In this concluding chapter, I begin by discussing the significance and limitations of my findings regarding the complex relationship between the transnational legal process for REDD+ and the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. Next, I identify the questions and implications that my findings raise for scholarship on REDD+ as well as the nature and influence of transnational legal processes. I conclude by addressing the implications of this book for practitioners and activists working to build synergies between the pursuit of REDD+ and the promotion of human rights.

Significant Findings on Redd+ and Rights

The significance of my research on the complex relationship between REDD+ and Indigenous and community rights can be summed up in the following five conclusions. First, the emergence and spread of REDD+ across sites and levels of law has functioned as an opportunity for multiple actors to shape the conveyance and construction of legal norms that recognize and protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. My findings suggest that the transmission of legal norms relating to REDD+ has functioned as something of an exogenous shock that has disrupted the traditional patterns of the development and implementation of legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in several sites of law. In the UNFCCC and Indonesia, the transnational legal process for jurisdictional REDD+ activities led to the recognition of the rights and status of Indigenous Peoples – at least within the domain of REDD+ – for the first time. In Tanzania, efforts to operationalize jurisdictional REDD+ reinforced the rights of forest-dependent communities in the National REDD+ Strategy and expanded these rights to include FPIC in the context of its safeguards policy. As far as project-based REDD+ activities are concerned, REDD+ served as a vehicle for NGOs to operationalize and implement their existing commitments to rights-based approaches to conservation and development through the development of the CCB Standards and the REDD+ SES. In turn, the emergence of a voluntary market for REDD+ dominated by development agencies and corporate social responsibility initiatives as well as animated by emerging norms concerning the importance of rights to the effectiveness of REDD+ led many project developers to respect and enhance the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities at the local level.

It is important to stress that the transnational legal process for REDD+ has not been a panacea for Indigenous Peoples and local communities. For one thing, across several sites of law such as the UNFCCC, the World Bank, Indonesia, and Tanzania, I found that the construction of legal norms for REDD+ did not fully reflect the expectations and demands of IPOs and NGOs pushing for greater recognition and protection of Indigenous and community rights. I even uncovered situations in which REDD+ projects had not respected the rights of local communities and concluded, moreover, that the policy processes and outcomes relating to the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Tanzania were not consistent with international standards relating to the protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples. For another, I found that the influence of the transnational legal process for REDD+ was generally mediated by resilient endogenous norms and politics that prevailed in sites of law. One illustration of the limited effect of REDD+ is Tanzania, where the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities did not lead government officials to alter their traditional opposition to the concept of Indigenous Peoples. As well, the emergence of REDD+ in the context of the World Bank’s creation of the FCPF did not alter the Bank’s traditional positions on matters relating to FPIC, where it was defined as an entitlement to be consulted, rather than a right to consent. Most importantly, the exogenous legal norms relating to Indigenous rights that were conveyed to many sites of law ultimately engendered the construction of hybrid legal norms. This is most notably reflected in the ways that the rights of Indigenous Peoples have been translated in the jurisdictional REDD+:activities pursued in Indonesia and Tanzania. In Indonesia, the distinctive status and rights of Indigenous Peoples were recognized alongside those of local communities. In Tanzania, the rights of Indigenous Peoples were interpreted as applying to a broader category known as “forest-dependent communities.” In sum, although REDD+ has provided meaningful opportunities for the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities across various sites of law, these opportunities have not been transcendent, but have instead been shaped by the interplay of exogenous and endogenous factors.Footnote 951

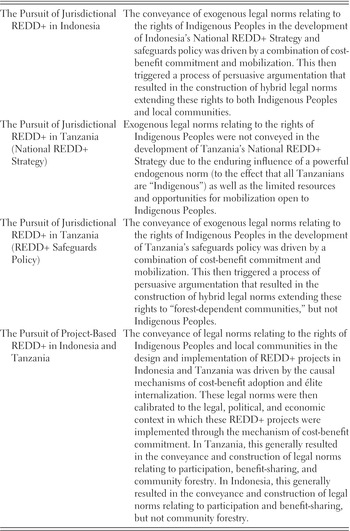

Second, as is summarized in Table C.1, the transnational legal process for REDD+ has offered multiple causal pathways for the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities across multiple sites of law. These different pathways unfolded through different sequences and combinations of rationalist and constructivist causal mechanisms and factors. They reveal the critical role that diversity has played in the diffusion of rights in the field of REDD+. Across different sites of law, I found that a multiplicity of public and private actors were committed to building linkages between human rights and REDD+, that they had varying reasons for doing so, and that they deployed a variety of strategies and modes of influence to shape the construction, diffusion, and implementation of rights in the context of REDD+. Moreover, the pluralism of the transnational legal process for REDD+ made it possible for these actors to exert influence, from above and from below, across multiple sites of law that offered different opportunities for the conveyance and construction of rights. This diversity was important not only because it increased the probable activation of the causal mechanisms of conveyance and construction, but also because these mechanisms complemented one another in concurrent or sequential ways.Footnote 952

Table C.1 The pathways for the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities provided by the transnational legal process for REDD+ across multiple sites of law

The third insight offered by this book focuses on the important role played by timing in the conveyance and construction of legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+.Footnote 953 There are numerous broader historical developments that have increased the likelihood that the transnational legal process for REDD+ might serve as a vehicle for the promotion of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities. To begin with, the treatment of human rights issues by activists and policy-makers in the transnational legal process for REDD+ was influenced by earlier negative experiences with the CDM. The significant human rights issues that came to light in the context of the CDM in the 2000s highlighted the importance of advocating for, and developing, mechanisms to prevent and mitigate the negative social and environmental impacts associated with climate mitigation initiatives.Footnote 954

In addition, REDD+ has emerged at a time that has been relatively more favorable for the promotion of Indigenous and community rights in environmental governance. The global emergence of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007 has significantly affected the trajectory of the transnational legal process for REDD+, providing actors with increased awareness of the importance of Indigenous rights and offering an important set of symbols and international commitments that have supported the conveyance of these rights across multiple sites of law.Footnote 955 In addition, the visibility of the rights of local non-Indigenous communities has also increased considerably during this time, as is reflected in the emergence of a rights-based policy agenda in conservation as well as broader trends in the devolution of forest management, tenure, and resource rights in many developing countries, especially in Latin America.Footnote 956 More broadly, the growing importance of human rights to the fields of climate changeFootnote 957 and conservationFootnote 958 has also facilitated the integration of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in various international and transnational sites of law for REDD+. At the national level, the pursuit of REDD+ in Indonesia and Tanzania followed periods in which these countries had initiated a transition toward decentralization and democratization, which made the very mobilization of endogenous interest groups more likely.Footnote 959

The fourth conclusion that I draw is that the recognition and implementation of the participatory rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (such as rights to full and effective participation or to FPIC) appear to have been relatively more effectual than the recognition and implementation of their substantive rights (such as rights to forests, land tenure, resources, or livelihoods). As far as the international and transnational levels are concerned, the UNFCCC largely focuses on participatory rights and the CCBA only provides for the promotion of substantive rights in an optional criterion of the CCB Standards. In Indonesia, the National REDD+ Strategy and the safeguards policy recognize both sets of rights, but it remains to be seen whether Indigenous Peoples and local communities will succeed in having their customary forest and land tenure rights recognized and protected in practice. Indeed, the underwhelming results of REDD+ projects in this second regard suggest that this is far from inevitable. Tanzania is perhaps the only context in which I found evidence of the participatory and substantive rights of local communities being recognized and implemented in new and meaningful ways through jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities (albeit with the general exclusion of Indigenous Peoples). Of course, it is important to recall that whereas the protection of substantive rights may have been thwarted by the power asymmetries that underlie forest governance in Indonesia, the promotion of community forestry did not threaten powerful economic interests in Tanzania as such.

These broader trends, in which participatory rights have seemingly been given priority over substantive rights and the recognition of rights may ultimately have been subordinated to powerful interests, give a certain level of credence to some of the expectations of scholars regarding the limitations of REDD+ for the protection of human rights. If REDD+ has led to the recognition and implementation of the rights of communities to participate in, and consent to, the design and operationalization of REDD+, while neglecting their substantive rights to access, govern, and benefit from forests or carbon sequestration, this would reflect the preponderant influence of the “uneven playing field” that, many scholars argue, defines the context in which REDD+ has been pursued.Footnote 960 Then again, it is also possible that the recognition of these participatory rights could provide the basis for the development of “rights consciousness” and assist communities in mobilizing for the recognition and protection of their substantive rights in the long-term.Footnote 961 As such, understanding the lasting consequences of REDD+ for Indigenous and community rights will require future research focused on the implementation of policies, programs, and projects on the ground.

Fifth and finally, my book has demonstrated that REDD+ constitutes a paradox for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in ways that were not expected by scholars and practitioners. The original REDD+ paradox identified by Sandbrook et al., pertained to the fact that the funding generated through REDD+ had the capacity to generate benefits for forest-dependent communities (through the implementation of community forestry and benefit-sharing arrangements), while also posing significant risks for their rights, institutions, and livelihoods (due to corruption, graft, élite capture, and land-grabbing).Footnote 962 While confirming that REDD+ may operate in this Janus-like manner, my book also unearths two additional paradoxes.

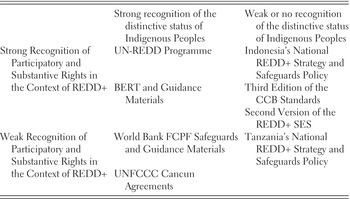

To begin with, I argue that REDD+ has amounted to a paradox for Indigenous Peoples in particular because there appears to be an underlying tension between the appreciation of their distinctive rights and status and the progressive recognition and expansion of the rights of forest-dependent communities. Indeed, as can be seen from Table C.2, the sites of law in which Indigenous Peoples have succeeded most clearly in having their distinctive status and rights recognized – such as the UNFCCC and the World Bank FCPF – tend to be the sites of law that have accorded the least expansive applications of participatory and substantive rights in the context of REDD+. Conversely, in the sites of law that have offered greater protections for the participatory and substantive rights traditionally held by Indigenous Peoples – such as the CCBA, the REDD+ SES, and Indonesia’s REDD+ Safeguards – these rights have been extended to non-Indigenous local communities as well. What is more, although the development of Tanzania’s jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities may have led to some gains in terms of the recognition and promotion of rights such as FPIC, these rights were extended to forest-dependent communities to the exclusion of Indigenous Peoples. As such, while REDD+ may have led to the conveyance and construction of community rights across multiple sites of law, it may not have contributed much to the formalization of the collective identities and associated rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 963

Table C.2 The recognition of the distinctive status of Indigenous Peoples and participatory and resources rights in the transnational legal process for REDD+

The second paradox that I have identified in this book concerns the apparent tension between the effectiveness of REDD+ as an intervention designed to reduce carbon emissions from forest-based sources and its effects on the recognition and protection of human rights. I do not mean to say that there is an inherent trade-off between the broader effectiveness of REDD+ and the protection of human rights. Rather, the insight that I have uncovered is that it is perhaps the very ineffectiveness of REDD+ as a policy instrument that has provided unexpected opportunities for the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

From 2009 to 2014, with the support provided by multiple international actors, government officials in Indonesia and Tanzania carried out a complex program of policy development and capacity-building to support the operationalization of jurisdictional REDD+ in their countries. Due to the size and importance of its forest carbon stocks and the enthusiasm and leadership of President Yudhoyono, the pursuit of REDD+ in Indonesia attracted considerable amounts of funding and attention from multilateral institutions, foreign governments, NGOs, and the private sector. As a result, Indonesia has made considerable progress in establishing a REDD+ Agency and has designed many of the elements required to implement jurisdictional REDD+ at the national level, such as a national strategy, a financial mechanism, an MRV system, and a safeguards policy and information system.Footnote 964 Despite millions of dollars in aid money, a slew of international consultants, and an endless series of meetings, consultations, and workshops, Tanzania had only partially achieved one of the requirements of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness mandated by the Cancun Agreements, namely the development of a National REDD+ Strategy, by September 2014. Tanzania still lacks a REDD+ finance mechanism, a national reference emission level or forest reference level, a system for measuring, reporting, and verifying emissions reductions, and an information system for reporting on the application of social and environmental safeguards. It is not clear that Tanzania will be ready to participate in a global REDD+ mechanism any time soon.Footnote 965 In any case, although Indonesia has reached a more advanced stage than Tanzania in its jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities, it is striking that the efforts of the last seven years have not actually led to significant reductions of carbon emissions in either country.

Although the challenges of implementing jurisdictional REDD+ activities are now obvious, these limited results are nonetheless disappointing, especially in comparison with the initial enthusiasm that greeted the emergence of REDD+ in 2007. On the whole, the complexity of jurisdictional REDD+ and the multiple actors and initiatives that were developed to support the readiness efforts of developing countries appear to have created a unique and unexpected opportunity for the promotion of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Two of the core elements of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness – the development of a national strategy and the creation of safeguards information systems – along with the need for technical assistance and the related practice of organizing multi-stakeholder consultative processes have engendered significant openings for local and transnational actors to press for the recognition of human rights in the context of REDD+. In a more indirect fashion, the complexity of designing forest emissions levels, MRV systems, and benefit-sharing schemes required pilot projects as well as lengthy programs of technical assistance that have provided additional time and opportunities for mobilization and persuasive argumentation across sites and levels of law. One can imagine that if the domestic operationalization of REDD+ had simply entailed unconditional payments meant to facilitate the adoption of policies to reduce deforestation by developing countries, this would not have offered as much scope for the conveyance of human rights norms.

The experience of REDD+ projects tells a similar story. A slew of conservation and development NGOs and corporations have spent millions in public and private funding to design and carry out REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania. While some of these projects have contributed to the sustainable management of forests in significant ways, only two of the thirty-eight REDD+ projects in these two countries have actually obtained certification as a REDD+ project under the VCS and CCB programsFootnote 966 and only two other projects have managed to prepare and submit a project design document for validation and verification by third-party auditors under these programs.Footnote 967 It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss all of the challenges that REDD+ projects have faced in successfully reducing carbon emissions at the local level and in obtaining dual certification under the VCS and CCB. My research on the development and implementation of REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania does suggest, however, that the low price of carbon on voluntary carbon markets has been an important barrier to the development of REDD+ projects. At the same time, this appears to have tilted the broader REDD+ market toward standards and projects that aim to empower local communities with respect to their rights and authority over forests.Footnote 968 As such, the very ineffectiveness of the voluntary carbon market has made it possible for REDD+ projects to deliver important social benefits, even as their ability to significantly reduce carbon emissions has not lived up to initial expectations.

This second REDD+ paradox is rather ironic, when judged in light of the concerns initially expressed over the potential risks posed by REDD+ for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Indeed, the very same features of REDD+ that many scholars and activists saw as flaws – its technocratic focus on the reduction of carbon emissions and the measurement of carbon stocks, its use of “nonbinding” safeguards, its focus on national-level institution-building, and its reliance on markets – appear to have provided unexpected and meaningful opportunities for its redemption with respect to its effects on rights, though perhaps not in terms of forests or the climate.

Limitations

I must acknowledge three important limitations in my study of the transnational legal process for REDD+ and the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. The first limitation has to do with periodization.Footnote 969 As Campbell points out, different time frames may privilege different types of explanations, given that causal processes driven by interests tend to unfold in a shorter time frame than those driven by norms.Footnote 970 The period that I studied in my process-tracing runs from the initial emergence in 2005 of the concept that would later become REDD+ in the UNFCCC to the fall of 2014. The latter date was chosen to identify a clear “cut-off time” for what is a constantly evolving and unfolding phenomenon. Indeed, the causal processes associated with the construction and conveyance of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the transnational legal process for REDD+ have not yet reached their endpoints and will continue to evolve in the near future. Although my book has traced the conveyance and construction of rights across multiple sites and levels of law for REDD+ during the course of almost a decade, it is still too early to fully assess whether and how these legal norms have been implemented on the ground. While I have offered some hypotheses about the future prospects for the implementation of rights in the context of the jurisdictional REDD+ activities of Indonesia and Tanzania as well as the broader voluntary market for REDD+, additional research will be needed to assess whether and how these rights may affect, in practical terms, the lives and interests of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The second limitation has to do with the challenges and constraints of process-tracing as a research method. In their recent book on process-tracing, Beach and Pederson suggest that it is essentially impossible to live up to the standards of causal inference implied by process-tracing.Footnote 971 To be sure, the collection and interpretation of additional evidence could have strengthened the internal validity of my causal claims. Most importantly, while process-tracing is feasible as well as appropriate in research designs involving a small number of cases, it not necessarily well-suited to explaining phenomena that involve a large population of cases.Footnote 972 As such, process-tracing only enabled me to make provisional claims about the conveyance and construction of rights across REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania.Footnote 973 In this second regard, it is clear that a full understanding of how REDD+ projects have affected the recognition and protection of the rights of local populations, especially in terms of their effects on livelihoods, local access to forests and resources, and development of rights consciousness, requires additional and different research methods, including ethnography, household surveys, and rapid rural appraisals. These methods would be especially useful for studying how rights have influenced, if at all, the evolution of community systems of forest and land governance at the local level.

The third limitation has to do with the types of rights that I did not study in this book. In particular, gender-related rights stand out as a missing element in my analysis. Admittedly, the implications of REDD+ on the rights of women were not a particularly important or salient issue across any of the sites of law that I studied, with the exception of the CCB Standards, which do include some legal norms relating to the prohibition of discrimination and the empowerment of women. Yet, given the dynamics of the exclusion and marginalization of women within Indigenous and rural communities in many contexts, there is no reason to think that these rights were not important for ensuring the effective and equitable pursuit of jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities.Footnote 974 Other particular types of rights that do not explicitly feature in my analysis include labor rights and rights to freedom from discrimination.Footnote 975 Put differently, this book avoids answering a different, yet equally important, question: why were some human rights norms, notably women’s rights, not constructed and conveyed within and through the transnational legal process for REDD+?

Future Research on REDD+ and Rights

This book suggests four promising lines of inquiry for future scholarship focused on the pursuit of REDD+ and the protection of human rights in developing countries. A first line of inquiry could extend the research in this book by studying the conveyance and construction of rights in other sites of law in the transnational legal process for REDD+. In this book, I have argued that REDD+ provided an opportunity for the conveyance and construction of rights in the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness processes and REDD+ project-based activities pursued in Indonesia and Tanzania. I have also offered explanations about the particular causal pathways through which this process unfolded and the variations in the recognition and protection of rights that resulted therefrom. While process-tracing is not meant to offer claims that can be generalized to a population of cases, it does offer key lessons about the role of causal mechanisms that can be studied in other cases. Each of the key findings about the construction and conveyance of rights in the transnational legal process for REDD+ in Indonesia and Tanzania provide hypotheses that could be assessed in future research.

Some of the additional sites of law that could be studied through in-depth process-tracing might include international sites of law (such as the UNFCCC, the UN-REDD Programme, and the World Bank FCPF) and transnational sites of law (such as the CCBA, the REDD+ SES, Plan Vivo, and Gold Standard). In particular, I would argue that additional research on the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness process in developing countries such as Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mexico, and Vietnam that have moved forward with their efforts to operationalize REDD+ would be especially important.Footnote 976 In addition, as mentioned above, future research on the intersections of REDD+ and rights could also draw on a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods that would allow scholars to explain variations across a larger population of cases. This could enable a rich study of whether and to what extent rights have been recognized and protected in the several hundred REDD+ projects currently being implemented around the world. Finally, additional ethnographic research is required to understand the effects of REDD+ for the rights, livelihoods, systems, and identities of communities at the local level.

A second line of scholarly inquiry could concern the broader structure of the transnational legal process for REDD+. My research confirms that multiple sites, modes, and forms of law have governed the field of REDD+ and that this has led to increasing fragmentation between the legal norms that have been constructed and conveyed for its implementation. Although Bodansky has described REDD+ as an “incipient transnational legal order,”Footnote 977 I have shown that the transnational legal process for REDD+ has led to variegated outcomes across multiple sites and levels of law. It is certainly the case that REDD+ has led to some convergence in the framing of deforestation and forest degradation as issues of concern for climate change and in the emergence of shared understandings that suggest that carbon sequestration should not be prioritized above other important social issues and considerations. On the other hand, law-making for REDD+ has also led to divergent outcomes that are reflected not only in the different ways in which sites of law have addressed these social issues (specifically, as I have shown, in terms of their treatment of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities), but more broadly in the distinct types and scales of REDD+ activities to which they have applied. As such, additional research is needed to examine the structure of the transnational legal process for REDD+ and the opportunities that exist for greater homogeneity and heterogeneity in the development and implementation of legal norms governing different types of REDD+ activities. For instance, I have identified some of the indirect and intersecting pathways through which the design and application of rights-related standards applicable to REDD+ projects may influence and be influenced by national laws and governance arrangements in the forestry and natural resource sectors in developing countries. These pathways could be further explored in relation to additional sites and levels of law as well as additional aspects of REDD+ (such as the legal norms relating to MRV or the development of property rights over carbon).

A third line of scholarly inquiry pertains to the relationship between the multiple transnational legal processes that have been discussed, implicitly or explicitly, in this book. For one thing, one could argue that the origins of the transnational legal process for REDD+ lie in an earlier transnational legal process for CDM. Future scholarship should examine how and what various actors learned from their experience with the construction and conveyance of legal norms for CDM around the world and how this shaped their approach to REDD+. For another, although I have not discussed it as such, this book offers a partial look at the intersections between at least three transnational legal processes, variously focused on the operationalization of REDD+, the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the recognition and protection of the rights of forest-dependent communities. As such, scholars could initiate future inquiries that would begin with the construction and conveyance of the rights of Indigenous Peoples or those relating to forest-dependent communities from the local and national levels to the transnational and international levels and back again, with REDD+ serving as a case study, among others, of the global emergence and spread of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities.

One fourth and final set of questions that should be of interest to scholars has to do with the normative implications of the conveyance and construction of rights as they have come into contact with multiple sites of law in the transnational legal process for REDD+. To be sure, the plurality of processes and manifestations of normativity through which the pursuit of REDD+ has fostered the recognition and protection of rights in developing countries raise important ethical questions. Is there a danger in having transnational legal processes shape legal norms and practices in ways that are indirect, unexpected, informal, and unmoored from the institutions traditionally associated with the sovereign state or established norms of democratic governance within the nation-state?Footnote 978 Should we be more critical of such processes and more attentive to the power disparities that are implicit in their operation?Footnote 979 Or can the exercise of authority through the nonstate and deterritorialized sites of law discussed in this book be “saved” by their appropriation by social movementsFootnote 980 or the practices of global administrative law?Footnote 981 Finally, how should we assess the legitimacy and validity of transnational manifestations of lawFootnote 982 and by what normative principles should the pluralism of legal orders be apprehended and reconciled at a global scale?Footnote 983

Another important ethical quandary concerns the different ways that the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities have been conceived in the context of REDD+. One key issue concerns the modes through which rights to tenure, lands, and resources have been protected in REDD+ policies, programs, and projects. Are efforts to formalize these rights ultimately counterproductive because they undermine the traditional customary rights of communities?Footnote 984 And does the creation of rights to carbon serve the interests of communities or are these rights inconsistent with Indigenous conceptions of nature?Footnote 985 Perhaps the most important matter relates to the recognition of the distinctive status and rights of Indigenous Peoples across multiple sites of law in the transnational legal process for REDD+. The findings in this book force us to consider whether Indigenous Peoples have a special and distinctive claim to an enhanced set of rights due to, as Macklem argues, our need to “mitigate some of the adverse consequences of how the international legal order continues to validate what were morally suspect colonisation projects by imperial powers”?Footnote 986 Are Indigenous Peoples qualitatively different from other marginalized communities that live on or near forests due to their ability to form collective identities based on their special relationship with land?Footnote 987 Or is there something inequitable about providing rights to Indigenous Peoples, but not to other local communities who continue to experience the disabling effects of colonization in other ways and whose lives are also intimately connected to the forests, lands, and resources upon which they depend?Footnote 988 In my view, this challenging set of inquiries probably defies universal answers and instead requires the adoption of a rights-based approach tailored to each particular situation and building on the active engagement, if not leadership, of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 989

The brief research agenda set out above reveals that REDD+ and its complex relationship to rights remains a vital area of scholarly inquiry. In addition to enhancing our understanding of REDD+, future research in this field promises to address difficult questions about the validity and legitimacy of transnational legal phenomena as well as the treatment and empowerment of marginalized groups in the context of environmental law and governance.

Implications for the Study of Transnational Legal Processes

While the primary aim of this book has lain in explaining how and to what effect legal norms relating to human rights were constructed and conveyed in the transnational legal process for REDD+, it also makes five important contributions to the scholarship on the concept of transnational legal processes principally developed by Koh, Shaffer, and Halliday.Footnote 990 First, my book confirms the importance and value of anchoring the study of transnational legal processes in a legal pluralist perspective. By conceiving of law as a plural phenomenon that is not subsumed within a state-centric conception of law, I was able to trace the diverse ways in which legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities were constructed and conveyed through and across multiple sites, modes, and forms of normative ordering. The legal scholarship on REDD+ and rights has adopted a largely positivist approach to law that focuses on state-centric understandings of national and international law, while neglecting other forms, modes, and levels of law that are relevant to understanding the different pathways through which REDD+ activities may affect or address the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 991 By contrast, my approach conceives of law as a plural phenomenon that is not reducible to the formal norms and institutions associated with the stateFootnote 992 and recognizes moreover that law is affected by, and reflected in, the many forms of public and private governance that characterize contemporary transnational relations.Footnote 993 This approach enabled me to study the role and influence of several forms and processes of normativity in the context of REDD+ that might traditionally be excluded as falling outside the scope of law, including those associated with the “soft law” decisions adopted by the UNFCCC, the voluntary project standards set by a certification program like the CCBA, the jurisdictional REDD+ policies adopted by the governments of Indonesia and Tanzania, and the project design documents of local REDD+ projects.Footnote 994

Second, my book illustrates the importance of understanding a transnational legal process as a cycle that moves back and forth between processes of construction and conveyance. By conceiving of legal norms both as “works-in-progress” that actors may develop together within sites of law (construction) and as “fixed entities” whose meaning and effects remain relatively stable as they migrate from one site of law to another (conveyance), I was able to capture the iterative nature of the migration and transformation of legal norms across sites of law. In particular, my in-depth process-tracing of the emergence and evolution of legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+ suggests that the conveyance of exogenous legal norms in a site of law generally triggers the construction of hybrid legal norms at a later stage. As such, this book supports the notion that transnational legal processes tend to engender the translation rather than the transplantation of exogenous legal norms.Footnote 995

Third, this book illustrates the utility of identifying and studying the multiple causal mechanisms that account for the construction and conveyance of legal norms in a transnational legal process. Indeed, my examination of the spread and transformation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities across the UNFCCC, the CCBA, Indonesia, and Tanzania uncovered the role played by a multiplicity of causal mechanisms as well as the significance of interactions between these mechanisms.Footnote 996 By thinking carefully about a range of causal mechanisms and their associate scope conditions, I was able to develop complex causal pathways that could account for the emergence, evolution, and effectiveness of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities across a diversity of sites of law in the transnational legal process for REDD+. In turn, these causal pathways could be used to develop a typology of the causal pathways through which transnational legal processes may unfold, evolve, and exert influence.Footnote 997

Fourth, this book shows that in addition to generating outcomes within particular sites of law, transnational legal processes can give rise to broader structural arrangements, particularly a broader domain of law that is characterized by heterogeneity and competition between sites of law and associated legal norms. At this stage, I have found little evidence of the institutionalization of a new transnational legal order in which legal norms relating to REDD+ or to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities have converged to such a degree that they are taken for granted by actors across sites and levels of law.Footnote 998 Rather, my findings suggest that the transnational legal process for REDD+, at least in its first decade, has engendered more conflict than order between sites of law and related clusters of legal norms.

Fifth, I believe that this book shows the benefits and limitations of process-tracing as a research method for the study of transnational legal processes. The main benefit of process-tracing is that it enables scholars to draw strong inferences about the causal processes and mechanisms that link X and Y in a transnational legal process, which provides an opportunity to capture the complex and evolving nature and effects of legal norms as they move from one site of law to another. This offers the prospects of developing eclectic and multifaceted accounts and theories of the construction and conveyance of legal norms across sites of law. On the other hand, because it requires in-depth and time-intensive qualitative research, process-tracing is not ideal for studying phenomena such as isomorphism, diffusion, and convergence across a wide array of sites of law.Footnote 999 This suggests the utility of a nested research design that would combine both quantitative methods to uncover broad trends in the spread and adoption of legal norms across a population of casesFootnote 1000 and qualitative methods that can trace why, how, and to what effect these legal norms have been conveyed and constructed in a small number of cases. In general, carefully designed empirical research projects like the one presented in this book should become a key priority in the study of transnational legal processes in the years to come.

REDD+ and the Intersections of Human Rights and Environmental Governance

This book has three important implications for global efforts to operationalize REDD+ on the ground. First, my book underscores the potential that a range of instruments and approaches can play in ensuring that REDD+ activities support, rather than infringe upon, the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. Rather than focus on any single instrument, policy-makers should support a range of REDD+ initiatives that create economic and political incentives for respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights, enable multiple actors to engage in deliberative processes to develop shared understandings about the importance of respecting these rights, and empower Indigenous Peoples and local communities so that they are well-positioned to seek the recognition and protection of their rights at the local, national, and international levels. In doing so, policy-makers should not underestimate the important opportunities that are provided by “informal” or “nonbinding” instruments for the construction and conveyance of human rights norms across sites of law. Most importantly, policy-makers should think carefully about the causal logics through which interventions can influence the behavior of relevant actors and how these can complement one another in synergistic ways to engender positive outcomes for REDD+ and human rights.

Second, this book offers new insights on the tensions and synergies between the promotion of community forestry and the global effort to reduce carbon emissions from forest-based sources in developing countries. As is evinced by my case studies of the take-up of community-based approaches to forest governance in the design of jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities in Indonesia and Tanzania, the effectiveness of community forestry as a policy instrument depends largely on the legal, political, economic, and environmental context in which it is implemented. My research in Indonesia suggests that the pursuit of community forestry through REDD+ is unlikely to lead to significant reductions in GHG emissions in landscapes where deforestation is driven by large-scale economic activities that are linked to global supply chains for commodities, such as logging, agriculture, and mining, and where powerful actors stand to lose from the recognition and enforcement of the forest and resource rights of local communities. Solutions to forest loss in these landscapes must instead address the incentives for the unsustainable exploitation of forests that are embedded within global supply chains. Conversely, as is shown by the experience of Tanzania, community forestry may offer a more promising basis upon which to implement a REDD+ policy or project in contexts where the drivers of deforestation are closely connected to the activities of local communities and where it is feasible, both legally and politically, to strengthen and enforce community tenure and authority in and over forests. In other words, whatever merits it may have in terms of advancing the rights and dignity of communities, community forestry should not be seen as a “one-size-fits-all” solution to the complex problems of deforestation and climate change.

A third important practical implication of my research pertains to the governance of the transnational legal process for REDD+. My findings regarding the conveyance and construction of human rights norms in the context of REDD+ activities across Indonesia and Tanzania provide a powerful illustration of the broader politics that have characterized the transnational legal process for REDD+ since 2007. On the whole, I have found that the emergence, spread, and implementation of various types of REDD+ activities have been characterized by the competing ideas, interests, and initiatives of various public and private actors operating at multiple levels. To be sure, this sort of diversity has its advantages in that it may offer opportunities for experimentation and learning that could be used by policy-makers to adjust and calibrate various policy instruments and initiatives for reducing carbon emissions from forest-based sources in developing countries. Yet, too much diversity and competition between transnational actors and legal norms may also hinder the effectiveness of global efforts to support the implementation of REDD+ in developing countries, especially if initiatives overwhelm practitioners in developing countries with additional or incoherent sets of legal norms. In this regard, my research thus points to the need for various actors and institutions to ensure greater complementarity in the construction and conveyance of legal norms for REDD+ across sites and levels of law,Footnote 1001 while at the same time providing scope for continued diversity and mutual learning.Footnote 1002

While focused on REDD+, this ambitious policy agenda ultimately speaks to the broader set of concerns that arise from the relationship between the fields of human rights and environmental governance. At this stage, much of the existing knowledge on the relationship between these two fields has tended to adopt one-dimensional assumptions about the need for environmental policy-making and governance to draw on the language, norms, and machinery of human rights in order to achieve legal, social, and policy change.Footnote 1003 Rather than view human rights as a source of inspiration and change for the environmental field, my book underscores the many ways in which environmental efforts may clash with the protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. However urgent the climate crisis may be, solutions for a low-carbon future should not come at the expense of the rights of marginalized communities that they ultimately seek to serve.Footnote 1004 This view is reflected in the preamble to the Paris Agreement adopted in December 2015, which acknowledges that “Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity.”Footnote 1005

At the same time, my research also provides an opportunity to consider the potential and limitations of seizing the indirect and unanticipated opportunities offered by the mechanisms and processes of transnational environmental governance for the recognition and protection of human rights. The notion that a forest carbon finance mechanism like REDD+ could serve as an opportunity for the conveyance and translation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities had appeared rather unlikely, given the record of rights-related abuses associated with the first generation of public and private carbon sequestration mechanisms implemented in developing countries.Footnote 1006 The fairly positive implications of REDD+ for Indigenous Peoples and local communities reported in this book are all the more surprising since many of the actors who have recognized Indigenous and community rights in the context of REDD+ had been averse to doing so in the past.Footnote 1007 As such, the spread of rights across the domain of REDD+ goes against earlier conventional wisdom that it would have broadly negative repercussions for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 1008 Of course, it is entirely possible that the recognition of these rights is largely symbolic and that their practical implementation remains constrained by existing structural, legal, economic, and political asymmetries. Only time will tell whether or not the gains achieved in the recognition of participatory and resource rights in the context of REDD+ will actually benefit Indigenous peoples and local communities in meaningful ways. As the points of contact between the fields of human rights and environmental governance continue to multiply, it will be increasingly important to think about the complex ways in which these fields may affect one another and to pursue, whenever possible, mutually complementary solutions that can accommodate their central concerns and objectives through innovative policy and advocacy activities.