The previous chapter examined reports of obeah trials largely from the point of view of state activity. It investigated the process of prosecution and showed how legal practices and agents of the state contributed to the dominance of a concept of obeah as bounded by specialist–client interactions involving financial exchange. Within the parameters established by law, however, the trials also reveal much more. We have seen that trials worked within a legal framework that produced an emphasis on rituals, money, and objects, but we have not yet considered the nature of the rituals, the process of transfer of money, or the kinds of material objects that were used in trials. Nor have we investigated the meanings of the practices that led to trial from the point of view of those engaged in them. In this chapter, then, I look more closely at the evidence gathered from obeah trials. The prosecutions do not allow us to define what obeah is or was. But they do enable us to build a rich picture of the range of activities undertaken for the purposes of spiritual and ritual healing in the early twentieth-century Caribbean, and to investigate how these related to one another and to the law. The evidence presented in obeah prosecutions demonstrates the fluidity and multiplicity of healing and spiritual work. It reveals the influence of concepts of the power of the dead that resonate strongly with what we know about African understandings of the ancestors, conjoined with magical techniques that drew on long-standing European traditions, all naturalized within the Caribbean. Meanwhile, these traditions jostled with and interacted with recently invented curative practices such as homeopathy, electrical healing, and mesmerism. The most significant concept informing Caribbean spiritual work was that the spirits of the dead, known as duppies, jumbies, and ghosts, influenced the world of the living. This idea can be discerned in many of the techniques for diagnosis and healing displayed in the records of arrests and prosecutions for obeah. But much else is to be found in these trials as well. This chapter also examines the social position of individuals prosecuted for obeah, the role of place in ritual practice, the reasons that people consulted obeah practitioners or those perceived as obeah practitioners, the interpretations made by spiritual workers, and the range of ritual techniques they employed.

The prosecutions also suggest some pan-Caribbean practices, enabling us to distinguish them from the locally specific. Certain techniques found regularly in Jamaica never appear in the Trinidadian material, and vice versa, but much of what appears in the trial records was present in some form across the Caribbean. Similarly, the material reveals the evolution of ritual practice over time. Some techniques found regularly in nineteenth-century cases are almost never present in the twentieth-century sources, while new methods and interpretations are found in the twentieth century that had not previously existed. The most notable innovation is the use of published books, especially those produced by the DeLaurence company in Chicago.

In this chapter I seek to use, as historians frequently do, evidence that was created in the process of legal attacks on people to write about those people's beliefs, practices, and relationships. This is a necessarily difficult task. The prosecutions mediated through newspaper reports that provide the evidence used in this chapter were conducted in a context in which there was already a strong stereotype of the obeah practitioner. Decisions about whom to prosecute, the likely success or failure of those prosecutions, and the discourse through which they were reported all drew on that stereotype, while also reaffirming and developing it. Thus to use the evidence of reports of prosecutions to learn about the meanings those prosecuted ascribed to their practices risks several naïve assumptions: that there was a reality ‘behind’ the prosecutions that existed separately from them, and that this reality can be disentangled from the evidence produced by the prosecutions. We need to avoid using the court cases in the same way as did the colonial state, as a means of homogenizing the range of healing practice that existed in the Caribbean and of condensing a wide range of everyday activity into a singular object, ‘obeah’. And yet not to use the richly detailed evidence produced by the prosecutions to extend our knowledge of everyday practices of healing would also be a loss. It would wilfully close to us a layer of evidence about the conflicts, struggles, and meanings of everyday life in the Caribbean, and would reinforce a focus on the discourse of the elite. The evidence from the newspapers, while partial, does give us information about the ritual practice of those prosecuted for obeah and the people who turned to them for help, including the problems they sought help with, their understanding of harm and how it was caused, and the materials, words, and actions they employed. To find evidence about obeah that is comparable in depth and detail to that collected from the newspapers, we have to turn to anthropological studies of Caribbean ritual healing work.Footnote 1 These, although they have some important advantages over material collected through newspaper reports of prosecutions, did not begin until the mid-twentieth century, and never produced the volume of evidence gathered here. In order to avoid the assumption that prosecution evidence gives us direct access to the meaning and experience of Caribbean ritual practice, while still learning as much as we can from it, in this chapter I analyse the evidence of prosecutions in the light of the stereotype of the obeah practitioner, paying particular attention to the points at which practices recorded in the prosecution evidence seem to depart from that stereotype.

The stereotype of the obeah practitioner established during slavery persisted with little change into the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A good example appears in ‘The Obeah Man’, the winner of the Gleaner's Christmas short-story competition for 1896. The story is narrated by a police inspector who seeks out an obeah man who is sheltering a murderer. The obeah man lives in a remote ‘mud hovel’ on a mountainside, with soot-blackened interior walls hung with reptiles and bats. He is a ‘most hideous old African’, with ‘shaggy white eyebrows’ and ‘shrivelled lips.’Footnote 2 This fictional obeah man differs little from slavery-era obeah men such as Amalkir in William Burdett's Life and Exploits of Mansong or the ‘wrinkled and deformed’ Bashra of William Earle's Obi, who lives in a ‘sequestered hut’, both of whom drew on Benjamin Moseley's description of obeah practitioners as ‘ugly, loathsome creatures’ who were inhabitants of ‘woods, and unfrequented place’.Footnote 3 The 1896 story's obeah man is also a descendant of the mid-nineteenth-century character Fanty in Mary Wilkins's The Slave Son, who also lives in a remote location and is physically grotesque.Footnote 4 Fictional obeah practitioners of the stereotyped kind found in this story and in its precursors were almost always solitary individuals of African descent who lived in isolated rural cabins or caves. They were elderly men, frequently physically repulsive. Their practice is drawn from generic African traditions, and has no hint of Christian theology or ritual. Such obeah men continue to appear in twentieth-century Caribbean fiction, most notably Claude McKay's Banana Bottom (1933).Footnote 5 A few individual fictional characters, such as Hamel in the eponymous novel and Feruare in Earle's Obi, were more complex, but the composite stereotype of the obeah man was of someone amoral or evil, willing to cause harm when asked to do so, and making use of mysterious and spooky techniques of power, with an element of Gothic and an association with violence.Footnote 6 In the Gleaner's prize-winning story the police inspector at one point fears for his life as the obeah man approaches him with a knife, although it turns out he only wants a few drops of blood to put in a magical charm.

The stereotype of the isolated obeah man implied a Caribbean that was apart from the rest of the world, separate from the sense of modern life that was so much part of the consciousness of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet the Caribbean has since the early seventeenth century been intensely connected to other parts of the world through forced migrations and trade, the site of ‘landmark experiments in modernity’, as Sidney Mintz explains.Footnote 7 At the turn of the twentieth century the connectedness of the region to places elsewhere was reinforced by the intense intra-regional mobility of the circum-Caribbean population. Drawn by US investment in banana and sugar plantations in Central America, Jamaica, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, the discovery of oil in Trinidad and Venezuela, and the construction of the Panama Railroad and later the Panama Canal, tens of thousands of Caribbean people in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries moved around the region, often moving several times, producing extended networks of knowledge, sociability, and kinship.Footnote 8 As Lara Putnam points out, Caribbean ritual and spiritual practice was reconstructed within this mobile matrix; obeah, she says, was a ‘ritual complex created by, for, and about people on the move’.Footnote 9 Many of the ritual specialists prosecuted in the early twentieth century had lived in two or more colonies prior to their arrest. Their clienteles, some of which were quite extensive, often included people from overseas.

Circuits of mobility in ritual practice followed those of Caribbean labour migration, in which there were two major migratory networks. Trinidad was an important node within a southern Caribbean circuit involving Guyana, Grenada, Barbados, and Venezuela, while Jamaica was part of a partially overlapping northern Caribbean circuit that involved movement to and from Cuba, Haiti, Central America, and to some extent British Guiana.Footnote 10 Many defendants in obeah trials had moved from smaller islands in the Eastern Caribbean to larger, more industrialized colonies, such as Trinidad. Samuel Benkins, who described himself as a bush doctor and said he could divine the source of illness through a ‘gift from the Gods’, was prosecuted for obeah in 1913 in Barbados. He had previously lived ‘in Tobago, Trinidad, Demerara, Grenada, and other places’. In court he produced a long list of people he had effectively treated.Footnote 11 Those moving around the southern migratory circuit had relatively little contact with Jamaicans, who mostly followed the northern routes. In Jamaica, obeah defendants frequently reported previous residence in Costa Rica, Panama, Haiti, or Cuba. Dewry Williams, an ‘elderly black man’ prosecuted for obeah in 1930 after an encounter at Kingston race course, had previously lived in Cuba.Footnote 12 According to the testimony of a policeman, George Washington Pitt had offered his ritual services with the claim that he had ‘learned his trade in Panama’.Footnote 13 William Fraser and Citira Reid had originally met their client Margaret Davis when all three were living in Costa Rica.Footnote 14 Others had spent time in the United States.Footnote 15 Knowledge and connections were made and sustained through movement, often over long distances.

Transnational connections were sustained through the circulation of letters. Theophilus Dascent of Nevis was said to have received letters from people ‘far and near’, including one from Tortola.Footnote 16 David Compass was arrested in Jamaica in 1915 with letters from Haiti and Canada on his person.Footnote 17 Herbert Brathwaite, who was said to be keeping an ‘obeahism house’ in Port of Spain, corresponded with people in England.Footnote 18 Many more ritual workers used the postal system to communicate with clients within the colonies in which they lived.Footnote 19 Dr Williams, who lived in Siparia, Trinidad, was originally from Grenada; letters from many clients thanking him or soliciting further help were read out in court at his 1910 trial for obeah.Footnote 20

Yet while mobility is crucial in understanding the social world in which obeah practice took place in this period, rootedness was also important. Ritual practice was often deeply connected to particular physical locations. Specific places – sometimes small islands and isolated villages, but also symbolically important urban sites – could gain ambivalent reputations, among elites and popular classes alike, as centres of spiritual power. For instance, the St Kitts acting inspector of police commented in 1906 that obeah still ‘flourished’ in Nevis, which he described as ‘always a hot bed of superstition’.Footnote 21 Melville Herskovits's field notes from his 1939 research in Toco, a village on the north coast of Trinidad, relatively close to Tobago, record his informant Margaret's comment that knowledge of obeah (Herskovits used the spelling ‘obia’) in Tobago was especially strong.Footnote 22 The connection between spiritual authority and place goes beyond this discursive or imaginative level, however. First of all, enduring social relations and face-to-face interaction with people were essential for successful ritual practice. These called for a sedentary lifestyle instead of frequent relocations. Given the illegality of their practice, ritual specialists attracted clients by word-of-mouth augmentation of their reputation and authority, and often expected references from people who sought to consult them for the first time. Large clienteles such as that of Dr Williams and other successful ritual workers could not have been sustained by highly itinerant practitioners. In other words, being settled in a particular address for long enough was a prerequisite for popular practice, and the accumulation of social networks stretching across colonial borders added to the credibility and authority of Williams and his colleagues.Footnote 23

Against the evidence of the significance of mobility and long-distance connections to the formation and organization of obeah practices, the stereotype of the isolated practitioner continued to influence the lawyers, magistrates, police, and witnesses who participated in obeah trials, and thus the evidence through which we try to discern the meaning of obeah for ordinary Caribbean folk. This stereotype's influence on everyday trials can, paradoxically, be seen most clearly in cases that diverged from it. One magistrate explicitly contrasted his expectation that obeah defendants would be ‘the admitted obeahmen, the old Africans’ with the reality that the defendant in the case he was trying was a migrant from Panama, or, as the magistrate put it, one of ‘you fellows who come here and want money’.Footnote 24 Similarly, at the 1944 Jamaican trial of Thaddeus ‘Professor’ Brown, the magistrate contrasted Brown's practice of reading a glass of salted water in order to diagnose a problem with what he understood to be typical obeah cases, characterized by ‘sprinkling of blood on a white rooster, scattering of rice and speaking in an unknown tongue’.Footnote 25 As we will see, the magistrate was not wrong to note the prominence of sacrificial roosters, rice, and the ‘unknown tongue’ in obeah cases. But in highlighting these characteristics of trials, he overlooked a range of other practices that were also typical of the rituals and materials in obeah trials, but did not conform to the long-standing stereotype of what obeah practitioners did.

A second stereotype of the obeah man, that of the obeah practitioner as swindler or fraud, existed alongside the idea of the old, isolated African. A few individuals prosecuted for obeah or obeah-related offences do seem to have conformed to this image and were actively defrauding vulnerable people out of their money. Many of these seem to have preyed on the fears, insecurities, and desires generated by the intense mobility of the early twentieth-century Caribbean. Particularly targeted were people who were either about to travel abroad or who had recently arrived in a new place. A series of cases took place over several years in which people were approached within a few blocks of each other in downtown Kingston: on King Street, Duke Street, Orange Street, Barry Street or Tower Street.Footnote 26 Several similar cases took place in Port of Spain as well.Footnote 27 These cases differed from most in that they did not involve entrapment, or a long-standing relationship gone wrong. Instead, witnesses reported that they were approached on the street by people who claimed to recognize them from overseas, or to be able to help them with information about their intended destination. The people or person who approached them then took them somewhere private, where they conducted a ritual that involved the transfer of significant amounts of money for ‘luck’ in their travels, often with the promise that the money would be returned. Others told stories of ‘Spanish Jars’ filled with gold and protected by spirits on people's land, often claiming to have learned how to locate and unearth these while overseas.Footnote 28 These individuals were often tried for larceny rather than obeah, but their trials usually referred to obeah.

William Samuels, for instance, described in court how in 1919, during the Cuban sugar boom known as the ‘Dance of the Millions’, he had come from western Jamaica to Kingston with the aim of travelling on to Cuba for work. In Kingston he met a man who said that he knew someone who could give him information about Cuba. The man then took him and two others to a private house where he introduced each of them in turn to Charles Johnson, who, a later trial revealed, also went by the alias Colon, suggesting his connection to other migratory circuits. Johnson persuaded Samuels to hand over £5, which he placed in an envelope over a glass, then appeared to burn the envelope and its contents. He placed ash on the sole of Samuels's foot (his ‘foot bottom’), and told him that he would get the money back, and more, in nine days. Samuels became suspicious and demanded his money back; when Johnson would not return it, he went to the police.Footnote 29 I was unable to find a report of the outcome of this case, but two years later Johnson was in court again for a very similar incident. Again, it involved a man from western Jamaica who came to Kingston on his way to Cuba and met Johnson, who claimed to be able to give him information about Cuba. Johnson again conducted a ritual that involved placing money in an envelope and set it on fire, and told his victim that he would receive it back later. This time Johnson received a sentence of three years for larceny, and it was revealed that he had nineteen previous convictions.Footnote 30 Ten years later a similar trick involving the apparent burning of money inside an envelope was still taking place in downtown Kingston and still targeted people involved in migration: Gilbert Morais and Justin McGrath were imprisoned for seven years for larceny, having convinced a man who had just returned from Cuba to hand over £70 which he believed they then burnt in an envelope, promising that he would find £20,000 in his trunk a few days later.Footnote 31 In Port of Spain a similar case involved Jordan, a migrant from Tobago who had come to the city to look for work, and met a man at Marine Square (now Independence Square), near the docks. The man took him to see a friend, Budsey Williams, who he said could ‘work’ for him to ensure that he found and kept a job, but then disappeared once Jordan handed over money.Footnote 32 Such cases suggest the vulnerability of both potential and returning migrants, isolated in a city that they did not know well, and anxious about what the future might bring.

Yet if some individuals clearly did take advantage of others’ hopes and fears to trick them out of money, they were a small proportion of the overall group of people prosecuted for obeah and related offences. Even fewer individuals prosecuted for obeah fully conformed to the stereotype of the sinister, isolated old African obeah man. Even those who in some respects seemed to fit the traditional picture diverged from it in other ways. Walter William Christian, for instance, did indeed appear to be an amoral individual prepared to do harm as well as to heal; he was alleged to have said, ‘I can pull, and I can put’ – that is, he claimed both to be able to cause harm through spiritual means and to remove harm caused by others’ spiritual work. But, far from living in a remote isolated community, he had worked for the United Fruit Company in Costa Rica, where he had lost a leg in an industrial accident.Footnote 33 Goopoul Marhargh also seemed to conform to the stereotype of the sinister obeah man, in that he offered to kill the enemies of his client, who were ‘keeping him down’. But he also diverged from it: he was not an African or of African descent, but was described as a ‘coolie’.Footnote 34 In another case the Port of Spain Gazette reported that the defendant, Daniel Young, lived in a ‘small cottage hid away in the heart of a lonely area, with nothing around but dense foliage’ – apparently a stereotypical obeah practitioner par excellence. Yet at his trial it was revealed that Young received letters from clients all over Trinidad, used books acquired by mail order from Chicago, and helped at least one client get a better job in the department of education.Footnote 35 He was thoroughly integrated into the modern, transnational life of the Caribbean. The Gazette's easy recourse to a language that located Young as hidden, mysterious, and isolated, despite these other elements, reveals the power of the discourse about obeah.

If those prosecuted for obeah rarely conformed fully to the image of the isolated, evil, or amoral obeah man, how did the practice of Caribbean ritual specialists work? What were their goals and aims? Why did people seek them out? The information in obeah trials allows for at least partial answers to these questions, although we must recognize that events and interactions that led to prosecutions represent only some of the ritual healing encounters that took place in the Caribbean. The next section of this chapter unpacks what the newspaper evidence tells us about some of the commonalities that underlay ritual practice, while the last part emphasizes the diversity of contexts in which people worked.

People turned to ritual specialists to deal with the full spectrum of human problems. Saying more than this is complicated by the fact that so many of the cases were entrapment stings, in which the individuals seeking help invented problems in order to provoke the suspect into committing the crime of obeah. This was especially the case in Trinidad, where more than half of obeah prosecutions collected were produced by entrapment. As a result, the cases serve as an echo chamber, amplifying the patterns that people embodying the everyday state – low-level police officers and their informants – expected would be plausible reasons for a person to seek ritual help. Some apparently frequent reasons for turning to obeah practitioners appear to be almost entirely artefacts of entrapment. For instance, at first sight it appears that the most common reason people sought out ritual specialists in Trinidad was to resolve problems to do with employment: to get, or to keep, a job. Looking more closely, however, sixteen of the twenty-one cases of this kind were accomplished through entrapment, so what we are really seeing is that those who set up entrapments thought that approaching a suspected obeah practitioner with a story about employment problems would be plausible.Footnote 36 If we exclude entrapment cases, including those involving professional informers rather than police officers, we find that prominent reasons for consulting a ritual specialist included court cases (both civil suits and criminal prosecutions); improving the prospects of a business such as a shop or higglering business, especially when it was doing badly; and problems in relationships (especially men's and sometimes women's desire to keep a partner who was thought to be straying). Some of the myriad circumstances in which people sought ritual help included a person who could not successfully raise livestock, a man who needed to get his driving licence, and a butcher who was being prevented from making sales by a spiritual obstruction.Footnote 37 Overall, the most common reason for consulting an obeah practitioner in both Trinidad and Jamaica, by a considerable margin, was for concerns to do with physical and mental health. The wide range of problems for which people sought ritual help implies something that was also frequently stated outright: that one's overt problems in employment, business, relationships, or health were mere symptoms of an underlying spiritual affliction.

In most of the cases where individuals sought help with their health, the newspaper reports provide little information about the nature of those problems. Reporters generally revealed only that the person was sick, ill, or in pain. Those that do give more information, however, cluster in a few important areas: abdominal pain or disturbances; poor vision or blindness; sores, pains, swellings, or worm infestations in the feet or legs; and mental health problems. In most of the last group of cases it was family members, who described their relatives as insane or mad, rather than the patients themselves, who sought out the ritual specialist. These four clusters may have been the health problems that biomedicine was particularly poor at dealing with – although they may also simply be an inventory of some of the most commonly causes of ill health in the region. Certainly, the cases reveal overlap between the use of ritual specialists and of biomedicine. Many clients stated that they had previously consulted a biomedical practitioner who had not been able to help them – a phenomenon also noted in studies of contemporary Caribbean health culture.Footnote 38 A Guadeloupean woman convicted of obeah in Dominica was said to specialize in ‘the cure, by occult means, of sick persons who had failed to obtain relief from duly qualified medical practitioners’.Footnote 39 Hubert Satchell, in Jamaica, was arrested for attempting to heal a man who had attended the Kingston public hospital eleven times over several months, without improvement in his condition.Footnote 40 Ephraim Napier also attended the hospital when he began to go blind, but, on realizing that its staff could not heal him, sought help from John Wright. Wright told him that his eye problems were caused by an evil spirit, perhaps a more convincing explanation in a context in which biomedicine was unable to provide much help.Footnote 41

The move from biomedical healer to ritual specialist was sometimes stimulated by the sick person concluding that biomedicine had failed because their problem had a spiritual cause. This seems to have been why Iris Cross, who was hospitalized in Port of Spain when she became sick after childbirth, eventually discharged herself. After three days in hospital, and with ‘no sign of improvement’, her ‘reputed husband’ took her home and sought treatment from another healer, because Cross believed that her problems were caused by spirits that her aunt had put on her.Footnote 42 Like Cross, some people arrived at a ritual specialist having already concluded that they were bothered by a duppy, ghost, or hostile spirit. In one case a woman who had been having ‘fits’ saw a dispenser, who advised her that ‘three duppies were on her’ and she therefore needed to be treated by ritual specialists who were skilled in removing duppies.Footnote 43 More often people simply reported their difficulties to the ritual specialist, although the very fact that they approached (or accepted the approaches of) a ritual healer suggests that they at least suspected that a spiritual cause underlay their problems. On some occasions it seems that spiritual workers immediately knew that the problem was caused by ghosts or spirits without needing to investigate. In others, ritual workers used diagnostic techniques, which varied by place.

Descriptions of diagnostic and curative techniques reveal an overlapping ritual complex found in both Jamaica and Trinidad, as well as elements that were specific to each location. In Jamaica, but not in Trinidad, ritual specialists frequently used a procedure they termed ‘eyesight’. Healers would ask for a coin ‘for his (or her) eyesight’ or to ‘clear his/her eyesight’.Footnote 44 This technique anticipates a method analysed by Edward Seaga in 1969, based on his work with Revivalists. Seaga described a popular Jamaican means of determining the nature of a person's problem, involving ‘reading a glass of water into which a silver coin has been placed. The glass is set near a candle, or in the sun, so that the light reflects in the water. The operator then concentrates on the coin visually until it separates into two images, at which time the impression or message is received [from the spirits].’Footnote 45 Seaga did not use the term ‘eyesight’, but his description closely echoes those found in the many Jamaican trial reports that used that term. Several reports described ritual specialists who placed coins presented for ‘eyesight’ in glasses of rum or water. Joseph Telfer, for instance, put a ring of his own, along with a 2-shilling coin from his client, in a glass of rum; the newspaper report noted that the coin ‘was called Eyesight’.Footnote 46 George Williams also asked his client to place 2 shillings in a glass ‘as an “eyesight”’.Footnote 47 A report of the 1929 trial of James Campbell provides one of the most detailed of these descriptions. A witness, Jeremiah Johnson, testified that Campbell ‘filled a glass with water and ordered him to put the 9/ in it’. Campbell then lit a candle, then – just as Seaga would describe forty years later – ‘passed the glass around the candle three times’ while he ‘talked in an unknown tongue’. Having done this, Campbell interpreted Johnson's situation to him, telling him that ‘a man has spent £15 on you five is left and when it is paid you are going to steal and it mean handcuff’.Footnote 48 Contrary to Seaga's evidence, however, in the early twentieth century ‘eyesight’ was used not just as a diagnostic or ‘reading’ technique but also frequently took place after the healer had provided an initial interpretation of the problem. It functioned as a means to cure as well as to diagnose. Eyesight was a routine part of ritual practice in Jamaica, to the extent that it was well known to the magistracy: one magistrate enquired of a witness ‘did he not clear his eyesight’.Footnote 49 The courts were particularly interested in eyesight because it involved the transfer of money and could thus be interpreted as a means by which the practitioner worked ‘for gain’. However, eyesight was clearly more than a means of payment.Footnote 50 In many cases a relatively low-value coin was given for eyesight, and a larger additional payment was also made. Thomas Stewart, for instance, requested 4 shillings for eyesight. However, for the full ‘job’ of removing the damage that had been done by rivals to a couple's market-trading business, he asked for £6, including an initial payment of 40 shillings.Footnote 51

Eyesight was a common technique in Jamaica, but I found no evidence of its use in Trinidad. Although there was a great deal of communication across different parts of the Caribbean, Jamaica and Trinidad were involved in different migratory circuits. Relatively little exchange of knowledge about ritual practice and techniques seems to have taken place between them.

A diagnostic technique shared by ritual specialists in both Jamaica and Trinidad involved packs of cards, presumably imported. Spiritual workers often opened a session by shuffling or cutting cards and either selecting one themselves or asking the client to do so, then interpreting the chosen card or cards. In Jamaica this method might be used in combination with ‘eyesight’, or as an alternative to it.Footnote 52 Daniel Smyth cut a pack of cards, from which he drew a black card, which led him to explain that ‘he could do no good as the child had gone bad and the black card shewed that death had passed over her already’ because a ‘ghost had mingled with the child’.Footnote 53 Picture cards had particular interpretative value. Catherine Thomas, in Trinidad, had a client pick out two cards from several piles. The queen of clubs, she said, signified his wife, while the queen of spades denoted ‘a bundle of troubled spirits, bad devils and young spirits’.Footnote 54 In a Jamaican case a defendant was said to have pulled out four queens from a pack of cards, interpreting them as indicating that four women were interrupting his client's ability to sell at market.Footnote 55 William Hall interpreted the jack of clubs to mean that a ‘black man…had obeahed the boy's leg’.Footnote 56

As well as ordinary playing-cards, some practitioners in both colonies used packs of specially printed tarot-style cards. The earliest example of these appears in a 1909 Jamaican case, where William Bruce drew a card with a picture of a man with a walking-stick and told his client: ‘After I have finished my work you shall walk like that man – in the street.’Footnote 57 Edith Cook made use of cards with pictures of insects, snakes, cats, and dogs, as well as people in various poses, to tell Miriam Hinds which of her acquaintances were in fact her enemies.Footnote 58 Nathaniel Stephens used a pack of cards with pictures of people which he interpreted. In the case that led to his prosecution he showed his client a card with a picture of a ‘girl’ on it, interpreting it as ‘a sign of madness meaning to say his wife was mad’. Another card, which showed the devil with two people, was ‘the two duppies upon your wife’, while a third card with a picture of a girl with her clothes torn off revealed ‘what your wife going to do’.Footnote 59 These interpretative strategies appear to share much with European traditions of card reading, both of regular packs and tarot. There is little evidence about wider Caribbean interpretations of the uses of cards, but in Europe, and especially in Britain, tarot was widely thought to be of Egyptian origin, perhaps revealing a convergence between contemporary fascination with Egypt and Africa in the Caribbean and in Europe.Footnote 60

As these examples suggest, the diagnosis that widely varying problems were caused by hostile spirits or ghosts was ubiquitous. The significance of the spirits of the dead in the lives of the living indicates continuity with the period of slavery. Such a diagnosis was usually revealed when evidence of any length was reported. The spirits were often described as almost tangible, physical beings. Although they could only be seen by the ritual specialist, they used physical means to do harm. Joseph Miller, for instance, examined a young woman with a baby before revealing that she was being harmed by two spirits, also a woman and baby. The adult spirit was ‘blowing’ food served to the woman, making it indigestible, while the baby spirit was sitting on her chest.Footnote 61 Theophilus Neil, whom we met in the previous chapter, allegedly explained a client's abdominal pains by stating that an ‘evil spirit [was] upon the sick man pressing him in his stomach’.Footnote 62 Isaac Niles diagnosed a client's problems as stemming from another family who had paid to put a spirit on him.Footnote 63 It seems likely that diagnoses of hostile spirit intervention underlay many or even all of the other cases as well. That it did not always appear in newspaper reports may derive as much from the fact that it was not an essential part of the means by which obeah was proved as it does from its conceptual absence.

The purpose of the ritual treatment offered by those accused of obeah was usually to catch, remove, or drive out the ghost, duppy, or spirit that was causing the problem. Healing techniques were directed to this end. Some healers literally aimed to catch the harmful ghost. Samuel Edwards caught a ghost with white calico and string, then tied it to an ackee tree.Footnote 64 George Williams likewise tied a duppy with a strip of white calico, having caught it underneath a bed.Footnote 65 Archibald Forbes buried nails under a tree at a cemetery and held a cutlass in his hand to kill a ‘bothersome spirit’, and later chased away another spirit from a house by throwing dirt and stones on it.Footnote 66 More often, healers used more indirect means of driving away the malevolent spirits, integrating elements found during the slavery era with new methods. The skills with which they did so were often very similar to those found by anthropologists who studied Caribbean healing techniques in the second half of the twentieth century.Footnote 67

Some specialists worked in graveyards to attempt to control the spirits of the dead. David Bates and Henrietta Harris, for instance, both conducted rituals at graves, in both cases pouring rum onto a grave, then flogging or switching it.Footnote 68 Others used bones or skulls, sometimes animal and sometimes human, to maintain a connection with the dead. Charles Dolly, a prominent ritual specialist who worked in Montserrat and whom we met briefly in the previous chapter, had a human skull which was ‘dressed’ with horse hair and a tin band wrapped around it.Footnote 69 The skull symbolized and instantiated the dead with whose spirits Dolly worked. Scrapings from bones were sometimes used as particularly ritually powerful substances. Dirt from graves was also powerful, used in combination with other materials and sprinkled in significant places to do ritual work.Footnote 70 Teeth were also often included in lists of objects taken from obeah defendants’ houses.Footnote 71 In both Trinidad and Jamaica the human body was an important source of ritually powerful objects.

Rum was another central component of the ritual complex, and was also intimately connected to the relationship with the dead just discussed. Almost every case that gives details of ritual material refers to rum. The spirit was used in all sorts of ways: it was mixed with powders, with rice and grave dirt, with cock's blood, or with scrapings from bone.Footnote 72 The resulting mixtures were sometimes drunk, and at other times used to anoint a sufferer's body in a ritual bath. Rum was rubbed into cuts, set on fire, or placed in a glass in the centre of a circle around which ritual activity took place.Footnote 73 Most frequently it was used as a libation – sprinkled on the ground inside or outside the house for the ancestors, the spirits of the dead. Rum featured in complex combinations of ritual substances. Alfonso McDermott, for instance, made a mixture of rum, corn, rice, and bone, then shook it together in a vial. After a further ritual involving spinning a pimento grain within a pipe shank, he threw some of the mixture outside.Footnote 74 The words that ritual specialists spoke while scattering rum, rice, blood, or a combination of these substances reveal that the purpose was often to provide sustenance for spirits with whom they worked. Stewart Carter took a drink of rum, then sprinkled the rest of it on the ground saying, ‘Take this and do the work.’Footnote 75 William Bruce similarly sprinkled rum on the ground, saying, ‘Come and take yours.’Footnote 76 John Daly threw rice outside his house, saying ‘Feed, good ones, and do my work,’ then a few minutes later threw more rice outside, along with rum, saying ‘Come forth at once, you are required.’Footnote 77 Carter, Bruce, and Daly directly addressed the spirits of the dead that they hoped would work for them. Rum was one of the most long-standing elements of Caribbean ritual practice; it had been mentioned in the 1760 Jamaican law that outlawed obeah. It drew on even longer traditions of sprinkling an alcoholic drink on the ground as a libation for spirits – a widespread practice in the African cultures from which some of the ancestors of the twentieth century had originated.Footnote 78

The other central element of the ritual complex found in obeah trials was the sacrifice of fowls, usually white. Like rum, fowls were mentioned in many cases. In one example, a group of ritual specialists had reportedly requested two fowls, one old and one young. One healer dug a hole while another severed the head of the young fowl with a cutlass, allowing the blood to trickle into the hole, then placing the head on top. The old fowl was then washed in a basin containing rum and placed under the floor of the house. Between them the two fowls were said to be guarding the yard, preventing anything dangerous from entering.Footnote 79 In other cases, fowls were cooked and eaten after sacrifice.Footnote 80

Along with sacrifices and libations, healing rituals frequently involved anointing, rubbing, or bathing the body of the person to be healed. Ritual specialists frequently prescribed healing baths, involving herbs and other materials boiled in water. The substances used in the bath might be gathered from growing plants, as in the case of Joanna Grant, who instructed her assistant to ‘go outside quickly and pick plenty bush, and boil a bath’, which she then used to bathe Rhoda Steel, who was sick because, Grant diagnosed, ‘Spirit is troubling her’.Footnote 81 Ritual baths sometimes also used the blood of sacrificed fowls, mixed with other material.Footnote 82 At least as commonly, however, material for ritual baths was purchased from shops. Henry Padmore, for instance, told Nathaniel Burke to ‘go to the apothecary and get 20 cents in musk, a phial of essence, 5 cents red lavender, and half-bottle of strong rum’. On Burke's return Padmore mixed these items together in order to give him a bath.Footnote 83 As one practitioner explained, such bathing or rubbing the body would ‘keep away ghosts’.Footnote 84

Ritual specialists did not just employ objects, but also had access to esoteric knowledge, both spoken and written. Many court reports described how spiritual workers spoke in an ‘unknown tongue’.Footnote 85 In Jamaica, evidence against those accused of obeah sometimes included the fact that they had made esoteric marks, often in chalk – signs that are common within the Revival and Spiritual Baptist traditions.Footnote 86 Jacob Hatfield, for instance, drew a chalk circle on the floor, with a cross inside it, on which he placed lighted candles and the money received from his client.Footnote 87 George Williams ‘traced quaint figures’ in chalk on a piece of board.Footnote 88 In Trinidad, however, making chalk marks was more likely to be included in evidence in cases brought under the Shouters’ Prohibition Ordinance.Footnote 89

Christian ritual, language, and iconography featured prominently in the activities that led to obeah prosecution, often integrated within other kinds of ritual practice. Most significant were the Psalms, which were frequently recited during ritual activity. Sheppard Moncrieffe, for instance, diagnosed that two duppies were causing an old man's illness. In his efforts to heal he asked the man's daughter to read a Psalm, then himself said the Lord's Prayer, spoke in an unknown tongue, and asked for a fowl and some rum for ritual use.Footnote 90 The Bible was also used, both to read from and as a ritual object. Rossabella Rennals passed a Bible over a pan of liquid, while George Forbes waved a Bible over his client's head while speaking in an unknown tongue.Footnote 91 Other practitioners put coins inside a Bible, or used it in divination rituals.Footnote 92 Elizabeth McPherson, for instance, used a Bible and some eggs to reveal the location of some stolen coffee.Footnote 93

Alongside rituals designed to remove ghosts, others focused on protection. Many practitioners provided ‘guards’ for their clients: assemblages of ritual substances, often tied in cloth, which were to be worn around the neck, kept in a pocket, or placed under a pillow.Footnote 94 Joseph Harvey, for instance, gave a client ‘what he called a guard’ to be worn around the waist, ‘made of a piece of new calico, in which was stitched a small bag containing a pebble, and threepence’.Footnote 95

Many of the materials and actions discussed so far feature prominently in other accounts of obeah practice.Footnote 96 The cases also reveal a ritual repertoire not always so visible in other sources. For instance, the cases reveal a significant role for eggs and eggshells in ritual practice. They were used in the preparation of ritual guards, as when Nathaniel Hall made a paste out of egg, vinegar, and powder, put it on a piece of flannel, and told his client to tie it to her stomach to protect her.Footnote 97 Eggs could also be used to influence: Walter Christian oversaw the burial of an egg, with rum and powder poured on top of it, outside his client's door, telling him not to remove it until after the court case whose outcome it was intended to affect had taken place.Footnote 98 The cases also demonstrate the importance of thread, often black, which was sometimes tied in knots while the names of people were called.Footnote 99 Beyond these regularly used materials, a huge range of other objects and substances played an occasional role in spiritual work. Prominent natural materials included garlic, lime juice, calabashes, asafoetida, lavender, pimento, and cedar wood or sawdust.Footnote 100 Ritual specialists also frequently made use of manufactured and purchased objects, especially mirrors, candles, marbles, and beads; and abrasive or pungent materials such as camphor, washing blue, brimstone, or carbolic balls.Footnote 101 A wide range of healing oils were also used. In a couple of cases these were manufactured oils labelled for specific occult purposes: Arthur Stone, arrested in Jamaica in 1922, had ‘oil of turn back’ and ‘oil of love’, while a later Jamaican defendant possessed oils including ‘oil of the rising man’, ‘oil of death’, and ‘oil of kill him’.Footnote 102 More common were oils with names denoting their ingredients rather than their function: variants on ‘oil of rignam’ were very common; also found were oils of cloves, of amber, of cinnamon, and of peppermint, along with products frequently sold as health-giving substances such as castor oil, camphorated oil, Epsom salts, and cod-liver oil.Footnote 103

The patterns in practices that led to prosecution for obeah drew on a repertoire of ritual practice that at its heart was about mediating between the living and the dead. The healing and cleansing rituals that led to obeah prosecutions were by no means all the same, but they drew on a shared pool of knowledge, although with geographical differences. The scattering of rum and rice, sacrifice of fowls and occasionally other animals, and use of human bones were all offerings to spirits, while other practices such as bathing and anointing with oils sought to alter a suffering person's relationship to the world of the spirits. Taken together, and even despite the hostile framework that generated the evidence, these similarities suggest deep underlying unities in what many of those prosecuted for obeah were doing, in their interpretations of problems, and their methods for addressing them.

The ritual practices revealed through these newspaper reports suggest strong resonances with African ways of interpreting and responding to harm and trouble. People prosecuted for obeah in the early twentieth-century Caribbean drew on a set of ideas and practices that had long histories and shared a great deal with other forms of New World African religious practice. That shared approach included openness to innovation and to incorporation of new elements and practices within an existing cosmological framework. The evidence thus speaks to some important questions in Caribbeanist historiography and anthropology, which has been preoccupied with the extent to which the Anglophone Caribbean societies did or did not maintain cultural practices derived from Africa, and whether they can be connected to specific African societies. At some important levels it does make sense to identify some of the ritual practices that were prosecuted as obeah as ‘African’, even while avoiding the pitfalls of tracing African ‘continuities’ identified by scholars such as Stephan Palmié.Footnote 104 Even so, in the early twentieth century, Anglo-Creole Caribbean ritual practice was primarily connected to Africa through parallels identified by observers, rather than through the direct consciousness of the practitioners. There is little evidence of connection to any specific region within the continent. Identification of certain phenomena as ‘African’, such as the actions of spirits in the lives of the living and the need to feed those spirits with rum and fowls, is the interpretation of the observer rather than of the practitioners. For early twentieth-century ritual specialists such ways of thinking and acting were part of a common-sense cosmology and embodied habitus which we can identify as incorporating African-derived elements, rather than an explicit orientation towards Africa. Spiritual workers today tend to be more consciously oriented towards Africa than were those practising in the early twentieth century. As the next section of this chapter will show, alongside important shared cosmological elements of obeah practice, there was also much diversity in the context in which ritual specialists practised their arts, within individual societies as well as between them.

The activities of those who appeared before the courts contravened the obeah laws in many ways. Some were religious healers who undertook healing work within a religious community or a balm yard. For instance Samuel Reid, also known as Doctor Reid, was involved with a Revival community in Clarendon. As part of his religious work Reid ‘kept a regular dispensary and hospital with a matron and other assistants’. He was first prosecuted for obeah in 1899. The evidence against him was that he had treated Sarah Fraser who, according to the Gleaner's reporter, had ‘got light-headed and half crazy from attending revival meetings’. Reid, in contrast to the Gleaner journalist, diagnosed that Fraser had three duppies inside her. She stayed at his hospital for three days, receiving treatment that involved taking ‘medicine’. In addition:

He…threw her on the ground and walked several times up and down on her body, to expel the ghosts. He also squeezed and kneaded her stomach with his hands for the same purposes. He then flogged her with a supple jack and afterwards his assistants or ‘soldiers’…formed a ring round Reid and all danced and shouted, and sang revival songs, Reid also sprinkled Mrs Fraser with…medicine, which he said would cut the duppies eyes ‘fine as linen’.Footnote 105

Reid's practice was thus a collective one, including many of the core elements established in the earlier part of the chapter as central to the practice of spiritual healing in the Caribbean – most fundamentally, techniques to rid his patient of the duppies that were causing her harm. Reid served at least some of his time in prison, but re-established his practice on his release. He was soon in court again, this time not for obeah but for practising medicine without a licence.Footnote 106 He was, according to the Gleaner, selling for ‘1s per bottle’ a cure-all ‘draught’ described as ‘a decoction of boiled weeds’, the recipe for which he had received by revelation and which was said to be popular with ‘great numbers of the peasantry of North-west Clarendon and the adjoining districts of Manchester’. Reid promptly paid his fine of £6 plus costs, but was convicted again for breach of the medical law in 1902.Footnote 107 The communal setting of Reid's practice distinguishes it from the stereotype of the isolated obeah practitioner, but was itself typical of a particular subset of religious healers whose work made them vulnerable to charges both of obeah and of practising medicine without a licence. This double illegality, however, also gave them some scope to use one law against another, in a form of plea bargaining.

We can see this plea bargaining in practice in two cases brought against the famous healer Rose Anne (Mammy) Forbes and her husband George, who together ran a popular balm yard (referred to in one newspaper article as a ‘Balming sanitorium’) at Blake's Pen, Clarendon, to which ‘people from far and near parishes suffering from various complaints travelled by the hundreds’.Footnote 108 The folklorist Martha Beckwith described Forbes, pictured in Figure 6.1, as ‘the most renowned’ of the balm healers in Jamaica.Footnote 109 Her balm yard operated under her daughter, Mother Rita, until well into the 1970s, and continues a more limited practice today.Footnote 110 Mammy Forbes pleaded guilty to a charge of practising medicine without a licence in 1910 and was warned by the magistrate to ‘destroy all her implements when she got home…for if the police found anything, such as bottles and feathers and took them to Court, a charge of obeah could be brought against her’.Footnote 111 While I have found no evidence that Mammy Forbes ever faced an obeah prosecution, her husband George was charged with obeah in 1916. At that trial, after hearing evidence about a ritual that involved words spoken in an unknown tongue, the words ‘praise father, praise son, and praise holy ghost’, a Bible, a basin of water, and the prescription of ‘balm’ liquid, the presiding magistrate ordered the charge reduced to one of practising medicine without a licence. The prosecuting policeman advocated imposing a fine that would be high enough to put the healers out of business. The £10 fine that Forbes actually received was clearly not enough to do this, although it may well have had serious economic effects.Footnote 112 In several other cases in the 1910s, prosecutions for obeah were effectively plea-bargained into charges of breach of the medical law. George Morgan, a St Lucian-born healer who worked in Jamaica and was also known as Clement Clarke, had a regular healing practice, indicated by a piece of paper found in his possession, stating: ‘Dr C. C. Clarke attends Mondays, Tuesdays and Saturdays.’ He was initially charged with obeah, but this charge was withdrawn when he agreed to plead guilty to a charge of practising medicine without a licence.Footnote 113 Sometimes it is hard to tell what, if anything, distinguishes such cases from those where obeah charges led to convictions, although the strong element of Christian worship must be part of what enabled George Forbes to avoid conviction for obeah.Footnote 114

Figure 6.1 ‘Mammy Forbes, the Healer’, photograph of Rose Anne (‘Mammy’) Forbes, from Martha Beckwith, Black Roadways: A Study of Jamaican Folk Life.

Further diversity of practice among Caribbean ritual healers is revealed in the widespread use of written and especially imported printed materials. A few of those arrested, including Popo Samuel, had books of handwritten notes and prayers. The police seized from Samuel ‘a copy book containing a number of prayers in which were the words “hallelujah…against my enemy, etc”’.Footnote 115 Printed books appeared more frequently than handwritten ones. Most often reported was the use of Bibles and prayer books, the contents of which were intimately familiar to most Caribbean people.Footnote 116 Ritual techniques often involved reading or reciting Psalms, both as something done by practitioners in the presence of clients and as a technique that ritual specialists instructed clients to undertake on their own at a later date.Footnote 117

Alongside Bibles, ritual specialists made use of occult and esoteric published works. As many studies have noted, spiritual practice in the Caribbean became intimately linked in the twentieth century to the publications of the DeLaurence publishing company in Chicago.Footnote 118 The newspaper evidence confirms this, and suggests the rapid circulation of DeLaurence books in the Caribbean after William DeLaurence published his first book in 1902. Evidence in the 1910 obeah trial of Dr Williams, of Siparia, Trinidad, included the fact that the defendant had a copy of a book described as ‘the Seventh Book of Moses’.Footnote 119 Versions of this book, more commonly named the Sixth and Seventh Book of Moses, appeared repeatedly in obeah trials.Footnote 120 The text, derived from medieval European grimoires, was brought by German migrants to the United States in the nineteenth century, translated into English, and published in various American editions, including most significantly by DeLaurence, Scott and Company in 1910. Dr Williams may have owned this, or perhaps another edition, possibly that published (also in Chicago) by Feliks Markiewicz.Footnote 121 In Jamaica, the earliest evidence of the circulation of DeLaurence publications that I have found is in the 1915 trial of Joseph Paddy of Smith's Village. Paddy had ‘several books’, including The Devil's Legacy and Mysteries of Magic as well as DeLaurence's Sixth and Seventh Book of Moses.Footnote 122The Devil's Legacy, which originated in America and was available at least from 1880, juxtaposes details of European witchcraft trials with quotes from Macbeth and instructions on how to ‘tincture silver into gold’.Footnote 123 A. E. Waite, the author/compiler of Mysteries of Magic, was a sceptical member of the Order of the Golden Dawn, a British occult organization founded in 1888. Mysteries of Magic was his 1886 translation and digest of work by the influential French occult writer Éliphas Lévi.Footnote 124

Among the many titles of esoteric books that appeared in obeah trials, the Sixth and Seventh Book of Moses and its variants were by far the most prominent. Also produced as evidence in several trials were two further DeLaurence publications, Egyptian Secrets and the Great Book of Magical Art.Footnote 125 The former was Egyptian Secrets of Albertus Magnus, another German-origin collection of folk medicine and spells, published in translation in the United States in the late nineteenth century and republished by DeLaurence.Footnote 126 The latter, appearing under a range of slightly different titles, were versions of DeLaurence's Great Book of Magical Art, Hindu Magic, and East Indian Occultism and Talismanic Magic, published under DeLaurence's name and consisting largely of a reworked version of Francis Barrett's The Magus, or Celestial Intelligencer (1801), itself compiled from earlier occult works.Footnote 127 By 1931 the Jamaica Gleaner was calling for action against the ‘numerous more or less ignorant persons [who] import from certain firms in the United States books dealing with such subjects as magical art (Hindu magic particularly), East Indian occultism, talismanic magic and other subjects very much akin to what is locally called the ritual of obeah’.Footnote 128 In 1940 the Jamaican Undesirable Publications Act made it illegal to import publications of the DeLaurence company, along with Communist literature and other literature deemed subversive.Footnote 129

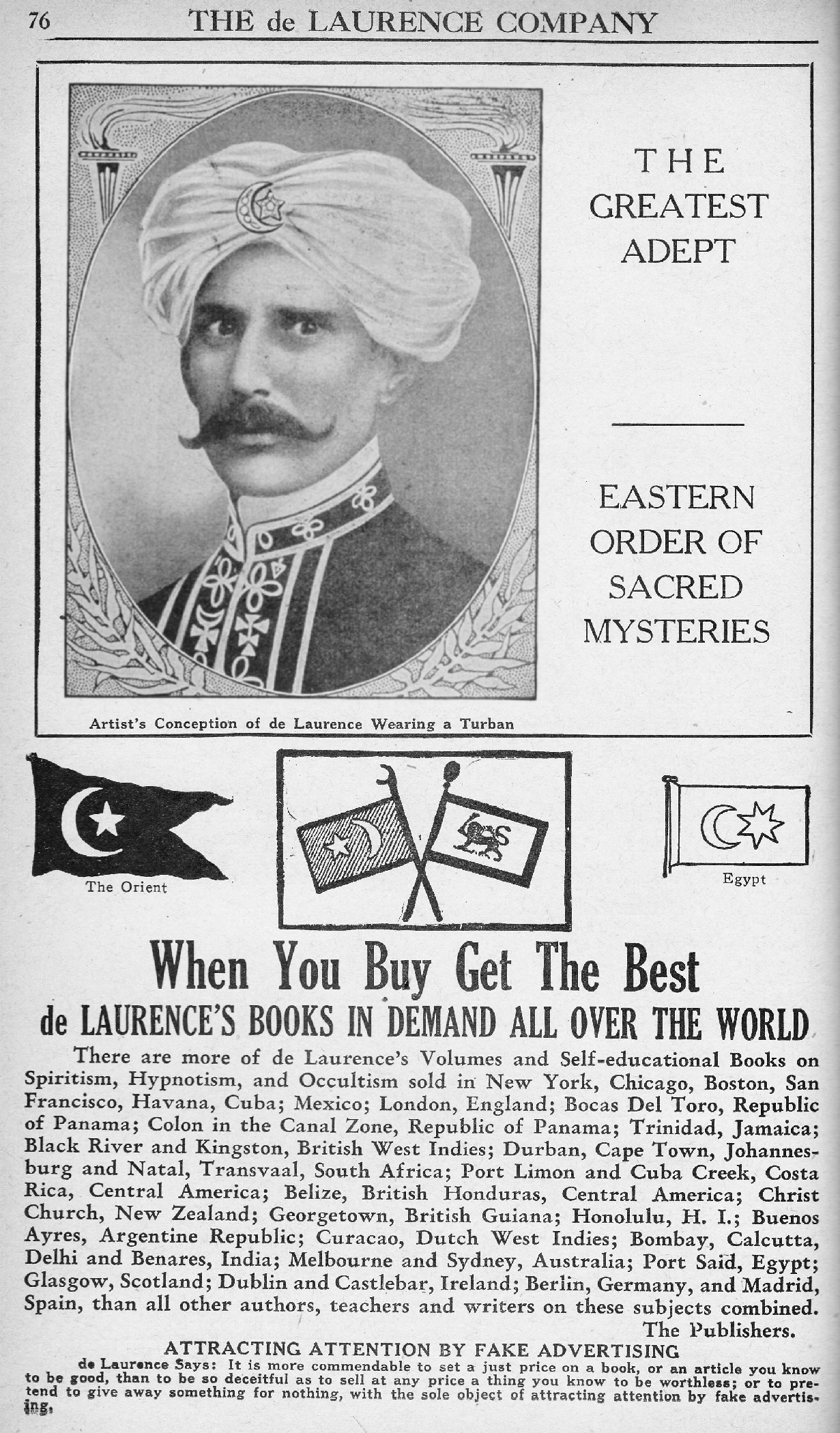

These books suggest the flexibility of Caribbean spiritual work and ritual practice. Although drawing on African interpretations of harm with spiritual causes, healers were clearly deeply attracted to what was presented to them as ‘East Indian’ or ‘Hindoo’ mysticism. DeLaurence, although an American of European ancestry, presented himself and his products as connected to India, using images of himself wearing a turban on his books and in catalogues and newspaper advertisements (for an example, see Figure 6.2).Footnote 130 He thus appealed to the orientalist fascination with ‘Eastern’ spiritual traditions common in late nineteenth-century Europe and America, expressed, for instance, in the appeal of theosophy.Footnote 131 Yet he seems quickly to have found that this form of marketing was also particularly appealing to African, African American, and Caribbean customers – including those who were themselves of Indian birth or descent.Footnote 132 People arrested in possession of the Great Book of Magical Arts included Gockool Maraj, who said he was a ‘Hindi priest’, and Beharry, who was described as ‘a middle aged East Indian man’.Footnote 133 The attraction of DeLaurence's works for those brought up as Hindus was perhaps as much in the unfamiliarity of what was presented within them as it was the books’ Indianness, for although they claimed connection with Hindu traditions, in practice their actual content was largely derived from older European works.

Figure 6.2 Advertisement from the DeLaurence company catalogue. Similar advertisements were published in Caribbean newspapers such as the Jamaican Gleaner.

The use of printed books was one of several methods by which Caribbean ritual workers integrated forms of knowledge from Europe and the United States into their practice. Additionally, many ritual specialists employed modern healing techniques that had not been integrated into biomedicine, such as magnetism, mesmerism, electrical healing, and hypnotism. Others drew on European methods of communication with the world of the dead, naming themselves faith healers and spiritualists. In some of these cases the police charged people with practising medicine without a licence rather than obeah. Professor E. J. Hall, who had worked in Jamaica and Trinidad before setting up a healing practice in Georgetown, Guyana, told the Demerara Chronicle that he ‘cured without drugs or surgery’ and specialised in ‘electro-therapeutics, radio-therapy, phototherapy, thermotherapy, hydrotherapy, diaduction, vibratology’.Footnote 134 In Jamaica, Professor Robert Bird Henderson used magnetism and massage in his healing practice. Both were charged with practising medicine without a licence.Footnote 135 Perhaps most prominent among this group was Alfred Mends of Kingston, who practised homeopathy and produced a certificate in court showing that he was licensed by the ‘Thompsonian College’ in the United States.Footnote 136 He was prosecuted on multiple occasions for practising medicine without a licence, and campaigned for changes to the medical laws that would enable homeopathic doctors to practise legally.Footnote 137 He would later become the editor of the nationalist journal Plain Talk, and a supporter of Marcus Garvey.Footnote 138

Others who did similar work used (relatively) new healing techniques including electrical healing in order to achieve goals such as removing afflictions caused by the spirits of the dead, thus becoming vulnerable to prosecution under the obeah laws. Professor Dawkins de Brown of Jamaica circulated printed advertisements for his electrical and herbal healing treatments, and also issued shares in his United Blue Ribbon Medical Electricity and Herbal Company. He was fined four times for practising medicine without a licence before receiving a twelve-month prison sentence in 1919 for practising obeah. The difference between the prosecutions for the two charges was that in 1919 a witness claimed that de Brown had ‘claimed to have power over evil spirits’, even while his main activity involved ‘electrical and herbal treatments’.Footnote 139 Another ‘Medical Electrical Specialist’, Simeon Luther Blagrove, was charged with both obeah and practising medicine without a licence, having received £10 from a man who wanted him to remove duppies. His practice included the use of an electrical machine that ‘pass[ed] healing power through the body’.Footnote 140

Even less apparently African than the mesmerists and hypnotists – and nevertheless still sometimes prosecuted – were people who combined work as ritual healers with performances designed to entertain. Travers Wright was arrested in Jamaica after he had advertised that he would ‘hold an entertainment to give an exhibition of his magic skill’. On arrest he said he was ‘a magician in the modern sense of the word and not an obeahman’.Footnote 141 Professor Joseph Maria Williams was prosecuted in Trinidad for practising medicine without a licence because he sold liquid medicine for an eye complaint; in his defence he argued that he was a conjuror who performed sleight-of-hand tricks, and had even performed before the governor of Jamaica and his wife.Footnote 142 Hubert Carrington likewise denied practising obeah, explaining that he used massage and electricity in his healing work and ‘used to give big performances on the stage and he never pretended to be able to work obeah’.Footnote 143

Other ritual specialists combined new European healing technologies with established African–Caribbean practices. As we saw in the last chapter, Arthur and Mary Clement described their work as mesmerism, but faced obeah charges for activities that included bush baths and the sacrifice of fowls. Beatrice Hanson described her work as spiritualism and said she had trained with Arthur Conan Doyle. Her ritual work included asking for ‘eye sight’ and speaking in an unknown tongue.Footnote 144 Such cases led to complex discussions in court that repeatedly circled around the need to distinguish between obeah and legitimate healing practices, while bemoaning the impossibility of doing so. The prosecution of Anita Smith and Charles Carter in Port of Spain is a particularly clear example. Smith and Carter were prosecuted after their entrapment by Detective Lambert, one of the several Trinidadian policemen who specialized in obeah cases.Footnote 145 Lambert organized a sting involving a man and a woman who posed as a couple claiming that the man had been having trouble in his job as an overseer on a sugar estate. According to the testimony of Margaret Thomas, who posed as the wife of the supposed overseer, Anita Smith went into a trance and told them that their problems were caused by ‘the bad spirit upon you’; they should ‘take a bath on the Third Stage of Science’. Thomas also reported that Smith stated that ‘it is not I speaking but the dead spirit in my body. I am now at the 12th stage of science and when I wake from here I will not know what I have said.’

In her trial, Anita Smith's defence was that Carter had induced her to act as a medium, hypnotizing her using techniques derived from Franz Mesmer. She did not know what took place while she was in a trance. Her defence lawyer read from the Encylopaedia Britannica's entry on hypnotism to prove that Smith's practice was not supernatural but rather was ‘genuine science’. In contrast, the prosecution argued that ‘the form of obeah in this case was that of mesmerism’. The trial was complicated by the fact that Charles Carter was a former police officer, that Margaret Thomas admitted to being Detective Lambert's lover and said she would do anything to help him, and that witnesses called Lambert's integrity into question in other ways, claiming for instance that he and others in the police regularly used mesmerism and hypnotism to work out whom to arrest in obeah and other cases. Rather than pitting rationality against superstition, as advocates of obeah law claimed it would, in this trial everyone involved was entangled in similar work in which multiple forms of magical and esoteric practices intertwined.

This case also reveals how the use of techniques such as mesmerism and hypnotism challenged the legal and discursive conception of obeah as an African phenomenon in the Caribbean. Few of the material objects removed from Smith and Carter's house were overtly connected to Africa. Nor, to the extent that there was any ritual described, did the ritual practice that they undertook seem particularly ‘African’. There was no animal sacrifice, no sprinkling of rice or libations of rum. There were candles involved but, the prosecution admitted, they were ‘ordinary ones with no obeahist marks upon them’, while a book and a letter taken had ‘nothing on them [that] showed they were obeahistic’. This left a leather-and-braid charm that was taken from Anita Smith. Cut open in court, the charm turned out to contain ‘some quicksilver and the bark of some tree’ as well as a handwritten copy of the twenty-third Psalm.Footnote 146 The magistrate was very interested in this charm, wondering if it was African or not. As he noted, ‘Obeah is supposed to go on in Africa and if this thing came from Africa it was possible that it had something to do with obeah.’ It turned out that the charm was indeed from Africa: a witness, Leopold Clarke, testified that he was a seaman and had acquired it in Durban, South Africa, from a ‘sweetheart’ there who gave it to him, telling him to ‘wear this and remember me’. He had brought the charm to Trinidad where he became Anita Smith's ‘sweetheart’, moved into her house, and passed it on to her. Asked whether the ‘charm’ was supposed to protect him, and whether he knew that ‘Africa is a great place for obeah’, Clarke reasonably replied that he didn't: ‘Africa is a big place,’ he said. The prosecution focused on the ‘charm’ in order to distinguish between obeah as something that is ‘supposed to go on in Africa’ and hypnotism as a European science. For the defendants, the charm may not have been particularly important, or it may have been one among several ritual objects. As a South African item, it had little to do with the ancestral West or West–Central African cultures that were said to underlie obeah. Yet from the court's point of view this was irrelevant; anything African was as good as anything else in proving both obeah and obeah's link to Africa. Although the legislation that prohibited obeah did not specify that it had to be African, the practical working out of the law in the courtroom meant that ‘magical’ practices that seemed to be connected to Africa were more easily prosecutable than those that appeared European.

The early twentieth-century Caribbean was the site of an intensely pluralistic healing arena, in which European biomedicine shaded into ‘alternative’ European-derived practices, which themselves overlapped with ‘traditional’ techniques derived from older European folk medicine, African means of healing, and skills imported by Indian migrants. Private healing sessions and collective religious rituals existed side by side with public performances that played with the uncertainty of illusions. Many individuals must have experienced or made use of multiple healing techniques and magical performances. Some descriptive terms, such as ‘mesmerism’, have clearly identifiable European origins, but it is in general neither possible nor analytically useful to attempt to clearly separate practices of European origin from those that are ‘traditionally’ African Caribbean or African, especially if the purpose of so doing is to suggest that the latter are more authentic than the former. Healers experimented with multiple traditions and techniques, as did those seeking treatment. Among the stories that emerged from obeah trials of people who sought relief from ritual specialists, we find many who had previously consulted biomedical and other kinds of practitioners. The laws about obeah, and most of the contemporary commentary on them, assumed that it was an African import or survival within the Caribbean region, and that its prosecution would enable the suppression of fraudulent African techniques of healing. In practice, it was difficult to distinguish obeah as African from other kinds of healing powers and practices that also, in a variety of senses, involved ritual, money, and objects. Meanwhile, the state and the medical profession were also involved in a battle to maintain boundaries between biomedicine and other forms of healing practice that were of low status, indeed that in Europe were often stigmatised. In the Caribbean, though, because of underlying anxiety about African culture, a claim that what one was doing was in fact mesmerism, electrical healing, homeopathy, or some kind of other unorthodox but not African-derived practice was a method by which people sought to distinguish what they did from the site of most intense stigma: obeah itself.