Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- 1 The decline of Indonesian Democracy

- Part 1 Historic al and Comparative Perspectives

- Part 2 Polarisation and Populism

- Part 3 Popular Supp ort for Democracy

- Part 4 Democratic Institutions

- Part 5 Law, Security and Disorder

- Index

- Indonesia Update Series

13 - A state of surveillance? Freedom of expression under the Jokowi presidency

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- 1 The decline of Indonesian Democracy

- Part 1 Historic al and Comparative Perspectives

- Part 2 Polarisation and Populism

- Part 3 Popular Supp ort for Democracy

- Part 4 Democratic Institutions

- Part 5 Law, Security and Disorder

- Index

- Indonesia Update Series

Summary

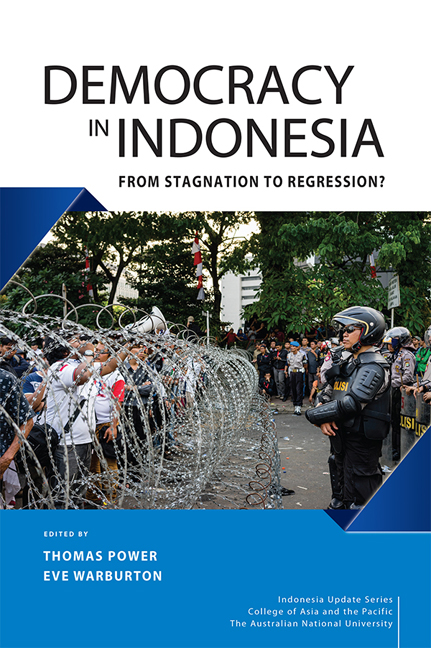

In May 2019, following the official announcement that Joko Widodo (‘Jokowi’) had been re-elected for a second term, supporters of his rival, former general Prabowo Subianto, took to the streets. While these protests were unlikely to alter broad public acceptance of the election results, they prompted a strong response from the Jokowi government. This included the large-scale mobilisation of security forces, mass arrests of demonstrators, and the blocking of video and image sharing on social media and messaging platforms such as WhatsApp.

Government representatives justified the actions by referring to national ‘interests’ and ‘security’. Communications and Information Technology Minister Rudiantara stated that the restrictions on social media were imposed to contain the spread of fake news, hoaxes and provocative content that could prompt clashes between Prabowo supporters and security personnel. Other cabinet members, including Wiranto, the coordinating minister for politics, law and security, similarly argued the restrictions were born of necessity: ‘[for] three days, we won't be able to look at pictures. I think we’ll be fine. This is for the national interests’ (Kure 2019). After the protests had ended, Rudiantara suggested the police should be given the power to monitor WhatsApp. He dismissed concerns of civil society groups who argued that such monitoring would violate privacy rights. Rudiantara received support from presidential chief of staff Moeldoko, who said that national security should be prioritised over individuals’ privacy (Lee 2019).

This case reflects a broader trend towards increasing limitations on the freedom of expression under the first term of Jokowi's presidency (2014– 2019). The Jokowi administration's limited interest in civil and political rights has been well noted (McGregor and Setiawan 2019). In the early years of Jokowi's presidency, analysts attributed this apathy to Jokowi's prioritisation of economic programs and the need to consolidate his initially weak political position by accommodating conservative political forces (Muhtadi 2015; Warburton 2016). But these trends only intensified as Jokowi secured his hold on power: by late 2016 he had consolidated his political position, yet the government's protection of civil and political rights continued to deteriorate.

These developments are further evidence of what Diprose et al. (2019) describe as an ‘illiberal turn’ in Indonesian politics.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Democracy in IndonesiaFrom Stagnation to Regression?, pp. 254 - 274Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2020