‘Arrest of an Alleged Obeah Woman’; ‘The Black Art. Jackson Pleads Guilty Quite Promptly’; ‘Alleged Larceny and Obeahism’.Footnote 1 These and similar headlines provided one means by which people in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Caribbean learned about obeah. Knowledge of obeah circulated in many other ways as well – written, oral, and experiential – but the printed medium of the newspaper played a particular role in the spread of information and understanding. Newspaper reports of obeah trials had a repetitive quality produced by the formulaic structure of the trial itself, moving through charge, evidence, verdict, and sentence, often packaged within an explicit message to readers provided by the magistrate judging the case, the journalist reporting on it, and sometimes both. The court rites of obeah trials, to adapt Mindie Lazarus-Black's phrase, led to the fashioning of a particular set of stories about obeah, constructed in relation to the needs of modern legal cultures to mark clear boundaries between the guilty and the not guilty, and to adjudicate the severity of offences through precisely calibrated punishments.Footnote 2 The definition of obeah in law from the second half of the nineteenth century onwards, and thus the requirements for a successful prosecution, led to trials that focused on three things: objects, ritual and money. Through direct spectatorship in court and newspaper reporting of trials, these elements over time acquired a larger status as the defining characteristics of obeah beyond the courtroom. They existed in tension with other aspects of Caribbean ritual practice that might in some circumstances be construed as obeah, but which rarely featured in court.

This chapter investigates obeah as a prosecuted crime from 1890 to 1939 in order to tease out the ingredients that made up official understandings of obeah in this period. It also examines the patterns that emerge from reports of obeah prosecutions to answer some empirical questions about them. How frequently were the obeah laws invoked? Who was likely to be prosecuted? How did people end up being charged with obeah? When people were prosecuted, were they generally convicted or acquitted, and if convicted, what punishments did they experience? How, if at all, were these patterns different in different places? To what extent did they change over time?

The chapter traces the stages of policing and prosecution of obeah, from the emergence of an individual as a suspect to their punishment or release. We can think of these proceedings as a set of journeys travelled by those known to be spiritually powerful or who were accused of practising obeah, journeys that might have a range of different outcomes, and might be repeated on several occasions over the course of a person's life. People arrested on suspicion of obeah might be prosecuted or released without prosecution; the charge they faced could change from obeah to one of several other crimes; they might, with or without the help of a lawyer, offer a range of arguments in their defence, or plead guilty and offer no defence at all. They might be convicted or found not guilty, if found guilty might appeal, and could experience a range of sentences. What emerges through this analysis is that, despite the official rhetoric that surrounded the obeah law, which emphasized that it was intended to suppress belief in obeah and thus to produce a more ‘civilized’ population, in everyday use the laws regulating obeah had no such impact. Prosecutions might be used to bolster police reputations, to attack religious leaders, to pursue conflicts between individuals and groups within local communities, or in response to relationships between ritual specialist and client that had for some reason gone awry. That is, prosecutions were part of a world in which ritual healing practices were ordinary.

People were prosecuted for obeah in every British colony in the Caribbean. Rather than trying to track cases across the entire region, this chapter focuses on Trinidad and Jamaica, while occasionally supplementing evidence about them with material from other colonies.Footnote 3 Along with the next chapter, it is based on a large body of material about obeah prosecutions, collected through a systematic search of the dominant newspaper in Jamaica and Trinidad in the period 1890–1939. I begin in 1890 for two reasons. The first is analytic: my initial research on the development of the law and of politics strongly suggested an upsurge in concern about obeah after this date, with laws passed in many colonies in the 1890s and 1900s. There is also a pragmatic reason: newspapers from before 1890 are less systematically available, and, where digital editions have been produced, the optical character recognition of newspaper text printed prior to 1890 is poor, making searches unreliable. The initial systematic research was on Jamaica, again for a mix of analytic and pragmatic reasons: it was the first place that criminalized obeah; concern about obeah was particularly intense there; and the law against obeah was particularly harsh, and perceived as such. Pragmatically, the existence of a digitized edition of the main newspaper, the Gleaner, made it possible to locate cases relatively quickly. With the help of research assistants I was able to collect newspaper reports on obeah cases from 1890 to 1989.Footnote 4 We searched the digital edition of the Jamaica Daily Gleaner and Sunday Gleaner, using the keywords ‘obeah’, ‘obeahman’, ‘obeahwoman’ and ‘obeahism’, and also looked for cases of practising medicine without a licence that were connected to obeah. I also investigated obeah cases from Trinidad, chosen because it was another large jurisdiction within the Caribbean, but one with a history that in many ways contrasts with that of Jamaica. Trinidad was a late addition to Britain's Caribbean empire, with a very culturally mixed elite and a large East Indian population. For Trinidad, court cases were collected from the microfilmed Port of Spain Gazette.Footnote 5 As this process was much more time consuming than searching the Gleaner, and it was not possible to search until 1989, I limited the period searched to 1890 to 1939 as the likely peak period for prosecutions, because the search of the Gleaner had revealed a significant decline in prosecutions after 1939. Investigating two colonies in this way avoids the problems of assuming that a single territory stands for the entire Caribbean, while providing a larger and more systematic body of evidence than can be obtained by selecting examples from across the region. Trinidad and Jamaica were both large colonies within the British Caribbean context, with contrasting histories. These differing histories meant that – to emphasize only the most obvious difference between them – by the turn of the twentieth century there was a significant Indian-origin population in Trinidad but only a small one in Jamaica, a result of the importance of indentured labour in post-emancipation Trinidad. The two colonies also exemplify the two main types of obeah law that existed across the region: Jamaica had specific ‘Obeah Acts’, revised on multiple occasions in the 1890s and early 1900s, while in Trinidad obeah was illegal under the ‘Summary Conviction Ordinance’, a composite statute that defined and specified punishments for many minor offences.

In addition to collecting arrests and prosecutions for practising obeah, we collected reports about related offences. In Jamaica, but not Trinidad, a significant group of people was charged with consulting an obeah practitioner, and some were charged under vagrancy laws with being persons ‘pretending to deal in obeah’. A few individuals in each colony were prosecuted for possession of ‘materials to be used in the practice of obeah’ or ‘instruments of obeah’.Footnote 6 We also included cases where obeah was explicitly considered as a potential charge, but where the defendant was ultimately charged with another crime: larceny or practising medicine without a licence.

Both the Gleaner and the Port of Spain Gazette filled considerable space with reports of the proceedings of magistrates’ courts. The papers did not, however, claim to be comprehensive; undoubtedly there were trials for obeah that they never reported. Sometimes cases trail off frustratingly, with reports that a verdict or sentence will be delivered the next day, but no follow-up story. In addition, we will certainly have missed some cases due to flaws in the optical-character-recognition digitizing process and through oversights when scanning the microfilm editions. Thus although I present figures for the prevalence of different trial outcomes and punishments, and the different characteristics of defendants by gender and ethnicity, these should be taken as broad rather than precise indicators. Nevertheless, these chapters are certainly based on the largest compilation of obeah cases any researcher has so far collected. This material allows us to raise and begin to answer some questions that would otherwise be impossible to consider.

The mass of evidence acquired from the newspapers demonstrates that obeah was a contested category. There are recognizable patterns in the actions, objects, and words that were presented as evidence that someone was practising obeah, and these fed into the reproduction of the stereotype of the obeah man. But these patterns do not exhaust what can be gleaned from the evidence. A tremendous range of practices and of contexts came before the courts. The evidence also hints at the existence of other activities, popularly known as obeah, that were never or very rarely prosecuted because they did not fit obeah's legal definition. This large body of evidence also allows for comparison and for the evaluation of similarity and difference over time and across space. It reveals important similarities between Trinidad and Jamaica, but also some significant differences. It shows Jamaica to have been a colony with a harsher judicial system than Trinidad, at least with regard to obeah. Obeah was prosecuted more regularly there, those prosecuted for it were found guilty more frequently, and those found guilty were punished more severely. Obeah acquired a particularly powerful symbolic and political role in Jamaica as the activity that in the early twentieth century represented the population's backwardness, a cultural weight that was spread more diffusely among a range of cultural objects and practices in Trinidad.

Jamaica and Trinidad, like other British colonies, shared with the metropolis a common-law tradition characterized by a nested hierarchy of courts, an adversarial system of prosecution, and a judicial process that took place in public. Cases were brought by a prosecuting lawyer or police officer acting on behalf of ‘the Crown’, a legal fiction that implied the representation of collective interest in the prosecution of criminals. Those prosecuted, known as defendants, had the right to be represented by lawyers, if they could pay for them. In both colonies obeah cases were tried at the lowest level of the criminal justice system, in courts known as police courts, petty sessions courts, or resident magistrates’ courts. These courts were presided over by magistrates most of whom had no legal training and were part of the local elite. In the capital cities of Kingston and Port of Spain the magistrate's court was known as the police court, met every day, and was overseen by paid magistrates; in the rural areas the resident magistrates’ courts (in Jamaica) and petty sessions courts (in Trinidad) met every few weeks in a local town and were overseen by an unpaid magistrate. The magistrate decided on verdicts and sentences without the aid of a jury. Except when their decisions were appealed, records of the business of these courts were not formally archived. As a result, in most cases the reports of their proceedings that appeared in newspapers provide the only evidence available about the proceedings of these courts. In total, we recorded 813 reports of arrests and prosecutions for obeah-related crimes in Jamaica and 121 for Trinidad (see Table 5.1).Footnote 7

Table 5.1 Arrests and prosecutions for obeah and related offences, reported in the Daily Gleaner and Port of Spain Gazette, 1890–1939

| Jamaica | Trinidad | |

|---|---|---|

| Practising obeah | 625 | 91 |

| Practising obeah and additional charge | 29 | 3 |

| Consulting an obeah man/woman | 50 | 0 |

| Vagrancy (obeah related) | 38 | 0 |

| Larceny (obeah related) | 24 | 9 |

| Possession of obeah materials | 21 | 1 |

| Obtaining money by false pretences (obeah related) | 9 | 12 |

| Practising medicine without a licence (obeah related) | 17 | 0 |

| Aiding and abetting the practice of obeah | 0 | 5 |

| Total | 813 | 121 |

The choice to charge someone with obeah was one of several possibilities open to police who made arrests. The elements that made up the crime could also, if put together in other ways, contribute towards prosecutions for other offences, some of them more serious than obeah. Most significant was larceny, which regularly led to multiple years’ imprisonment, compared to obeah's maximum penalty of a year's imprisonment and a flogging.Footnote 8 Larceny charges were usually brought in relatively unusual situations that did not involve entrapment and where the parties did not know each other in advance. The clients involved in cases that led to larceny charges had generally been coerced or tricked into passing over money, rather than doing so in the context of a ritual. Other charges that frequently overlapped with prosecutions for obeah involved less serious charges, including practising medicine without a licence, obtaining money by false pretences, pretending to tell fortunes, and, in Jamaica but not Trinidad, vagrancy. Practising medicine without a licence overlapped with obeah but could only be punished with a fine, not a prison sentence or a flogging. Some of those prosecuted for it were not doing anything that could be interpreted as obeah, but many were offering ritual and spiritual healing services that shared a good deal with some of the activities that were prosecuted as obeah.

The most striking finding is the much larger number of cases reported for Jamaica than for Trinidad. One would expect to find more Jamaican than Trinidadian cases, since the Jamaican population was more than twice the size of that of Trinidad and Tobago, and the Port of Spain Gazette rarely reported the proceedings of Tobagonian courts.Footnote 9 But even taking this into account, as well as the possibility that some of the difference is due to the Gleaner's greater resources or its greater interest in reporting obeah cases, it is clear that obeah was more vigorously pursued in Jamaica than in Trinidad. In addition to the larger number of prosecutions in Jamaica, this chapter will show that those prosecuted were more likely to be found guilty, and that those found guilty received harsher sentences. Jamaican authorities were also more concerned to promulgate new obeah laws, and paid more attention to obeah as a problem.

One reason for the greater intensity of prosecutions in Jamaica was the existence in Trinidad for the second half of this period of the Shouters’ Prohibition Ordinance, which, as discussed in Chapter 4, made it illegal after 1917 to participate in the services of the Spiritual Baptist faith. No such law ever existed in Jamaica. We found twenty-nine prosecutions brought under the Shouters’ Prohibition Ordinance between 1917 and 1939. Spiritual Baptists sometimes appeared in court on their own or in groups of one or two, but frequently in groups of 16, 20, 26, or even 130 defendants.Footnote 10 Altogether at least 500 people were prosecuted under the Ordinance, many more than under the obeah and related laws.Footnote 11 In court, hundreds of co-religionists appeared to support their brethren and sistren: 200 attended a hearing in Chaguanas in 1918.Footnote 12 As the next chapter demonstrates, in Jamaica people involved in Revival religion, which played a similar cultural role in Jamaica to that of the Spiritual Baptist faith in Trinidad, were regularly prosecuted for obeah. In contrast I found almost no evidence of people affiliated with Spiritual Baptist communities being prosecuted for obeah in Trinidad.Footnote 13 The absence of an equivalent law in Jamaica making Revival illegal – despite the efforts of some individuals to pass one – meant that the circumstances in which obeah laws, along with some other laws such as the Night Noises Law and laws against breach of the peace, were used in Jamaica were different from their application in Trinidad.

The availability of the Shouters’ Prohibition Ordinance does not fully account for the difference between Jamaica and Trinidad, however. Jamaica's much longer history of official preoccupation with obeah also played a significant role. In addition, as I will show, the significant East Indian population of Trinidad seem to have been less likely to experience prosecutions for obeah than people of African descent, whereas in Jamaica Indians were more likely, in relation to their proportion of the population, to be prosecuted for obeah than African Jamaicans.Footnote 14 The fact that obeah prosecutions were, in the ethnically divided society of Trinidad, more likely to be used against African Trinidadians may be another reason for the greater intensity of Jamaican obeah prosecutions.

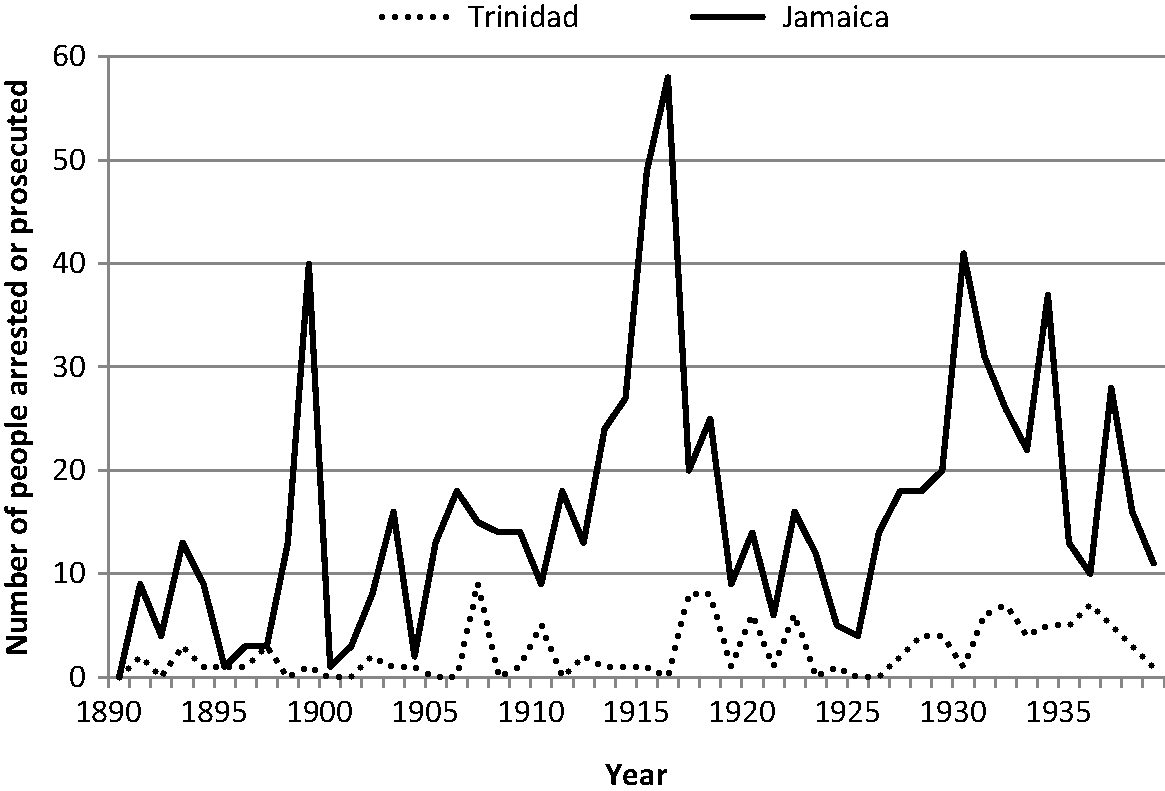

In both Jamaica and Trinidad the number of cases brought fluctuated considerably over time (see Figure 5.1). Fluctuations could result from policy decisions within the higher ranks of the police force, sometimes prompted by press and political agitation for a campaign against obeah. In Jamaica there was a clear peak in 1898 and 1899, a result of determined efforts to enforce the newly passed 1898 Obeah Act. In the wake of its passage, the Clarendon police went on a ‘vigorous crusade’ against obeah practitioners, resulting in thirteen convictions in that parish in the first year of the new law's existence.Footnote 15 Similarly, in the year following the passage of the 1904 Leeward Islands Obeah Act, significant numbers were convicted of obeah in some of the territories it covered, most notably Nevis, where thirteen were convicted within a year.Footnote 16 Anti-obeah campaigns could also take place without a change of the law. In 1916, the year of the largest peak in obeah prosecutions, two policemen in Manchester, Jamaica, were assigned specifically to prosecute obeah practitioners, leading to reported arrests of one group of seven people and one of five.Footnote 17 Jamaican prosecutions then fell back for most of the 1920s before rising to sustained higher levels during the 1930s. Convictions and gendered patterns of arrest followed the same pattern as overall prosecutions, as did the pattern for the various specific crimes. In Trinidad, with fewer cases altogether, the pattern is even more jagged. There too, there were sometimes police campaigns against obeah. In 1933 the Port of Spain Gazette reported that a Tobago policeman ‘has been digging out the seers of the Island’.Footnote 18 In some years we found no obeah cases at all. The peak year for cases was 1907, a year which saw a single case in which five people were charged with obeah.

Figure 5.1 Arrests or prosecutions for obeah and related offences in Jamaica and Trinidad, 1890–1939.

Who was prosecuted for obeah? As Table 5.2 shows, in both colonies, but especially in Jamaica, defendants in obeah cases were predominantly male, as had also been true during the period of slavery. The charges of practising medicine without a licence and of consulting an obeah practitioner (only found in Jamaica) were somewhat more evenly distributed by gender, although still dominated by men, while larceny charges were with only two exceptions brought against men.Footnote 19 These patterns reflect patterns both of prosecution and of practices of spiritual healing.

Table 5.2 Gender of defendants in obeah and related cases (percentages are of those of known gender)

| Jamaica | Trinidad | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Unknown | Men | Women | ||

| Practising obeah | 552 (90%) | 61 | 12 | 68 (75%) | 23 | |

| Practising obeah and additional charge | 20 (69%) | 9 | 0 | 3 (100%) | 0 | |

| Consulting an obeah man/woman | 30 (60%) | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vagrancy (obeah related) | 31 (82%) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Larceny (obeah related) | 22 (92%) | 2 | 0 | 9 (100%) | 0 | |

| Possession of obeah materials | 19 (90%) | 2 | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 | |

| Obtaining money by false pretences (obeah related) | 7 (78%) | 2 | 0 | 11 (91%) | 1 | |

| Practising medicine without a licence (obeah related) | 13 (76%) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Aiding and abetting the practice of obeah | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (20%) | 4 | |

| All cases | 694 (87%) | 107 | 12 | 93 (77%) | 28 | |

| Total | 813 | 121 | ||||

Women's spiritual healing practices were less likely than men's to be construed as obeah and thus to be prosecuted, because they tended to take place in collective settings. When women were prosecuted for obeah, they were much more likely than men to be arrested for actions undertaken within a religious community. Ellen Barnes, for instance, was found guilty of obeah after she was entrapped by a man who claimed to be ill but was in fact a policeman in disguise. Her premises in the parish of Hanover, Jamaica, were marked by a flag on a 48-foot pole; she carried a Bible, candle, and whip. Barnes led the assembled members of her church in worship that involved drumming, singing, prayer, and the reading of chapters from the Bible before attempting to heal the policeman, whom she said had three spirits on him. Her activities were recognizably related to Revival religion and her healing, which involved further reading of Bible verses and the provision of medicinal liquids, was a part of the Revival tradition.Footnote 20

Defendants came from predominantly poor and working-class communities. They reported that they made their living through a range of almost entirely working-class occupations such as labourer, bricklayer, poultry-rearer, gardener, higgler, washerwoman, or cultivator. The prosecution of an occasional middle-class person for obeah was surprising enough to attract crowds, extensive comment from journalists, and sometimes special treatment from the magistrate. The Gleaner described the prosecution of David Bates, a schoolmaster and inspector for the poor, as ‘sensational’, noting the ‘very great interest throughout the parish on account of the position once occupied by the accused’, while the prosecution of Victoria Doyle, former schoolmistress in Guapo, southern Trinidad, attracted a large crowd of spectators to the courtroom.Footnote 21 Defendants lived in both urban and rural settings; many had lived overseas or had been born outside Jamaica or Trinidad.

Representations of obeah continued to tie it tightly to Africa throughout this period, although defendants in obeah cases were by this time very rarely African born. I found only five cases in the 1890–1939 evidence that described obeah defendants as African: two in Jamaica and three in Trinidad.Footnote 22 Nor was prosecution for obeah limited to people of African descent, although they were the majority in both colonies. People of Indian birth or descent also appeared in court for obeah-related crimes, although I found no reports of people identified as white being prosecuted for obeah.Footnote 23

Prosecutions for obeah played a distinctive but different role in constructing race in the two colonies. In Trinidad, East Indians were significantly underrepresented among those prosecuted for obeah, in relation to their share of the population. Sixteen of the 121 obeah defendants (13 per cent) were described as East Indian or ‘coolie’, in a colony in which people of Indian origin made up just over a third of the population.Footnote 24 It seems that, in a colony where division between people of African and Indian descent was a crucial element of colonial control, prosecution for obeah was part of what marked out African Trinidadians as a distinct group. Also markedly disproportionate to their share of the population, but in the other direction, was the prosecution of Indians for obeah in Jamaica. There, where blackness was much more of an assumed norm and people of Indian origin never exceeded 2 per cent of the population, people identified as ‘East Indian’ or ‘coolie’ made up 4 per cent of those prosecuted for obeah (thirty-five individuals). This was a small proportion of the total, but at least twice what would be expected if the prosecutions took place without regard to ethnicity.Footnote 25 In Jamaica, then, Indians had come to be understood as particularly likely to practise spiritual work, while at the same time their small numbers meant that Indian spiritual traditions were assimilated to ‘obeah’. If Jamaicans sought out people of Indian origin as spiritual workers, believing them to have access to particularly strong spiritual power, this was interpreted by all concerned as the Indians practising obeah. A Gleaner article published in 1890 hinted at this, reporting that ‘our people say “the Coolies are the best obeahmen”’.Footnote 26 In contrast, in Trinidad, although East Indians were sometimes understood to be obeah men, their spiritual practice was also understood as taking place within Hindu or Muslim ritual contexts, and thus as something other than obeah – Kali Mai Puja, for instance.Footnote 27 People of Indian origin certainly undertook rituals that involved the use of spiritual power to heal, but these were relatively infrequently labelled ‘obeah’ and were less likely to lead to arrest, although not guaranteed to be allowed to take place freely.Footnote 28 In the end, though, all this may simplify the complex understanding of race and ethnicity at work in both Trinidad and Jamaica. In Trinidad a man who called himself Baboo Khandas Sadoo was charged with practising obeah in 1919. Described as a man ‘of the bold negro type’ and as being ‘of African descent’, he had converted to Hinduism and spoke ‘Hindustani’, and had an altar with ‘figures of Hindoo gods and devils’.Footnote 29 His case suggests the complex movement that could take place across apparently stable categories.

In both colonies, about two-thirds of those arrested for obeah-related offences were prosecuted as individuals, with most of the rest taken to court in pairs (see Table 5.3). A few in each colony were brought to trial in larger groups of up to seven defendants. In some of these group cases one individual was prosecuted for obeah and several others for consulting an obeah man.Footnote 30 Women were significantly more likely than men to be prosecuted in groups of two or more people, suggesting again that they tended to be prosecuted for obeah for activities undertaken in the context of collective religious practice.Footnote 31

Table 5.3 Numbers of defendants in obeah and related cases (number of cases is stated first, followed by number of defendants in parentheses)

| Jamaica | Trinidad | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 539 (539) | 88 (88) |

| 2 | 85 (170) | 9 (18) |

| 3 | 18 (54) | 3 (9) |

| 4 | 4 (16) | 0 |

| 5 | 5 (20) | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 (6) |

| 7 | 2 (14) | 0 |

| Total | 653 (813) | 101 (121) |

People tried for obeah were very likely to be convicted. In Jamaica 81 per cent of those charged with obeah-related offences, where the outcome is known, were convicted. In Trinidad convictions were slightly less likely, but at 78 per cent still represented a very high proportion of prosecutions.Footnote 32 As Table 5.4 shows, at least in Jamaica, those charged with practising obeah itself were more likely to be convicted than were people charged with most other obeah-related offences. The main exceptions were the cases of practising medicine without a licence, for which there were fourteen convictions and no reported acquittals. This outcome probably results from the fact that these cases often represented a kind of plea bargain, in which someone initially charged with obeah agreed to plead guilty to unlicensed medical practice in order to get a lower punishment.Footnote 33 These rates of conviction echo high conviction rates for prosecutions heard in lower courts across the common-law world.Footnote 34 They significantly exceed the conviction rates for obeah charges brought during slavery, when, as shown in Chapter 3, between 40 and 56 per cent of defendants were convicted. Thus, the transition from a regime where obeah was a very serious crime to one where it was a minor offence meant expanded scope for prosecutions and a greater likelihood of conviction for those prosecuted.

Table 5.4 Outcomes of obeah cases (percentages are of known outcomes)

| Jamaica | Trinidad | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guilty | Acquitted | Unknown | Guilty | Acquitted | Unknown | |

| Practising obeaha | 391 (84%) | 73 | 160 | 59 (79%) | 15 | 17 |

| Practising obeah and additional charge | 14 (78%) | 4 | 11 | 1 (33%) | 2 | 0 |

| Consulting an obeah man/woman | 25 (58%) | 18 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vagrancy (obeah related) | 17 (81%) | 4 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Larceny (obeah related) | 12 (63%) | 7 | 5 | 5 (63%) | 3 | 1 |

| Possession of obeah materials | 7 (50%) | 7 | 7 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Obtaining money by false pretences | 4 (50%) | 4 | 1 | 8 (89%) | 1 | 3 |

| Practising medicine without a licence (obeah related) | 14 (100%) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aiding and abetting the practice of obeah | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (75%) | 1 | 1 |

| Subtotal | 484 (81%) | 117 | 211 | 77 (78%) | 22 | 22 |

| Total | 812 | 121 | ||||

a One Jamaican case in which the defendant died before trial is excluded. Therefore the total number of Jamaican cases in this table is 812, rather than the 813 in Table 5.1.

People convicted of obeah might receive a fine or a prison sentence; the prison sentence could be accompanied by flogging if the defendant was male.Footnote 35 The maximum allowable sentence for practising obeah in Jamaica was until 1898 twelve months’ imprisonment and up to seventy-five lashes; the 1898 Obeah Act maintained the maximum prison sentence but reduced the maximum number of lashes to eighteen. Maximum punishments in Trinidad were lower: six months’ imprisonment and corporal punishment (no maximum number of lashes was specified in the legislation, but the most I found in practice was twelve).Footnote 36 Other crimes were subject to different punishments: obeah-related vagrancy and possession of obeah materials could be punished with fines or imprisonment, while those convicted of practising medicine without a licence could not receive a prison sentence, only a fine. People convicted for larceny could not be flogged, but could receive long prison sentences, of up to eight years.

Overall, Jamaican magistrates, as well as being more likely to convict, tended to impose more severe punishments. This is not surprising since the maximum allowable punishments under the obeah laws were harsher there. Nevertheless, as Table 5.5 shows, Jamaican magistrates reached for the heavier end of the spectrum of permitted punishments more frequently than did those in Trinidad. When the law gave them the choice they were more likely to send people to prison, more likely to add a flogging to a prison sentence, and less likely to use fines.Footnote 37 Prison sentences in Jamaica were also considerably longer than in Trinidad, reflecting the maximum allowable prison sentence of twelve and six months, respectively: the median term of imprisonment for obeah was six months in Jamaica and four months in Trinidad, while the most frequent prison sentence in Jamaica was twelve months, compared to six months in Trinidad (the maximum allowable sentence in each case).Footnote 38 As well as ordering longer prison sentences, Jamaican magistrates also allotted more lashes. In Trinidad, the six sentences of flogging were for twelve lashes on four occasions and six on one (on one occasion the number of lashes was not reported); in Jamaica the median number of lashes was also twelve, but the most commonly awarded number of lashes was eighteen.Footnote 39 Sentences of eighteen lashes or more were passed in Jamaica on thirty-five occasions, and in five cases the maximum sentence allowed by the 1898 Obeah Law of eighteen lashes was exceeded.Footnote 40

Table 5.5 Punishments of those found guilty in obeah and related cases (percentages are of known outcomes)

| Jamaica | Trinidad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine | Imprisonment | Imprisonment and flogging | None | Unknown | Fine | Imprisonment | Imprisonment and flogging | |

| Practising obeah | 36 (10%) | 248 (67%) | 83 (22%) | 4 (1%) | 20 | 23 (39%) | 31 (53%) | 5 (8%) |

| Practising obeah and additional charge | 2 (15%) | 10 (77%) | 1 (8%) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

| Consulting an obeah man/woman | 14 (58%) | 8 (33%) | 2 (8%) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vagrancy (obeah related) | 3 (18%) | 14 (82%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Larceny (obeah related) | 0 | 12 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (100%) | 0 |

| Possession of obeah materials | 0 | 6 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 |

| Obtaining money by false pretences | 0 | 4 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (100%) | 0 |

| Practising medicine without a licence (obeah related) | 14 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aiding and abetting the practice of obeah | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%) | 2 (67%) | 0 |

| Subtotal | 69 (15%) | 302 (66%) | 86 (19%) | 4 (1%) | 23 | 24 (31%) | 47 (61%) | 6 (8%) |

| Total | 484 | 77 | ||||||

People who were acquitted usually disappeared from written sources, although some later reappeared as defendants, and occasionally as witnesses. Those convicted were taken to serve their prison sentences or to pay their fines. Some of them contested their convictions through appeals, which were decided in courts overseen by professional judges, either in Kingston or Port of Spain. The judges did not hear witnesses, but discussed the evidence that had been presented in the light of arguments from defence lawyers that the magistrates’ decisions had been faulty. Table 5.7 shows appeals, representing 14 per cent of both Jamaican and Trinidadian cases that resulted in conviction. Appeal cases are probably overrepresented, because cases in the appeal court were more likely to have been reported in the newspapers than those that did not result in appeal. This is confirmed by the fact that in several of the appeals we found no report of the earlier conviction. Nevertheless, even if an overestimate, this still suggests a considerable effort made to appeal against convictions for obeah-related crimes. Despite their regularity, appeals were unlikely to succeed. Less than a third of Jamaican appeals were successful, while in Trinidad we did not find a single successful appeal.Footnote 41

Table 5.6 Extent of prison sentences in obeah-related cases, in months (percentages are of known outcomes)

| Jamaica | Trinidad | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤3 | 4–6 | 7–9 | 10–12 | >12 | unknown | ≤3 | 4–6 | >12a | |

| Practising obeah | 63 | 103 | 26 | 135 | 0 | 4 | 17 | 19 | 0 |

| Practising obeah and additional charge | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Consulting an obeah man/woman | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vagrancy (obeah related) | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Larceny (obeah related) | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Possession of obeah materials | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Obtaining money by false pretences | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| Aiding and abetting the practice of obeah | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Subtotal | 88 | 114 | 31 | 145 | 6 | 4 | 21 | 30 | 2 |

| Total | 388 | 53 | |||||||

a There were no sentences of more than six months and less than three years’ imprisonment.

Table 5.7 Appeals against obeah and related convictions

| Jamaica | Trinidad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of appeals | Conviction upheld | Sentence reduced | Conviction overturned | Unknown outcome | Number of appeals | Conviction upheld | Unknown outcome | |

| Practising obeah | 55 | 28 | 5 | 17a | 5 | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| Practising obeah and additional charge | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Consulting an obeah man/ woman | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vagrancy (obeah related) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Larceny (obeah related) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Possession of obeah materials | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Obtaining money by false pretences | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Practising medicine without a licence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aiding and abetting the practice of obeah | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 66 | 34 | 6 | 21 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 4 |

a Includes one case where the initial appeal was unsuccessful, but the defendant was later granted a ‘free pardon’ by the governor. ‘Woman Convicted under Obeah Law is Granted Pardon’, Gleaner, 10 March 1924.

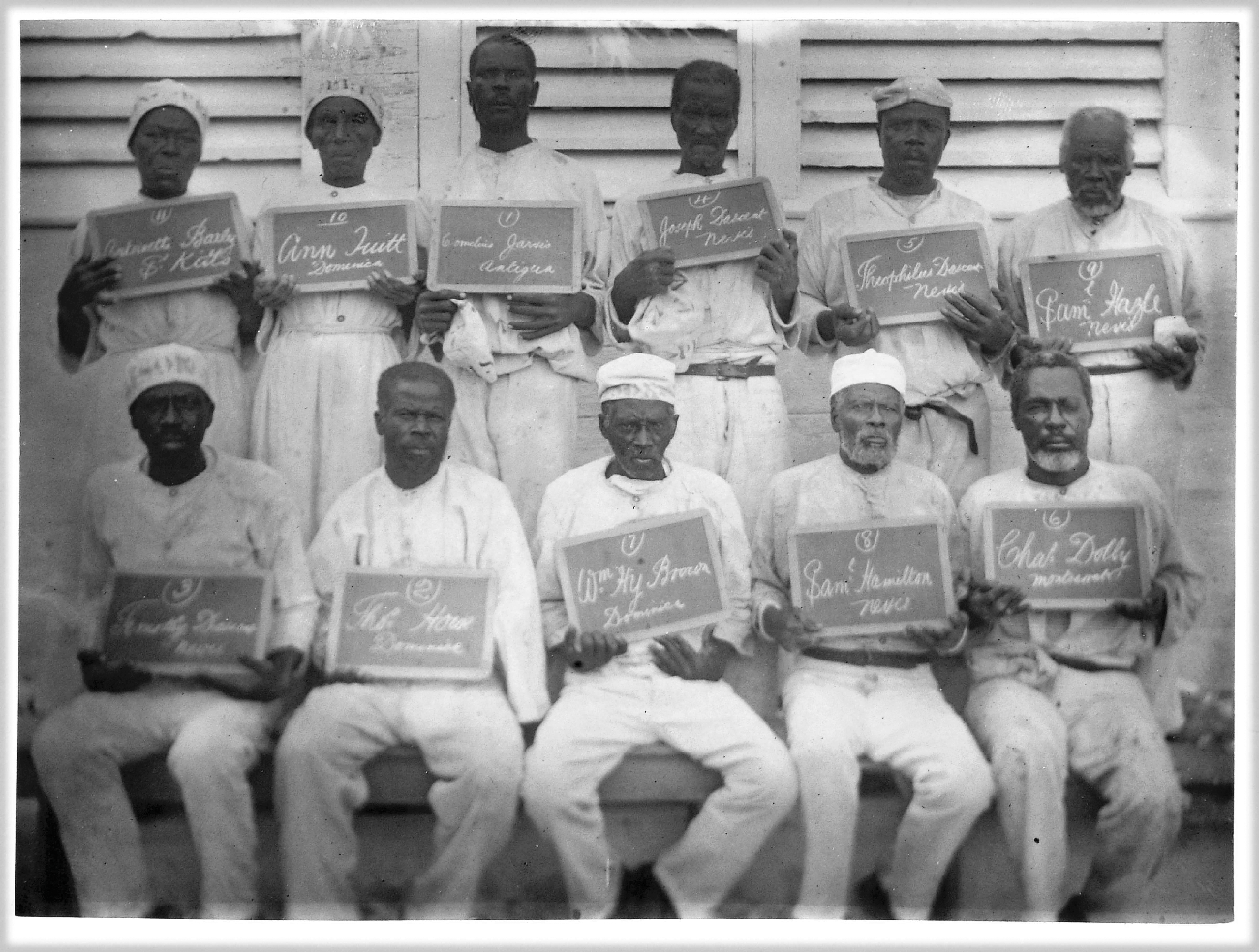

How did these prosecutions for obeah and related crimes work? How did people come to be prosecuted, and what did prosecution mean to defendants, their families, and to people around them? The crime of obeah existed as one element in a larger culture in which concern about spiritual danger was all around. In this context a reputation as an obeah man or obeah woman was a double-edged sword. On one hand, some people prosecuted for obeah presented themselves in court with a sense of pride in ritual practice or spiritual power. In one of his several trials in Montserrat for obeah, Charles Dolly (pictured in Figure 5.2) explained that a board with a piece of glass attached was a tool for divination (‘for the purpose of showing him what had happened’), and offered to ‘give a demonstration of his skill in Court’ before prophesying that an accident would befall ‘some members of the Commissioner's family’. He also said ‘that the police knew nothing of obeah’ but were ‘aware of his skill’.Footnote 42 On the other hand, for many the allegation of obeah use was a serious slur worth fighting, not least because it suggested that their achievements or status were not authentically gained. When Amelia Baker of Trinidad responded to a policeman's caution by telling him that he had ‘got his stripes by the aid of obeah’, this was a serious insult; he responded by arresting her and charging her with using ‘violent language’.Footnote 43

Figure 5.2 Charles Dolly, front row, far right, pictured in 1905 in the Antigua gaol as one of a group of convicts serving prison sentences for obeah.

The negative popular perception of obeah as something dangerous and malicious is visible in the considerable number of slander cases, especially in the Jamaican courts, in which allegedly defamatory words included accusations that an individual had used obeah.Footnote 44 These suits were brought despite the fact that in bringing them plaintiffs risked drawing attention to the very accusation that they rejected.Footnote 45 Ellen Knight won damages from another woman she accused of saying that she ‘was holding the communion cup in the one hand and obeah in the other’ and also that Knight had worked obeah and killed her accuser's mother.Footnote 46 Two years later another slander suit turned on the allegation that a man consulted an obeah man ‘to work obeah’ against two rival businessmen, and ‘that he had a croaking lizard in his store licking his goods to give him luck’.Footnote 47 Slander cases reveal both that people accused each other of obeah use, meaning it in wholeheartedly negative terms, and that those so accused felt themselves to be seriously wronged. The slur that someone used obeah threatened their efforts to become a respectable person, distanced from poor and working-class behaviour and cultural practices. Popular understandings of obeah were complex: it inspired fear and anxiety when people suspected that it had been used against them, and it was something that most did not want to be associated with. At the same time, it was a form of power that many hoped to be able to access for themselves.

Slander cases invariably focused on accusations that obeah had been used to harm, and, in particular, as in two of the three cases quoted above, to kill. Suing for slander was no doubt an unusual reaction to accusations that one had hurt someone with obeah. Another response, also occasionally made visible through newspaper accounts of court proceedings, was to more directly attack the person making the accusation. Charles Moore, for instance, was prosecuted for beating a woman who claimed that he practised obeah.Footnote 48 In another case two men appeared in court for wounding each other in a fight which followed an attempt by one of them to ‘advise’ the other ‘to stop the practising of obeah and ganga [sic] smoking’.Footnote 49 People also sometimes physically attacked those they thought had used obeah against them. In Trinidad, James Scipio attacked another man with his cutlass, declaring as he did so that ‘it is you who work obeah on me and prevent me from getting work’.Footnote 50 These cases allow a glimpse into what we might call a common or reputational knowledge about obeah practice. They emphasize that although the laws against obeah were created by elites who hoped to use them to demonstrate the colonies’ modernity and to control popular religion, they were also sustained from below. Prosecutions for obeah existed within a broader framework in which obeah was widely considered dangerous, even while some of the practices prosecuted as obeah were part of everyday life.

In some senses then, the obeah laws simply reinforced popular hostility to dangerous obeah practice. Yet not all actions popularly considered to involve elements of obeah were vulnerable to prosecution. Obeah was defined in Jamaican law as the act of ‘any person who, to effect any fraudulent or unlawful purpose, or for gain, or for the purpose of frightening any person, uses, or pretends to use any occult means, or pretends to possess any supernatural power or knowledge’. In Trinidadian law it was ‘every pretended assumption of supernatural power or knowledge whatever, for fraudulent or illicit purposes, or for gain, or for the injury of any person’.Footnote 51 In both societies, as well as in other colonies, the crime of obeah had two elements: the pretence to ‘supernatural power or knowledge’; and the fact that this was done for gain, fraud, or to hurt someone. In practice, obeah cases almost always focused on the ‘gain’ rather than on the other purposes listed in the laws, and thus required the prosecution to demonstrate that money or, very occasionally, goods, had been exchanged for ritual services. Spiritual work that did not involve these elements was not vulnerable to prosecution as obeah. People who undertook ritual activity on their own behalf or on behalf of a friend or neighbour without any obvious payment or intended harm were not in law practising obeah, although what they did might well be popularly understood as obeah. In Port of Spain, a woman serving as a witness in a court case was arrested for ‘strewing coarse salt on the staircase’ of the court, which everyone involved interpreted as an attempt to use supernatural means to influence the trial's outcome. Rather than facing prosecution for obeah, she was charged with ‘indecent behaviour’.Footnote 52 Popular and commercial culture was full of depictions of women using obeah to ‘tie’ their lovers, often by placing ritual objects including menstrual fluid or vaginal secretions in their food.Footnote 53 Prosecutions for obeah did sometimes revolve around relationships, especially men's desire to use spiritual power to force or persuade women who had left them to return. But they included very few prosecutions in which women were alleged to have ‘tied’ men. One of the few such cases that we found was a 1902 Trinidadian desertion suit, in which Mrs Humphrey sued her husband for leaving her three years previously to live with another woman. Mr Humphrey's defence was that his wife had practised obeah on him by placing a collection of crushed bone, grave dirt, and his nails and skin under his pillow. Her anger when he confronted her over this was what led him to leave, he claimed. It does not seem to have occurred to Mr Humphrey that he might try to prosecute his wife for obeah, and indeed a case brought on the basis of such evidence might well have failed. Mrs Humphrey's activity was understood by everyone in the court as a form of obeah practice, yet was not legally defined as such.Footnote 54 Another took place in Jamaica in 1913 when Cecelia Daley and Frank Campbell were charged with vagrancy for actions that, the Gleaner reported, ‘amount to obeah’ – but, it seems, were not quite legally considered to be so. The two had provided a woman with ritual material designed to increase her husband's love for her.Footnote 55 The rareness of such cases may be because ‘tying’ took place much less frequently than the fears expressed in calypsos and stories suggest, but probably also results from the fact that it could be done privately by women without the involvement of a paid ritual specialist. Similarly, obeah prosecutions very rarely heard evidence about the placing of protective ‘obeah bottles’ in trees and around houses, despite the frequent depiction of this as an obeah activity in works of fiction, folklore, and travel writing (see Figure 5.3).Footnote 56 Prosecutions for obeah, then, intersected only partially with the activities that were popularly deemed to constitute obeah. Yet because the legal definition of obeah made the paid encounter between ritual specialist and client a defining characteristic of the crime, such encounters became an important model for obeah practice.

Figure 5.3 ‘Obeah’ in Jamaica, The Graphic, 2 July 1898, p. 22. This illustration to an article about Jamaica in the context of the Spanish–Cuban–American war shows the ubiquity of obeah as a symbol of the Caribbean more generally. The obeah bottle was part of standard representation of obeah, but is rarely found in obeah prosecutions.

In order to show how the legal definition of obeah affected broader understandings, much of the rest of this chapter traces the experience of being prosecuted for obeah, from arrest to conviction. It examines two cases at length, one Trinidadian and one Jamaican, while drawing on other material to show alternative outcomes or trajectories. The first case I attend to is the prosecution in 1910 of Mary Clement and her husband Arthur, of Woodbrook in Port of Spain. The second involved Theophilus Neil of the rural community of Princess Hill, near Linstead in central Jamaica, in 1924. These prosecutions were not typical, but they are particularly telling and were reported in detail. The two cases also exemplify the two main modes by which obeah prosecutions came about: through civilian reports to the police, on the one hand, and through entrapment by police or their agents, on the other.

The story of how someone might end up in court for obeah could be narrated with many starting points, but the evidence available to the historian dependent on newspaper reports usually begins at or shortly before the individual's arrest. Let us start, then, with the earliest information we have about Mary and Arthur Clement and Theophilus Neil. In the Trinidadians’ case, a woman named Annie Stewart, who described herself as a Wesleyan, testified that in May 1910 she and her husband had visited the Clements, seeking relief from Mr Stewart's serious illness. A friend had advised them of the Clements’ healing abilities. Arthur Clement diagnosed Mr Stewart as having ‘devil spirits’ on him that were causing his ill health, and treated him by sacrificing a fowl, placing its blood on a plate between his legs, reciting prayers, and burning a ‘filthy scented liquid’ mixed with rum. He then instructed Mr Stewart on how to take a daily herbal bath for the next six days. Mr Stewart's health did not improve, and not long afterwards he died. On 22 June, a month after the Stewarts had visited the Clements, Corporal Joseph Alexander went to search the healers’ house under warrant for ‘articles used in the practice of obeah’. Alexander, also known as Cola or Kola, became notorious in early twentieth-century Trinidad for his police work, including several prominent arrests for obeah.Footnote 57 He did not explain in court why he sought the warrant, but Annie Stewart's evidence suggests that he did so because she went to the police in the aftermath of her husband's death. Stewart stated in court that she had never believed in the Clements’ power, but had visited them with her husband in order to ‘please’ him.Footnote 58 The prosecution of the Clements was thus initiated by a civilian, in this case because of Annie Stewart's disappointment at the failure of their healing and her distress at her husband's death.

Cases like this, initiated by a member of the public reporting someone to the police in the hope of instigating a prosecution for obeah, accounted for more than half of Jamaican cases, and around a third of Trinidadian.Footnote 59 In Annie Stewart's case it is relatively clear why she went to the police. Even so, she might have responded in many other ways to her husband's death; why she chose this course of action over others is less easy to judge. In this and in many similar cases it is hard to get much insight into the motivations of those who reported people to the police for practising obeah, because the discourse of newspaper reporting and of the courtroom relied on two fictions: first, that any citizen would report any breach of the law to the police; and second, that the illegal act of ‘practising obeah’ was clearly distinguishable from other similar, but legal, acts. As a result, in many cases the motivations of the person who went to the police with information about an alleged obeah practitioner were actively excluded from reports and testimony. For instance, according to the Gleaner a man named Thomas told a policeman that he had been approached by Thomas Mortimer Hood. Hood told him that he ‘had seen a ghost on his wife’ and could remove it through spiritual means. Thomas later accompanied two policemen to Hood's house in order to trap him into contravening the obeah law.Footnote 60 We do not know why Thomas initially went along with Hood's suggestions and then later reported him. Nor did the magistrate who heard Hood's case raise the question. Thomas could have simply ignored Hood, or refused his offers of help. Why did he, instead, go to the trouble of reporting the situation? Such questions are in many cases unanswerable. They remind us of the limitations of the knowledge that we can achieve through written records about the encounters that led to obeah prosecutions.

As the cases of the Clements and of Thomas Hood show, people who offered ritual or spiritual services risked arrest, especially when, like Thomas Hood, they actively sought out people to treat. Yet the risk must have been relatively low. Incidents in which people went to the police must have been strongly outnumbered by those in which the practitioner succeeded in recruiting a client, or else these approaches would not have continued.

In some cases, often those in which a defendant employed a solicitor to argue his or her case in court, testimony or contextual information reveals something of the reason why the person who eventually became a witness went to the police. In many of these incidents, testimony suggests a breakdown in the client's confidence in the spiritual worker. This might be, as in the case of Annie Stewart and her husband, because the spiritual work failed.Footnote 61 Or it could be because the client concluded that the work was excessively costly, as in a case when a man named Moody consulted Charles Johnson in the hope of getting a job. He and his friend later reported Johnson to the police because (according to Johnson's lawyer) ‘they thought the amount charged was too much and they doubted the man's powers’.Footnote 62 In other cases the ritual specialist failed to return to complete the work promised, despite accepting money, and as a result the client eventually reported him. Letitia Gilbert, for instance, initially accepted William Francis's offer to remove the duppy that he said was causing her long-term sickness. Francis began a ritual, sprinkling white rum in her room, and then left, promising to return the next day. He did not come back. Gilbert took no further action until, after more than two months, she encountered Francis by chance, at which point she reported him to nearby police, who arrested him.Footnote 63 In this case it seems that Gilbert initially trusted Francis's powers, but felt cheated by his failure to return.

The involvement of the police in cases like these seems to have been a last resort, a back-up technique when informal efforts to resolve conflict had failed. Letitia Gilbert would not have reported William Francis if he had returned the next day, as he had promised. In a similar case, Eliza Walker consulted Isabella Francis after two biomedical doctors were unable to help her sick daughter. Francis gave her ‘two bottles of some liquid and a little bag for the child to wear to keep off the evil spirit which was on the child’. After several weeks during which her daughter's health did not improve, Walker returned to Francis, asking for the return of the bangles that she said she had given in payment. Only when Francis refused to return the bangles did Walker go to the police.Footnote 64 In these cases police enforcement of the obeah laws resembled not so much an effort to eradicate obeah as a kind of regulatory procedure through which unsatisfied clients could deal with unscrupulous or incompetent practitioners. Despite official rhetoric about the usefulness of prosecution in ridding Jamaica or Trinidad of obeah and belief in obeah, in practice obeah cases often worked in response to the demand of clients for whom obeah was most definitely real.

On other occasions the police were, apparently willingly, drawn into disputes in working-class communities. Those who persuaded the police to prosecute someone for obeah could damage their rivals or enemies. Thus, for instance, Eliza Barnett was prosecuted, her defence lawyer claimed, because she refused to lend money to a neighbour, Boaz Bryan. Angry at being turned down, Bryan worked with the local policeman, Constable Lewis, to trap Barnett into committing ritual acts to remove hostile spiritual power. The trap led to Barnett receiving a six-month sentence for obeah.Footnote 65 In a similar case, Emanuel Faulkner and John Barnes were charged with possessing ‘implements of obeah’. Under cross-examination two key witnesses who had provided information to the police leading to the raid on Faulkner and Barnes's yard revealed that they were former tenants of Faulkner with whom he had frequently ‘quarrelled’, and that they had left owing him rent.Footnote 66 In such cases, the person who went to the police had known the person reported for some time, and could have reported him or her earlier, but chose to do so at this particular moment because of the developing conflict between them.

In contrast to these cases initiated by civilians, the majority of cases in Trinidad, and a large minority of those in Jamaica, resulted from a policeman's decision to attempt to arrest a ritual specialist. The other case that I will trace in detail provides a good example of this situation, which often involved extended effort to entrap the suspect. Theophilus Neil's arrest in 1924 followed a decision by Detective Euriel Augustus Watson of the Linstead police in Jamaica to pursue him.Footnote 67 Detective Watson learned of Neil's reputation as an obeah man while investigating the murder of Leah Malcolm, for which Neil's cousin Christopher Fletcher was eventually convicted. Neil's brother George, also a spiritual healer, became an accessory to the murder because he helped Fletcher dispose of the body, although he emphasized that his work was not about killing or harm: ‘It is not me who kill the woman. I don't work that sort of obeah. The sort of obeah that I work is to drive away spirits and to cure sickness.’Footnote 68 In the course of a lengthy investigation, Watson must have come to see Theophilus Neil as a possible target for prosecution as well, although there were no claims that he had anything to do with Malcom's death. Watson persuaded David Rennals to visit Theophilus Neil at his home in Princess Hill with the deliberate intention of acquiring evidence that he had broken the obeah law. Rennals was not a policeman, but acted on the promise that he would receive a reward if Neil was convicted. He went to Neil's place along with a friend, James Morgan, and claimed that he needed to get treatment for a sick man for whom he was responsible. Neil, although initially reluctant, eventually agreed to advise him. Asking first for 10 guineas, Neil accepted 25 shillings from Rennals, which Rennals paid in notes that Watson had marked for later identification. Neil then worked to ‘dismiss’ a ghost which he said was ‘squeezing the sick man in his stomach’. After working with a pack of cards and three dice which he placed on a mirror, Neil gave Rennals three bottles of liquid and explained how he should use them to treat the sick man, who should also be anointed with a few drops of the blood of a fowl, mixed with the liquid provided. Rennals returned to the police station and gave the bottles of medicinal liquid and other material to Watson, who then went with a warrant for Neil's arrest under both the Obeah Law and the Medical Law.

Police-led arrests sometimes took the form of raids on the premises of suspected obeah practitioners, or opportunistic arrests of people with a reputation while they were going about their business. More commonly, as in Neil's case, they were achieved through subterfuges, sometimes elaborate, designed to entrap ritual specialists into committing illegal acts. The people employed to act as decoys in these cases were more frequently women, and they often appeared in multiple cases and collaborated closely with the police.

The arrest of Theophilus Neil shares many features with other entrapment cases, including the use of pairs of policemen or police spies so as to have corroborating witnesses, deployment of marked money, and the production of convincing narratives by plain-clothes police or civilians acting on behalf of the police. Entrapment narratives often involved ill health, but also revolved around employment, the success of businesses, court cases, and other matters. Either the police or their agents participated in the ritual activity, then revealed their identity and arrested the practitioner.

What led the police to pursue particular individuals at particular moments? As explained above, Neil came to Watson's attention because of his brother George's conviction as accessory to murder in a prominent trial. In other cases the police had apparently wanted to prosecute particular individuals for a long time, but had not been able to do so because of the suspects’ knowledge of police techniques and ability to protect themselves against them. When Jasper Roberts was prosecuted for practising obeah, a newspaper reported that the police had been watching him for ‘some three years’, but ‘all attempts to get at him had proved futile’. They were finally able to entrap him when two men who had sought his help in a court case in which they were defendants described his practice to the police after their conviction. Two constables then posed as the relatives of the convicted men and went to ask why they had not succeeded in getting off. (Roberts said it was because they had not consulted him early enough.) The constables then asked for spiritual help with their own (invented) problems, in order to be able to testify to his ‘pretending to supernatural power’. Even then, Roberts was extremely cautious. He made the two constables take an oath before he would discuss anything of substance with them, then refused to take payment for his work because his ‘concubine’ said that ‘the detective had been seen down the road that morning’. When they returned to try to pay the following week, Roberts refused to have anything to do with them. He was nevertheless arrested, convicted, and sentenced to a year's imprisonment and ten lashes.Footnote 69

Roberts's caution was commonplace among successful ritual specialists, who knew how the police operated and took precautions to defend themselves against arrest. Like Roberts's ‘concubine’, their friends and kin warned them against potential police surveillance. While police were hiding in the hope of arresting a man in Diego Martin on the outskirts of Port of Spain, a ‘little girl’ called out a warning: ‘Don't work tonight because the police hiding in the cocoa.’Footnote 70 Ritual specialists took note of other signs that a trap was being set. Joseph Reid, confronted with a putative client claiming to be in need of spiritual treatment for poor health, recognized that the man was a police constable and chased him away with a cowskin whip.Footnote 71 Suspect Joseph Donald refused to continue a ritual when his client produced the money provided to her by the police, saying that ‘he could not work because the money had marks on them’.Footnote 72 Theophilus Neil had been suspicious of David Rennals when he arrived asking for help, initially deflecting him by asking whether there were not people who could help him closer to where he lived, and why he had not sought help from a biomedical doctor, before eventually agreeing to treat him. Ritual specialists operated with an awareness of the illegality of their practice and considerable knowledge of police tactics. It is therefore likely that on many occasions they were able to prevent police from collecting sufficient evidence to enable them to prosecute. Indeed, the police regularly complained of their difficulty in arresting obeah suspects. A policeman giving evidence at the trial of Joseph Paddy of Smith Village in 1915 testified that ‘we used to hear a lot about him but we couldn't catch him’, while a press report about an arrest the previous year noted that ‘the police in their many attempts at bringing [George Black] to book were always beaten’.Footnote 73

The police involved in obeah arrests were often stimulated by personal ambition, since successfully prosecuting obeah practitioners was a means to professional advancement. They were also at times motivated by personal grudges or hostilities against those they prosecuted. Such grudges, although usually concealed in the sources, occasionally emerge, as for example in another case brought by Joseph Alexander (Kola) a few years before he arrested the Clements. In 1907 he arrested Leopoldine Moise at her house a few blocks from Port of Spain's central Woodford Square. Moise's defence lawyer argued that the arrest, through entrapment, was a ‘filthy conspiracy’ brought as a result of Kola's ‘individual grudge’ against his client, which arose because Moise had provided ritual services to Kola's former partner Natalie Contreville. Kola believed that Moise had supported Natalie in her court case against him for breaking into her house, and had harmed his new partner through spiritual work. Contreville testified that on leaving the courthouse after her successful case against him, Kola said to her that ‘the Guadalupe woman’ – meaning Moise – ‘made you bring this case’. Moreover, Moise claimed that, when he entered her house to arrest her, Alexander stated, in Trinidadian Creole: ‘I am Cola Alexander. You have made Natalie win her case over me before the Magistrate, and to-day you have fallen into my hands.’Footnote 74 The statement suggests something of Kola's pride in his reputation, as well as his personal motivations. Despite the compromised motivations of a major witness, Moise was found guilty and her later appeal was unsuccessful: according to the appeal court judges it was ‘obvious’ that Moise had been practising obeah.Footnote 75 This case gives a sense of how far the reality of obeah prosecutions might differ from the idealized legal process in which prosecution for obeah served to break down popular belief in its power. Kola seems to have been as convinced as anyone of Moise's ability to use spiritual power to help Natalie; indeed, it was the fact that she had done so that motivated him to bring the prosecution.

Entrapment, though ubiquitous, could be controversial. Charles Frederick Lumb, an English-born judge who practised in Trinidad and Jamaica between 1887 and 1909, opposed its use in obeah cases, declaring it ‘loathsome and unEnglish’.Footnote 76 A Colonial Office official agreed, describing the use of ‘agents provacateurs’ as ‘discreditable’, while the Port of Spain Gazette questioned the ethics of cases in which ‘the principal witness for the police [might be] a bare-faced and hardened perjurer’.Footnote 77 Nevertheless, the practice of entrapment continued throughout the period, in both Trinidad and Jamaica. The Colonial Office refused to endorse Lumb's critique, approving the use of entrapment while noting that it should be used ‘as little as possible’.Footnote 78 The Chief Justice of Trinidad also approved of entrapment.Footnote 79 The Colonial Office's directive that entrapment should be used sparingly hardly restrained police practice, since in any individual case it could be argued that it had been necessary to gain a conviction. It became a standard part of police procedure, featuring, for instance, in material such as the Trinidad Constabulary Manual, which noted: ‘It is almost always necessary to employ “Police Spies” in order to detect & prosecute to conviction persons charged with the practices of Obeah.’Footnote 80

In entrapment cases there was usually a moment when the subterfuge was revealed: at a certain point within a ritual the policeman stopped posing as a client seeking spiritual help, declared his real identity, and physically took hold of the ritual specialist, announcing his or her arrest. This was a dramatic point of crisis and transition, when the police revealed themselves and thus asserted – or attempted to assert – the superior power of the state over that of the ritual specialist and his or her spiritual power. In cases where the police had been posing as the client of the obeah practitioner, there were usually additional police officers hiding outside the house in which the ritual was being undertaken, who rushed into the room and grabbed the accused when a previously agreed signal – a cough or some specific words – was given. Theophilus Neil's arrest departed from this pattern in taking place at a later date, when the people arrested were surprised by police with warrants.

The process of arrest was usually presented in court as smooth and straightforward, despite evidence that it was frequently violent or at least confrontational, often attracting considerable attention. Joseph Paddy's arrest in Smith's Village created a ‘furore’.Footnote 81 Those arrested and their families and neighbours sometimes tried to fight off arrest, or to dispose of objects that they feared would be used as evidence against them. Mary Clement ran to the back of her yard when the police arrived, apparently trying to hide. When Theophilus Neil was arrested his family, according to Detective Watson, tried to ‘make away with things’, and he threw away a thread bag, later produced in court, which contained a phial of liquid, a set of human teeth, some coins, a mirror, a smaller bag, and a stone. Others protested their innocence, giving explanations about why what they were doing did not constitute obeah. Victoria Doyle told the arresting officer that ‘she didn't work obeah but only makes prayers’, having previously told her putative client that ‘I do things to make a case drop but I don't work obeah’.Footnote 82 Arthur Stewart in Jamaica protested on his arrest, ‘Me not working obeah. Me only burning candles.’Footnote 83 These efforts to discriminate between practising obeah and other kinds of spiritual work would later be echoed in court.

After making an obeah arrest, the police usually searched the suspects, their homes, and their possessions, often seizing large quantities of material. When Matthew Russell Gordon was arrested in Spanish Town three men were hired to carry his possessions from his home to the police station, where they ‘filled the entrance room’. Anything that might remotely be connected to obeah was taken. In Gordon's case, this included ‘human skulls, jaw bones, charms, bundles of bush, vials of evil-looking and evil-smelling liquids’ – all items from the ‘traditional’ repertoire of obeah practice – but also a ledger, a bank book, cash, and foreign bank notes.Footnote 84 Joseph ‘Kola’ Alexander stated that he searched the Clements’ premises and found a series of rather ordinary objects which he nonetheless described as evidence of obeah: ‘a vessel with oil into it and a wick burning…two demijohns containing a liquid that to him tasted like sea water [and] a saucepan with something that smelt like rum’. Detective Watson searched Theophilus Neil's house in Neil's presence, and found a selection of objects, all of which might have multiple uses, but which Watson and the court interpreted as evidence of obeah practice: mirrors, phials, nails, bottles containing liquids, human hair, letters addressed to Neil, books, and two lamps. All were seized and later presented in court as evidence against him. These searches and seizures were driven by the law, which in Jamaica explicitly stated that someone found in possession of ‘instruments of obeah’ could be assumed to be an obeah practitioner, unless evidence to the contrary could be presented. Instruments of obeah were very broadly defined, as ‘any thing used, or intended to be used by a person, and pretended by such person to be possessed of any occult or supernatural power’.Footnote 85 In Trinidad the law was not explicit on this point, but nevertheless the display of objects in court was an important part of the practice of obeah prosecutions. Objects seized by police could eventually find their way into works of anthropology and folklore.Footnote 86

Some of those arrested for obeah were no doubt released without being charged, and certainly without being brought to trial. Many press reports of arrests where no follow-up trial was reported may well have ended in this way. But in many cases the suspected obeah practitioner was formally charged and taken for trial at the magistrates’ court, police court, or petty sessions court. Theophilus Neil was arrested on Sunday 2 November, held in the Linstead lock-up for a few days, and brought to the Linstead resident magistrates’ court the following Wednesday for a brief hearing which simply stated the bare facts of the prosecution's case. He was then remanded in custody back to the lock-up before his full trial, which took place over two days the next week. The Clements’ full trial also began ten days after their initial arrest. Others might await trial for considerably longer. Leopoldine Moise, for instance, was arrested on 1 November 1907 and brought before the Port of Spain city police court the next day, but her full trial did not take place until the following January.

There were minor differences between the two colonies in the charges brought, due to the wording of the respective laws prohibiting obeah. The charge against Theophilus Neil was framed straightforwardly, as was usually the case in Jamaica, as ‘practicing obeah’. Arthur and Mary Clement were both charged with ‘obtaining money by false pretenses with intent to defraud by the practice of obeah’, a charge that was more specific in directly naming obeah than were many Trinidadian charges, where the phrase used was frequently ‘obtaining money by the false assumption of supernatural power or knowledge’. This wording paraphrased text in the Summary Conviction Ordinance of 1868. In both cases the precise charge that was appropriate was discussed in court. The police hedged their bets in prosecuting Neil, charging him, in addition to practising obeah, with practising medicine without a licence. The Clements were initially charged with receiving money ‘under the pretence that they could restore [Mr Stewart] to health’ – effectively, a charge against the medical licensing law – but this was altered in court at the suggestion of the police to the charge already quoted. These shifts and multiple charges were common in obeah cases, because the offence overlapped with a range of other prohibitions and illegalities. The decision about which specific charge to bring lay initially with the police, and took into account the relative seriousness with which the law treated different offences and the charge that was most likely to result in conviction. The offence of breaching the medical law might be used if there was no explicitly ‘supernatural’ element to the ritual healing that had taken place. In addition, the Jamaican legal definition of vagrancy – like vagrancy legislation in many other parts of the Caribbean – included ‘pretending to use any subtle craft or device by palmistry or any such superstitious means to deceive or impose on any person’.Footnote 87 A conviction for ‘using superstitious means to deceive or impose’ might be obtained in circumstances where the more stringent requirements for a conviction under the Obeah Act had not been met. This produced a number of prosecutions under the vagrancy law that were understood by all concerned as obeah cases. For instance, the prosecution of Benjamin James (‘Benjy Two-Face’) for vagrancy was reported under the headline ‘An Obeah Case’.Footnote 88 Indeed, magistrates sometimes commented that a defendant was lucky to have been charged with vagrancy rather than obeah, because of the lesser punishment, or noted that if there had been further evidence they would have changed the charge to one of obeah.Footnote 89

As this discussion shows, police decisions about what charge to bring might not be final. An initial charge of obeah could be reduced to one of practising medicine without a licence, or vagrancy. A defendant's perceived class standing could soften a prosecution. Jane Philips, whose husband was a schoolmaster, was caught at 5 a.m. scattering what some said to be ‘a mixture of salt and grave-yard dirt and crushed bones’ – although others said it was merely salt – outside the entrance to a neighbour's house. She was brought to court to be prosecuted for obeah, but at the beginning of the trial the prosecuting lawyer asked for permission to reduce the charge, because Philips was ‘a respectable woman and a woman of some sense who, in his opinion, must certainly have lost her head when she committed so foolish, such an utterly nonsensical act’. The magistrate agreed, and Philips was bound over to keep the peace for three months.Footnote 90 While the obeah prosecution was unlikely to have succeeded in this case anyway, because there was no exchange of money or client–specialist relationship, it is notable that the argument made and accepted in court related to Philips's status rather than what she had done. On other occasions, cases that began as more minor charges were changed to obeah during the course of a trial. Robert Stone, for instance, was initially prosecuted for vagrancy because he had told a woman that an ‘iniquity’ was buried in her yard, and offered to kill the man who wanted to hurt her. The magistrate in the case, Mr S. C. Burke, ordered that Stone be prosecuted for practising obeah instead, because he ‘would very much like to give him a licking’. As it turned out, Burke did not get his way: at Stone's retrial that afternoon, presumably under a different magistrate, he received a punishment of two months’ imprisonment, which might well have been the outcome of the vagrancy trial.Footnote 91 Both examples show that the charge was not a straightforward consequence of the event that allegedly precipitated it, nor was it simply decided on by the police. Rather, it resulted from interactions among police, magistrates, and prosecution lawyers.

Once the initial charge was fixed, the defendant or defendants entered their plea. Most, including Theophilus Neil, Arthur Clement, and Mary Clement, pleaded not guilty. Indeed, those charged with obeah had a reputation for contesting prosecutions. In one case where a guilty plea was entered, the journalist reported surprise, ‘as obeahman normally fight their cases to the bitter end’.Footnote 92 The trials of the small group of defendants who did plead guilty were quick because little evidence was presented; the main question was the extent of punishment to be imposed. People pleaded guilty in the hope of obtaining a lighter sentence, as one defendant revealed when appealing against a sentence of twelve months’ imprisonment and twelve lashes, on the grounds that he had only pleaded guilty because a policeman told him that he would receive no punishment if he did not contest the charge.Footnote 93 Those who pleaded guilty in Jamaica do appear to have been less likely than those who did not to be sentenced to flogging, and were less likely to receive the longest possible prison sentences of twelve months. Nevertheless, the median term of imprisonment was the same as for all cases, at six months.Footnote 94