Climate finance is a hotly disputed topic, the contestation over what it means adding to the controversy. While the term is sometimes used to refer to all financial flows that influence climate mitigation or adaptation/resilience, in the context of this book, I focus on financial flows from developed to developing countries ‘whose expected effect is to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions and/or to enhance resilience to the impacts of climate variability and the projected climate change’ (Reference Gupta, Harnisch, Barua, Edenhofer, Pichs-Madruga and SokonaGupta et al., 2014, p. 1212). Thus, flows within countries, to developed countries and among developing countries are not included in the discussion. Yet, public climate finance, which unlike fossil fuel subsidy reform constitutes fiscal expenditure, is included.

Climate finance has been addressed within and outside the climate regime complex since the 1992 Rio Conference on Environment and Development. Simultaneously, increasing amounts (though small compared to estimated needs) of climate finance have been delivered from developed countries. The governance of climate finance straddles the international and the domestic levels, the latter including the developed countries which are supposed to deliver it and the developing countries in which it is spent. Furthermore, as an issue that involves both climate change and economic issues, it also straddles economic and environmental (as well as development) institutions and actors at both the international and domestic levels. The name highlights this duality: the purpose is to address climate change (an environmental issue), but the way of achieving this purpose is to use finance (an economic instrument). Hence, it is unsurprising that climate finance is the issue in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) climate negotiations that finance ministries are most involved with (Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b).

Although climate finance has been part of the climate regime complex since its inception (Pickering, Skovgaard, et al., 2015) in 1992, this book focuses on the discussions from the run-up to the 2009 Fifteenth Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP15) in Copenhagen to the 2015 Twenty-first Conference of the Parties in Paris. The UNFCCC, adopted at 1992 Rio Conference, stipulates how developed countries shall ‘provide new and additional financial resources’ to meet the ‘costs incurred by developing country Parties in complying with their obligations under the Convention’ (UNFCCC, 1992: 4(3)). It also requires that such finance shall be provided in accordance with the principle of ‘Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities’ (UNFCCC, 1992: 4(2)). A key dividing line in the negotiations and in the international debates about climate finance has been that between developed and developing countries. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s Annex II stipulates which countries shall provide climate finance (essentially the countries which were OECD members in 1992), and within the UNFCCC negotiations these countries have been the ones defined as developed countries (UNFCCC, 1992). Developing countries are according to the Convention defined as non-Annex I countries; Annex I countries consisting of the Annex II countries plus economies in transition, i.e. post-communist countries.

The other Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) adopted in Rio (the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification) contain similar provisions, and in the decade following Rio, climate finance was mainly treated as a subtype of the ‘environmental finance’ provided under these MEAs (Reference Keohane and LevyKeohane and Levy, 1996). Actual climate finance flows remained modest during this period (Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2011b). Yet, developing countries progressively raised climate finance as an issue in the UNFCCC negotiations, and development finance institutions including the multilateral development banks (MDBs) and the OECD Development Assistance Committee increasingly addressed the provision of climate finance. Within the UNFCCC, the culmination came with the adoption of the USD 100 billion target at the 2009 Fifteenth Conference of the Parties in Copenhagen to the UNFCCC (COP15). The USD 100 billion target is often described as one of the few successes of COP15 (Reference Gomez-EcheverriGomez-Echeverri, 2013). Developed countries committed to ‘mobilizing jointly USD 100 billion dollars a year by 2020 … from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources of finance’ (UNFCCC, 1992: para 8). These provisions opened up for subsequent contestation regarding what sources should count towards the target and how (see Section 9.1). The Copenhagen Accord was also the first decision to mention the Green Climate FundFootnote 1, which was formally established the following year at the Sixteenth Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in Cancún (COP16).

Since 2009, climate finance flows have increased, although it is greatly disputed whether they are meeting the USD 100 billion target (OECD, 2019b; Reference Roberts and WeikmansRoberts and Weikmans, 2017). At the 2015 Twenty-first Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in Paris (COP21), the Parties agreed to set a new, higher collective financing goal before 2025 (UNFCCC 2015: para. 53) and did not solve the definitional issues. Subsequent negotiations have focused on what flows of finance should count towards the USD 100 billion target, scaling up climate finance both before and after 2020, the balance between mitigation and adaptation finance and the role of public and private finance. At the same time, most climate finance has flowed outside the UNFCCC and the other UN institutions in which developing countries yield significant influence (CPI, 2019). Rather, most of the flows have been determined by public and private actors in developed countries and by MDBs. A persistent feature of climate finance flows has been that mitigation receives the bulk of (particularly private but also public) finance and that – depending on the definition – private finance is several times larger than public (CPI, 2019).

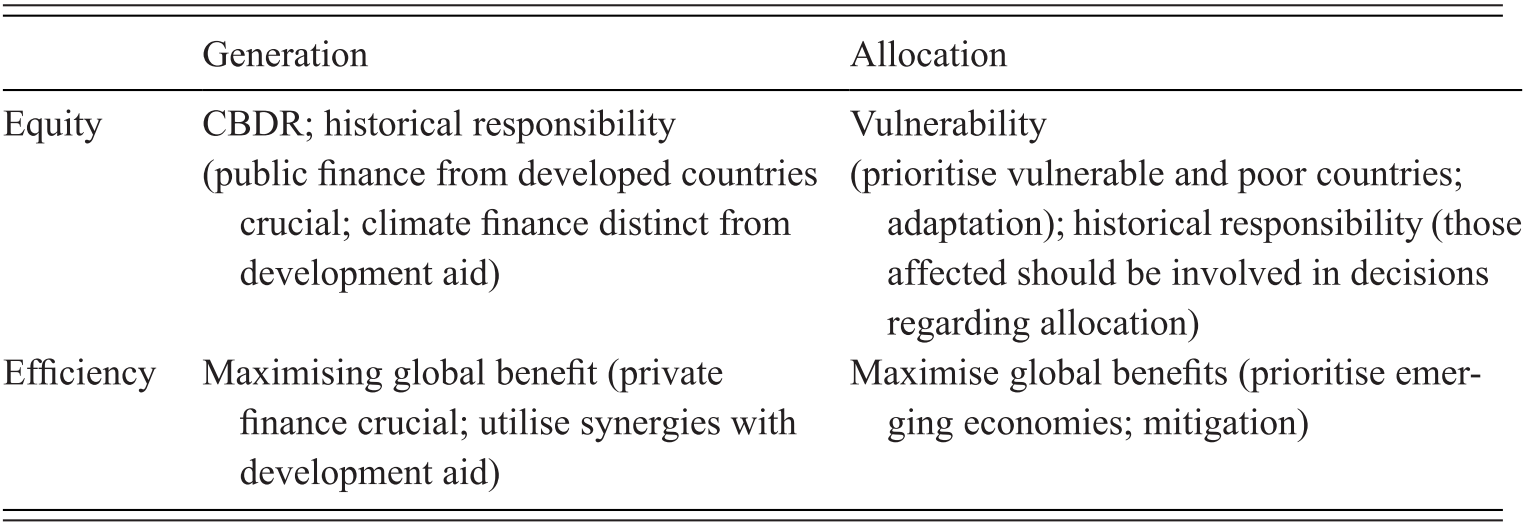

This chapter proceeds with an outline of the cognitive debate regarding what kinds of financial flows can be defined as climate finance, followed by a discussion of the key normative issues of contestation in climate finance discussions. The following section focuses on equity versus efficiency regarding the generation and allocation of climate finance. Finally, the most important groups of actors (beyond the three international economic institutions) and their roles in climate finance are discussed.

9.1 What Financial Flows Constitute Climate Finance?

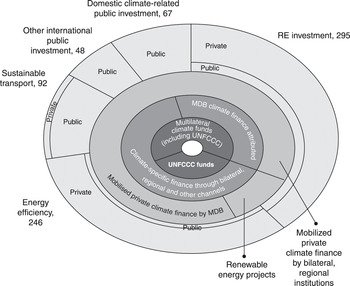

The framing of particular flows of finance as climate finance constitutes an important cognitive aspect of climate finance. While other cognitive aspects may also be relevant, the question of what flows of finance count as climate finance is the single most important question involving cognitive ideas and climate finance. This question has been strongly contested even before the USD 100 billion target, including whether and under which conditions private finance and development aidFootnote 2 can be considered climate finance. Defining the target as USD 100 billion mobilised by developed countries without specifying what ‘mobilised’ meant added to the uncertainty. To gain an understanding of the different kinds of finance that are sometimes framed as climate finance and sometimes not, the UNFCCC Standing Committee’s so-called ‘onion diagram’ is instructive (see Figure 9.1). This diagram places different kinds of climate finance in concentric circles: the more undisputed their character as climate finance is, the closer they are to the centre; the larger the flow, the larger the circle. At the very centre is the funding provided by designated multilateral climate funds. These include the UNFCCC climate funds (the Green Climate Fund and other Funds operating under the UNFCCC such as the Adaptation Fund), in 2015 and 2016 disbursing about USD 600–1,600 million annually, as well as other multilateral climate funds such as the Climate Investment Funds (anchored within the World Bank), funds which in 2015–16 amounted to USD 1,400–2,400 million annually (UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance, 2018). Some observers argue that only such finance can be counted as climate finance (Reference DasguptaDasgupta and Climate Finance Unit, 2015).

Figure 9.1 The concentric circles of climate finance. All numbers refer to the size of flows measured in USD billions.

The second layer consists of public finance flowing through channels not designated as climate institutions: MDB climate finance not stemming from climate funds and public finance from developed countries flowing through bilateral, regional and other non-MDB channels.Footnote 3 According to the Standing Committee (2018), the former amounts to USD 17–20 billion annually, the latter to around USD 30 billion. Of these two kinds of finance, the latter has proven most controversial (Reference Roberts and WeikmansRoberts and Weikmans, 2017). It consists of bilateral Official Development Assistance (ODA), provided by developed countries marked as mitigation or adaptation-related by the country itself in its Bi-Annual Reports to the UNFCCC. Because it is up to the individual contributor country to identify its own projects as climate-related, climate-related ODA is often overcoded in the sense that the climate objectives are overstated (Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2011b; Reference Weikmans, Roberts, Baum, Bustos and DurandWeikmans et al., 2017). Yet, the controversy regarding treating ODA as climate finance stems not only from overcoding but also from the provision already stipulated in the UNFCCC Convention that climate finance should be ‘new and additional’ to ODA (see discussion in Section 9.2.1).

The third layer consists of private finance for activities addressing climate change mobilised by the MDBs and by regional and bilateral institutions as well as renewable energy projects, in total amounting to around USD 15–17 billion annually in 2015–16, the bulk mobilised by MDBs. These flows differ from the inner layers in stemming from private sources, and from outer layers in being mobilised by public finance from developed countries, for example, an MDB providing guarantees or taking on parts of the risk associated with loans for climate projects.

The fourth layer covers all the flows that do not flow from developed to developing countries, including public and private finance spent within countries and between developed countries as well as between developing countries, so-called South–South finance (and are hence beyond the main focus of this part of the book). This layer was estimated at around USD 680 billion annually in 2015–16, although the difficulties in collecting reliable data are greater here than in the inner layers (UNFCCC SCF 2018). Some observers have argued that there de facto is a fifth layer of climate finance, namely the finance flowing to activities with a negative climate impact, such as fossil fuel extraction and consumption (e.g. coal-fired power plants, aviation), unsustainable logging, steel and cement production, and so forth (Reference Paul, Caroline, Joe, Laetitia and BiankaPaul et al., 2017; Reference Whitley, Thwaites, Wright and OttWhitley et al., 2018). Such finance is often referred to as brown finance as opposed to the green finance constituting the finance identified by the Standing Committee on Finance (SCF) (CPI 2018; Climate Transparency 2018), and also includes fossil fuel subsidies discussed in Part II of the book. While such brown flows are undisputedly several times greater than the green ones, they remain outside of the focus of this part of the book.

The preceding discussion concerns the question of the sources of finance that can be considered climate finance, yet the question of which kinds of finance (grants, guarantees, loans, equity) can be considered climate finance has also loomed large. While there is consensus that grants may count as climate finance, whether and how loans should be counted as climate finance is more disputed. Given that the vast majority of climate finance (including the two inner layers of the onion diagram) is provided as loans or equity, this is important (CPI, 2019). Even public finance constitutes predominantly loans, the MDBs almost solely providing loans. Many of the public loans are provided on more favourable terms than those that could finance a project if they were obtained in the financial market, for example, the interest rate is lower or the loan period longer (what is known as a concessional loan). Equity, where financing comes from ownership rather than loans, is mainly private finance.Footnote 4 A key issue is how to calculate the value of especially loans but also equity. As regards the USD 100 billion target, to many it seems counterproductive and unfair to equate USD 1 million provided as a grant with USD 1 million provided as a loan that has to be repaid with interest. One solution has been to calculate the ‘grant equivalent’ of a concessional loan, i.e. the difference between the value of a loan obtained in the market and the actual value of the loan (value calculated as the sum of future repayments and interests, Reference ScottScott, 2017). Likewise, there is consensus within the UNFCCC that only private finance caused or leveraged by public finance should count towards the USD 100 billion target. In both cases, there has been much technical debate regarding how to carry out the calculations.

9.2 Contested Issues in Climate Finance

Besides the cognitive dimension discussed earlier, contestation over important normative issues have also characterised climate finance (Reference Dellink, den Elzen, Aiking, Bergsma, Berkhout, Dekker and GuptaDellink et al., 2009; Reference Pickering, Betzold and SkovgaardPickering et al., 2017; Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b). This includes purely legal norms such as ‘Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities’ (CBDR) that have drawn much attention (Reference Brunnée and StreckBrunnée and Streck, 2013; Reference JinnahJinnah, 2017), as well as less explicitly legally defined normative ideas such as efficiency and equity. Efficiency and equity have been key themes in international climate finance politics, as discussed in the two following subsections. This book will focus on two key issues regarding the different normative ideas that have emerged in climate finance governance, and which are particularly pertinent to international economic institutions:

1. Generating resources: Which normative ideas should guide the generation of climate finance?

2. Allocating resources: Which normative ideas should guide the allocation of climate finance?

9.2.1 Generating Resources

Regarding the generation of resources, as mentioned at COP15, close to all countries agreed on a USD 100 billion target for 2020 as well as a fast-start finance target of USD 30 billion in 2010–12. Developing countries had in the preceding negotiations proposed a target of 1–1.5 per cent of developed countries’ GDP, while several developed countries were opposed to any targets at all, although not to providing climate finance in itself (Reference Bailer and WeilerBailer and Weiler, 2015). Subsequently, in the Paris Agreement it was agreed that this goal shall continue through 2025 but that prior to 2025 a new goal shall be set from a floor of USD 100 billion (UNFCCC, 2015). Two kinds of normative ideas, focusing on equity and efficiency respectively, have been central to the discussions of the sources that may count towards the USD 100 billion target. On the one hand, equity-oriented normative ideas, among which CBDR (enshrined in the UNFCCC) constitutes an important norm, and implies that developed countries take on a greater burden than developing countries due to their higher level of development, and arguably provide all the climate finance. Another important equity norm, historical responsibility, recommends that countries contribute to the global effort against climate change, including climate finance, according to how much they have emitted historically, thus placing a significant burden on developed countries (Reference Persson and RemlingPersson and Remling, 2014). On the other hand, efficiency (or cost-effectiveness) concerns generating climate finance in a way that provides the maximum benefit for a given level of climate finance resources (Reference Stadelmann, Persson, Ratajczak-Juszko and MichaelowaStadelmann et al., 2014). Importantly, efficiency as a normative idea entails an emphasis on the economic costs and benefits of climate finance, which fits in with the worldviews of the economic institutions. Aiming to maximise benefits at the global level is a key tenet of much environmental economics literature, whereas national governments have often sought to maximise the national benefits from the climate finance they provide (Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b). A third notion, effectiveness or focusing on the degree to which a measure is effective in mitigating or adapting to climate change irrespective of economic costs or equity concerns, has been contested in international climate finance discussions, since all actors agree that climate finance should be effective.

These normative ideas have repercussions for how the USD 100 billion target should be met. First, regarding public finance, key issues have been whether to adopt a burden-sharing key based on GDP or emissions determining the individual country contributions and whether emerging economies are obliged to provide climate finance. Several developing countries and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have used CBDR and historical responsibility to argue in favour of the former and (in the case of emerging economies) used CBDR to argue against the latter. Developing countries do not always agree on these issues, for instance China has been sceptical of historical responsibility, whereas Least Developed Countries advocated softening the sharp distinction between developed and developing countries regarding climate finance by encouraging the latter (especially emerging economies) to also contribute such finance (Least Developed Countries’ Group, 2014). The United States (including the Obama administration) has been against burden-sharing and strongly in favour of contributions from developing countries, while the EU has been in favour of both. In the end, no burden-sharing key has been adopted, while in the Paris Agreement, developing countries are encouraged to provide or continue to provide climate finance voluntarily (UNFCCC, 2015: Article 9.2).

The normative ideas have also been salient regarding the relationship between public climate finance and development aid, particularly the norm that climate finance should be new and additional to ODA. Already before Rio, developing countries worried that environmental finance would be taken from existing ODA. Accordingly they (successfully) insisted on provisions that environmental finance should be new and additional to the existing commitment of developed countries to provide 0.7 per cent of Gross National Income in development aid, a commitment few of them have met (Reference Roberts and WeikmansRoberts and Weikmans, 2017; Reference Stadelmann, Roberts and MichaelowaStadelmann et al., 2011). According to several developing countries, only when a country has met its target of 0.7 per cent ODA can finance above that level be considered climate finance. Yet, the Paris Agreement does not entail the provision that climate finance should be new and additional (UNFCCC, 2015), and in general the post-Paris UNFCCC climate finance discussions have focused more on other issues than whether climate finance is additional to the 0.7 per cent ODA target.

Efficiency, more specifically the complementarities between addressing climate change and promoting development, has been key to the arguments of developed countries and development banks for an integrated approach to climate finance and development aid (Reference Bailer and WeilerBailer and Weiler, 2015). Yet, developing countries and NGOs argue that the two kinds of finance are fundamentally different since public climate finance is based on developed countries’ historical responsibility and CBDR, whereas development aid is based on the responsibility of the wealthy to assist the poor (Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2011b). Consequently, climate finance should be delivered in a way that reflects developing countries’ ‘entitlement’ to funds, that is, with minimal conditions attached and as grants rather than loans (Reference Ciplet, Roberts and KhanCiplet et al., 2013; Reference MooreMoore, 2012). This discussion of the relationship between public climate finance and development aid also concerns the fundamental question of who gets to decide the allocation of climate finance (see Section 9.2.2), since treating it as development aid means that the decisions over how climate finance is spent are de facto left to the individual contributor countries (and to multilateral development institutions such as the MDBs).

Regarding private finance, developed countries as well as development banks have argued that private finance is key to an efficient response to climate change. Most developing countries do not disagree with the importance of private finance, but prefer targets solely for public finance to keep developed countries to their (equity-based) obligations, and fear that including private finance under targets will erode the obligations of developed countries. Other sources discussed include so-called innovative or alternative sources (e.g. levies on international aviation), which have been less popular among states due to concerns over relinquishing sovereign control over taxation, but popular among non-state actors for both equity and efficiency-based reasons (see inter alia Reference Stadelmann, Michaelowa and RobertsStadelmann et al., 2013).

More recently, the discussions of climate finance have become intertwined with discussions of investment and greening private financial flows (Reference Campiglio, Dafermos, Monnin, Ryan-Collins, Schotten and TanakaCampiglio et al., 2018; Reference Hong, Karolyi and ScheinkmanHong et al., 2020). In this way, the emphasis is shifting towards making financial flows consistent with climate (and other sustainability) objectives, including ensuring that there is sufficient private investment in renewable energy, energy efficiency, the building of infrastructure that is resilient to climate change and so forth. These more technical discussions rarely address equity issues.

9.2.2 Allocating Climate Finance

The normative ideas guiding the allocation of climate finance concern principles for allocating climate finance between countries as well as between mitigation and adaptation and involve efficiency and equity-oriented normative ideas such as vulnerability. The principle of vulnerability entails prioritising adaptation finance over mitigation finance and the most vulnerable countries over the ones that provide most adaptation for the money (Reference MooreMoore, 2012). Efficiency in the context of climate finance allocation refers to the ‘allocation of public resources such that net social benefits are maximised’ (Reference Persson and RemlingPersson and Remling, 2014, p. 489; see also Reference GrassoGrasso, 2007; Reference Stadelmann, Persson, Ratajczak-Juszko and MichaelowaStadelmann et al., 2014). Thus, efficient climate finance is spent where it provides most mitigation or adaption for the money, which at least in the case of mitigation means emerging economies rather than Least Developed Countries (Reference Fridahl, Hagemann, Röser and AmarsFridahl et al., 2015).

Adaptation and mitigation finance differ in that mitigation constitutes a global public good which it is in the interest of developed countries to contribute to independently of where it takes place, whereas adaptation in developing countries only has indirect benefits to developed countriesFootnote 5 (Reference Ciplet, Roberts and KhanCiplet et al., 2013; Reference Persson and RemlingPersson and Remling, 2014). Adopting a global efficiency perspective, mitigation finance is Pareto-improving due to the lower mitigation costs in developing countries, while adaptation finance is not (Reference RübbelkeRübbelke, 2011). Consequently, arguments in favour of adaptation are based on vulnerability and historical responsibility norms, unlike mitigation which can be argued for in terms of efficiency and effectiveness. Several developing countries – particularly Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States – have called for an even split between mitigation and adaptation finance, while developed countries generally have been more interested in contributing mitigation finance (Reference RübbelkeRübbelke, 2011).

Table 9.1 Overview of key climate finance norms and the resulting positions on issues (in brackets)

| Generation | Allocation | |

|---|---|---|

| Equity | CBDR; historical responsibility (public finance from developed countries crucial; climate finance distinct from development aid) | Vulnerability (prioritise vulnerable and poor countries; adaptation); historical responsibility (those affected should be involved in decisions regarding allocation) |

| Efficiency | Maximising global benefit (private finance crucial; utilise synergies with development aid) | Maximise global benefits (prioritise emerging economies; mitigation) |

On a more overarching level, equity and efficiency in the allocation of climate finance also concerns the question of who determines the allocation (Reference Duus-OtterströmDuus-Otterström, 2016). If public climate finance is treated in equity terms as constituting a solution to developed countries’ historical responsibility, those affected, particularly developing countries, should have a say in how it is allocated. If it is treated as a subtype of development aid, decisions regarding its allocation are de facto left to the contributors (see Section 9.2.1). Hence, efficiency in itself does not lead to specific conclusions regarding who should determine the allocation of climate finance, but may lend itself to arguments for utilising synergies with development aid and economies of scale and avoid building costly new governance structures, de facto favouring developed countries.

9.3 The Climate Finance System and Its Main Components

At the international level, besides the normative fragmentation outlined earlier, the climate finance system is also characterised by considerable institutional fragmentation, with a range of institutions addressing the issue (Reference Pickering, Betzold and SkovgaardPickering et al., 2017). These institutions include UN and non-UN, environmental and non-environmental, public and private institutions.

9.3.1 The UNFCCC

The most important international institution for the governance of climate finance is the UNFCCC (Reference Pickering, Betzold and SkovgaardPickering et al., 2017). As discussed earlier, it was the origin of the USD 100 billion target and has been instrumental in institutionalising norms such as CBDR. Yet, the vast majority of the decisions regarding how much to contribute and how to allocate climate finance are reached outside the UNFCCC, in governments of developed countries, MDB headquarters and as regards private finance, corporate headquarters (Pickering, Jotzo, et al., 2015). Hence, the UNFCCC institutions have not played the role that most developing countries would have liked it to play, and often argued in favour of in the climate finance negotiations. The Green Climate Fund (GCF), Adaptation Fund, Least Developed Countries Fund, the Strategic Climate Change Fund and to some degree the Global Environment Facility (GEF)Footnote 6 operate under the UNFCCC, and allocated USD 0.6–1.6 billion during the period 2015–16 (the vast majority by the GCF). These funds have their own boards, but the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties provides them with guidance and directions. Despite the GCF increasing its volume of finance, the UNFCCC funds only disburse a small share of the total of public climate finance and have been plagued by internal disagreement and by the Trump administration’s unwillingness to contribute to them. The UNFCCC’s most important role has been to guide climate finance through the introduction and institutionalisation of norms (e.g. CBDR), targets (the USD 100 billion target). The SCF, a climate finance institution under the UNFCCC, has also played an important role in providing knowledge about climate finance, especially estimates of flows, as well as guidance to the Funds under the UNFCCC.

Decision-making within the UNFCCC takes place on the basis of consensus, which de facto grants developing countries considerable leverage compared to the institutions studied here or the MDBs, in which developed countries have the greatest influence. Unsurprisingly, developing countries have often pushed to have the majority or at least a larger share of climate finance flowing through UNFCCC funds, and greater UNFCCC influence over non-UNFCCC climate finance. Such influence has taken the shape of clearly defined guidelines concerning what constitutes climate finance and how it should be allocated, for instance prioritising Least Developed Countries, adaptation and other priorities that may be downplayed by developed countries (UNFCCC, 2015).

9.3.2 Other UN Institutions

UN institutions beyond the UNFCCC have mainly been important as implementers of climate finance projects, for example, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Environment Programme (UNEP). Similarly to the UNFCCC, developing countries have significant influence within these institutions. Among the non-UNFCCC UN initiatives, the most important one has been the High-level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing (AGF), which was established in 2010 by UN Secretary Ban Ki-Moon to draft a report on the sources of climate finance, including various public, private and so-called innovative or alternative sources, for example, levies on international aviation (United Nations, 2010). This report provided a range of different ideas and possible solutions, which were utilised in climate finance discussions during the subsequent years. More recently, several other UN institutions have also been active in producing knowledge, notably the UNEP Finance Initiative, a partnership between UNEP and the global financial sector. This partnership aims to create principles for what qualifies as sustainable investment and to disseminate knowledge about such investment among public and private stakeholders (United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, 2020).

9.3.3 The World Bank

The World Bank is another central institution in the governance of climate finance. Developed countries have been more in favour of granting the Bank a more important role than developing countries have been, because of the former group’s significant influence within the Bank (votes are allocated on the basis of financial contributions and GDP) and its worldview being closer to the positions of developed countries than to developing ones (Reference SchalatekSchalatek, 2012). The World Bank’s main role has been as a provider of climate finance through the Climate Investment Funds (CIFs) and its main lending activities – of which climate related lending is greater than the CIFs (Reference Dejgaard and HattleDejgaard and Hattle, 2020), but it has also sought to influence the wider governance of climate finance. The latter role has involved hosting and participating in climate finance relevant forums such as the Climate Action Peer Exchange for finance ministry representatives as well as knowledge production, including climate data on climate finance recipients (Climate Action Peer Exchange, 2020; World Bank, 2020a). The Bank has also been instrumental in promoting the CDM and developing CDM projects (Reference LazarowiczLazarowicz, 2009; Reference LedererLederer, 2012), as well as private climate finance in general. These climate efforts should be seen in the light of the Bank’s desire to be a leader on climate change (World Bank et al., 2016). Yet, there has also been criticism of the Bank’s considerable lending to fossil fuel projects (Reference Redman, Durand, Bustos, Baum and RobertsRedman et al., 2015; The Big Shift Global, 2019).

9.3.4 Regional Multilateral Development Banks

Similarly to the World Bank, the regional MDBs (the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the Inter-American Development Bank) have also scaled up their climate finance, while also facing criticism for their financing of fossil fuel projects (see Reference DelinaDelina, 2017 regarding the Asian Development Bank). In general, they have been less active in promoting climate finance and climate action than the World Bank, but have co-produced reports (particularly on the tracking of climate finance) together as a group also including the World Bank (World Bank Group et al., 2011).

9.3.5 Civil Society Actors

Various kinds of civil society organisations have also been active at the international level. These can roughly be divided into two groups: think tanks and NGOs. The think tanks include environment and development think tanks and research institutions such as the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), Overseas Development Institute and World Resources Institute, and have mainly focused on producing knowledge in the shape of reports on the global state of climate finance as well as how to implement climate finance projects. Notably, the CPI (2017, 2018, 2019) has produced regular reports providing an overview of global climate finance flows. The NGOs include mainly environmental NGOs, for example, Climate Action Network (an umbrella organisation of environmental NGOs), Greenpeace and the World Wildlife Fund, as well as development NGOs such as Oxfam. They have focused more on activism and influencing public agendas but have also (especially the World Wildlife Fund and Oxfam) produced reports on climate finance. In general, they have emphasised equity and often sided with developing countries.

9.3.6 Corporate Actors

Corporate actors, especially from the financial sector, have been very active in funding climate finance projects. Some of them have also been active in various networks promoting climate action from the corporate world, for example, the Global Investor Coalition on Climate Change and Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (2020). These networks seek inter alia to enhance knowledge about climate issues such as climate risk among investors and to promote policies facilitating climate-friendly investment as well as commitments to net-zero emissions in companies. In general, individual corporate actors as well as private networks and institutions focus on mitigation rather than adaptation.

9.4 Domestic Politics

The domestic level is arguably the most important for the actual flows of climate finance. The fragmented nature of the climate finance governance system leaves most of the decisions of how public climate finance should be allocated to the governments of developed countries (Reference Pickering, Betzold and SkovgaardPickering et al., 2017), which also hold considerable sway over MDBs. The decisions regarding how to allocate climate finance are mainly driven by domestic factors such as income, attention to environmental issues, responsibility and vulnerability to climate change, political orientation of government or the ministry that is responsible (Reference HalimanjayaHalimanjaya, 2015, Reference Halimanjaya2016; Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2011b; Reference Peterson and SkovgaardPeterson and Skovgaard, 2019; Reference Pickering, Skovgaard, Kim, Roberts, Rossati, Stadelmann and ReichPickering et al., 2015b). Developing countries have less influence over the allocation, but develop climate finance projects within their borders, sometimes together with international funders and sometimes on their own with the intention of applying for funding. Nevertheless, there are crucial influences from the international level regarding all kinds of domestic climate finance decisions, in the shape of norms, targets and other commitments, the monitoring of climate finance, and knowledge about how to allocate and implement climate finance.

9.5 Summary

Climate finance is a topic at the intersection of climate and economic politics, yet more anchored within the UNFCCC than fossil fuel subsidies. The issue is characterised by considerable contestation over what flows of finance can be defined as climate finance and which normative ideas (particularly equity or efficiency) should guide the allocation and generation of climate finance. Furthermore, the climate finance system is also characterised by institutional fragmentation. Much, but not all, of this contestation and fragmentation reflects a dividing line between, on the one hand, developed countries promoting broad definitions of climate finance, efficiency and maintaining control over climate finance and, on the other, developing countries promoting narrow definitions of climate finance, equity and influence over climate finance. How economisation has worked in the case of the institutions addressing climate finance, including the definitional issues and normative issues outlined above, within the climate finance system, is the topic I turn to next.

The November 2009 St Andrews meeting of G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors was supposed to provide key input on climate finance. At this time, climate finance was a hot topic in the climate talks going into the Fifteenth Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP15), and observers expected it be an issue where the G20 could provide crucial input (author’s observation as a government official working in the COP15 team of the Danish Ministry of Finance). Yet, the attempts to agree on a set of far-reaching conclusions at St Andrews largely failed, and since then this issue has mainly been addressed at the expert level. Thus, climate finance is similar to fossil fuel subsidies as a topic that G20 started addressing in 2009 at the ministerial level, followed by expert discussion. Yet, G20 output on climate finance in general has not had the same catalytic effect as the Pittsburgh commitment on fossil fuel subsidy reform. Nonetheless, it has had repercussions beyond the G20, especially among international institutions. How economisation played out in the case of the G20 addressing climate finance is the topic of this chapter. The chapter starts with an overview of G20 output, from the attempt to reach an agreement in 2009 to the more technical working groups that have addressed climate change from an economic perspective, followed by an analysis of the causes (entrepreneurship from Presidencies, membership circles, interaction with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCCC]) that shaped the output. Finally, the chapter discusses the consequences of this output at the international level (salient mainly regarding the UNFCCC and institutions tasked with providing analysis to the G20) and the domestic level (less discernible).

10.1 Output: Failure to Commit, Followed by Knowledge Production

In the spring of 2009, the UK Presidency played an active role in establishing an expert group on climate finance, with the purpose of delivering a report and the basis for a G20 finance ministers’ and central bank governors’Footnote 1 statement outlining their position before COP15. This statement was intended as a formal output of the November 2009 G20 meeting of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors in St Andrews (the United Kingdom). Thus, an important objective of the expert group was to influence the UNFCCC output. In the UNFCCC negotiations leading to COP15, it had become evident that climate finance commitments would be an important part of an agreement, but also that the negotiators from Annex II countries could not make credible commitments before they had been given the green light from their finance ministries. Several actors thought that the best way to avoid finance ministries vetoing or weakening climate finance commitments was to involve them in the negotiations and thus ensure that they felt a sense of ownership for the agreement and that the agreement reflected their views (Interview with senior European Commission official, 28 June 2011). Interestingly, climate change was outsourced from the UNFCCC negotiations not because it was uncontroversial (as Reference ZelliZelli, 2011 argues has been the case with the topic of reducing emissions from deforestation), but precisely because it was controversial.

In terms of informal output, the expert group sought to establish common ground through writing papers on topics such as public finance, private finance and how the different kinds of finance should be accounted for (interview with senior European Commission official, 7 September 2011). The process pressured the finance ministries in question to define their position on climate finance through analysis, that is, a process that influenced their cognitive and normative ideas regarding climate finance. The different elements of those papers were brought together in early drafts of the St Andrews Communiqué. The process also established a common ground on several issues before going into the St Andrews meeting in early November 2009 although this did not translate into an actual agreement on climate finance including commitments (interview with senior European Commission official, 7 September 2011).

The first draft from St Andrews contained several provisions that were quite far-reaching at the time given that climate finance negotiations had come to a halt in the UNFCCC negotiations, and would have constituted important regulatory output if adopted. Firstly, regarding the generation of finance, it contained the first mention of the commitment of developed countries to the USD 100 billion target – part of the Copenhagen Accord agreed a few weeks later at COP15 (interview with senior European Commission official, 7 September 2011) as well as the recognition of the different sources (including private and carbon market sources), which remained in the final St Andrews Communiqué (G20, 2009; G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, 2009). These provisions can be compared to the UNFCCC negotiation text that was discussed at that time, which contained numbers in sharp brackets ranging from the unspecified to 5.5 per cent of developed countries’ GDPFootnote 2, and sources ranging from purely public to a combination of public, private and carbon market resources (UNFCCC, 2009b). Thus, the 100 billion target was a rejection of the demand of most UNFCCC negotiators from developing countries that only public financing should count against the target, but it also meant that finance ministries in developed countries accepted the climate finance target (an idea which many of them initially opposed).

Second, the Communiqué emphasised efficiency, an approach that was more widespread among developed than developing countries but resonated better among finance ministers from developing countries than UNFCCC negotiators from the same countries. In this way, the first aspect of economisation (placing climate finance on the agenda of an economic institution) led to the second aspect of economisation (an economic framing of climate finance).

Yet, at the St Andrews meeting, the ministers were unable to agree on the draft joint statement on the table because of the United States insisting that the World Bank should be the trustee of the Green Climate Fund, and China and India opposing this (interview with senior UK Treasury official, 30 June 2011). China also insisted on references to Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR) which made a compromise more difficult to achieve (interview with senior UK Treasury official, 30 June 2011). Thus, CBDR was much more controversial than efficiency. As a consequence of these disagreements, the climate finance provisions of the official Communiqué of the meeting did not contain any significant commitments or agreements on disputed issues (Reference Vorobyova and WillardVorobyova and Willard, 2009).

Following 2009, climate finance continued to be addressed by experts under the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors, and these meetings became institutionalised with the establishment of the G20 Climate Finance Study Group (until 2013 named the Study Group on Climate Finance) during the 2012 Mexican Presidency (G20 Heads of State and Government, 2012). The Climate Finance Study Group reported to G20 Leaders on how to mobilise climate finance to meet the USD 100 billion target for climate finance agreed at COP15. The Study Group was discontinued after 2016, with the Green Finance Study Group (in 2018 renamed the Sustainable Finance Study Group) continuing some of its efforts and addressing environmental and sustainable finance from a perspective mainly focusing on private finance (Reference Hansen, Eckstein, Weischer and BalsHansen et al., 2017). These discussions were rather technical, and although the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors discussed climate finance provisions in a Paris Agreement in the run-up to the Twenty-first Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP21), the level of ambition for G20 involvement was much lower than at St Andrews (IISD, 2015a, 2015b).Footnote 3 The G20 expert groups stand out from other climate finance expert groups in terms of mainly reporting to finance ministers and because their members come predominantly from finance ministries (in the case of the Green/Sustainable Finance Study Group also central banks). While finance ministries had discussed climate change in several forums, the G20 was the forum in which this involvement was most institutionalised.

G20 study groups are seldom permanent fixtures and can be discontinued after a period of time, depending on the priorities and preferences of each new incoming Presidency (interview with former chair of G20 Study Group, 30 April 2020) or if the work set out in the Terms of Reference have been completed. The purpose of both post-2009 working groups was to provide knowledge aimed at forming the basis for discussions, rather than significant commitments similar to those the G20 aimed to provide at St Andrews. The Climate Finance Study Group was tasked with considering ‘ways to effectively mobilize resources taking into account the objectives, provisions and principles of the UNFCCC’ (G20 Heads of State and Government, 2012, para. 71).

More specifically, in 2011, the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors had requested a report on the mobilisation of climate finance from a group of International Organisations (IOs) led by the World Bank and including the IMF and the OECD (discussed in detail in Chapters 11 and 12). This report provided a basis for subsequent discussions in the Climate Finance Study Group. In 2012 and 2013, the Climate Finance Study Group delivered reports on focusing on the mobilisation of climate finance, and defining the issue in terms of meeting the USD 100 billion target without specifying any kind of burden-sharing, except that the funds should be mobilised by developed countries (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2012, 2013). In this way, it was up to the individual countries to decide how much public climate finance they wanted to provide, reflecting an approach to climate finance that was very much driven by individual national decisions. In terms of the question of what kind of finance counts as climate finance, private climate funding was framed as constituting an important source of climate finance, and carbon pricing policies were highlighted as a potential source of climate finance but also one which it was up to the individual state to decide whether it wanted to adopt. Carbon pricing was recommended with reference to its efficiency (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2012, 2013). Linking climate finance to carbon pricing is an ideal-typical case of economisation, since it links climate finance with the instrument for addressing climate change favoured by most mainstream economists (see also discussion of carbon pricing in Chapter 1 and 7).

After 2013, other issues than mobilising climate finance were included on the agenda, such as improving adaptation finance and collaboration between climate funds as well as leveraging private finance (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2014, 2015, 2016a). These issues were treated as being as important as the mobilisation of climate finance and reflected an emphasis on the efficiency of the climate finance mobilised. The approach to these issues was rather technical and avoided references to equity-oriented norms such as CBDR except for generic references to respecting the ‘principles, provisions and objectives’ of the UNFCCC (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2015). The stated objectives of the Study Groups’ reports were to share experiences and best practices, reflecting a country-driven approach in which it was up to the individual state to choose the approach that best suited its national circumstances and preferences.

Adaptation finance was addressed in the 2014 and 2015 reports with an emphasis on removing barriers to effective adaptation finance (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2014, 2015, 2016a). In general, the importance of private finance and development aid to climate finance was emphasised, as was the use of financial instruments to mobilise climate finance, leverage private finance and reduce investment and climate risks. This emphasis reflects the G20’s character as a forum for economic policy. The G20 experts did not (either before or after 2013) provide output explicitly addressing the issue of what constitutes climate finance, but only underscored the importance of tracking climate finance. The 2012 and 2014 reports underscored the divergence of opinions among the member states, particularly regarding the role of public finance vis-à-vis private finance and development aid, including whether public finance should be new and additional to Official Development Assistance (ODA; G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2012, 2014). Particularly China and India stressed the importance of public finance and additionality as well as of private finance not undermining Annex II countries’ obligation to provide public climate finance (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2012, 2014). On the other hand, developed countries focused more on leveraging private finance and improving efficiency.

The Green/Sustainable Finance Study Group had the broader purpose of exploring how to scale up green financing, understood as the ‘financing of investments that provide environmental benefits in the broader context of environmentally sustainable development’ (G20 Green Finance Study Group, 2016), p. 5) Consequently, it did not focus on the USD 100 billion target or other contested issues during the UNFCCC negotiations, but rather on private finance and issues such as greening the banking system, the bond market and institutional investors, as well as the role of risk and sustainable private equity and venture capital (G20 Green Finance Study Group, 2016, 2017; G20 Sustainable Finance Study Group, 2018). As such, it adopted an economic framing of sustainability, but one which was less focused on externalities and more on overcoming barriers to green investment such as risks. Arguably, this approach was less about textbook environmental economics targeting the nature of the problem (an externality), and more about providing economic, financial solutions to the problem. Furthermore, the focus on sustainability meant that climate change was no longer the only environmental issue addressed, although it still took up considerable space.

10.2 Causes

Regarding the first aspect of economisation, in 2009, the member states and especially the UK Presidency played an important role in ensuring that climate finance was included on the agenda, thus intentionally economising the issue. The entrepreneurship of the UK Presidency was important in shaping the level of G20 efforts regarding climate finance (interview with former senior UK Treasury official, 30 June 2011), and subsequent Presidencies were also influential in shaping the activities of the study groups, for example, the 2012 Mexican Presidency establishing the Climate Finance Study Group and the 2016 Chinese Presidency establishing the Green Finance Study Group. Later Presidencies have been less ambitious in their entrepreneurial roles than the UK, as the deadlock in St Andrews killed off the idea that the G20 could be a major game changer as regards climate finance.

In 2009, there was a general agreement among the finance ministers that the G20 could influence the UNFCCC climate finance negotiations by establishing a common understanding and agreement among the G20 members, who represent the majority of the most important states in the UNFCCC process. The membership circle was also important when the G20 was not able to reach an agreement on the more far-reaching provisions of the draft of the St Andrews Communiqué due to differences between the United States and China (and to a large degree India) regarding World Bank trusteeship of the Green Climate Fund and CBDR. Similar divisions between, on the one hand, China and India and, on the other, developed countries also characterised early discussions of tracking climate finance in the Climate Finance Study Group. These disagreements demonstrate the limits of the influence of economisation: it was impossible to overcome the deep-rooted differences between, on the one hand, China and India and, on the other, developed countries, the United States in particular. In the Green/Sustainable Finance Study Group these divisions were less pronounced as the Study Group was asked to look at mobilising private capital unlike in the climate finance groups that were focused on public sector transfers related to the UNFCCC negotiations (interview with former chair of G20 Study Group, 30 April 2020).

Furthermore, regarding the membership circle, the G20 does not include lower-income countries. Nonetheless, the G20 have addressed the issue of adaptation finance, which is primarily a concern of lower-income countries since they are the main per capita recipients of such finance, while the emerging economies are the main recipients of mitigation finance (Reference HalimanjayaHalimanjaya, 2015; Reference Weiler, Kloeck and DornanWeiler et al., 2018). In conclusion, while the membership circle mattered especially in terms of limiting how far the G20 was able to go, it cannot explain neither the emphasis on adaptation finance nor on efficiency and economic framings in G20 output compared to the positions of the G20 members in the UNFCCC.

A major factor in the way in which the G20 has addressed climate finance (the second aspect of economisation) has been its economic worldview. This worldview is evident in the general emphasis on efficiency, and the specific emphasis on the importance of private finance and development aid to climate finance, and on the use of financial instruments to mobilise climate finance, leverage private finance and reduce investment and climate risks. Climate finance is economised by treating it as an economic issue to be addressed with financial instruments (leverage, de-risking). While these trends are also evident in the climate finance output from other institutions, e.g. the UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance (2016, 2018), the G20 has to a larger degree singled them out as key issues. In this respect, the fact that most representatives of member states come from finance ministries or central banks has been an important aspect of this worldview.

Regarding the interaction with other institutions, the UNFCCC in particular played an important role. Not only was the G20 involvement in climate finance driven by the desire to influence the UNFCCC negotiations, but norms from the UNFCCC also shaped the discussions within the G20, most notably the controversy over references to CBDR. The relationship between the G20 and the UNFCCC gradually became more synergistic, going from the G20 being seen as an alternative forum to the UNFCCC for key climate finance discussions to the G20 study groups providing knowledge about how to meet UNFCCC obligations, although with a clear economic framing. The more synergistic relationship between the two institutions should also be seen in the light of the UNFCCC, especially the Standing Committee on Finance (SCF), moving in a more technical direction and leaving more discretion to the states. The move to more technical discussions in both institutions also reflects that with the adoption of the USD 100 billion target, the most important political decision had been reached, and the remaining topics were more technical. As mentioned earlier, as the G20 output became less focused on the UNFCCC’s USD 100 billion target with the Green/Sustainable Finance Group taking over, divisions among member states became less salient. This shows that (cognitive and normative) interaction with the UNFCCC regarding what counts towards the USD 100 billion target meant that divisions over this issue spilled over from the UNFCCC to the G20, although it was ameliorated by the economic worldview of the institution.

Besides the UNFCCC, the Climate Finance Study Group interacted continuously with other institutions, particularly development banks, the OECD and the Global Environment Facility and the think tank the Climate Policy Initiative, which were tasked with providing reports and other input to the Study Group (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2015, 2016b). This technical and cognitive input provided the basis for parts of the Study Group’s report.

10.3 Consequences

10.3.1 International Consequences

The UNFCCC

The international institution most influenced by the G20’s climate finance output is arguably the UNFCCC, at least as regards the Copenhagen Accord negotiations. Although the finance ministers were not able to reach a final agreement on climate finance in St Andrews, they were ready to agree on several issues which would later be found in the Accord (interview with senior European Commission official, 7 September 2011). When comparing the climate finance provisions of the St Andrews Communiqué (and particularly earlier drafts of this Communiqué) and the Copenhagen Accord, crucial similarities between the St Andrews Communiqué and the Accord stand out, as discussed in Section 10.1. Agreements (or in this case, a nearly completed agreement) in one institution affecting the possibilities for agreement in another constitute an incentive-based and cognitive influence (see also Chapter 2). Incentive-based because states would be more inclined to offer to change their negotiation positions within the UNFCCC if they knew – on the basis of the G20 negotiations – that the other states were likely to respond to such offers with similar offers. Cognitive because the G20 process established an understanding among the finance ministers of both developing and developed countries, which influenced how climate finance was addressed in the UNFCCC (interview with senior Indian Finance Ministry official, 3 November 2014). This understanding was developed in the meetings of experts and is visible in the way in which the provisions on the governance of climate finance reflect finance ministerial thinking. The G20 process meant that the finance ministries of the G20 developed countries accepted this obligation, including the obligation to fund adaptation, which runs counter to traditional finance ministerial preferences for mitigation finance, which provides a global public good (Reference Pickering, Skovgaard, Kim, Roberts, Rossati, Stadelmann and ReichPickering et al., 2015b). In this respect, it is important to note that the ‘Circle of Commitment’ that negotiated the Accord essentially consisted of the G20 minus a few middle-income countries such as Turkey and Argentina but plus representatives of country groups such as the Alliance of Small Island States and a few smaller countries. The importance of the influence of the G20 is also evident in the similarities between the Copenhagen Accord and the St Andrews text, especially when compared to how the Copenhagen Accord and the UNFCCC negotiation text differ (UNFCCC, 2009a, 2009b).

After 2009, the G20 output has not only been more modest in its ambitions, but its influence on the UNFCCC is also harder to discern. The G20 finance ministers (and central bank governors) have only had a limited involvement in the G20 discussions of climate finance, and the state leaders have been less directly involved in the UNFCCC negotiations compared to in 2009. Thus, the direct link between the two institutions at the level of highly powerful government officials has ceased to exist, and while the technical experts participating in the Climate Finance Study Group may influence their country’s position during the UNFCCC negotiations, this influence is much more indirect. Another factor is that the USD 100 billion target – despite the uncertainty regarding how it can be met – has been the most important climate finance commitment in the past twenty years. Once it was decided, there was less scope for the involvement of the political level. That meant that a key strength of the G20, its ability to agree on disputed but common political issues among twenty of the most powerful states, was less salient. The experts in the G20 Climate Finance Study Group with their economic approach differed less than the experts in the UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance. They were influenced by and part of the same trend of framing climate finance in economic terms of leveraging private finance and mainstreaming climate concerns into development aid.

Institutions Tasked with Providing Analysis

Another set of institutions influenced by the G20 output has been the institutions tasked with providing analysis to the G20 Study Groups. Unsurprisingly, given that it often acts as an unofficial G20 Secretariat, the OECD has provided many of these reports, but nonetheless these reports constitute a relatively small proportion of the overall OECD publications on climate finance (see Chapter 11). The OECD reports provided to the G20 also stressed the same issues and adopted similar framings to the other OECD publications on climate finance, and did not increase in volume after the G20 requests (see Chapter 11). Thus, the G20 hardly induced a fundamental change to the way in which the OECD addressed the issue or the OECD agenda. The same applies to another major provider of reports, namely the World Bank, which also provided a range of publications on climate finance beyond those delivered to the G20. Again, the non-G20 World Bank output is rather similar in approach and theme to the publications delivered to the G20 (see e.g. World Bank, 2010, 2013a, 2017, 2018, 2020c). Other multilateral development banks (MDBs), particularly the Inter-American Development Bank, have also contributed to the reports to the G20, although to a much lesser degree than the World Bank (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2015). UN institutions, particularly the Secretariats of both the Green Climate Fund and the Global Environment Facility, and the UNEP and UNDP, also contributed to reports to the G20, again without these reports being radically different to other publications on climate finance published by these institutions (Reference RobbinsRobbins, 2017; UNDP, 2012). Largely, the reports published by these UN institutions (both those provided to the G20 and the rest) are part of the wider trend of focusing on greening finance and investment rather than the provision of public climate finance.

All of these institutions were used to addressing climate finance, in a knowledge-producing role and/or as providers or implementers of climate finance. Arguably, the G20 commitment exerted its greatest influence over the IMF, the Bank of International Settlements and the Financial Stability Board, which were less used to addressing climate finance, and which provided reports and other input on green and sustainable financial issues such as carbon pricing and green bonds (G20 Green Finance Study Group, 2016, G20 Sustainable Finance Study Group, 2018, IMF, 2011a, 2011b). In the case of the IMF, the output addressing climate finance even decreased significantly when it no longer reported to the G20, demonstrating the G20’s influence on the IMF agenda (see Chapter 12).

10.3.2 Domestic Consequences

The arguably most important influence of the G20 on climate finance at the domestic level has been its contribution to a climate finance system in which the most important decisions are left to the developed countries providing climate finance (Reference Pickering, Betzold and SkovgaardPickering et al., 2017). As I have argued earlier, the G20 has contributed to this system via its influence over the Copenhagen Accord provisions on climate finance, a cornerstone of this system. The G20 Climate Finance Study Group also became a part of this system. The factors shaping the domestic decisions regarding the allocation of climate finance mainly consist of domestic factors (Reference HalimanjayaHalimanjaya, 2015, Reference Halimanjaya2016; Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2011b; Reference Peterson and SkovgaardPeterson and Skovgaard, 2019; Reference Pickering, Skovgaard, Kim, Roberts, Rossati, Stadelmann and ReichPickering et al., 2015b). International influences, including from the G20 (or even from the UNFCCC), have had limited direct impact. The G20 Climate Finance Study Group has worked as an important forum for learning about and developing cognitive ideas about climate finance, especially in the early years, when it was a topic that was new to experts in the Study Group (interview with senior European Commission official, 7 September 2011). In this respect, it is important to note that the G20 Climate Finance Study Group was the main institutionalised forum for finance ministry officials discussing climate finance. The EU had a similar working group also oriented towards developing the EU position in the negotiations, but which covered a much smaller share of the global population and climate finance.

In the case of climate finance, international institutions can shape two aspects of a country’s climate finance policy, namely its position in the climate finance negotiations and its provision of climate finance (in the case of developed countries) and the implementation of climate finance (in the case of developing countries) respectively. The involvement of finance ministries is generally lower than the involvement of environment and development ministries both as regards developing a country’s position in the UNFCCC negotiations (Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b; Reference Skovgaard and GallantSkovgaard and Gallant, 2015) and the provision of climate finance (Reference Peterson and SkovgaardPeterson and Skovgaard, 2019; Pickering et al., 2015), although in both cases it varies considerably from country to country. Yet, while they are less directly involved, finance ministries still hold considerable power over climate finance in all countries, particularly as regards their ability to cut funds for climate finance if it is not spent in a way that they approve of. Thus, involving finance ministry officials in G20 discussions may change the officials’ understanding of climate finance, and potentially lead them to accepting climate finance in a way they otherwise would not have done, but also to encouraging their direct involvement in climate finance to shape it to ensure that it matches their worldview.

Yet, existing research does not suggest that G20 member states are more likely to involve finance ministries in either the UNFCCC negotiations or the policy processes determining the allocation of climate finance (Reference Peterson and SkovgaardPeterson and Skovgaard, 2019; Reference Skovgaard and GallantSkovgaard and Gallant, 2015). Thus, there is no overall indication that there is a spill-over from the involvement of G20 finance ministries in G20 climate finance discussions to them becoming more involved in other climate finance policy processes.

It is possible to identify influences from the G20 through the pathways of cognitive and normative change and changes to incentive-based and public and policymaking agendas by examining the five countries studied here in greater detail (see also Chapter 2).

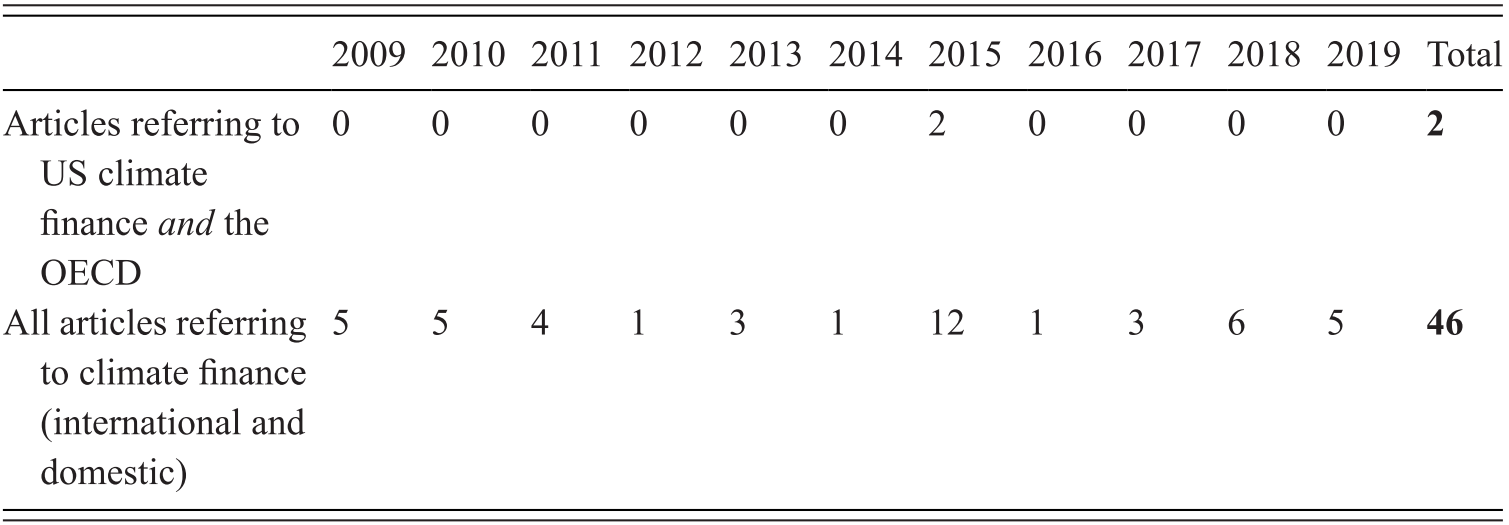

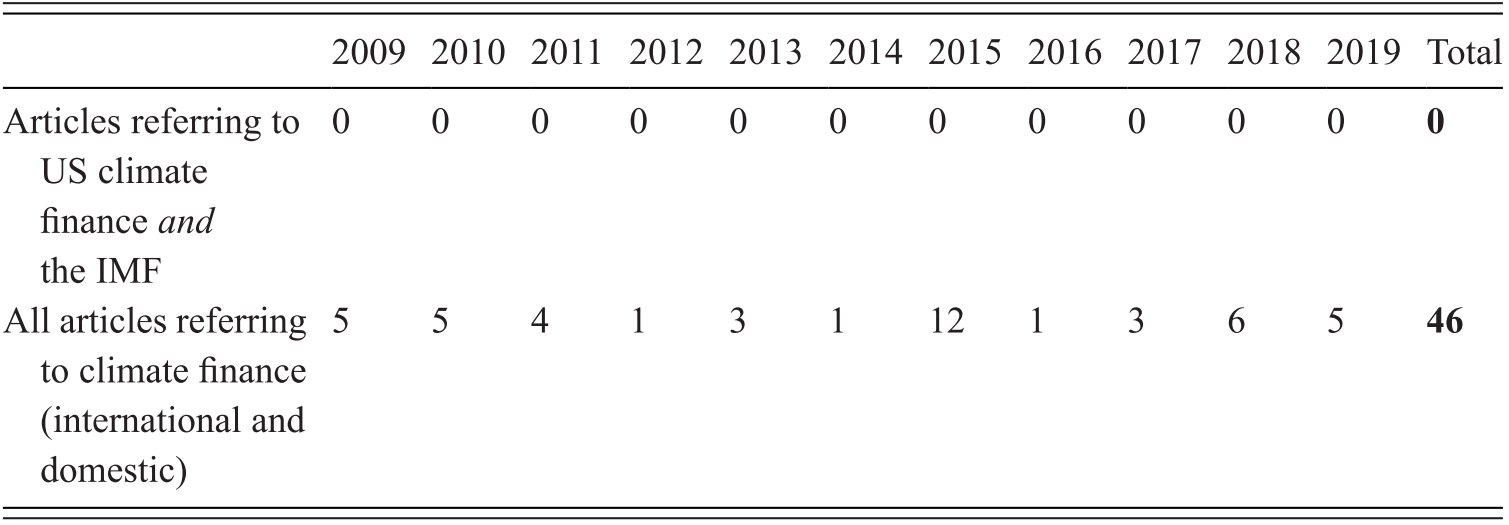

In the case of the United States, the different aspects of climate finance have predominantly been shaped by party politics. The US position in all climate negotiations including those concerning climate finance changed radically with the change of Presidents. While the Obama administration was a hardliner in the climate finance negotiations in terms of opposition to finance targets and relinquishing control over allocation, the Trump administration’s decision to leave the Paris Agreement and opposition to the GCF means it plays no role in climate finance negotiations (Reference Bowman and MinasBowman and Minas, 2019; Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b). Perhaps surprisingly, the provision of climate finance has been less affected, with levels under Trump about a quarter below 2016 levels, although the lack of transparency makes it difficult to determine the exact amounts and their allocation (Reference ThwaitesThwaites, 2019). Importantly, the United States constitutes an example of a country with a high degree of involvement of the Treasury, inter alia because it has the responsibility of financing flows to multilateral funds, including the GCF and the Climate Investment Funds (Reference Pickering, Skovgaard, Kim, Roberts, Rossati, Stadelmann and ReichPickering et al., 2015b). The US Treasury under Obama saw the G20 as a forum for climate discussions that was important in its own right and significant for addressing climate change in economic terms (Reference LewLew, 2014). Later, the Trump administration has been more sceptical of any kinds of climate discussions in the G20. Yet, even to US Treasury officials during the Obama administration it was not the only relevant forum for discussions with other finance ministry officials, as forums such as the Major Economies Forum and World Bank meetings as well as informal discussions were also important (interview with former US Treasury official, 8 April 2014). Thus, while participation in such meetings were important for cognitive influences in the shape of US officials gradually developing their understanding of climate finance issues, it is difficult to disentangle the influence from the G20 from that of other forums (interview with former US Treasury official, 8 April 2014). In terms of the US public agenda (see Table 10.1), the G20 influence was limited and the institution’s output on climate finance was only addressed in articles in the New York Times and Washington Post in 2009, in both cases focusing on how climate finance was not a major issue at the Pittsburgh Summit (Reference EilperinEilperin, 2009a; Reference GalbraithGalbraith, 2009).

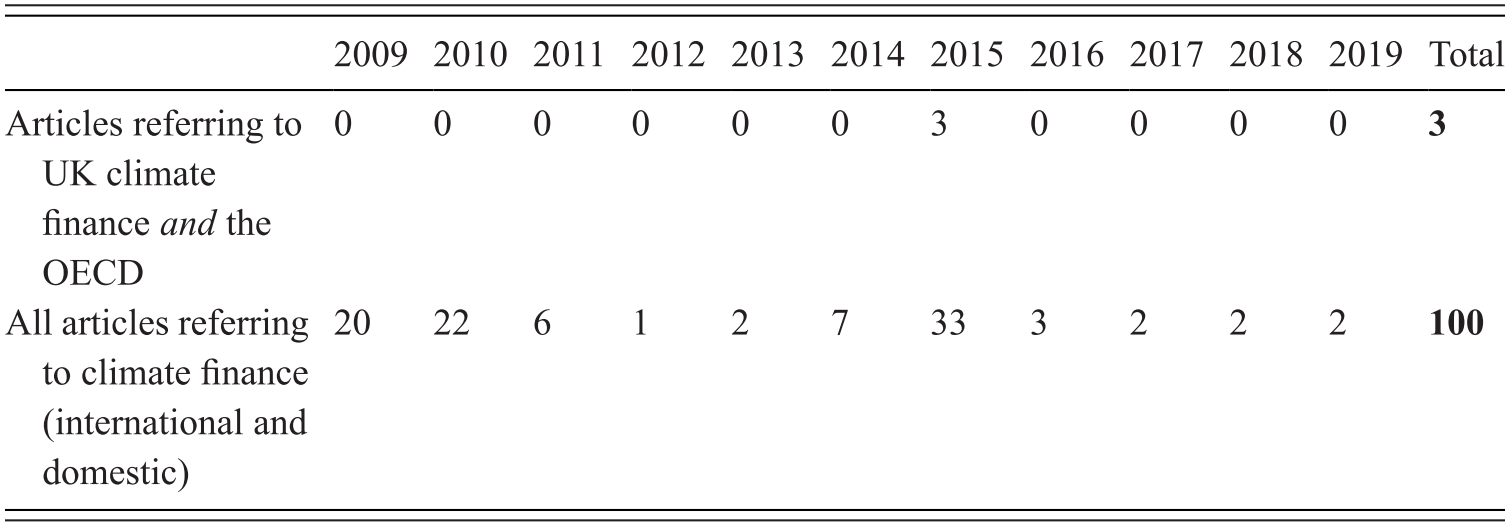

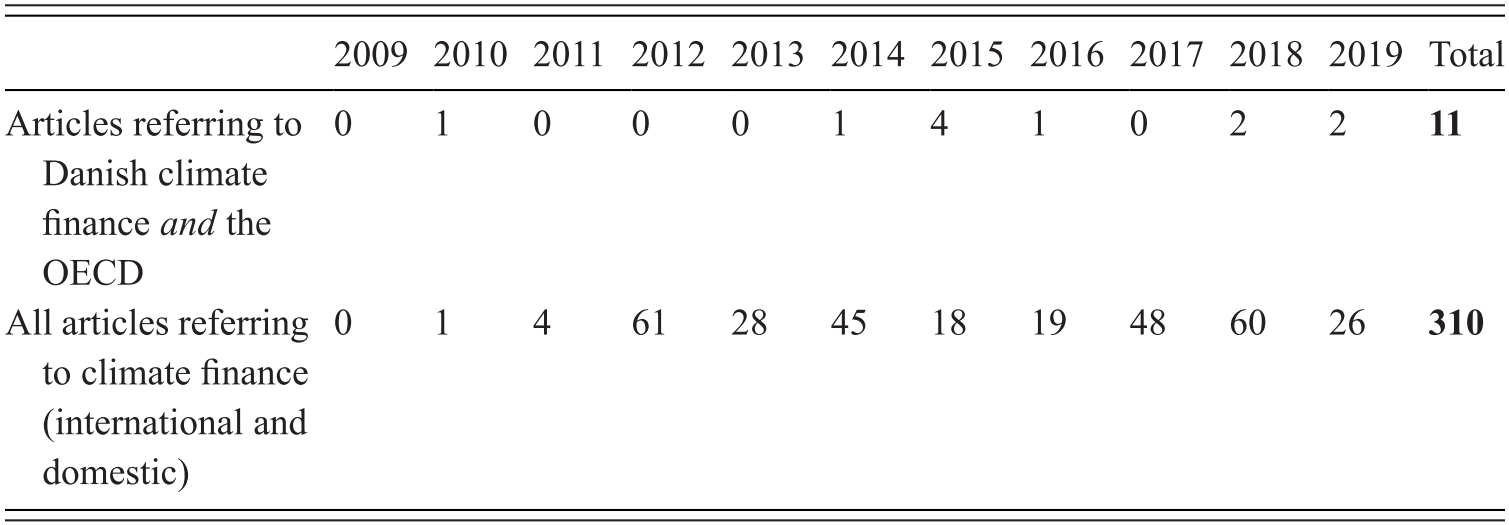

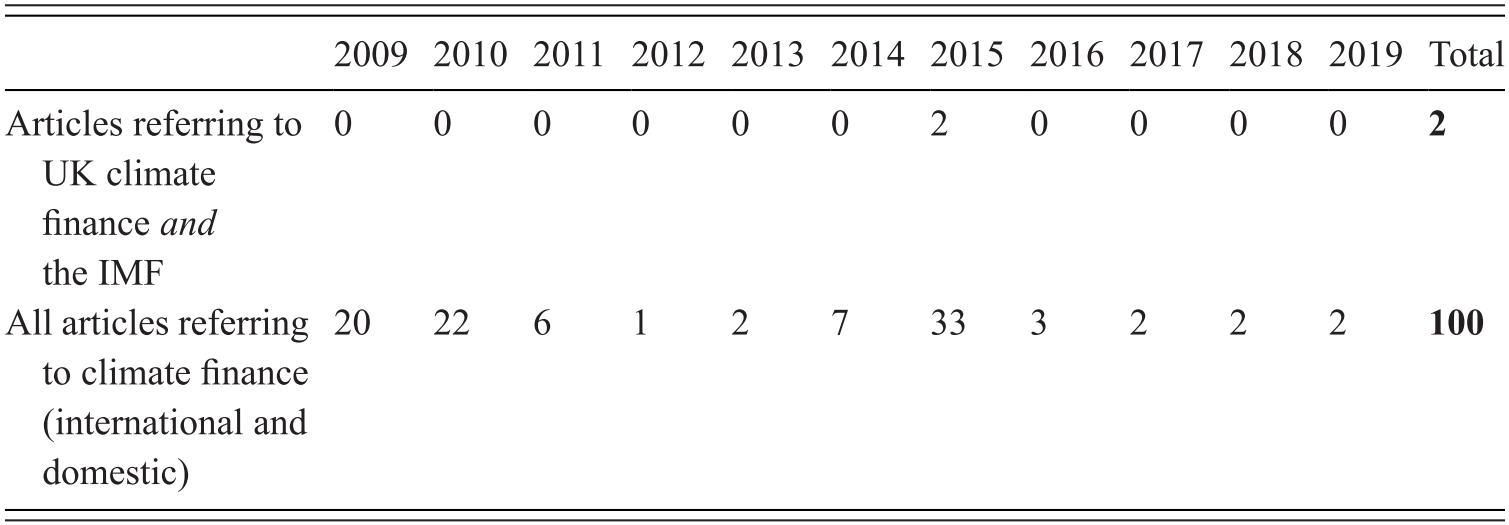

The United Kingdom has consistently had a high profile both regarding the climate finance negotiations and the delivery of climate finance (Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2015). The UK is one of the few countries that meets the 0.7 per cent Gross National Income (GNI) target for ODA, and is among the top five global contributors (Reference Atteridge, Savvidou, Meintrup, Dzebo, Sadowski and GortanaAtteridge et al., 2019). The United Kingdom has also sought to establish a common ground and promote action on climate finance in various UN and non-UN institutions, including the G20. Most notably, the UK government took on an important entrepreneurial role in establishing the 2009 climate finance expert group and as the host of the St Andrews meeting. At a later stage, the Bank of England, representing the UK government co-chaired the Green/Sustainable Finance Study Group, reflecting Bank Governor Mark Carney’s strong interest in the relationship between climate change and risk within the global financial system (interview with former chair of G20 Study Group, 30 April 2020). Thus, both the UK Treasury and the Bank of England have interacted with the G20. Similarly to the United States, participation in the G20 study groups influenced cognitive ideas in these two domestic institutions regarding climate finance issues, but this influence was limited by the UK government (especially the Bank of England at the time of the Green/Sustainable Finance Study Group) already having established an understanding of these issues when entering the G20 discussions. Notably, in spite of the relatively prominent place that climate finance has enjoyed on the UK public agenda (see Table 10.2), only two articles have linked the UK’s status as a G20 country to climate finance, in both cases noting the UK government’s reluctance to provide (new) finance to the Green Climate Fund (Reference Carrington and WattCarrington and Watt, 2014; Reference VidalVidal, 2014a).

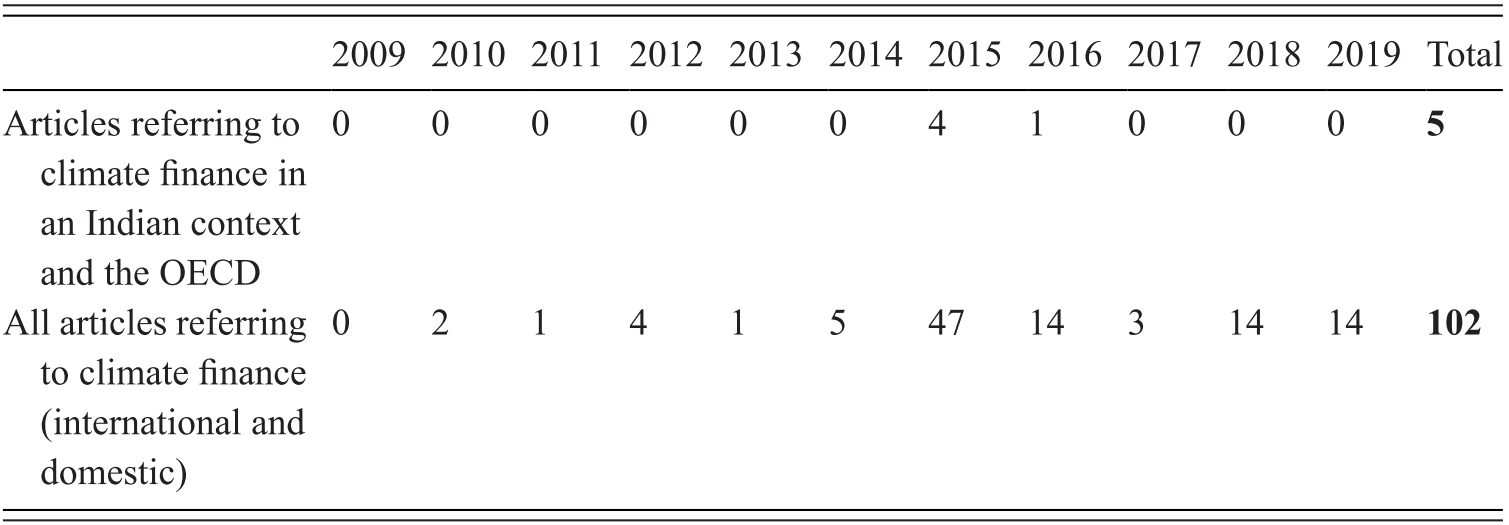

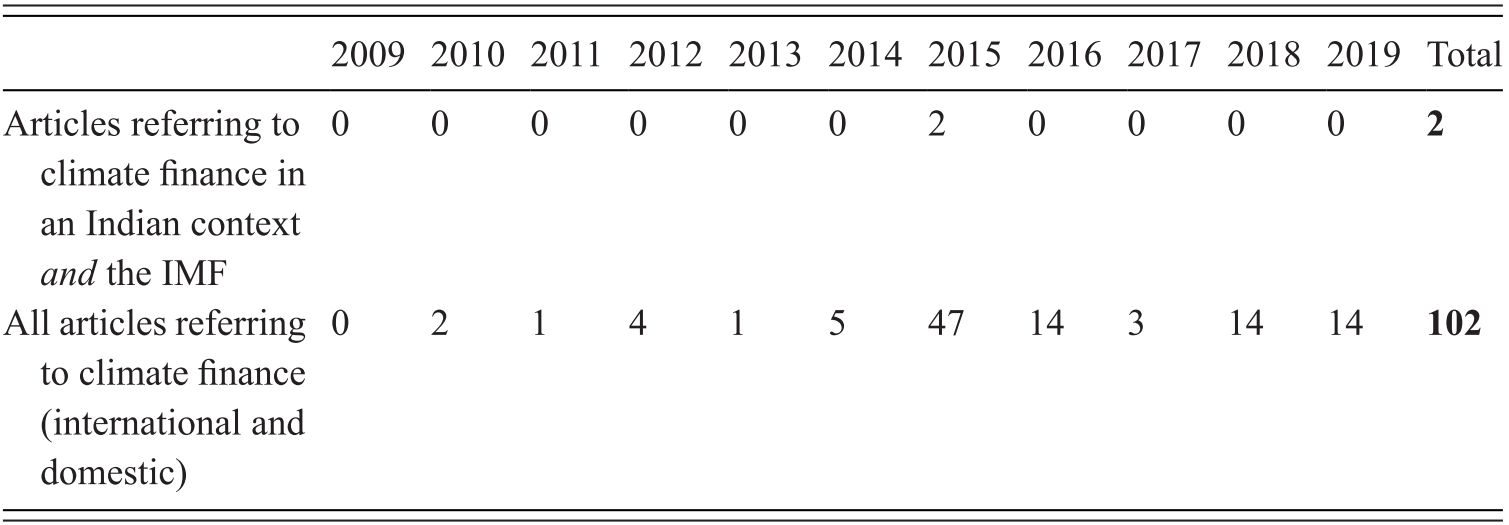

India was the largest recipient of public climate finance in the period 2002–17, having received about USD 22 billion in climate financeFootnote 4 (Reference Atteridge, Savvidou, Meintrup, Dzebo, Sadowski and GortanaAtteridge et al., 2019). In the climate finance negotiations, India has adopted a stance stressing historical responsibility, CBDR, developed country targets for public climate finance and channelling climate finance through UNFCCC institutions (Reference DasguptaDasgupta and Climate Finance Unit, 2015; Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b). The Indian Ministry of Finance has had the lead on climate finance since 2011, when a designated Climate Finance Unit was set up within the Ministry (and also leads participation in the G20). The Ministry of Finance frames climate change as an issue of equity but also of efficiency. The former is more important, since according to the Ministry, the developed countries delivering on their (equity-based) climate finance is a precondition for allocating climate finance in an efficient manner. The emphasis on CBDR has characterised the Indian position in the climate negotiations generally speaking (Reference Sengupta and DubashSengupta, 2019; Reference Thaker and LeiserowitzThaker and Leiserowitz, 2014) and is shared with other involved ministries such as the Ministry of the Environment. Regarding the G20, the Ministry of Finance is of the opinion that any decisions on climate issues need to be adopted within the UNFCCC, and the G20 is mainly a forum for economic issues (interview with senior Indian Ministry of Finance official, 3 November 2014). Nonetheless, the Ministry of Finance sees the G20 as an important forum for discussion and sharing best practices and technical knowledge, which may help clarifying and creating a shared understanding among twenty powerful countries, an understanding that may make it easier to reach agreements in the UNFCCC (interview with senior Indian Ministry of Finance official, 3 November 2014). Thus, participation in G20 expert groups has led to cognitive changes in the Ministry, affecting the negotiation position in the UNFCCC, but also how the Ministry perceives the implementation of climate finance projects in India.

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to climate finance in an Indian context and the G20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| All articles referring to climate finance (international and domestic) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 47 | 14 | 3 | 14 | 14 | 102 |

On the public agenda, the link between the G20 and climate finance existed only in the run-up and aftermath of COP21. Perhaps surprisingly, the rather modest climate finance discussions during the 2015 Turkish Presidency received most attention (Reference MohanMohan, 2015c).

As regards IndonesiaFootnote 5, the country was the second-largest recipient of climate finance in the period 2002–17, having received USD 9.7 billion in climate finance during this period (Reference Atteridge, Savvidou, Meintrup, Dzebo, Sadowski and GortanaAtteridge et al., 2019). During the climate finance negotiations, Indonesia has generally adopted a less hardline position than India. While it has stressed CBDR, developed countries’ climate finance targets and the role of the UNFCCC, it has been more positive regarding non-UNFCCC channels for climate finance and has contributed to the GCF, thus contributing to the softening of the developed/developing country distinction (Reference SkovgaardSkovgaard, 2017b). The Indonesian Ministry of Finance has been involved in the implementation of recommendations from climate finance negotiations without taking the lead on either of these two issues. In terms of the overarching framing of climate finance, the Indonesian Ministry of Finance has emphasised efficiency, signalling Indonesian readiness for climate friendly investment to the market, carbon pricing as well as CBDR (Indonesian Ministry of Finance, 2009; interview with a senior Indonesian Finance Ministry official, 24 June 2015). The Ministry’s responsibility for G20 has – together with the 2007 COP13 in Bali – increased its attention to climate change. In the G20 expert groups, the Indonesian Ministry of Finance officials have stressed efficiency over CBDR (G20 Climate Finance Study Group, 2014).

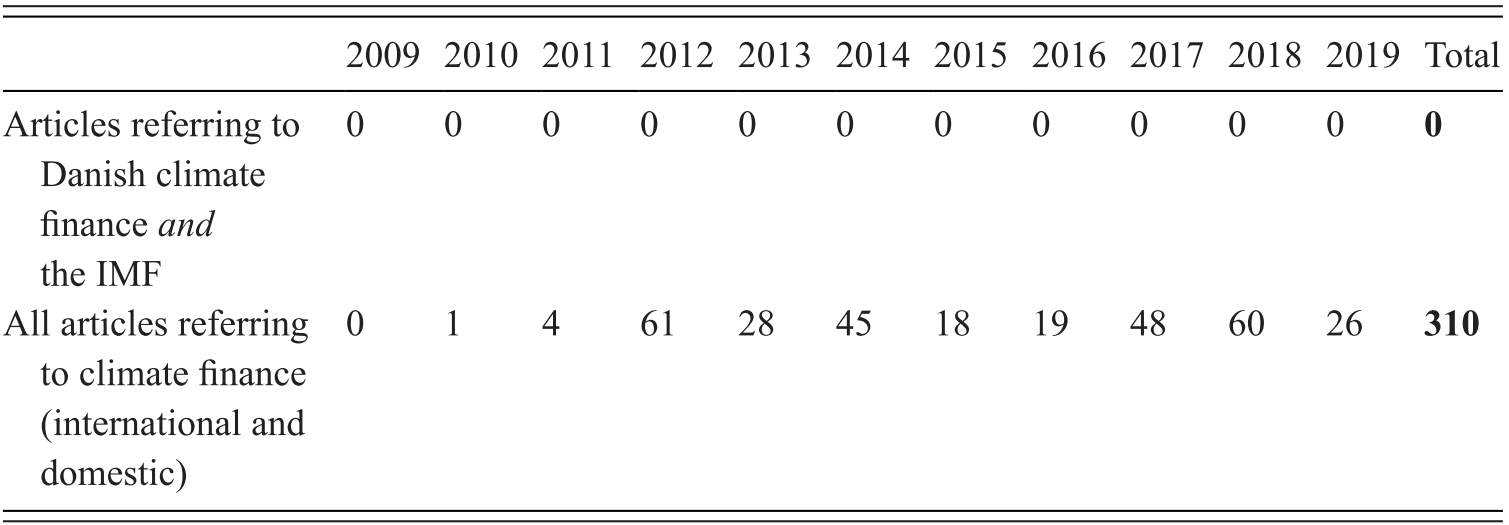

As a non-G20 country, Denmark is less relevant when studying direct influences. As regards the public agenda, a couple of articles addressed Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen giving a presentation at the St Andrews meeting, and focused inter alia on the fiscal costs of climate finance to Denmark (Reference Beder and PlougsgaardBeder and Plougsgaard, 2009; Reference Kongstad, From and BederKongstad et al., 2009).

10.4 Summary