the south in “Dublin,” and a small black population scattered in between. On south Locust Street, below Second Street leading to Dublin, there were only “One & Two Story Frame Buildings and … Hovels and Shanties” and “Doggeries & Low Class Boarding Houses” occupied by both Irish and blacks that gave the area such a rough reputation that, “Decent People hardly dared go down that St[reet].” By the 1850s, several members of the elite distanced themselves further from town by building larger houses up the hill toward the bluffs, on top of the bluffs, or – in southern style – on suburban or “borderlands” country farms or estates from two to five miles beyond the outskirts of town, west and north across the adjacent countryside.Footnote 15

In 1834, a group of settlers who had settled at scattered lead-mine sites across the nearby hills and bluffs, met at the wharf to found, and plat, and begin to improve the streets of Dubuque. Chief among them were James, Edward, Lucius, and Solon Langworthy who had discovered rich deposits of lead in Langworthy Hollow north of town. In need of an outlet for the lead they intended to smelt, they establish a wharf, and then platted streets diagonally heading north and from the wharf, where the two streets that intersected with the wharf were named Iowa and First Streets. A block to the east at Main Street and First, engineers platted the beginning to the Military Road – contracted by Lucius Langworthy – that would run southwest into Iowa territory to Iowa City and west to Fort Des Moines. Two years later, the Langworthy brothers formed a partnership and opened a land agency, mercantile emporium, and bank down at the northeast corner of Main and Third Streets. In the mid-1840s they replaced a wooden building with an impressive brick block that quickly became the economic center of Dubuque. The Langworthys also owned and operated a hardware store on Main Street above Fourth, as well as a commercial structure across the street in which they rented commercial space and offices out to others. In the later forties, their brother, Solon added to the Langworthy presence downtown by building an impressive jobbing house at First Street on the wharf.

By the mid-1850s, lower Main Street between Second and Sixth Street, anchored by the Langworthys Bank, agency, and merchandising house, had emerged as the center of Dubuque’s public life of work, business, policy, and politics. It was “from the earliest days the Main business part [of town] up to 1855.” To the south, above the “mud holes and frog ponds,” “saloons and hash houses,” taverns, and “cheap” boarding houses of lower Main Street, the impressive Julien House Hotel, at Second and Main, described as “The Pride of Dubuque,” marked the entrance into “uptown” as Main Street gradually inclined up past Sixth Street. Next door was the Telegraph and Express office, Dubuque’s connection, aside from the Post Office further up Main Street, to the outside world. Its location would attract several newspaper offices to locate on lower Main Street through the years. The Dubuque and Pacific Railroad had an office on lower Main at 56 Main Street. In the building boom of the mid- fifties, old wooden structures that remained were replaced by a series of four to five storey brick blocks that created a solid built up wall along both sides of Main Street. So too, Main Street was covered with macadam and gutters were built and all the old awnings and sheds along the street were demolished, presenting a modern urban look that one local observer noted “Dubuquers may well be proud of the Main Street of their growing city.”Footnote 16

In their stores and offices on Main Street, each of Dubuque’s prominent merchants, bankers, lawyers, businessmen, and manufacturers, pursuing their economic self-interest, had his own career story of beginnings, successes, setbacks, and ultimate achievements that helped write the economic history of the town. James, Edward, and Lucius Langworthy, for example, ran a veritable economic empire from their bank, land office, and merchandising houses on Main Street. They were considered by most the “founding fathers” of Dubuque. After arriving between 1829 and 1832, they struck a number of “rich leads” in the Couler Valley northwest of Dubuque, which was dubbed “Langworthy Hollow,” built a smelting furnace in Langworthy Hollow, and established the foundation of their fortune. When the mining business went into a decline in the 1840s because of falling prices, the Langworthys diversified into merchandising, land sales, and banking. By the mid-1850s the Langworthys “owned the most valuable lands in and about the city,” only banked in specie and limited their liabilities, thus making them rarely “obliged much to anybody.” Owning the richest firm in town, the Langworthys, individually, were also the richest men in town, each worth several millions of dollars in today’s terms, paying together about one-twelfth of the town’s taxes.Footnote 17

Around the corner on Fourth Street, in a small brick building less than a block from the Langworthy’s bank in an otherwise dingy block with a tavern and drug store, Richard Bonson, one of the Langworthys’ chief competitors in the mining business, established a small business office. He spent most days there over the years doing business and playing a role in public affairs, railroads, and politics more conveniently than he could from his house out in the country several miles west. The nearby courthouse, the Dubuque and Pacific Railroad office, and nearby hotels were part of his daily rounds. Bonson’s personal and business story paralleled that of the Langworthys. An immigrant with a large group of settlers from Yorskshire, Bonson had followed the Langworthys to Dubuque in 1834. Aware that the Langworthys had already owned most of the mining lots up the Couler Valley, Bonson joined the contingent of later settlers who took their search for lead to the south of town, near an old Indian village adjacent to Julien Dubuque’s mines at the mouth of Catfish Creek. Within a few years, Bonson had claimed a number of plots along the north face of the Catfish Creek valley and established two smelting furnaces near Catfish Creek that formed the structure of his economic life.

Though Bonson aspired to self-sufficiency, his world, like that of other miners and farmers in the West, was driven by the underlying logic of the market place. Bonson, unlike smaller producers, was able to endure the shakeout, muddle through a low-price market for lead in the mid-1840s, and then, after the federal government slapped a prohibitive tariff against English lead, take advantage of rising prices and demand by generating record production after 1845. So too, after a few record years depleted all the easy and rich leads, and costs increased and profits margin evaporated, Bonson was among the larger miners like the Langworthys who could continue to buy, work, and sell mineral lots and mineral. Many could not and turned, instead, to building furnaces and purchasing “mineral” from the big miners to smelt into seventy pound “pigs” of lead that they sold to wholesale shippers in Galena, or, after 1850, increasingly to lead companies in St. Louis. Eventually, as all the accessible lead had been mined, not even rising prices in the 1850s, such as those in 1853 in Galena, when “scarce a man in town was idle; merchants, lawyers, mechanics, and day laborers with pick and axe and spade” were “prospecting almost everywhere,” the industry slipped into a permanent decline. Even Richard Bonson, after a few break even years in the 1850s, recognized that the central dynamic of his economic life was eroding, and facing “dull prospects for the future,” concluded that though he was “worth plenty of money,” he “must be doing something” else.Footnote 18 Though Bonson was a believer in tangible, homegrown wealth which he treated like a “loose cloak” and viewed venture capital that one invested in revenue-generating activities as an alien capitalist idea, he, like most others, would turn toward booster efforts that sought to advance the continued growth and development of his “beloved city of the mines” as a way to move forward.

Most other businessmen on Main Street followed the trajectories of the Langworthys and Richard Bonson’s careers. Again and again one finds businessmen’s careers following the same rise of the 1840s, then a settling off, followed, depending on their work, by a broader boom in the 1850s during which they became more involved in capital investment, real estate, and the railroads. Horatio W. Sanford, a lawyer turned capitalist began buying and trading small parcels of land near the city and in 1850 opened his own land agency in a second floor office of a building below Fourth Street on Main. With his success he moved a few years later to a front office on Fourth and Main, “then the center of business” in town, and then, in 1856, into his own “Sanford Block” further north up the hill. In 1858, with a fortune of $100,000, he purchased the Rebman Block at Eighth and Main Streets in Dubuque and moved his land office into that opulent structure. So too, Major Mordecai Mobley operated one of the wealthiest banks in Dubuque, having established it in 1844 after emigrating from central Illinois, and by the mid-fifties he was one of the most trusted and wealthiest businessmen in town.Footnote 19 Thus collectively, while economic forces divided and differentiated townsmen, they also brought them together and created a new capitalist class on lower Main Street.

Upper Main Street: The Bench and Bar and “Fraternal Democracy”

At the top of the hill beyond Main and Sixth Street, business houses began to give way to more service and public-oriented venues. Early on, the buildings on upper Main Street – at the crest of the hill rising up from lower Main Street – encroached on some interspersed residences, gardens, and open lots that had been established earlier when Sixth Street was way out of town. In the building boom of the 1850s, however, a steady wall of business blocks and structures filled in Main Street up beyond Ninth Street. Most of Dubuque’s lawyers, politicians, and newspapermen had their offices on Main Street above Fifth Street. During the years 1853 through 1857, scores of buildings were built above Sixth Street, filling in what vacant lots or shanties that remained. This expansion of Main Street north was driven by a shortage of space further down Main Street, a desire by some to distance themselves from the wharf and the “element’ that prevailed in lower Main Street area, as well as a desire, or a need, to locate near City Hall over on Iowa Street and the old courthouse over at Seventh and Center Streets. To the east, the courthouse was one of the central meeting places in town. The fact that the Post Office was located in the Globe Building at Fifth and Main reinforced the centrality of this section of Main Street for professionals. To the west, at Locust and Sixth was a small square, hence giving to Sixth Street off Main near the Post Office the name of “public square.” Predictably, this cluster of the public buildings attracted the theaters, clubs, and lodges that served as the venues of Dubuque’s entertainment and associational life. By the mid-1850s, the Odd Fellows Block (on the south east corner), the Masonic Hall, and The People’s Theater, all clustered around Eighth and Bluff Streets two blocks west of Main. Their proximity transformed Eighth Street and Main Streets into a key “public” place – indeed it became one of the central meeting places – in the public discourse of the city.

The members of the bench and bar located their offices, as they did in almost every town and city, around the Post Office, the Courthouse, and newspaper offices. As noted, Dubuque’s Post Office operated out of the Globe Block at Fifth and Main during the 1850s. The impressive structure was built in the building boom of 1849 by David S. Wilson and Platt Smith. Both of the Wilson brothers and several other lawyers had offices upstairs in the Globe Block. George Nightengale and Phineas Crawford were their neighbors. Dennis Mahony and Joseph B. Dorr printed the Democratic newspaper The Dubuque Express and Herald from their third floor office. Because they apparently posted the latest edition at street level, the street in front of Globe Block became a regular gathering place among residents. In the 1850s, most days Mahony could be found there or at his real estate office over at Seventh and Main streets. William J. Barney, a noted lawyer, land broker, and, since 1853, capitalist/banker associated with Cook and Sargent of Davenport, had his office on Main above Fifth Street. After 1857 he would move down to 125 Main Street.

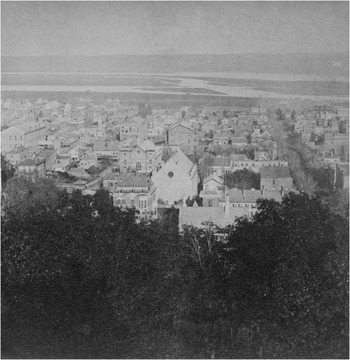

Just to the south, George Wallace Jones, and William Vandever, Democratic U. S. Senator from 1848 through 1859 and lawyer and then Republican U. S. Congressman from 1858 until he mustered into the Union Army in 1861, respectively, kept rooms for local business in Shine’s Block on Main between Fourth and Fifth, making it Dubuque’s conduit to federal power. When they were in town, their presence transformed the block into a political center of town – especially for Democratic Party politics. Lincoln Clark and his partner Frederick Bissell had an office at Main and Sixth, while Ben Samuels and Platt Smith moved up to the Law Block at Seventh and Main by 1857. Attorneys also rented offices in Rebman’s block, later named Sanford’s Block, on the corner of Eighth Street. Samuel Root, a well-known photographer from New York city opened a “Daguerreian Gallery” there in October 1857. It also later had an armory into which the Governor’s Greys, an early militia group, moved in 1859. H. W. Sanford’s Tremont House Hotel was located on Eighth Street west of Main Street (See Figure 2).Footnote 20

Figure 2. Main Street Dubuque, Uptown Area c. 1867 by Samuel Root. Most of these buildings were built in the boom of the mid-1850s. Samuel Root, Paul C. Juhl Collection, State Historical Society of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa

Not surprisingly, the career trajectories of most of the members of this professional elite who controlled law and politics paralleled those of the business elite and the town economy in general. As in every other frontier town, lawyers arrived with the first miners, entrepreneurs and settlers and played a central role in the efforts of those willing to promote and develop the town in establishing civil authority, public policy, and social order. Contested miners’ claims on federal land, disputes over land titles held over from before the general settlement of the area by whites, along with the establishment of a territorial district court in 1836 and the U. S. Land Office in 1838, made Dubuque a promising location to settle for frontier lawyers in search of opportunity. Even so, those who arrived first tended to grab a lion’s share of the local business, or stood favorably poised to go into the world of politics.

George Wallace Jones, a native of Indiana and formerly from Missouri, and territorial judge in Wisconsin, had arrived in Dubuque in 1835. Stephen Hempstead, a cousin of Charles Hempstead of Galena, arrived in Dubuque in 1836 and, with William Coriell, who arrived a month before, was “the first lawyer who commenced the practice of his profession” in Dubuque before being elected to the territorial legislature in 1838. Warner Lewis, a fellow Missourian and friend of Jones, joined Hempstead the same year and, after a stint as clerk of the district court, and then as Justice of the Peace, joined Hempstead in the territorial legislature in 1838. Thomas S. Wilson arrived in Dubuque later the same year, joining Hempstead, Peter Engle, and William Chapman (a “visiting” lawyer from Burlington who settled in Dubuque for a while) as one of only four practicing lawyers in town. Wilson was soon appointed county prosecuting attorney and tried his first case before Justice of the Peace Warner Lewis. Wilson, after serving as town trustee and carrying on an extensive practice in Dubuque and southwestern Wisconsin, was in June 1838, “without solicitation on his part” appointed Judge in the territorial Supreme Court, a position he held until 1847, a year after statehood.Footnote 21

As in most towns, these “fathers of the bar,” members of the “old guard,” were able to grab most of the town’s litigation. They quickly became the town’s legal elite, even as they actively competed for cases and business. This highly competitive dynamic quickly translated into political factions and divisions in the effort to gain public appointed or elective offices. Thomas S. Wilson, “was engaged in almost every suit” in the local courts over at the courthouse, making it difficult for other new arrivals to break in without his cooperation or support. Even Lincoln Clark, an experienced lawyer upon arriving in Iowa, recognized that certain lawyers got all the cases because “they are old lawyers and well known; the great and almost insuperable difficulty for a stranger is to make the first step.” As elsewhere, Wilson and the other “old lawyers” protected their practices by avoiding direct competition and controlling membership in the local bar. They also formed an informal bar association that met at various venues on Main Street or in the courthouse and screened entrance to the bar by administering “bar exams,” expecting new arrivals to have letters of introduction from a sponsoring lawyer down river, or inviting individuals to join a partnership.

Thomas Rogers, for example, a New York lawyer who arrived in Burlington in 1835, was immediately accepted into Dubuque’s legal community and started a practice on the strength of the “prestige of success” from a letter of recommendation from U. S. territorial delegate Augustus C. Dodge (of Burlington) to fellow delegate George Wallace Jones. In contrast, in March 1842, Platt Smith, after reading law by himself “during the winter,” simply arrived “in old clothes … and knowing “no one in the town,” was initially rebuffed in Dubuque, but after gaining entrance into the local bar at Muscatine, returned “to practice where examination had been refused him.” In contrast, Lincoln Clark, a Massachusetts-born lawyer from Tuscaloosa, Alabama, only came to Dubuque in 1847 after a two-year decision-making process and with assurances from George Wallace Jones that local Democrats would not hold his recent southern residence and his reluctant slaveholding against him. Thus when another local lawyer who had “obtained decidedly the leading business here” within only “the space of eighteen months,” passed away, Clark chose Dubuque over Chicago, because he felt he could advance more quickly there. Footnote 22

As newcomers arrived and were admitted, local lawyers established a myriad of partnerships to broaden the range of cases they could cover, allow them to ride the circuit, and manage their legal practice if, as was often the case, one of the partners was elected or appointed to public office. Most of the lawyers noted were partners at one time or another, as partnerships were formed and disbanded as opportunities or circumstances affected business. As business increased throughout the 1850s, the establishment and rearrangement of partnerships became increasingly routine and frequent. Through such arrangements, local lawyers got to know each other, divvied up the lion’s share of the circuit and Supreme Court cases and emerged as a local bar elite who, by way of being appointed or elected to public offices, quickly exerted power in politics and the booster ethos.

By establishing a network of professional, social, and personal relations, the members of the bar pooled their skill, knowledge, and mutual support to provide Dubuque and northern Iowa with its political leadership and ideas for a generation to come. Lawyers were routinely first to be appointed or elected to territorial offices. Once they were in place, friends and associates in the bar sought appointments to offices and gained the support of incumbents when they tried to run for elective office. Thus the geography of circles, cliques, and factions within Dubuque’s dominant Democratic Party emerged naturally out of the structure and dynamics of the local bar. When, for example, George Wallace Jones was appointed territorial judge in1833, he acquired the political connections and visibility that enabled him to be elected territorial representative in the U. S. Congress in 1835. When, in 1842, Jones used his connections and influence to keep the General Land Office in Dubuque, he acquired almost a proprietary power over the office and was appointed Surveyor General in 1845, from which he acquired the “title” “General” Jones. In 1848, Jones ran for and was elected U. S. Senator by a single vote in the state legislature over fellow member of the Dubuque bar and former Iowa Supreme Court justice, Thomas S. Wilson. Out of this acrimonious campaign emerged the core factional division that dominated Dubuque’s political life. Indeed, Wilson’s two more subsequent losses to Jones or to one of his protégés in 1846 through 1852 “engendered a long political” … “between the two townsmen,” that created two factions – the Jones men versus the “bolters” – who were as fiercely opposed to each other as the “Montagues and Caputlets.”

Local politics was soon divided into two distinct groups – those who were loyal to Jones, and those who, for whatever reason, were not. Among the first group were lawyers William Barney, Caleb Booth, Warner Lewis, and, to a lesser extent, Thomas Rogers, Lincoln Clark, and Richard Bonson. Jones’s power, and his ability to control his faction was grounded in his control of the patronage for territorial offices. According to the quid pro quo basis of personal and political power within the patronage system that formed the foundation of “fraternal democracy” and dictated who would be appointed to government offices, Jones would only appoint “friends” who loyally supported him. In contrast to the ideals of responsibility and reciprocity that guided some professional and political relationships, local politics remained rooted in the traditional belief that obedience and deference were the building blocks of power. If given, the receiver then felt some obligation, indeed a sense of duty, to reciprocate and do something to benefit his “loyal” followers.

An adherent of this traditional gentlemanly code of equal among equals, Jones dealt fairly and reciprocally with others and “was a loyal friend.” But his friendship was founded on the dictates of the southern code of honor. He guarded his reputation scrupulously. He expected others to accept his power unconditionally. He demanded loyalty, not candor, openness, or fairness from his political “friends” and subordinates. Such friends became known as “Jones men,” or, as his opponents charged, his “tools” or “sycophants,” a number of whom went so far as to do Jones “the honor” of naming a son after him. A “Jones man” surrendered his political and social independence – some would say his soul – and became what some called “Jones’s ‘tool’” for the sake of personal loyalty. In return, Jones aggressively used his “influence” and worked for the “interests of his friends whenever a fit opportunity occurs.” But if one crossed him, or were less than loyal, or suspected of joining any “cabal, clique, or set,” to “injure Jones,” he would act ruthlessly to end one’s political career. This was a recipe for both intense bonds of loyalty and bitter enemies.Footnote 23

In a town like Dubuque, the political career of almost every Democrat one met on Main Street was determined by their relationship with Jones. Indirectly, as a result, Jones’s “influence” eventually filtered into most public booster and civic projects in town. It also shaped many private lives. Among those whose careers were fashioned by Jones were Thomas Rogers, William J. Barney, Warner Lewis, and Caleb Booth. Likewise, the career of Lincoln Clark was almost singlehandedly managed by Jones. Jones sponsored Clark’s arrival in Dubuque, gave him entrée into the Jones faction, and in 1848, got Clark elected U. S. Congressman from the Dubuque District, after being a resident for less than three years. But when Clark arrived in Washington D. C., and learned that the calculus of power “behind the curtain” required him to serve as nothing more than a sycophantic “Jones man,” he would recoil and turn against Jones’ presumption and arrogance – declaring himself sick of his “demagoguism [sic]” and concluding that “he has no power to sustain himself in any other way.” After all, Clark had always shown a problematic independent streak by tending to associate too freely with both Whigs and other Democrats in opposition to Jones – the Wilsons, Ben Samuels, and others. Disgusted with all Washington politics, as a “fleeting show” of “wickedness,” arrogance, pretension, and “fashionable dissipation,” and unable to combat the “inimical conspiracies” against him, Clark found himself placed under the “ban of oligarchy” and knew he was “finished” “politically.” When he was defeated for reelection he returned to Dubuque. He felt humiliated and mortified but was determined to give his career one last chance. At home, he tried twice to run for state office as an independent Democrat, but was defeated both times. With his political career over, he retreated to his law practice and only gradually reentered town politics and booster activities as an independent.Footnote 24

Richard Bonson’s career followed a similar trajectory. In the early 1850s, when he gained Jones’ support he was elected to the state legislature and surprised to find himself suddenly referred to as a “Jones man.” Bonson’s entrée into the Jones faction was marked by gifts from Jones, invitations to special suppers, and being involved in Jones’ visits to Dubuque. In a visit in 1853, Bonson played his role as a kind of advisor by spending time at Jones’ impressive house, giving Jones a tour of the lower town in regard to Jones’ railroad interests, and even a tour of the bluffs to look at real estate. Yet, after Jones’ reelection, Bonson and others steered a more independent course. Upon his return to Iowa City in January 1853, he continued to associate mostly with “Jones men,” but he also broadened his circle to include those who were not “Jones men.” As a result, Jones quickly withdrew his support, and though Bonson managed to survive for another term, he could see which way the winds of political change were blowing. Like Clark, he learned that with Jones it was total loyality or exile from the Democratic Party.Footnote 25

Meanwhile, facing what now seemed like the impending end of his career in the U. S. Senate – which did ultimately happen on 15 January 1858 when the Iowa State Legislature elected James Grimes, a Republican, as Iowa’s U. S. Senator beginning on 4 March 1859 – Jones could have, like a number of Illinois prominent Democratic Party politicians had in the early 1850s (See Chapter 4), leave Dubuque for the more securely Democratic west coast to revive his career. Jones, however, was too deeply attached to Dubuque and his belief in the “hometown” ethos. Thus, like many politicians, he joined local businessmen and lawyers in the boom of 1855 and 1856 as a town booster who plunged further into commitments as the euphoria of the boom swept caution aside in pursuit of making it the future great emporium of the Northwest. In doing so, he moved politically toward positions on public improvements and the federal funding of railroads that seemed more like those of his Whig and then Republican opponents.

In 1849, Jones tirelessly worked to acquire federal appropriations for a north to south railroad across Iowa, the Dubuque and Keokuk Railroad. Later he got Stephen A. Douglas to amend the Illinois Central Act, to designate Dubuque, rather than Galena, Illinois as the terminus of the road. With this stunning legislative achievement “Jones’ stock” advanced yet again, vanquishing his enemies, while touching off a “war” between Galena and Dubuque that ultimately, ended in favor of the latter. So too, when again in the mid-fifties, Jones gained a narrow reelection, he worked tirelessly for federal appropriation of land grants across Iowa for the construction of transcontinental railroads. After two failures in the House, primarily because he continued to support a doomed north to south route that to non-Iowans seemed insufficiently “national” to warrant a federal grant, he pushed through legislation in the Senate on 9 May 1856 that designated four corridors of public land to be granted to railroads across Iowa emanating from termini at Burlington, Davenport, Lyons, and, of course, Dubuque, sealing the town’s triumph of the year before. Even so, his efforts had less and less political impact as the Republicans swept into power across the state, if not locally in Dubuque.Footnote 26

Collectively, these emerging parallel, and at times overlapping, structures in business, the bench and bar, and politics, created the architecture of local society that shaped social relations and the social geography of hometown life. Yet, in spite of their best efforts in the mid-1850s to cooperate in booster policies, these imbedded divisions and structures would remain visible and shape all their subsequent efforts to respond to panic and hard times, and go to war.

Cultivating Gentility

Such oligarchical control of the local politics and professional life through patronage and managing the matrix of “friendships” was reinforced by middle-class and elite residents’ use of gentility to claim social prestige and thus social leadership. By living a genteel lifestyle – both materially and behaviorally – one presented oneself as a “refined” person whom others could emulate. To broaden the reach of gentility, genteel people sought each other out and established both private and public venues, institutions, and “social spaces.” Genteel people separated their private lives from society by building genteel houses on the edge of or, where there were hills or bluffs, above town. Free-standing houses provided a private space in which to cultivate the private family agendas of the middle class. Their parlors and dining rooms replaced halls and hotels as the predominant venues in which one engaged in more formal “genteel society.” They became the sites of an endless round of calling, visits, tea parties, parties, club meetings, and dinner parties that shaped middle-class life. Publically, this involved establishing genteel beachheads on Main Street and across town.

On Main Street in Dubuque, the Julien Hotel and the Julien Theater inside it, and the Globe Hotel and its Globe Hall and theater, outside of which the first gas light illuminated the darkness of Main Street at night in the mid-1850s, provided the central venues for the early public display of gentility. Balls, cotillions, and theatrical performances, put gentility and refinement on display amid the still rather muddy, rough, rowdy, and dingy Main Street environment. So too, the Congregational, Episcopalian, and Catholic churches, located along the base of the bluffs a few blocks west of Main Street, provided halls and meetings room for genteel associations to meet. Eventually, some associations such as the Odd Fellows would construct their own club houses uptown just off Main Street on Eighth and Ninth streets. Otherwise, there were a few clusters of dry goods stores, groceries, and milliners from Second to Ninth on Main Street, interspersed with business and venues, including offices, saloons, hotel lobbies, and taverns, where both genteel and more common men worked and recreated in a mixed social environment. There was, however, no real shopping district where women would feel comfortable and at ease. Dubuque, like most towns in the West, had yet to develop a “Ladies Mile” – like that on Broadway in New York.

Though to some extent, these daily interactions with rougher Dubuquers, reinforced the performed aspect of their gentility, most of Dubuque’s refined and genteel people separated themselves from Main Street life by building free-standing houses above lower Main Street from the mid-1840s through the 1860s. In this, as in so much, the Langworthys lead the way. Since their arrival, the Langworthys had expressed their private, aloof style very early. Rather than settling in town, like many other miners, and commuting to their mines, they built “comfortable cabins” in Langworthy Hollow and out along the Maquoteka River in 1834. In 1836, their decision to go into business on lower Main Street, necessitated their moving closer to town. Even so, when Lucius Langworthy built a “fine house,” the first frame house in Iowa, it was far beyond the cluster of cabins and frame buildings of the town. Edward Langworthy built a two story brick house in Greek Revival style in 1838 at Fourteenth and Whites Streets, adjacent to which were a fine orchard and gardens. James Langworthy built the second brick house in Iowa in 1838 on Eleventh and Iowa Streets. The “big brick house” was looked on as a “palatial residence” reflecting “pioneer elegance” and was an “ornament to the village.” The house was in the Greek Revival style and was on a large lot surrounded by a stone fence, behind which was an elaborate complex of brick stables and outbuildings and when finished was considered, through the 1840s, “the finest residence in town.” In 1848, Solon Langworthy chose to build a similar house nearby his brothers’ houses. As a result, he seemed to have touched off a building boom of residential construction that would continue into the mid-1850s.Footnote 27

By building their elegant mansions, the Langworthys clearly established the open ground on the northern stretches along and to the east and west of Main Street in the late 1840s, as the “genteel” residential district of Dubuque. The move above Twelfth Street in the late 1840s was, in large part, a response to the northward encroachment of the business section of town on Main Street. During the period, some thirty to forty middle-class professionals, merchants, and capitalists purchased vacant lots and built new houses, each one more refined than the others. All of the houses were built above downtown and Main Street from White Street on the east to the bluffs on the west – Locust Street, and from Seventh to Seventeenth Streets. In 1847, only two years after he had arrived from Virginia, Judge John J. Dyer had established himself “as one of the most prominent and influential citizens of Dubuque” and decided to “build … a large and pretentious house at Main and Thirteenth [streets] with tall … columns like those seen at Mount Vernon” from which “he and his wife dispensed Virginia hospitality.”

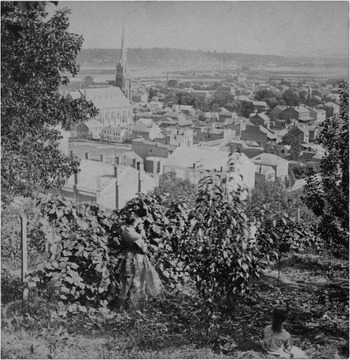

Though some genteel early settlers had established themselves in frame houses above Sixth Street, it was the younger lawyers who, for the most part, joined the Langworthys and Judge Dyer above Eleventh Street in the early 1850s. William J. Barney built a house at Eleventh and Iowa. William B. Allison did the same over at Locust Street and Eleventh. Lincoln Clark established himself in a fine house at Twelfth and Iowa Streets in the early fifties and lived there until he acquired an estate out at Linheim in 1857. Among his legal neighbors were Phineas Crawford over at White and Twelfth to the east and F. E Bissell and D. S. Wilson, on Twelfth Street at Bluff and Locust streets, respectively. Wilson’s brother, following the lead of those wanting to move even further out, owned a large lot of land at Sixteenth and White, on which he built a fine house. Most of these houses are visible in Samuel Root’s later view of the city from the Eleventh Street Bluff (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. “Panoramic View of Dubuque from the Bluff head of 11th Street,” c. 1867, by Samuel Root, Paul C. Juhl Collection, State Historical Society of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa

When John King built an elegant house way north out of town, he pointed the way to next residential pattern. Others followed by building estates out in the country or, as over at Galena and in countless river towns across the West, on the bluffs above town. Though Richard Bonson lived about three miles west of town at Center Grove , his choice to build his house there was related more to his ethnic community there than to any desire to make a social statement. Not so with George Wallace Jones. In 1847, he took a significant step in drawing others onto the bluff, by building an elegant southern style “princely residence” out of town on high ground up Julien Avenue, beyond Ninth Street.Footnote 28

Not surprisingly given his role as a kind of town oligarch, Jones’ new house quickly transformed his “princely residence” on the hill along Julien Avenue (an extension up the bluff of Ninth Street) into a bastion of gentility. As a man of “great energy, general intelligence, suavity, and an attractive manner” that had quickly made him the “Chesterfield gentleman” of the U. S. Senate and Washington society, Jones dazzled Dubuque society and became a “the mark and model” of Dubuque society, and its most sought-after host. When Jones was in town, invitations to his dinners were sought after and valued. In particular, young men in Dubuque eagerly, if anxiously, anticipated “calling” at one of his weekly predominantly male open houses to engage in lively political conversation over an occasional drink and a cigar with Jones and his other guests. Jones was viewed by some as flirtatious, “full of flattery, buncombe, and stories,” and “facile courtesy” and excessive “bowing and scraping” that made him the “pet of women” and the “idol of men.”Footnote 29

Perhaps in response, the Langworthys reasserted their social hegemony in the late 1840s by building new larger houses on the bluffs above the lower town. In 1849 James Langworthy built a large Greek Revival house, with a broad double-level portico, at the corner of James and Langworthy streets, above Second Street, and called it “Ridgemont.” That same year Solon Langworthy built a similar Greek Revival house with a “plantation” portico on a hill facing town way above Third and Locust. Lucius Hart Langworthy soon followed by building a Greek Revival mansion at Hill Street just south of Third. In 1854 Edward built an unusual octagonal house with a tower in the new Italianate style just across from Solon’s house at the corner of Third and Alpine. 1854 also marked the completion nearby on Alta Vista Street at the bluff of James Marsh’s magnificent Italianate mansion, with a tower and solarium, though Harriet Langworthy, his wife for whom he had built the house, died before it was completed. Until the late 1860s when a street railway was built up to the bluff, only others within the family circle built there.

The Langworthy houses, in the words of one booster, vied, “in beauty and architectural design with the most fashionable residences to be found elsewhere.” Clustered within sight of each other and standing like country estates, connected to but separate from the town below, the Langworthy houses on the hill or on “Langworthy bluff” manifested their booster, capitalist, republican, Christian, and genteel values, while also expressing their elite, genteel, even proprietary sense of entitlement and noblesse oblige over the town. The elegantly furnished parlors and dining rooms in their genteel houses formed a network of private venues in which genteel middle-class people could establish an exclusive “social circle” of individuals who were willing to socialize according to the rules of the material and cultural display that defined middle-class gentility.

The fact that Edward went on an extended trip to Europe, an experience that was beginning to become an essential credential of an elite gentleman, in the late forties, established them above other locals. But it was the grounds and gardens around their houses on the bluff that gave them an added impact. With the broad views of Dubuque and the Mississippi River valley and Illinois and Wisconsin beyond, the Langworthys, unlike other genteel families who planted orchards down below, were able to cultivate a kind of genteel romantic “borderlands” gaze or perspective over the town and country around them. Solon Langworthy and his wife Julia Patterson, having encountered this perspective on their honeymoon in 1840 when they stayed at a friend’s suburban house on the bluffs above Cincinnati, particularly cultivated this genteel “borderlands” ethos with an impressive Greek Revival villa, surrounded by farms and open fields to the west, a herd lot, orchards, a large outer garden, a front garden surrounded by a gate, a greenhouse, and a vast front lawn shaded by several great old trees, in front of which ran the road from town out to the nearby Center Grove, all situated on the bluffs with views of Dubuque, evoked this romantic genteel “borderlands” ethos (See Figure 4).Footnote 30

Figure 4. A “Borderlands” View of Business District of Dubuque from a Garden on the Bluffs, c. 1867, by Samuel Root, Paul C. Juhl Collection, State Historical Society of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa