Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

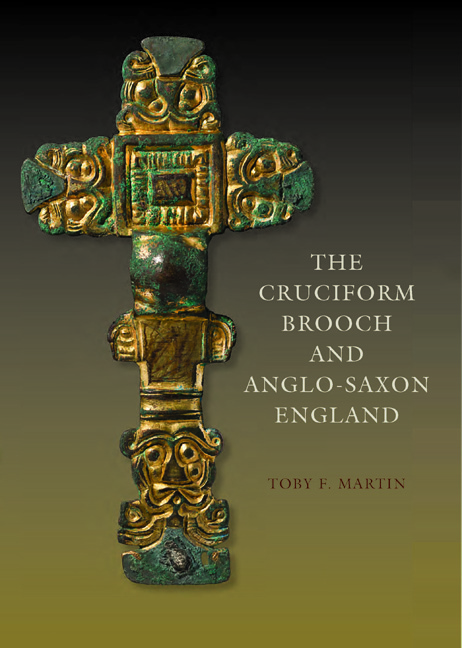

- 1 The Anglian Brooch par excellence

- 2 A New Typology for Cruciform Brooches

- 3 Building a Chronological Framework

- 4 Cycles of Exchange and Production

- 5 Migrants, Angles and Petty Kings

- 6 Bearers of Tradition

- 7 Cruciform Brooches, Anglo-Saxon England and Beyond

- Appendix 1 Cruciform Brooches by Type

- Appendix 2 Cruciform Brooches by Location

- Appendix 3 A Guide to Fragment Classification

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plate Section

5 - Migrants, Angles and Petty Kings

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2015

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Anglian Brooch par excellence

- 2 A New Typology for Cruciform Brooches

- 3 Building a Chronological Framework

- 4 Cycles of Exchange and Production

- 5 Migrants, Angles and Petty Kings

- 6 Bearers of Tradition

- 7 Cruciform Brooches, Anglo-Saxon England and Beyond

- Appendix 1 Cruciform Brooches by Type

- Appendix 2 Cruciform Brooches by Location

- Appendix 3 A Guide to Fragment Classification

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plate Section

Summary

In the previous chapter, I suggested that the production and exchange of objects like cruciform brooches created a world of material and social connections binding both objects and people into what we refer to as early Anglo-Saxon society. The question posed in this chapter is what kind of a society did cruciform brooches go toward creating? And within what kind of socio-political structures did they operate? Accordingly, this chapter asks what cruciform brooches can tell us about three of the most important historical processes of the fifth and sixth centuries: migration, the construction of ethnic identities and the formation of kingdoms. I refer to these aspects as historical because our knowledge of them stems from documentary sources, foremost among them Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica, Gildas' De Excidio Britanniae and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Indeed, it is the relationship between textual and material sources that provides some of the most intriguing and contentious problems of the period. Using a type of brooch to tackle these big questions is not an original approach, though it has not been utilised for some time. In a type of jewellery, as if in a nutshell, Edward Thurlow Leeds saw the migrations and establishment of Anglo-Saxons in post-Roman Britain. Though subsequent developments in archaeological theory make his work appear somewhat unsubtle, my methods ultimately take inspiration from Leeds' optimism in creating historical-archaeological narratives from a relatively small range of objects. The fact that such methods are still applicable attests to the richness of the socio-cultural information yielded by these items and their archaeological contexts.

Although Leeds took cruciform brooches as a direct representation of the Angles, supposedly an invasive culture and people from northern Germany, the simplicity of his work is occasionally exaggerated. Leeds was conscious that the situation was not quite that straightforward, being aware that material culture was not a direct indication of ethnicity and that the historical accounts should not be taken too literally. For instance, he explicitly questioned how much Bede would have really known about the earlier period.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cruciform Brooch and Anglo-Saxon England , pp. 161 - 190Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015