Introduction: Conflict Lines in the Shadow of the Transnational Cleavage

In the previous chapter, we shed light on the variety of policy responses to the refugee crisis starting in the spring of 2015 when the European Commission put forward the European Agenda on Migration. We have shown that in the shadow of joint solutions, including external rebordering, efforts toward burden sharing, and overhauling the largely dysfunctional Dublin regulation, significant conflict lines opened up between groups of member states on the one hand and between member states and European institutions on the other. This chapter zooms in on the role of domestic interests and the way they are articulated in national policy debates. Issues of migration and asylum are part and parcel of political actors’ conception of national and group identities, which, as we know from postfunctionalist integration theory (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe, Marks, Jones, Menon and Weatherill2009), serve as powerful battle cries in the hands of politicians to rally public opinion on their side either to politicize the European Union’s role in crisis management or to oppose national governments’ efforts to come to terms with the refugee crisis on their soil.

This self-conception of national- and group-based identities, however, matters politically only to the extent that they are activated by politicians and organized interests, leading to enduring cleavages that structure political competition (Bartolini Reference Bartels2005). Over recent decades, the cleavage structure that well described the “frozen” party systems of the postwar period in western Europe (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lorimer1967) gave way to a national cleavage pitting the winners of globalization and European integration against its losers (Kriesi et al. 2008, Reference Kriesi2012; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe, Marks, Jones, Menon and Weatherill2018). Within this integration-demarcation divide that manifests itself both in public attitudes and in political competition, immigration, rendered highly salient by the refugee crisis, can be regarded as a sort of “super-issue” with a potential to activate cultural and economic grievances simultaneously (Odmalm and Super Reference Oesch2014).

The key venue for political conflict around immigration is thus likely to play out in the partisan-electoral arena where radical right parties (RRPs), having made their first electoral breakthroughs in the 1980s, are well positioned to capitalize on their ownership of the issue, as their primary appeal lies in a nativist defense of the nation state against cultural threats from immigration (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Mudde Reference Mudde2013). However, the electoral success of these RRPs has prompted mainstream parties to engage in strategic responses to fend off this electoral threat, often by shifting their own programmatic position toward a more restrictive stance on immigration (Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Abou-Chadi, Green-Pedersen, and Mortensen Reference Abou-Chadi, Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2020). In the extreme, such strategic positioning can play out within the government itself in the case of coalitions, and especially grand coalitions (Engler, Bauer-Blaschkowski, and Zohlnhöfer Reference Engler, Bauer-Blaschkowski and Zohlnhöfer2019; Höhmann and Sieberer Reference Hooghe and Marks2020), where coalition partners not only compete with the radical right but also with each other in an effort to send credible signals to voters that their concerns are heard. These considerations together lead us to expect that the most common conflict line in the refugee crisis will play out in the partisan-electoral arena between political parties, with the government (and senior government parties) on one end of the conflict line and radical challenger parties, the mainstream opposition, and occasionally coalition partners – in the case of grand coalitions – on the other end.

However, the political representation offered by political parties is likely to be highly imperfect, ridden with conflicting pressures on parties in a multidimensional political competition (Odmalm and Super Reference Oesch2014). Especially center-left parties are expected to feel the pinch (Hinnfors, Spehar, and Bucken-Knapp Reference Hirschman2012; Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020), as they are trapped between the principle-based expectations of a left-liberal electorate and the threat of an exodus to RRPs of their traditional working-class voters. As center-left parties navigate this trade-off and other actors in the party-political space, such as radical left-wing competitors, can offer only limited representation for the pro-refugee electorate (or for refugees themselves for that matter), nonpartisan actors are likely to enter to fill the void. The most likely candidates for such a role are political actors that are driven less by electoral considerations than by humanitarian and legal principles, such as NGO groups, intellectuals, church actors, and more broadly speaking, civil society actors. While the mobilization of such actors in the context of the refugee crisis has already been documented in a number of countries that we study (see Majtényi, Kopper, and Susánszky Reference Manin2019 for Hungary; Kalogeraki Reference Kammermann and Dermont2020 for Greece; and Durán Mogollón, Eisele, and Paschou Reference Durán Mogollón, Eisele and Paschou2021 for Greece and Germany), we expect a more general conflict line to emerge between governments and such civil society actors as a result of the parties’ turn to more restrictive policy positions on immigration.

Furthermore, the national cleavage that we regard as the driving force behind conflicts related to the refugee crisis has an important international component, especially in the context of policy episodes with an inherently international dimension. In addition to domestic conflict lines, governments are thus likely to engage in conflict with international actors in line with the liberal intergovernmental perspective (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik1998; Hosli and Arnold Reference Hutter and Porta2010) that predicts an interstate cleavage will emerge as national governments seek to bring a unified “national position” to the negotiating table. In these debates, far from acting alone, member states are likely to seek transnational alliances to challenge EU initiatives, such as the V4 grouping’s steadfast opposition to the EU’s relocation scheme in the refugee crisis (Koß and Séville Reference Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen and Jones2020). Moreover, bilateral conflicts between individual member states are likely to arise as unilateral decisions of member states, such as rebordering efforts and waiving through asylum seekers, impose an additional burden on neighboring states in the form of redirected migrant flows and/or secondary movements (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Ferrera and Schelkle2021). Therefore, we expect two types of international conflicts to emerge: one between national governments and EU institutions and another between national governments of different member states.

Based on these theoretical considerations, we derive the following expectations for this chapter. As the foregoing discussion suggests, different types of policy episodes are likely to trigger different kinds of conflicts. In particular, we expect episodes revolving around border control measures to draw in international audiences and trigger international conflicts, whereas asylum-related episodes are more likely to be dominated by conflicts between the national government and its domestic opponents. Second, the structural position that countries found themselves in during the refugee crisis is also likely to be systematically linked to the emerging conflict lines. Those member states whose policy decisions are likely to impose negative externalities on other countries – namely frontline states and to some extent transit states – are more likely to trigger international conflicts than domestic ones. Third, within domestic conflicts, the underlying problem and political pressures that the national governments are confronted with are expected to be linked to the type of opponents of government policies. While the party-political opposition and civil society actors are “natural” opponents of governments – albeit for different reasons – the less common intragovernmental conflicts are more likely to emerge under conditions of intense problem and political pressures because only under such extreme scenarios may coalition partners risk a government breakdown for anticipated electoral gains, or at least for damage control. Lastly, different conflict lines are expected to imply different levels of politicization and levels of support behind the governments’ policies. On one end, international conflicts are likely to imply relatively high levels of politicization due to the wider range of actors involved in the debate, and relatively high levels of support behind government policies because domestic opponents may feel pressured to mute their opposition in the face of an international challenge. On the other end, societal conflicts are expected to be little politicized because nonpartisan actors face higher hurdles to keep the issue on the agenda compared to the party-political opposition. At the same time, intragovernmental conflicts are likely to imply the lowest level of average support behind governments because in addition to the usual sources of opposition, governments also need to confront criticism within their own ranks in these conflicts.

In this chapter, we build on these theoretical expectations to describe the main conflict lines that emerged in the national debates in the refugee crisis. To do so, we return to the forty policy episodes that we introduced and described in detail in Chapters 3 and 5. In the following section, we describe the broad actor types that we expect to act as protagonists in the conflicts. In the third section of this chapter, we introduce our conflict intensity indicator based on our PPA dataset and describe the episodes in terms of the average intensity of their conflict. In the fourth section, we first propose a simple and transparent measurement to allocate episodes to one of the conflict types that we introduced above: partisan conflicts, societal conflicts, international conflicts, and intragovernmental conflicts. We then proceed to provide a rough empirical test for the expectations that we derived, relying on descriptive comparisons only due to the limited number of cases, ruling out more rigorous statistical tests. The fifth section provides illustrations of these conflict lines from four selected episodes. The sixth concludes the discussion.

Governments and Their Opponents

In the original scheme of our PPA dataset, the national government is understood in a narrow sense. It comprises the heads of governments (premiers and the president in the semipresidential regime of France), the ministers, and other cabinet officials who are not affiliated with any particular ministry (e.g., spokespeople for the entire cabinet). By contrast, state institutions, local and regional authorities, and government parties are considered to be distinct actor types. For operationalizing conflict lines between actors, we partly relax this assumption by including government parties under the national government category. When a government MP in parliament criticizes the opposition, we would consider this a manifestation of a government–opposition conflict. Conversely, if a politician from the government party is addressed individually by civil society actors in a negative light, this would be counted as a manifestation of a government–civil society conflict.

Operationalizing the party-political opposition is comparatively straightforward. All actions undertaken by opposition parties regardless of their parliamentary presence or strength are considered as opposition actions and to the extent that they carry an element of criticism of the government, they contribute to partisan conflict. These actions can take the form of a statement by an individual politician from an opposition party or an action undertaken by the party as a whole (e.g., a motion in parliament). An important distinction we make, however, is between mainstream parties and challengers, following Hobolt and Tilley (Reference Hoeglinger2016). Within partisan conflicts, we thus further distinguish between conflicts dominated by government–mainstream opposition exchanges and those dominated by government-challenger opposition exchanges.

Civil society actors comprise a diverse group of organizations. The most common actor to enter the policy debates are NGO groups, such as Amnesty International and Médecins Sans Frontières, via either their international representatives or their local branches. In addition to these NGO groups, various expert groups, such as think tanks, academics, public intellectuals, and media representatives were also important opponents of government policies if not by virtue of their institutional powers, then by the moral weight of their words. Compared to these two broad groups, a relatively marginal role was played by business actors; churches; unions; and on occasions, migrants themselves who engaged in numerous protests and other confrontative actions involving policy demands, especially in Greece.

Opposition from international actors came from two main sources. On the one hand, EU institutions frequently intervened in domestic debates, especially when these debates were closely linked to EU-level policies, such as the Hungarian quota referendum that explicitly opposed the policy initiative of the European Commission. Even more prominently, foreign governments played an important role in some of the debates, especially in the case of border conflicts between neighboring countries, such as the stand-off at the French–Italian border (Ventimiglia), the French–British border (Calais), and the Austrian–Italian border (the Brenner Pass). In addition to these two main sources of international actors’ intervention, a smaller third group comprises other supranational institutions, such as the UN (UNHCR), the Council of Europe, and NATO.

Table 6.1 confirms the central role of the national government. In six of the eight countries (the two exceptions are France and Sweden), the national government was responsible for the largest share of the coded actions in the policy debates. When subsuming government parties under national governments, even these two exceptions fit the general pattern. As for the three potential opponents of governments, they have a roughly equal average share, with important cross-country variation, however. In France, Sweden, and the UK, the party-political opposition accounts for more than 20 percent of the actions. International actors are particularly prominent in the frontline states (Greece and Italy), and to some extent Austria and Hungary. Civil society actors are the most active in the UK and Sweden (and to a lesser extent in France). Germany stands out for the prominent role of government parties, suggesting that debates within the government, as we shall subsequently see, accounted for the lion’s share of the conflict.

Table 6.1 The distribution of broad actor types across the forty domestic refugee crisis episodes (column percentages)

| Broad actor type | Country | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | France | Germany | Greece | Hungary | Italy | Sweden | UK | Total | |

| International | 10.1 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 36.0 | 11.4 | 15.6 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 13.3 |

| National government | 32.8 | 26.4 | 35.8 | 38.2 | 31.4 | 42.2 | 21.1 | 31.9 | 32.9 |

| Other national | 23.4 | 27.3 | 11.2 | 6.8 | 9.3 | 23.7 | 22.8 | 7.8 | 15.8 |

| Government party | 11.2 | 4.0 | 32.1 | 2.3 | 18.0 | 1.1 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 10.3 |

| Opposition | 10.7 | 20.2 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 18.9 | 4.7 | 22.8 | 22.0 | 14.5 |

| Civil society | 11.9 | 15.0 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 22.1 | 27.0 | 13.2 |

| Total (%) Total (n) | 100 607 | 100 1,007 | 100 651 | 100 1,078 | 100 1,199 | 100 763 | 100 470 | 100 618 | 100 6,393 |

Considering the actors themselves, however, is only part of the story. Conflicts, by definition, have at least two actors involved, and our PPA dataset is well suited to pick up this link. In addition to the actors undertaking the actions, we thus also consider the actors who were most frequently targeted in the debates. Targeting can take place in multiple forms, but the most common form is an actor explicitly addressing another actor in their statements. Such targeting may not necessarily imply conflict, but in the empirical distribution of these targeted actions, only 15.6 percent are assigned a positive actor direction code, and the rest are either neutral (36.3 percent) or negative (48.1 percent). Therefore, to the extent that interaction takes place between actors, these interactions tend to have a conflictual bent.

When evaluating the importance of the actor types on the targeted end of the conflict lines (Table 6.2), the prominence of the national government is even more pronounced, accounting for an average of almost half of all targeted actions. Compared to the distribution of the actors undertaking the actions, international actors also appear to have a more pronounced role on the targeted end, suggesting that foreign actors – EU actors and other governments – were popular scapegoats in the policy debates (except for Germany, the UK, and Sweden, where their role was rather negligible). This is particularly the case in the two frontline states, where international actors appear between one third and half of the time among the target actors. Comparatively speaking, the other two broad actor types are less commonly targeted with a few exceptions, however. Opposition parties are targeted on numerous occasions in France, Hungary, and Sweden, whereas civil society organizations are the most commonly targeted in Germany and Sweden. Overall, however, the bulk of the attention is focused on the government, with the UK being an extreme case to illustrate this pattern: No less than 88.9 percent of all targeted actions are addressed at the national government.

Table 6.2 The distribution of broad targeted actor types across the forty domestic refugee crisis episodes (column percentages)

| Broad actor type | Country | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | France | Germany | Greece | Hungary | Italy | Sweden | UK | Total | |

| International | 29.7 | 23.4 | 8.0 | 47.2 | 22.3 | 37.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 24.7 |

| National government | 56.2 | 43.0 | 46.8 | 26.9 | 45.3 | 41.3 | 49.1 | 88.9 | 44.7 |

| Other national | 3.2 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 11.4 | 4.4 | 13.8 | 21.0 | 4.2 | 9.5 |

| Government party | 9.1 | 2.3 | 15.3 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 5.0 |

| Opposition | 1.8 | 12.1 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 12.3 | 0.7 | 10.1 | 1.5 | 6.4 |

| Civil society | 0.0 | 7.6 | 17.4 | 8.3 | 12.2 | 5.7 | 14.3 | 1.2 | 9.8 |

| Total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total (n) | 219 | 265 | 511 | 881 | 844 | 298 | 328 | 260 | 3,606 |

The Intensity of the Conflict

The actors involved in the policy debate, either as initiators (actors undertaking the actions) or as targets (actors addressed by the actions of other actors), reveal only one aspect of the conflict. To fully understand the nature of the conflict in a given policy episode, we need to make refinements both conceptually and in operational terms. First, a relatively small, but nontrivial share of the targeted actions are positive vis-à-vis the target actor, for instance, when actors praise other actors’ efforts toward finding a solution to the refugee crisis. Such positively targeted actions reduce the overall level of conflict in a given episode. Second, a large share of targeted actions are coded as “neutral,” such as when an actor calls upon another actor to act in a certain way without expressing explicit criticism of them. Third, even those actions that carry a negative attitude toward the target are assigned a negative actor direction code and as such vastly differ in the tone and the substance of the critique vis-à-vis the target. Fourth, among the nontargeted actions, some imply an escalation of the conflict, such as actions to veto or sabotage the policy and its implementation. These considerations taken together point to the need for an indicator that captures both the directionality of actors’ action vis-à-vis their targets (positive, negative, or neutral) and the type of actions they undertake.

We utilize our conflict intensity indicator for this purpose. For the present purposes, it suffices to say that conflict intensity is a composite indicator of actor direction (whether actors express a positive, a neutral, or a negative attitude vis-à-vis the target) and the policy action codes (the type of action that the actor undertakes). To illustrate the logic behind combining these two variables, for a given direction code vis-à-vis the target (let’s say negative), compare a personal attack to a policy demand: The level of conflict is expected to be higher when an actor launches a personal attack against the target (criticizes, accuses, or denigrates it) than when they merely demand a policy change.

Taking the average level of conflict intensity by episodes reveals that the episodes are broadly comparable, with the indicator in most of the episodes moving within a relatively narrow range between 0.4 and 0.6 on the 0–1 conflict intensity scale. A notable exception is Hungary, with four of the five episodes registering an average conflict intensity score of above 0.6. The Civil Law episode especially stands out for its high level of conflict (0.8). Ironically, the highest level of conflict intensity in the Civil Law episode (as well as in the very similar “Stop Soros” episode) occurred in a context where the debate had very little to do with the rules regulating the border and the asylum process. On the other end of the spectrum, cases of low conflict intensity cover a group of diverse episodes, such as the Summer of 2015 in Greece, the first Immigration Act in the UK, and two Border Control episodes in France (Ventimiglia and the General Border Closures).

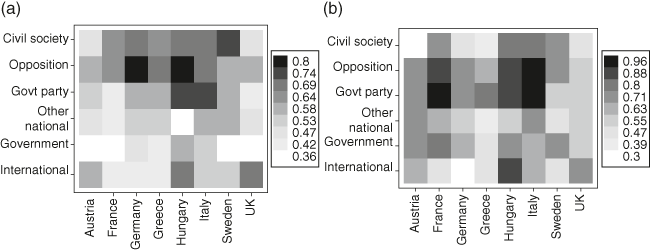

Since our conflict intensity indicator is action-specific, we can calculate the average conflict intensity scores by the initiating actors and the target actors. We illustrate this in Figure 6.1, with darker shades indicating higher average levels of conflict. Note that the color scales on the two heatmaps are not identical because when we restrict observations to targeted actions (Figure 6.1b), the average level of conflict intensity is likely to be higher.

Figure 6.1 Average level of conflict intensity by country and broad actor types as instigators (a) and targets (b)

Among the instigators, opposition parties and to a lesser extent civil society groups stand out from the rest, though the cross-country variation is substantial. Opposition parties instigate, on average, the most intense conflicts in Germany and Hungary, while civil society is the most conflictual in Sweden. Among the third broad type of opponents of government policies that we identified above, international actors are comparatively restrained, with the partial exception of Hungary (the relatively high average conflict intensity score for international actors involved in British debates results from very few corresponding observations). The most noteworthy result from this heatmap is the limited role of governments as instigators, arguably because the majority of government actions in the overall sample (58.6 percent) are nontargeted, as governments typically focus on the policies rather than on their opponents in their actions. Again, the partial exception is Hungary, where the government very often made critical remarks to their opponents. The restraint shown by most governments, however, needs to be somewhat nuanced when we include government parties, which often engaged in conflictual actions not only in Hungary but also in Italy and to a lesser extent Germany, Greece, and Sweden.

Government parties, therefore, often acted as the more militant arm of governments in the debates, as evidenced by the considerably higher average conflict intensity score in the parliamentary arena (0.54), the natural venue for these government party actors, compared to the governmental arena (0.41).

This difference between government parties and national governments is mirrored in the conflict intensity patterns by target actors. Though the average conflict intensity score among actions aimed at governments is considerably higher compared to actions instigated by governments, when government parties are targeted by their opponents, the average level of conflict tends to be even higher. Most importantly, however, actions aimed at opposition parties proved to be, yet again, the center of the conflict, with average conflict intensity scores above 0.8 in France, Italy, and Hungary. Civil society actors, by contrast, are largely spared as targets; their contributions to the overall level of conflict reside rather in their role as instigators. A partial exception from this pattern are Hungary and Italy, where civil society groups provided popular scapegoats for right-wing government officials because of their alleged role in helping asylum seekers reach the national territory. Finally, both as instigators and as targets, international actors tend to elicit relatively limited conflict intensity. The notable exception, yet again, is Hungary, where EU institutions – or in the case of the Fence Building episode, neighboring governments – often served as the prime target in the debates.

Conflict Lines and Their Correlates

Having outlined the main actors involved in the policy debate across the forty episodes as well as the average intensity of the conflict in each episode corresponding to our broad actor categories, we now return to the task set out in the introduction and identify the main conflict lines that prevail in each episode. To speak of conflict lines, it is imperative to restrict our PPA dataset to the subset of observations where target actors can be identified. As a first step, we rely on the same broad actor categories that we used up to this point – international actors, national governments, government parties, opposition parties, and civil society actors both on the initiator and on the target sides. We exclude other national actors (state institutions and local/regional authorities) from our analysis because of their relatively marginal role in the conflict, as evidenced by Figure 6.1. Theoretically, there are ten actor pairs involving two of the five actor types. However, we consider only the subset of conflict lines where the government is one of the actors. Moreover, we treat governments and government parties as the same actor at first – a restriction we drop later on in order to identify specific subtypes of intragovernmental conflicts.

The first step toward identifying conflict lines consists of calculating the share of targeted actions for each relevant pair. For example, we can calculate the share of all targeted actions in an episode involving the government and opposition parties. The measurement is symmetrical in the sense that governments targeting the opposition and the opposition targeting the government contribute equally to the strength of this conflict line. The second step in the measurement concerns the intensity of the actor pair–specific conflict, which we measure by the average conflict intensity score among the actions that involve a given actor pair. For each relevant actor pair, we then take the product of these two elements – the share of actor pair–specific targeted actions in all targeted actions and the average conflict intensity score of these actor pair–specific targeted actions. The product ranges from 0 (when either no actor pair–specific targeted action occurs in the episode or all the actor pair–specific targeted actions are of minimum conflict intensity) to 1 (when all the targeted actions are undertaken by the same actor pair and all these targeted actions are of maximum conflict intensity). We call this product the actor pair–specific conflict score.

Below, we concentrate on those pairs where one of the actors is the government. We also calculated the conflict scores for pairs not including the government, but these scores turned out to be considerably lower compared to the pairs involving the government. This is hardly surprising, given that targeted actions between civil society, opposition, international actors, and state and regional institutions are quite rare compared to actions where one of the actors is the government.

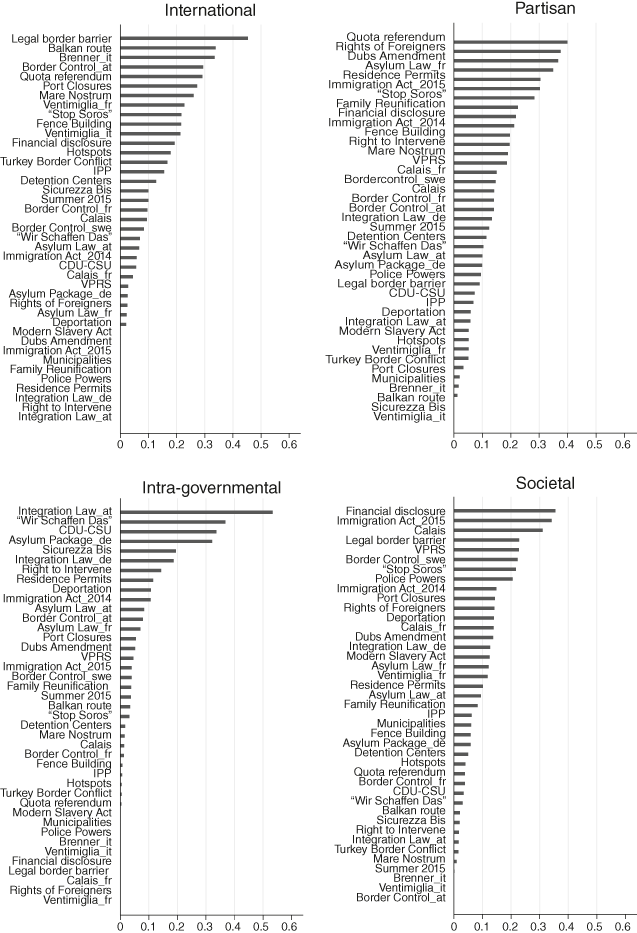

A quick look at Figure 6.2 reveals that the average strength of the four conflict lines differs considerably. Whereas the partisan and the societal conflict lines are present in almost all of the episodes, this cannot be said for the other two types of conflicts: intragovernmental and international. Especially intragovernmental conflicts appear to be the exception rather than the rule: Only in a quarter of the episodes does their strength exceed 0.1, and in another quarter of the episodes, there is no such conflict to speak of whatsoever. By contrast, only two of the forty episodes register a zero score for the partisan conflict line, and three of the forty episodes register a zero score for the societal conflict line. The average strength of the four conflict lines corroborates these differences. The average scores are 0.14 for partisan, 0.12 for international, 0.10 for societal, and 0.08 for intragovernmental conflicts. This provides some tentative evidence for our initial expectations that partisan conflicts are the most likely venue for conflicts in refugee-related policy episodes.

Figure 6.2 Conflict scores for the four dominant conflict lines in the policy episodes

With the episodes ordered according to the size of the respective conflict score, some of the ideal typical episodes in terms of the conflict lines can be identified. Thus, the Legal Border Barrier Amendment in Hungary stands out as an example for a conflict between the government and international actors. With respect to the conflict between the government and its partisan opposition, there is a more even distribution of episodes at the top, with the Hungarian quota referendum, the Rights of Foreigners Bill in France, and the Dubs Amendment in the UK involving the most intense partisan conflicts. Comparatively speaking, as we noted above, many fewer episodes register high conflict scores between government actors themselves. The Austrian Integration Law episode is a clear outlier here, and three of the five German episodes (“Wir Schaffen Das,” the CDU-CSU Conflict, and the Asylum Package) follow in second, third, and fourth place, respectively. Finally, three episodes stand out for their relatively intense conflict between governments and civil society actors: The Civil Law episode in Hungary, the second Immigration Act in the UK, and the Calais border conflict (on the British side).

Beneath these broad-brush characterizations of conflict lines, however, there are important nuances. For three of the four types of conflicts, we further distinguish between two subtypes each. Within international conflicts, the main conflict line can be either between the national government and EU authorities or between the national government and other governments. For partisan conflicts, the bulk of the opposition can come either from mainstream or from radical opposition parties. For intragovernmental conflicts, the main conflict can take place either between coalition partners in the case of coalition governments, or within the government (or the senior ruling party) itself. We shall call the former type coalition splits and the latter type government splits. We do not further distinguish between societal conflicts, partly because we consider it to be of secondary importance which type of civil society organization the main source of opposition is coming from. With this second-level splitting, we thus end up with seven subtypes within the four main types we have previously identified. Table 6.3 allocates each episode according to the prevailing conflict. For the identification of the subtypes, we simply reproduce the conflict scores for the subtypes and allocate the episodes depending on which subtype-specific conflict score is greater.

Table 6.3 The dominant conflict line across the refugee episodes

| Dominant conflict type | International conflict | Partisan conflict | Intragovernmental conflict | Societal conflict | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype | Government–EU | Transnational | Main opposition | Radical opposition | Coalition split | Government split | Societal conflict |

| Italy | Mare Nostrum | Ventimiglia Brenner Port Closures | Sicurezza Bis | ||||

| Greece | Hotspots Detention Centers | IPP Turkish border | Summer 2005 | ||||

| Hungary | Legal border barrier | Fence Building | Quota referendum “Stop Soros” | Civil Law | |||

| Austria | Border Controls Balkan Route | Asylum Law | Right to Intervene | Integration Law | |||

| France | Ventimiglia | Asylum Law Rights of Foreigners | Border Controls Calais | ||||

| The UK | Immigration Act of 2014 Dubs Amendment | Immigration Act 2016 VPRS Calais | |||||

| Germany | Integration Law | “Wir Schaffen Das” Asylum Package CDU-CSU | Deportation | ||||

| Sweden | Family Reunification (12/2018–7/2020) | Residence Permits Family Reunification | Border Control Police Powers Municipalities | ||||

Examining the dominant type of conflicts across countries and policy episodes, some interesting patterns emerge. Thus, in line with our expectations, international conflicts are mostly limited to frontline and transit states. Partisan conflicts dominate in at least one episode in six of the eight countries, but they are absent from Germany and Italy. Most partisan conflicts take place between the government and the mainstream opposition, suggesting that strategic behavior by mainstream opposition parties often succeeds in sidelining challenger parties from the debates. That said, in Austria and France, where two of the largest and most established radical right populist parties in the EU are key actors in the party-political space, three episodes are dominated by the conflict between the government and the challenger opposition (the FPO and the National Rally). Interestingly, most of the intragovernmental conflicts (five of the six episodes) are characterized by splits within the government, strictly understood, or between the senior government party and the government. There is only one episode (the Integration Law episode in Germany) that is dominated by a coalition split between the ruling parties. However, it must be noted that allocating the episodes within the intragovernmental category is highly sensitive to coding decisions (e.g., whether the government position or the party position enjoys precedence when coding individual actors). Finally, with one exception, government–civil society conflicts are restricted to destination states. The only exception is the Civil Law episode in Hungary, where civil society groups were explicitly targeted by the government.

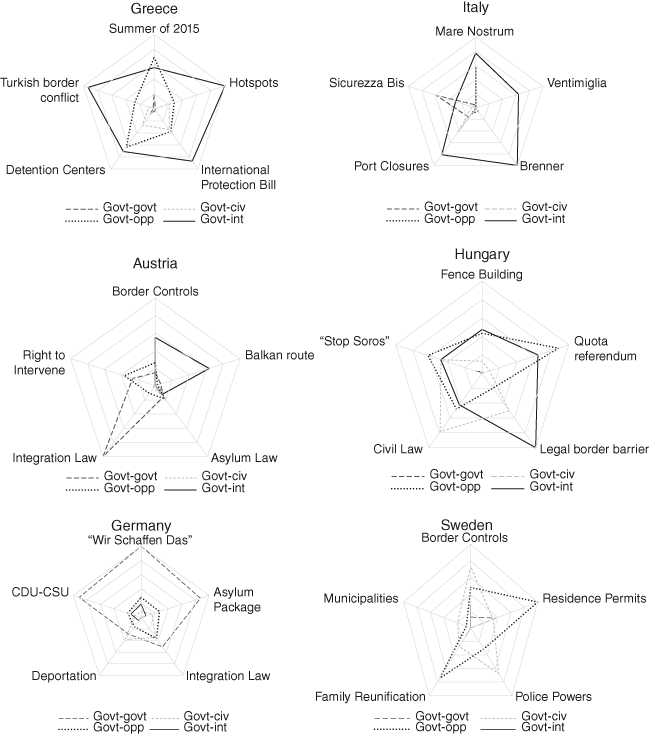

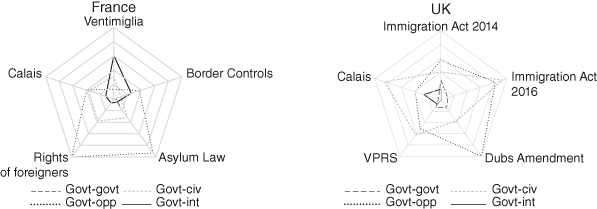

The disadvantage of treating episodes as belonging to one but only one conflict type is that we neglect possible secondary conflicts that may have strength that is comparable to the dominant conflict. To take the full configuration of country-specific conflicts into account, we present a series of country-specific radar plots (Figure 6.3) with episodes in the angles of the outer pentagons and the four rectangles showing the episode-specific conflict scores for each type of conflict. Starting with the frontline countries, the dominance of the international conflict line is clearly visible and is represented by the large area carved out by the black rectangles. In Greece, this international conflict primarily stems from the relatively important role of the European Commission in the debate and from the frequent exchanges between Greek authorities and foreign governments (mostly Germany and Turkey). In Italy, the international dimension of the conflict is primarily driven by Italian authorities interacting with neighboring governments (France and Austria) during the border conflicts at Ventimiglia and the Brenner Pass. In addition to this international dimension, a relatively large secondary conflict (government–opposition) is visible in Greece, whereas secondary conflicts appear only in individual episodes in Italy (e.g., the intragovernmental conflict in the case of the Sicurezza Bis episode).

Figure 6.3 Relative strength of conflict lines in policy episodes (by country type: frontline states, transit states, open destination states, closed destination states)

In the case of the two transit states, Hungary has three dominant conflict lines that are comparable in size; the international conflict line is the strongest overall, and the partisan and societal conflict lines are close seconds. In the international dimension, the European Commission and the European Parliament emerged as the Orbán government’s most vocal critics, whereas foreign governments contributed to the conflict mostly during the Fence Building episode. Within the partisan conflict line, the left liberal mainstream opposition played a much more prominent role than the right-wing challenger party, Jobbik. The societal conflict was largely driven by civil society groups that the government directly targeted in two of the five episodes (Civil Law and “Stop Soros”). By contrast, the intragovernmental conflict line is almost completely absent, due to the highly cohesive nature of the Fidesz-led government.

The strongest conflict line that emerges in Austria is the intragovernmental one, but it is heavily driven by a single episode, the Integration Law. During this episode, the national government and both members of the grand coalition (SPO and OVP) regularly engaged in verbal exchanges that were predominantly critical, accounting for around a quarter of all actions in the episode. In addition to these intragovernmental debates, the international conflict line (with EU institutions as well as with Germany and Balkan route countries) emerged as a secondary conflict, with partisan conflicts and societal conflicts lagging far behind.

Destination states show great variation in their conflict patterns. Germany is a paradigmatic case of the intragovernmental conflict, with a pattern similar to the Austrian Integration Law episode, except that this type of conflict persists throughout all five German episodes (around a third of all coded actions involve some sort of intragovernmental exchange). All components of the government triangle – the national government, the senior coalition member (CDU-CSU), and the junior coalition partner (SPD) – contribute to this conflict in roughly equal proportions. The other three conflict lines pale in comparison to this intragovernmental standoff in the German case. Sweden, by contrast, has a more balanced conflict configuration, with the partisan conflict playing the most prominent role and the center right opposition leading the attack against the center left government, occasionally complemented by exchanges with the challenger left (The Left Party) and the challenger right (Swedish Democrats). A secondary conflict line in Sweden is the one between the government and civil society, which unlike in the Hungarian case, largely involves media actors and other influential individuals in society.

In France, the partisan conflict is the dominant conflict line, with two important caveats, however. First, only a relatively low share of all actions (27.4 percent) are targeted, so the overall policy debate has a comparatively subdued level of conflict with the second lowest average conflict intensity among the eight countries (0.47). Second, the high partisan conflict score is driven by two of the five episodes: the Asylum Law and the Right of Foreigners Bill. During these two episodes, the mainstream opposition and radical challengers both from the left and the right contributed roughly equally to the partisan conflict. Finally, in the UK, there is a rough balance between the partisan and the societal conflicts, with the other two conflict lines largely absent. Within the partisan conflict in the UK, the opposition Labour Party led the attacks on the Conservative–Liberal Democratic coalition (later on, the single-party Conservative government), while the societal conflict was largely driven by various NGO groups (and to a lesser extent, religious figures from the Anglican Church) voicing their humanitarian concerns about the plight of asylum seekers in the restrictive policy environment of the UK.

Correlates of Conflict Lines

Having outlined the main conflict lines in the eight countries, we are now well placed to investigate systematic differences between these conflict lines in terms of the substantive scope of the episodes and the underlying political context. To briefly recall the expectations that we derived in the introductory section, we shall examine whether conflict lines systematically covary with the types of policy episodes, the underlying problem and political pressures, and the levels of politicization and average support behind the governments’ policies. Given the limited number of cases, we are unable to offer a rigorous statistical analysis across the episodes to answer these questions, but a descriptive summary provides some tentative answers nonetheless.

First, we investigate whether the substantive scope of the episodes offers any cues to the kind of conflict line that is most likely to emerge. We distinguish between the four types of episodes that we introduced in Chapter 4: border measures, changes in asylum rules, burden sharing episodes, and integration/return measures. It is readily apparent from Table 6.4 that international conflicts, unsurprisingly, are heavily concentrated among the border measures: All but one of the thirteen international conflicts correspond to this episode type. The other most common type of conflict, partisan conflicts, are more evenly distributed across the episode types, with the exception of integration and return episodes, all four of which triggered either societal or intragovernmental conflicts. While societal conflicts are evenly distributed among the episode types, none of the intragovernmental conflicts revolved around changes in asylum rules.

Table 6.4 The distribution of dominant conflict lines by types of episodes (frequencies and column percentages)

| Type of episode | Dominant conflict type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International | Partisan | Societal | Intragovernmental | Total | |

| Border episodes (%) | 92.3 | 38.4 | 33.3 | 50.0 | 56.1 |

| Asylum rules (%) | 0.0 | 23.1 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 12.2 |

| Burden sharing (%) | 7.7 | 38.5 | 22.2 | 16.7 | 22.0 |

| Integration/return (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 33.3 | 9.8 |

| Total n | 13 | 13 | 9 | 6 | 41 |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

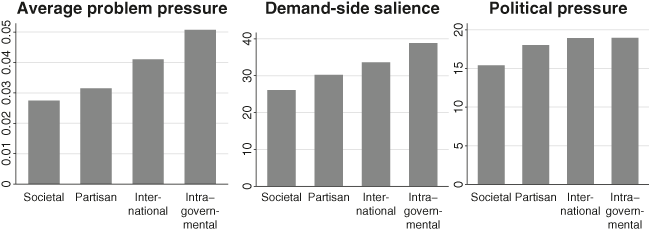

Turning to the demand-side correlates of conflict lines (Figure 6.4), problem pressure and demand-side salience appear to systematically differ between conflict types, whereas political pressure differs less. Intragovernmental conflicts stand out both in terms of problem pressure and salience from the rest, which is in line with our expectations. Though one has to interpret this with great caution because there are only six intragovernmental conflicts and they occur in only three countries, it appears that in contexts of high migration pressure and heightened public scrutiny, government actors are more likely to engage in public debate, crowding out other sources of conflict. Societal and partisan conflicts, on the other hand, tend to occur in contexts of significantly lower problem pressure and public salience, whereas international conflicts tend to occur at moderate levels in both dimensions. No such differences can be discerned with regard to political pressure, however, as all four types of conflicts tend to occur in roughly comparable political contexts as far as the strength of the radical right is concerned. A partial exception is societal conflicts in which the radical right seems somewhat weaker (by around 3 percentage points) compared to the rest.

Figure 6.4 Problem pressure, demand-side salience, and political pressure by conflict type

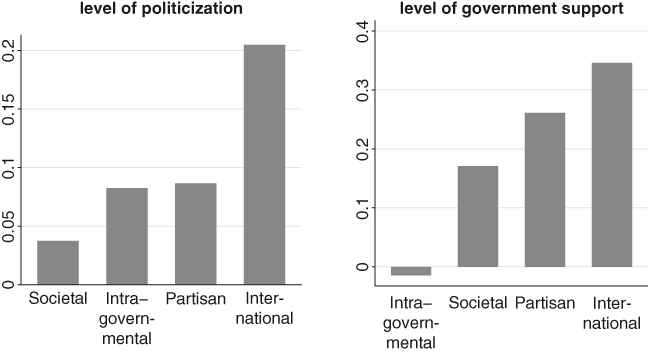

Compared to the political and migration context, there are considerably greater differences in the nature of the debate that the different conflict lines trigger. We focus on two elements of the debate that we have introduced in earlier chapters: politicization and average levels of support behind governments. On the left chart of Figure 6.5, we show the average level of politicization by conflict types, while on the right chart, we show the average level of support that the government received for their proposed policies. In both dimensions, international conflicts stand out from the rest with more than double the level of politicization and support behind governments compared to the other conflict types. The involvement of international actors thus seems to simultaneously lead to higher levels of politicization and to higher level of support that the government can expect. Our tentative explanation for this, as we laid out earlier, is that international conflicts tend to draw in a broader group of participants, thus increasing politicization, but at the same time, they tend to mute criticism from domestic opponents in the face of an international challenge. On the other end of the spectrum, societal conflicts tend to score low in politicization, while intragovernmental conflicts uniquely register a negative average level of government support. It appears, therefore, that as parts of the government (coalition partners, individual ministers, parliamentary wings of ruling parties, etc.) turn against the government proposal, they swell the ranks of critical voices, thus lowering the average level of government support. The low level of politicization in societal conflicts in turn is arguably the result of civil society actors’ institutional constraints and limited capacity to keep the debate on the agenda for an extended period of time and to draw in a wider array of actors in the debate.

Figure 6.5 Average levels of politicization and support behind government policies across the policy episodes

Conflict Lines in Detail

International Conflict: Legal Border Barrier Amendment in Hungary

The episode that best illustrates the type of international conflicts that occurred during the management of the refugee crisis unfolded in the spring of 2017 in Hungary. After a series of fence construction drives and a set of legal measures to hinder illegal crossings mostly across the Serbian and to a lesser extent the Croatian and the Slovenian borders, the Orbán government tightened the screws further by opening the way to the forced detainment of refugees and their confinement in metal containers under abject humanitarian conditions. This episode, while comparatively short and low in action count, constitutes a perfect example of an international conflict as the Hungarian government found itself in opposition to multiple sources of external contestation: EU institutions, the Council of Europe, the European Court of Human Rights, the UN, and other supranational institutions. Contrary to the Fence Building episode in the summer and autumn of 2015, there was no involvement of neighboring governments in the policy debate this time, arguably because they had come around to acquiesce to the sealed Hungarian borders as a fait accompli.

The exchanges between the Hungarian government and EU- and supranational institutions, however, were intense and conflict-ridden. Overall, the episode registers by far the highest conflict score on the international dimension (0.45 versus a sample average of 0.12). In fact, more than 40 percent of all actions in the episode involved exchanges between the Hungarian government and these international actors, and a majority of these actions carried a critical attitude toward the target actor. The directionality of these exchanges was rather lopsided, with the Hungarian government being the most common initiator (71.1 percent of the time) with the EU or EU institutions being the most common targets (60.5 percent of all such government–international exchanges).

On the Hungarian side, many of the attacks on European institutions and officials came from the highest circle and involved Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his closest entourage. In fact, Orbán himself undertook the very first action in this episode in February 2017: While defending the proposed detention plans, he criticized Brussels in an interview as being aloof to the “bloody reality” in Europe stemming from illegal migration. His criticism was later echoed by his chief security adviser, who accused the EU of double standards and a failure to appreciate the importance of protecting external borders. Other ministers, including the foreign minister and the justice minister, joined the fray with the common underlying narrative that while Hungary was protecting Europe, the EU had failed to live up to its responsibilities in the domain of border protection.

Other fronts of the offensive involved particular EU institutions and officials. In late March, the chief security adviser expressed “puzzlement” over a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights related to the transfer of unaccompanied minors from their care facility. Later in March, the prime minister’s office criticized the European Commission for its lack of flexibility and compromise on the issue of DNA testing of unaccompanied minors to verify their age. Simultaneously, attacks were launched on actors from the European Parliament (specifically, the Socialist Group) for passing a resolution against Hungary, which Janos Lazar, a prominent cabinet member, shrugged off as a “left-wing political provocation.” The most popular boogeyman among these offensives, however, turned out to be Judith Sargentini, a Green MEP from the Netherlands, for her role in getting another critical resolution passed by the European Parliament in 2018. In this later phase of the episode, the conflict was more sporadic but no less intense in its tone. For example, in September 2018, Gergely Gulyas, minister of the prime minister’s office, dismissed the Sargentini Report in parliament as a “false immigration indictment and slander.”

Comparatively speaking, the attacks on Hungary by EU- and supranational actors were more measured in tone but equally critical in substance. In late March 2017, the Council of Europe (CoE) called on Hungary to review its new migration law because it carried the risk of subjecting minors to sexual exploitation. A month later, it accused Hungarian authorities of being unable to differentiate between victims of human trafficking among illegal asylum seekers and refugees. Among EU actors, it was mostly the European Parliament and left-wing parties and MEPs within (including Sargentini herself) who led the wave of critical voices against Hungarian authorities because of the humanitarian conditions reigning in the transit zones after the legal changes. The European Commission also contributed to the conflict, however, via two critical interventions by Dimitris Avramopolou, the migration commissioner, in the spring of 2017. All in all, however, these critical remarks mostly concerned the specific provisions of the law and practices by the coercive authorities, in contrast to the much broader and personal critiques articulated by Hungarian officials. The conflict was therefore rather one sided both in terms of the scale of the attacks and in terms of its substance, with the Hungarian government clearly in the initiating seat. Moreover, compared to the international aspect of the conflict that we have outlined above, critical exchanges with the opposition and civil society were few and far between.

Partisan Conflict: Rights of Foreigners Bill in France

Compared to the Hungarian border episode discussed above, the Rights of Foreigners bill in France was only moderately conflictual, with an average conflict intensity score of 0.45. Moreover, in line with the demand-side and supply-side correlates we have shown above, it occurred in a context of low problem pressure (stemming from France’s role as a closed destination country), moderate demand-side salience (it ended before the Bataclan and the Nice terror attacks shocked French political life), and low politicization. Only in political pressure did the episode score above the sample average, mostly due to the continuously high level of political support enjoyed by the right-wing challenger National Rally in the run-up to the refugee crisis when this episode was on the political agenda (2013–15).

In its substance, this episode concerns two legislative changes initiated by the center left Holland government: an asylum reform to reduce the processing period of asylum applications from 24 to 9 months and an immigration law involving the creation of a multiyear residence permit so that foreigners could avoid having to go to the prefecture every year to renew their residence permits. Its duration was accordingly rather long, spanning two and a half years between the summer of 2013 and November 2015.

Two features of the French political context provided fertile grounds for partisan conflict. First, the two legal changes were initiated by a center left government that quickly found itself in a partisan cross-fire between the left (left-wing challenger parties) and the right-wing opposition (the Republicans as the mainstream opposition and the National Rally as the right-wing challenger opposition). In this particular policy debate, however, the National Rally played a secondary role, and the main conflict line was mostly between the government and the Republicans, and to a more limited extent, between the government and left-wing challenger parties, such as the Parti Radical de Gauche and the New Anti-Capitalist Party led by the self-proclaimed Trotskyite Olivier Besancenot. Second, the bicameral French legislative process ensured that the government would be exposed to partisan attacks at two separate legislative readings for each of the two reforms: first at the Assembly and second at the Senate.

The bulk of the conflict originated from opposition parties targeting the government. The left-wing challengers emphasized principles of individual liberty and humanitarian considerations. For instance, Olivier Besancenot criticized the government for racist and xenophobic practices upon the evacuation of a migrant camp in Paris. Meanwhile, the mainstream opposition emphasized concerns related to illegal migration and accused the government that its legal proposals did not go far enough, especially with regards to the second bill on foreigners’ rights. During the debate on the first bill, Eric Ciotti from the Republicans expressed broad agreement with the principle of reducing the application time for asylum claims but claimed that “if it serves to receive more people, it is not certain that the French people like this policy.” Les Républicains continued their opposition throughout the parliamentary readings of the second bill. A group of MPs from the Republicans criticized Bernard Cazeneuve, the interior minister standing behind the proposals, in a National Assembly debate, claiming that the text is “contrary to the national interest.”

In response, the government, mostly represented by Cazeneuve, also turned its attention to the right-wing opposition in general and to former president Sarkozy, an old–new presidential hopeful at the time, in particular. In the early stages of the debate in 2014, he claimed in an op-ed article that the former president was still struggling with “his old demons” on immigration, “scorning the facts” by “demagogy.” Later, on the sidelines of a study day on asylum reform organized by the National Federation of Associations for Reception and Social Reintegration (FNARS) in September 2015, he took aim at Sarkozy’s hardliner proposals once again, claiming that “refugee status is not divisible, it is one and indivisible like the Republic.” Overall, however, despite the government’s best efforts to defend its initiatives against attacks from both the left and the right, it struggled to escape from this partisan cross-fire in a context of sagging popularity at the polls. Its only solace was the fact that neither international actors nor civil society actors were particularly vocal in this episode and could not match the critical voice of the parliamentary opposition. Also, the government managed to maintain a semblance of unity in the public eye, presenting a united front against the opposition in the midst of this partisan conflict.

Societal Conflict: Immigration Act 2016 in the UK

The 2016 Immigration Act in the UK, the second set of reforms to the British asylum system within two years, scores the second highest on the societal conflict dimension, just behind the Civil Law episode in Hungary. However, given the fact that this episode is a comprehensive reform package rather than a direct and targeted assault on civil society, we consider it more interesting than the Civil Law episode for the illustration of societal conflicts in the context of refugee crisis management.

In terms of the demand-side and supply-side correlates, the conflict took place in an environment of low problem pressure (the UK had to deal with one of the lowest average levels of monthly claims relative to its population), low political pressure (although UKIP was polling strongly in the period before the Brexit referendum, it had not reached its peak yet and did not even come close to the electoral strength of right-wing challengers elsewhere, such as France and Austria), and moderate demand-side salience of immigration. The episode was not particularly politicized (its average politicization score is well below the sample average), and the government received a low level of average support for its initiative. Though the government itself stayed largely united throughout, both the parliamentary opposition and civil society actors took a resolutely hostile and critical stance toward the proposal. However, the intensity of the conflict with civil society was higher, not least because the leader of the parliamentary opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, tried to strike a cautious tone in his criticism of the bill, fearing an exodus of Labour voters to UKIP.

The conflict between the government and civil society was entirely unidirectional, with all such exchanges being initiated by civil society and targeting the government. Being shut out of the institutional venues for voicing their opposition, these civil society actors communicated via the media and collected numerous petitions against the government. Different groups, often in coordination with each other, focused on different aspects of the bill. Some of the criticism from media actors and landlord organizations concerned the Right to Rent scheme and the expected discrimination that tenants would face as a result. The social workers’ union demanded appropriate funding of specialist social and health care support for refugees and asylum seekers, accusing the government of turning a blind eye to children in particular. Business leaders accused the government of “taxing talent” in relation to the visa levy for companies employing foreign workers. The Scottish Refugee Council emphasized issues of regional competences and institutional prerogatives, accusing the government of treating devolved administrations as “second class” because of its attempt to circumvent the Scottish parliament in key areas of housing, child protection, and licensing.

Ultimately, none of the criticism against the government proved particularly effective, perhaps because of the cautious and restrained attitude of the parliamentary opposition; the lack of involvement of international actors; and the general honeymoon period that David Cameron’s single-party government enjoyed at the time, just a few months after its reelection in May 2015. Nevertheless, the episode illustrates the potential vulnerability of governments to societal conflicts in complex policy episodes that touch upon a multitude of issues, drawing a large number of stakeholders and opponents into the debate.

Intragovernmental Conflict: “Wir Schaffen Das” in Germany

When on the eve of September 4 German chancellor Angela Merkel made the fateful decision to suspend the Dublin regulation and leave the southern border with Austria open to Syrian refugees traveling to Germany via transit countries, she made one of the most controversial policy decisions during the whole refugee crisis, splitting German society (and the wider European public for that matter) to its core. One of most unique features of this episode – “Wir Schaffen Das” – for the purposes of this chapter is the main locus of conflict being within the government, as opposed to the international, partisan, and societal conflict lines we have presented above. This intragovernmental conflict pitted three main actors against each other: the national government; the grand coalition partner (SPD); and perhaps most importantly, the Bavarian sister party of Merkel’s CDU, the CSU. Most prominently, Horst Seehofer, leader of the CSU and Merkel’s most influential critic, proved to be the protagonist in this conflict line both as initiating actor and as a target of his opponents, including Merkel herself.

The episode took place in the very center of the refugee crisis, both in terms of space (Germany received the highest number of asylum claims in absolute terms) and in time (autumn 2015, the peak of the crisis). Accordingly, the conflict was met with high problem pressure and demand-side salience. Political pressure, on the other hand, was comparatively low because the right-wing challenger party AFD would begin its steady rise in the polls only after this episode. Though politicization remained moderate, the government nevertheless received the lowest level of support for its policies (–0.21) among all the episodes, a general feature of such intragovernmental conflicts.

Zooming in on the intragovernmental triangle, the most common initiator of these exchanges is the senior ruling party (mostly the CSU, represented by Seehofer, and to a lesser extent the CDU), accounting for 47.1 percent of such exchanges, with the junior member in the grand coalition, the SPD, in second place (33.8 percent) and the national government accounting for a mere 19.1 percent. On the target side, however, the government found itself in the center of the attacks, accounting for 72.1 percent of all targeted actions, with the senior ruling party (again, mostly the CSU) in second place. The SPD, on the other hand, was largely spared attacks in this intragovernmental conflict, with only a single action targeted against it.

The role of Seehofer in the conflict deserves special attention. He engaged in critical action against the government no fewer than ten times, with all of these actions being targeted at Merkel personally. He first personally entered the debate after a successful petition by CDU-CSU members to reintroduce border controls at the Austrian border, with the important caveat that refugees would still be allowed to enter the country upon registration. On the day of the closure (September 14), he criticized Merkel in an interview with Der Spiegel, calling her earlier decision to open the border “a mistake that will haunt us for a long time to come.” He continued his attacks in October, claiming that “a new order and new content [were] necessary at a government-level.” This statement was interpreted by many as a de facto vote of no confidence in the chancellor. Later that month, he went further by threatening to issue a complaint of unconstitutionality against the federal government, followed by an ultimatum targeting Merkel that pressured her to slow down the flow of refugees. It was not just Seehofer, however, who contributed to the conflict from the CSU’s side. Other prominent names included Edmund Stoiber, a previous Bavarian premier and chancellor candidate; Thomas Holz; and Michael Müller.

The government and its CDU allies tried to hold the ground in the midst of these attacks. First, Merkel simply tried to dismiss Seehofer’s critiques, sticking to her line on humanitarian grounds. Later, she sharpened her tone and engaged in public dialogue with him. For instance, in response to Seehofer’s threat of issuing a complaint of unconstitutionality, she rebuked him with a public letter, claiming his “accusations are invalid.” In mid-October, one of her closest allies in the CDU who would become a chancellor-hopeful for a brief period of time later on, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, rushed to Merkel’s defence in a thinly veiled attack on Seehofer in an interview. She stated that “as politicians it is not our responsibility to fuel fears, but to devise solutions for impending problems.”

During the conflict between Seehofer and Merkel, the junior coalition partner, the SPD, took a cautious stance on Merkel’s side. Their critical remarks were mostly aimed at Seehofer instead. In the early stages of the episode, Dieter Reiter, the SPD mayor of Munich, explicitly endorsed Merkel’s “Wir Schaffen Das” idea. Upon the reintroduction of border controls, SPD secretary general Yasmin Fahimi harshly criticized Seehofer for inviting Hungarian premier Viktor Orbán for a meeting, in what she described as a “stab in the back of Merkel.” The chairwoman of the Young Socialists in the SPD (Jusos), Johanna Uekermann, went even further and recommended that the CSU consider leaving the coalition government. That said, the SPD’s attitude toward the government was hardly without a critical undertone. Reiter criticized the interior minister, Thomas de Maizière, claiming that “the humane and dignified treatment of hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in Germany is a national task, and so far Berlin has not risen to the challenge.” Minister President Malu Dreyer from Rheinland-Pfalz reiterated the SPD’s support for Merkel’s “Wir Schaffen Das” but at the same time criticized the chancellor in an interview for failing to maintain discipline in the coalition. The SPD’s rhetorical strategy illustrates, among other things, that nongovernment actors can contribute to the conflict even if they are in agreement with the policy initiative in substance.

All in all, the “Wir Schaffen Das” episode was a paradigmatic example of an intragovernmental conflict with multiple actors stuck in a tug-of-war in a situation of high problem pressure and public salience. Ultimately, Merkel would emerge from this conflict politically weakened, paving the way for the AFD to emerge as a strong right-wing challenger party in the German political scene.

Conclusion

As we have shown in this chapter, the domestic responses to the refugee crisis in the period between 2013 and 2020 exposed vastly different conflict lines running through European societies. In particular, we argued that the integration–demarcation cleavage that rose to prominence in the context of the refugee crisis triggered four types of conflicts throughout the policy debates. The two most common types of conflicts were partisan conflicts on the one hand and international conflicts on the other. In international conflicts, national governments found themselves in opposition to EU actors, foreign governments, and/or other supranational institutions such as the UN. Such conflicts were almost the exclusive remit of Border Control episodes. Partisan conflicts, on the other hand, covered a more diverse set of episode types. In these episodes, mainstream opposition parties emerged as the most common adversaries of national governments, though on occasion they were aided by the challenger opposition both from the left and especially from the right. However, in particular cases as we have shown via the example of the Rights of Foreigners Bill in France, the left-wing challengers were somewhat more active in the debate than the National Rally, though all challenger parties paled in comparison to the mainstream opposition’s (The Republicans) contribution to the conflict.

Comparatively speaking, societal and intragovernmental conflicts were fewer. Societal conflicts are characterized by a stand-off between governments and civil society groups that comprise a wide array of different actors, such as NGOs, experts and academics, unions, religious institutions, or groups of migrants themselves. In our policy episodes, NGOs proved to be the most common type of such civil society actors, and our brief summary of the 2016 Immigration Act in the UK has revealed the type of civil society organizations that played the central role in this societal conflict line. Finally, the intragovernmental conflicts are the fewest but arguably the most intense, as is evidenced by the low level of support that governments received for their policies in their wake as well as the high levels of problem pressure and public salience that tend to accompany them. These conflicts mostly occurred in Germany and to some extent in Austria and Italy. Via our summary of this type of conflict taking place in the context of the “Wir Schaffen Das” episode in Germany, we have shown that this conflict can occur via multiple channels: either between the coalition partners (coalition splits) or within the government (and within the senior ruling party). In the “Wir Schaffen Das” episode, both of these channels were present, but in other episodes, one of the two is likely to dominate. We shall further elaborate on the details of such conflicts in Chapter 7 of this volume.

Though we have adopted a stylized categorization of episodes in terms of the dominant conflict line that prevails in each, in reality, many of the episodes were driven by multiple conflicts that simultaneously unfolded in them. Hungary, the country that stands out for its high level of overall conflict intensity, is the paradigmatic case for such parallel conflicts with three of the four conflict lines – the international, the partisan, and the societal – at comparable strength. These parallel conflict lines are perhaps the most important feature of the refugee crisis at the domestic level. In contrast to the EU-level conflicts that largely unfolded between member states and EU institutions, as we shall show in the next chapter, the domestic debates revealed a much more complex reality with a diverse set of actors involved. Throughout the refugee crisis, governments were trapped in a two-level game, with their bargaining power in the European arena conditioned by the type and the intensity of conflict they faced from domestic stakeholders – with the fate of the millions of refugees making their way to the EU in the balance.

Introduction

In this chapter, we present the actors and conflicts at the EU level. The study of these aspects of the crisis management includes the analysis of the actors and conflict configurations in the different episodes as well as the politicization of the episodes. We begin by introducing expectations about the actors and conflict structures at the EU level, which reiterate some considerations we have already introduced in Chapters 1 and 2. Next, we proceed to presenting the actor distributions and conflict structures in the six EU-level episodes. In a third step, we show how the various episodes have been politicized by the different actors and adversarial camps that we identified previously, overall and in the two key phases of the refugee crisis – the peak phase preceding the conclusion of the EU–Turkey agreement and the phase following the adoption of this agreement.

As we have argued in Chapters 1 and 2, in the multilevel polity of the EU, the supranational level is not just another level at which international agreements are negotiated to be subsequently implemented nationally. Polity membership creates a foundational interdependence that stems from the original choice to become a member of a compulsory association. Market integration and the extensive pooling of core state powers have increased this interdependence over time. Still, the EU is not a full-fledged federal system, and the degree of interdependence varies by policy domain. As we have observed in Chapter 4, in the domain of asylum policy, responsibility is shared between the EU and its member states. While the latter have retained core competences, their policymaking still depends on the common Schengen–Dublin framework. Moreover, the policy-specific legislative framework is embedded in the overall institutional structure of EU decision-making. In asylum policy, the mixture of interdependence and independence of the member states imposes reciprocal constraints on the decision-makers at each level of the EU polity: On the one hand, the interdependence restricts the possible policy responses of national policymakers, and on the other hand, the independence that national policymakers still enjoy constrains the decision-making at the EU level. The limited competence of the EU in the asylum domain poses a great challenge for joint EU policymaking in times of crisis.

In terms of relevant actors, the grand theories of European integration locate the power alternatively in the supranational agencies – the Commission (neofunctionalism) or the European Council (new intergovernmentalism) – or in the member states (liberal intergovernmentalism, postfunctionalism). Given the low capacity and lack of policy resources of supranational institutions in the asylum policy domain, we expect supranational entrepreneurship to be highly constrained (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2005: 362–363). Under such conditions, the success of the policy proposals by supranational actors depends on the support by the member states. In the case of the refugee crisis, opposition to joint solutions and conflicts between the member states have been reinforced by two conditions: First, the member states were asymmetrically affected by the crisis and unequally prepared to deal with it. While the frontline and open destination states, the states directly hit by the crisis, favored joint solutions, the bystander and to some extent also the transit and closed destination states were less affected by the crisis and therefore were less ready to share the burden (Noll Reference Odmalm2003; Bauböck Reference Bauböck2018). Second, joint action was constrained, and conflicts between member states were reinforced by the politicization of national identities produced by the uneven distribution of crisis pressures within the EU polity. Consistent with the predictions of postfunctionalism, the tension between the uneven distribution of costs and benefits of crisis resolution at the international level and the limited scope of community feelings at the national level has made opposition to EU policy proposals more vocal. As pointed out by Ferrara and Kriesi (Reference Ferrara and Kriesi2021), this decision-making scenario is consistent with the postfunctionalist notion of “constraining dissensus.”

It is the territorial channel of representation in the EU that provides the most important (although not the exclusive) conduit for the politicization of the reciprocal constraints and related conflicts. Accordingly, intergovernmental coordination has become the key decision-making mode in the EU in general, and particularly in crisis situations. In this mode of decision-making, the heads of member state governments (in the European Council) and responsible ministers (in the Council of Ministers) assume a decisive role. They provide the critical link between the two levels of the EU polity. As a result of their dual role – that of head of state or government representing a country in European negotiations and that of member of the European Council representing Europe back home – the executives of the member states become the pivotal actors in the two-level game linking domestic politics to EU decision-making. Accordingly, we expect the governments of the member states and their key executives to play a crucial role not only in domestic policymaking in the refugee crisis but also in policymaking at the EU level.

Under crisis conditions, the role of key executives of both the EU and member states is likely to become even more prominent. Under such conditions, which combine high political pressure in the sense of conflict-laden salience with high time pressure (urgency), executive decision-making is expected to become the preferred mode of decision-making both at the supranational and the national level. In a crisis, policymaking is no longer confined to the policy-specific subsystem (asylum policy in our case); rather, it becomes the object of macro-politics or “Chefsache,” to be taken over by the political leaders who focus on the issue in question. The decision-making mode of intergovernmental coordination corresponds to the EU-specific version of executive decision-making.

Foremost among the expected conflict lines are the vertical and transnational conflicts involving member states and the EU. In Chapter 2, we have formulated some expectations about these conflict lines. At this point, we reiterate the general expectations formulated in Chapter 2. In the short run, that is, in the early phases of the crisis, we expect open destination and transit states to share a common interest in stopping the flow of arrivals and in sharing the burden of accommodating refugees, which aligns them with the frontline states but opposes them to the restrictive destination states and the bystander states. While at first the transit states’ interests are clearly in line with those of the open destination and frontline states, the position of transit states is likely to get more ambiguous as the crisis progresses, since they clearly benefit from the secondary movements of the refugees within the EU. Moreover, the frontline and destination states are also divided with regard to the reform of the CEAS: Together with the other member states, open destination states are in favor of restoring the Dublin regulation, while the frontline states demand reform of the CEAS to share the responsibility for accommodating the flood of new arrivals.