Book contents

- Freud, Jung, and Jonah

- Freud, Jung, and Jonah

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Sources and Translation

- No. 1 Introduction

- No. 2 The First Numbers and the Five Stages of Periodical Publication

- No. 3 The Religious Rise and Fall of the Zentralblatt

- No. 4 Jonah’s Journey across the Nations

- No. 5 The Holy Romanish Moses

- No. 6 Triangles

- No. 7 A Reflection on “the Christian Aeon” and “Us Jews”

- References

- Index

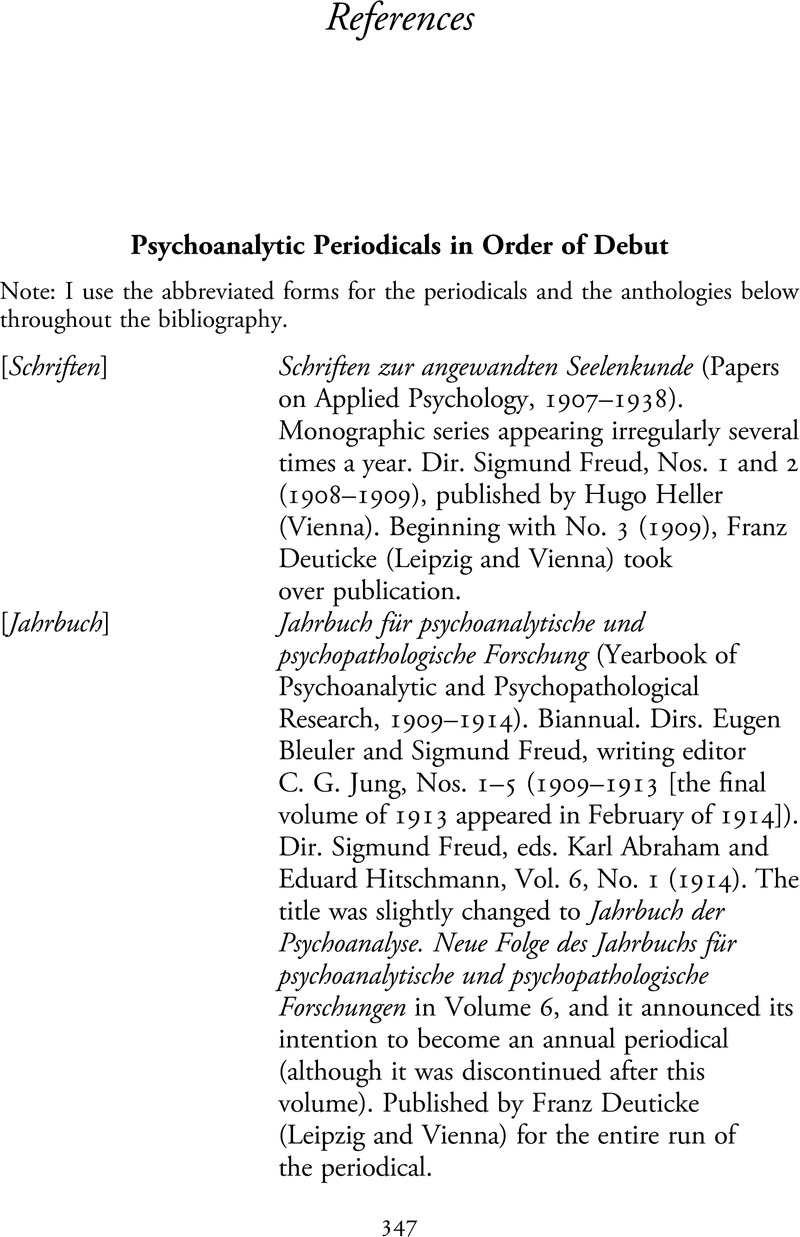

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 December 2022

- Freud, Jung, and Jonah

- Freud, Jung, and Jonah

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Sources and Translation

- No. 1 Introduction

- No. 2 The First Numbers and the Five Stages of Periodical Publication

- No. 3 The Religious Rise and Fall of the Zentralblatt

- No. 4 Jonah’s Journey across the Nations

- No. 5 The Holy Romanish Moses

- No. 6 Triangles

- No. 7 A Reflection on “the Christian Aeon” and “Us Jews”

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Freud, Jung, and JonahReligion and the Birth of the Psychoanalytic Periodical, pp. 347 - 370Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022