Book contents

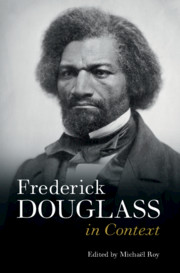

- Frederick Douglass in Context

- Frederick Douglass in Context

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Chronology

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Places

- Part II Genres

- Part III Activism

- Chapter 12 Abolition

- Chapter 13 Temperance

- Chapter 14 Women’s Rights

- Chapter 15 The Civil War

- Chapter 16 Reconstruction and Civil Rights

- Part IV Philosophy

- Part V Networks

- Part VI Afterlives

- Further Reading

- Index

Chapter 14 - Women’s Rights

from Part III - Activism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 June 2021

- Frederick Douglass in Context

- Frederick Douglass in Context

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Chronology

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Places

- Part II Genres

- Part III Activism

- Chapter 12 Abolition

- Chapter 13 Temperance

- Chapter 14 Women’s Rights

- Chapter 15 The Civil War

- Chapter 16 Reconstruction and Civil Rights

- Part IV Philosophy

- Part V Networks

- Part VI Afterlives

- Further Reading

- Index

Summary

Douglass’s women’s rights activism was shaped by his multiple identities and experiences as an enslaved, then free Black man, an abolitionist, an activist and politician, a husband, a father, and a friend. It was also influenced by the various networks through which he navigated. Douglass was both a key figure of antebellum (mostly white) women’s rights meetings and an active participant at the Colored Conventions held regularly throughout the nineteenth century where, alongside abolition and the advocacy of Black rights, the situation of women was often raised in debate. Despite his self-description as a “woman’s-rights-man,” however, the consistency of Douglass’s feminist positions was weakened by the complexities inherent in maintaining a stable reform coalition centered on universal rights before and after the Civil War, when women’s rights were often pitted against racial equality, and the limitations of the early feminist movement, including its all too frequent exclusion of Black women from debates.

Keywords

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Frederick Douglass in Context , pp. 172 - 181Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021