Even more so than annual vacations, the “final return” to Turkey was expensive. Not only did returning migrants have to finance the moving costs themselves, but they also had to secure housing and find a new job. After years of toiling in West German factories and mines, and wary of Turkey’s high unemployment rate, they generally wished to become their own bosses. But, despite performing their wealth and status, they often struggled to afford the high start-up costs of entrepreneurship. Alongside pooling money from friends and relatives, some sought governmental assistance. In 1976, Hüseyin Şen asked the West German government for a “small loan” of 100,000 DM, explaining that he had purchased a fifteen-acre plot of land that could fit forty cows, and he had already transported five cows and a bull from Germany to Turkey. “If you would give me this opportunity,” Şen promised, “I am ready to leave Germany and return to Turkey forever.”Footnote 1 Levent Mercan, who had spent one of his vacations purchasing an acre for cattle rearing, had a similar request – albeit for far less money.Footnote 2 Nesip Aslan tried his luck in the industrial sector, seeking a loan to build an electrical power plant in rural Hatay.Footnote 3 None of these men, however, received a response. Abandoned in the bureaucratic black hole, they were left to fend for themselves.

Failing to respond, however, did not mean that the Turkish and West German governments were not interested in guest workers’ return migration, nor did it signal a lack of interest in how guest workers spent their money. On the contrary, the connection between return migration and financial investments dominated bilateral discussions at the time. In the early 1970s, as part of a broader effort to determine how to send the Turks home, West German officials attempted to implement a bilateral program that would pay Turkey millions of Deutschmarks in development aid in exchange for assistance in reintegrating returning migrants who were interested in starting their own small businesses in Turkey. At first, the West German government had every reason to believe that Turkey would be amenable to such a program. After all, as Brian J. K. Miller has extensively documented, Turkey initially claimed to welcome the guest workers’ return on the basis that they would bring new knowledge and skills to spark their home country’s internal economic development and modernization.Footnote 4 By the 1970s, however, the Turkish government switched its stance and began opposing guest workers’ return. As West German officials decried in 1984, “The Turkish government wants to avoid everything that could intensify the reverse flow of Turkish citizens.”Footnote 5

The reason for Turkey’s newfound opposition to return migration, as this chapter shows, was primarily financial. Just as the exigencies of global labor markets sparked guest workers’ recruitment to Germany, so too was the tense question of their return enmeshed in economic forces beyond their control. The 1970s, the decade when West Germany first devised policies to promote guest workers’ return migration, marked the highpoint of neoliberalism and the globalization of international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.Footnote 6 Turkey’s relationship to the global economy was volatile, however. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, Turkey’s official policy of import substitution industrialization had yielded steady economic growth, particularly in the nascent manufacturing and industrial sectors that the government prioritized.Footnote 7 But the OPEC oil crisis of 1973 spiraled Turkey into years of unemployment, hyperinflation, parliamentary instability, and political violence.Footnote 8 The government’s excessive borrowing from international institutions and foreign countries exacerbated the problem, ultimately leading to the 1980 military coup. The situation remained dire until the mid-1980s, when democratically elected Prime Minister Turgut Özal, a neoliberal-minded former World Bank employee, overhauled the public sector, privatized firms, and promoted exports.Footnote 9

As part of their broader impact on their home country, guest workers played a significant role in mitigating Turkey’s economic crisis. To repay its foreign debt, Turkey became increasingly dependent on guest workers’ remittance payments in high-performing Deutschmarks, which were far more valuable than the Turkish lira. Among migrants, this was no secret. The renowned Turkish novelist Bekir Yıldız, who had returned to Turkey after a four-year stint as a guest worker in Heidelberg, satirized the home country’s views in his 1974 novel Alman Ekmeği (German Bread):

Give up eating, Ahmets. Give up eating, Jales. Load your stuff on trains, Osmans and Ayşes … Fly home with your marks … Buy land in our big cities … Buy stocks and shares in new factories. When you return, you could become industrialists. What’s wrong with that?Footnote 10

Turkey’s need for investment was so severe, Yıldız insisted, that the Turkish government expected them to put all their Deutschmarks toward farming, industrial production, and the stock market – even if that forced them to “give up eating” in the process. But Yıldız’s satire went further: despite rhetoric promising guest workers the chance of future economic success in Turkey, the Turkish government did not, in fact, want them to return.

To be sure, this dependence on remittances was a pattern that prevailed in many other cases of labor migration across the globe.Footnote 11 But the Turkish-German case stands out because of the timing: the late 1970s, the time when remittance payments became especially crucial, was the very same moment that they starkly declined, since guest workers who had brought their families to Germany had less need to send money home. On the flip side, the Turkish government knew that if guest workers returned to Turkey, the stream of Deutschmarks would dry up even more. This realization, alongside fears of returning guest workers inundating the labor market, made their return a nightmarish prospect. Even when it contradicted guest workers’ best interests, and even when it created bilateral tensions with the West German government, officials in Ankara strove to prevent a mass return migration at all costs.

Although both countries’ governments treated them like pawns on the chessboard of global finance, the migrants strategically navigated the dual pressures from above. They sent remittances home, invested in Turkish industry, and placed their savings in Turkish banks – but they did so on their own terms, when it suited their own wallets rather than Turkey’s federal coffers. And they vocally pushed back against Turkey’s blatant efforts to expropriate their Deutschmarks, with guest workers’ children even initiating an activist movement throughout West Germany to protest the exorbitant cost of paying their way out of Turkey’s mandatory military service in the 1980s. Overall, the knowledge that they were not only unwanted in Germany, but also in Turkey, whose government wanted to prevent them from returning at all costs, widened the rift between the migrants and their home country. Increasingly mistrustful of the Turkish government, the migrants lamented that their home country viewed them not only as “Germanized” Almancı but also as “remittance machines” (döviz makinesi), who posed the least risk and greatest reward to the nation if they kept their physical bodies far away but their Deutschmarks close.Footnote 12 Although they remained tied to the nation, their own government valued them not for their physical presence in their homeland, but rather for the economic benefits reaped on account of their absence.

Development Aid for Return Migration

In the early 1970s, just one decade after initially welcoming Turks as guest workers, the West German government began strategizing about how to send them home. Multiple factors underlay this shift. The economy had vastly improved throughout the 1960s, and, despite guest workers’ significant contributions to Germany’s postwar “economic miracle,” many West Germans praised their own initiative and failed to acknowledge the guest workers’ role. The German population had also restabilized, as rising birthrates helped make up for wartime deaths and alleviated the shortage of able-bodied men. As this new generation of Germans reached adulthood and began entering the labor market in the late 1960s, and as German women increasingly began working outside the home, guest workers were no longer perceived as necessary. Growing condemnation of guest workers “taking the jobs” of Germans – though far less egregious than in the 1980s – both reflected and fueled rising anti-Turkish racism. For West Germany, as for the Turkish government, guest workers represented a financial threat, albeit of a different kind.

West Germany’s evolving solutions to the so-called “Turkish problem,” both in the 1970s and 1980s, rested on one core premise: financial incentives for return migration. Whereas in the 1980s the West German government would directly – and controversially – pay individual guest workers to leave, in the 1970s they initially attempted to work bilaterally with the Turkish government to indirectly incentivize guest workers’ return. Throughout the 1970s, officials at the West German Foreign Office and the Federal Ministry for Economic Development and Cooperation (BMZ) worked tirelessly to convince the Turkish government to cooperate on programs that would promote guest workers’ return under the umbrella of “development aid” (Entwicklungshilfe) to Turkey. West Germany’s basic idea was simple: by improving the Turkish economy through development aid, and by giving jointly administered financial assistance to individual guest workers who wanted to start their own small businesses, they could convince them to leave.Footnote 13 As Matthew Sohm has compellingly argued, tying Turkish return migration to development aid was also part of West Germany’s broader strategy of managing the crises of the 1970s and 1980s by “offloading” perceived domestic problems onto countries in the southern European periphery.Footnote 14

Offering development aid to Turkey served not only the goals of domestic policy, but also its Cold War geopolitical goals. In 1961, the same year as the start of the Turkish-German guest worker program, the West German government had institutionalized its newfound commitment to “Third World” development aid in the establishment of the BMZ. While policymakers genuinely believed in supporting these countries’ “modernization,” they also aimed to jockey for global influence against their East German rival, which had already begun an extensive development aid program the previous decade.Footnote 15 Strategically positioned as a “bridge” between communist Eastern Europe and the oil-rich Middle East, Turkey was especially important to this strategy. Although its 1952 NATO membership aligned it formally with the “First World,” and although Turkey’s accession to the EEC was a realistic possibility, the BMZ’s classification of Turkey as “Third World” reflected West Germans’ core belief – bolstered by their impressions of rural guest workers’ difficulties integrating into West Germany’s modern industrial society – in Turkey’s “backwardness.”

West Germany had been giving Turkey development aid since 1958, but their attempt to tie the funds to guest workers’ return migration began in late 1969, when the BMZ asked the German Confederation of Trade Unions (DGB) to help develop a training program to incentivize guest workers’ return.Footnote 16 The DGB was instrumental to such a program because trade unions, which represented workers of all nationalities in West Germany, were among the key institutions with close formal ties to guest workers. Coordinated by West Germany’s International Federation for Social Work, one of whose board members worked for the DGB, the program solicited guest workers who wished to become mechanics or electricians in Turkey. After completing a twelve-month course, the participants would relocate to Turkey, where they would attend a two-month training course organized by the Turkish government and then search for a job or start their own business. Most enticingly, participants would enjoy a monthly stipend of 150 DM, plus 600 DM if their family returned with them.Footnote 17 But there was a catch: they had to remain in Turkey. Violating their signed “commitment to return” agreement would result in an enormous fine of 20,000 DM.

The program was exclusively oriented toward guest workers from Turkey, not only because they were the largest guest worker nationality, but also because West Germany had strong diplomatic relations with Turkey and assumed that Turkey was still eager to embrace guest workers’ return. As the organizers put it, “in negotiations in Turkey – in comparison to other countries – one can expect the fewest political hindrances.”Footnote 18 This optimism, however, was severely misguided. For over a decade, the Turkish government continually frustrated the BMZ with its refusal to cooperate – even when it contradicted the guest workers’ best interests. As one official noted with dismay, West Germany was apparently striving to “represent the interests of the Turkish guest workers more strongly than their own government.”Footnote 19

Ede Şevki was one of the hundreds of guest workers who applied for the pilot program in 1972. For him, like for many guest workers, the “final return” was not a far-off illusion, but rather a plan that he aimed to put into practice. Hoping to return to Istanbul to open his own auto repair shop, he boldly inquired as to the “exact” amount of money he would receive.Footnote 20 He was also enticed by the program’s colorful Turkish-language advertisements, which depicted men listening to lectures while looking at mathematical equations on a chalkboard, drafting mechanical schematics with protractors, and wearing smart-looking glasses while supervising the factory floor.Footnote 21 The message of professional advancement was simple: joining the program would help them become their own bosses rather than mere peons. Although the translator of Şevki’s Turkish-language application letter was impressed that his vocabulary and grammar were at an “exceptionally high level (for a guest worker),” the program had attracted such a large applicant pool that Şevki was not chosen. In fact, organizers were surprised to encounter over 600 potential applicants, whom they praised as “intelligent,” “eager to learn,” and “goal-oriented.”Footnote 22 Many of the applicants’ interest in West German assistance, they further reported, stemmed from their “deep mistrust of their own government,” which just months before had undergone the 1971 military coup.

Guest workers’ experiences of the training program, however, actually intensified their mistrust of the Turkish government. Soon after its inception, the program began to crumble. By May 1972, fifty participants were enrolled in programs in Nuremberg, Cologne, and Frankfurt.Footnote 23 Yet, with just two weeks before the Nuremberg trainees’ graduation ceremony and scheduled departure for Turkey, details surrounding Turkey’s portion of the training program were still unclear. One West German organizer described the program as “still up in the air,” with “all questions open.” Despite extensive conversations with the Turkish Ministry of Culture and the Turkish Planning Office, he still had no idea “where, when, and how the training courses planned in Turkey would take place.” Turkey, he concluded, had “no interest at all” in the program and, by extension, no interest in assisting returning workers. Rather than ensuring their smooth reintegration into Turkey’s economy, Turkey was treating its own citizens like “guinea pigs.”Footnote 24 As Bundestag Vice President Carlo Schmid complained, “I am very troubled by the thought that this useful program, which was initially off to a good start, could fail at the intractability of several subordinate authorities in Turkey.”Footnote 25 In the words of one German bureaucrat, “These Turks feel that they have been cheated and ditched by the Turkish government.”Footnote 26

Despite these difficulties, the two countries agreed to a broader implementation of the program in the December 7, 1972, Treaty of Ankara. Based on the “friendly relations between both countries and their peoples,” the treaty aimed to “promote economic and social progress in Turkey” by capitalizing on the guest workers’ newly acquired “knowledge and skills.”Footnote 27 Overseen by a joint committee and funded primarily by West Germany, the project operated on what BMZ officials called the “individual support model”: providing funding to the Turkish government, which in turn would support individual returning workers. While this model resembled the pilot program in terms of structure and educational content, it offered increased financial incentives to participants who were interested in starting their own firms in Turkey, including start-up cash, low-interest loans, tax credits, subsidies for materials, and business advice.

The original purpose of the 1972 treaty, as predicated on the individual support model, never materialized. In a 1977 evaluation, BMZ officials complained that Turkey’s failure to follow through with the “unmistakable and detailed provisions” owed not to a lack of funding but to the government’s “deep-seated indifference to promoting return migration.”Footnote 28 Still, this “indifference,” which BMZ officials later sheepishly realized was a vehement “hostility” to return migration, did not impede Turkey from milking the West German government for millions of Deutschmarks in development aid. Through its heavy-handed negotiation skills and opposition to the individual support model, Turkish officials manipulated the flexibility of the 1972 Treaty of Ankara to convince the West German government to redirect funds earmarked for the program toward their main goal: receiving development aid without an influx of returning guest workers.

In negotiations, Turkish economic planners made it clear that supporting the small businesses of individual returning guest workers who dreamt of owning their own farms, opening local grocery stores, or working as taxi drivers was simply not a macroeconomic priority. Instead, they sought to redirect the development aid toward the financing of large infrastructure projects in the energy, transportation, and urban planning sectors.Footnote 29 Specific plans included the construction of the Istanbul subway system and the Atatürk Dam on the Euphrates River, as well as the maintenance of the Bosphorus Bridge connecting the European and Asian sides of Istanbul.Footnote 30 Reflecting the Turkish government’s disconnect from the needs of its citizens abroad, one guest worker complained: “The people say, why a bridge? Instead, they could be building factories so that the people have work … This is a capitalist government that does little for the workers.”Footnote 31

While Turkish officials failed to convince West Germany that supporting major infrastructure projects would indirectly convince guest workers to return, there was one approach upon which the two countries could compromise: the financing of Turkish Workers Collectives (TANGs). Founded on the self-help initiative of groups of guest workers in West Germany, these collectives were joint-stock companies that provided individual guest workers the opportunity to purchase stock in a new firm to be established in Turkey, usually in the agrarian regions from which they came. Guest workers’ primary motivation was financial. They wished to secure a job in anticipation of their eventual return to Turkey, reap income from dividends, and compensate for their inability to finance their own individual large investments by jointly purchasing stocks. But, as Turkish sociologist Faruk Şen revealed in his extensive 1980 study of the Workers Collectives, there was also an emotional motivation: investing in the development of their home communities was a means of making a contribution or giving back (Figure 3.1).Footnote 32

Figure 3.1 A vacationing guest worker in a pristine suit stands in front of straw-roofed houses in his impoverished home village, representing guest workers’ desire to help Turkey’s economic development and modernization, 1970.

The first Workers Collective, Türksan, was founded in December 1966, when a small group of Turkish guest workers living in Cologne gathered in a sports hall and pitched a promising business plan to 2,800 of their colleagues. After pooling their savings, the guest workers would become shareholders in the soon-to-be established industrial firms in Turkey and, upon their return, they would be first in line for jobs. The plan attracted widespread interest. By 1971, thousands of guest workers had invested a total of twenty million DM in Türksan. The company had purchased several plots of land to sell for profit and had opened a wallpaper factory near Istanbul (although, as one West German consular official joked in a pejorative comment on Turkey’s underdevelopment, “Who there needs wallpaper?!”). Türksan also planned several schemes to address guest worker families’ unique needs: a tourism business offering charter flights for vacationing workers, and grocery stores and duty-free shops for Turks abroad.Footnote 33

Reports on Türksan’s success spurred guest workers’ enthusiasm for investing in other collectives. İbrahim Karakaya, who had worked in Bremen for eight years, was intrigued when he received a letter in 1972 from Örgi-Aktiengesellschaft, a Workers Collective in the Central Anatolian province of Nevşehir. The collective planned to open a textile factory in Kalaba, seven miles from his home village, and asked him to contribute some capital. The offer proved enticing, as Karakaya’s prior attempt to start a delivery business in Turkey with a used truck he had bought in Germany had embarrassingly flopped. Eager to make passive income before attempting to establish another potentially unsuccessful business, Karakaya invested 3,000 DM in the collective, paying one-quarter upfront, and he continued to invest more over the years.Footnote 34

While West Germany reluctantly accepted Workers Collectives as the only viable alternative to their prized individual support model, Turkey embraced them. The 1973 platform of Bülent Ecevit’s victorious Republican People’s Party (CHP) named Workers Collectives as part of its new “people’s sector” (halk sektörü) ideology, by which the state would promote economic organization carried out by “individuals and small groups that normally have no possibility to invest.”Footnote 35 In a television interview years later, Ecevit even publicly attributed the inspiration for the concept of the people’s sector to his conversations with guest workers.Footnote 36 To facilitate credit acquisition, in 1975 the Turkish government founded the State Industry and Laborer Investment Bank (DESİYAB), which worked closely with Halk-İş, an organization representing Workers Collectives.Footnote 37 To evaluate and advise the Workers Collectives, the West German government contracted a private consulting firm.

The Workers Collectives proved an economic boon. By 1975, the number of collectives had doubled to fifty-six, comprising a total of nearly 54,000 shareholders abroad.Footnote 38 Within just five years, these numbers quadrupled to 208 collectives and 236,171 shareholders.Footnote 39 By 1980, Workers Collectives had invested around 1.5 million DM in Turkey, established ninety-eight new companies, and created 10,000 jobs, with an estimated additional 20,000 jobs being created indirectly.Footnote 40 In 1979 and 1980, approximately 10 percent of investments in Turkey were carried out by Turkish Workers Collectives, amounting to a total of two million DM since 1972.Footnote 41

Despite preferring the individual support model, the West German government yielded to Turkish pressure due to a genuine belief in the potential for Workers Collectives to fulfill the dual goals of improving the Turkish economy and promoting remigration. A German bureaucrat who traveled to Turkey’s Black Sea region to evaluate eight local Workers Collectives marveled at the “positive effect” on the local economy. Funding the Workers Collectives, he wrote, “currently appears to be the best form of assistance for Turkey.”Footnote 42 In a 1980 report, West German officials announced that creating 20,000 industrial jobs for returning workers would be a “realistic goal.” Although the number of jobs that actually went to returning guest workers “wavers from case to case,” the report took comfort in the observation that the bylaws of the Workers Collectives “generally give priority to members who return to Turkey in job placement.”Footnote 43

This assumption was severely misguided. After pouring a massive 60 million DM into Workers Collectives over the past decade, West Germany learned a startling truth: most guest workers who had purchased stock in the firms were not planning to return to Turkey to work at them.Footnote 44 On the contrary, an extensive 1982 program evaluation revealed that the shareholders had an “irrational” motivation: much like “planting a tree,” they desired only to “symbolically support” their home regions, “precisely because of their permanent absence.”Footnote 45 Even workers who genuinely wished to return were disappointed, as only three out of every hundred jobs went to returning guest workers.Footnote 46 Worse, only 10 percent of the Workers Collectives were successful.Footnote 47 The vast majority suffered from poor planning, inexperienced management, and insufficient capital.Footnote 48 Despite “good intentions,” even the first collective, the celebrated Türksan, had distributed dividends only once in the decade since its founding – and a meager 6 percent at that.Footnote 49

These problems were compounded by the realization that the BMZ’s definition of a Workers Collective was so lax that it permitted private Turkish businesspeople, who had not migrated to Germany, to exploit West German development aid. Given that only a majority of shareholders needed to be guest workers living in West Germany, Turkish businesspeople found a loophole: they could establish a private firm and retain a 49 percent ownership share and, as long as the remaining 51 percent was held by Turks abroad, they could receive the subsidies and benefits of being classified as a Workers Collective.Footnote 50 Firms sponsored by private Turkish businesspeople had no incentive to employ guest workers seeking to return. Some, like the textile firm Meric-Textilen-Aktiengesellschaft in Edirne, even expressed reluctance to hire its own shareholders. Instead, the firm believed that returning guest workers, who had become accustomed to the higher income and social services in West Germany, would not be willing to accept the minimum wage typically paid to local agricultural workers (in 1980, 3,300 TL or 236 DM).Footnote 51

Even amid these revelations, Turkey continued to exploit West German naiveté. Desperate to maintain the flow of Deutschmarks, Prime Minister Ecevit jumped to the Workers Collectives’ defense: “Whatever has been achieved is the accomplishment of the Turkish worker,” and “whatever mistakes have been committed are the fault of others!”Footnote 52 When West Germany tried to return to the individual support model throughout the 1980s, Turkish officials’ reactions were “not especially encouraging.”Footnote 53 The final result was bleak. By 1988, sixteen years after signing the Treaty of Ankara and envisioning a large-scale training program to promote return migration through the individual support model, the West German government had distributed only four hundred loans directly to returning guest workers and a mere five hundred had participated in a training program.Footnote 54 Although West Germany had succeeded in assisting the Turkish economy, it had failed in its primary goal of convincing guest workers to leave, and was thus wasting its money.Footnote 55 As the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung put it, this “quite excellent idea” turned out to be a “flop.”Footnote 56

Money, Manipulation, Mistrust

If the Turkish government sought to portray itself as the caretaker of its citizens abroad, then why did it vehemently oppose programs that would help them realize their dreams of returning to Turkey and starting their own businesses? One important reason was Turkish economic planners’ conviction that funneling West German development aid into Workers Collectives would be far more lucrative than helping individual guest workers with what they regarded as frivolous ventures, such as buying a couple dozen cows, opening a bakery, or starting a taxi business. Yet supporting the Workers Collectives did not necessarily preclude entertaining the possibility of West Germany’s individual support model. Pursuing both options simultaneously, moreover, would have helped far more guest workers than it did. The real reason cut much deeper: fundamentally, for financial reasons, the Turkish government did not want the guest workers to return.

Since the 1961 start of the guest worker program, the Turkish government made no secret that guest workers were crucial to its economy. Turkey’s 1963–1967 development plan touted the program for mitigating unemployment by “exporting surplus labor.”Footnote 57 But in 1973, the bubble burst. Fearing its own rise in unemployment amid the OPEC oil crisis, West Germany abruptly ceased all new guest worker recruitment. The recruitment stop proved devastating not only to hundreds of thousands of Turks, many of whom were literally standing in line at recruitment offices at the time of the announcement, but also to the Turkish government. In the months before the recruitment stop, a BMZ official involved in the development aid negotiations called it “urgently necessary” to warn the Turkish government of the harsh reality: West Germany “cannot permanently solve the Turkish unemployment problem.”Footnote 58

Unable to export additional labor to Germany, the Turkish government desperately hoped that the guest workers who were already there would stay put. During a 1974 visit to Bonn, Turkish Ambassador Vahit Halefoğlu expressed “fears of a mass remigration,” as unemployment was expected to double by 1987, compounded by an estimated population growth from 37.5 to 55 million.Footnote 59 A decade later, following a bilateral development aid meeting in 1983, BMZ officials reported that “there is a general fear here that the dam against remigration could break” – even “if one makes exceptions.”Footnote 60 Returning guest workers, the Turkish government further insisted, “expect too high a salary” and “return to such provinces where no need for their labor exists.” Such statements revealed a lack of confidence in the guest workers. Skeptical that even the best-laid and best-financed plans to start small businesses would ever materialize, Turkish officials categorically assumed that returning guest workers would reenter the labor market. Their own government viewed them as destined to fail and, in this way, helped perpetuate their failure.Footnote 61

Even more worrisome than unemployment was the prospect that a mass remigration would lead to a decline in remittance payments, which were crucial not only to guest workers’ families but also to the Turkish economy. Like exporting surplus labor, remittances had been a crucial part of Turkey’s various Five-Year Development Plans. The 1968–1972 plan affirmed the need to redirect remittances toward investments in productive sectors,Footnote 62 the 1973–1977 plan praised remittances as the “most important” factor allowing the country to repay its foreign debt,Footnote 63 and the 1979–1983 plan expressed the need for greater state control over remittances and to direct them “rationally” to the National Treasury and State Economic Enterprises.Footnote 64 The growing reliance on remittances reflected that they were among the few sources of foreign currency at a time of limited exports and foreign debt.Footnote 65 In short, explained Cumhuriyet in 1971, Turkey viewed the guest workers as “hens that lay golden eggs,” whose key duty was to “fill the vaults of the Central Bank.”Footnote 66

As early as the 1960s, the Turkish government enacted measures to facilitate the transfer of guest workers’ Deutschmarks. The Turkish Postal Service prepared bilingual remittance forms, and the government detailed the step-by-step process in advice books printed for workers living abroad.Footnote 67 To ensure that guest workers’ money yielded interest for the government, a 1973 advice book cautioned guest workers against sending cash home in envelopes – a crime that, if caught, could lead to federal prosecution.Footnote 68 While guest workers seeking to transfer money by mail could fill out a handwritten remittance form at a German post office, the advice book warned them about numerous problems, such as having insufficient language skills to handwrite the sum in German, and that transferring sums larger than 1,300 DM required two forms. The best option, the advice book counseled, was to use the special postal checks offered by Turkish banks, as the German employees representing the banks could help fill out the forms. Efforts to direct guest workers’ remittances through formal channels thus tightened the two countries’ institutional relationships.

Filling out remittance forms was a central part of guest workers’ everyday lives, and Turks sent more money home on a regular basis than other guest worker nationalities (Figure 3.2).Footnote 69 Murad, whose father opened a tailor shop in Witten after spending several years as a guest worker, marveled at the number of guest workers who visited the tailor shop daily not to have their pants hemmed or suits taken in, but rather to fill out paperwork. Although Murad did not fully understand the process as a child, his father told him that the pieces of paper featuring colorful pictures of Turkish landmarks that he stored behind the counter were remittance forms (havale deftleri). Often with assistance from Murad’s father, who could speak both Turkish and German and was thus in a relatively privileged position, the guest workers filled out the forms, indicating the number of Deutschmarks to transfer, the recipient’s name, and the bank branch in Turkey where the money would be picked up. The guest workers then took the forms to a German bank or a Turkish bank with branches in Germany, basing their decisions on the lowest transaction fees.Footnote 70

Figure 3.2 Guest workers send remittances at Türkiye Halk Bankası, one of the many Turkish banks with branches in West Germany, ca. 1970.

The Turkish government also developed schemes to incentivize guest workers to deposit their Deutschmarks in savings accounts at Turkish banks. With the introduction of convertible Turkish lira deposits (CTLDs) in 1967, guest workers could open special accounts in Turkish commercial banks at an interest rate that was 1.75 percent higher than the Euromarket rate. Sweetening the deal, the publicly owned Turkish Republican Central Bank guaranteed the principal and interest against the risk of a potential lira devaluation. The Turkish government, too, benefitted from the CTLDs, which constituted short-term loans in Deutschmarks. In terms of process, the commercial banks transferred guest workers’ deposited Deutschmarks directly to the Turkish Central Bank, which returned the adjusted sum in lira and further loaned the Deutschmarks to state-owned enterprises for the financing of imports, long-term investment projects, and the repayment of foreign debt. In 1975, luxuriating in the massive influx of foreign currency, the Turkish government extended the opportunity to hold CTLDs to all nonresidents, including foreign corporations.Footnote 71

As part of the CTLD scheme, the Turkish government also sought out a West German partnership. In a 1976 agreement between the Turkish Central Bank and West Germany’s Dresdner Bank, the Turkish government offered up to an additional 1 percent in interest for guest workers who opened convertible accounts at Dresdner Bank, which would then transfer the Deutschmarks to the Turkish Central Bank in exchange for lira.Footnote 72 The two banks, cooperating with West Berlin’s Bank for Trade and Industry, advertised their joint services to guest workers in a colorful pamphlet featuring the bold Turkish text “How to Open a Foreign Savings Account” over a backdrop of alternating lira and Deutschmark bills.Footnote 73 The back cover provided examples in both languages to assist customers in voicing their requests for transfers, withdrawals, and deposits. In another pamphlet, the Turkish Central Bank boasted about its advantageous exchange rate due to its partnerships and cautioned workers to avoid trading money on the black market. Appealing to the guest workers’ nostalgia and nationalism, the pamphlet suggested that investing would offer “endless possibilities, both for you and for your country.”Footnote 74

The Dresdner Bank partnership notwithstanding, West German and Turkish banks typically engaged in fierce competition for guest workers’ Deutschmarks. In one ethno-marketing advertisement, the West German bank Sparkasse boasted in Turkish that “Every Sparkasse is ready to help you” (Figure 3.3).Footnote 75 Yet West German banks could hardly compete: a survey of guest workers in Duisburg revealed that 83.5 percent of their deposits were in Turkish banks, and only 13.5 percent in German ones.Footnote 76 Turkish banks’ success lay partially in their savvy appeals to guest workers’ nostalgia for their homeland and separation from their loved ones. Yapı ve Kredi Bankası distributed an advertisement depicting a guest worker family in their living room with a framed photo of a faraway relative hanging on the wall, captioned: “When exchanging currency or sending remittances, the savings account you have opened at Yapı Kredi guarantees high returns for the relatives you have left behind in the homeland.”Footnote 77 Türkiye İş Bankası appealed to Turkish nationalism, insisting that its financial advisors were not only “friendly people eager to answer your questions” but also, most importantly, “your own people who speak your own language.”Footnote 78

Figure 3.3 The West German bank Sparkasse courted Turkish clients with a Turkish-language ethno-marketing advertisement stating, “Every Sparkasse is ready to help you,” ca. 1980.

Not only banks but also consumer goods corporations courted guest workers’ Deutschmarks through nationalist appeals. This trend was particularly pronounced in the cigarette market. An advertisement for the Turkish cigarette brand Topkapı, targeting guest workers, depicted a cartoon cigarette box with a speech bubble uttering Atatürk’s famous assertion, “How happy I am to be a Turk.” The accompanying text reported that Turks in West Germany spent 500 million DM annually on cigarettes and argued that, if they gave this to Topkapı instead of foreign companies, then they would “support the development of our homeland.”Footnote 79 Even non-Turkish companies pursued this strategy. A competing advertisement for the American cigarette company Camel touted the tobacco’s Turkish origin. Because Camel’s tobacco was cultivated in Izmir and was a “Turkish and American blend,” even this US-based company could be considered “part of the homeland.”Footnote 80

The push to court guest workers’ Deutschmarks did not always work. Strategically navigating the competing options, guest workers made their investment and purchasing decisions based on their and their families’ consumer preferences and financial interests rather than on nationalist rhetoric. To diversify their portfolios and take advantage of offers of high interest rates, many deposited their savings in multiple banks. One guest worker in Dortmund, Osman Gürlük, divided the minimal savings from his low monthly salary of 1,200 DM between three Turkish and West German banks – one in Istanbul and two in Dortmund – and boasted that he had saved 5,000 DM in three years, not including the remittances he sent to his wife and child in Turkey.Footnote 81 Guest workers’ financial prioritization of family over nation became especially apparent amid the rise in family migration of the 1970s. As they increasingly brought their spouses and children to West Germany and began to settle there more permanently, they had less need to send money home. Simultaneously, the economic downturn and rising unemployment after the 1973 OPEC oil crisis left many guest workers strapped for cash and unable to deposit as much into Turkish banks.

These factors, alongside West Germany’s decision to stop recruiting guest workers in 1973, led to a stark decline in remittances during the 1970s. The percentage of guest workers who regularly sent money to Turkey declined from two-thirds in 1971 to just 43 percent in 1980.Footnote 82 Between 1965 and 1974, the total amount of money guest workers sent to Turkey had quadrupled to 4.6 billion USD.Footnote 83 But abruptly, the annual remittance sum plummeted by nearly one-third, from 1.4 billion USD in 1974 to just 980 million USD in 1976, and hovered there through 1978. Remittances temporarily recovered in the first half of 1979 due to the 44 percent devaluation of the lira and a brief return to confidence in investment, but they declined again later that year due to continued political and economic instability. Not until the 1980s, when the economy began to recover following the postcoup neoliberal economic overhaul, did remittances return to a steady rate.

The nosedive in remittances had serious consequences (Figure 3.4). Not only did the decline cost Turkey 1.7 percent of its Gross National Product (GNP) for 1974–1976, but it also exacerbated the country’s foreign debt crisis amid the international oil shocks of the 1970s. Between 1973 and 1977, the same period as the decline in remittances, Turkey’s foreign debt jumped from 3 billion USD to 11 billion USD, accounting for a rise from 8 percent to 23 percent of the country’s GNP.Footnote 84 The political instability and repeated changing of governments throughout the 1970s – coupled with policymakers’ refusal to reform their failing economic policies – made Turkey highly susceptible to global recessions and price fluctuations, and the Turkish Central Bank’s excessive short-term borrowing through guest workers’ CTLDs contributed markedly to the accumulation of debt. Of all the debtor countries, Turkey’s situation was particularly dire: Turkey alone held 69 percent of the total debt among the developing countries that worked with the IMF and the World Bank to reschedule their foreign payment obligations and to implement structural adjustment and austerity programs between 1978 and 1980.Footnote 86 Although Turkey’s foreign debt as percentage of GNP continued to rise throughout the 1980s, the growth reflects the five Structural Adjustment Loans granted by the World Bank and the IMF from 1980 to 1984, which had an overall stabilizing effect on the Turkish economy.Footnote 87

Figure 3.4 Significance of guest workers’ remittances to the Turkish economy. Examining the 1976–1978 period in particular reveals that the stark decline in remittances exacerbated Turkey’s economic crisis by coinciding with a detrimental rise in external debt, inflation, and unemployment. Graph created by author.Footnote 85

But for ordinary individuals living in the throes of the 1977–1979 debt crisis, the economic recovery of the 1980s was difficult to imagine, and any optimism was overshadowed by the turmoil they confronted in their everyday lives. By 1980, inflation had skyrocketed to over 90 percent, leading to a 250 percent increase in the price of oil.Footnote 88 Policymakers hurriedly implemented austerity measures in January through a 30 percent devaluation of the lira and a prioritization of exports over internal consumption. Still, the winter months proved especially harsh. Individuals and families who were unable to afford oil and coal endured freezing, unheated homes.Footnote 89 They likewise struggled to afford everyday commodities like sugar, coffee, cigarettes, and alcohol.Footnote 90 This misery exacerbated the ongoing political unrest that motivated the 1980 military coup.

Aware that guest workers’ declining remittances were aggravating the debt crisis, observers who had not migrated, particularly in the Turkish media and government, began openly criticizing guest workers’ spending habits. Among the most vocal was Milliyet columnist Örsan Öymen, who had lived in West Germany while working as an editor at Westdeutscher Rundfunk. In a provocative column, Öymen blamed Turkey’s woes on the guest workers’ selfish refusal to send remittances. Remittances, he argued, were guest workers’ civic duty – their means of giving back to their homeland in exchange for their special privileges, such as the ability to import certain goods duty-free. To boost remittances, and to help Turkey escape the “yoke of foreign financial capital institutions,” Öymen proposed a law that would force guest workers to remit a mandatory sum set by the Turkish government. By his calculation, if each guest worker transferred 20 DM daily in remittances to their families or bank accounts in Turkey, that would amount to 7.2 billion DM or 4 billion USD annually. “Is it not the state’s right to demand a sacrifice from these workers, such as sending remittances to their country?” he inquired. “Why would that be unfair?”Footnote 91

Incensed by Öymen’s column, guest workers flooded his mailbox with a storm of angry letters and derided him as an “intellectual” who was out of touch with their problems.Footnote 92 At fault were not the guest workers themselves, one insisted, but rather the corrupt and profiteering Turkish banks, which “think of nothing other than snatching the marks from the workers’ hands.” The most outrage, however, was directed at the Turkish government, which had spent the remittances “irresponsibly” through failed import–export policies and had not offered an exchange rate that was competitive with the black market, where it was possible to get a 50 percent return on the sale of Deutschmarks. Without referencing the bilateral development aid negotiations directly, another man questioned why the Turkish government had refused to provide loans to individual guest workers who wanted to invest in Turkey or had encountered financial problems. The government’s seeming apathy or hostility toward its citizens’ needs was all the worse, one man wrote, because “we are masses of patriotic workers,” who have “contributed to the country’s development” by “pouring out sweat” and “scavenging European countries’ waste and trash off the streets.”

Amid this outcry, the Turkish government made no secret of its economically based opposition to return migration. In April 1982, Der Tagesspiegel reported that after four days of intensive talks with Turkish Foreign Minister İlter Türkmen and Prime Minister Bülent Ulusu, West Berlin Mayor Richard von Weizsäcker “now understands better than before that Turkey, amid its economic situation and high native unemployment, cannot be interested in a large wave of remigration.”Footnote 93 Several months later, the Turkish tabloid Güneş ran a front-page article reporting the guest workers’ concerns that their countrymen would be hostile to their return. The migrants had learned of the Turkish population’s fears that they would overburden the labor market and “evaporate any hopes that those currently unemployed would ever find a job.”Footnote 94 A Der Spiegel article exposed the central tension clearly: while the Turkish government “appears” to harbor a “humane concern for the fate of their countrymen,” they are primarily concerned with “tangible economic interests” and a mass remigration would “plague” the country.Footnote 95

The association between the guest workers’ remittances and the Turkish government’s disinterest in their return was clearest during a tense January 1983 meeting in the northwestern Turkish city of Bolu, where representatives of several local Turkish Workers Collectives, Turkey’s DESİYAB Bank, and West German and Turkish government officials met to discuss how guest workers’ savings could be used to finance the development of the Turkish economy.Footnote 96 The Turkish newspaper Hürriyet reported that these tensions came to a head in a contentious “duel of words” between West German State Secretary Siegfried Lengl of the BMZ and Turkish Finance Minister Adnan Başer Kafaoğlu. When Lengl began to plea for Turkish understanding of West Germany’s labor market concerns and the urgent need for workers to return to their home country, Kafaoğlu abandoned his prepared speech and firmly underscored the significance of guest worker remittance payments to the Turkish national economy. “Turkey needs the workers’ remittances for many years to come,” the newspaper paraphrased, “and she will not pull back her workers.”Footnote 97

The realization that the Turkish government prioritized guest workers’ Deutschmarks over their own well-being soured the migrants’ impression of their homeland. Saim Çetinbaş, a former guest worker who had opened a Turkish grocery store in West Berlin, explained how he had repeatedly sought to heed the call for investment but had received no official assistance and only trouble from the Turkish government. The most devastating of his many failed business ventures involved a pickle factory that he opened from West Germany on a 22,000 square-meter plot of land in Çerkezköy. After he closed the factory at a loss of 2 million DM, the municipal government apparently seized the rest of the land with no notice and no recompense. Rather than “thanking” him for investing his Deutschmarks, the government “always makes things more difficult,” he complained. His scorn, however, extended to the Turkish population as a whole: “In the eyes of Turkey, we are all viewed as marks. No one thinks about us as having flesh and blood.” Outraged, Çetinbaş swore never to permanently return to Turkey. For him, it was only a “beautiful vacation country,” where his children happily sunbathed along the Mediterranean Sea each summer. As for any deeper connection to Turkey, “I don’t think about those who don’t think about me.”Footnote 98

This mistrust and sense of betrayal went much further, however, and became a core component of the way that guest workers viewed their changing relationship to Turkey. A 1983 study conducted by the University of Ankara and the University of Duisburg–Essen revealed that a startling 90 percent of Turkish guest workers in West Germany believed that the Turkish government viewed them only as sources of remittances.Footnote 99 İsmail Akar, who had worked in Germany from 1963 to 1980, encapsulated this sentiment in a scathing interview with Milliyet: “If you ask me, the first priority of past politicians was to abandon our workers in Germany like a burdensome, barren herd. They view us as remittance machines.”Footnote 100 By viewing the guest workers so starkly in economic terms – not just as laborers, but as machines churning out Deutschmarks – Turkey stripped guest workers of their humanity and relegated their wishes to the backburner. Although West Germany also viewed guest workers in economic terms, the pain stung worse when it came from a faraway homeland to which many guest workers yearned to return.

Serve in the Military – Or Pay

The Turkish government also exploited the Deutschmarks of guest workers’ children by providing the option for military-age youths living in West Germany to serve only two rather than twenty months of mandatory military service. This “military service by payment” (bedelli askerlik), as it was called, came with a catch: a price of 20,000 DM. This hefty sum, over six months of wages for the average Turkish migrant, was an impossibility for the up to 400,000 young men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-two affected by the policy. Facing the prospect of losing their jobs after long absences, they resorted to desperate measures to come up with the money. By the mid-1980s, the notion that the Turkish government was maliciously exploiting its young countrymen’s Deutschmarks prompted a wave of grassroots activism, attracting the support of sympathetic West German observers eager to criticize the Turkish government.

Mandatory military service in Turkey had a long history. The 1927 Military Law, passed just four years after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Turkish Republic, applied not only to able-bodied men born in Turkey but also, explicitly, to “immigrants” and “foreigners” who had Turkish citizenship, even if they lived abroad. Because those between twenty and forty-one years of age were subject to an eighteen-month basic training and draft lottery, the law posed a particular conundrum for guest workers, many of whom had migrated to Germany at precisely that age and who, due to unscrupulous employers eager to fire Turks, encountered difficulties returning to Turkey without losing their jobs. The law also affected guest workers’ children born in Turkey but brought to Germany, who reached adulthood abroad. To remedy the situation, the Turkish government amended the law in 1976. Whereas citizens living in Turkey could postpone their military service for only two years, those living abroad could petition the consulate for postponement every two years until age thirty-eight.Footnote 101

In 1979, at the height of Turkey’s foreign currency crisis, the Turkish government revised the Military Law to permit citizens abroad to pay their way into a shortened two-month military service. As so often with Turkish policies toward the migrants abroad, the goal was primarily financial. Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit’s major announcement of the draft amendment came in a speech on plans to strengthen the economy and to “make use of” guest workers’ remittances, while Defense Minister Neşet Akmandor publicly explained that the policy would be the “most efficient and effective use of a large and important resource.”Footnote 102 Reflecting the policy’s orientation particularly toward Turks in West Germany, the revised Military Law explicitly cast the sum not in lira but in “Deutschmarks or the equivalent in other currencies.” While Ecevit set the price at 5,000 DM, the amendment, as passed the next year under the new prime minister, Süleyman Demirel, reduced the period of service to one month and doubled the price to 10,000 DM.

The price abruptly doubled again to 20,000 DM following Turkey’s 1980 military coup, when the authoritarian government ushered in an era of increased societal militarization and attacked the economic crisis by decree. By January 1982, Turkey had pocketed an impressive 2.4 billion lira in military exemption fees, the vast majority of which went to the Defense Ministry budget.Footnote 103 A few years later, this number climbed to 500 million DM – a “welcome injection of cash,” marveled one West German newspaper, considering that Turkey had over 30 billion USD in foreign debt.Footnote 104

Always eager to report on guest workers’ relationships to their home countries, and to portray the Turkish government negatively, the West German media expressed a curious fascination with the topic of “guest workers in uniform.” Repeatedly, journalists emphasized that the exorbitant 20,000 DM price tag reflected not only the postcoup authoritarianism and militarization of Turkish society but also the government’s desire to exploit the workers’ Deutschmarks. Compared to other guest worker nationalities, this assessment rang true. By the 1980s, military-age Greek citizens living abroad could pay between 500 and 1,000 DM for an exemption, Portuguese men could pay a meager 90 DM, and Italians and Spaniards enjoyed exemptions free of charge. Only Yugoslavs faced harsher restrictions than Turks, as the outright lack of exemptions meant that they had to return to Yugoslavia for a fifteen-month period of service.Footnote 105

Still, even paying the 20,000 DM did not free guest workers from conflicts with their employers, which became matters of dispute in West German courts. Amid unemployment and rising anti-Turkish racism, even a two-month absence for a shortened military service could cost a Turkish worker his job, or at least several months of wages. While West Germany’s 1957 Law for Job Protection in Case of Conscription guaranteed that workers would not be terminated from their jobs during their military service, the law did not apply to guest workers.Footnote 106 In 1981, a thirty-two-year-old Turkish guest worker successfully sued the Krupp steel factory for refusing to grant him unpaid vacation for his military service (thereby firing him) and won 4,000 DM in wages.Footnote 107 Others lost their cases. Several months later, a Regional Labor Court in Hamm ruled against a guest worker in a similar situation, determining that the employer had not violated his “duty of care.”Footnote 108

The judicial ambivalence was finally settled in September 1983, when the Federal Labor Court in Kassel ruled that “German employers must grant leave to and later reemploy Turkish citizens for the length of the shortened mandatory military service in Turkey.”Footnote 109 This victory, however, was limited. Privileging wealthier guest workers, the protection applied only to those who had enough money to finance the 20,000 DM for a shortened military service, meaning that employers could still legally fire guest workers whose inability to pay the sum required them to complete the full eighteen months. As Mete Atsu, a Turkish board member of the German Confederation of Trade Unions, complained, “What employer is voluntarily willing to keep a job open for a Turk for eighteen months?”Footnote 110 This discrepancy was especially troubling to guest workers’ children, who, upon reaching adulthood and entering the job market, were not only lower-paid but also dispensable. “Normally, twenty- to thirty-year-olds would be establishing their livelihoods,” noted a Turkish social worker. “Now they have to give the money to the state.”Footnote 111

Horror stories of the harsh conditions in the postcoup Turkish military, widely reported in the West German media, intensified the need to scramble together the 20,000 DM. An exposé in Vorwärts, the Social Democratic Party’s official newspaper, publicized the miserable experience of Ramazan Türkoğlu, a telecommunications worker in Cologne who had returned from his two-month basic training in Burdur: he and the other eighty recruits were forced to sleep in a small and poorly ventilated room, he had observed a corporal brutally beating a recruit, and rumor had it that the food was laced with medications to suppress their libidos.Footnote 112 For regime opponents, the sheer prospect of returning to Turkey posed a threat. Hamza Sinanoğlu, who had lobbied on behalf of Kurdish asylum seekers in West Germany, was detained for a week immediately upon arriving in Turkey for his military service. Sahabedin Buz was tortured for five months after the military courts accused him of reading the IG Metall trade union newspaper and collaborating with communists.Footnote 113

With these dual anxieties of losing their jobs and subjecting themselves to the harsh conditions in Turkey, many military-age youths scrambled to pay their way out of military service by any means necessary – even if they could not afford the 20,000 DM. For those who had become self-sufficient, one option was to sell their businesses. One man living in Bockenheim placed a personal advertisement in the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet, announcing his intent to sell his specialty Balkan grocery store in West Germany to make “the money necessary for my military service,” while another sought to sell his tailor shop “urgently” for the same reason.Footnote 114 Given that most military-age youths were wage laborers, however, a more common option was to turn to their parents for financial assistance. But even if their parents had worked in Germany for two decades, they could often not afford the 20,000 DM price tag and, even if they could, they planned to use it toward their dream of returning to Turkey. The burden on parents’ wallets was especially difficult for families with multiple children. A family with four sons, for example, would be required to come up with 80,000 DM – an impossibility for the vast majority of parents. Parents were thus forced to choose which of their children they would assist, if any.

Absent financial assistance from their parents, many young men attempted to finance the 20,000 DM by taking out loans. Going through formal channels, however, proved difficult. Wary of taking risks on Turkish youths they deemed likely to lose their jobs and thus default on their loans, West German banks generally granted a maximum of 6,000 DM.Footnote 115 The banks also required loan-seeking Turkish customers to provide financial guarantees (Bürgschaften) from two other individuals, one of whom had to be German.Footnote 116 To circumvent these hindrances, many men resorted to taking loans from wealthy private individuals, “dubious money-lenders,” and “loan sharks,” all of whom charged exorbitant interest rates.Footnote 117 West German journalists emphasized that the pressure to repay the loans forced the young men into money-making criminal activities such as the illicit drug trade – an assessment reflecting longstanding tropes about Turkish men’s criminality.Footnote 118 In one sensationalist article, Hürriyet reported the case of a twenty-eight-year-old migrant in Bielefeld who was allegedly murdered by a family member for demanding that his father-in-law repay a 20,000 DM loan so that he could use it to pay his way out of military service.Footnote 119

Those who simply ignored their military conscription faced harsh long-term consequences. Under Turkey’s 1930 Law on Absentee Conscripts and Draft Evaders, even a one-day delay in arrival to military service during peacetime could result in imprisonment of up to one month.Footnote 120 And given that Turkey, unlike West Germany, did not recognize conscientious objection, saving face by claiming to oppose military service on moral or religious grounds was not an option. One young man who decided not to report to basic training told the Rheinische Post that he had come to deeply regret the decision. The Turkish consulate had refused to renew his passport and was threatening to revoke his Turkish citizenship altogether. As a “stateless person” without a passport, he would face deportation to Turkey, where he would surely be imprisoned for draft evasion.Footnote 121

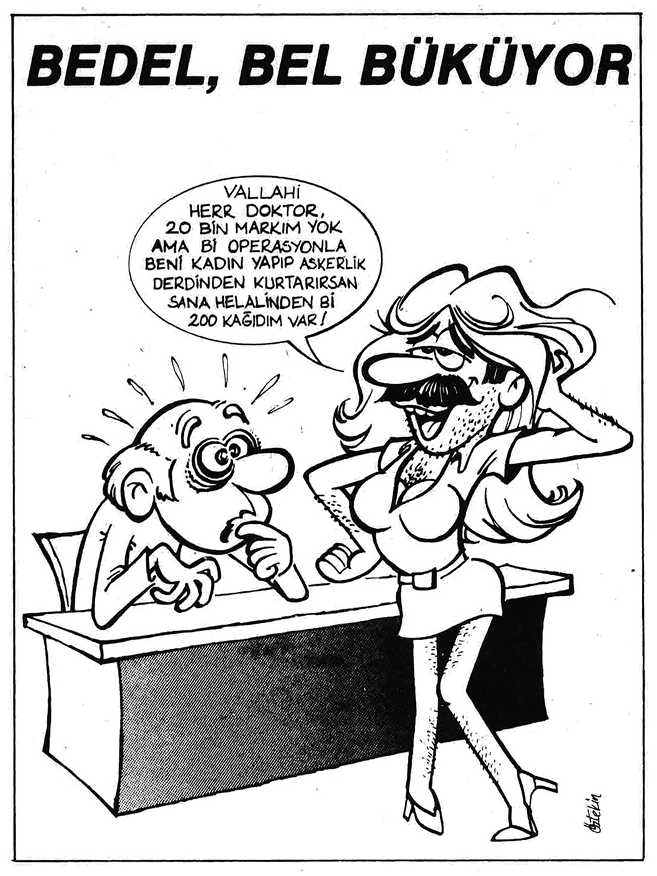

Feeling exploited not only by the loan sharks but also by the Turkish government, young Turkish men living in West Germany spoke out against the 20,000 DM and banded together in activism. In March 1984, discussions in schools, coffee houses, and workplaces consolidated into a formal protest movement with the establishment of the Federal Initiative of Military-Age Youth from Turkey (FEBAG). The grassroots organization, run by military-age youths themselves, initiated a letter-writing campaign to the Turkish government demanding a reduction of the price to a more manageable 5,000 DM.Footnote 122 With initial branches in the Ruhr cities of Bochum, Gelsenkirchen, and Herne, FEBAG quickly spread to nearly one hundred West German cities, where its members staged well-attended demonstrations featuring Turkish food and recreational activities like soccer tournaments and breakdancing. The organization also distributed a Turkish-language newsletter called Bedel, which alongside well-argued articles about the cause also contained effective cartoons, such as a drawing of a man being crushed by the weight of a 20,000 DM money bag. In another particularly striking cartoon, a man dressed in women’s clothing begs a German doctor for help: “By God, Herr Doctor, I don’t have 20,000 marks, but I do have 200 bucks for you if you’ll do an operation to make me a woman and save me from military service” (Figure 3.5). This strategy paid off: the FEBAG activists collected the signatures of 20,000 young men and their fathers, who in many cases would be the ones shelling out the money.

Figure 3.5 FEBAG activists published a humorous cartoon in their newsletter, conveying the desperation that young migrants felt when trying to pay their way out of military service, 1984. The caption reads: “By God, Herr Doctor, I don’t have 20,000 marks, but I do have 200 bucks for you if you’ll do an operation to make me a woman and save me from military service.”

While the struggle surrounding military service affected Turkish men living in West Germany, FEBAG connected its activism fundamentally to the question of return migration. Not only did the activists argue that paying the 20,000 DM would be a waste of money that they might have otherwise spent toward the costs of remigrating to Turkey, but they also condemned the government’s overall failure to create jobs and training opportunities for individuals who wished to return. “What has been done with the 500 million marks we have sent?” the activists questioned, chastising the Turkish government for using their remittances for the defense budget rather than the “development of the homeland.”Footnote 123 Although Defense Minister Zeki Yavuztürk attempted to stifle these concerns by insisting that military-age youths who paid the 20,000 DM were “performing a national service,” the activists saw through the rhetoric and continued to emphasize the Turkish government’s failure to address the difficulties faced by return migrants.Footnote 124 As one young man who had grown up in West Germany and now faced unemployment explained, “I need the money to return to Turkey” but “I have no chance of finding a job in Turkey either.”Footnote 125

Soon, FEBAG’s platform not only spread to Turkish migrants in the Netherlands but also attracted the support of important stakeholders throughout West Germany and Turkey. FEBAG’s allies tended to be left or center-left organizations that generally supported Turkish migrants: the German Confederation of Trade Unions (DGB), the metalworkers’ trade union IG Metall, and the Protestant churches. Individuals with similar political inclinations also supported FEBAG, including select Social Democratic and Green Party parliamentarians and Liselotte Funcke, the Federal Commissioner for the Integration of Foreigners. FEBAG’s cause also resonated with Turkey’s Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions (Türk-İş), as well as organizations founded by Turkish migrants in West Germany, such as the Federation of Workers Associations (FİDEF), the Federation of Progressive People’s Associations in Europe (HDF), and the Turkish Youth Association in West Berlin.

For these allies, FEBAG’s platform fit into a broader political message: condemning Turkey for abuses that continued after the military coup, despite the country’s professed transition to democracy with the 1983 elections. Expressing their support for FEBAG, West German DGB representatives disparaged the “immoral” 20,000 DM sum as a “shameless exploitation of your emergency situation in the service of financing a military dictatorship, which is painstakingly trying to hide behind a guise of democracy.”Footnote 126 The West Berlin Turkish Youth Association, which like many left-wing organizations criticized Cold War militarism, connected FEBAG’s platform to a broader critique of Turkey’s geopolitical ties to NATO and the United States. Given that the military exemption fees were going to the defense budget, the association insisted that supporting FEBAG would help “liberate Turkey from the yoke of the NATO aggressor,” “ensure the security of Turkey against imperialism,” and “protect the democratic rights of working people.”Footnote 127

West German newspapers, which were likewise eager to criticize the abuses of Turkey’s military government, expressed sympathy for FEBAG. The Westfälische Rundschau argued that the 20,000 DM sum was “immoral,” described it as “plundering,” and suggested that the Turkish government was using “robber baron methods” to steal the migrants’ money.Footnote 128 As Hanover’s Neue Presse put it, “Ankara apparently values the foreign currency more than the young soldiers.”Footnote 129 Another publication drew a parallel to the Ottoman Empire – frequently used as a negative foil to highlight the glory of West German democracy against Turkish authoritarianism – during which young men sold into slavery and military service were forced to “passively acquiesce to their fates.”Footnote 130 Forceful quotations from FEBAG’s supporters hammered the message home. “We work and work and save a bit, and then we send the money to our government,” one supporter complained.Footnote 131 “The government does not want us at all. They just want the money,” another complained. In the most memorable quote, which allegedly “shocked” reporters, one man hyperbolized: “The easiest thing you can do is cut off your index finger because when you’re missing a body part, you don’t have to go to military service.”Footnote 132

Bolstered by West German media coverage, FEBAG successfully reshaped Turkish policy. In May 1984, just two months after FEBAG’s founding, Turkish Defense Minister Yavuztürk announced the existence of a proposal to reduce the price but cautioned the activists not to get their hopes up.Footnote 133 Although Yavuztürk did not mention FEBAG directly, his justification for the proposed reduction echoed the organization’s main talking points. “Our citizens abroad consider this price too high and report that it is a heavy burden,” he noted, adding that individuals who took out predatory loans often had to pay an additional 10,000 DM in interest, for a total of 30,000 DM.Footnote 134 The proposal was successful: a month after Yavuztürk’s announcement, the government submitted a bill to parliament decreasing the price from 20,000 to 15,000 DM, reducing the length of service from twenty to eighteen months, and raising the age deadline from thirty to thirty-two.Footnote 135

Still not satisfied, FEBAG continued to demand a reduction of the sum to 5,000 DM and increased their efforts to lobby politicians. In November 1984, the SPD fraction of the Hamburg city council petitioned the state senate to mitigate the problem by guaranteeing that the young men be allowed to return to Germany without losing their jobs even after serving the full eighteen-month military service, and the state senate enacted the law the following spring.Footnote 136 West German politicians’ willingness to accommodate young Turkish migrants made the Turkish government’s continued refusal to lower the price to 5,000 DM all the more frustrating. By 1986, FEBAG had developed more creative ways of lobbying, including protesting in front of eight Turkish consulate offices throughout West Germany while wearing nothing but their pajamas. As the organization elaborated in a flyer, “Up until now, we have worn suits and ties, and nevertheless we were ignored by the Turkish authorities. Now we are going to show up in pajamas and nightgowns.”Footnote 137

Despite such stunts, FEBAG’s 5,000 DM goal never materialized. Even though Turkey reduced the price to 10,000 DM in 1988, the activists continued to portray themselves as “victims.” In an elegant poem speaking to Turkish migrants’ larger sense of betrayal, one activist echoed the oft-touted notion that the Turkish government viewed them as little more than “remittance machines”: “Have you ever worked abroad? Do you know what it means to be a migrant? Do you understand the younger generation? You have your palms open, expecting something from our wallets. All the laws you have passed are for yourselves. You want to take advantage of the destitute migrants … We are not remittance machines. We are Turkish youths living abroad.”Footnote 138

*****

Whether redirecting West German development aid, urging guest workers to send remittance payments, or squeezing money out of young military-age men, the Turkish government’s opposition to return migration throughout the 1970s and 1980s reflected a consistent trend: prioritizing national economic goals over guest workers’ and their children’s needs. Whereas the Turkish government in the early 1960s valued the guest workers for their ability to return and contribute to their homeland using their knowledge and skills cultivated in West Germany, by the 1970s and 1980s the government derived the migrants’ value as citizens precisely from their absence from their home country. Turks living in West Germany remained official citizens of Turkey, but their value to the nation was no longer tied to their physical presence within the borders of the Turkish nation-state. Instead, it was based on their ability to contribute to the country’s economy by remaining abroad, by not inundating the overburdened Turkish labor market with their unwanted bodies, and by investing Deutschmarks in their homeland.

This new set of relations reflected Turkey’s efforts to position itself within the broader world and to make sense of its own identity. In practical terms, the obsession with guest workers’ Deutschmarks was fundamentally the product of Turkey’s macroeconomic struggles as it adjusted to its outward orientation in the age of global neoliberal capitalism and attempted to alleviate the debt crisis of the late 1970s. But it also reflected a deeper crisis of Turkey’s national identity as those at home grappled with redefining their relationship to the Almancı 3,000 kilometers away.

To conceal their obsession with coopting guest workers’ Deutschmarks, both the government and corporations – from banks to cigarette companies – used nationalist rhetoric that sought to embrace the ostracized migrants as core parts of the nation, or the vatan. But guest workers saw through this rhetoric. Many sincerely wished to return to their home country and could have greatly benefitted from Turkey’s cooperation with West Germany’s bilateral development programs promoting return migration. Instead, they felt as though they were being abandoned and exploited by the government of their homeland. The novelist Bekir Yıldız’s satirical interpretation – that guest workers should even “give up eating” for the sake of their home country’s struggling economy – rang true. Manipulation had created mistrust.