2.1 The Emergence of Rights in the Field of REDD+

As was the case in other domains of climate governance until the second half of the 2000s, human rights issues were not accorded much importance in the initial development of REDD+.Footnote 261 For instance, the UNFCCC COP’s first decision on REDD+ in December 2007 avoided rights-based language and merely acknowledged that “the needs of local and indigenous communities should be addressed when action is taken to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries.”Footnote 262 In addition, the UNFCCC COP failed to recognize the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples under international law in the decision on REDD+ that it adopted in December 2008,Footnote 263 prompting the Indigenous Peoples’ caucus to walk out of the UNFCCC negotiations under the rallying cry “No rights, no REDD.”Footnote 264 Ultimately, as I detail in this chapter, human rights standards have become an integral part of the legal framework for REDD+ developed within the UNFCCC and other international and transnational sites of law such as the World Bank FCPF, the UN-REDD Programme, the REDD+ SES, and the CCBA.

Two main processes can help explain the emergence of rights in the field of REDD+. To begin with, the neglect of human rights concerns in the UNFCCC and the subsequent propagation of REDD+ programs and activities around the world prompted IPOs and NGOs to initiate research and advocacy efforts in this new domain of transnational climate law.Footnote 265 Throughout 2008 and 2009, a growing array of civil society organizations began to press for greater recognition of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+ through a range of actions, including by releasing analysis and reports,Footnote 266 and issuing statements and declarations,Footnote 267 sharing information and coordinating advocacy efforts within civil society networks and caucuses,Footnote 268 and lobbying governments within the UNFCCC, the REDD+ Partnership, the FCPF, and the UN-REDD Programme.Footnote 269 In doing so, IPOs and NGOs most notably sought acknowledgment and protection of the rights enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including the right to free, prior, and informed consent, as well as in the wider set of international instruments that supported the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities.Footnote 270 These efforts eventually succeeded in having Indigenous rights issues included on the agendas of several key international and transnational sites of law for REDD+. These most notably included the UNFCCC, where governments began to incorporate references to Indigenous Peoples, their rights, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in their submissions on draft negotiating texts for REDD+.Footnote 271

In addition, the launch of an extensive array of multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental finance, research, and capacity-building programs also supported the integration of human rights norms across the field of REDD+. Indeed, many actors in these other sites of law were already committed to the protection of human rights in their activities as a result of the spread of rights-based approaches to conservationFootnote 272 and development assistanceFootnote 273 as well as the growing importance accorded to the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the wake of the adoption of the UN Declaration of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 274 In turn, initial experiences with the implementation of REDD+ activities supported by multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental actors generated important insights about the utility of adopting social safeguards to govern the implementation of REDD+ activities. They also elucidated the range of legal obligations and standards by which these safeguards might protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 275 Government officials and civil society representatives reporting on initial experiences with the pursuit of REDD+ on the ground shared these insights across the UNFCCC, the World Bank FCPF, the UN-REDD Programme, and other sites of law through formal and informal channels.Footnote 276

In what remains of this chapter, I analyze the recognition of Indigenous and community rights in the context of three international sites of law (the UNFCCC, the World Bank Forest Climate Partnership Facility, and the UN-REDD Programme) and two transnational sites of law (the REDD+ SES and the CCBA). I conclude by highlighting some of the key differences that have emerged in relation to rights-related issues across these different sites of law.

2.2 Indigenous and Community Rights in UNFCCC Decision-Making on REDD+

2.2.1 The UNFCCC and the Transnational Legal Process for REDD+

The UNFCCC is an international treaty that aims “to stabilize atmospheric concentrations of GHG at a level that would prevent human-induced actions from leading to ‘dangerous interference’ with the global climate system.”Footnote 277 In line with the “convention/protocol” model that is typical of many other multilateral environmental agreements, the UNFCCC establishes a set of common objectives and a forum for intergovernmental cooperation and dialogue on climate change. In turn, it is through the adoption of follow-up protocols that states may develop and take on binding obligations in relation to climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.Footnote 278 As the “supreme body” of the UNFCCC, the COP is tasked with adopting decisions that promote its effective implementation.Footnote 279 The COP meets annually and its decision-making requires the consensus (or near-consensus) of the 196 state parties to the UNFCCC.Footnote 280 Relying upon the scientific and technical guidance provided by its Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA),Footnote 281 the COP adopts decisions that develop and operationalize new legal instruments (such as the Kyoto Protocol) and mechanisms (such as the CDM) in accordance with the UNFCCC’s broader objectives and principles. Over the last two decades, existing research has shown that the legal norms developed through the decisions adopted by the COP have influenced the behavior and interactions of a range of public and private actors operating in the domain of climate change,Footnote 282 under the auspices of the UNFCCCFootnote 283 and beyond.Footnote 284

The UNFCCC has played a critical role in the emergence of the transnational legal process for REDD+ by serving as the primary site for the construction of an initial set of legal norms for REDD+. These legal norms have spread to a variety of sites of law around the world and have prompted the development of myriad multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental schemes, tools, and programs to support jurisdictional as well as project-based REDD+ activities in developing countries.Footnote 285 Although its influence has diminished within a broader transnational legal process that has grown more decentered and heterogeneous since 2007, the UNFCCC has nonetheless remained an important international site of law for jurisdictional REDD+ activities. As part of the Cancun Agreements in 2010,Footnote 286 the Durban Platform in 2011,Footnote 287 and the Warsaw Framework for REDD+ in 2013,Footnote 288 the UNFCCC COP has adopted a series of decisions that provide the core modalities and requirements for the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in developing countries. To be sure, the construction and implementation of these legal norms has been influenced by developments and processes emanating from other sites of law at the international, transnational, and national levels.Footnote 289 All the same, the UNFCCC COP has served as a venue in which legal norms for jurisdictional REDD+ activities have received the endorsement of states through a formalized process in a multilateral setting. As such, a wide range of actors in other sites of law have viewed the decisions of the UNFCCC as providing an authoritative set of international legal norms for the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities.Footnote 290

2.2.2 The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in UNFCCC Decision-Making on REDD+

Although Indigenous Peoples formed an officially recognized caucus within the UNFCCC, the rights of Indigenous Peoples were largely absent from the negotiations and decisions of the UNFCCC COP until the second half of the 2000s.Footnote 291 The only references to rights in the UNFCCC itself are to the rights of states to “exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental and developmental policies” and to “promote sustainable development.”Footnote 292 In particular, the rules and guidance adopted for the implementation of CDM projects under the Kyoto Protocol do not include any references to human rights standards.Footnote 293 Numerous CDM projects, especially large hydro-electric projects, have thus been criticized for encroaching upon the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 294 In fact, the deficient manner in which the UNFCCC’s CDM regime addressed human rights issues prompted the development of private certification programs, such as the CDM Gold Standard, that include standards that recognize and aim to protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 295 While the initial discussions of REDD+ were no exception to the general neglect of human rights issues that characterized the UNFCCC until the second half of the 2000s, Indigenous and community rights eventually became an important aspect of the UNFCCC’s decision-making on REDD+.Footnote 296

The Cancun Agreements, adopted by the UNFCC COP in December 2010, served as the vehicle for the first major decision on REDD+ within the UNFCCC. On the whole, the Cancun Agreements offered unprecedented levels of recognition of the linkages between human rights and climate change.Footnote 297 The preamble to the Cancun Agreements most notably emphasizes that “Parties should, in all climate change-related actions, fully respect human rights.”Footnote 298 As far REDD+ is concerned, the Cancun Agreements specify that a national REDD+ strategy must address “drivers of deforestation and forest degradation, land tenure issues, forest governance issues, gender considerations and [environmental and social safeguards]” in a manner that ensures “the full and effective participation of relevant stakeholders, inter alia, indigenous peoples and local communities.”Footnote 299 Furthermore, the Cancun Agreements provide that the implementation of REDD+ should “promote” and “support” a set of social and environmental safeguards,Footnote 300 including the following two safeguards that are relevant to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities:

(c) Respect for the knowledge and rights of indigenous peoples and members of local communities, by taking into account relevant international obligations, national circumstances and laws, and noting that the United Nations General Assembly has adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples;

(d) The full and effective participation of relevant stakeholders, in particular, indigenous peoples and local communities in [REDD+ activities].Footnote 301

In addition, the Cancun Agreements also include a safeguard that aims to ensure that REDD+ activities serve, among other purposes, to “enhance other social and environmental benefits.” This safeguard includes a footnote that indicates these purposes are to be achieved “[t]aking into account the need for sustainable livelihoods of indigenous peoples and local communities and their interdependence on forests in most countries, reflected in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as the International Mother Earth Day.”Footnote 302 Finally, it is worth noting that the fourth element of a developing country’s readiness for jurisdictional REDD+ consists of the development of an information system for reporting on the way that these and other environmental and social safeguards are “being addressed and respected” in REDD+ activities “while respecting sovereignty.”Footnote 303

Decisions subsequently adopted by the UNFCCC COP have further developed the safeguards regime set out in Cancun and addressed the related issue of incentivizing the provision of “non-carbon benefits” such as poverty reduction. As part of the Durban Platform adopted in December 2011, the UNFCCC COP specified that safeguard information systems must be implemented at the national level for all REDD+ activities “regardless of the source or type of financing”Footnote 304 and through a “country-driven approach” that ultimately provides “transparent and consistent information that is accessible by all relevant stakeholders and updated on a regular basis.”Footnote 305 In the Warsaw Package for REDD+, adopted in November 2013, the UNFCCC COP established that developing countries have to provide periodical summaries of this information to the COP through national communications or some other channel, and on a web platform, on a voluntary basis.Footnote 306 Most significantly, the Warsaw Package provided that developing countries seeking to obtain and receive results-based payments for REDD+ activities are obliged to “provide the most recent summary of information on how all of the safeguards […] have been addressed and respected before they can receive results-based payments.”Footnote 307 Finally, during the Paris Climate Conference held in December 2015, the UNFCCC COP adopted two decisions on REDD+ that relate to Indigenous and community rights. It reaffirmed the importance of incentivizing non-carbon benefits associated with the pursuit of REDD+ and decided that developing countries should be able to seek and obtain support for the integration of such benefits into their jurisdictional REDD+ activities.Footnote 308 The UNFCC COP also reiterated that developing country governments should provide information on how social and environmental safeguards are being addressed and respected “in a way that ensures transparency, consistency, comprehensiveness and effectiveness,” and encouraged them to include information on how each safeguard has been defined, addressed, and respected in the context of national circumstances.Footnote 309

UNFCCC decision-making on the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+ activities has directly and indirectly addressed several types of participatory and substantive rights held by Indigenous Peoples and local communities. A few caveats are worth mentioning, however. With respect to the rights of Indigenous Peoples, the safeguards adopted in Cancun do not specifically refer to the right to free, prior, and informed consent and only “note” the adoption of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 310 With respect to the rights of local communities, the use of the term “members of local communities” suggests that these communities do not hold the sort of sui generis collective rights held by Indigenous Peoples under international law.Footnote 311 More broadly, the UNFCCC safeguards regime for REDD+ is built on the voluntary participation of developing countries and its application is not subject to an independent mechanism.Footnote 312 As a result, IPOs and NGOs have shifted much of their focus to monitoring whether and to what extent developing countries are establishing safeguards information systems and effectively respecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities as part of the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+.Footnote 313

2.3 Indigenous and Community Rights in the World Bank FCPF

2.3.1 The World Bank FCPF in the Transnational Legal Process for REDD+

Launched at the 13th session of the UNCCC in December 2007 and operational since June 2008, the FCPF is a global partnership program of the World Bank.Footnote 314 The FCPF was created to achieve four principal aims: (1) the provision of financial and technical assistance to build the capacity of developing countries to achieve emissions reductions through jurisdictional REDD+ activities; (2) the piloting of performance-based payments for REDD+ activities; (3) experimentation with approaches for sustaining or enhancing local livelihoods and biodiversity conservation through REDD+ activities; and (4) the dissemination of knowledge developed through the FCPF and its experience with supporting REDD+ readiness and jurisdictional activities.Footnote 315 The FCPF comprises two funds for which the World Bank serves as trustee and provides a secretariat: a Readiness Fund that supports developing country capacity-building and preparedness for REDD+ activities and a Carbon Fund to test eventual performance-based payments for emissions reductions generated through REDD+ activities.Footnote 316

As a mechanism for the delivery of finance and capacity-building, the FCPF has been criticized for its ineffectiveness, most notably because of the slow process for the disbursal of funds.Footnote 317 As of June 2016, more than eight years after its launch, thirty-eight countries have managed to sign grant agreements to receive readiness support from FCPF and only thirteen countries have made enough progress in their readiness efforts to be in a position to apply for funding from the Carbon Fund.Footnote 318 On the other hand, the FCPF has emerged as a central international site of law for jurisdictional REDD+ in two respects. First, the set of rules and policies that govern the delivery of finance within the World Bank,Footnote 319 especially those relating to social and environmental safeguards, have not only applied to the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts of FCPF developing country partners, but have also influenced the design of other multilateral and bilateral mechanisms for REDD+.Footnote 320 Second, the FCPF has made significant contributions to the organization, development, and dissemination of knowledge, methodologies, and tools for the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in developing countries.Footnote 321

2.3.2 The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in the World Bank FCPF

The World Bank has traditionally resisted the notion that human rights obligations and principles are applicable to its work based on the notion that political considerations are excluded from its mandate as a multilateral agency focused on economic development.Footnote 322 Unlike many other multilateral and bilateral aid agencies, the World Bank does not have a standalone policy on human rights, nor has it adopted a rights-based approach to development. To the extent that human rights issues are incorporated into the World Bank’s programming, they tend to be conceived in instrumental terms as “a means towards achieving other objectives such as economic development.”Footnote 323 Human rights concerns are specifically addressed at the World Bank through the application of safeguards that aim to prevent, mitigate, and address the adverse environmental and social impacts and risks of the Bank-financed projects.Footnote 324 These safeguards form part of the Operational Policies and Procedures that serve to guide the work of the Bank’s staff. They are also frequently incorporated into the loan agreements that the Bank signs with borrower countries as well as the instruments that govern the mechanisms and trust funds overseen by the Bank.Footnote 325 Their application is monitored by the Inspection Panel, a permanent quasi-judicial body that considers complaints made by groups affected by Bank-financed projects.Footnote 326

The FCPF Charter clearly specifies that the World Bank’s Operational Policies and Procedures apply to the FCPF’s activities, “taking into account the need for effective participation of Forest-Dependent Indigenous Peoples and Forest Dwellers in decisions that may affect them, respecting their rights under national law and applicable international obligations.”Footnote 327 As such, both the jurisdictional readiness efforts of developing countries that are funded through the FCPF Readiness Mechanism and the jurisdictional REDD+ activities and transactions that may be financed by the FCPF Carbon Fund must comply with the World Bank’s set of social and environmental safeguards.Footnote 328 In addition, other multilateral organizations such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and the UNDP that act as delivery partners under the FCPF must “achieve substantial equivalence” to these Operational Policies and their associated procedures under what is known as the “Common Approach.”Footnote 329

Five of these safeguards policies are especially relevant to the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of FCPF. First, Operational Policy 4.10 on Indigenous Peoples (1) requires that the proponents of Bank-funded projects ensure the full and effective participation of Indigenous Peoples and carry out processes of free, prior, and informed consultation, (2) makes the delivery of Bank finance contingent on broad community support among affected Indigenous Peoples for the project, and (3) avoids or minimizes negative effects from the project for Indigenous communities.Footnote 330 Second, Operational Policy 4.01 on Environmental Assessment mandates the consideration of social and environmental aspects in the design, management, and implementation of Bank-funded projects.Footnote 331 Third, Operational Policy 4.11 on Physical and Cultural Resources aims to ensure that Bank-funded projects assist in preserving resources with archaeological, paleontological, historical, architectural, religious, aesthetic, or cultural significance.Footnote 332 Fourth, Operational Policy 4.12 on Involuntary Resettlement aims to avoid or minimize the involuntary resettlement of persons and related impacts from Bank-funded projects.Footnote 333 Finally, Operational Policy 4.36 on Forests seeks to realize the potential of forests for poverty reduction and sustainable economic development and accords “preference to small-scale community-level management approaches where they best reduce poverty in a sustainable manner.”Footnote 334

To the extent that these social and environmental safeguards were created for the delivery of actual projects rather than through a policy development process, their application to a country’s REDD+ readiness phase is not necessarily straightforward.Footnote 335 In order to ensure jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts funded through the FCPF pro-actively respect these safeguards, the FCPF has required participating developing countries to carry out a Strategic and Environmental Assessment (SESA) and produce an Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) as an integral part of their process for applying for funding under the Readiness Mechanism.Footnote 336 A SESA aims “to assess the broader strategic environmental and social impacts, including potential cumulative impacts, which may ensue from future REDD+ activities or projects, and to develop sound environmental and social policies and the necessary safeguards instruments that will apply to subsequent REDD+ investments and carbon finance transactions.”Footnote 337 In practical terms, a SESA involves a combination of diagnostic and consultative activities aimed at contributing to the development of a country’s national REDD+ strategy.Footnote 338 These are intended to ensure that social and environmental safeguards are integrated “at the earliest stage of decision making” and that the strategy itself “reflects inputs from key stakeholder groups and addresses the main environmental and social issues identified.”Footnote 339 In addition, a SESA should result in the adoption of an ESMF that serves as distinct output from a national REDD+ strategy and provides a “framework for managing and mitigating the potential environmental and social impacts and risks related to policy changes, investments and carbon finance transactions in the context of the future implementation of REDD+.”Footnote 340

2.4 Indigenous and Community Rights in the UN-REDD Programme

2.4.1 The UN-REDD Programme and the Transnational Legal Process for REDD+

The UN-REDD Programme is a collaborative initiative jointly established in June 2008 by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).Footnote 341 The central objective of the UN-REDD Programme is to “promote the elaboration and implementation of National REDD+ Strategies to achieve REDD+ readiness, including the transformation of land use and sustainable forest management and performance-based payments.”Footnote 342 The UN-REDD Programme carries out two main sets of activities. It runs a series of “National Programmes” that provide direct financial and technical support to the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts of developing countries.Footnote 343 These programs focus on six key work areas: the development of MRV systems; national REDD+ governance; stakeholder engagement; multiple benefits; REDD+ finance and benefit-sharing; and the transformation of forestry and other relevant sectors.Footnote 344 In addition, the UN-REDD Programme has a global program that seeks to elaborate and disseminate common methodologies and approaches for operationalizing jurisdictional REDD+ based on the experience gained in the readiness efforts of developing countries and in line with the decisions of the UNFCCC COP.Footnote 345

Unlike the FCPF, the UN-REDD Programme was able to launch and operationalize several national programs in developing countries in the early stages of the global rollout of REDD+ in 2009.Footnote 346 However, the support and technical assistance provided by the UN-REDD Programme for jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts has been criticized for the tendency of international staff and consultants to impose their own set of goals and solutions rather than working with developing countries to generate country-driven approaches to the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+.Footnote 347 The effectiveness of the UN-REDD Programme’s contributions to jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts has also been limited by the challenges involved in adapting its plans and activities to an evolving international conception of REDD+, fostering tri-agency collaboration, and coordinating its work with other multilateral and bilateral donors.Footnote 348 While the results achieved by the UN-REDD Programme with respect to supporting the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts of developing countries have generally been underwhelming, the UN-REDD Programme has played an important role in generating and spreading legal norms relating to the core elements of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness.Footnote 349

2.4.2 The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in the UN-REDD Programme

In accordance with the United Nations’ broader commitment to the integration of human rights in its development programming,Footnote 350 the UN-REDD Programme has adopted a “rights-based approach” to its work.Footnote 351 In the early stages of the development of the UN-REDD Programme, its activities were guided by a set of social and environmental principles that reflected its “responsibility to apply a human rights based approach, uphold UN conventions, treaties and declarations, and […] apply the UN agencies’ policies and procedures.”Footnote 352 The principles most notably included the following criteria: “a) All relevant stakeholder groups are identified and enabled to participate in a meaningful and effective manner; b) Special attention is given to the most vulnerable groups and the free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples.”Footnote 353 Accordingly, the UN-REDD Programme therefore provides as follows:

To be eligible for funding, activities at both the national and international level should support the participation of Indigenous Peoples, other forest dependent communities and civil society in national readiness and REDD+ processes in accordance with: (1) the UN-REDD Programme Operational Guidance and social standards; (2) negotiated REDD+ safeguards arrangements; and (3) a country’s commitment to strengthen the national application of existing rights, conventions and declarations.Footnote 354

Although there was some interest, especially among UNDP staff members, in the UN-REDD Programme developing or adopting a set of mandatory standards and safeguards to govern its activities, this approach was not supported by the FAO and the UNEP.Footnote 355 Instead, since March 2012, the activities of the UN-REDD Programme have been governed by a nonbinding set of Social and Environmental Principles and Criteria (SEPC) that were developed through extensive consultations with international experts, development country governments, and stakeholders.Footnote 356 The SEPC are meant to apply to the design, planning, implementation, and monitoring of national REDD+ activities supported by the UN-REDD Programme as well as serve as inspiration for the development of REDD+ safeguards systems by developing country governments participating in a UN-REDD National Programme.Footnote 357 The principles and criteria incorporate commitments drawn from a range of international instruments as well as the interpretative guidance provided by their associated bodies.Footnote 358 The SEPC includes seven principles, and twenty-four associated criteria that lay out associated conditions that the activities of the UN-REDD Programme must meet to respect or fulfil these principles. Some of the principles and criteria most relevant to the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities include the following:

“Principle 1 – Apply norms of democratic governance, as reflected in national commitments and Multilateral Agreements” and the related “Criterion 4 – Ensure the full and effective participation of relevant stakeholders in design, planning and implementation of REDD+ activities, with particular attention to indigenous peoples, local communities and other vulnerable and marginalized groups”;

“Principle 2 – Respect and protect stakeholder rights in accordance with international obligations” and the related “Criterion 7 – Respect and promote the recognition and exercise of the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities and other vulnerable and marginalized groups to land, territories and resources, including carbon”; and

“Principle 3 – Promote sustainable livelihoods and poverty reduction” and the related “Criterion 12 – Ensure equitable, non-discriminatory and transparent benefit sharing among relevant stakeholders with special attention to the most vulnerable and marginalized groups.”

In order to guide UN-REDD staff members, national government civil servants, and stakeholders in the application and monitoring of a government’s SEPC, the UN-REDD Programme has developed a Benefit and Risks Tool (BERT).Footnote 359 The BERT sets out questions that may guide users in the identification of social and environmental risks and opportunities throughout the design, implementation, and monitoring of a UN-REDD National Programme. The BERT includes several questions and related guidance materials from third parties that provide opportunities to highlight and consider the importance of respecting the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in REDD+ activities.Footnote 360 It should be emphasized that the BERT is a new tool that is still being tested and refined by the UN-REDD Programme, in consultation with country partners and stakeholders, and its effectiveness in monitoring adherence to the SEPC is an open question.Footnote 361

In addition, the UN-REDD Programme has developed and released several other tools and guidelines that outline the normative, policy, and operational standards and frameworks that can guide jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities with respect to the participation and rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 362 Three such efforts are particularly worth mentioning. First, the UN-REDD Programme has emerged “as one of the primary instigators and advocates of FPIC in REDD+.”Footnote 363 From 2010 to 2013, the UN-REDD Programme organized an extensive series of regional workshops in Asia, Africa, and Latin America in which multiple stakeholders (developing country governments, IPOs, CSOs, and aid agencies) discussed the challenges and opportunities involved in operationalizing the right to free, prior, and informed consent in the context of REDD+.Footnote 364 These consultations have led to the preparation and release of a set of guidelines that define the elements of free, prior, and informed consent and provide a concrete operational framework for respecting this principle in the context of REDD+ programs.Footnote 365 In accordance with the feedback received from IPOs as well as international lawyers within the UN system,Footnote 366 the guidelines clearly differentiate between the obligations owed to Indigenous Peoples and those owed to forest-dependent communities, recognizing that FPIC primarily applies to the former and only applies to the latter in limited circumstances.Footnote 367

Second, in collaboration with the FCPF, the UN-REDD Programme has produced joint guidelines for stakeholder engagement for jurisdictional REDD+ readiness that set out a step-by-step guide for undertaking consultations, provide a comprehensive overview of relevant international policies on Indigenous peoples and other forest-dependent communities, and offer guidance on how countries should reconcile inconsistent policy commitments between the approach adopted by the UN-REDD Programme and the FCPF.Footnote 368 For the purposes of understanding its implications for the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, the following passage addressing the initiation of participatory processes for REDD+ is worth mentioning:

Special emphasis should be given to the issues of land tenure, resource-use rights and property rights because in many tropical forest countries these are unclear as indigenous peoples’ customary/ancestral rights may not necessarily be codified in, or consistent with, national laws. Another important issue to consider for indigenous peoples and other forest dwellers is that of livelihoods. Thus clarifying and ensuring their rights to land and carbon assets, including community (collective) rights, in conjunction with the broader array of indigenous peoples’ rights as defined in applicable international obligations, and introducing better access to and control over the resources will be critical priorities for REDD+ formulation and implementation.Footnote 369

Third, the UN-REDD Programme has developed a Country Approach to Safeguards Tool (CAST) that enables developing countries to design, plan, and implement a process for the elaboration of social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ as well as the creation of a safeguard information system.Footnote 370 CAST provides a methodology for implementing the Cancun Agreements’ requirement with respect to social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ and is thus meant to serve all developing countries carrying out jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts, whether or not they are partners of the UN-REDD Programme.Footnote 371 CAST is organized as a series of questions that pertain to the different stages in the establishment of social and environmental safeguards for REDD+, and provides a range of sources and guidance materials for, among other things, implementing safeguards information systems or leading stakeholder engagement processes.Footnote 372

2.5 Indigenous and Community Rights in the CCBA

2.5.1 The CCBA and the Transnational Legal Process for REDD+

The CCBA is a nongovernmental standard-setting program that was established in 2003 by Conservation International, CARE International, the Rainforest Alliance, The Nature Conservancy, and the Wildlife Conservation Society with a view to fostering “land management activities that credibly mitigate global climate change, improve the wellbeing and reduce the poverty of local communities, and conserve biodiversity.”Footnote 373 From 2003 to 2005, the CCBA facilitated the drafting of the Climate, Community and Biodiversity (CCB) Standards in order to promote “development of, and investment in, site-based projects that deliver credible and significant climate, community and biodiversity benefits in an integrated, sustainable manner.”Footnote 374 The CCB Standards were subsequently revised in a second edition launched in December 2008.Footnote 375 By 2012, the CCB Standards had become the leading multiple-benefit standard for land-based climate mitigation projects and their use has become standard practice for project-based REDD+ activities.Footnote 376 Since the release of the second edition in 2008, the CCBA had received substantial feedback from project developers and other stakeholders regarding ways to improve and strengthen the CCB Standards.Footnote 377 In response, the CCBA launched a revision process in 2012 to develop a third edition with the specific objective of fostering “market interest and confidence in carbon credits from smallholder- and community-led projects.”Footnote 378 The drafting of the third edition of the CCB Standards from April 2012 to December 2013 employed a participatory and transparent process that entailed the creation of a multi-stakeholder steering committee, a stakeholder mapping exercise, and public exchanges with interested parties.Footnote 379 This time around, the composition of the CCB Standards Committee was expanded to include a second Indigenous member as well as two representatives of non-Indigenous communities.Footnote 380 Moreover, the greater uptake and prominence of the CCB Standards at this point in time meant that the CCBA received much more significant feedback from a broader number and variety of interested parties.Footnote 381

Along with the VCS, the CCBA has emerged as an important transnational site of law for the pursuit of project-based REDD+ activities.Footnote 382 While the CCB Standards do not lead to the issuance of carbon credits,Footnote 383 verification and validation that a REDD+ project has met the CCB Standards will enable that project to tag any carbon credits issued through a carbon accounting standard such as the VCS AFOLU with a CCB label. The CCB Standards thus offer project developers with rules and guidance for the design and implementation of land-based climate mitigation projects “that simultaneously reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions and generate positive impacts for local communities and the local environment”Footnote 384 and, moreover, provide an independent demonstration to potential donors or investors that projects have delivered additional net environmental and social benefits.Footnote 385 As of June 2016, thirty-five REDD+ projects had been fully validated and verified under the CCB Standards, ten REDD+ projects are currently undergoing verification, and fifty-four REDD+ projects have been validated, but not yet verified.Footnote 386

2.5.2 The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in the CCBA

While the first edition of the CCB Standards may have been perceived as inclined toward the environmental objectives of land-based carbon mitigation activities, the third edition of the CCB Standards can be seen as reflecting a sustained and comprehensive focus on human rights and social development.Footnote 387 The third edition of the CCB Standards comprise seventeen required criteria that are divided into four sections covering general matters relating to the establishment of a project, its positive climate impacts, its benefits for communities, and its impacts for the preservation of biodiversity. It also includes three optional requirements relating to the provision of climate adaptation benefits and “exceptional” benefits for communities and biodiversity. When one of these optional requirements is met, a project can be tagged with gold level certification.Footnote 388

The third edition of the CCB Standards applies an expansive approach to the protection of the rights and interests of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. It is primarily concerned with the well-being of “communities” and “community groups.” Communities are defined as “as all groups of people – including Indigenous Peoples, mobile peoples and other local communities – who derive income, livelihood or cultural values and other contributions to well-being from the Project Area at the start of the project and/or under the with-project scenario.”Footnote 389 Community groups are described “as sub-groups of Communities whose members derive similar income, livelihood and/or cultural values and other contributions to well-being from the Project Area and whose values are different from those of other groups; such as Indigenous Peoples, women, youth or other social, cultural and economic groups.”Footnote 390 The CCB Standards also include consideration of groups known as “other stakeholders,” defined as “all groups other than Communities who can potentially affect or be affected by the project activities and who may live within or outside the Project Zone.”Footnote 391

The CCB Standards incorporate Indigenous and community rights in four important ways. First, the CCB Standards include a criterion requiring the full and effective participation and consent of affected communities and stakeholders:

Communities and Other Stakeholders are involved in the project through full and effective participation, including access to information, consultation, participation in decision-making and implementation, and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (…). Timely and adequate information is accessible in a language and manner understood by the Communities and Other Stakeholders. Effective and timely consultations are conducted with all relevant stakeholders and participation is ensured, as appropriate, of those that want to be involved.Footnote 392

This criterion most notably includes specific and comprehensive indicators relating to participatory rights, including access to information, consultation, participation in decision-making, and grievance procedures.Footnote 393 In addition, this criterion contains an indicator on anti-discrimination, and requires a description of “the measures needed and taken to ensure that the project proponent and all other entities involved in project design and implementation are not involved in or complicit in any form of discrimination or sexual harassment with respect to the project.”Footnote 394

Second, the CCB Standards provide enhanced protections for the customary land and resource rights of local communities. They mandate that the free, prior, and informed consent of “relevant Property Rights Holders has been obtained at every stage of the project”Footnote 395 (from design to implementation), in line with the comprehensive guidance that is now included among its indicators.Footnote 396 They also require that project developers ensure their project “respects and supports rights to lands, territories and resources, including the statutory and customary rights of Indigenous Peoples and others within Communities and Other Stakeholders.”Footnote 397 In particular, the CCB Standards require project developers to “[d]escribe and map statutory and customary tenure/use/access/management rights to lands, territories and resources in the Project Zone including individual and collective rights and including overlapping or conflicting rights,” “describe measures needed and taken by the project to help to secure statutory rights,” and “[d]emonstrate that all Property Rights are recognized, respected, and supported.”Footnote 398

Third, the CCB Standards require that projects generate “net positive impacts on the well-being” of affected communities.Footnote 399 Project developers must therefore evaluate the direct and indirect benefits, costs, and risks of a project for communities living within the project area, carry out measures to mitigate any negative impacts, and demonstrate that the net well-being impacts of a project are positive for groups within affected communities.Footnote 400 The CCB Standards also mandate that projects must “do no harm” to the well-being of other stakeholders.Footnote 401 The evaluation of well-being in this context is explicitly restricted to compliance with statutory or customary rights.Footnote 402 In addition, project developers seeking certification under the CCB Standards must develop and implement a monitoring plan to evaluate the project’s impacts on the well-being of communities and stakeholders as well as the effectiveness of measures adopted to maintain or enhance community well-being.Footnote 403

Finally, the CCB Standards include two optional criteria that further advance the rights and interests of local communities. The optional criterion in climate benefits mandates that projects identify and implement strategies to assist communities in adapting to the impacts of climate change.Footnote 404 Most importantly, the third edition of the CCB Standards includes an optional criterion on exceptional community benefits that applies only to projects that are either led by communities or are explicitly aimed at reducing poverty.Footnote 405 This criterion is focused on the equitable sharing of benefits with as well as within communities.Footnote 406 The indicators related to this criterion include a special focus on demonstrating net positive impacts, in terms of well-being and increased levels of participation in decision-making, for marginalized or vulnerable communities, marginalized or vulnerable members of communities, and women.Footnote 407

2.6 Indigenous and Community Rights in the Redd+ SES

2.6.1 The REDD+ SES and the Transnational Legal Process for REDD+

The REDD+ Social and Environmental Safeguards (REDD+ SES) is a multi-stakeholder initiative launched in May 2009 to develop a set of voluntary social and environmental safeguards for government-led REDD+ programs and activities.Footnote 408 The purpose of the REDD+ SES is to “support the design and implementation of REDD+ programs that respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and generate significant social and biodiversity benefits.”Footnote 409 The development and application of the REDD+ SES is overseen by an international secretariat provided by the Community, Climate & Biodiversity Alliance (CCBA) and CARE International, with the support of the ProForest Initiative.Footnote 410 A first version of the REDD+ SES was developed in 2009 and 2010 through an iterative process involving workshops and consultations bringing together representatives from governments participating in or contributing to REDD+ readiness efforts, international and non-governmental organizations, Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities, and the private sector.Footnote 411 A second version released in September 2012 drew on early experiences with the application of the REDD+ SES, the comments received from a range of stakeholders, and the guidance on safeguards provided by the UNFCCC.Footnote 412 The proponents of the REDD+ SES argue that it offered added value due to three considerations: (1) the safeguards were developed through an inclusive multi-stakeholder process that has provided them with a high level of credibility; (2) they go beyond risk-mitigation to promote the multiple benefits achievable through REDD+; and (3) they provide a broad and flexible framework for meeting the requirements set by a wide range of standard-setting bodies for REDD+.Footnote 413 The REDD+ SES has also served as an important site for developing and sharing insights on the interpretation and application of safeguards in the context of the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities.Footnote 414

The REDD+ SES apply to a broad range of jurisdictional REDD+ activities, including “government-led programs implemented at national or state/provincial/regional level and for all forms of fund-based or market-based financing.”Footnote 415 The REDD+ SES provide a voluntary set of social and environmental standards as well as a methodology for developing country governments looking to interpret and apply international guidance on REDD+ safeguards and to build capacity in this aspect of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness.Footnote 416 Several jurisdictions have thus far voluntarily decided to participate in the development or implementation of the REDD+ SES, most notably the State of Acre in Brazil, the Province of Central Kalimantan in Indonesia, Ecuador, Nepal, and Tanzania.Footnote 417 In November 2015, the State of Acre became the first jurisdiction to have completed all ten steps of the REDD+ SES and have received a certificate of approval from the REDD+ SES Initiative Secretariat.Footnote 418

2.6.2 The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in the REDD+ SES

The REDD+ SES are comprised of eight principles and thirty-four criteria and related indicators that set expectations for the achievement of high social and environmental performance in the context of jurisdictional REDD+ activities. Most of the REDD+ SES can be seen as broadly supportive of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. On the whole, the REDD+ SES apply to “rights holders,” defined as “those whose rights are potentially affected by the REDD+ program, including holders of individual rights and Indigenous Peoples and others who hold collective rights.”Footnote 419 Five of the eight principles in the REDD+ SES are specifically designed to ensure the recognition and protection of a range of participatory and substantive rights:

“The right to lands, territories and resources are recognized and respected” (principle 1);

“The benefits of the REDD+ program are shared equitably among all relevant rights holders and stakeholders” (principle 2)

“The REDD+ program improves long-term livelihood security and well-being of Indigenous Peoples and local communities with special attention to the most vulnerable people” (principle 3);

“All relevant rights holders and stakeholders participate fully and effectively in the REDD+ program” (principle 6); and

“All rights holders and stakeholders have timely access to appropriate and accurate information to enable informed decision-making and good governance of the REDD+ program” (principle 7).

Furthermore, the criteria and indicators in REDD+ SES most notably mandate the following requirements for jurisdictional REDD+ programs:

identification of different rights and rights-holders, including through an inventory and mapping exercise (criteria 1.1);

recognition of, and respect for, the “statutory and customary rights to lands, territories and resources which Indigenous Peoples or local communities have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired” (criteria 1.2);

application of “free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples and local communities for any activities affecting their rights to lands, territories and resources” (criteria 1.3);

allocation of private carbon rights (where applicable) on the basis of the “statutory and customary rights to the lands, territories and resources” that generated the emissions reductions (criteria 1.4);

establishment of “[t]ransparent, participatory, effective and efficient mechanisms” for “equitable sharing of benefits of the REDD+ program among and within relevant rights holder and stakeholder groups” (criteria 2.2);

generation of “additional, positive impacts the long-term livelihood security and well-being of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, with special attention to women and the most marginalized and/or vulnerable people” (criteria 3.1);

ensuring that all “relevant rights holder and stakeholder groups that want to be involved in REDD+ program design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation are fully involved through culturally appropriate, gender sensitive and effective participation” (criteria 6.2);

respect and support for and protection of “rights holders’ and stakeholders’ traditional and other knowledge, skills, institutions and management systems including those of Indigenous Peoples and local communities” (criteria 6.3);

identification and use of “processes for effective resolution of grievances and disputes relating to the design, implementation and evaluation of the REDD+ program, including disputes over rights to lands, territories and resources relating to the program” (criteria 6.4); and

compliance with applicable international conventions (criteria 7.1), including those relating to the “human rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities” (indicator 7.1.2).

In addition to this set of social and environmental safeguards, the REDD+ SES provides guidelines that establish the steps that must be followed by developing countries that want to use and apply the REDD+ SES as part of their jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts. Under the guidance of a Standards Committee formed in each jurisdiction, governmental and nongovernmental technical experts facilitate a multi-stakeholder process for the country-specific interpretation and assessment of the REDD+ SES. This process is meant to result in the creation of indicators tailored to local laws, realities, and institutions, and the establishment of a locally relevant, accountable, and transparent assessment mechanism.Footnote 420 Because the REDD+ SES is consistent with the UNFCCC guidance on safeguards and the safeguards applied by the World Bank and the UN-REDD Programme, the information gathered through a REDD+ SES assessment may be integrated into reports and communications submitted to a variety of multilateral, bilateral, and private donors. In addition, the REDD+ SES has developed an international review mechanism whereby independent experts assess the extent to which a country has followed REDD+ SES guidance, evaluate and offer feedback on the process followed to use REDD+ SES at the country level, and identify lessons and good practices that may be useful to other jurisdictions.Footnote 421

2.7 Heterogeneity in the Recognition of Indigenous and Community Rights in International and Transnational Sites of Law for REDD+

Opinions on how these different sites of law have performed in respecting and ensuring respect for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities continue to be divided among scholars and activists. To be sure, the legal norms developed in many sites of law, especially the UNFCCC and the World Bank FCPF, fall short of fully incorporating the rights enshrined in the UNDRIP or recognized by international and regional human rights bodies. Yet, compared with the reluctance of many actors to accord any importance to human rights issues in the initial stages of the development of REDD+, the final set of Indigenous and community rights recognized across these sites of law reflects a clear evolution in the legal norms constructed for REDD+ as well as an important development more broadly, given the traditional reluctance of multilateral institutions and conservation NGOs to apply human rights norms to their activities.

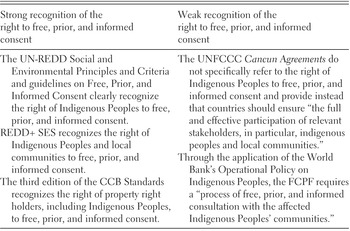

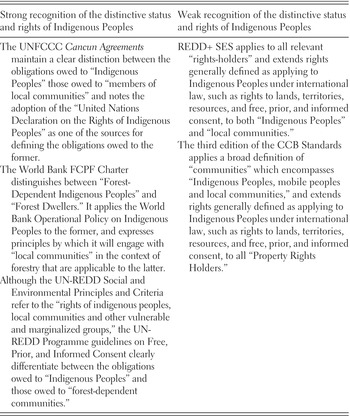

Yet the processes by which legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities surfaced within international and transnational sites of law for REDD+ have not been free from controversy, however, nor have they yielded a homogenous set of outcomes. As can be seen from Tables 2.1 and 2.2, important divergences have most notably emerged in the treatment of the right to FPIC as well as the distinctive status held by Indigenous Peoples across international and transnational sites of law. While the UN-REDD Programme Social and Environmental Principles and Criteria, the REDD+ SES, and the third edition of the CCB Standards offer strong support for the right to FPIC, the UNFCCC Cancun Agreements and the World Bank’s Operational Policy on Indigenous Peoples do not. At the same time, the UNFCCC Cancun Agreements, the World Bank’s Operational Policies, and the UN-REDD Programme Social and Environmental Principles and Criteria maintain a clear distinction between the obligations owed to Indigenous Peoples and non-indigenous local communities, whereas the REDD+ SES and the third edition of the CCB Standards appear to do away with this distinction altogether.

Table 2.1 Variations in the recognition of the right to free, prior, and informed consent in international and transnational sites of law for REDD+

Table 2.2 Variations in the recognition of the distinctive status of Indigenous Peoples in international and transnational sites of law for REDD+

The recognition and operationalization of human rights norms across sites of law reflects different balances that have been struck between the effectiveness of REDD+ and its implications for justice and equity.Footnote 422 On the whole, the social safeguards for REDD+ adopted within the UNFCCC, the World Bank FCPF, and the UN-REDD Programme represent a series of compromises between actors pressing for the protection of human rights and those concerned with preserving the sovereignty of developing countries and not “over-burdening” their efforts to operationalize jurisdictional REDD+ initiatives at the domestic level.Footnote 423 The recognition of Indigenous and community rights even proved controversial in the context of a voluntary certification scheme like the CCBA, which was specifically developed to ensure that carbon sequestration projects would deliver multiple and significant social benefits beyond compliance with international law.Footnote 424 In this regard, there is little doubt that the participatory, multi-stakeholder approach underlying the development of the CCB Standards (as well as the REDD+ SES) has provided unique opportunities for adopting stronger rights and protections for Indigenous Peoples and local communities than the consensus-based, state-centered multilateral processes and all of the political compromises that they required on such a sensitive issue.Footnote 425

Finally, the recognition of human rights in the field of REDD+ has also been affected by the mediating influence of existing legal norms present in different sites of law. A comparison of the differing approaches of the World Bank FCPF and the UN-REDD Programme to the recognition of rights is illustrative of the influence of existing legal norms. Specifically, the UN-REDD has adopted a rights-based approach that is consistent with the United Nation’s approach to human rights issues. It accordingly refers to the more recent definition of FPIC included in the UNDRIP. By contrast, the World Bank FCPF has stuck with the Bank’s risk-based perspective and maintains its Operational Policy on Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 426

As I will demonstrate in subsequent chapters, these variations in the recognition of Indigenous and community rights have created significant opportunities for the translation of rights in national and local sites of law for REDD+. Indeed, the heterogeneous manner in which these rights have been recognized have enabled government officials, activists, lawyers, project developers, and communities to develop innovative interpretations and applications of these rights across different contexts.