* * *

Following the dawn of the reform era in 1978, when agricultural reform experiments took root in the ashes of the Cultural Revolution, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has undergone an economic and social transformation that is unprecedented in both speed and scale.Footnote 1 Economic growth averaged an astonishing 9.9 percent over three decades. China is now the largest manufacturer in the world, and its economy, having overtaken Japan in 2010, is the second largest after the United States. Chinese citizens have benefitted enormously from this rapid economic expansion. Although China remains a middle-income country, where the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is only about one-fifth of the US level, incomes have risen from an estimated US$225 in 1978 to $7,925 in 2015. In addition, 500 million people have been lifted out of poverty, the urban population has risen from 17.9 percent to 53.7 percent of the total, and the middle class expanded from just 1 percent in the early 1990s to 35 percent in 2008, and could increase to 70 percent by 2020.Footnote 2

Yet, while China’s economy and society have been in a state of constant change, the political system seems all but immutable. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which came to power through war and revolution in 1949, has maintained a firm and continuous monopoly on political power and shows no proclivity toward political liberalization. This perception of suspended political development only deepened during the administration of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao from 2002 to 2012 – a period often characterized as a “lost decade” of reform by observers who point to an expanding security apparatus, the erosion of basic legal protections, and a reversal of earlier electoral and legislative reforms.Footnote 3 Since the Eighteenth Party Congress in November 2012, moreover, China’s new leadership under Xi Jinping has launched a heavy-handed anti-corruption campaign while expanding control over the press, social media, the Internet, academics, lawyers, NGOs, and other groups.Footnote 4

Alongside these authoritarian moves, however, China’s leaders have also implemented far-reaching administrative reforms designed to promote government transparency and increase public participation in official decision-making.Footnote 5 These reforms have included the promulgation of national Open Government Information (OGI) Regulations following local experiments in OGI; initiatives to promote public participation in law-making and administrative rule-making; and integration of citizen satisfaction surveys into criteria used to evaluate the performance of government officials. For example, OGI reforms now grant individuals the right to request information from the government and also instruct government agencies at different levels to disclose information of significant interest to the public – such as information related to government budgets and expenditures. In addition, the central government is expanding public participation through online notice-and-comment at various stages of the policy formation process, and today, all draft laws and regulations appear on the websites of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the State Council, China’s top executive policymaking institution. Online consultation is expanding steadily at the provincial level as well.

In this book, we not only document the evolution and scope of these reforms across China, we also provide a systematic assessment by quantitatively and qualitatively analyzing the impact of participation and transparency on important governance outcomes such as reduced corruption and improved legal compliance and policy effectiveness. Comparing across provinces and over time, we provide evidence that increased transparency is closely associated with lower corruption, while higher rates of participation are effective in enhancing compliance and reducing disputes in the environmental and labor sectors.

We also investigate the motivations behind these reforms and ask a fundamental question: why would the leadership of an authoritarian regime voluntarily compromise its monopoly over information and decision-making? Existing literature does not offer a satisfying answer to this question. Cynics tend to see the reforms as mere “window dressing,” providing a democratic veneer to an otherwise authoritarian system,Footnote 6 whereas optimists view the reforms as conducive to democratization by introducing pluralism into policymaking, raising public expectations for political inclusion, and setting the stage for more accountable governance.Footnote 7 We depart from this simple dichotomy by exploring the possibility that the reforms have led simultaneously to improved governance and more effective one-party rule. While long-term prospects for democratic development remain unclear, we acknowledge that these reforms have increased popular aspirations for transparent and inclusive governance. This is potentially important for China’s long-term political trajectory because democratic development elsewhere has been more stable and long lasting in countries that experienced more open and participatory institutions in pre-democratic periods.Footnote 8

To investigate these issues and study the origins and impacts of the reforms, we divide the main body of our book into two parts. The first has three chapters on transparency, and the second has three chapters on participation. In each part, the first chapter presents the drivers and history of reform; the second provides our quantitative analysis and hypothesis testing; and the third presents case studies. The two parts are bookended by this introductory chapter and a concluding chapter which considers the implications of our research for the future of Chinese governance more generally. The result is a cohesive volume presenting a unique approach to analyzing changes in Chinese governance over nearly two decades.

In the remainder of this chapter, we analyze the theoretical puzzles and questions that inspired our research, examine the historical and political context from which the reforms emerged, and consider how these changes have energized Chinese citizens and raised their expectations about the quality and nature of governance. We also discuss our key research findings. Finally, we examine the trend toward enhanced political control and repression that began during the Hu-Wen period and has accelerated under the Xi Jinping administration since 2012. We return to these themes in our concluding chapter, further exploring the ramifications of the current leadership for the transparency and participation reforms.

1.1. Assessing Chinese Governance

The Chinese Governance Puzzle

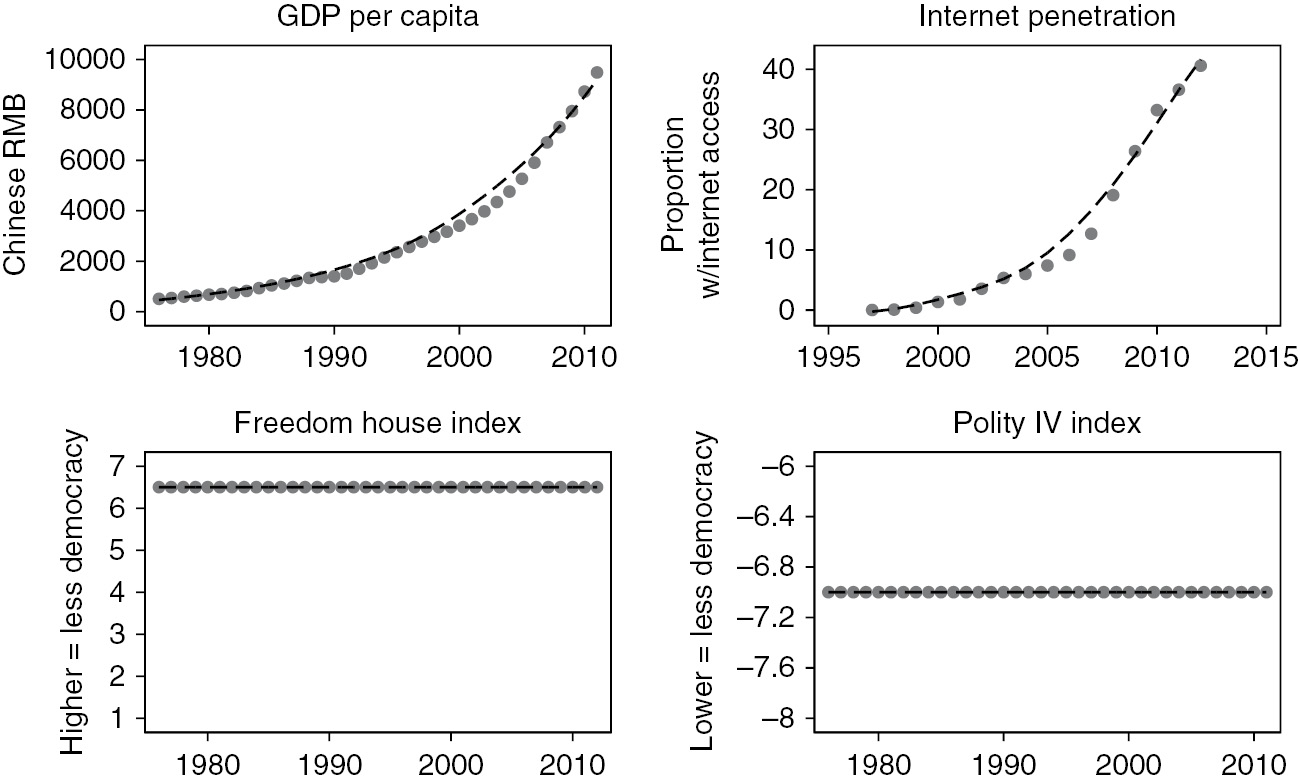

Extensive research in comparative political economy offers persuasive evidence that good governance contributes to economic growth and development.Footnote 9 On almost every dimension, China has demonstrated dramatic and sustained progress in economic development over the past three decades. Yet, despite unprecedented economic growth and modernization, international measures of governance in China have not budged since the 1980s, as depicted in Figure 1.1. Is it possible that governance has played no part in China’s success? Moreover, do we believe that in spite of China’s dramatic socio-economic transformation, politics and government have remained unchanged?

Figure 1.1 The China puzzle

Notes: GDP Per Capita is based on statistics from the World Bank’s Development Indicators. Internet Penetration is calculated from reports published by the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), a Chinese nonprofit. Freedom House and Polity IV scores are calculated from data published by Freedom House and the Polity IV project, respectively.

In 2010, as described in the Preface, we assembled a group of Chinese and American researchers to investigate these questions, with the goal of providing a more nuanced picture of governance reforms and changes in China over time. To better understand the nature and impact of these reforms, we examined two aspects of governance in particular: transparency in the provision of information on government activities, processes, and regulations; and public participation in the formation of government policies. In addition, collection of comprehensive data on both transparency and participation facilitated statistical testing of well-known hypotheses on the relationship between transparency and corruption, on the one hand, and between participation and downstream compliance, on the other. Subsequently, following a mixed methods approach, the project teams carried out case study research in five provinces. Team members conducted interviews and collected primary materials to develop matched comparisons of provinces with diverse conditions and varying levels of participation and transparency. These provincial case studies complement the quantitative analysis by tracing causal mechanisms and accounting for threats to validity in our findings. The case studies also offer colorful examples of how the relationship between reform policies and governance outcomes operates in practice.

While our study aims to assess governance reforms in China based on the goals and aspirations espoused by the Chinese leadership, we acknowledge that we were initially influenced by governance frameworks already established by international development institutions. These organizations define the concept of “governance” in different ways, but in general they focus on the institutional framework of public authority and decision-making. In this context, good governance typically refers to a set of admirable characteristics of how government should be carried out. According to the United Nations Development Program, for instance, good governance is participatory, transparent, accountable, effective, and equitable. It also promotes the rule of law.Footnote 10 During the course of our research, we discovered that Chinese leaders were themselves initiating reforms to improve governance in the realms of transparency and participation – albeit selectively – for their own reasons and instrumental purposes. In other words, these were not just foreign concepts imported for political analysis, but, in a unique way, are also integral to Chinese approaches to governance reform.

Theoretical Foundations – Governance under Authoritarian Regimes

The substantive questions motivating this book are broad and empirical. What is China’s governance strategy? Is it effective? Is it improving? These questions are just as relevant for China as they would be for France, India, or the United States. Yet the theoretical subtext behind the questions, especially given the case that we examine, cuts against conventional thinking on authoritarian regimes, which sees authoritarian rule and good governance as fundamentally incompatible. As Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alistair Smith point out, “When it comes to autocracy, bad behavior is almost always good politics,” not the other way around.Footnote 11

There are several reasons to think that authoritarian regimes are bad at governing. One is that they cater to narrow interests and therefore undersupply public goods.Footnote 12 For instance, an authoritarian government may have fewer incentives to fight crime and protect food supplies because ruling elites reside in gated communities and subsist on imported meats and produce. This may not always be due to neglect; extensive scholarship has shown that most authoritarian regimes collapse following splits between ruling elites. Focusing on narrow interests may thus be an optimal strategy for regime survival.Footnote 13 Another interpretation is that authoritarian institutions are simply ill equipped to deliver good governance. Nearly all autocracies decry government corruption, for example, but still leave officials to police themselves.

Little can be done about the first point. By definition, authoritarianism denotes the concentration of power in a single leader or a narrow elite. There is, however, ample diversity on the second, institutional dimension. Empirically speaking, the differences among authoritarian regimes are just as large as those between autocracies and democracies. Some are despotic and incompetent; others appear bureaucratically efficient and focused on economic growth. Some tolerate opposition parties and hold elections (albeit of dubious quality); others dispense with political competition altogether by institutionalizing one-party rule into their constitutions.Footnote 14

Political analysts tend to conceptualize variation in regime types along a spectrum – with totalitarianism at one end and democracy at the other. Indeed, the literature on comparative authoritarian institutions is filled with typologies that attempt to capture this gradation of nuance.Footnote 15 While our work does not reference such differences per se, dominant themes from this literature have direct bearing on the topic of governance. In particular, economists and political scientists argue that democratic institutions, such as elections and representative legislatures, are conducive to better governance and, by extension, growth.Footnote 16 In short, the closer a regime is to the democratic end of the spectrum, the better the quality of governance should be.

By these metrics, China poses an important puzzle because it is firmly positioned on the authoritarian end of the spectrum. Indeed, the PRC has never elected a national leader to office by popular vote,Footnote 17 nor has the ruling CCP ever tolerated the existence of any fully independent political party other than itself.Footnote 18 Yet since Mao’s death in 1976, China has had no despots (i.e., an individual ruler operating with absolute power and without constraint) and has experienced five peaceful leadership transitions. Organizationally, the CCP leadership resembles an unelected board of directors, embodied in the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC), which governs by consensus, not fiat, as far as we can observe.Footnote 19 In addition, policies emanating from this body have contributed to steadily improved living standards, as discussed above, and more foreign investment flowing into China than into any other economy in the world.

Some of these proclivities can be attributed to purely economic motives. For instance, one could argue that the CCP believes that the best way to enrich itself is by expanding the economy and preventing individual leaders from monopolizing wealth and power. As we document in this book, however, China’s efforts to improve governance extend further and deeper than simple profit maximization. In particular, we show that China’s leaders voluntarily disclose information that could incriminate them. They tolerate public criticism over how they govern and even adjust their plans in response to public input. Such actions arguably make it harder for Chinese governors to focus solely on economic growth, such as when environmental impact assessments thwart industrial development plans. These puzzling administrative reforms motivate our research.

So why, as we posed in the introduction, would an authoritarian regime relinquish its monopoly over information and decision-making? The cynical explanation is that transparency and participation reforms in the absence of competitive democracy are simply ornamental and have little, if any, impact on policymaking.Footnote 20 By contrast, optimists see such reforms as precursors of liberalization and democracy.Footnote 21 While the latter view may eventually prove accurate, it is fundamentally at odds with what many believe an authoritarian regime’s core preference ought to be – namely, to stay in power.

There is a middle ground in this debate. For example, scholars of the late Soviet Union describe early policies for public inclusion not as formalities but as instrumental attempts to mobilize the public into policy implementation – especially on issues where regime capacity was itself limited.Footnote 22 Similarly, China has established an array of “input institutions,” which, according to Andrew Nathan, lead Chinese citizens to “believe that they have some influence on policy decisions” and “that the regime is lawful and should be obeyed.”Footnote 23 By interpreting governance reforms as instrumental, this literature raises the prospect of a resilient authoritarianism whereby regimes negotiate their hold on power not simply by use of force but by delivering more stable and legitimate government.Footnote 24

We share a similar, instrumental view of China’s approach to governance and assume the regime has no intention of giving up its monopoly on power. To this end, any reforms it adopts should, in theory, contribute to its survival. Yet we also consider the possibility that these reforms have tangible effects on governance outcomes that are relevant and of interest to society as a whole, not just to those in power. Specifically, we argue that these reforms in fact deter corruption and improve compliance by engaging citizens in monitoring and decision-making. This instrumental interpretation does not preclude the possibility that administrative reforms could inadvertently facilitate or hasten a transition to democracy. Seen from the regime’s vantage point, however, we consider China’s turn towards transparency and open decision-making not as a stepping stone towards greater democracy but as a response to rampant corruption and weak rule of law – problems that the regime itself admits threaten its survival.

In making these claims, our work draws on well-established theories in the fields of political science, public administration, and even psychology. While we provide a closer examination of this literature in Chapter 2 and Chapter 5, we take the opportunity here to highlight several foundational arguments. In particular, our interpretation of the relationship between transparency and corruption is succinctly captured by McCubbins and Schwartz’s theory of fire alarm monitoring, whereby citizens or media “pull the alarm” when they see wrongdoing.Footnote 25 Similarly, the literature on deliberative democracy views public participation as a source of information that leads to better choices,Footnote 26 and also as a motive for compliance since citizens are more likely to abide by rules that they have had a hand in shaping.Footnote 27

Empirically, evidence shows that transparency and public participation have a positive impact on governance.Footnote 28 In the United States, scholars have linked fiscal transparency to higher levels of legislative effort on the part of politicians.Footnote 29 More broadly, they find that media freedom and greater access to information contributes to more effective and efficient government responsiveness and lower rates of corruption.Footnote 30 With respect to decision-making, scholars find that public participation during policy formulation reduces the risk of administrative litigation once a new policy is adopted.Footnote 31 Others find that deliberation helps to facilitate painful budget cutsFootnote 32 and to increase satisfaction with government spending choices.Footnote 33

Yet these examples tend to come from democratic polities in which administrative reforms are complemented by existing democratic institutions of representation and accountability. While proponents speculate that transparency and participation may achieve similar positive benefits even under nondemocratic institutions,Footnote 34 the evidence is simply insufficient to draw strong conclusions. In this book, we explore the possibility that transparency and participation can have similar effects in nondemocratic environments by testing two core hypotheses in China. Specifically, we investigate whether the following relationships can be observed between the administrative reforms and governance outcomes:

H1: Greater transparency reduces corruption. In keeping with the notion that “sunlight is the best disinfectant,” disclosure of information on government budgets, fees, and discretion standards should reduce opportunities for government corruption by constraining the ability of officials to exploit rules to their benefit.

H2: Greater participation in rule-making enhances downstream compliance. This hypothesis is premised on the logic that when citizens participate in creating policies through notice-and-comment procedures, public hearings, or other participatory mechanisms, they are more likely to believe in the justness of a policy and comply with its stipulations.

We acknowledge, however, that there are reasons to be cautious in testing these hypotheses in authoritarian contexts. Simply put, can transparency and public participation have any effect if citizens are not also granted the power to sanction and express themselves freely? Yes and no. Transparency is unlikely to deter corruption if officials do not believe that exposure of corrupt activities will hurt them. For deterrence to happen, the public must first consume and interpret information provided by the regime’s transparency measures. Second, citizens must speak up when they observe corruption. Finally, since citizens have no means to sanction officials, the state must do so in their stead. If any of these conditions are not met, then transparency is unlikely to have its intended effect. Similarly, public consultation is unlikely to yield any new information if citizens are not interested in participating or if certain groups, especially those who may be critical of a particular policy issue, are excluded from the consultation process. Public consultation is also unlikely to improve policymaking or public perceptions of policy choices if policymakers are unresponsive to the public’s comments and concerns.

Based on this logic, it is easy to see how the governance reforms explored in this book could fail. In particular, if the government cannot credibly signal that public engagement from all parties and critics is welcomed, then these reforms will yield limited informational value. Likewise, if the government cannot credibly signal that it is willing to respond to public input, whether it involves sanctioning corrupt officials or formulating policy initiatives, then these reforms will attract few participants. Put another way, each time the regime silences critics or fails to respond to their feedback and criticisms, then the utility of its governance reforms is fundamentally undermined. We return to this point in the last section of this chapter.

Having outlined the core features of our theoretical framework above, we next turn to a macro-analysis of China’s reform efforts. Specifically, we point to fleeting attempts to reform political and legal institutions as part of a more general effort to improve governance during periods of socio-economic transformation and uncertainty.

1.2. China, the Ambivalent Reformer

When China “opened up” in 1978, its leaders took a huge gamble. They understood that the key to unlocking China’s economic potential was to unleash the market forces and the individual aspirations that the Party had worked so hard to suppress in the past. But the further the Party moved in this direction, the less control it had over its own future. The breakup of agricultural collectives and the ceding of fiscal rights to local governments, for example, meant that citizens and cadre alike were increasingly free to pursue their own interests, often at the expense of the party-state. By the early 1990s, internal surveys suggested that only half of China’s laws were formally enforced.Footnote 35 At the same time, local officials were enacting measures that directly conflicted with the central leadership’s stated objectives.Footnote 36

Cognizant of these challenges, China’s leadership has, on occasion, devoted significant energy to bolstering bottom-up accountability. As early as 1979, China’s leaders paved the way for direct elections for local people’s congresses. By 1983, newly constituted assemblies were meeting and deliberating on policy and, by 1987, direct elections were extended to villages across the country.Footnote 37 In parallel with these electoral reforms, China’s leaders also allocated more resources and authority to the country’s legislative institutions.Footnote 38

In the early 2000s, however, enthusiasm for such institutional reform appears to have waned. In 2001, President Jiang Zemin announced that “villagers’ self-government must not be extended to higher levels.”Footnote 39 Soon thereafter, electoral experimentation was formally forbidden in a nationwide moratorium.Footnote 40 Likewise, progressive reforms in China’s legislature began to stall. In 2002, CCP leaders reasserted party control over provincial legislatures by encouraging local party secretaries to serve concurrently as chairmen in their respective congresses, thereby subsuming the legislative agenda into that of the Party’s.Footnote 41 Later, in 2010, new rules on local deputies redefined the rights and responsibilities of legislative representatives, making it harder for candidates to meet with constituents without the approval of the local election commission and raising procedural barriers to independent candidates.Footnote 42

Yet alongside this reversal in liberal institutional reform, a select set of administrative procedure reforms began to take root, focusing on transparency over government work and on public participation in policymaking. Like institutional and legal reforms, these measures had their origin in the 1980s, when the Chinese regime was struggling to grow out of a planned economy and saw corruption and policy failures as serious threats to its survival. Policymakers began incorporating public consultation measures into decision-making and extended local transparency experiments to the national level. Guangzhou had issued the first local government OGI regulations in 2002, for instance; followed closely by Shanghai in 2004. In time these incremental efforts culminated in the promulgation of national OGI regulations by the State Council in 2008.Footnote 43

As this narrative suggests, official efforts to promote transparency and participation were often propelled by provincial or municipal-level reforms initiated by local authorities. Indeed, China’s broader reform process is replete with examples of local experimentation with pilot reforms that, depending on the political circumstances of the period, would later become national policy. Sometimes, these local experiments were encouraged by the central authorities, but often they emerged more organically and spontaneously in different localities around the country.Footnote 44 In Hunan, for example, the provincial Legislative Affairs Office developed China’s first-ever Administrative Procedure Rule (APR) in 2008 under the leadership of then Governor Zhou Qiang, who later became party secretary of Hunan and is now President of the Supreme People’s Court in Beijing. Patterned on a draft national administrative procedure law that was developed between 2000 and 2003 but later stalled, the Hunan APR encouraged more open government meetings, provided detailed provisions for public hearings and notice-and-comment proceedings, and called on local agencies to explain which public comments were included or excluded from a final government decision. Subsequently, other Chinese localities (e.g., Shandong Province, Xi’an Municipality, and Shantou Municipality in Guangdong) developed local APRs that built on Hunan’s pioneering template.Footnote 45

This longstanding interplay between central and local reform raises the question of whether the top leadership had a master plan or whether the reforms emerged organically through local-level experimentation. While the more concrete instances of reform have emerged from below – illustrated by the early OGI regulations in Guangzhou and Shanghai, and the trend-setting APR in Hunan – it is also true that national legal authorities set the tone for what is politically advisable or even permissible at the lower levels of China’s vast administrative landscape. During the Hu-Wen administration, the Legislative Affairs Office of the State Council launched several initiatives that sent encouraging signals to local reformers around the country. In 2004, it launched a ten-year program to promote “administration in accordance with the law,” which, among other goals, encouraged greater public participation in the drafting of administrative rules and decisions.Footnote 46

Wherever the primary drivers may lie, it is abundantly clear that the reforms have led to profound changes in the way Chinese citizens interact with their government. After the national OGI regulations came into effect in 2008, activists and ordinary citizens began requesting information on how highway and bridge toll money was being used by local authorities, how government decisions have been made in cases of urban housing demolition or land requisition, and how state companies were sold or restructured in different localities. Our chapters are punctuated with examples of how reforms at various levels have inspired citizens to make new and innovative demands on government agencies, including through social media. In Chapter 4, for example, we describe how a high school student in Guangzhou responded to a public bidding announcement about retrofitting metro lines and covering station walls with large stone slabs. Questioning whether the renovation was necessary, he tweeted his concerns on his microblog, gained a wide popular following, and ultimately caused the city’s People’s Congress to downgrade the plan to simply repairing areas with immediate problems.

Chinese citizens have also grown accustomed to being consulted during official decision-making and policymaking – so much so, in fact, that opposition has been fierce when consultation has been denied. In one example, described in Chapter 5, a newly appointed township party secretary in Zhejiang Province skipped annual budget consultations in 2007 in an apparent effort to adopt a town budget before the start of the spring festival holidays. To his surprise, members of the local legislature, media, and citizens responded by mobilizing and demanding that the entire process be restarted.Footnote 47 Similarly, in 2008, when PetroChina tried to build a US$5.5 billion polyethylene plant in Chengdu, several thousand residents poured into the streets to protest. As a participant and local blogger, Wen Di, explained at the time, “What we’re saying is that if you want to have this project, you need to follow certain procedures: public hearing and independent environmental assessment.”Footnote 48

1.3. Principal Research Findings

What, then, do these reforms and associated citizen responses add up to? Have the reforms helped to lower corruption, reduce disputes, and improve conditions in areas like labor relations or the environment? Have they varied significantly across Chinese provinces? What were the primary motivations of the national and local leaders who set the reforms in motion? The next six chapters address these questions in detail as we summarize below.

Transparency Findings

In Chapter 2, the first chapter in our transparency section, we introduce the major transparency policies in China over the course of the reform era, paying special attention to the most prominent example – the aforementioned national OGI regulations, implemented nationwide in 2008, which mandated the publication of documents across Chinese agencies and also created a mechanism for citizens to request government information. (See Figure 4.3 on page 107 for a demonstration of increasing transparency across Chinese provinces.) The chapter describes the international and domestic theories that motivated the reforms, and chronicles key debates at the national and local levels. A critical theme that emerges is that central officials, despite lofty rhetoric, had an instrumental incentive for supporting greater transparency: they saw it as a necessary tool for policing the misuse of public expenditures in far-flung localities.

Chapter 3 picks up this theme by statistically exploring the hypothesis that Chinese transparency initiatives have led to reductions in macro-corruption among subnational officials. To test the theory, we take advantage of archived provincial government websites (2000 to 2011), recording the amount of public information that is available about government structure, processes, and output. The dependent variable, macro-corruption, is operationalized by the amount of misused funds discovered by the National Auditing Office as a share of provincial expenditures. In conducting this analysis, we find robust evidence that increased transparency is strongly associated with reductions in the misuse of public funds (see Table 3.4 on page 88 for a depiction of the relationship).

The last chapter of the transparency section, Chapter 4, examines the causal relationship through case studies of three Chinese localities. In the early 2000s, the well-known leaders of Guangzhou and Chongqing pioneered sharply contrasting methods for economic reform and anticorruption. Through archival research and first-person interviews, we look at the connection between Guangzhou’s early adoption of OGI policies and its success at limiting abuses of authority. In sharp contrast, we show how the state-led, aggressive approach of Chongqing ultimately foundered due to its inability to properly police the guardians.

Participation Findings

In our opening chapter on participation, we track the origins of participatory decision-making in China – from a mass-line remnant of the Maoist era to a modern policymaking instrument. Originally adopted as a means for implementing unpopular price changes, public participation procedures (expert consultations, public hearings, and, more recently, public comment campaigns) have been increasingly utilized by both central and local decision-makers. Whereas only a handful of provinces experimented with participatory decision-making in the early 2000s, today hundreds of legislative and administrative drafts proceed through at least one of these procedures (see Figure 5.1 on page 175). Why are China’s leaders encouraging the public to engage in policy? We put forward a simple proposition: authoritarian policy crafted with public input is less prone to error, noncompliance, and public opposition.

The second chapter on participation tests the impact of participatory decision-making in China by focusing on two key policy arenas: labor and the environment. Taking advantage of the project database, we leverage cross-provincial and temporal variation in the use of participation to measure impact on policy effectiveness, noncompliance, and stability (see Tables 6.3 through 6.6 in Chapter 6). The empirical analysis shows that participatory policymaking was adopted during periods of policy volatility and demonstrates that these approaches were effective in reducing labor disputes, environmental violations, and even mass grievances. We also find evidence that participatory policymaking has contributed to improved labor and environmental conditions, but only in the presence of an active civil society. For example, we found that public consultation on environmental policy resulted in improvements in environmental quality, but only in provinces with the densest civil society networks.Footnote 49 We interpret such findings to underscore that effective consultation requires the active participation of informed and dedicated interests.

The third and final chapter of this section addresses threats to causal inference and measurement problems in our quantitative analysis by presenting a matched case comparison of three Chinese provinces. Sichuan in the west is heavily populated but underdeveloped. Jiangsu in the east is relatively wealthy but heavily polluted. By contrast, Chongqing (China’s newest provincial-level city) has experienced strong top-down leadership and large central transfers. Whereas policymakers in both Sichuan and Jiangsu experimented with participation campaigns to resolve labor and environmental policy challenges, Chongqing’s municipal authorities relied on participation, in combination with large public expenditures and national publicity, to win over public opinion. These case studies reinforce the notion that governance reforms such as participation are adopted out of necessity and under difficult circumstances, lending further confidence to the quantitative results established in the preceding chapter.

1.4. Leadership Transition and Associated Trends

Taken together, the above findings show that official efforts to increase transparency have helped to reduce corruption, while higher rates of participation have enhanced compliance and reduced disputes in the environmental and labor sectors. These findings should be of interest to a Chinese leadership that is deeply concerned about political instability resulting from unchecked corruption, growing numbers of labor disputes, and the proliferation of mass protest incidents. Indeed, our research suggests that Chinese leaders already have an effective toolkit at their disposal, including specific policy measures for enhancing participation and transparency, which could improve the quality of governance on a broader scale if the measures are consistently applied across all Chinese provinces. Yet while our research reveals that concerns over corruption and instability were key motivations for participation and transparency reforms in the past, the current Chinese leadership under Xi Jinping appears to be diluting the governance formula identified in this book by favoring more coercive, top-down approaches. This trend is vividly illustrated in the regime’s heavy-handed anticorruption campaign, its return to the mass-line politics of the Maoist era, and its crackdown on dissent and civil society more broadly.

In many ways, the current leadership prefers a Maoist toolkit and looks to the Party, not the government, as the principal instrument for addressing perceived threats and related governance challenges.Footnote 50 The anticorruption campaign is a case in point. Concerned that rampant corruption is an existential threat to the Party’s legitimacy, the leadership has carried out the most intense and sustained anticorruption campaign in the Party’s history. Overseen by the Party’s Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI), the campaign has disciplined approximately 750,000 violators since late 2012 – including 336,000 officials in 2015 alone, up more than 40 percent from the previous year – for such abuses as hosting lavish banquets, misusing public funds for travel, using government vehicles inappropriately, and constructing luxurious government buildings.Footnote 51 The campaign is popular with the Chinese public and is being carried out by the Party through a secretive and sometimes coercive detention system, known as shuanggui, designed to investigate and discipline members.Footnote 52

Meanwhile, as this anticorruption campaign has raged forward, some promising legal approaches to reducing corruption have faltered. Starting around 2008, for example, several localities around the country began to experiment with reforms designed to publicize the income and assets of government officials.Footnote 53 These efforts culminated in CCDI-sponsored discussions in Beijing in December 2012 that reviewed ways to codify such reforms into law,Footnote 54 just as the anticorruption campaign was getting underway. Even the official China Daily was supportive:

China should learn from conventional practice in its fight against corruption. For instance, making officials declare their personal property has proved an effective way to stop corruption. This system has already been practiced in some parts of China. But the public has always been kept in the dark because the process of declaration is only open to insiders.Footnote 55

These moves inspired political activists like Xu Zhiyong, a prominent lawyer and a founder of the New Citizens Movement, to demand that senior officials also disclose their personal wealth. But Xu and other anticorruption activists were detained by the authorities in April 2013, and Xu received a four-year sentence in early 2014 for disturbing public order.Footnote 56 In addition, local experiments regarding official asset disclosure have lost steam, as have high-level discussions about how to translate such experiments into the country’s legal framework.

Instead of disclosing their assets, local officials are now required to engage in “self-criticisms” – a mass-line procedure that was popular in earlier phases of the Party’s history.Footnote 57 In addition, organizations engaged in activities ranging from business to sports to arts are being encouraged to rectify their ambitions in accordance with communist ethics.Footnote 58 Shortly after the new administration took office, millions of public sector employees undertook refresher courses on Marxism and intensive training on how to be good representatives of the Party and state. Clearly, while modern China has little stomach for mass campaigns on the scale of those that occurred during the Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward, this has not stopped the Party from initiating top-down efforts to enforce compliance. To push their agenda, in fact, Xi Jinping and six fellow members of the PBSC even paired themselves with counties across China. In 2014, Xi was paired with Lankao County in Henan, which he praised for reducing “face-saving projects,” work avoidance, binge-eating and drinking, and abuse of power.Footnote 59

The current anticorruption campaign has also been accompanied by intensified control over civil society organizations.Footnote 60 Chinese nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) already faced many hurdles and challenges, particularly in finding a qualified government agency willing to serve as their professional supervising unit (as required for legal registration). Yet, despite these challenges, the NGO sector has expanded significantly over the past 20 years. More than 675,000 NGOs are now registered with the state, while another 3 million may exist, but remain unregistered, according to Chinese scholarly estimates.Footnote 61 These organizations vary widely – from large, well-funded government-organized NGOs, or GONGOs, to grassroots NGOs with few staff and minimal financial support. They also vary between organizations that focus on the provision of social services to such sectors as the poor, the elderly, and the disabled, to those organizations that are prepared to engage in political advocacy. The latter face greater official scrutiny and have a harder time securing legal registration, although some issue areas like environmental protection have been given more leeway by the authorities.

Chinese NGOs have been looking forward to the prospect of improved legal conditions, including streamlined registration procedures at the national level following direct registration trials that have taken place in several provinces since 2011. In June 2015, however, the CCP announced that the Politburo had decided that party groups should be established in social, cultural, and economic organizations. This announcement not only caused unease among local NGOs but led some Chinese intellectuals to speculate that a creeping totalitarianism was developing in the country.Footnote 62 Subsequently, in April 2016, the NPC’s Standing Committee approved a restrictive Foreign NGO Management Law that places all foreign NGOs under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Public Security – switching supervisory authority away from the Ministry of Civil Affairs – and allows the police to scrutinize the operations of foreign NGOs and interrogate their employees at any time.Footnote 63 Whether foreign or domestic, it seems that NGOs in China are bracing for a new era of enhanced intervention and control.

Do these moves reflect a return to Maoist practices as some observers suggest? Do they also signal a broader rollback of reforms generally, including those that we examine in this study focusing on transparency and participation? The answer to the first question appears to be yes, but the answer to the second question is more complicated.

In general, and as we discuss further in Chapter 8, it appears that the regime has not abandoned the transparency and participation reforms that we chronicle in this study. With regard to transparency, for instance, the Supreme People’s Court moved in late 2013 to release all civil, administrative, criminal, and commercial case records – a decision that applied not just to the high court but to all of China’s 3,000–plus subnational courts.Footnote 64 The Xi administration has also taken steps to disclose every land transaction completed on Chinese soil since the 1990s (including information on buys, sellers, location, land quality, and land-use rights) as well as other data related to leadership biographies, corporate ownership, and government spending. Although movement on participation has been less pronounced, China’s State Council has begun soliciting public opinion not just on government policies but on the legislative agenda of the NPC, providing citizens with an opportunity to participate in agenda setting.Footnote 65 In addition, the CCP’s Fourth Plenum, convened in late 2014, highlighted public consultation as one of the Party’s main pillars of governance and put legal and judicial reform at center stage more generally.Footnote 66

To sum up, we appear to be witnessing a clash, or perhaps a convergence, of distinct toolkits for attacking such stubborn governance challenges as rampant corruption and societal noncompliance with official decisions. Under the Hu-Wen administration, the government increasingly addressed these challenges through transparency and participation reforms that resulted from a combination of local experimentation and central-level encouragement. These reforms were highly instrumental in nature and were primarily designed to monitor subordinate officials and secure useful information about citizen preferences on government decisions. While some related reforms have stalled, such as nascent efforts to promote the disclosure of official assets, the core transparency and participation reforms have largely continued under the leadership of Xi Jinping since 2012. At the same time, however, the current leadership has combined these forward-leaning reforms with a fierce anticorruption campaign, mass-line initiatives, and a general crackdown on civil society – all of which hark back to the Maoist era and show how the CCP is taking on a more direct role in governance.

1.5. Conclusion

The transparency and participation reforms that we examine in this study have helped to reduce corruption and enhance policy compliance in China. Yet these impacts have varied significantly across Chinese provinces and cities, often depending on how vigorously local officials have implemented the reforms in their respective areas. Extrapolating from these empirical findings, a governance adviser to Xi Jinping could logically recommend that he sustain the administrative reforms of his predecessor. Indeed, the Chinese leader should double down, hit the gas pedal, and apply the reforms more consistently across all provinces in order to achieve these impressive governance outcomes on a wider scale.

That said, our analysis also points out that it is not sufficient for the Chinese leadership to implement these reforms in isolation; for the reforms to generate citizen responses and achieve their intended outcomes, they also need to be carried out in a broader societal ecosystem that includes an active media and robust civil society. Our logic is simple on this point. Transparency is effective at deterring corruption if government information is meaningful, if internet and media channels are open, and if average citizens believe they can call out corrupt officials and be reasonably confident that the officials will be sanctioned and the risk of retribution is low. At the same time, public hearings and notice-and-comment procedures are informative when they provide genuine opportunities for critical views to be heard in a policymaking process, including views from groups and individuals who otherwise have limited access to such deliberations. Conversely, transparency is unlikely to reduce corruption and participation will have little impact on policy outcomes when a regime takes steps to suppress public debate, restrict the media and the Internet, and limit space for civil society development. Under these conditions, the governance reforms outlined in this study may inadvertently become the window dressing that critics were so quick to dismiss when the reforms were first enacted. Such signs are already beginning to emerge, as we discuss further in Chapter 8.

Our study also identifies the specific policy perils of curtailing the growth of civil society organizations – particularly for improving environmental conditions across China, a top priority of the Chinese leadership. We find that greater public participation is effective in reducing environmental violations by polluters, as noted earlier, but enhanced participation by itself will not lead to improved environmental conditions; rather, participation must be combined with robust civil society networks for it to lead concomitantly to improvements in water quality in a given province. These findings present a clear policy conundrum for the current leadership. Does it continue to place constraints on civil society, presumably out of fear that Chinese NGOs could one day transform into political organizations and challenge the CCP’s supremacy? Or does it loosen the reins and allow these groups to help combat a key source of mass protest incidents and political unrest in China today (i.e., environmental accidents and degradation)?

These policy and related theoretical questions animate the next two parts of the book, which explore both the drivers and impacts of China’s transparency and participation reforms in greater depth. The final chapter then considers the implications of our research for theoretical debates on Chinese governance and for the future of the Chinese regime more broadly. Put simply, what is the road ahead?