We have one national crisis every nine days of government.Footnote 1

Introduction

Just below the surface of post-war president Hashemi Rafsanjani’s demobilisation process (1989–97), new political and social groups had made an appearance in Iranian society, bringing forth new interpretations about religion and politics, as well as up-to-date ideas about social and political reforms. They contested, constructively, the relationship between religion and state, asking for increasing political participation in the country’s domestic affairs. In other words, they demanded more representation in the institutions and the acknowledgment by the political order (nezam) of the changing nature of Iranian society. Securing the support of these new constituencies, Mohammad Khatami, the soft-spoken and intellectually sophisticated cleric, received plebiscitary support in the presidential elections of 1997, sanctioning the birth of a pluralistic and civil society-oriented political agent, the second Khordad movement (jonbesh-e dovvom-e Khordad). The birth of the reform movement left a lasting signature on the public politics of the Islamic Republic, despite its demise and cornering, up until today.

The movement, which takes its name from the victory date of Khatami’s first election, aimed to ‘normalise’ state–society relations; in the words of Ehteshami, ‘to overhaul the Islamic Republic; modernize its structures; rationalize its bureaucracy; and put in place a more accountable and responsive system of government’.Footnote 2 Normalisation, in other words, meant downplaying the revolutionary rhetoric and opening new space for the categories side-lined since the early 1980s. Making tactical use of media, in particular newspapers, the reform movement opened up new spaces of confrontation and debate, and called for wide-scale updating at a level of policy and polity. It did so not without serious backlash.Footnote 3

Younger generations constituted the backbone of the eslahat (reforms). Composed largely of the urban, educated, young spectrum of people, among whom women played an active and influential role, they called for a rejuvenation of revolutionary politics. Support came also from a multifaceted, if not very theoretical, group of post-Islamist intelligentsia, disillusioned with the static orthodoxy of state ideology and keen to foster an understanding of religion and politics which was dynamic, attuned with the post-Cold War context, ready to settle with liberal and neoliberal compromises. While intellectual circles – known as ‘new religious intellectuals’ (roshan-fekran-e dini) – espoused a theoretical, elitist and rather esoteric strategy to redesign and reform the Islamic Republic, often by appealing to the cultural and philosophical antecedents of Iran’s history, women and social activists attempted to introduce change by practice.Footnote 4 Thus occurred the curious and quantitatively important expansion of Iranian civil society, which fomented the success of, and was later fomented by, the reformist president Khatami. To use the words of political scientist Ghoncheh Tazmini, civil society needed ‘to bridge the conceptual gap that existed between society and the state – a state increasingly lacking in civic input’.Footnote 5 Hence, civil society became also a governmental instrument to circumnavigate the many hazards along the path of societal reforms. As a member of the Majles said by the end of the Khatami mandate, ‘If you interpret reform as a movement within the government, I think yes, this is the end. But if you regard it as a social phenomenon, then it is still very much alive’.Footnote 6

The change in Iran’s political atmosphere brought about by Mohammad Khatami’s election, combined with the influence of experts’ knowledge, opened up an unprecedented, and rather unrestrained, debate about how to deal with social dilemmas and, especially, with the problem of drug (ab)use. This chapter intends to discuss the changes preceding Iran’s harm reduction reform – the set of policies that enable welfare and public health interventions for drug (ab)users – through an analysis of the social and political agents that contributed to its integration in the national legislation. The period taken into consideration coincides with that of the two-term presidency of Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005), but with some flexibility. After all, the timeframe is intended to give a conceptual system in which reformism à la iranienne overlaps with a broader movement in support of harm reduction. As such, the two phenomena never coincided, but they interacted extensively.

Without dwelling on the actual narratives of the reform movement, which have been thoroughly studied elsewhere, one can infer that with the onset of the reformist era, the field of drug policy entered concomitantly with higher polity into the playground of revision and reassessment. Most of the reforms promoted by the presidency had ended in resounding failure, the most evident case being Khatami’s debacle of the ‘twin bills’ in 2003 and the limitations on freedom of expression that were powerfully in place at the end of his presidency. The first one refers to two governmental proposals that would have bolstered the executive power of the president and curbed the supervising powers of veto of the Guardian Council. The latter institution oversees eligibility criteria for the country’s elections and it has repeatedly been a cumbersome obstacle to reforms. Targeted by the judiciary throughout the early 2000s, the reformist camp had been cajoled into helplessness and disillusionment towards the perspective of institutional reforms and change within the higher echelons of the Islamic Republic.

After introducing reformism and the contextual changes taking place over this period, the chapter sheds light on the changing phenomenon of drug (ab)use and how it engendered a situation of multiple crises. It analyses the process by which the Iranian state introduced reforms within the legislation. These changes were not the result of instantaneous and abrupt political events, rather they followed a fast-paced, directional shift in attitude among expert knowledge, the policymaking community and the political leadership. Although the Chapter travels through the historical events of the reformist government, it does so only with the aim of casting analytical light on the how harm reduction became a legitimate public policy. Thus, it scrutinises the interaction between public institutions, grassroots organisations and the international community in their bid to introduce a new policy about illicit drugs. Key to the proceeding of this chapter is the conceptualisation of ‘policy’. As discussed in Chapter 1, policy identifies a set of events, in the guise of processes, relations, interventions, measures, explicit and hidden actions, declarations, discourses, laws and reforms enacted by the state, its subsidiaries or those agents acting in its stead. It also includes medical statements, webs of meaning, semantic spaces with a complex ‘social life’, agency and unclear boundaries. This holistic understanding of policy fits the definition of ‘apparatus’, a device that coalesces during times of crises and which is composed of ‘resolutely heterogeneous’ categories, as in the case of Iranian reformism.Footnote 7

Crisis as an Idiom for Reforms

Since the successful eradication of poppy cultivation during the 1980s, most of the opiates entering into Iran originated in Afghanistan. Between 1970 and 1999, Afghan opium production increased from 130 tons to 4600 tons annually. This stellar increase is justified as a counter-effect of the ban in Iran and Turkey and the spike in demand for opiates, especially heroin, in Europe and North America.Footnote 8 Opium flow had been steady over the course of the 1980s and the 1990s, but the advance of the Taliban since 1996 and the capture of Kabul by their forces in September of that same year, signalled important changes for Iran’s drug situation. In control of almost the entire opium production in Afghanistan, the regime in Kabul negotiated with the international community – in particular the antecedent to the UNODC, the UNDCP, a ban on the cultivation of poppies in all the territories it controlled – in exchange of international development aid. Scepticism being the rule vis à vis the Taliban among international donors, most of the funds for alternative farming were held back and Afghanistan produced a record of 4,600 tons in 1999.Footnote 9 Funded by Saudi and Sunni radical money, the Taliban forces put up strong anti-Iranian opposition. The drug flow meant Iranian authorities’ strategy on illicit drugs bore little results. Iran’s long-term ally in Afghanistan, the Northern Alliance, had previously agreed to a ban of the poppy in June 1999, but with no effect on the actual opium output because most flowers grew in Taliban-controlled lands. The following year, though, an order of the Mullah Omar, the Taliban’s political leader, abruptly banned poppy cultivation and 99 per cent of opium production stopped, with only 35 tons being produced.Footnote 10 The effects of this were immediate on the Iranian side: an upward spiral in the price of opium (more than 400 per cent rise)Footnote 11; and a lack of supply to Iran’s multitudinous opium users signified a shock in the drug market (Figure 4.1, Figure 4.2).

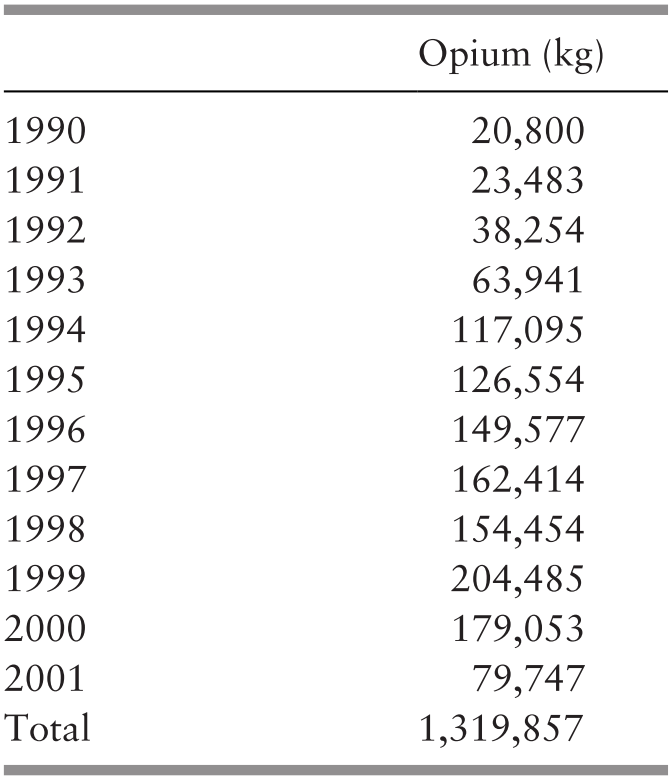

Figure 4.1 Share of Narcotics as Global Seizures (1990–2001)

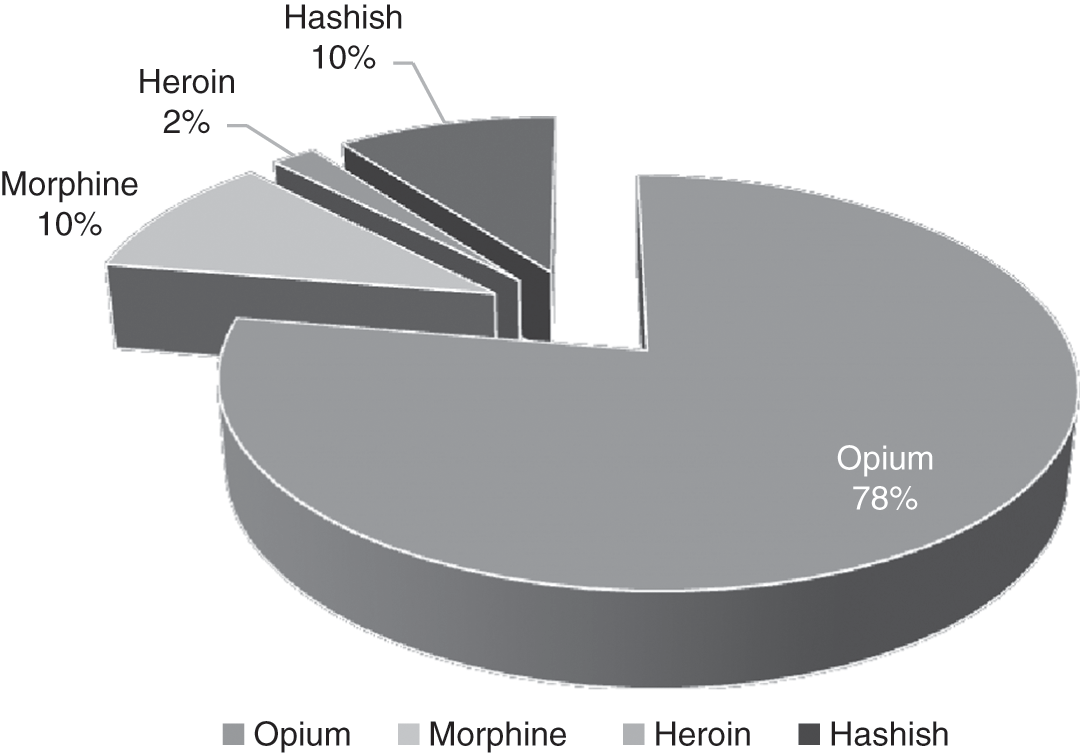

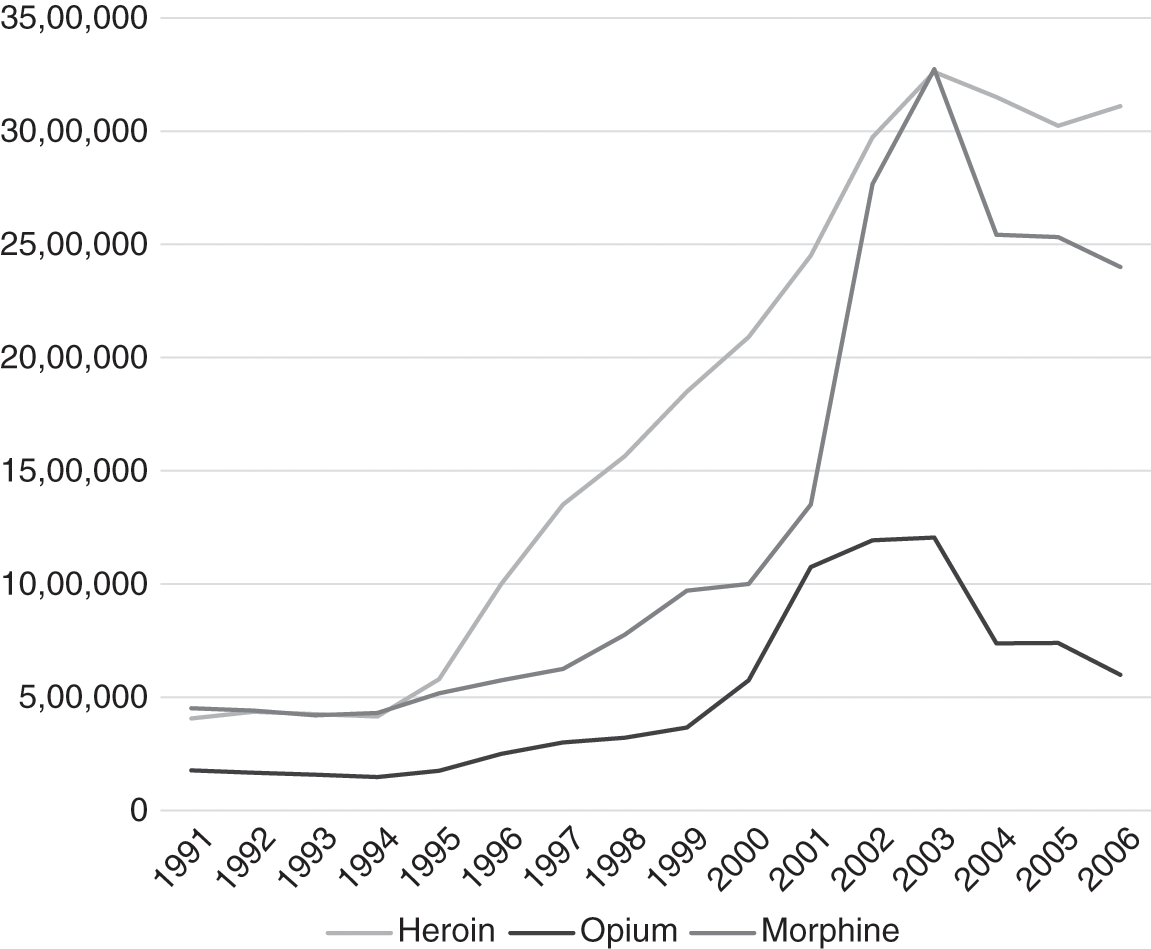

Many older drug users recall the effect of the Taliban opium ban with tragic remembrance. Many had seen their friends falling sick, or worse, dying.Footnote 12 With opium out of the market and heroin both impure and exorbitantly costly, people who had previously smoked, sniffed or eaten opium, shifted first to smoking heroin (as this had been the most common form of use in Iran, because of the high purity) and then to injecting it.Footnote 13 The death toll due to drug (ab)use reached record levels and confirmed the risk of a massive shift among drug users to heroin (Figure 4.3). It was the production of another crisis within the discursive crisis of drug phenomena (Table 4.1).

Figure 4.3 Prices of Illicit Drugs (tuman per kg)

Table 4.1 Opium Seizure, 1900–2001

| Opium (kg) | |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 20,800 |

| 1991 | 23,483 |

| 1992 | 38,254 |

| 1993 | 63,941 |

| 1994 | 117,095 |

| 1995 | 126,554 |

| 1996 | 149,577 |

| 1997 | 162,414 |

| 1998 | 154,454 |

| 1999 | 204,485 |

| 2000 | 179,053 |

| 2001 | 79,747 |

| Total | 1,319,857 |

DCHQ Officials had previously tried to compel the Taliban government to reduce opium production, but they had not envisioned the crisis that a sudden fall in opium supply could cause among Iranian drug (ab)users. With skyrocketing prices and increasing adulteration of the drug, many opium users opted to shift to heroin, which was more available and, comparatively, cheaper. Heroin, because of its smaller size and its higher potency, had been easier to smuggle in, despite the harsher penalties that this faced. Small quantities of the drug produced more potent effects on the body, reducing withdrawal symptoms (Figure 4.4).

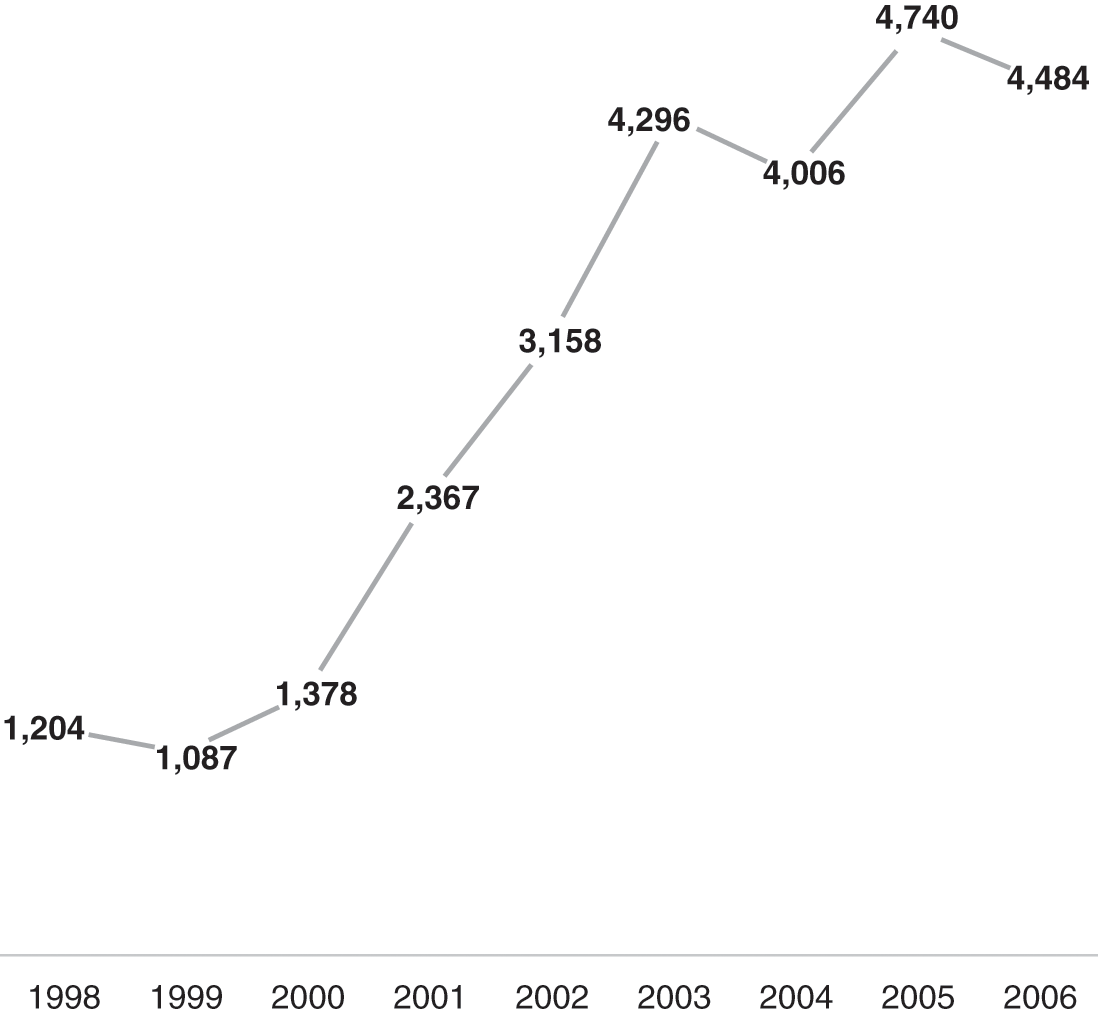

Figure 4.4 Number of Drug-Related Deaths (1998–2006)

It is unclear whether the increase is related to the increase in the numbers of drug users. It may indicate the higher impurity of opiates or a general shift towards injecting opiates which trigger a higher risk of overdose.

Heroin posed a greater threat than opium; the latter had maintained its status as a traditional substance and had further regained authority – as a miraculous painkiller – among many war veterans who suffered from chronic pain and post-traumatic effects and ‘mental distress’.Footnote 14 Heroin use among larger sections of the population signalled the shift towards more modern consumption habits, with many complexities and challenges such as the risk of HIV-AIDS, hepatitis and other infectious diseases. Injecting, hence, bears twice the negative mark of drug use. It is culturally seen as exogenous and estranged from the traditional style of use (e.g. eating, smoking), which incorporates sharing as an essential part of the drug-use culture, and can therefore be interpreted as Westernised, if not Westoxified.Footnote 15 Although within injecting-drug-user communities sharing also signifies commonality and mutuality, it is cast as dangerous and socially harmful in mainstream society, as it symbolises both destitution and HIV risks. In Iran, the stigma on injection embodied the bottom-line of drug use, the tah-e khatt (endline).

The increase in heroin use engendered a situation of perceived crisis throughout Iran’s policymaking community. State officials discussed the need to manage the Afghan opium market and to intervene directly in Afghanistan to secure the supply of opium, preventing drug users from shifting to substances that were more dangerous. Iran entered in negotiations with international partners concerning possible Iranian involvement in Afghanistan at the end of 2000, aimed at purchasing the entire Afghan opium harvest and transforming it into pharmaceutical morphine. This proposal was turned down due to international opposition, allegedly by the United States.Footnote 16 At that point, Seyyed Alizadeh Tabatabai, who acted as advisor to Khatami in the DCHQ and was a member of the Tehran City Council, put forward the bold proposal of trading Iranian wheat for Afghan opium.Footnote 17 He also suggested that for those addicts who could not be treated, the government should provide state-sponsored opium in order to ‘reduce harm’ for society, while also exporting the excess quantities in the form of morphine.Footnote 18 Despite the failures of these initiatives, the change in attitude indicated a new pragmatism towards the drug problem, one which did not concentrate exclusively on drugs per se, but attempted to read them within the broader social, political and economic context of late 1990s. The discursive shift was also a symptom of the reformist officials’ unease with the country’s stifled and uncompromising ‘War on Drugs’. The remarks of public officials implied a ‘harm reduction’ mentality broader than the field of drugs policy, permeating a new vision (and ideology) of state–society relations. It was also the litmus test about Iran’s willingness to introduce reforms in the field of drugs, as a matter of urgency. At the heart of the reformist camp infatuation with a new approach to drugs and addiction was a quest for reforming society at large; not simply agreeing to change a technical mechanism within the drug policy machinery.

There were discussions in the medical community about the immediate necessity of a substitute for opium, which was becoming costly and hardly available. Meetings took place in different settings – within the DCHQ, the Ministry of Health and in workshops organised by the UNODC.Footnote 19 Discussions started about introducing methadone into the Iranian pharmacopeia to offer it to all opium users as a legal substitute.Footnote 20 The medical community urged the government to act rapidly to prevent a massive shift towards heroin use, an event which could have had lasting consequences for the country’s health and social outlook. There were strong disagreements about the introduction of methadone,Footnote 21 but methadone was recognised as a substance embodying useful features in the management of the opiate crisis. Its pharmacological effects had the potency to perform as a synthetic substitute to opium and heroin, without compelling the government to reintroduce the cultivation of poppies (which was deemed morally problematic after the prohibition campaigns of the 1980s). Methadone created a strong dependence in the patient under treatment, at times stronger than heroin’s, but without its enduring rush of pleasure and ecstasy, which was seen as one of the deviant aspects of heroin use by the authorities. Moreover, it was relatively cheap to produce since Iran had already developed its pharmaceutical industry in this sector.

By the time the authorities discussed the introduction of methadone, in the early 2000s, there were reports about a new drug, kerak.Footnote 22 Not to be confused with the North American crack, the Iranian kerak (aka kerack) is a form of compressed heroin, with a higher potency. Kerak was cheaper, stronger and newer, appealing also to those who wanted to differentiate themselves from old-fashioned opium users and the stigmatised heroin injectors.Footnote 23 Its name reprised the North American drug scene of the late 1980s and the ‘crack epidemic’, but it had no chemical resemblance to it. Iran’s kerak had a higher purity than street heroin and was dark in colour, while US crack was cocaine-based and white. The name, in this case, operated as a fashion brand among users who regarded kerak as a more sophisticated substance, which, despite its chemical differences, connected them to American users and global consumption trends. It soon became evident that kerak consumption had similar effects to that of heroin, despite it being less adulterated during the early 2000s.Footnote 24

Meanwhile, public officials hinted at the average age of drug (ab)use falling. In a country where three quarters of the population were under thirty, it did not take long before the public – and the state – regarded the kerak surge as a crisis within the crisis, a breeding ground for a future generation of addicts. By 2005, kerak was already the new scare drug. With the rise in drug injecting and an ever-rising prison population, Iran was going downhill towards a severe HIV epidemic. In discourse, doctors, experts, and political authorities were contributing to a new framing of the crisis.Footnote 25 The medical community had tried to sensitise the government about the dangerous health consequences of injecting drug habits in prison, but prior to the reformist government, the normative reaction among decision-makers was denial. Mohammad Fellah, former head of the Prison Organisation (Sazman-e Zendan-ha-ye Keshvar) and knowledgeable about the challenge represented by incarcerating drug (ab)users, on several occasions demonstrated his opposition to the anti-narcotic model adopted over those years. Overtly, he maintained that prison for drug crimes is ineffective.

Iran’s prison population had increased consistently since the end of the war, with the number of drug offenders tripling between 1989 and 1998 (Figure 4.5). In 1998, drug-related prisoners numbered around more than 170,000. The situation became so alarming that the head of the Prison Organisation publicly asked the NAJA ‘not to refer the arrested addicts to the prisons’.Footnote 26 For a country that had declared an all-out war on narcotic drugs since 1979, and paid a heavy price in human and financial terms to stop the flow of drugs, availability of drugs in prisons – a presumably highly secure institution – meant that the securitisation approach against drugs had failed. If denial had been the usual reaction of the authorities in the 1980s and early 1990s, the HIV and hepatitis crises of late 1990s had prevented any further camouflage.

Figure 4.5 Drug-Related Crimes (1989–2005)

As Behrouzan holds, ‘understanding the role of prisons in the spread of HIV and AIDS was critical to the policy paradigm shift that occurred in the 1990s’.Footnote 27 Although there had been some attention to the issue of HIV in the early 1990s, this had never turned into an explicit and comprehensive policy with regard to HIV prevention. It was only in 1997, that the government commissioned, under pressure from the National Committee to Combat AIDS (set up in 1987), the first study of HIV prevalence in three provincial prisons: the Ab-e Hayat prison in Kerman province, the Abelabad prison in Shiraz and the Dizelabad prison in Kermanshah. The results were disturbing. Almost 100 per cent of drug-injecting prisoners were HIV-positive, many of them married.Footnote 28 Kermanshah had seen the number of HIV infected people going up from 58 cases in 1996, to 407 cases in 1997 and 1,228 cases in 2001.Footnote 29 Crisis took the form of an epidemic semantically and ideologically associated with so-called Westoxified behaviours (sexual promiscuity, homosexuality, injecting drugs). For a state governed under imperatives of ethical righteousness, moral orthodoxy and political straightness, the HIV epidemic bypassed the frontiers of public health and touched those of public ethics and politics. The reactions oscillated between silent denial among some and hectic alarmism among others. The governmental team of the reformist president tipped the balance in favour of forward-looking approaches to the HIV epidemic and allowed civil society organisations to intervene in this field. Failure meant necessity for reforms. Crisis in the moral coding of the Islamic Republic confirmed the need to update, to reform the political order in line with new challenges.

During the Twenty-sixth Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly on HIV/AIDS in 2001, the deputy Minister of Health declared to the international community,

the epidemic has been given due attention during the past years in order to stem and combat its spread … we believe that international assistance, particularly through relevant agencies, can certainly help us to pursue the next steps.Footnote 30

Iran’s HIV epidemic, generally caused by shared needles, spread rapidly in the country’s western provinces that had suffered the effects of the eight-year war with Iraq. There, the psychological and physiological traces of the war materialised in the form of massive drug (ab)use. HIV prevalence was highest (more than 5 per cent) among prisoners in Khuzestan, Hormozgan, Kermanshah and Ilam.Footnote 31

In south-western cities, large-scale displacement, destruction of dwellings and infrastructures and psychological unsettledness during the 1980s was followed by paucity of employment opportunities and lack of adequate life conditions (lack of infrastructure, air pollution) from the 1990s onwards.

The ground for reforms developed through local experimentation. Policymakers implemented these experimentations in policy on the social and spatial margins. These margins were both geographical and ethical, overlapping with the most unstable disorderly categories among Iran’s millions-strong drug-using population. The first group of people was that of the homeless, vagrant heroin and kerak users on the outskirt of the cities and in the once-known gowd of Southern Tehran.Footnote 32 Other categories included rural men who had moved into the urban centres, mostly Tehran’s peripheries, in search of occupation, which often resulted in desultory jobs, further marginalisation and the adoption of more sophisticated style of drug use (heroin, kerak use versus traditional opium smoking). The second category was that of the prisoners. The two categories had mostly overlapped in the country’s modern history, where the main target of systematic police repression has been the street drug (ab)users.

In particular, the epidemiology of HIV transmission among drug-consuming prisoners had a far-reaching influence on the policy outcomes. The journey of the virus from inside to outside the prison describes the genealogical trajectory of Iran’s harm reduction. As the crisis originated inside prisons, the policy had to be subject to experiment first in the prison context, evaluated and then propagated outside (Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6 Methadone Clinics in Prisons

The year 1381 corresponds to 2002–3 in the Gregorian calendar.

The introduction of harm reduction programmes in prisons followed a broader reform project within the Prison Organisation. In 2001, the head of the Prison Organisation submitted a letter to the Head of the Judiciary to request his opinion and support for the prison reform. This included the abolition of prison uniform which ‘humiliates the criminals, [and it] is contrary to the correctional purposes of prisons’,Footnote 33 increased training and free time for prisoners, and providing alternatives to incarceration.Footnote 34 The latter was the object of complex debate within the institutions. Although the topic did not exclusively relate to drug offenders, the issue of drug policy reform was the panacea for the prison system. In 2005, a group of seventeen MPs requested abrogation of the 1980 ‘Law for strengthening sanctions for drug crimes’ – the major pillar of post-revolutionary policy about drugs – to enable the judge to take into consideration elements such as age, gender, social and family condition, to avoid harsher sanctions and, tactically, the overcrowding of prisons. By 2005, drug offenders made up about 60 per cent of the prison population, the great majority men (90 per cent).Footnote 35 Drug users represented 50–60 per cent of prisoners, many of whom had started injecting in prison, usually with shared needles. The push towards a reform of the criminal law, with reference to alternatives to incarceration, was envisioned within the idea of state–society reforms promoted during Khatami’s presidency as much as in response to a critical stage in prison management.

A reality of crisis, both symbolic (ethical legitimacy of the Iranian state) and material (the epidemics of HIV, prison plus injecting drug use) triggered policy change and political reforming. It was the manifestation of a politics of crisis rooted in the post-revolutionary, post-war ideology of government, and governmentality. In the years after the war, social categories such as war veterans, women and young people were increasingly using drugs, with the signs of this phenomenon being more evident in public by the day. Comparisons with the pre-revolutionary period revealed a worsening of the drug phenomenon, despite the material and rhetorical efforts of the political leadership. Those who had lived during the Pahlavi regime’s years, recalled the issue of drugs as mostly a weekend vice among elderly people, while a glance at the 2000s situation showed every social strata, and all generations, affected by illicit drugs. A legitimacy crisis for the Islamic Republic was on the way, through the historicisation of political/social phenomena, by which people and politics interpreted the crisis. With two decades having passed since the Islamic Revolution, policies were being disposed within a frame that contemplated a historical chronology. The adoption of crisis as an idiom of reform became part of this historisation process.

To respond to the failures of the present, public agents from different official and civic venues initiated a reformist bid in the field of drugs policy. Their concerted tactics resulted in Iran’s harm reduction strategy.

Harm Reduction: Underground, Bottom-Up and ‘Lights Off’

Towards the end of the 1990s, public discourse hinted at the failure of Iran’s two-decade war on drugs, but statements by officials were only moderately critical, with a few exceptions.Footnote 36 The state sought the way out of the impasse through collaboration with non-state organisations, in order to intervene without directly being involved in the thorny question. Evidently, drugs and HIV had political underpinnings that could mire the reformist government. Public officials promoting reformist methods on drug (ab)use and the HIV epidemic adopted medical, pathological frames. Rooted in the way social sciences and scientists in general discuss societal and sociological matters, the social pathology inclination is deep-rooted in Iranian politics. Through this lens, unorthodox behaviour, anger, crime and other ‘deviant realities’ are read as pathologies of society, of modernity, of the city, of globalisation and so on. This historical inclination overlapped with the reintegration of the medical community in the post-war period resulting in a new place for medicine – and, hence, pathological frames – in politics.

Medicine and pathological frames had a productive effect too. Legitimated by their ‘scientific’ discourse, doctors had more leeway to intervene in the public debate. Their arguments resonated positively also with Islamic law, where the priority of individual and public health justify unorthodox interpretation of the law – and of government. Their criticisms remained within the realm of public policy, of mechanism, of management and of community welfare. It did not discuss changes in the political order, in politics at a higher level. Medicine became a malleable tool for supporters and antagonists of reforms, a venue to express resentment and critical thoughts regarding contemporary Iran, its social and political failures, without endangering the political order and its ethical primacy.

In this socio-political ecosystem, the synergies between public officials, medical professionals, civil society groups and international drug experts coalesced around the need to reform Iran’s drugs policy. Individuals in the anti-drug administration made good use of their clout ‘from below’ in the law-making machinery of the state; civil society groups intensified their grassroots operations, helped by financing and knowledge provision of international organisations inside Iran. This assemblage of forces gave birth, rather rapidly – in about four or five years – to a structured and multi-sectorial harm reduction system operating countrywide. These practical steps in the making of a legalised harm reduction field preceded the Head of the Judiciary Ayatollah Mahmud Hashemi-Shahrudi’s approval of ‘harm reduction’. In January 2005, the judicial branch issued a decree supporting needle exchange programmes and warning against interference by state organisations (e.g. police and judiciary) with these ‘needed and fruitful public health interventions’.Footnote 37 On June 8, 2005, after a process of several years, President Mohammad Khatami’s ministerial cabinet, at the suggestion of the Head of the Judiciary, approved the bill of ‘Decriminalisation of treatment of those suffering from narcotic drug abuse’. The law entrusted ‘the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Social Security with all the duties and responsibilities of prevention, treatment and harm reduction of narcotic and psychoactive drug use’.Footnote 38 Those operating in drug policy regarded the move as an effective decriminalisation of addiction’ and an Islamic juridical backing of substitution and maintenance treatment, exemplified by methadone treatment and needle exchange programmes.

For the first time, the notion of harm reduction was included in the national legislation of the Islamic Republic of Iran.Footnote 39 By providing drug (ab)users with clean and sanitised paraphernalia (needles, condoms, etc.), harm reduction support centres do not require drug users to give up drug use. From an ethical standpoint, the approval of harm reduction signified the acceptance that drug consumption is an inescapable aspect of human life, to which governments need to respond by reducing harms and not by ideological opposition. Harm reduction was a realistic response, with pragmatic underpinning. How did a conservative juridical branch turn in favour of contentious practices of needle exchange programmes and methadone substitution inside and outside prisons, when it had previously taken up a total ideological combat against drug consumers?

Civil Society as the Government by Practice

It is often argued that Bijan Nasirimanesh, a GP interested in addiction treatment, started the first harm reduction centres in Iran.Footnote 40 Nasirimanesh had started an experimental, underground needle exchange programme in the mid 1990s, in Marvdasht, located in the province of Shiraz. Later this experiment was given the name of Persepolis NGO Society for Harm Reduction and worked as a semi-legal drop-in centre (DIC). A DIC is a space where vulnerable individuals can seek low-threshold, welfare support. They often address the very basic needs of pauperised drug (ab)users, homeless and mendicant people, or sex workers.

While operating the DIC, Nasirimanesh lobbied to get his activity recognised and legalised by the authorities. ‘I was a very junior doctor but they took it seriously’ he says in an interview. ‘They didn’t want to implement these things themselves, so having a nongovernmental organization like Persepolis ready to do whatever – it was a perfect match. They didn’t say no to a single thing!’Footnote 41 Persepolis NGO obtained a license from the Ministry of Health in 2001 to operate within the legal framework. The process, once initiated, did not encounter hindrances or administrative obstacles and, according to the NGO founder, ‘was actually facilitated and encouraged by governmental institutions’.Footnote 42 Following the success of the first DIC, Nasirimanesh established another DIC in Tehran, with outreach programmes in the more destitute areas of the city, around the area of Darvaz-e Ghar, between Moulavi and Shush Squares. Participation of the local community and of the people treated was key to the philosophy of action promoted in the DICs. The outreach workers recruited from the drug using communities in the areas of interest would head off to the patoqs (drug using/dealing hotspots) once or twice a day, distributing condoms, clean syringes and giving basic medical care to largely, but not necessarily, homeless drug users. Their encounters with drug users introduced public health measures in a community previously ignored by public institutions. Outreaching drug users enriched knowledge about the drug phenomenon, reordering what the public simply cast as disorderly groups and helpless people.

By the early 2000s, the patoqs had become part of the urban landscape of Tehran and other major cities. Often also labelled ‘colonies’ (koloni) of drug users, the patoqs of the early 2000s embodied the material face of marginality in the urban landscape. Large groups of destitute, sun-burnt men and women gathered in ‘nomadic’ settlements, in parks, alleys and sidewalks, living in an economy of petty dealing, garbage collection, sex work, petty robberies and barter of goods and favours – including sexual ones. The historical antecedents of this informal economy can be found in the sites of the shirehkesh-khaneh in the south of the capital or in the gathering of opium users in the Park-e Marivan, a hotspot of popular drug culture in the 1960s discussed in Chapter 2.

Working in these settings meant facing several challenges. The law enforcement agencies (LEAs) represented the most immediate threat to the work of support and outreach in harm reduction. Police operations were a regular feature of the working class neighbourhoods, especially those neighbourhoods notorious for drug dealing (e.g. Khak-e Sefid, Darvazeh Ghar). Their consequences were twofold: firstly, drug (ab)users could be arrested and sent to prison, with all the negative effects on their individual health and well-being. After all, the risk of HIV contagion remained highest in the prison. A longer-term damage was the sentiment of distrust and suspicion that police operations cast on harm reduction programmes.Footnote 43 Drug arrests made the efforts of harm reduction workers difficult and unstable, especially in winning the trust of local communities in favour of an alternative to the punishment model. Given that Persepolis preached a peer-to-peer model, the NGO employed former, or in some cases current, drug users in support programmes. Its objective was not simply to recover the addicts, but to dissipate, through praxis, the stigma of homelessness, HIV and drug (ab)use. This grassroots model fell in line with the state’s approach to social questions, especially with the drug phenomenon. The Ministry of Health, through the expertise network of the UNODC, helped Persepolis establish Iran’s first methadone substitution centre in 2000.

Persepolis was not unique in the harm reduction landscape of the 2000s. Other meaningful experiences emerged from the city of Kermanshah. The outbreak of the HIV epidemic in the city’s major prison pressed the government for an immediate response. The first survey of HIV in Kermanshah took place in 1995. Although the results were not alarming, a member of the Majles from Kermanshah requested the opening of a national AIDS hospital in the city. Once approved, the proposal faced the unwelcoming reaction of the local population, which took to the streets and damaged governmental buildings, impeding the inauguration of the work. Popular opposition to the plan confirmed the top-down nature behind it. Kamiar Alaei, a local physician who, together with his brother, started the first harm reduction activities in Kermanshah, suggests that the government plan ignored cultural sensibilities and people’s perception of the problem. ‘People realised that HIV patients would be referred to the city and Kermanshah would be tagged by HIV’.Footnote 44 The city of Hamadan in Western Iran had had a similar reaction to the establishment of a large mental health hospital (popularly known as timarestan) in the early 1990s. The fear was that it would become the medical centre of all of Iran’s mental health problems, therefore acquiring the fame of the city of the fools.Footnote 45 To cope with the HIV epidemic in Kermanshah, the government needed the support of local groups.

By the year 2000, local authorities in the Kermanshah managed establishing Triangular Clinics supported by the University of Medical Sciences. Triangular clinics provided three kinds of services: sexually transmitted disease testing and treatment; HIV/AIDS testing, treatment, counselling, and housing; and harm reduction materials and methadone maintenance.Footnote 46 Collaboration between the state, the university and local groups sought to respond to the spread of HIV through practical means, starting from the prison population and their families. These two groups had the highest infection rate among all. By relying on civic groups, the government kept out of the thorny business of addiction and HIV. It opened the field for non-state groups to manage the HIV crisis, while it acquired insight into the crisis itself through the knowledge network and information gathering built up by civil society organisations. The Alaei brothers fit this role in every respect. Fluent Kirmanshani speakers, they had been active in the Kermanshah province for several years prior the opening of the Triangular Clinics.Footnote 47 Their project spoke a language, synthetically as much as semantically, familiar to the local population. At the same time, through their affiliation and activism in the medical and drug policy community, they had working connections with the political centre, a fact that legitimated their endeavours in the first years of work.

Like the experience of Persepolis, the Triangular Clinics focused on social perception of drug use and HIV as they attempted to cast away stigma and reintegrate their patients back into their normal lives. In Maziar Bahari’s documentary Mohammad and the Matchmaker, the Canadian/Iranian Newsweek journalist follows an HIV-positive and former injecting drug user in his search for a new wife.Footnote 48 The matchmaker in question is Arash Alaei, the younger of the two Alaei brothers, who has been Mohammad’s doctor for many years. Through his network of HIV-positive people in Kermanshah, the doctor finds Fereshteh, a twenty-one-year-old woman who contracted HIV from her heroin-injecting ex-husband. Tension is palpable in the meeting, but more importantly, the two are willing to show their faces and talk to the camera without shame. By talking to the camera, they also talk to policymakers, make a potential contribution to the cause of HIV-positive people in Iran, and give legitimacy to the civil society projects of the Alaei brothers.

Getting rid of the stigma of drug (ab)use and, especially, HIV was an important passage because ‘the leading cause of death among former prison inmates living with HIV and AIDS was not from AIDS-related diseases but, instead, from suicide’.Footnote 49 Long years of state propaganda and public outcry against drug (ab)users had instilled deep contempt and fear towards them, especially those infected with HIV and those whose drug dependence was visible in public. Stigma represented a harder enemy to overcome. Having HIV meant being cast out of society, with adverse psychological repercussions as well as material consequences. An employer could fire an HIV-infected person for being HIV-positive. Parents could disown their children and deny them support and inheritance rights. Public debates and media rhetoric reiterated feelings of guilt and unfitness of those infected by the virus. At times, the virus itself became emblem of Western moral corruption and corporal destituteness. With stigma alive in the public understanding of HIV, prevention and treatment programmes could not succeed and expand up to required needs. Opposition against harm reduction stayed strong within political pockets, especially among conservatives and security-oriented groups. The general population, for the most, maintained the view of the drug (ab)users as undeserving individuals, with tougher punishment being the only response to drugs.Footnote 50 As such, harm reduction remained unpopular and far from people’s priorities, partly due to the decades-long propaganda against narcotics which accused drugs of all possible earthly evils and partly due to the lack of adequate explanation to the public of what harm reduction meant. Introducing a new language, for a new understanding of social realities, was a daunting task.

Beside the work of civil society groups, other personalities contributed to a change in attitude towards HIV and drug (ab)use. Minoo Mohraz is one of the most significant of all. A leading figure in Iran’s Committee to Combat AIDS and an internationally respected scholar, she worked together with the Alaei brothers in several nationwide awareness campaigns. A regular contributor to the media and a prolific public lecturer, she would spell out, breaking all taboos, the situation of HIV as related to sexual behaviours outside the marriage and to drug injection. In her own words, her mission ‘[was] to bring an awareness of AIDS to every Iranian household through television, newspapers and magazines’.Footnote 51 Her authoritative profile convinced members of the government to promote destigmatising policies. She recalls that in 2003, ‘one of Khatami’s deputies had proposed a resolution that prevented those afflicted by AIDS from getting fired from their jobs, however it was not passed’.Footnote 52 Despite the failure to achieve policy recognition on this particular occasion, the government supported the activities and tactics of civil society groups in the field of prevention and awareness of HIV. In this way, the government partly circumvented the obstacles put in the way by those attempting to slow down the process of social reforms. Newspapers expanded their coverage about HIV stories, dipping down into the human stories of infected people. By casting light on everyday aspects of HIV-positive people, they also succeeded in ‘normalising’ the topic of HIV in the public’s eye and paved the way for the inclusion of HIV-patients into the acceptable boundaries of society.

By mid-2000, Kamiar and Arash Alaei’s efforts expanded into a nationwide programme. The Prison Organisation introduced the Triangular Clinic model inside the prison. The Khatami government was a vocal support of the plan and the Ministry backed it enthusiastically. The international community, too, recognised the efficacy of the Iranian model and awarded the project the ‘Best Practice in HIV prevention and care for injecting drug users’ for the MENA region.Footnote 53 By 2006, the two brothers operated in sixty-seven cities and fifty-eight prisons, cooperating with international organisations (e.g. WHO, UN) and neighbouring countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan) to set up similar programmes in Central Asia and the Muslim world.Footnote 54

Going international was not only a matter of prestige and humanitarianism. Despite the reformist government’s readiness to provide the financial resources for the Triangular Clinics and other prevention programmes, the civil society organisations active during this era understood the importance of being financially independent from the government. With opposition to harm reduction never properly rooted within the political order, a change in government could have proved fatal to the harm reduction process. The flow of money for the projects could have easily been stopped and the scaling up of the programmes would have risked being only piecemeal and, hence, insufficient.Footnote 55 Where all state-led policies and plans had failed, civil society activism and networks succeeded in shaking the status quo, eventually influencing public policy.

Nonetheless, the role of civil society groups should not be overstated. They were neither independent nor autonomous, and their strategy was synchronic with that of governmental plans. Khatami’s push for the entry of civil society in participatory politics also meant that the Islamic Republic could manage (modiriyat) areas of high ethical sensibility through cooperation with non-state groups, such as NGOs. Interaction between government and civil society, which came about in overlapping ways, occurred through intra-societal and clandestine manoeuvrings of public officials, without which the practices of harm reduction (initially underground and semi-legal) would have never seen the light as state policies, regulations and laws. The overlapping of HIV crisis, massive drug consumption and the expansion of civic groups interested in harm reduction enabled the progressive policy shift. I shall now discuss how the state worked through clandestine, off-the-record practices in the field of harm reduction.

The State – Driving with the Lights Off

One should not overestimate the capacity to produce change in the highly resilient environment of Iranian public policy. Opposition to policy reform remained staunch despite the sense of emergency and crisis propelled by the HIV epidemic.

Informal, semi-legal practices of harm reduction coexisted, for the initial years, with a set of regulations that, de jure¸ outlawed them. Criminalisation of drug (ab)users, particularly those visible in the public eye (e.g. homeless and poorer drug consumers), remained steadfast. Policing loomed large over the heads of social workers, outreach personnel and drug consumers seeking harm reduction services. Started in very marginal zones of the urban landscapes of Iran’s growing cities, harm reduction kept working with hidden (to the security state’s eye) and underground programmes. Hooman Narenjiha, former director for prevention and advisor in addiction treatment to the Drug Control Headquarters (DCHQ), claims that ‘in order to approve harm reduction and institutionalise this new approach, harm reduction programmes had to be initiated cheragh khamush, [lights off]’.Footnote 56

Lights off required direction from those in the administration of drugs politics. High and mid-ranking officials in the Ministry of Health, Welfare Organisation, and the DCHQ laid the groundwork for the harm reductionists. From behind the scenes, public officials backed the work of civil society groups, opening a sympathetic space within their own institutions vis-à-vis harm reduction, before harm reduction’s approval in the national legislation. A group of people within the public institutions lobbied in favour of legal reforms in drug policy, while civil society groups pushed the boundaries in practice. Among them, Said Sefatian, former head of drug demand reduction in the DCHQ, played a fundamental role. Over the more than eight years of his mandate at the DCHQ, Sefatian witnessed the country’s rapid shift in favour of harm reduction.Footnote 57 Speaking about the outset of harm reduction during an interview, he said,

It wasn’t easy, I had to bear heavy pressures at the time. Thinking about needle exchange programmes or MMT programmes was controversial. When we started in 2001, in this country, addiction, more or less, was not considered a crime, and it was not considered a disease either … You could open a treatment centre, where you would accept addicts and you provide services to them, and then there would be the police and there would be the officials of the Judiciary, who would simply come to the centre and close it down. They would collect all the addicts. If we had 50 addicts, they would collect all of them, put them on a bus, and arrest them. Sometimes, even the personnel would be targeted and I had to intervene!Footnote 58

This account points to the persistent criminalisation coexisting with the introduction of harm reduction practices. The endurance of security-oriented approaches epitomises deep-rooted elements within state power. Driving with the lights off was the methodology of action in order to escape institutional, ideological obstacles. It was based on the synergy between public officials who supported the promotion of harm reduction and civil society groups operating on the ground. For instance, Bahram Yeganeh, who acted as the director of Iran’s AIDS committee during the reformist period, explains that when there were talks about needle exchange programmes within prisons, the top authorities of the Prison Organisation declared their opposition, but with ‘the collaboration of mid-ranking officials [modiran-e miyaneh] we carried it out, while the upper level was against it’.Footnote 59 The mesostrata of the state acted as a practical ground between civil society and the state, somehow bypassing the formal hierarchy existent in ordinary situations.

Sefatian refers to the actual group of people, within and without the state, whose synergies worked in favour of harm reduction. He refers to this group as an alliance of people who had similar concerns about addiction and shared values in how to respond to the crisis.

There were several reasons why we succeeded. The first was that we had a great team. In the DCHQ, the Ministry of Health’s office for addiction, the Welfare Organisation, the Prison Organisation, the NGOs and in the UNODC … This group had a great alliance, every week we would meet in my office at the DCHQ and we would discuss how to carry out and push forward programmes [towards harm reduction] to respond to the crisis.Footnote 60

This group of people, who belonged to different institutions often in competition with each other, was key in connecting the practices of non-governmental organisations with the judiciary, the policy community in the Majles and the negotiating body with regard to drugs policy, the Expediency Council.Footnote 61 Because the police intervened in many cases to stop the activities of the DICs, Sefatian thought of an expedient, a way to turn this repression into a positive force.Footnote 62 He opted to go public:

As soon as the police would go to make trouble for the DICs and the treatment centres, I would call the newspapers and send journalists to that centre to report on the event. For instance, if Dr [X]’s centre has been targeted by the police, I would immediately call a journalist to report about it and it would be published on the website and on the newspapers.Footnote 63

Through the media, the harm reductionists brought the contention to the public sphere and to the attention of the judiciary and the government. The ‘proximity’ with the often security-oriented judicial authority, in particular, represented another opportunity to introduce the advantages (and values) of harm reduction within the order of state law-making. As Sefatian recounts, once called in front of the Attorney General to explain his remarks about the worsening condition of ‘addiction’, he took advantage of the circumstances to speak about the benefits that Iran could obtain from going all the way forward in implementing harm reduction. His argument was similar to those that the Alaei brothers and Bijan Nasirimanesh used with clerics and ordinary citizens in order to break the taboo of providing clean needles to drug users and prisoners. Although Sefatian did not coordinate his actions and statements with civic groups, and vice versa, the dialogue and exchange of ideas informed their engagement with the higher layers of drugs politics.

This situation generated, ipso facto, a common idiom of ‘crisis’ and a common set of argumentation around it to adopt when discussing reforms and harm reduction with those opposing them, first and foremost with the state. Sefatian’s role and his connections with on-the-ground groups is revealing of the scope of ‘politics from below’ within Iranian public policy. Elements within the governmental machinery operated, persuasively and materially, in order to produce, firstly, practical change in the field of drug policy and, eventually, formal recognition of this change in the laws. Politics from below played along with the HIV epidemics and the shifts towards more dangerous drug consumption patterns in the early 2000s. The harm reduction assemblage made of public officials, informal networks and civic groups built up its own apparatuses of crisis management.

The judicial authority and the clergy as a whole needed to clarify their official stance, and to confront those critics who blamed them for being unresponsive on this issue. To find an acceptable and pragmatic solution, language had to hint at simple wisdom, with a loose Koranic justification: between bad and worse, one is required to opt for bad.Footnote 64 According to the mainstream interpretation of the Koran, if a Muslim’s life is in in danger of death, he or she is required to survive even when survival is dependent on committing sinful acts (haram), such as drinking alcohol if alcohol is the only available beverage in the desert, eating dead bodies if that is the only available food, or providing clean needles to pathological drug users, if that is the only way one can prevent deadly HIV infections for them and their families. Connected to the notion of zarurat (necessity/emergency), which I shall discuss in the next Chapter, this hermeneutical vision allowed the clergy to adopt a flexible position vis-à-vis matters of governance. This further justified reform-oriented approaches to drug laws, for the Expediency Council had already prefigured drug phenomena as part of the state maslahat (interest) and a primary field of management of crisis.

As for the media, the coverage of controversial programmes for addiction had no immediate favourable return for the harm reduction movement. Most of the reportage was negative and critical; public opinion maintained its traditional dislike for drug (ab)users, addicts, as dangerous subjects, associating them with criminal behaviour and moral deviancy. The role of the media, nonetheless, was not aimed at changing, in the first place, public opinion, but at creating a public debate about illicit drug and public health. As revealed by Sefatian himself:

At the time, I took five journalists to come and report on our pilot experiments … Positive and negative coverage played in our favour, regardless of their criticism. Why? Because I wanted to open up the view of the public officials, I wanted to start a public debate about alternatives. And it worked. I noticed that the Majles representatives, the courts and the LEAs had already taken the lead to attack our programmes. On the other hand, some people were praising it, so I moved the fight away from me and I made it public. It was not my personal opinion anymore. It became a public question!Footnote 65

For the harm reductionists, it was crucial to introduce their arguments into the public debate. A famous aphorism comes to mind: ‘the only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about’.

Can this be regarded as a distinguishing method of action in a political environment resistant to change, such as that of Iran? By counterbalancing the soft means of the press and the defiant practices of NGOs, to the coercion of the police and the law, public officials supporting harm reduction opened up a political space for discussion and change. The case in question also defines an established tactic among policy reformers, which has had its precedents in recent history. In 1998, then-director of the DCHQ, Mohammad Fellah, had attempted shifting the way people discussed and thought of addiction. In an interview, he revealed:

In order to change the maxim ‘addiction is a crime’ … I asked the [DCHQ] director for news and communication to give me a journalist so that I could work with him on a series of tasks and I could ask him to do some stuff [sic]. They sent me a brotherFootnote 66 from the newspaper IranFootnote 67 and we went together to interview the Ministry of Interior, the Attorney General … In the meantime, in the newspaper we would write ‘addiction is not a crime’. Then I would ask the Ministry of Welfare to send a letter to the Head of the Judiciary and to ask him whether addiction was a crime or not. The answer was not positive, but we started again from scratch and sent another letter after three months … After we had done this a few times, the attitudes started changing’.Footnote 68

Considering that at the time of this interview, addiction was a crime, Fellah’s expedient is paradigmatic of repertoires entrenched in the mechanism of power and reform. Indeed, it might well be that it was the legacy of Mohammad Fellah in the DCHQ that provided the tools and tactics of action among the harm reductionists, as in the case of Sefatian. Fellah and Sefatian’s tactics exemplify similar acts of politics from below within the policymaking community.

Strategic resistance met opposition to harm reduction; public debates, clandestine connections, semi-formal networks worked in favour of reforms. The use of the media in the policy ‘game’ is a bearer of great significance when contextualised in the mechanisms of power during the reformist governments. It is, in the words of Gholam Khiyabani, the press which carries the burden and acts as ‘a surrogate party’.Footnote 69 Newspapers and journals become the arena for new proposals indirectly (or explicitly) related to a particular political group or faction. It is no coincidence that both NGOs and press publications incremented their output and coverage from Khatami’s election in 1997 onwards. In this regard, one could argue that civil society, too, had become a ‘surrogate party’, an indirect government for the reformist, or to put it more crudely, civil society performed as the government in practice. Support for groups outside government, such as the NGOs, was instrumental to the government itself, for it had the objective to push for reforms otherwise unspeakable by the government itself.

Contextually to the rise of the harm reduction, rogue (more or less) members loosely associated with the anti-reformist camp discredited, accused or, worse, physically harmed several high-profile ministers and officials.Footnote 70 These individuals paid the price for demanding more daring reforms in the political order. Reformism meant that the ‘red lines’ of politics blurred, with the risks and stakes higher than ever. Harm reductionists too faced challenges from those who deemed their push for reforms as incompatible and threatening the Islamic order or the security of the state. On several occasions, the authorities seemed on the verge of turning back and stopping all harm reduction programmes. Gelareh Mostashari, senior expert in drug demand reduction at the UNODC office in Tehran, speaks about it in these terms:

When I was working at the Ministry of Health, the head of the police, which at the time was Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf [former mayor of Tehran and presidential candidate]Footnote 71, wrote a project out of the blue, saying, ‘Let’s bring all the addicts to Jazireh [island] and confine them’. An island! We were talking about harm reduction and he put forward the option of the island? The Qalibaf report became like a bombshell, all those who had disputes under the surface started opposing Qalibaf’s project, and it was consequently withdrawn thanks to the mediation of the DCHQ’.Footnote 72

The diatribe referred to immediately went public in the Tehran-based newspaper Hamshahri on October 22, 2003, with the title ‘Favourable and Contrary Reactions to the Maintenance of High-risk Drug Addicts in Jazireh’, where several members of the DCHQ argued in favour of harm reduction, criticising those who wanted to look backward, implicating Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, then Head of the Police.Footnote 73 Qalibaf had been putting more than a spanner in the NGOs’ works. He repeatedly targeted Persepolis outreach programmes in Darvazeh Ghar, attacked the DIC of another NGO in Khak-e Sefid (an infamous gangster nest in Eastern Tehran) and continued generally to stand against the medicalisation of drug (ab)use.Footnote 74

Harm reduction found itself stranded between health and welfare on the one hand, and law and order on the other. Lack of cooperation between different branches of the state exacerbated the idiosyncrasy of reformism, caught between government and the securitising state. Crisis helped getting out of the impasse, with civil society groups turning to the device of crisis management and its technology of intervention amidst the impossibility of action. This process involved pressures, resistance to diktats, promotion of sympathetic projects and informal connections, including with international organisations, in primis the UNODC.

The UNODC as a ‘Bridge’ between the State and Society

It is not a coincidence that the emergence of the harm reduction discourse took place contemporaneously with the establishment of the UNODC headquarters in Tehran in July 1999. The establishment of the UN office in Tehran was part of the broader rapprochement between Iran and the West, led by the reformist government and the international community. The event was facilitated, partly by the activism of the Khatami government, partly by the EU need to counter the flow of drugs into its territories. The international organisation occupied (and still does) a six-storey building in a busy, commercial area of Tehran, Vanak Square, where it had its headquarters separated from other UN offices. The personnel was mostly composed of Iranian nationals and a handful of foreign experts, among which was the Italian representative of the UNODC. Overall, the office numbered a couple of dozen people operating full-time, in three main sections: Drug Demand Reduction; Drug Supply Reduction; and Crime, Justice and Corruption. On the one hand, the UN had historically provided technical and financial support for the expansion of civil society organisations in the developing world; cooperation with Iranian institutions in the field of drug policy was arguably easier than working in the field of human and gender rights.Footnote 75 On the other hand, the cadres of the Islamic Republic perceived the UNODC as a historically prohibitionist organism, which did not pose strong ideological barriers with Iran’s own prohibitionist discourse. Since 1997, Pino Arlacchi, a well-known Italian sociologist, had been appointed head of the UN anti-narcotic body, with the promise to eradicate or sensitively reduce drug supply and demand within ten years.Footnote 76 To do so, the international organisation needed full cooperation from Iran, which, in turn, was seeking to reignite the diplomatic track at the international level. Iran and the UNODC had prohibitionist credentials and a stake in expanding their collaboration. In fact, they both campaigned around Pino Arlacchi’s (in)famous slogan of the late 1990s, ‘a drug-free world’.Footnote 77

However, the role of the UN body went beyond that of partner in fighting drug trafficking, or, in drug policy parlance, supply reduction. In the Iranian context, the UNODC supported policies which were still taboo in its headquarters in Vienna. While there were discussions about harm reduction in Tehran, with the UNODC coordinating meetings between international experts and national authorities, the Vienna-based body preached a neutralist, if not opposing, stance on harm reduction policies elsewhere. This was specifically due to the United States’ decade-long opposition to harm reduction. As the UN drug control body received most of its international funding from the United States, there was a tacit understanding that UN strategic programmes should focus on the supply reduction side, and downplay harm reduction. In line with that, Antonio Maria Costa, the UNODC high representative, warned that ‘under the guise of “harm reduction”, there are people working disingenuously to alter the world’s opposition to drugs … We neither endorse needle exchange as a solution for drug abuse, nor support public statements advocating such practices’.Footnote 78 So, how can one explain UNODC’s constructive role with Iranian harm reductionism in the light of its overt opposition to harm reduction globally?

The answer needs to look at the strained relations between the United States and Iran during this period, despite the partial defrosting during Khatami’s diplomatic push under the slogan of Dialogue among Civilisations. The text of the Third Development Plan stressed the need to establish foreign and international partnerships in the field of research and development. This was partially successful and, by the turn of the millennium, Iran could benefit from the partnership of ‘various international and foreign organizations, including various developmental agencies of the United Nations such as UNDP, UNICEF, UNFPA, UNODC and UNESCO since 1999, the World Bank since 2000, and the British Council since 2001’.Footnote 79

Lack of diplomatic relations between the United States and Iran signified that UNODC undertakings inside Iran would have to be financed (and therefore influenced) by other countries. It was mostly European money, with Italy (for drug use issues) and the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland (for drug trafficking) that promoted UNODC programme in Tehran. Contrary to UN practice in most of the developing world, the office in Tehran employed almost exclusively national staff.Footnote 80 This had several advantages, in terms of capacity to influence the harm reduction process, and some dangers. Most of the staff had previously worked or researched within state ministries and had an existing network of associates. They had extensive knowledge of the cultural, social and administrative peculiarities of the country. In other words, the staff was acquainted with the red lines of Iranian politics and knew how to, tactically, deal with them. They also had more legitimacy vis-à-vis national authorities, which have been historically (and somewhat correctly) suspicious of foreign meddling into the country’s domestic affairs. Within the UNODC, this also left more leeway of manoeuvring to promote approaches which clashed with US guidelines. On the other hand, being Iranian exposed them to a possible backlash from the authorities, given that drugs was a highly sensitive matter.Footnote 81

Based on these potentialities, the UNODC acquired a status of relevance in a short period and secured an influential role in the faltering and precarious terrain of Iranian drugs politics. In the words of Fariba Soltani, who acted as demand reduction officer at the time, ‘the UNODC functioned as a bridge with the international community, providing contacts and networking opportunities for Iranian national experts. It later facilitated funding for travels to conferences, workshops’.Footnote 82 Then-UNODC representative Mazzitelli confirmed that the leading task with regard to civil organisations was to ‘to bridge, to support and to give visibility and credibility to initiatives’.Footnote 83 The Nouruz Initiative of the UNODC financed two demand reduction projects, Darius and Persepolis, for civil society. The choice of the names bore political significance. The projects were named after key elements of Iran’s pre-Islamic history, which had been mostly ignored, if not opposed, by the governments of the Islamic Republic prior the election of the reformist president Khatami.Footnote 84 The funding promoted the establishment of the DARIUS Institute, focused on prevention programmes, and Persepolis NGO, which provided harm reduction services. Another UNODC official, Gelareh Mostashari notes:

[The UNODC] bridged this movement [jonbesh] with the outside. At the time, I was not working at the UNDOC, but I was involved in the events and processes from my post in the Ministry of Health. It must be said that many of the processes initiated were done by the people inside Iran, but they used the bridge [pol] that the UNODC provided to connect with the outside.Footnote 85

By directly involving the medical community and experts in the field of drug policy, the UNODC managed to establish an informal, yet proactive, forum of debate within the institutions. ‘It was the first time’, Soltani recalls, ‘that we had such a comprehensive discussion about drug policy and HIV in Iran. People were talking around a table, overtly’.Footnote 86 Regularly, civil society groups would take part in these events and would share their bottom-up experience of the drug phenomenon. On some occasions, a triad of medical expertise, grassroots organisations and the UNODC would hold workshops for the NAJA and the Judiciary, advocating for harm reduction measures.Footnote 87 For example, in October 2004, members of the Mini Dublin Group,Footnote 88 the DCHQ and several dozen NGOs participated to a two-day workshop on demand reduction and advocacy. On this occasion, Arash Alaei asked if the UNODC could play a coordinating role between the NGOs and the government.Footnote 89 The bridge of the UN body facilitated communication with state organs, often engaged only half-heartedly in implementing a more humanitarian approach to drug (ab)use.

The UNODC, by means of providing institutional backing for Iranian officials’ country visits, introduced them to alternative models of drug policy and successful examples for the implementation of harm reduction. Among the several country visits that the UNODC supported, Sefatian refers to one visit in particular: Italy. ‘Italy was the first country I visited and looked at in order to change Iran’s drug policy in 2001’, he says and adds, ‘I re-used many of the things I learnt in Italy from their experience for our work in Iran’.Footnote 90 The role of Italy in mediating between Iran’s bid on reformism and the international community was not coincidence. When the United Nations inaugurated the year 1999 as the Year of Dialogue among Civilisations – giving clout to president Khatami’s diplomatic effort – Giandomenico Picco, an Italian UN official who had been, inter alia, behind the negotiations of the Iran–Iraq War and US hostage crisis in Lebanon, was nominated the Personal Representative of the Secretary General for the United Nations Year of Dialogue among Civilizations.Footnote 91 The UNODC representative Antonio Mazzitelli suggests indeed that ‘it was not Italy perhaps, but Italians that activated a channel of communication between Iran and the international community during the reformist period. Drugs were part of a bigger, ongoing dialogue’.Footnote 92

In the early 2000s, Iran obtained international support for its pilot harm reduction plan, which, in turn, convinced the authorities that the right path had been taken. Given the fact that one of Khatami’s greatest concerns was international recognition, international cooperation in the field of drug policy was all the more significant and welcomed. The UNODC had created the neutral venue for civil society and state officials to share ideas and promote new strategies. The prestige of collaborating with the United Nations added legitimacy and strength to the voice of the participants.Footnote 93 In drug matters, cooperation with the international order seemed easier and more productive. Many believed it could be a model in other fields in which Iran sought recognition and rapprochement.

The establishment and consolidation of diplomatic ties with international partners is among the most effective – and yet short-lived – moves that the Khatami government undertook. The relationship with the international community in the field of drug diplomacy not only enhanced the chances for a progressive move domestically, it also resulted in being a durable and solid element of cooperation between Iran and the rest of the world, even during the darkest periods of Iran–West confrontation, namely after US president George W. Bush’s ‘Axis of Evil’ speech. Khatami’s Dialogue among Civilisations was built mostly through intellectual fora and through symposia, but its most practical achievements were in the field of international cooperation on drug control and drug trafficking which were of immediate concern to Iran’s European counterparts, more than Khatami’s philosophising interpretation of civilisation and religions.

Conclusions

As the reformist government initiated a reflexive moment with regard to the role, reach and regulations of the state, it also acknowledged the limitations proper to the agency of its government, which were also due to the conflictual nature of inter-institutional dynamics during the period 1997–2005. The lost hegemony of state apparatuses, on the one hand, brokered an opportunity for ‘co-regulation’ and pilotage in tandem with civil society organisations.Footnote 94 The flow of opium, first, then its sudden drop, coalesced with the increase of injecting as a mode of consumption, which in turn contributed to the spread of the virus HIV. The drug assemblage constituted by the multiple crises around illicit drugs – health, ethical, social and political – opened up opportunities for co-working between competing apparatuses. Informal civic workers, medical professionals, prison officials, international donors, bureaucrats and politicians were all part in the great game of drugs politics. Their inroads, often informal if not illegal, enabled change by practice and, finally, recognition of reforms. The developments of the reformist period, in fact, did not result from the enunciation of governmental policies ‘from above’. The government never took the lead in changing the content of drug control programmes. Instead, a pluralistic alliance of diverse groups, which acted not always in coordination with each other and rarely in overt political terms, took the lead. This secular alliance introduced the spark of change, lobbied for it and secured the support of public officials and key regime stakeholders. From this perspective, one can see why and how civil society was the leit motif of the reformist era.Footnote 95

This assemblage of groups that belonged to different public and private organisations, including state representatives, medical experts, NGO workers and activists as well as international donors, contributed to the birth of the harm reduction system in a matter of less than a decade. Diachronic to this synchronic moment – the ‘great team’ referred to by a drug policy official – was the phenomenon of drugs and addiction in Iran, itself the result of global changes in the drug ecosystem. First with the ban of opium by the Taliban and then with its unprecedented expansion in the wake of the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, the Iranian state experienced a transformative and unpredictable reality to which it responded through a combination of security measures and technical knowledge. Both, one could argue, defied the image of the Islamic Republic as a religiously driven political machine and, instead, categorised a governmental approach, which adopted profane means and a secular mindset in dealing with issues of critical importance, with crises.

The making of the harm reduction policy is situated in a grey area between formal state institutions and societal (including international) agents. The case of harm reduction elucidates otherwise shady mechanisms of formulation of (controversial) policies, while also revealing meaningful aspects of Iran’s governmentality on crises. Crisis is an ordinary event in Iranian politics. Partly, the perpetual crisis is contingent of the revolutionary nature of the Iranian state; and partly, it is a loophole to quicken or slow down the process of reforms. President Khatami, whose government adopted the idiom of ‘reforms’, described his mandate as a period during which the government faced ‘a national crisis every nine days of government’.Footnote 96 His reforms, too, adopted the idiom of the crisis, especially in the field of drugs policy.