It was late August 1847 when Fritz Rasmussen’s parents left the island of Lolland along with their six children. Fritz’s father, Edward, decided to emigrate to America in pursuit of “liberty and equality,” which he found sorely lacking in Denmark.Footnote 1 The year before, one of the Lolland’s social reform leaders, C. L. Christensen, had also emigrated to America, and the reason was believed to be the Danish authorities’ harsh treatment of dissidents who advocated on behalf of smallholders and peasants.Footnote 2

By 1847, Fritz Rasmussen’s father was also engaged in political activity in opposition to the Danish authorities to such a degree that both political necessity and economic opportunity prompted his decision.Footnote 3 On Lolland, where the Rasmussen family resided, land shortage was acute. In one county, Maribo Amt, 87 percent of all land belonged to properties larger than 4.4 acres.Footnote 4 It was therefore no coincidence that Fritz Rasmussen, looking back from the vantage point of 1883, used the language of the oppressed and stressed the importance of emancipation:

He [Father], I afterwards came to understand, had to leave the Country, like many others, as a political refugee – : on account of his writings & doings, for and among the communalities, in regard to a more & thorough emancipation of the people generally, from the oppressive Sovereignty of the nobility.Footnote 5

Edward Rasmussen’s family emigrated on August 27, 1847, two months after Martha Clausen’s brother had written to Claus Clausen to ask about emigrant prospects in Wisconsin, but the family did not see Clausen’s cautionary letter.Footnote 6 Where Claus Clausen had been guaranteed employment at arrival, the Rasmussen family’s future was from the outset more precarious.

In Fritz Rasmussen’s account, the family stopped briefly in Hamburg (then a sovereign state in the German confederation), boarded the ship Washington, and arrived in New York City on October 26. From New York the family travelled to Albany where the recently constructed Erie Canal originated. A few weeks later they boarded the Atlantic in Buffalo to be transported over the Great Lakes to Wisconsin (see Figure 4.1). Only later did they realize their good fortune. One of the next ships that went west over Lake Erie and Lake Huron was Phoenix, a modern steamer named after the bird in Egyptian mythology. But in contrast to the legend, Phoenix never rose from the ashes in November 1847. Instead, hundreds of Dutch emigrants lost their lives in the flames or icy water on their way to a new Midwestern home.Footnote 7 “We were spared the suffering and catastrophe,” remembered Fritz Rasmussen.Footnote 8

Figure 4.1 Fritz Rasmussen, born on the island of Langeland, emigrated with his family to Wisconsin in 1847 and eventually settled in New Denmark.

While the Rasmussen family’s ship made it unscathed over the lakes, the family did not. Nine-month-old Henry died of disease shortly before they reached Milwaukee on a “cold, bleak” November day, and disease was ever-present. On the snow-covered wharf in eastern Wisconsin, survival more than enjoyment of liberty, equality, and champagne-filled springs was the main concern.Footnote 9 “No money and could not speak [the language] and no countrymen: Father sick unto death – and so my youngest sister and youngest Brother. This was a landing, opposite the gloriously golden and happy anticipation when leaving,” remembered Rasmussen.Footnote 10 But an older Danish sailor, in the United States known as Johnson, “solicited help and finally by evening got us carted off into town and sheltered in a small, poorly furnished tavern or restaurant, kept by a young German and his wife,” recounted Rasmussen.Footnote 11

At the German couple’s place, the family regained their strength somewhat. With the help of fellow Scandinavian immigrants, they – after a brief stay at the local poor house – slowly regained their collective footing. Their fourteen-year-old son Fritz was sent away to work for a newly arrived Norwegian shoemaker, and shortly thereafter a sizable group of approximately fifty Danish immigrants, inspired by Rasmus Sörensen’s emigration pamphlets and Claus Clausen’s letters, arrived.Footnote 12 By June 1848, the newcomers had established a settlement, which was later named New Denmark.Footnote 13

For six years, Fritz Rasmussen worked odd jobs in Wisconsin away from the small immigrant town, but in 1854 he returned, bought land, and soon started to keep meticulous records of major and minor events in New Denmark – not least land transactions.Footnote 14 In his thousands of surviving diary pages, Rasmussen on several occasions mentioned his acquisition of Section 24, N.E. ¼, S.E. ¼ in New Denmark, and the pride thus exhibited in landownership was in no small part tied to his family’s Old World experience.Footnote 15

Looking back later in life, Fritz Rasmussen reflected on his experiences in New Denmark in contrast to the Old World despite the hardship also encountered in Wisconsin: “We have come to this Country, where we are as free, previledged [sic] and no distinction – as to ‘Liberty and Equality’ of person – as the Nobles – so called – are in the lands where we came from.”Footnote 16

This idea – Old World nobility whose disproportional political power and landownership “restrained” the hard-working, honest, common man from achieving liberty and establishing his “pedigree” – defined Fritz Rasmussen’s worldview and, as we have seen, recurred regularly among early Northern European laborers.Footnote 17 While Rasmussen, consciously or unconsciously, benefited from his skin color and religion in terms of landownership and employment opportunities, his views on New World citizenship were not unlike those of the German forty-eighters, who, as Allison Efford Clark has shown, proposed “a nationalism based on residence, not race or even culture, and a form of citizenship grounded in universal manhood suffrage.”Footnote 18

Still, this ability to enjoy the fruits of one’s own labor, earning one’s own bread through one’s own sweat, was a key pull factor to Scandinavian immigrants and one made possible, in part, by whiteness.Footnote 19 When Catharina Jonsdatter Rüd, a Swedish immigrant maid making $2 a week and living in Moline, Illinois, wrote home in March 1856, she celebrated America and the individual liberty she experienced as a white woman:

Here the servant can come and go as it pleases her, because every white person is free and if a servant gets a hard employer then she can quit whenever she likes and even keep her salary for the period she has worked … A woman’s situation is as you can imagine much easier here than in Sweden and I Catherine feel much calmer, happier and more satisfied here than I used to do when I attended school in Nässjö. Everything in this country [seems praiseworthy] – to describe all benefits would take a lifetime!Footnote 20

Rüd underlined the word “white” and thereby proved herself aware, as Jon Gjerde has pointed out, that she enjoyed “freedoms that did not exist in Sweden or for nonwhite people in the United States.”Footnote 21 Since enslaved people in the United States were denied the fruits of their labor, Scandinavian-born laborers generally opposed slavery, with its parallels to the forced labor and serfdom which had been common in Denmark and Norway up until 1788. Unequal power and labor dynamics continued to exist in various guises in Scandinavia subsequently, and the Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants therefore arrived in the United States with suspicion of slavery’s extension or its beneficiaries’ political powers in the New World.

Thus, by the mid-1850s, the Republican Party’s ideology, what Eric Foner has termed free soil, free labor, and free men, meaning wage earners’ opportunity to become “free men” through landownership, aptly described a large swath of Scandinavian immigrants’ economic and social priorities and, by extension, their attraction to the Republican Party in the years surrounding the Civil War.Footnote 22

The issue of free soil was of central concern to Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes in the Midwest. With its importance for economic uplift and perceptions of liberty, land availability, in areas where slavery did not impact labor relations, played a significant part in shaping economic, legal, and moral positions in the Scandinavian-American immigrant community.

Yet, well-read Scandinavian immigrants such as Even Heg and his fellow early editors of Nordlyset, who had advocated legislation to prevent slavery from spreading into the territories between 1848 and 1850, in line with the Free Soil party’s platform, rarely extended their argument to advocate for nonwhite people.Footnote 23 In this regard, Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes were far from alone. As Henry Nash Smith observed more than sixty years ago, “the farmers of the Northwest were not as a group pro-Negro. Free-soil for them meant keeping Negroes, whether slave or free, out of the territories altogether. It did not imply a humanitarian regard for the oppressed black man.”Footnote 24

Smith might as well have added lack of humanitarian regard for American Indians. In their dismissal of Native peoples’ rights, Scandinavian immigrants, not least the better educated ethnic elite, differed from the central actors of the abolitionist movement who explicitly connected Indian dispossession to slavery’s extension.Footnote 25 In short, Scandinavian immigrants, over time, showed themselves to be passionate Republicans but not abolitionists.

During the late 1840s and early 1850s, with the Democratic Party, the Free Soil Party, and the Whigs all vying for the Scandinavian vote, it was not evident that these newly arrived immigrants would eventually side with what became the Republican Party’s platform, but it was clear that the majority of Scandinavians were primarily interested in free land and less in nonwhite free men despite their professed love of liberty and equality.Footnote 26

Despite his Old World abolitionist inspiration, Claus Clausen in 1852 attempted to find a golden mean politically as the first editor of Emigranten.Footnote 27 Clausen saw Emigranten’s mission in the New World as mobilizing its Scandinavian readership politically, not least in support of liberty and economic opportunity, and in the process he loosely aligned the newspaper with the Democratic Party while relegating discussions of nonwhite people in America to the margins.Footnote 28

In an opening editorial, written both in English and Danish, Clausen stressed the importance of embracing assimilation, which underlined the advantages enjoyed by the paper’s mainly Protestant, literate, and white readership who were generally shielded from nativist critique.

We sincerely believe that the truest interest of our people in this Country is, to become AMERICANIZED – if we may use that word – in language and customs, as soon as possible and be one people with the Americans. In this way alone can they fulfill their destination, and contribute their part to the final development of the character of this great nation.Footnote 29

This openness (and ability) to Americanize, based on both individual and broader public interest, made Scandinavian immigrants more politically acceptable to Yankee Americans otherwise attracted to nativist ideas well into the 1850s and slowly provided political prospects for Scandinavian candidates as well.Footnote 30 Emphasizing the political rights and opportunities associated with American citizenship, Clausen, in an editorial dated February 13, 1852, underlined the importance of “schools, churches, and other civilizing influences” necessary for achieving political influence in America and warned his readership against wandering “out into the wilderness as soon as the land is acquired from the Indians.”Footnote 31 Focusing solely on land development might lead to missed political opportunities, Clausen warned.Footnote 32

During the presidential election campaign of 1852, Emigranten, under the editorship of Clausen’s successor, Charles M. Reese, explicitly supported the Democratic candidate Franklin Pierce at the national level but encouraged the paper’s readership to support Scandinavian candidates in local elections for the state legislature regardless of political party.Footnote 33

One such candidate was Hans Heg, the twenty-two-year-old son of Even Heg. Hans Heg ran for the Wisconsin State legislature on a Free Soil platform out of Racine in 1852 but – partly due to the fact that Scandinavian immigrants still made up less than 10 percent of Wisconsin’s foreign-born population in 1850 – lost narrowly to a Democratic candidate.Footnote 34

Yet, as the Whig and Free Soil Party morphed into the new Republican Party in the wake of the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act, the new political alliance, based on a strong commitment to free labor ideology, free soil, and, in time, a strong anti-slavery platform, increasingly appealed to Scandinavian immigrants.Footnote 35 By November 3, 1854, Emigranten, now edited by Norwegian-born Knud J. Fleischer, stated the paper’s position as being firmly in support of the Republican Party:Footnote 36

The November 7 election day is upon us!

Then it will become apparent if wrong shall conquer right, good conquer evil, if slavery shall be expanded and supported, liberty suppressed and curtailed! The Republican Party fighting for liberty and right has risen up to fight the “Democratic” Party’s friends, the defenders of slavery. Norsemen, you would not [want] the advance of slavery!Footnote 37

Emigranten conveniently ignored any lingering Republican nativist sentiment left over from the locally successful Know-Nothing party in the 1854 elections and tried to shift readers’ focus.Footnote 38 By the summer of 1855, Fleischer was urging “Norwegians to work for the Republican platform,” as in his opinion there “prevailed a vicious alliance of antiforeign Know-Nothing enthusiasts and unrighteous ‘slavocrats’” in the Democratic Party’s ranks.Footnote 39

Thus, Emigranten, which had for its first two years maintained an affiliation with the Democratic Party, as evidenced by Reese’s endorsement of Pierce in the 1852 election, adjusted its position based on the debate over free soil and, by extension, nonwhite free men, in part due to the impact slavery had on labor relations. From 1855, with the Republican Party gaining strength on the ground in Wisconsin, Emigranten aligned itself clearly with the anti-slavery party and urged Scandinavian immigrants to do the same.Footnote 40

By 1855, even openly Democratic newspapers such as Den Norske Amerikaner (The Norwegian American) made anti-slavery arguments. Den Norske Amerikaner pointed out that slavery had been “the main theme” in American politics since 1850, and in a front-page piece titled “Negerslaveriet og fremtiden” (“Negro Slavery and the Future”) the editor argued that the conflict between slavery and freedom had the potential to break the United States into pieces.Footnote 41 Expansion of slavery into the territories, it was argued, “would paralyze all political power in the northern states and make them a sort of commercial appendix to the all-commanding slave oligarchy” where free labor was subjugated in relation to “a profitable and advantegous monopoly.”Footnote 42 Perhaps worst of all, slavery’s sinfulness was being ignored in the South, and when Northerners pointed this out, “they point to their slaveholding clergy and slaveholding churches, with their prayers, awakenings, and the entire mechanism of a hypocritical religion.”Footnote 43

Starting with the Republican Party’s grassroots organizational activity in 1854 and supported by amplified anti-slavery advocacy in the Scandinavian press in 1855, the Scandinavian immigrant community became increasingly aware of slavery’s economic and moral implications on life in America. If the future United States could only be built on free soil, free labor, and free (but not necessarily equal) men, then Scandinavian-born agricultural laborers were willing to support the Republican Party’s political project in ever-increasing numbers.

When the Republican Party’s foot soldiers started to fan out over the Midwest to influence local, state, and national elections, they also helped shape opinions in Scandinavian immigrant enclaves. Andrew Fredrickson in 1861 remembered the middle of the 1850s as a politically formative period, where “the Republican Party, of which I am part,” was created.Footnote 44 Also, Celius Christiansen in his memoirs specifically remembered an 1854 visit to New Denmark by a representative of the Republican Party which he – along with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s bestselling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and a bribe of two dollars to vote for De Pere as Brown County’s county seat – credited with cementing his anti-slavery views in support of the Republican Party.Footnote 45

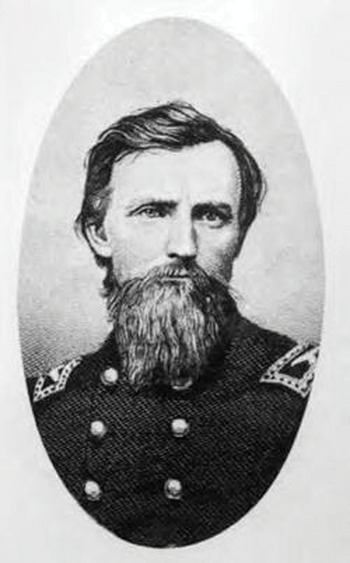

With the help of Norwegian leaders such as Hans Heg (see Figure 4.2), Emigranten’s agenda-setting ability on behalf of the Republican Party, and the canvassing and bribery experienced by immigrants such as Celius Christiansen, Scandinavian immigrants were slowly but surely primed through political campaigns and editorials to support the Republican Party.Footnote 46 On July 11, 1856, Scandinavian anti-slavery sentiment was concretely tied to support for the Republican Party when a broadside from the Republican state central committee was distributed by Emigranten in Norwegian. “The Union’s current political battle is the conflict between liberty and serfdom,” read the proclamation’s first paragraph, in language that closely mirrored the phrases used by Scandinavian immigrants themselves.Footnote 47

The Central Committee’s plea for Republican presidential candidate John C. Fremont went on to emphasize the fact that it was not trying to influence “the Scandinavians or other adopted citizens to do anything other than what any good and informed Christian would recognize as right” and additionally distanced the party from the “despised Know-Nothingers.” In conclusion, the Republican committee added, “everyone who in his heart hates slavery will vote for Fremont.”Footnote 48 In other words, any anti-slavery, pro-free labor, enlightened Christian immigrant could safely support the Republican Party going into the 1856 election.

The link between religion and anti-slavery sentiment was an important one. The abolitionist movement had long and deep ties to religious factions, such as the Quakers and Puritans, arguing, as did Grundtvig and Claus Clausen among others, for a common humanity.Footnote 49 On June 10, 1857, Nordstjernen (The North Star), a newly established “National Democratic Paper” within the Scandinavian-American public sphere explicitly linked free soil, popular sovereignty, and religion in its opening editorial but implicitly admitted the difficulty of defending “popular sovereignty” and the resulting violence in western territories to a Scandinavian audience.Footnote 50 While admitting that bands of bandits, who “happened to vote the Democratic ticket,” had crossed into Kansas and committed violent acts against settlers, Nordstjernen’s editor attempted to shift the responsibility to abolitionist agitators.

Who was it that eagerly seized this opportunity for political gain? Who collected money, arms, ammunition and people to send to Kansas and keep up the Civil War? The “Republicans”! … Men like Horace Greeley, Henry Ward Beecher and thousands of others of the same mold, who overtly preached insurrection through the press and from the pulpit.Footnote 51

Beecher’s importance in the anti-slavery struggle was not lost on Scandinavians residing in or visiting the New York area. As early as 1850, Fredrika Bremer heard Beecher preach on his opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act and described the chapel as “full to overflowing.” He is “much esteemed and beloved,” as well as “highly gifted,” noted Bremer.Footnote 52

Since 1847, Henry Ward Beecher had placed his Brooklyn-based Plymouth Church on the national map with his fight against slavery and, according to at least one study, used the church as a hub for the Underground Railroad and a stage for anti-slavery events (see Figure 4.3).Footnote 53 Among the several Scandinavian immigrants who regularly attended Beecher’s sermons was Danish-born Ferdinand Winslöw, who on December 14, 1856, braved heavy rain en route to Plymouth Church to witness what he would describe to a Midwestern audience the following day as “Henry Ward Beechers Prædikener Om Negerne i Amerika” (Henry Ward Beecher’s Sermons on the Negros in America).Footnote 54

Figure 4.3 Henry Ward Beecher, here photographed with his famous sister Harriet after the Civil War, made a strong impression on Scandinavian congregationists and visitors to Plymouth Church.

However, when Winslöw published his Beecher-based musings in the pages of Kirkelig Maanedstidende (Church Monthly) in March 1857, the powerful, conservative, well-educated Scandinavian clergy was in the process of distancing itself from revivalist interpretations of Lutheranism and aligning itself more closely with pro-slavery interpretations of the Bible.

Claus Clausen had started Kirkelig Maanedstidende together with his Norwegian-born colleagues Adolph Carl Preus and Hans Andreas Stub in 1851, but few members of the Scandinavian religious elite held positions as close to abolitionism as him. Consequently, collaboration on religious matters was not frictionless.Footnote 55

The Norwegian synod’s clergymen, many of whom were closely affiliated with the Norwegian state church, underscored their theological conservatism when they conducted a Midwestern search to establish collaboration with a larger Lutheran synod for future Scandinavian clergymen’s education. To achieve this goal, two pastors appointed by a synod committee to study theological seminars between 1852 and 1857 settled for an affiliation with the German-led Concordia College in the slave state Missouri, instead of Buffalo or Columbus in the north.Footnote 56

Given the Norwegian synod’s decision to establish a partnership with the conservative German Missouri Synod, where an August 1856 article in the church’s periodical Lehre und Wehre (Teaching and Guidance) “concluded that slavery and Christianity were not in any way incompatible,” it may seem surprising that Winslöw’s depiction of Beecher’s anti-slavery sermons were published in the official outlet for the Norwegian Synod in 1857.Footnote 57

Winslöw’s timing is part of the answer. Anti-slavery contributions stopped appearing in Kirkelig Maanedstidende after the first Norwegian students left for Concordia College in St. Louis in the summer of 1858. Yet, outside the Norwegian Synod, the revivalism and anti-slavery of Henry Ward Beecher clearly inspired Scandinavians like Winslöw who felt compelled to disseminate the Plymouth Church preacher’s ideas about slavery and sin, which seemed closer in spirit to the Scandinavian revivalist factions than the Scandinavian state churches, to a wider Scandinavian audience in the Midwest.

“One of the most brilliant personalities in this country is undoubtedly Henry Ward Beecher, admired by his friends, hated and slandered by his enemies,” Winslöw wrote. To the Danish immigrant, Beecher was “the forceful giant of truth in these times of confusion.”Footnote 58

Yet, one of the “truths” that Beecher promoted was the idea of a social hierarchy based on typologies of race. The distance between Lorenz Oken’s “five races of man” – or Carl Linneaus’ Systema Naturae with Europeans on top of a racial hierarchy – and Beecher’s sermon this Sunday was negligible.Footnote 59 In Beecher’s sermon one found the savage yet noble Indian, too “proud to be subdued to Slavery,” fleeing before civilization but destined for destruction, as well as the unattractive, uneducated slave who needed white Anglo-Saxon Protestant help to attain social uplift. The substance of Beecher’s sermon was significant because of the influence the preacher had on American religious culture and, by extension, the countless congregationists attending and disseminating his sermons.Footnote 60

While Beecher emphasized that “African people are not stupid,” that “for music, oratory, gentility, for physical learning and the fine arts, they have a genius just as truly as we have not,” and that colonization was a hypocritical pipedream, it was clear that the Plymouth Church preacher did not consider African-Americans his equals. “We are the great Anglo-Saxon people,” said Beecher. “We boast that the African was brought here from his own wretched home to learn the truths that are brought to light in the Bible, but when he is here we pass laws forbidding him to learn to read it.” He added:

The whole nation is guilty. But the thing cannot go on; either Slavery will kill out Christianity, or Christianity will abolish Slavery … Emancipation is only a question of time, not of fact. Society must lift up these dregs, or they will eat out the bottom and all fall through … Society can’t carry our Slavery in its bosom. Slaves, without culture, will rock down our civilization – with culture they will free themselves.Footnote 61

The means to cultural uplift was education, according to Beecher, and toward the end of the service a collection was made to benefit a school for young Black women. Among the school’s original benefactors was Henry Ward Beecher’s older sister Harriet, the famed abolitionist author.Footnote 62 Yet Beecher’s view of “Africa among us” clearly demonstrated the limits of abolitionist sentiment, even among individuals who were considered central to, or at least active in, the movement. As such, Beecher’s sermon reflected Stephen Kantrowitz’s point that “open advocacy of interracial sociability as a means of improving society was rare even among committed white abolitionists.”Footnote 63

Nonetheless, Beecher’s notion of the thrifty, beautiful European immigrants and Anglo-Saxon Americans, who, despite their original sin, could get ahead in society if they worked hard and played by the rules, appealed to Scandinavian immigrants like Winslöw and his Scandinavian social circle. Winslöw’s older brother, Wilhelm, later recalled:

In the beginning of 1857 my younger brother Ferdinand invited me to come and stay with him in the United States. A year and a half was spent on that visit, which proved of great importance to me in more than one respect. I shall here only mention that I became highly influenced by the preaching and theological views of Henry Ward Beecher.Footnote 64

Furthermore, Ferdinand Winslöw’s brother-in-law, Christian Thomsen Christensen, practiced what Beecher preached in the aftermath of the 1856 sermon. Christensen and his family joined Plymouth Church in July 1857, and, though they temporarily “dissolved” their connection in December 1857, they renewed their membership and played a prominent part in the church after the Civil War.Footnote 65 Other people in the Scandinavian network listened to Beecher’s sermons, as evidenced by the church’s prominence in several travelogues from America before and after the Civil War.Footnote 66

The Scandinavian connection to Beecher’s revivalist church and the connection between his anti-slavery views based on white Protestant superiority were important because Winslöw worked consciously to establish a link between Beecher’s ideas and the Scandinavian Midwestern communities by disseminating the December 1856 sermon to Kirkelig Maanedstidende’s readers.

In Beecher’s sermons, religion intersected with politics. Henry Ward Beecher’s brand of Protestantism, known as “the gospel of love” or “the gospel of success,” focused on individual agency (e.g. “his belief that anyone could become successful if only he worked at it”), while maintaining some belief in “original sin,” and his humorous, populist preaching style – what Mark Twain later termed the ability to discharge “rockets of poetry” and explode “mines of eloquence” – attracted thousands every Sunday.Footnote 67

Importantly, Beecher’s views on slavery and social mobility and his notions of white superiority to some extent inspired and closely mirrored well-educated Scandinavian immigrants’ thinking, helping undergird their “free soil” opposition to slavery as well as their rationale for participation in American territorial expansion.Footnote 68 Moreover, Beecher’s gospel of success served as an argument for free labor ideology – the call for Christianity to abolish slavery was an argument in support of “free men” – yet a notion of white, Protestant superiority held the sermon’s two strands together.

This was part of the reason Winslöw described Beecher as “a giant of truth,” excitedly relaying his sermon, and it was part of the reason Beecher continued to inspire. Beecher helped legitimize Scandinavian immigrants’ rationale for claiming and owning land in the Midwest and their attempt to achieve upward social mobility through hard work in a free labor economy. Moreover, due to the constant influx of immigrants from the East Coast to Scandinavian settlements in the Midwest, as well as the fact that Norwegian immigrants had travelled from Muskego, Wisconsin, to New York as early as 1852 to help their newly arrived countrymen, Winslöw and his brother-in-law Christian Thomsen Christensen were well-known in the larger Scandinavian settlements out west.Footnote 69 Claus Clausen, for example, later in life described both Christensen and Winslöw as friends, and vice versa.Footnote 70

Whether it was in Beecher’s church in Brooklyn or in more primitive Midwestern places of worship, numerous early Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants availed themselves of this opportunity to explore religion outside the Scandinavian state churches. As we have seen, the early Norwegian immigrants of Muskego, Wisconsin, transplanted parts of the Haugean movement to American soil; the early Swedish settlement in New Sweden, Iowa, converted to Methodism; and importantly a large proportion of Danish immigrants to the United States who did not settle in the Midwest came on tickets paid by the Mormon Church en route to Utah.Footnote 71

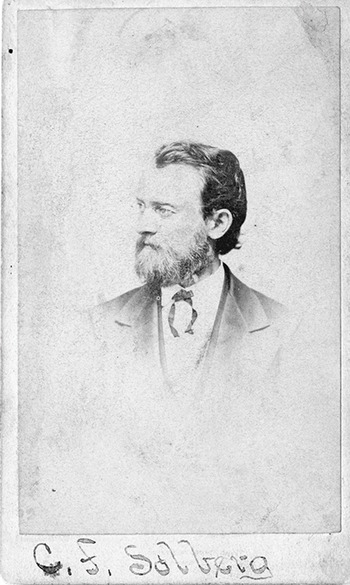

Claus Clausen also increasingly linked religion and anti-slavery agitation in the more secular public sphere and initially found an ideological ally in Norwegian-born Carl Fredrik Solberg, who took over Emigranten on April 17, 1857 (see Figure 4.4).Footnote 72 Solberg gladly carried on the paper’s position on “the slavery and public land issues,” which had been in place since Fleischer’s editorship.Footnote 73

Almost simultaneously with Emigranten’s editorial change, prominent Scandinavian-born men founded the Scandinavian Democratic Press Association and a few months later launched “a National Democratic” competitor to Emigranten.Footnote 74 Nordstjernen (The North Star), which succeeded Den Norske Amerikaner, published its first issue on June 10, 1857, but quickly ran into trouble based on its position regarding slavery.Footnote 75 Before 1854, the Democratic Party’s insistence on individual freedom and support of immigrant causes seemed to hold some sway over a Scandinavian audience averse to interference from the government or clergy based on their Old World experience, but increasingly the question of slavery, exacerbated by Democratic leader Stephen Douglas’ advocacy of “popular sovereignty” in Kansas, proved difficult for Democratic newspaper editors to defend. The issue of free soil, with its underlying premise that American Indians had no right to the land, was an issue of utmost importance for Scandinavian immigrants: in tying discussions of free soil to discussions of free men, not least the moral issue of free non-white men, Emigranten gained an upper hand in the competition.Footnote 76

Not even Charles M. Reese, a skillful writer and editor who “was not without a following” and who found employment with Democratic newspapers after his departure from Emigranten, could gloss over the increasing political differences on the issue of slavery, and the Scandinavian editors’ position on human bondage proved to be the key to the success, or lack thereof, of Nordstjernen in competition with Emigranten.Footnote 77

When Solberg recounted the competition between the two papers later in life, he noted that Nordstjernen failed “to make much headway among the Norwegians” and emphasized the Republican Party’s increasing appeal to immigrants advocating free soil and anti-slavery politics.Footnote 78

When the Emigranten plant was moved to Madison I was made editor of the paper, and when the new Norwegian paper [Nordstjernen] was started I became at once one of the targets of its abuse. We had it hot back and forth, but I felt that I had the better of it as our paper was on the right side of public questions.Footnote 79

While it is difficult to determine the exact ideological leanings in Scandinavian communities at the ground level, subscription numbers and scattered diary references indicate that Emigranten, as a loyal supporter of the Republican Party, was far more attractive than Nordstjernen. By early 1854, Emigranten’s self-proclaimed subscription list counted between 500 and 600 names, and its overall readership, due to newspapers being shared in the settlements, was likely higher.Footnote 80 In contrast, no issues of Nordlyset were published between October and December of 1857, and in subsequent editions complaints over the newspaper’s financial state appeared regularly, while Emigraten’s weekly issues arrived steadily in Scandinavian enclaves and helped build a Scandinavian Republican electorate during the same time span.Footnote 81

In addition to the issue of free soil, Reese and Solberg sparred over the issue of Black people’s ability to vote in Wisconsin when the question was debated in the summer and fall of 1857. On November 3, 1857, a referendum was held in Wisconsin on the issue of “Suffrage for African Americans,” meaning African-American men over twenty-one years of age, and Solberg’s editorials in the weeks and months leading up to the election argued for Black people’s right to vote while also explicitly stating that Emigranten’s editors distinguished between the Republican Party’s policy and abolitionist policy.Footnote 82

According to the editor, it was Emigranten’s position that everyone should “be free and have equal rights.” The Scandinavian newspaper opposed slavery’s expansion but would not interfere with slavery where it already existed. “Abolitionists we have never been,” the editor stated. Yet, “when a free Negro settles in Wisconsin, he should enjoy his share of civil rights.”Footnote 83

Conversely, Reese warned Nordstjernen’s readers that the result would be “a black governor and a black legislature in Wisconsin! … Would not our Black Republican friends then rejoice? Then there would be not freedom and equality, but first the Negro and after him the white man.”Footnote 84

While Solberg likely was ahead of the Scandinavian public opinion on this issue – and also later changed his editorial stance – Solberg’s editorship does indicate the increased focus on anti-slavery issues within the Republican Party. Moreover, the Scandinavian electorate in Wisconsin seemed to be increasingly following Solberg’s arguments.Footnote 85

Thus, when Solberg later in life remembered that he got the better of Nordstjernen, it had much to do with the Republican Party’s appeal to Scandinavians based on free soil and free labor policies.Footnote 86 In a September 12, 1859, profile of Hans Heg, likely written by Solberg, the Norwegian-born politician’s successful rise from farmer to businessman and candidate for statewide office with broad-based ethnic support was emphasized along with his long-standing “opposition to the spread of slavery.”Footnote 87

Thus, Abraham Lincoln’s speeches in Cincinnati and Milwaukee in September 1859, building on his argument for the primacy of free labor stretching back to the mid-1840s, likely resonated powerfully in the Scandinavian-American community. Social mobility, what Abraham Lincoln on September 17, 1859, called, “improvement in condition” in a free country, was “the great principle for which the government was really formed.”Footnote 88

A few weeks later, at the Wisconsin State Fair in Milwaukee, Lincoln elaborating on these free labor thoughts. “Men, with their families – wives, sons and daughters – work for themselves, on their farms in their houses and in their shops,” he said, “taking the whole product to themselves, and asking no favors of capital on the one hand, nor of hirelings or slaves on the other.”Footnote 89 Free labor, Lincoln argued, led workers to reap “the fruit of labor” and thereby gain the opportunity for economic improvement.Footnote 90 On July 2, 1860, in one of the few editorials in Emigranten signed directly by Solberg himself, he clearly laid out his and his newspaper’s reasons for supporting Abraham Lincoln in the important upcoming presidential election. The Democratic Party’s political decay and despotism, after decades in power, played a part, but anti-slavery attitudes, pro-homestead sentiment, and opposition to non-contigious empire were issues at the top of the list.

“Emigranten” will work actively in this electoral campaign and be in “the thicket of the fight” for Lincoln and Hamlin, for the freeing the territories, for the Homestead Bill’s adoption, for the Cuba Bill’s rejection, for a moderate toll’s adoption to protect interests in the northern and western states etc.Footnote 91

For a few months, Solberg even lowered Emigranten’s subscription price to 50 cents annually compared to $2 during the previous presidential election campaign and thereby indicated the importance he placed on influencing Scandinavian popular opinion in the coming months.Footnote 92 The ties between Emigranten and anti-slavery advocacy was made even clearer in August 1860, when Solberg’s good friend, Hans Heg, serving as prison commissioner, decided to shield abolitionist editor Sherman Booth from arrest by the authorities at the Wisconsin State Prison.Footnote 93

Booth had gained national fame in March 1854 when he gathered a crowd to free runaway slave Joshua Glover in Racine and afterward became a prominent voice in the anti-slavery struggle.Footnote 94 “We send greetings to the free states of the Union, that, in the state of Wisconsin, the fugitive slave Law is repealed!” Booth wrote in his newspaper the Milwaukee Free Democrat.Footnote 95 Yet, in a prolonged back-and-forth legal toggle, Booth was by March 7, 1859, unanimously found guilty of violating the Fugitive Slave Act by the United States Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney.Footnote 96

Accordingly, federal authorities arrested Booth on March 1, 1860 and placed him in the federal custom house in Milwaukee. Booth remained confined in Milwaukee until August 1, when ten of his political allies broke him free and ushered him to the state penitentiary in Waupun, where he received lodging under Heg’s supervision.

On August 2, 1860, a US marshal arrived at the Waupun prison looking to apprehend Booth, with a letter from a federal marshal, John H. Lewis, asking Heg to assist in Booth’s arrest. The Norwegian-born prison commissioner, however, replied that his men “currently were employed in a better and more honorable way.”Footnote 97 By August 3, Heg instead invited Marshal Garlick in to arrest Booth in person, but Booth threatened to shoot anyone who tried to arrest him.Footnote 98 When later deposed, witnesses remembered Garlick saying, “The men that talk so much about shooting are not the ones to shoot.”Footnote 99 When Garlick, however, asked Heg what he thought about the situation, he received the following answer:

Mr. H. replied that he did not know what Booth would do, but if he was in Booth’s place and had been houn[d]ed round for the last six years, the very first man that should make an attempt to arrest me I would shoot him down as I would a dog. Mr. Garlick asked H. if he had anything against him as a man. Heg replied I have nothing against you Garlick as a man, but I think you ought to be in better business than serving as the tool for the slave catchers.Footnote 100

Heg’s remarks, and Booth’s threat of violence, made the federal marshal leave the prison; with the aid of abolitionist allies, Booth continued to escape federal agents for two more months before he was finally arrested in Berlin, Wisconsin, on October 8, 1860. Because of Heg’s role in what turned out to be Booth’s initial escape, the Scandinavian prison commissioner, who held larger political aspirations, was afforded considerable statewide attention, as he relayed his version of events in English-language and Norwegian-language newspapers.Footnote 101

To Scandinavian readers, at least the way it was remembered, the episode added to Heg’s anti-slavery credentials and solidified his position as a Scandinavian political leader. The event was important to Emigranten, and likely to its readers, because it was a Norwegian-born immigrant taking an overt stand against the Fugitive Slave Act, and in that context it mattered less that Booth’s personal popularity in the pages of Emigranten was negligible due to his sexual assault of a fourteen-year-old girl the year before.Footnote 102

Emigranten’s increasingly firm anti-slavery position seemingly resonated with Scandinavian newspaper readers to a much greater extent than was the case with the rival Nordstjernen. Between 1858 and September 1860, Nordstjernen was edited by the politically ambitious Danish-born immigrant Hans Borchsenius, but it failed to find an effective counter to Emigranten’s popularity, since the Democratic Party seemed increasingly pro-slavery from the Scandinavian readers’ perspective.Footnote 103 When Borchsenius was nominated by the Democratic Party on September 19, 1860, to run for county clerk, he passed the editorial duties over to his employee Jacob Seeman. In his first editorial on October 10, Seeman drew upon the Democratic Party’s long history and central position in American politics as an appeal to Scandinavian readers. Seeman simultaneously expressed pride in and support for the threshold principle’s main strands of population growth and territorial expansion, which likely had a broad appeal among a Scandinavian readership.

I pay tribute to democratic principles and support the Democratic Party because the Union under Democratic rule has grown from 13 to 33 states, has increased its population from close to 4 million to 30 million people and now is regarded one of the mightiest and proudest empires on earth in terms of trade, sea power, agriculture, arts and sciences.Footnote 104

According to Seeman, the Democrats had always been the immigrant’s friend, and it was therefore imperative that the “abolitionizing” Republican Party’s “wrong, deplorable, and treasonous teachings,” were given a more “conservative, honest and truthful quality,” as only the Democratic Party could, or the result could be the deathknell of the Union.Footnote 105 Nevertheless, Seeman’s editorial would prove to be the last ever published in Nordstjernen. Shortly after the October 10 issue, Borchsenius sold the newspaper to Solberg. In a letter to subscribers in January 1861, distributed through Emigraten, the former editor detailed the reasons why and lamented the fact that there was no longer room for “two political papers with opposite views.”Footnote 106

Two years as editor of a Democratic newspaper had disabused Borchsenius of the notion that Scandinavian immigrants, “under the circumstances, due to little interest in reading or more correctly little interest in subscribing to political papers,” were willing to support a newspaper in competition with the Republican Party’s anti-slavery platform. According to Borchsenius, a newspaper needed between 1,500 and 2,000 subscribers to survive, and “the highest number” he had been “able to achieve at ‘Nordstjernen’” had been between 800 and 900, and out of that number there had always “been a few hundred that did not pay.”Footnote 107

Consequently, Borchsenius sold his list of subscribers to Solberg to get out of debt. Emigranten’s subscription list, which, according to Reese, in early 1854 had counted between 500 and 600, had grown sizably under K. J. Fleischer’s and later Solberg’s editorship. When Fleischer handed the editorial reins to Solberg in April 1857, he expressed satisfaction that the subscription list now numbered between 1,300 and 1,400 names.Footnote 108 Moreover, Solberg, in an editorial published on December 7, 1863, put the subscription number at 2,700.Footnote 109 This positive development in subscribers, if the editors’ own numbers can indeed be trusted, corresponds with Theodore Blegen’s assessment. Solberg, according to Blegen, “expanded the paper in size, varied its contents, increased its interest and value as a literary magazine, reached out to all parts of the Northwest for Scandinavian Americans, and built up its circulation until, in Civil War times, it had nearly four thousand subscribers.”Footnote 110

Solberg’s claims that Emigranten’s position was on the “right side of public questions” and therefore decisive in his competition with Nordstjernen found support in the writings of the enterprising Reese, who, by September 22, 1860, now on his fourth newspaper editorship, wrote for a newly established and, as it turned out, short-lived “Republican campaign paper,” Folkebladet,

The struggle this fall will be simply between Freedom and Slavery, and where is the man in the North who can for a moment be undecided as to which side to take? We for one have bid a long farewell to the so-called Democracy and shall hereafter be found battling for Freedom, Free Speech, and Free Territory!Footnote 111

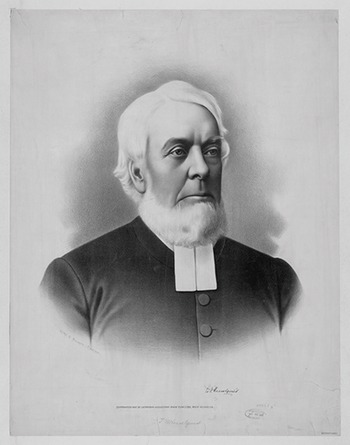

Folkebladet was published out of Chicago, which was also the home of the much more established and influential Swedish-language newspaper Hemlandet. Edited by Swedish-born Pastor Tuve N. Hasselquist (see Figure 4.5), who emigrated in 1852 in part due to his criticism of the Swedish state church, Hemlandet had catered to Illinois’ growing Swedish-born population since 1855.Footnote 112 For years, Hemlandet touted anti-slavery viewpoints to its readership; though it had fewer than 1,000 subscribers, it, according to the estimate of biographer Oscar Fritiof Ander, probably had several thousand readers.Footnote 113

“Perhaps the most effective testimony to Hasselquist’s influence in forming the political opinion of the Swedes is found in the success of Hemlandet over its competitors, Svenska Republikanen and Minnesota Posten,” notes Ander, who adds, “Swedes were Democratic in 1852, but voted Republican in 1856, and since that time they remained so faithful to the principles of that party that all attempts made after 1860 to start at Democratic newspaper were doomed to fail because of lack of support.”Footnote 114

Consequently, the solidly Republican Hemlandet and Emigranten were by 1860 the only surviving secular Scandinavian newspapers in Illinois and Wisconsin, since they were the only ones that could be sustained through Scandinavian-born subscribers.

In trying to explain why Scandinavian immigrants chose so clearly to support the Republican Party, editor Knud Langeland, who by 1867 published the newspaper Skandinaven (The Scandinavian) out of Chicago, offered this explanation: “The Scandinavian people in America joined the Republican party en masse because it was founded upon the eternal truth: ‘Equality before the law for all citizens of the land without regard to religion, place of birth, or color of skin.’”Footnote 115

While this Scandinavian hagiography necessarily needs to be contextualized by their implicit and explicit support for and benefit from their white, Lutheran background, the extent to which Scandinavian immigrants in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Minnesota backed the Republican Party before, during, and after the Civil War is noteworthy.Footnote 116 Thus, the elections of 1860 provided a litmus test for the political power of ethnicity in relation to the Republican platform’s focus on free soil, free labor, and free men among Scandinavian immigrants. The settlement of New Denmark was just one of many examples.

On a beautiful Tuesday morning, November 6, Fritz Rasmussen awoke in New Denmark and observed frost still visible in areas shaded by the trees as he went down to the local schoolhouse to vote.Footnote 117 The Danish immigrant cast his vote for Abraham Lincoln and followed the election proceedings for some time thereafter before returning home to butcher pigs.Footnote 118 Rasmussen thereby took the political advice of Emigranten, but the same was not the case among all New Denmark’s residents. New Denmark, like the rest of the United States, was split in two. The town’s eligible voters gave Stephen Douglas forty-three votes, while Abraham Lincoln received thirty-seven. According to the 1860 census, New Denmark counted 424 inhabitants, including 139 with Scandinavian heritage, while the rest were mainly Irish or German-speaking.Footnote 119 Despite the community’s ethnic differences, everyday life was relatively frictionless, but the presidential election of 1860 revealed political differences tied to Scandinavian immigrants’ notions of ethnicity, the politics of class, and the racially charged notions of citizenship. As such, the election of 1860 foreshadowed future conflict zones surrounding the Scandinavian community.

While immigrants generally had to reside at least two years within the United States to be able to apply for citizenship and vote in elections, Wisconsin’s State Constitution of 1848 specified that “white persons of foreign birth who have declared their intention to become citizens conformably to the laws of the United States” were eligible to vote.Footnote 120 Thus, together with his brother Jens (James), Fritz Rasmussen declared his intention to become a citizen of the United States on March 29, 1860, with the aim of getting a local position of trust in the New Denmark town election in April.Footnote 121 While Rasmussen failed to win local office in April, his declaration of intent made it possible for him to help elect the next president of the United States. As November 1860 drew nearer, New Denmark residents followed political events with increasing interest and, based on Rasmussen’s diary entries, tracked local news closely.Footnote 122

Despite Wisconsin being lauded as the possible birthplace of the Republican Party, Brown County was not a Republican stronghold.Footnote 123 The local newspaper, Green Bay Advocate, was edited by Charles D. Robinson, a Democrat who had served as Wisconsin’s secretary of state between 1852 and 1854; Robinson strongly supported Stephen Douglas in the presidential campaign of 1860.Footnote 124

Leading up to the election, Robinson on a weekly basis lauded Douglas and, on October 19, in an attempt to build up and Democratic groundswell enthusiasm, passionately described a Douglas campaign event in Fond du Lac where he estimated a crowd of 15,000 to be “entirely in bounds.”Footnote 125 Robinson did not report the substance of Douglas’ speech, but, in the week leading up to the election, the editor was much clearer about the fact that slavery was the most important election issue, and he laid out what was at stake to his readership. The Green Bay Advocate urged a vote for Stephen Douglas to ensure that slaves were kept in bondage, as abolition, “if the Republican platform is properly interpreted,” would mean equality for Black people, increased competition in the labor market, and a potential threat to white women.Footnote 126 “To the People of Brown County,” Robinson wrote:

Large numbers of pamphlets in the French and Holland languages, have been put in circulation by Republicans in this county, so utterly untrue in their statements, and so odious in all respects, that it is important something should be said to expose them, although the time is so short before election, and the means of printing in those languages so limited.Footnote 127

Conversely, Emigranten, which also circulated in New Denmark, encouraged support at the ballot box for “freedom and equality,” which, from the editor’s perspective, was personified by Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin.Footnote 128 Thus, to Scandinavian voters in New Denmark, there was a clear choice between Abraham Lincoln (advocated by Emigranten) and Stephen Douglas (supported by the Green Bay Advocate) ahead of the November 6 election.

Since the Democratic Party at its June 1860 convention had split into a Northern (Douglas) and Southern faction (John C. Breckinridge), the Republican Party’s chances seemed promising by November.Footnote 129 Hence, it was a confident Emigranten editor who penned his last editorial on the eve of the electoral contest. Solberg predicted a resounding Republican victory in the North and Midwest and projected Wisconsin to be called for Lincoln at margins even greater than would be the case in Minnesota and Iowa.Footnote 130

Moreover, alluding to the importance of ethnicity in politics, Solberg criticized his countryman James D. Reymert for accepting a Democratic congressional nomination. “In the Second District our sly countryman Reymert has attempted to lead 5,000 Norwegian Lincoln-men astray against their better judgement in a manner that is a poor example to follow,” Emigranten’s editor wrote.Footnote 131 Solberg feared that Reymert’s Norwegian origin could lead Scandinavian voters to abandon Lincoln and the Republicans at the national and state levels in favor of a fellow countryman regardless of his political views. However, Solberg’s fear proved unfounded. In Wisconsin, Abraham Lincoln won a clear victory with a majority of over 20,000 votes, and Scandinavian-born immigrants largely supported the Republican Party.Footnote 132

In New Denmark, for example, Lincoln performed better than in the rest of Brown County, and it is likely that a sizable chunk of the Lincoln vote came from the Scandinavian residents. As we have seen, Fritz and Jens Rasmussen, along with their brother-in-law Celius Christiansen and Andrew Frederickson, supported the Republican Party.Footnote 133 Additionally, New Denmark resident Frederik Hjort was on the list of paying subscribers to the solidly Republican Emigranten.Footnote 134 As such, Hjort, and the neighbors he shared the newspaper with, could read Solberg’s assessment of the election on November 10, where he rejoiced that

Wisconsin has elected all three Republican candidates – Potter, Hanchett and Sloan – for Congress with large majorities. Our friend Reimert, to the credit of the Norwegian part of the population, did not succeed in leading the Norwegian Lincoln-men away from their duty and obtain their votes. Here and there he has received up to half a dozen votes more than his party in a Norwegian township, that is all, and several places he lags behind.Footnote 135

The election returns published by Solberg the following week seemed to validate his point about there being little Scandinavian support for an ethnic Democratic candidate. In the Norwegian townships of Perry, Springdale, and Vermont, which were located in a district won by both James D. Reymert at the congressional level and Douglas at the presidential level, there was no significant ethnic boost in votes, and the same was the case in the Republican-leaning township of Pleasant Springs, where the numbers 119 for Lincoln and seventy-five for Douglas were exactly the same as the numbers for Luther Hanchett and Reymert. All told, Reymert lost by more than 500 votes (4,797–4,210) to the Republican Hanchett in Dane County.Footnote 136

Notably a small handful of Democratic candidates at the local county clerk level – Hans Borchsenius, Ole Heg, and Farmer Risum – all lost also, while John A. Johnsen, a Republican, won in Dane County.Footnote 137 On the topic of slavery’s extension, Scandinavian immigrants likely disagreed with their Irish- and German-born counterparts. As Frederick Luebke has argued, “Lutheran and Catholic Germans in rural areas remained loyal to the Democracy in 1860, while other Protestants and the freethinking liberals were attracted to Republicanism. Irish Catholics were uniformly Democratic despite intraparty problems.”Footnote 138

Lincoln, in the the words of James McPherson, “carried every free state except New Jersey, whose electoral votes he divided with Douglas, and thereby won the election despite garnering slightly less than 40 percent of the popular votes.”Footnote 139 Among the states that decided the 1860 election was Illinois.Footnote 140 On election day in Rockford, Illinois, the Swedish immigrants in town, according to Hemlandet’s correspondent, unanimously gathered in front of the Swedish church and marched to the courthouse while cheering “hurrah” under the American and Swedish flags, “the true Republican ballot making up their only weapon,” and met up with an estimated 100 members of “The Young Men’s Republican Legion” voting for the first time.Footnote 141

According to the letter-writer, every single Swede in town voted Republican and cheered in front of the courthouse, while a group of Irish immigrants left the area, remarking that “had any other nation dared to show up with their national flag it would surely have been torn apart.”Footnote 142 In Red Wing, Minnesota, Swedish-born Hans Mattson remembered leading several meetings in a Republican club before the election and later posited that Scandinavians “almost to a man” were “in favor of liberty to all men” and therefore “joined the Republican party, which had just been organized for the purpose of restricting slavery.”Footnote 143

The Scandinavian vote was not decisive for the outcome of the presidential election of 1860, though ethnic scholars subsequently tried to emphasize its importance. Still, the votes that were cast by Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants did support the Republican Party with seemingly significant margins.Footnote 144

Additionally, in Iowa, ethnically German forty-eighters such as Hans Reimer Claussen and Theodor Olshausen, who had fled Denmark after the First Schleswig War, supported the Republican Party by 1860; in the predominantly Scandinavian township of Cedar in Mitchell County, only 1.4 percent of the inhabitants voted for a Democratic candidate.Footnote 145

In Illinois, Danish-born Ferdinand Winslöw described, on February 12, 1861, going to Springfield with the German-born Republican politician Francis Hoffman to see Lincoln. Here Winslöw was introduced to Lincoln, shook his hand, and listened to the “impressive and tender” farewell address that the newly elected president gave before leaving for the White House.Footnote 146

“I know I cried when the cars started bearing him along with his destiny and that of over thirty millions [sic] men, whose fates he was going to shape,” Winslöw wrote to his wife, adding: “It was a solemn moment for me, but I have an unshaken confidence in his ability, firmness and honesty.”Footnote 147

By February 1861, Lincoln’s ability to shape the country’s fate was already being severely tested. Writing from New York on February 5, 1861, Denmark’s acting consul general, Harald Döllner, assessed the situation in no uncertain terms. “Sir,” Döllner wrote to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, C. C. Hall, “the Union of the states is virtually dissolved.”Footnote 148 South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana had broken away, and delegates were now gathered in Alabama to “form a Southern confederacy.”Footnote 149 One week later, utilizing the language of the threshold principle, Döllner added that “the State of Texas, an empire within itself according to size and resources, has seceded from the Union.”Footnote 150

Two months later, Civil War broke out, and diplomatic tension ran high. In the conflict’s early phase, when the loyalties of several states were still in question, American fear of foreign powers’ interference was palpable. The latent or explicit fear of Kleinstaaterei thus hung over the State Department and left little room for error or compromise, especially in the border states.Footnote 151

In Scandinavian enclaves across the Midwest, the Civil War simultaneously forced Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes to articulate in even clearer terms their understanding of American citizenship. Accordingly, Scandinavian immigrants’ notions of liberty and equality in relation to upward social mobility, their notions of political competition with Irish and German immigrants, and at the highest possible level their notion of universal values in relation to the the Declaration of Independence’s egalitarian ideal were put to the test when civil war broke out on April 12, 1861.Footnote 152