The self-portrait empowered early modern women artists to deliver distinctive statements about their creative identities.Footnote 1 Barred until the early nineteenth century from live-model drawing within the context of their academic training, women found other outlets for studying the body, regularly focusing their attention on figures to which they could devote close and unfettered observation, which is to say friends, family and self.Footnote 2 Focused on paintings and drawings, however, studies of the topic have largely omitted prints, neglecting to contemplate how consideration of this medium might nuance our understanding of women’s contribution to the genre. From the time print workshops were established in the sixteenth century, women were regularly tasked with the reproduction of historical and allegorical subjects their male peers had invented, including narratives that featured the nude, the study of which the academy had long banned them. Conversely, even as male artists from the late fifteenth century enthusiastically embraced the self-portrait print as a site for broadcasting their distinctiveness as authors and inventors, female artists and creators were notably less eager to incorporate it into their practice.Footnote 3 Print travelled far and wide, enabling men who etched or engraved their self-portraits to flaunt their accomplishments and fulfil their aspirations of undying fame. Women’s reliance on the same techniques for self-advancement was substantially more troubled, however. By showing themselves off, by literally exposing themselves to the public eye, they risked not covering themselves in glory but – like the widely shared medium in which the images were created – inviting comparison of themselves with the common street-walker.Footnote 4 These and other circumstances suggest that a rather different set of criteria was at stake when it came to how women approached making prints and especially what they understood to be suitable themes for their involvement with them. This chapter examines several self-portrait prints from the eighteenth century to explore some of the concerns that went into how women shaped their appearances with the knowledge that, by making themselves subjects for everyone to see and potentially own, they were walking a fine line between establishing their prominence and committing a potentially perilous offence for which they would be judged, often in terms that assailed their virtue and/or questioned their beauty. Loath to attract this sort of attention, eighteenth-century women, this chapter finds, either avoided using the medium for self-portrayal altogether or leaned heavily on male authority figures and veiled allusion to account for and justify their representations.

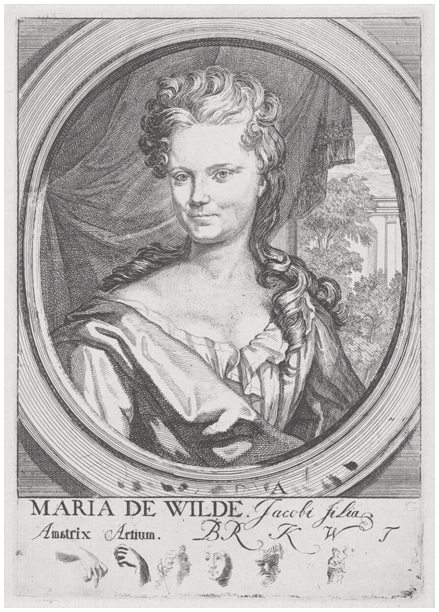

Two etchings by Maria de Wilde (1682–1729) from the very beginning of the eighteenth century bring this discussion into focus, pointing to the challenges female creators would face for the next 100 years and beyond. Without precedent – apart from etchings by Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678) – the works illustrate the care de Wilde put into crafting her image, mindful that the choice not just to pick up the etching needle but also to make herself the topic of print were hazardous undertakings. Riding on the reputation and social status of her father, Jacob de Wilde (1645–1721), a high-ranking officer in the Amsterdam Admiralty, Maria de Wilde represents these acts as expressions not of fierce independence but of filial piety. In the first of these self-portraits (Figure 1.1), likely created around 1700 and possibly just shortly before the second, she renders herself bust-length, bordered by a fictive oval frame below which the words ‘Maria de Wilde Jacobi Filia’ [Maria de Wilde, daughter of Jacob] are prominently inscribed. The decision to include these words may in part have been motivated by the ways in which sixteenth- and seventeenth-century women printmakers signed their works. Many women in the early modern period acquired proficiency in the medium under the tutelage of their husbands, fathers, and other male relations in order that they might contribute to the activities of running the family workshop.Footnote 5 Such is the case, for example, with Barbara van den Broeck (born c. 1558/60), daughter of Crispin van den Broeck, and Susanna Maria von Sandrart (1658–1716), daughter of Jacob von Sandrart, who both signed a number of their works referring to themselves as ‘filia’, daughters of their prominent printmaker fathers. Unlike these, however, de Wilde was not the progeny of a well-known male engraver, and her images did not therefore function as advertisements for the products of a familial publishing enterprise. Instead, de Wilde was an amateur, a circumstance she spells out with a second Latin inscription, ‘amatrix artium’, or female lover of arts. Her etching thus belongs to a large body of work produced in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by women who belonged to the moneyed, intellectual and leisure classes, many of whom dabbled in producing prints, primarily etchings.Footnote 6 Unconstrained by the pressures of working as an artist to make a living, amateurs like de Wilde had greater freedom to experiment and to overcome possible blunders. It can be no accident that the first full-page self-portrait prints were created not by established female painters or printmakers but by non-professionals, including what is very likely the first one of its kind executed by fellow countrywoman Anna Maria van Schurman, an accomplished scholar who made art on the side.Footnote 7 This circumstance, notwithstanding, de Wilde’s allusion to being the ‘filia’ of Jacob communicates her sense of the need to account for her practice through reference to him.

Figure 1.1 Maria de Wilde, Self-Portrait, c. 1700. Etching, 20.8 × 14.6 cm.

What were some of the pitfalls for women of circulating their likenesses in print? To examine the question, it is helpful to return to the example of Anna Maria van Schurman, who in 1633 at age 26 produced a bust-length etching of herself (Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-OB-59.344), an image that sets out to navigate the highly gendered divisions between the public (male) and private (female) spheres that were a condition for working in the medium of print from the sixteenth century through the period this volume encompasses.Footnote 8 Modestly clothed, van Schurman arranged her appearance to avoid impropriety, hoping no doubt that this would permit her etching to enter into circulation without causing too much of a stir. She wears her chin length, tightly curled hair loose and is clothed in a heavily brocaded dress with a lace neckline that covers her décolleté and fastens firmly and chastely under the chin. In front of her, she had placed a large cartouche resembling a fictive scroll that partially obscures her torso from view. Made of a substance that is sizably thicker than paper, a solid, possibly stone-like material, the frame functions as a sort of impenetrable buttress or shield between van Schurman and the viewer, giving physical form to her need to find shelter, conscious that even as she attempts to take cover behind it, she was baring herself to a level of scrutiny that was incompatible with contemporary notions of comportment becoming to a woman.Footnote 9

The following words appear on the cartouche: ‘Neither my mind’s arrogance, nor my physical beauty/Has urged me to engrave my portrait in ever-lasting bronze./ It was, rather, the impulse to not work on more powerful subjects on my first attempt,/ If perhaps this crude stylus (my novice as an artist) were forbidding better ones’.Footnote 10 Signalling her unwillingness to describe herself in overly complimentary terms, the inscription – in keeping with ideas of womanly humility and the sentiments commonly expressed by amateurs about their lack of expertise – reflects van Schurman’s renunciation to claims either of beauty or skill, a statement that might lead one to conclude that she held little of her own handiwork. Shortly after etching the work, however, she gifted it to the leading Dutch intellectual Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), likely in a bid to engage his interest in her scholarship. Taking the form of a poem, his intensely personal response offers insights into how van Schurman’s printmaking venture was received by a leading male intellectual of her time. Written on 2 December 1634, Huygens’s verse reads:

An ekphrasis of the picture, Huygens speculates why van Schurman’s etching failed to include her hands that have been sullied by ink. Slyly honing in on her desire to make herself the subject of a print as an initiative that transgressed the boundaries of feminine (read private or non-public) behaviour, Huygens identifies her role in authoring the image as a sort of crime, wilfully ignoring in the process van Schurman’s best efforts to present herself with appropriate reserve. His poem instead aims to ‘out’ her by imagining that her project to make prints, like some original sin, has indelibly stained her hands and that she has inserted the cartouche in an effort not to thwart access to her body, but to conceal the evidence of her guilt. To make matters worse, he uses a sexual metaphor, ‘the first cut’, to describe her decision to pick up the stylus to score the plate, describing the act as a self-inflicted hurt that can never be undone. Van Schurman may be a virgin, but for Huygens her choice to incise her own image has forever spoiled her maidenhood: the girl is now a slut.Footnote 12

Portrait paintings, drawings, miniatures and medals have long participated in elaborate rituals of gift-giving and receiving with the aim of currying favour and cementing renown.Footnote 13 Van Schurman’s reliance on these very habits of exchange and her decision to present Huygens with a print is indicative of her understanding of the role the medium could play in managing her public persona, as it had done for men from the time a means to create repeatable images was invented. Remarks by Crispin de Passe in his Les Vrais Pourtraits De quelques unes des Plus Grandes Dames de la Chrestiente, desguisées en Bergères (The True Portraits of several of the Greatest Women of Christianity, disguised as Shepherdesses) of 1640, might have given her reason to reconsider the suitability of her choice of gift, however, especially the act of bestowing the etching on a man. By imbuing his female subjects – well-known ladies from the aristocracy and upper middle class – with pseudonyms and presenting them in pastorally inspired costumes, de Passe says he aimed to disguise the women’s identities in order to deter men from declaring that they had the portraits of their ‘beloveds’ in their pockets.Footnote 14 A sartorial invention of the seventeenth century, the pochettes into which de Passe imagines these pictures would be slipped, communicates how prints lent themselves to being carried upon and even close to the body.Footnote 15 When van Schurman gave Huygens her etched self-portrait on paper, a thing that by its nature is tactile and designed to be touched, fondled, even pocketed, she also unwittingly handed him the means not just to regard but even to handle her in ways that we now see provided occasion to imagine her in disturbingly intimate terms. One can well imagine de Wilde’s hopes to be sheltered from this sort of consideration when she referred to her kinship with Jacob. By conspicuously describing herself as ‘Jacobi filia’ she effectively inserted her father between herself and the male beholder, making it much more challenging for the user to treat her image in ways indicated by Huygens and de Passe.

Relying on conventions introduced to portraiture by Anthony van Dyck, de Wilde portrays herself against a swag of drapery and a sliver of landscape with the columns of a classical façade beyond. With bare décolleté and soft curls piled high on top of her head and tumbling over her shoulders, her modish, upper-class self-presentation is strikingly different from that of van Schurman. A series of stray etching marks in the margin of the frame and non-referential letters next to her inscription suggest that she conceived the etching as a trial proof and that the work was never intended for widespread circulation, a circumstance that may explain her somewhat voluptuous portrayal. Like van Schurman, however, de Wilde concentrates on her upper torso, omitting her arms and hands. With this in mind, it is striking that a pair of hands appears among the doodles that occupy the bottom of the sheet. Eerily disembodied, they hang suspended in mid-air just beneath the words ‘amatrix artium’, suggesting a possible link between them and her status as an amateur. The one on the left with index and middle finger gently curled inward seems poised to hold a small delicate instrument, while the one on the right with all digits pointing towards the palm seems ready to grip or hold something larger and more substantial. Even though it is impossible to state with any certainty what the artist had in mind, the gestures are not incompatible with those of a hand holding an etching needle in one and a matrix or tablet in the other. If this is the case, then the artist, while omitting these details from her self-portrait, was pondering not only how to represent her activities as an etcher but also, more importantly, how to render them in a way that would not cause her embarrassment.

This brings us to the second of de Wilde’s etchings, one that does show her in the process of working on a plate. A frontispiece to Signa Antiqua e Museo Jacobi de Wilde of 1700 (Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles), the print prefaces de Wilde’s best-known publication, a set of sixty signed etchings that replicates Egyptian, Roman and Renaissance statuettes in her father’s renowned cabinet or ‘museo’.Footnote 16 By comparison with the former, this one shows her more plainly attired, wearing a dress that covers her chest, and strappy, Roman-style sandals in keeping with her project’s antiquarian focus. Seated beneath a sculpture of Apollo, de Wilde renders herself in the act of drawing on a matrix. Occupying an elevated position on a pedestal carved with a Latin inscription referring to de Wilde’s role in reproducing her father’s collection, Apollo reaches down to hand her a statuette, bestowing on her the gift of art and the theme of her book.Footnote 17 To the right an impish looking Mercury similarly seems intent on presenting her with a double-headed Janus bust, with the head of a man on one side and that of a woman on the other. Following in the tradition of earlier professional female printmakers, the image expresses an understanding of printmaking as an activity in which women engaged with appropriate male oversight: de Wilde could reasonably expect her project to meet with approval because she conducted it under the auspices of her father and the paternalistic gaze of the gods. If de Wilde’s first self-portrait conveys her anxiety about how to portray the act of producing etchings, her second finds a solution in the patronage of an array of male authority figures.Footnote 18

The challenges and consequent hesitancy women felt about portraying themselves in print are epitomized by the skilled and highly successful painter Angelika Kauffmann (1741–1807), an artist who did not otherwise shy away from circulating her inventions in print and who is known for her drawn and painted self-portraits.Footnote 20 Scholars ascribe to her an etched self-portrait created around 1764, which survives in what may be a unique impression (Figure 1.2), likely an indication that the edition was small.Footnote 21 Modest in scale, it measures just 15.5 × 11.8 cm and shows the sitter bust-length, clothed in a prim, high-necked, lace-trimmed dress. Her restrained choice of attire contrasts with the rather more flamboyant mode in which she presents herself in painting and drawing, underscoring Kauffmann’s sense of the necessity to employ the medium judiciously and above all conservatively for purposes of self-presentation. This print is supplemented by instances of what Angela Rosenthal has called works that rely on a range of ‘symbolic, allegorical and mythological masks’ to expand what we understand by the act of self-portrayal.Footnote 22 Examples of these include La Speranza (Hope) of 1765 (London, British Museum (hereafter BM) 1852,0214.128) and Woman Resting her Head on a Book of 1770 (The New York Public Library, New York, 62758), etchings that feature turbaned sibyl-like figures leaning on volumes, whose role has been recognised as functioning to thematize broadly the young artist without resorting to slavish reproduction of her likeness.Footnote 23 A dreamy, melancholically inflected image, La Speranza reproduces the Raphaelesque reception piece Kauffmann designed for admission to the Accademia di San Luca in 1765, a work that seems in turn to have inspired Woman Resting her Head on a Book.Footnote 24 Even as La Speranza is usually accepted as a self-portrait, the female personification is so idealised as to function as an allegory of the young artist’s aspirations for a successful career.Footnote 25 Together the etchings reflect Kauffmann’s efforts to use print to reflect on her own creativity in ways that removed her mimetic likeness from becoming the subject of contention.

Figure 1.2 Angelika Kauffmann, Self-Portrait, c. 1764.Footnote 19 Etching, 15.5 × 11.8 cm.

Kauffmann’s reluctance to produce etchings of her own visage does not mean that prints of her were uncommon. To the contrary: engravings that captured her appearance enjoyed broad distribution.Footnote 26 Products of professional printmakers – including works by William Ridley (1764–1838), Ludwig Sommerau (1756–1786), Thomas Burke (1749–1815), and others – the pictures, which were not commissioned, amount to what we might term ‘unauthorised’ self-portrait prints. Portrait prints after painted self-portraits by Maria Cosway (1760–1838), Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757), Élisabeth Sophie Chéron (1648–1711), and Rhoda Astley (1725–1757), suggest, that the practice was by no means restricted to Kauffmann. ‘Ipsa Pinxit’ (Painted by herself) and ‘J. Elias Haid sculps’ (Engraved by Johann Elias Haid) are inscribed on a c. 1757–1767 mezzotint by Johann Elias Haid after a self-portrait pastel by Rosalba Carriera, a use of Latin print terminology that is duplicated in works by François Chéreau after Élisabeth Sophie Chéron (London, BM O,6.68) and by James McArdell after Rhoda Astley (Royal Academy of Art, London, 12/2323).Footnote 27 Together the images point to the role male printmakers played as self-appointed creators of the female self-portrait print.

A market clearly existed for portrait prints of accomplished women, but the terms under which they were created were to a large extent dictated not by their female makers, but by men. Two etchings, one by Joseph Wagner (1706–1786) after an image of herself by Rosalba Carriera (Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-2007-271) and another by Lavinia Spencer (1762–1831) after Richard Cosway (1742–1821) (London, BM 1857,0520.303), variously illuminate this point. Wagner’s image was based on a composition Carriera presented to the influential art collector and British Consul to Venice, Joseph Smith, just before she turned blind around 1746. Among Carriera’s most significant patrons, Smith likely received the pastel in recognition of his friendship and support of her art.Footnote 28 Clearly impressed both with the work and with her extraordinary gift to him, Smith hired Wagner, who had founded a flourishing printmaking enterprise in Venice, to copy the pastel, turning the intimate souvenir into an occasion to produce a public statement about both the skilled female artist and himself. The inscription below reads: ‘Effigiem manu ipsius pictam; sibique dono datam. Joseph Smith Magnae Britanniae Cos. Aenea tabula propagari curavit’ (A picture by her own hand; a gift given to him. Joseph Smith, British Consul, has arranged [for it] to be dispersed with this copperplate). The wording expresses a sense of the male personage with the power and influence to receive a gift of this magnitude and to commission a reproduction of it, ensuring not only that the work was widely disseminated but also that it received the sort of recognition to which the Consul knew he and its subject were entitled.

An etching of herself by Lavinia Spencer similarly points to men’s role in mediating the female self-portrait print. Undisputedly the hand of the amateur, the representation shows the artist full-length, seated at a desk on which a quill pen and ink stand.Footnote 29 Spencer’s role in authoring the design is complicated, however, by an inscription on an impression at the British Museum (1857,0520.303), whose verso reads: ‘Etched by Lavinia Spencer / her Ladyship’s portrait after Cosway, touched by herself’, suggesting that the work was based not on careful self-observation but on a sketch by Richard Cosway. A gifted portraitist and miniaturist, Cosway became the principal painter to the Prince of Wales and moved in the sorts of elite circles to which the Spencer family belonged, producing portraits of them at various stages in their lives.Footnote 30 It is quite possible, then, that he produced the sketch on which Lavinia based this print. Indeed, qualities of the work’s hand-colouring, especially the young woman’s rosy lips and rouged cheeks bear distinct similarity with the methods Cosway used to tint the faces of his delicately shaded miniatures, suggesting that she was emulating qualities of his style. Assuming an attitude of carefree contemplation, Spencer dressed in a frothy, feminine gown and with her index finger raised to her lip is presented regarding the pages before her, seemingly lost in a state of dreamy reflexion. Rendered not as a serious artist, however, Spencer surrenders herself to the light-hearted vision of the female imagination imposed on her by a fashionable male painter of her day.

The so-called Oprecht Verhaal wegens het portraitteeren van Mejuffrouw Maria van der Wilp, door Marinkelle, portraiteur in miniatuur (Fair Account of the Portrait of Miss Maria van der Wilp by Marinkelle, Miniature Portraitist) of 1772 reinforces the outsized role men played in arranging how women would appear in print. Not a self-portrait per se, the published text instead offers meaningful insights into the sorts of aesthetic considerations eighteenth-century women brought to bear on their printed self-likenesses as well as into the role men believed they should rightfully play in determining just how their female sitters should look. Authored by Joseph Marinkelle (1732–c.1776), the Oprecht Verhaal represents the miniaturist’s defence of his portrayal of the poet Sara Maria van der Wilp (1716–1803). The text is the result of an acrimonious disagreement that arose after van der Wilp commissioned Marinkelle to draw her likeness in preparation for the professional engraver Jacobus Houbraken (1698–1780) to render it in print. According to the custom of the day, her portrait was to appear at the beginning of her first published volume of poetry.Footnote 31 Told from Marinkelle’s point of view, the text informs us about van der Wilp’s commission, stating:

She [Sara Maria van der Wilp] asked me [Joseph Marinkelle] for the best way this [her portrait] should happen, and I advised her in the common modern way. This was not her choice, however. She found a great many portraits, surely known to her through the beautiful print collection once possessed by her father, to be very stiff: the hats changed almost every month; the clothes, the corsets etc. had no grace: in short, she preferred to be drawn in a loose style, or as she called it in antique dress, without hat, and with a bared bosom.Footnote 32

In seeking a representation of herself in the ‘antique’ manner, van der Wilp was aiming, it seems, for an image that would transcend the specifics of time and place and endure as a monument to her talent and ability, a visual trope that had long established itself as viable for visualising male distinction. Recognising the risks to these aspirations, however, Marinkelle states that he sought to dissuade her by placing before her examples of works by Anthony van Dyck and Bartholomeus van der Helst.Footnote 33 He said he begged her not to deviate from the custom of presenting herself in a corset with a hat over her face, and neck and bosom covered, but that van der Wilp persisted, saying this was how she wished to appear.Footnote 34 Marinkelle rendered her accordingly, and with a few agreed-upon edits, the preparatory drawing was handed to the engraver to reproduce in print. Upon its release to the public, however, the miniaturist states that he was summoned to her house and told that ‘everyone was screaming about the ugliness of the published work. They said that she looked like a fishwife, a Dragoon of a woman, that one would sooner choose to eat than to fight and furthermore a shameless whore, with breasts like cow udders’.Footnote 35 Van der Wilp’s wrongdoing for which Marinkelle partially bore the brunt, causing him to publish a rebuttal in the form of the Oprecht Verhaal, was to miscalculate her viewers’ receptivity to her portrayal all’antica. If only she had listened to him, Marinkelle states, the matter would have turned out well – van der Wilp exemplifies the fate of women who either fail to heed the counsel of men or take the task of self-representation into their own hands. While the hateful (not to say ageist and misogynistic) comments directed at her seem out of proportion to her alleged fault, the accusations are in keeping with what we have already observed about print’s propensity to attack women who fail to conform to normative ideas of appropriate female self-conduct. Van der Wilp’s capitulation to convention is signalled by her decision to reissue her portrait, this time with her head and chest covered in accordance with what Marinkelle had all along advised her to do.

Today we are all too acquainted with the propensity for the ‘selfie’ to elicit derogatory and hostile comments on the internet and social media about women’s physical attributes and their perceived attractiveness.Footnote 36 Huygens’s censure of van Schurman and the outcry over van der Wilp’s ‘loose’ portrayal thus have a surprisingly familiar ring. Over half a century ago, the arrival of the worldwide web provided an amplified version of the opportunities made possible by the invention of a means to create repeatable images; and there is a resonance in its characterisation as ‘promiscuous’, mirroring aspects of the early modern reception of print and its tendency to ‘body shame’ those bold or foolhardy enough to use the medium to circulate their own likenesses.Footnote 37 All of this is to say that women’s activities in the public eye, not least the highly contentious representation of themselves, have long been a perilous undertaking. In the period this volume examines, it is clear that while the handful of women who explored the self-portrait print as a vehicle for celebrating their individuality and accomplishments were courageous, their success mostly hinged either on winning over or yielding to the approval of men. In hindsight, the project can at best be described as a mitigated success.

In April of 1830, performing a service to future historians, Sir William Cosway asked his ageing relative, the artist and educator Maria Cosway, née Hadfield (1760–1838), for ‘some memoirs’ of her life. He had made this request before, and now – finally – his persistence prevailed. The following month, Maria Cosway responded with a richly narrative letter, taking pride in the details of her artistic training in Florence, her marriage to the English portraitist Richard Cosway in 1781, her ensuing entry onto London’s artistic scene, her quick successes as an exhibiting painter, and one of her most hard-won achievements in print – a publication she had initiated and executed herself. She also reflected on the hurdles she faced as a woman. For as Cosway knew all too well, she lived in a time and place in which women’s political and legal rights were formally, if not always in practice, subsumed under those of their fathers and then their husbands. ‘Had Mr. C. permited [sic] me to paint professionally’, she lamented, ‘I should have made a better painter[,] but left to myself by degrees instead of improving I lost what I had brought from Italy of my early studies.’Footnote 1 This clause has long been taken as evidence that Cosway did not pursue or, for the most part, even entertain professional aspirations in any artistic medium.

However, Maria Cosway’s repeated engagement with an expressly commercial form of print at the end of her exhibiting career strongly challenges her retrospective account. From 1800 to 1803, she worked on five artistic, didactic publications. Her contributions to these ever-more ambitious series – all but one glossed over in her autobiographical letter – did, in fact, fit the definition of professionalism at the time as it applied to painting, print, and other artistic enterprises: a pursuit undertaken for remuneration. Her final project, moreover, allows us to see how three women used art to probe the roles, expectations, and constraints that members of their sex automatically faced in the Revolutionary world. This chapter will provide a brief overview of Cosway’s public artistic trajectory and then consider each of her printed publications in turn; along the way, it will introduce the activity of other female artists and writers with whom Cosway’s work regularly intersected and engaged.

Maria Cosway was born in Florence, Italy, where her parents ran a popular series of inns for British travellers. She practised art from a young age.Footnote 2 As she described at length in her letter to Sir William,

At eight years I began drawing … [and] took a passion for it … I was … put under the care of an old celebrated lady [Violante Beatrice Siries, later Cerotti], whos [sic] portrait is in the [Uffizi] Gallery … This Lady soon found I could go farther than she could instruct me, & Mr. [Johan] Zofani being at florence my father ask’d him to give me some instructions. I went to study in the gallery of the Palazzo Pitti, & Copied many of the finest pictures. Wright of darby [Joseph Wright of Derby] passed only few days at florence & noticing my assiduity & turn for the Art, sprung me to the higher branch of it. My father had a great taste & knowledge of the arts and … in every way contrived to furnish my mind.Footnote 3

In 1777 she began to visit Rome, where, she recalled, ‘I had an opportunity at knowing all the first living artists intimately; [Pompeo] Battoni, [Anton Raphael] Mengs, [Anton von] Maron, and many English artist[s]. [Henry] Fusely with his extraordinary Visions struck my fancy. I made no regular study, but for one year & half only went to see all that was high in painting & sculpture, made sketches’.Footnote 4 Cosway was raised Catholic, and claims to have wanted to become a nun upon her father’s death in 1776. Instead, three years later, the family moved to London. Cosway arrived in the British capital with letters in hand for ‘all the first people of fashion’: i.e., the artists ‘Sir J[oshua]. Reynolds, [Giovanni Battista] Cirpiani [sic], [Francesco] Bartolozzi, Angelica Kauffman’.Footnote 5 With her mother worried about finances, Maria Cosway (Hadfield at the time) made a quick, profitable match with the fashionable portrait painter Richard Cosway, a Royal Academician of London’s recently founded Royal Academy of Arts; they married in 1781. She made her own exhibiting debut at the Academy later that year and, through 1801, displayed forty-two works in its annual show: eight portraits and thirty-four narrative scenes, frequently from literary sources.Footnote 6 All but three of these pieces hung in the Great Room, the Academy’s most prestigious space. Surviving images suggest that Cosway’s canvases were often hung quite centrally.Footnote 7

In line with this pride of place, Cosway found herself well received from the start as an exhibiting painter. For her induction in 1781, she submitted three narrative scenes – one classical, one from Tasso, and one from Shakespeare – all of which appeared in the Great Room. In 1782, she sent in four narrative paintings, again all placed in the Great Room, including her celebrated The Duchess of Devonshire as Cynthia.Footnote 8 Although it was only her second year exhibiting, this showing led a critic for the Morning Chronicle to conclude, ‘she is the first of female painters, and inferior only among the male sex to her husband, and to Sir J. Reynolds’.Footnote 9

Also from the beginning, and mirroring Angelika Kauffmann (1741–1807, one of the Academy’s two female founders), Cosway’s reputation rapidly extended beyond Academy walls through the medium of print.Footnote 10 Signalling her quick and lasting popularity, two of Cosway’s three debut works were published as mezzotint engravings; ultimately, more than a dozen of her exhibited works were reproduced and sold in print.Footnote 11 Some of these were executed by London’s leading male printmakers, including Francesco Bartolozzi and Valentine Green. Others came from the hands of women such as Emma Smith, later Pauncefote (1783–1853), who was both an exhibiting painter and a printmaker.Footnote 12 In 1801, Smith engraved in mezzotint two of Cosway’s exhibited paintings — nearly two decades after they had appeared on display.Footnote 13 Smith had debuted at the Academy herself in 1799, and would exhibit a mélange of twenty-seven portrait, narrative, and landscape works through 1808 as she simultaneously established a growing reputation as an engraver. In 1805, the poet and novelist Charlotte Smith wrote to her publisher, hoping to hire Emma Smith to provide additional illustrations for one of her works; she had been ‘struck’ by Smith’s talent when they met while visiting a mutual friend:

If any new plates are intended, I think that, if the drawings I saw a few days ago are done by the young Lady who shew’d them to me of the name of Smith, the daughter of an artist, she is capable of seizing my idea’s & would make beautiful designs … I was extremely struck with two little designs from the Vicar of Wakefield & think them almost too masterly for so young an artist.Footnote 14

Cosway and Emma Smith were in good company – in these same years, hundreds of women were becoming increasingly active in London’s public art world, a phenomenon that was both commended and critiqued. Satirical prints began to ridicule female portraitists as early as 1772, and continued through (and past) the early nineteenth century. Some of these lampoons extended their ambit to Cosway herself.Footnote 15 For instance, in A Smuggling Machine or a Convenient Cos(au)way for a Man in Miniature, issued by the prominent publisher Hannah Humphrey (1745–c. 1818) in 1782, we see Richard Cosway, standing, immersed in his wife’s petticoat.Footnote 16 Beyond mocking Richard Cosway’s size (he was known to be physically short), the image literally pictures the idea – and anxiety – that through their public achievements, women could upstage professionally prosperous men.Footnote 17 Four years later, another printed satire placed Maria Cosway in a Bedlam cell, parodying her predilection for the Fuselian sublime.Footnote 18 This image, too, was published by a woman, the lesser-known Elizabeth Jackson (fl. 1785–1787), and echoed some journalists’ growing disapproval of Cosway’s pursuit of the ‘grand’, ‘horrible’, and ‘extravagant’ in her exhibited art – all, by implication, visual categories that they deemed should be gendered male.Footnote 19

Perhaps such frictions influenced Cosway’s own view of her career. Her letter to her nephew was not the first time that she described feeling restricted in her professional aspirations by her sex and, relatedly, her marriage. In November 1797, Cosway shared with the Academician and diarist Joseph Farington that ‘she begins many pictures but soon grows tired – having no obligation to finish them she requires a necessary stimulus; had [Richard] Cosway allowed Her to sell her works it would have been otherways [sic], finishing would have been a habit’.Footnote 20 In the lexicon of the time, for Cosway to have sold her works would have meant that she painted professionally, or at least aspired to do so; to practise art (or other cultural pursuits including music, writing, and even embroidery) as a professional was to do so with the goal of earning money.Footnote 21 This concept of professionalism was not new, and had long included women artists under its ambit.Footnote 22 It was, however, evolving and gaining appeal in these exact years; in 1792, in her foundational A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, the philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) had written that ‘to earn their own subsistence’ was, for women, ‘the true definition of independence’.Footnote 23 The conservative backlash to Wollstonecraft’s ideas was immediate and fierce. Still, as the 1790s progressed, growing numbers of women attempted to earn money in new ways, including through their art – particularly by exhibiting their paintings and drawings, and by working in print with an eye towards publication.Footnote 24

It was at the end of this same decade, soon after her conversation with Farington, that Maria Cosway too turned to print. Unlike her paintings, with which she faced pecuniary restrictions, here she focused on works that were meant to be serial, published, and sold.Footnote 25 It is not clear why this distinction seems to have been one of media; perhaps it helped that she first entered the print market through a joint project with her husband. Yet no matter the impetus, in 1800 Cosway contributed to three publications, followed by even more elaborate schemes in 1802 and 1803. First came the Imitations in Chalk from Drawings by R. Cosway, R.A., thirty-six plates of soft-ground etchings by Cosway after sketches by Richard. Published by Rudolf Ackermann in 1800, the Imitations were issued in six parts of six prints each and meant to function as a drawing book, providing a range of models, subjects, and compositional formats for study — from sketchy figural outlines to full narrative scenes.Footnote 26 The German-born Ackermann had come to London in the late 1780s and quickly became a leading seller and publisher of decorative prints, colour-plate books, and popular periodicals. By 1795, his business establishment on the Strand (soon called The Repository of Arts) hosted a drawing school, library, and gallery, and also sold art-making materials.Footnote 27

The Imitations fit this commercial drive. Richard Cosway had long been a leading society portraitist: he had exhibited in London’s shows since their inception in 1760, became official painter to the Prince of Wales in 1785, and, over the course of his career, saw more than 160 individual prints made after his paintings. An instruction book after his compositions presumably would have had considerable appeal and, of the three printed series reproducing his works (one appeared in 1785, another in 1826), the Imitations were by far the largest and most complex. Their didactic framework, moreover, mirrored the language with which other artists, such as the botanical painter Mary Lawrance, later Kearse (fl. 1794–1830), were commencing projects in print at the time – from 1799 to 1802, Kearse published three collections of floral etchings while promoting herself as an employable instructor.Footnote 28 Although it is not clear why Maria Cosway, rather than one of Ackermann’s printmakers, executed the etchings, the Cosways’ partnership in print was not new; one of her earliest prints seems to be an etching of cherubs after Richard, made in 1784.Footnote 29

Whether Maria Cosway found a new passion for print, or Ackermann recognised unexploited commercial potential, this first project seems to have been pivotal. Cosway contributed to four more publications in the next three years, at least one of which she initiated herself. First, a few months later in 1800, Ackermann released a two-part series after her compositions: A Progress of Female Dissipation and A Progress of Female Virtue. This time, the Flemish Anthony Cardon provided the engravings after, as the title page advertised, ‘Original Drawings by Mrs. Cosway’. The series presented two parallel lessons: a cautionary tale about the perils of being a woman, from childhood to old age, and a model of a virtuous path a woman could aspire to take through life. At least one contemporary noted the homage to William Hogarth.Footnote 30

Both Progresses unfolded over eight plates with descriptive, proscriptive verses beneath each image. In A Progress of Female Dissipation, the protagonist is mocked for vanity and immodesty from her youth, distracted by her own image in a mirror as a child and then, again, while practising music. These traits later lead her to neglect her own crying children and, in old age, dress inappropriately (it is implied) while taking snuff and playing cards. In A Progress of Female Virtue, the opposite story unfolds. As a child, the heroine appears at prayer, reading a book, and then displaying an impulse for charity by giving money to a blind girl on the street; as a young woman, she draws attentively from nature, leaning forward into her craft; she then marries, and tenderly breastfeeds her child; and, finally, as a grandmother, she watches her granddaughter learn to read while her grandson scans news of ‘Lord Nelson’s victory’. Ackermann used Cosway’s designs to experiment with paper colour and white heightening, exactly as he was continuing to publish large-scale reproductions of her painted and drawn works executed by an emerging group of soon-to-be prominent engravers: Samuel Philips, Peltro William Tomkins, and Samuel William Reynolds.Footnote 31

Cosway’s autobiographical letter did not mention these first three publications, nor Ackermann’s large-scale prints after her compositions. It seems, though, that in the process, she was motivated to instigate her only independent project, one that interwove these didactic and visual facets: the Gallery of the Louvre (Galerie du Louvre). This was Cosway’s most ambitious publication and the only printed work she described in her letter. As an object, it is massive: each page measures 56 × 68 cm.Footnote 32 It also reflected a huge personal shift. In 1801, after exhibiting at Somerset House for the last time, Cosway left London for Paris – tales of the Louvre’s newly enhanced collection had recently riveted the British art world – and began to establish a new life for herself, alone. She would return to London only sporadically over the next two decades, as her husband’s health began to fail.

Invigorated and inspired, Cosway worked quickly in the French capital. By February 1802, she had published at least one of the two advertisements she would circulate courting subscriptions for the Gallery, which she described as ‘Correct Etchings of the Whole Collection of the Pictures in the Gallery of the Louvre at Paris’.Footnote 33 At the time, the military hero Napoleon Bonaparte had established firm command of France as First Consul (he would declare himself Emperor in 1804) and, over the course of his campaigns, had pillaged and amassed an extraordinary body of Old Master paintings that now greeted visitors to the Louvre. As Cosway explained in her prospectus, she planned to illustrate the ‘most remarkable works’ in this growing collection by etching their new organization in the Grand Gallery, with ‘An Historical Account of Each Picture’ accompanying every depicted piece.Footnote 34 She itemized the prices per plate for subscribers and nonsubscribers, as well as several of the anticipated etchings. Earlier in her Parisian stay, she had met the entrepreneur Julius Griffiths, who Farington would soon characterize as ‘a Speculator, a Man of much adventure’, and ‘a Man of abilities, but irregular’.Footnote 35 They became business partners, and ultimately published eleven folio-sized plates available in monochrome or hand-coloured, each rendering a full Louvre wall and its hanging; while the etchings of the individual framed works are a bit rough, Cosway’s prints nevertheless show minute attention to composition and detail. These visuals were accompanied by sixty pages of text by Griffiths describing each canvas, the artists involved, extant copies and prints, and relevant anecdotes. By the project’s end (it never reached the full number of intended plates), Cosway had initiated and produced a history of art – an artist’s reading, in essence, of the Louvre’s novel historical hanging, and a didactic project that echoed and extended her own early experiences learning to draw and paint in the Uffizi’s galleries, thirty years prior.Footnote 36

Cosway’s project was prescient, and her timing was apt. In March 1802, the Treaty of Amiens inaugurated the first break in hostilities between Britain and France since 1793. During the following fourteen-month Peace, Britons rushed across the Channel, eager to view the vast changes that had taken place in Paris during a decade of relative impenetrability – changes that included the Louvre’s immensely augmented collection. As British visitors perused the Napoleonic hang, many found Cosway diligently copying works from the walls. By developing a valuable relationship with the Bonaparte family – especially Napoleon’s uncle, the art collector Cardinal Joseph Fesch – she seems to have gained access to much of the building; in October 1802, Farington found her in a ‘back room … Colouring a print from [a] picture by Titian’.Footnote 37

Proud of the developing venture, Cosway advertised it widely, even sending a prospectus to Thomas Jefferson while he was President of the United States. Cosway and Jefferson had maintained a correspondence since 1786, when they had met in Paris.Footnote 38 In February 1802, she briefly reminisced about their time together before directly pitching her project, describing it in detail:

I am now in the place which brings me to mind every day our first interview, the pleasing days we pass’d together. I send you the prospectus of a work which is the most interesting ever published as every body will have in their possession the exact distribution of this wonderfull [sic] gallery. The history of every picture will also be very curious as we have collected in one spot the finest works of art which were spread all over Italy. – I hope you will make it known among your friends who may like to know of such a work. This will keep me here two years at least & every body seem very Much delighted with this interprise [sic].Footnote 39

Jefferson responded the following January, apologising for the delay and subscribing to the work; he kept the prospectus, which remains among his surviving papers.Footnote 40 As this exchange alone attests, with the Gallery Cosway conceptualized, marketed, and executed works for commercial sale in a way that she repeatedly expressed she could not with oil on canvas. Perhaps as a result, she became quite invested in the project. When financial strains arose with Griffiths, she chose not to abandon the prints, telling Farington that ‘it was like advising a person to part with her favorite Child’.Footnote 41

Cosway had stopped etching the Louvre plates by 1803, when hostilities resumed between Britain and France. From 1803 to 1809, she worked to establish a school for ‘young Ladies’ in Lyon under Fesch’s patronage.Footnote 42 She would increasingly devote her life to education, soon establishing another girls’ school in Lodi, Italy, where she predominantly worked and lived until her death. However, she also contributed to a final print series with Ackermann, a publication that incorporated three women’s advanced reputations in the arts: The Winter’s Day Delineated (1803).

The Winter’s Day Delineated comprised sixteen pages: a four-page introduction by Ackermann and twelve engraved plates after drawings by Cosway, arranged in didactic pairs and each, again, with a descriptive verse underneath. This time, the verses were by a known female author, Mary ‘Perdita’ Robinson (1757–1800), a former actress and mistress to the Prince of Wales who had worked as a poet, editor, novelist, and essayist to sustain an income since 1783.Footnote 43 The illustrations were etched with aquatint by another female artist, Caroline Watson (1761–1814), the official engraver to Queen Charlotte since 1785.Footnote 44 Robinson was an advocate of women’s education, literary abilities, and right to leave their husbands, and had vocally supported the French Revolution’s democratising ideals; her many publications included, in 1799, the Thoughts on the Condition of Women and on the Injustice of Mental Subordination, which engaged with many of the arguments for female education put forth in Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman seven years prior. In fact, Robinson and the late Wollstonecraft had jointly incurred the wrath of Richard Polwhele in his Unsex’d Females, a Poem (1798), alongside Angelika Kauffmann, for their alleged boldness in matters public and private.

Work on The Winter’s Day Delineated began as early as January 1800, when Robinson published an initial four-stanza version of the eventual twelve-stanza poem in The Morning Post, a popular London periodical for which she was the poetry editor.Footnote 45 It is likely that she and Cosway had long been acquaintances, if not friends. They had moved in similar social circles for nearly two decades, and Richard Cosway painted Robinson’s portrait at least nine times.Footnote 46 Whatever their relationship, their collaboration advanced swiftly. By May of that year, The Morning Post updated its readers that ‘the charming pencil of Mrs. Cosway’ was undertaking ‘a flattering tribute’ to Robinson’s poem.Footnote 47 By September, Cosway had nearly finished her designs; as Robinson happily wrote to a friend, ‘I have this morning received a most flattering letter from Mrs. Cosway. She is finishing a series of drawings from some poetical trifles of mine, and they are to be splendidly engraved next winter.’Footnote 48

That winter did not go as planned. Robinson passed away in December 1800 after enduring years of poor health, and as we know Cosway soon crossed the English Channel. Still, when Ackermann finally released the publication three years later, Robinson’s moralizing and protofeminist message remained forceful and clear. As Ackermann explained in his lengthy preface, ‘The intention of the designs is to contrast the accumulated evils of poverty with the ostentatious enjoyments of opulence, thus exhibiting a picture of the state of society as it is’; he guided readers, ‘The series must be considered as combined in pairs, each print forming a striking antithesis to its companion’.Footnote 49 The twelve elaborate engravings by Watson do just that, vivifying Cosway’s drawings and Robinson’s verse by imagining two contrasting visions of a woman’s life based on the social situation into which she was born – one to privilege (‘mansions rich and gay’, in Robinson’s words) and inclined to increasing excess, another to poverty (‘the bleak and barren health, / Where Misery feels the shaft of death’).Footnote 50 As has been noted, this contrasting subject matter led Cosway, quite unusually for an artist of the time, to include depictions of rural poverty as well as the interior of a prison.Footnote 51

Cosway’s compositions throughout the series are rife with social commentary, alternately vibrant and melancholic as they illuminate the implicit and explicit confines that delimited women’s lives across social strata. We see an upper-class woman beginning her day in luxury, a poor family at work in a dilapidating cottage, a ballroom, a jail cell, a dinner party, and a starving mother, unable to feed her infant child. Yet after eight such figurative scenes, Cosway ends on an allegorical note. The penultimate pairing contrasts a group of fashionable women at a milliner’s shop (Plate 9) with a lone figure of genius (Plate 10). In the final pairing, Cosway takes this discrepancy further. On Plate 11, a privileged group of women and men crowd around two gaming tables, gambling and playing chess. On Plate 12, a drained and wearied female figure of Hope drapes herself across a broken anchor, sprawling beside a sinuous, winged male Virtue (Figure 2.1). This Virtue, with his head bowed, is (the text tells us) ‘oppress’d’ by Pride – represented here by a massive, regnant peacock. In Cosway’s striking image, we see her sublime style in its full force, the visual penchant that had earned notice for decades and which Ackermann directly discussed in his prelude:

Mrs. Cosway’s designs, it must be admitted, are sometimes eccentric, but it is the eccentricity of genius, and we have seen instances where she has ‘snatch’d a grace beyond the reach of art’.Footnote 52

He also noted the late Robinson’s ‘genius’, as attested by the popularity of her works.Footnote 53 While scholars have found that the concept of ‘genius’ was increasingly being gendered male at this time – as in the figure by Cosway herself – Cosway and Robinson were two of many female artists and writers to earn its appellation in manuscript and print.Footnote 54 Both of their names feature beneath this final image alongside Watson’s, as they do on every plate in the series, reading from left to right: ‘M. Cosway delt.’, ‘the Poetry by Mrs. Robinson’, ‘Miss C. Watson sculpt.’. Here echoing the arresting figures of Hope, Virtue, and Pride, the three women are likewise united in artistry and cultural contemplation.

Figure 2.1 Caroline Watson, after Maria Cosway, Plate 12, from Mary Robinson, The Winter’s Day Delineated, 1803.

Maria Cosway’s engagement with print remains an overlooked element of a highly public career, of women’s engagement with the arts in the Revolutionary era, and of the enterprising paths they paved to professionalisation. After decades of exhibiting widely recognised and celebrated narrative and portrait works, when she felt she was not ‘permitted to paint professionally’, Cosway actively turned to a didactic, commercial form of print. From an art instruction manual with her husband, she went on to visualize three works commenting on women’s obstacles and opportunities at the time, as well as an arguable history of art. In the process, Cosway encouraged her readers to question the practices and constrictions of the very society in which she had forged her own career. These published series allow us – indeed, impel us – to begin to reevaluate the depths of the social and artistic roles Cosway herself explored, and the ways in which she perhaps did pursue art as a ‘profession’. Cosway certainly knew that her life had been both lengthy and sweeping. ‘Short as Mr. C. memoirs may be’, she mused to her nephew, ‘mine would be perhaps too long, but very full of interesting Matters’.Footnote 55

Caroline Watson (1760/61–1814) has been singled out by David Alexander as ‘the first British woman professional engraver’ with an extended independent career.Footnote 1 In terms of her well-documented oeuvre, lifetime fame, and professional and financial success as a stipple engraver, she is an outlier. Women printmakers rarely signed their prints so their work often went unacknowledged.Footnote 2 Watson signed her prints and even published a number under her own name (1785–1788), notably the portraits of the Royal Princesses Mary and Sophia after John Hoppner, from Fitzroy Street, where she was living at the time with her barrister brother.Footnote 3 The engraved portrait of Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester, which was dedicated to the Queen, was published on 1 March 1785. Although Watson did not receive any official royal commissions, she was appointed Engraver to the Queen in 1785, and used the honorary title, which added cachet, in signing her prints.Footnote 4 Little is known about Watson’s personal life. After her father’s death in 1790, she lived with her aunt, Elizabeth Judkins. Her professional success and recognition notwithstanding, William Hayley’s obituary acknowledged the constraints of gender noting: ‘Her great modesty prevented her being so well known as her merit deserved.’Footnote 5

Watson is best known for her portrait engravings after such leading artists as Sir Joshua Reynolds, John Hoppner, George Romney, Thomas Gainsborough, and Thomas Lawrence. This chapter focuses on an understudied aspect of her oeuvre – her theatrical prints – which will serve as a lens for reexamining how issues of gender, printmaking hierarchies, and patronage both shaped and circumscribed her exceptional career as a female stipple engraver. The only other contemporary female printmaker (and painter) specialising in stipple in England was Marie Anne Bourlier (active 1801–1824), who engraved portraits of the royal family after William Beechey. Watson’s theatrical prints, which stand out in terms of their scale and narrative complexity are, arguably, her most significant contribution in the arena of printmaking. The four large theatrical subjects she engraved for Robert Edge Pine – Ophelia (from Hamlet), Miranda (from The Tempest), Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia, and Garrick Speaking the Ode – and the two large plates, The Death of Cardinal Beaufort and Ferdinand and Miranda Playing Chess, commissioned for Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, testify to the scope of her ambitions as a printmaker and her technical prowess in graphically translating dramatic multifigure subjects in stipple.

Early Career and Patronage

Watson pursued printmaking under the tutelage of her father, James Watson (c. 1740–1790), a leading mezzotint engraver, though there is no documentation regarding her training in stipple engraving.Footnote 6 Stipple or ‘the dotted manner’, a quicker, less technically demanding engraving process in which tone was added with numerous dots, was adopted in England beginning in the mid-1770s. It was widely employed for reproducing portraits, decorative designs, and small paintings and drawings, and could be printed in colour to resemble a chalk drawing.Footnote 7 Stipple engraving was also financially advantageous because it was faster and more impressions could be pulled without reworking the original plate than with other types of intaglio.Footnote 8 In 1780, Watson produced her first stipple plates, including the frontispiece to a life of Isaac Watts, which was favourably mentioned in the Gentleman’s Magazine.Footnote 9 She received commissions from Robert Edge Pine and especially John Boydell in the early 1780s, which were crucial in launching her career. Over the years Watson worked with various publishers including Robert Cribb, Rudolph Ackermann, and the Italian-born printseller Anthony Molteno, who published some of her prints and sold them at his shop.Footnote 10

Earning a living from printmaking was challenging, especially for women, who often lacked access to specialised technical training and the artistic and commercial networks to produce and market their prints. Besides commissioning prints, leading publishers, like Boydell, published catalogues and purchased stocks of plates and reissued them, as was the case with the plates Watson engraved after Pine. Watson benefited from familial training and support and her father’s extensive artistic network. As the daughter of a prominent printmaker, she had a genteel upbringing and grew up observing her father working on plates at home. Although it is not known why Watson elected to specialise in stipple rather than mezzotint, it was fashionable, less technically demanding and, I suspect, affirmed her artistic independence by differentiating her from her father.

Prints were priced according to the size of the plate, the quality, and amount of work involved.Footnote 11 The elegantly printed advertisement for a portrait of Mary Amelia Cecil, Marchioness of Salisbury, engraved after a miniature by Robert Bowyer (1790), offers an illuminating example of how prints were niche marketed at different price points as prestigious commodities, whose allure was enhanced by distinguished patrons and honorifics.Footnote 12 Published by Bowyer, Miniature Painter to His Majesty, the portrait was engraved by Caroline Watson, Engraver to Her Majesty, and dedicated to Her Royal Highness, the Princess Royal. The delicate stipple engraving, which displays Watson’s technical skill in rendering fine details and tonal contrasts, retains the intimacy of a miniature. Marketed to appeal to members of the nobility, wealthy gentry, and upscale collectors, the advertisement stated that orders could be placed with Mr. Bowyer or Mrs. Ryland for the finest proof impressions at 10s 6d (10 shillings and sixpence), or 6s for regular impressions.

From the outset, Watson was patronised by prominent women, notably Frances Coutts, wife of the first Marquess of Bute, whose portrait she engraved.Footnote 13 Throughout her career, she benefited from female patronage and cultivated a female clientele. In addition to dedicating prints to prominent women including members of the royal family, she collaborated with women artists, such as Catherine Fanshawe, whom she may have instructed in printmaking.Footnote 14 The most noteworthy example of this female-centric approach is the series of twelve aquatint plates Watson made after Maria Cosway, illustrating Mary Robinson’s poem, The Winter’s Day, which was produced by women for a predominantly female audience.Footnote 15 The project, announced in The Morning Post on 20 November 1800, took several years to complete. The prints were published in 1803; the letter press is dated 1804. The Literary Magazine, and American Register enthused, ‘the genius of three ladies, in different departments, are happily and splendidly combined’.Footnote 16

Except for Garrick Speaking the Ode, Watson’s theatrical prints from the early 1780s focus on female characters from Shakespeare and the actress Sarah Siddons (1755–1831), a theatrical sensation and popular female role model, widely admired for her powerful acting and her domestic virtue. Although Watson did not exhibit publicly, her prints circulated fairly widely as frontispieces and individual plates, and were highly regarded.Footnote 17 Her prestigious commissions for Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery affiliated her with the most significant artistic enterprise of the late eighteenth century. In the 1786 prospectus, Watson figured alongside the leading engravers and artists in England. The only other female participant was Angelika Kauffmann, who contributed two paintings.Footnote 18 In examining Watson’s theatrical prints and their significance within her oeuvre, I am particularly interested in scrutinizing how individual agency, gender, patronage, market factors, and technical considerations intersected in moulding her successful career as an independent female printmaker.

Theatrical Subjects from the Early 1780s

Robert Edge Pine (1730–1788) probably became aware of Caroline Watson as a printmaker through her father. Primarily known as a portraitist, Pine exhibited at the Society of Artists (1760–1771), and at the Royal Academy, but harboured history painting ambitions. A political radical who supported the American Revolution, he painted an allegorical picture, America (1778), known through an engraving.Footnote 19 In April 1782, Pine exhibited seven subjects drawn from Shakespeare in the Great Room at Spring Gardens, anticipating Boydell’s multimedia Shakespeare Gallery, launched in 1786. The catalogue that accompanied Pine’s ambitious exhibition included a prospectus for a series of seven large engravings to be published in pairs after his pictures in the chalk manner by the best engravers.Footnote 20 Although Caroline Watson’s name does not appear in the newspaper advertisements, Pine commissioned her to engrave two Shakespeare subjects (Miranda from the Tempest and Ophelia from Hamlet), Garrick Speaking the Ode (intended as the first plate), and Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia, which was added later.Footnote 21 Watson’s collaboration with Pine ended abruptly in 1784 when he departed for Philadelphia. According to Edward Edwards, the exhibition failed to meet Pine’s expectations, and only some of the prints were completed.Footnote 22 Boydell purchased the copperplates from Pine and reissued them under his own name in 1784. Miranda and Ophelia, which feature female protagonists, were dedicated to prominent aristocratic women associated with the Opposition – Ophelia to the Duchess of Norfolk, and Miranda to the Duchess of Devonshire – indicating a concerted effort to market them to a female clientele, as does the inclusion of the print of Siddons in the series.Footnote 23

When she returned triumphantly to Drury Lane Theatre in October 1782, Siddons appeared as Euphrasia in Arthur Murphy’s The Grecian Daughter, which remained one of her most acclaimed tragic roles. Artists including William Hamilton, John Keyse Sherwin, the young Thomas Lawrence, and Pine rushed to depict Siddons in the heroic role.Footnote 24 Siddons posed for Pine in January 1783. His ambitious painting of Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia was a speculative venture intended to capitalise on her celebrity, raise his profile, and promote his art. An advertisement in The Morning Chronicle, and London Advertiser, 18 March 1783, extolled Mr. Pine’s picture and invited readers to view the original at his house in Piccadilly. Pine also proposed having an elegant print engraved from it ‘with the utmost expedition’.Footnote 25 In 1785, Watson engraved Siddons and Kemble in the Characters Tancred and Sigismunda (BM 1931,0509.170) after a miniature by Charles Shirreff, on exhibit at the Royal Academy. The subscription refers to her as ‘Miss Watson, Engraver to her Majesty’, attesting to her name recognition. In April 1785, Shirreff advertised the print for 10s 6d, with subscriptions taken by three other printsellers and her father, James Watson. The print, published by Shirreff on 12 December 1785 (according to the inscription), was advertised in The Morning Post under Boydell’s name in January 1786, with proofs at 10s 6d, and prints at 6 shillings.Footnote 26

Although it’s tempting to posit a direct connection between Siddons and Watson, I have not uncovered any documentary evidence; however, there is an intriguing theatrical connection. Watson engraved Lady Elizabeth Foster’s portrait after John Downman in 1788, one of a set of six oval prints after Downman’s large portrait drawings of fashionable beauties that had served as scenery for the private theatrical production of Arthur Murphy’s The Way to Keep Him at Richmond House in 1787. Siddons’s portrait, which was engraved by P. W. Tomkins, was part of the series which included fashionable aristocratic ladies – the Duchess of Richmond, Lady Elizabeth Foster, Lady Duncannon, and the Duchess of Devonshire – who had attended the performance, as well as Siddons and Elizabeth Farren, attesting to high society’s infatuation with the stage. The prints were marketed both individually and as a set for 36 shillings in black or brown ink, or 3 guineas, printed in colours.Footnote 27

Pine’s commission to engrave the plates depicting Miranda in The Tempest, Act I, Sc. 2, and Ophelia in Hamlet, Act IV, Sc. 5, was an important opportunity for Watson to demonstrate her printmaking abilities. Reproducing a painting as a print was a complex process of translation from one medium to another that required technical skill and artistic interpretation.Footnote 28 With their youthful female protagonists, the subjects were well-suited to the delicacy and finesse of stipple, which was associated with women and fashion. Critics of stipple like John Landseer attacked it as inferior, lacking vigour, and propelled by fashion and degenerate taste.Footnote 29 Relatively large at 38 × 43 cm, the two engravings, though not obviously linked except for their female protagonists and Shakespearean subjects, were marketed as a pair, titled Miranda and Ophelia, respectively, underscoring their feminine focus. Miranda, published by Pine c. 1782, was reissued by Boydell in 1784.Footnote 30 Ophelia, initially published c. 1782–1784, was reissued in the same format on 1 June 1784. The scene from the Tempest depicting Miranda’s excitement at the sight of Ferdinand exhibits a high level of technical skill and a finely modulated tonal range. The scene focuses on the figures of Prospero and, especially, Miranda, whose delicate form and luminous white dress glow against the darker landscape background. The crowded court scene from Hamlet showcases Ophelia, her mind unhinged by her father’s death and Hamlet’s abandonment. Crowned with weeds and wildflowers, she stands at centre stage before the King and Queen, singing and mindlessly distributing herbs, as Laertes weeps at far right. The dramatically illuminated figure of Ophelia flutters like a moth in the shadowy medieval hall. The inconsistencies in scale and anatomical defects are attributable to Pine whose weak drawing was criticised by Edwards.

Imaginary illustrations inspired by Shakespeare, like those of Pine, were grounded in the text, rather than stage performance, and were glossed with quotations. Pine’s paintings anticipate the ambitious cycle of Shakespeare subjects Boydell would commission from leading artists a few years later for his Gallery, which he loftily aligned with the promotion of history painting and British nationalism and endeavoured to distance from the taint of theatre.Footnote 31 From the outset, Boydell faced the problem of securing a sufficient number of expert engravers to rapidly produce large and small prints after the paintings for the subscribers. Line engraving, the most costly and time-consuming intaglio process, was the gold standard for reproductive prints after paintings. Stipple, which was faster and less expensive, was effective for small-scale prints, especially the rendering of delicate detail, but lacked the sharp definition of form and tonal variety of line engraving. The issue of quality as opposed to speed would haunt Boydell and his nephew, Josiah. In their struggle to deliver the quasi-industrial volume of plates for the Shakespeare Gallery in a timely manner, they relied increasingly on mixed techniques and stipple engraving.Footnote 32 Widespread complaints about delays and the declining quality of the plates contributed to the sharp fall-off in subscriptions.Footnote 33

Watson’s large (47.4 × 35.9 cm) engraving of Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia (Figure 3.1) offered a more expansive expressive register to demonstrate her technical and interpretive skill. Not included in the original project, it was presumably added to cash in on Siddons’s celebrity.Footnote 34 Vengefully brandishing a dagger raised over the body of the tyrant, Dionysus, Siddons, directs her gaze toward her aged shackled father. Giving concrete form to the lines from The Grecian Daughter inscribed below, ‘… in a dear Father’s cause, / A Woman’s vengeance tow’rs above her Sex’, Siddons’s lofty figure, forceful pose, and expression of calm fury are strikingly rendered. Overall, the effect is more dynamic and sculptural than the Miranda or Ophelia engravings. Represented in close-up view, her body pivoting in space, Siddons is dramatically illuminated from the upper right. Rather than an invented illustration, Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia is a theatrical portrait based on her emotionally gripping performance in The Grecian Daughter, which contemporaries extolled. Artists including Hamilton, Lawrence, Sherwin, and Pine depicted Siddons in The Grecian Daughter in the early 1780s, and her image was widely disseminated in print form.Footnote 35

Figure 3.1 Caroline Watson, after Robert Edge Pine, Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia, 1784. Stipple engraving, 47.4 × 35.9 cm.

David Alexander considers it one of Watson’s least satisfactory prints, due to Siddons’s lack of frenzied emotion; however, the criticism seems misplaced since she was reproducing Pine’s painting for which the actress had posed.Footnote 36 I contend that Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia should be recognised as one of Watson’s most impressive achievements and that it closely parallels contemporary accounts of her stage performances. Her expression, which combines tenderness with resolve, is subtly transcribed, including her raised eyebrows and powerful gaze. It was widely acknowledged by contemporaries that Siddons’s statuesque poses were influenced by classical sculpture, which she greatly admired and emulated in her own sculptural works.Footnote 37 Her pose in the print closely resembles one of Gilbert Austin’s Seven Attitudes by Mrs. Siddons, illustrated in Chironomia (1806).Footnote 38 Moreover, Pine’s heroic portrayal and Watson’s print after it were doubtless intended to highlight the powerful resolve and fortitude that propelled Euphrasia to slay Dionysus and rescue her father. Like the other prints Pine commissioned from Watson, it was produced in both a plain and a coloured version, printed in red to resemble a chalk drawing. Although Mrs. Siddons as Euphrasia demonstrates Watson’s skill at capturing emotion and translating the drama of the stage in graphic form, she only created one other small-scale theatrical portrait, namely, Siddons and Kemble as Tancred and Sigismunda (1785), discussed earlier in this section.

Watson’s largest stipple, Garrick Speaking the Ode, after Pine, which measures 62.5 × 45.5 cm, was published by Pine on 1 March 1783, and reissued by Boydell on 25 March 1784. Dedicated to Elizabeth Montagu, ‘Queen of the Blue-Stockings’, it was captioned with the concluding verses of the Jubilee Ode. Pine, who had previously painted Garrick’s portrait, bombastically reenvisioned his climactic recitation of the Ode at the 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee, hoping to leverage his posthumous celebrity as the leading interpreter and promoter of Shakespeare.Footnote 39 Although the procession of Shakespeare characters was rained out at Stratford-upon-Avon, it was successfully restaged at Drury Lane. The plate would have posed particular technical challenges due to its ambitious scale, over-the-top subject, idiosyncratic cast of characters, and otherworldly incandescent lighting. The gesticulating figure of Garrick, declaiming the ‘Ode to Shakespeare’ and apotheosising the bard’s statue, is the only solid element in the murky otherworldly mishmash of Shakespearean characters. To the left of the statue, the Tragic Muse, King Lear, and Cordelia’s lifeless body are represented, with Hecate revealing the bloody dagger to Macbeth in the background. At the right, the Comic Muse, Falstaff, Prospero, Caliban, and Ariel are pictured.Footnote 40 The 1782 pamphlet described the cast of characters as, ‘all uniting to express the extensive luxurious imagination of the Great Author’.Footnote 41 The motley cast and conceptual incoherence of the composition should be laid at the feet of its creator, Pine, rather than Watson. In Shakespeare Sacrificed: – or the Offering to Avarice (1789), James Gillray maliciously deconstructed Pine’s hyperbolic homage, replacing the figure of Garrick with Boydell – the destroyer and commercial exploiter of Shakespeare.

The Boydell Commissions

The only comparably ambitious theatrical prints Watson would produce were the two large plates commissioned for Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, The Death of Cardinal Beaufort from Henry VI, Pt. II, Act III, Sc. 3, after Reynolds, first state (1790); second state (1792), and Ferdinand and Miranda Playing Chess from The Tempest, Act V, Sc. 1 (1795), after Francis Wheatley, both 57.4 × 40.7 cm. Watson was paid £210 for each print, a standard rate at the lower end of the remuneration scale, but double what Wheatley received – a mere £105.Footnote 42 The commission for the Death of Cardinal Beaufort was due to Reynolds’s insistence that Watson engrave his painting. She engraved numerous portraits after Reynolds, including his Self-Portrait (c. 1788) wearing spectacles, widely considered the best print of Reynolds.Footnote 43 Boydell, who commissioned numerous prints from Watson, was aware of her technical skill and previous experience engraving subjects from Shakespeare. The intimate genre-like depiction of Miranda and Ferdinand playing chess after Wheatley showcases Watson’s delicate stippling and subtle modelling of the illuminated figures, which glow against the dark background of the cave, demonstrating her mastery of lighting and tonal effects.Footnote 44

The task of engraving Death of Cardinal Beaufort, which garnered mixed reviews when it was exhibited at the Shakespeare Gallery in 1789, proved challenging on artistic as well as technical grounds. Reynolds, who never profited from engravings after his own pictures, was initially reluctant to participate in Boydell’s speculative venture. According to James Northcote, Reynolds considered it degrading to paint for a printseller.Footnote 45 Since Henry VI was not mounted on the London stage during Reynolds’s lifetime, the picture had no direct theatrical connection. The close-up depiction of the dying cardinal, which was based on an earlier oil sketch, was exhibited at the Shakespeare Gallery in 1789, where its resemblance to Nicolas Poussin’s well-known Death of Germanicus was noted in the press.Footnote 46 According to William Mason, Reynolds’s model for the Cardinal was an elderly porter or coal heaver, who posed grinning in the throes of death.Footnote 47 The controversial fiend (which was a figure of speech) behind the dying cardinal was widely criticised and ridiculed. In The Bee, Humphry Repton complained that the fiend was beneath the dignity of the subject and the artist and did not figure in Shakespeare’s dramatis personae.Footnote 48 However, Reynolds stubbornly refused to remove the troublesome fiend, even at Edmund Burke’s urging. In the first state of the print, dated 25 March 1790, as in the painting, the fiend is clearly visible behind the Cardinal’s head. Following Reynolds’s death, presumably at Boydell’s instigation, the fiend was removed from the painting and the engraving. In the final state, dated 1 August 1792, the fiend was laboriously scraped out, but faint vestiges remained on the plate.Footnote 49 The murky bedside scene, with its dramatic chiaroscuro effect evokes mezzotint, which was often used for reproducing Reynolds’s paintings, though Watson used stipple and etching. The caricatural quality of the heads, especially the cardinal’s grotesque grimace and clawing hand in the painting were faithfully transcribed in Watson’s print.Footnote 50 The fiend and grimacing cardinal are emblematic of the pitfalls of attempting to translate Shakespeare’s text too literally in visual form, even for an artist as gifted as Reynolds.Footnote 51

Watson’s Legacy