When twenty-three-year-old Peter Green left Newport, Giles County, Virginia, in early September 1850, his plan was to get to Richmond and from there to a Free State. He got only as far as Lynchburg, roughly one hundred miles from his home, when he was intercepted at the Franklin Hotel as he tried to buy a train ticket. When questioned, Green claimed he was a free man going on a visit to Pennsylvania. But it quickly became apparent that his free papers, which he readily produced, were forged. Those who took him into custody found that he was also carrying an atlas, pen, ink and paper – which possibly could be used to forge additional passes as needed – and on which was carefully recorded the mileage between Newport and Richmond. A few weeks earlier, a group of eight slaves from Clarke County, in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, had arrived in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Three of them, Samuel Wilson, George Brocks, and Billy, decided to try their luck in the city, unaware that their masters were hot on their heels. From Chillicothe, Ohio, came word that more than 110 slaves had passed through the town from Kentucky in the six months before October 1850. One slave catcher told a not-too-sympathetic correspondent that, over the spring and summer of 1850, Maryland and Virginia had lost more slaves than in “any former period.” Among them must have been the seven who together fled Maryland in August 1850, five of whom were captured in Shrewsbury, Pennsylvania, one mile above the Maryland line, as well as the ten Virginia slaves who got lost in the Allegheny Mountains and were captured in Bedford, Pennsylvania. These were just a few examples of what, to many Southerners, was a disturbing pattern of slave escapes.

A few of these escapes were nothing if not spectacular. William and Ellen Craft had escaped from Macon, Georgia, over the 1848 Christmas holidays. Phenotypically white, Ellen dressed as a master traveling to Philadelphia for medical treatment; William accompanied her as her slave. Traveling openly by train and boat, they made it to Pennsylvania in just four days. Three months later, Henry Brown came up with the ingenious scheme to have himself crated and mailed to Philadelphia. Hours later he emerged triumphantly from his box at the offices of the American Antislavery Society, if a little worse for wear. Both the Crafts’ and Brown’s escapes were celebrated by abolitionists as feats of daring and a demonstration of the determination of the enslaved to be free. But even in failure, so too were Green’s, Wilson’s, Brock’s, and Billy’s and the many others who fell short of their mark. Not a day passes, one frustrated Maryland editor reported, when one or more slaves did not take a chance on reaching a Free State. The consequent losses, he despaired, were “immense.”Footnote 1

The immensity of the problem, many insisted, was in large part due to interference from outside forces, of abolitionists and their agents, black and white, who seemed to circumvent all the mechanisms slaveholders had put in place to stanch the bleeding. In Peter Green’s case, it was a “scoundrel of a Yankee” who had accompanied him as far as Lynchburg only to abandon him once he was captured. The unidentified Yankee, who we can assume was white, was supposedly part of an organized band of robbers who came south under different guises. Following Green’s capture, a local newspaper called on the community to be on its guard, for, it warned, nearly every area of the upper South had “one or more abolition emissaries in its midst, colporteurs, book-sellers, tract agents, school teachers, and such like characters, who omit no occasion to poison the minds of our slaves, and then steal them.” The list of subversives seemed endless, reflecting a deep sense of slavery’s vulnerability made worse by the inability to control the flow of people and goods on which most of the commerce and culture of these communities depended. Similar warnings came from port cities, such as Norfolk, Virginia, which many observers considered gateways to freedom points at which escaping slaves were aided by Northern free black sailors who found ways to circumvent legal restrictions placed on black crews employed on ships from the North. Some of these ships, one Norfolk newspaper reported, make “the abduction of slaves a matter of trade and a source of profit. Scarcely a week passes that we do not hear of one or more being taken off.” But even more troubling was the fact that these free black sailors indoctrinated “the minds of the slaves with the notions of freedom, and afterwards afford[ed] them the means of transportation to free soil.” It was common wisdom that white and black outsiders were responsible for first corrupting and then encouraging slaves to escape. Peter Green, and any other slave, simply could not have acted on their own.Footnote 2

The losses were staggering. According to Arthur Butler, a senator from South Carolina, Kentucky alone lost $30,000 worth of slaves every year, a figure that rose to as much as $200,000 for the entire border slave states. His colleague, James Mason of Virginia, put the loss at “a hundred thousand annually.” Thomas Pratt, former governor of Maryland, spoke from experience: during his administration, the state lost slaves, valued at $80,000, every year. Never one to miss an opportunity to exaggerate, David Atchison of Missouri, while he could not be more specific, was certain that “depredations to the amount of hundreds of thousands of dollars [were] committed upon property of the people of the Border States of this Union annually.”Footnote 3 These were wildly imprecise figures. But they nonetheless reflected the depth of frustration and the anxiety the flight of fugitives generated as well as the inability to curtail apparent interference from outside forces. Such interference with and pilfering of private property in the South was buttressed by Free State laws, such as Pennsylvania’s (1847), which barred holding suspected fugitive slaves in state prisons. The activities of abolitionists, free blacks, and fugitive slaves only compounded the problem by making it even more difficult, if not impossible, to reclaim slaves once they reached a Free State. Together, laws such as Pennsylvania’s were, Mason declared, the “greatest obstacle” to reclaiming escapees. He reached for an appropriate metaphor to capture the difficulty of reclaiming fugitives: it was, he said, like searching for fish in the sea. Colleagues may have found such tropes inept, but it was the best Mason could conjure up during the heated debate over the need for a new and more effective fugitive slave law. Pratt was more practical. Maryland fugitives did not simply vanish once they reached Pennsylvania; local mobs, made up largely of African Americans, had prevented their return.Footnote 4

These were losses the Slave States could no longer endure. Something had to be done to find a more effective means to reclaim lost slaves as required by Article 4, Section 2 of the Constitution. The 1793 Fugitive Slave Law, Mason and his colleagues believed, had become, over the years, a dead letter. The solution was a new, expanded, and more effective fugitive slave law – a law with teeth – which Mason submitted to the Senate in January 1850. Mason may have drawn on a report of a Select Committee of the Virginia General Assembly, which, after looking into the history of the crisis, made a number of recommendations to address the problem. The report was premised on what, by mid-century, had become a generally accepted historical myth: namely, that Southern states would not have consented to join the Union had the Constitutional Convention not addressed the issue of fugitive slaves. Quoting Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court Joseph Story, in the case of Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), the authors of the report observed that the agreement to return fugitive slaves “constituted a fundamental article, without whose adoption the Union would not have been formed.” The 1793 law was meant to buttress this “solemn compact.” For the first two decades of the nineteenth century, this agreement was widely enforced, until it came under attack, in the wake of the 1820 Missouri Compromise, by political fanatics driven by “sectional jealousy.” A series of personal liberty laws – what the report described as “disgusting and revolting exhibitions of faithless and unconstitutional” legislations – meant that slaveholders could no longer rely on the aid of Free State officers. Not only were fugitive slaves harbored and protected, but “vexatious suits and prosecutions were initiated against owners or their agents, resulting sometimes in imprisonment.” Irresponsible mobs, “composed of fanatics, ruffians and fugitive slaves, who had already found asylum abroad, were permitted by local authorities to rescue recaptured slaves in the lawful custody of their masters, and imprison, beat, wound and even put to death citizens of the United States.” As a consequence, the cost of recapture often exceeded the value of the slaves retrieved. These actions were buttressed by the activities of abolitionist societies, which aimed to destroy slavery by, among other means, sending emissaries into the “very heart of the slaveholding states” to induce slaves to escape. These forays had made slave property increasingly tenuous by imposing what, in effect, was a “heavy tax” on the border states. If an owner wished to reclaim his slave, he must venture into hostile territory, seize the slave himself, march him off to a judge, sometimes over great distances, all the while hounded by hostile forces. And even then, there was no guarantee his property would be returned. Something had to be done immediately if “border warfare,” was to be prevented. The committee recommended the establishment of a federal policing system. Commissioners, clerks, marshals, postmasters, and collectors of customs would be given authority to issue certificates to claimants; marshals would have the power to make arrests and to call out a posse to ensure the return of the slave, all expenses to be covered by “the public treasury of the United States.” Finally, the committee recommended increasing the penalty for obstructing renditions, making “assemblies meant to obstruct the operation of the law” a misdemeanor, and “any death resulting from resistance” a felony.Footnote 5

Mason’s recommended fugitive slave bill not only stiffened the penalties imposed by the original Fugitive Slaw Law of 1793, it also made it easier for slaveholders to reclaim slaves who had escaped to a Free State. Commissioners, traditionally minor legal administrators, were to be vested with expanded judicial authority. Hearings were to be perfunctory and a commissioner’s decisions final and not subject to appeal; suspected fugitives were not allowed to testify on their own behalf or be allowed legal representation; jury trials were not permitted; whenever they suspected there would be community resistance to their decisions, commissioners were empowered to call out a posse to enforce their order, the cost to be borne by the federal treasury. If requested to do so by the authorities, citizens of Free States had to become involved in the recapture of slaves. Those who impeded the application of the law, gave aid to a fleeing fugitive, or refused to aid in the recapture of slaves, faced stiff penalties. It would serve no purpose, Mason insisted, to adopt new legislation without teeth. The new law had to be effective and tailored to meet the needs of new political realities brought on by rising levels of slave escapes and abolitionist activities, which together made slave property increasingly vulnerable.

In early February 1850, Kentucky’s Henry Clay proposed a set of compromise measures that he told the Senate were meant as a balm to soothe his “distracted” and “unhappy country” which, he feared, stood on the “edge of a precipice.” Clay called on both sides to give ground, “not on principle” but “of feeling of opinion” in an effort to solve the pressing problems facing the country following the end of the war with Mexico, which saw the United States acquire vast tracts of land in the west.Footnote 6 The country was mired in a potentially debilitating crisis over what to do with the lands. It was, in part, to address this problem that, in 1847, John C. Calhoun had called for the creation of a unified Southern party to promote Southern interests. He demanded that slaveholders be allowed to take their slaves into the new territories. Such insistence met with stiff resistance from those who believed that the 1820 Missouri Compromise had set the permanent limits of slavery. In 1846, David Wilmot’s demand that the House accept President Polk’s request for additional funds to fight the war with Mexico only on the condition that slavery be banned from any territory acquired as a result of the war became the political marker dividing the two sections. Although what became known as the Wilmot Proviso was never adopted by the Senate, it continued to win support in the House. In addition, all Northern legislatures, bar one, called on Congress to ban slavery in the territories, and to abolish the slave trade in Washington, DC. A few even demanded the total abolition of slavery.Footnote 7 Clay was right: the country was in crisis.

Clay included Mason’s bill as part of his Compromise, which, he hoped, would address the outstanding concerns of both sections. Under his recommendation, California would enter as a Free State, the residents of the Utah and New Mexico territories were vested with the power to determine whether they entered the Union as a Free or Slave State; the contested lands between Texas and New Mexico were to be finally adjudicated, with Texas giving up much of the land it now claimed; and the slave trade but not slavery was to be abolished in Washington, DC. Clay’s plan applied five plasters to five seeping sores. Over the next nine months, the attention and energy of both houses of Congress would be focused, almost exclusively, on the final terms of the Compromise. Try as they might, the fugitive slave wound continued to seep. In fact, for many in the North, especially those opposed to the extension of slave territory, the law became the one element of the Compromise that was totally unacceptable. In the South, its adoption and enforcement was seen as the ultimate measure of the North’s commitment to a resolution of the crisis. Opponents of the law cried foul: the powers vested in commissioners were unprecedented and unconstitutional, and the differential payments they were to receive – $10 if their decision favored the claimant, and $5 if it did not – struck many as grossly unfair and an incentive, the equivalent of a bribe, to commissioners to rule in favor of the slaveholder. Two pillars of the judicial system, the right to a trial by a jury of one’s peers and the right to habeas corpus, seemed to be eviscerated by the proposed law. Without these rights, free blacks could fall victim to false claims by slaveholders. As it stood, the law would give a free hand to kidnappers, a problem that had bedeviled the residents of black communities for decades. The steep penalties imposed on those who aided accused fugitives to elude their captors violated the biblical command to aid the poor, the hungry and weary traveler. In effect, it turned the average citizen into a slave catcher. The fact that the cost of rendition was to be borne by the national treasury imposed a hidden tax on all citizens. And the authority to call out a posse created a national police enforcement mechanism. The law, moreover, did not provide a statute of limitation. A fugitive who for years had been living as a free person, had started a family, had been gainfully employed and was a productive member of his community, could be snatched from his family and community and returned to slavery at any time. Salmon Chase of Ohio spoke for many opponents. The law, he argued, was illegal if for no other reason than the Constitution did not grant Congress the power to legislate for the return of fugitive slaves. “The power to provide by law for the extradition of fugitives is not conferred by an express grant,” he told his colleagues. “We have it, if we have it at all, as an implied power; and the implication which gives it to us, is, to say the least, remote and doubtful. We are not bound to exercise it. We are bound, indeed, not to exercise it, unless with great caution, and with careful regard, not merely to the alleged right sought to be secured, but to every right which may be affected by it.” Prior to the decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, Chase observed, each state had developed “its own legislation to address the issue.” The new law would destroy that tradition and shift enforcement to the federal government.Footnote 8

Those who argued the need for a new law considered the old law a dead letter. The 1793 law relied too heavily on state officials to enforce its provisions, mandated penalties were distressingly minor, abolitionists and their black supporters either ignored or defied rulings, and Northern states had set in place laws that undermined its effectiveness. Mason demanded one thing of the new law: it had to impose more draconian enforcement mechanisms. Without them, the citizen’s claims would not be adequately addressed. It is the duty of government, he argued, to protect its citizens, “not merely to give them a remedy; but if one form of remedy will not accomplish the end, then to enlarge it in every possible respect till it becomes effectual.” If that could not be done then the government was obligated to indemnify the claimant for any loss that resulted from inefficiency or inaction. Maryland’s Thomas Pratt offered a supportive amendment to Mason’s bill, which called on the federal government to indemnify slaveholders for any loss they may incur as a result of negligence or inactivity on the part of federal officials. A vote in support of his suggestion by Northern senators, Pratt almost pleaded, would give the South “substantial evidence” of the North’s commitment to do justice to those who lost their property. Without indemnification, Mason threatened, slaveholders, and by extension the South, would be forced to take “their own protection into their own hands.”Footnote 9 Pratt’s amendment failed to win support, but, in the end, the law did mandate that the federal treasury cover the cost of returning captives.

Henry Clay insisted that the right and most effective way to address Northern concerns about the denial of trials by jury was first to return captives to the states from which they escaped and there to allow a hearing before a jury. This, he suggested, was one practical way to address the many petitions Congress had received calling for trials at the point of capture. The place from which the alleged fugitive had escaped was, Clay countered, the only location where, under the Constitution, a trial was even permissible. His proposed solution had one additional merit: it would cause “very little inconvenience.” William H. Seward, of New York, and other Northern senators, countered that jury trials had to occur at the place where the accused was seized. Anything else would not guarantee a fair and impartial hearing. William Dayton of New Jersey went a step further: in all hearings before commissioners, depositions had to be authenticated and proof provided that the person claimed was a fugitive. Proof must also be provided that slavery existed in the state from which the accused had escaped. Dayton’s proposal was meant to address what many saw as a lax and total reliance on Southern courts for verification and certification. All a slaveholder had to do was apply to a local court for a certificate confirming that his slave had escaped. Only after these conditions were met would the commissioner be able to issue a warrant for the fugitive’s return. But if the accused denied he was a fugitive, a jury of twelve had to be empaneled to try the case. This was clearly a blocking mechanism aimed at delaying, if not impeding, hearings. Mason rejected these proposals out of hand: jury trials, he knew, could cause interminable delays and were nothing more than devises meant to disrupt enforcement. George Badger of North Carolina agreed; trials by jury at the place of capture were meant to prevent extradition through interminable delays and appeals. Such proposals, he responded, supposed “us so stupid as not to be able to see through the most shallow artifice, or detect the most clumsy device of concealment.” All talk of jury trials, whether in the North or the South, was nothing more than a “miserable expedient” meant to deny slaveholders the right to reclaim “our property.” Mississippi’s Jefferson Davis, who expressed little interest in the law, convinced it would not “be executed to any beneficial extent,” nonetheless condemned the calls for jury trials in the places where fugitive slaves were apprehended as a violation of state rights. Clay’s fellow Kentuckian, Joseph Underwood, thought the offer of a trial in the South, once the slave was returned, merited serious consideration, as it provided a way out of a sticky political impasse. It had the additional advantage of mollifying Northern opinion without conceding the constitutional need for a speedy return of captives.Footnote 10 But Underwood’s amendment generated little support.

There would be no jury trial at either the point of capture or escape, although throughout the 1850s those who applied the law would continue to insist, in the face of all evidence to the contrary, that accused fugitives could go to court in the South to challenge their status. But the issue did not die and reappeared frequently in subsequent congressional debates. During his maiden speech on the subject of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1852, for example, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts raised the issue in his call for the law’s repeal. Lewis Cass, Democrat of Michigan, and James Cooper, a Pennsylvania Whig, both of whom had voted for the law, now recalled that, at the time, they had raised the question with Southern senators and were assured that there was no need for such a provision, as trials were available to those who requested them in the South. In the face of Sumner’s criticism, Cass now seemed to back away from his original endorsement, wondering if the provision for such trials already existed, why it was not explicitly articulated in the law. By not doing so, he lamented, supporters of the law had paid a political price. “If that provision had been inserted in the bill as it was finally passed,” he now admitted, “it would have taken away a great many of the objections to the law.” Those outside of Congress who supported the law also found themselves at a disadvantage. A correspondent of John Floyd, governor of Virginia, wondered if there was a provision in state law allowing for jury trials for returned slaves who claimed they were free. The existence of such a provision, he believed, would go a long way to silence critics, especially abolitionists, “whose infernal system of falsehood and misinterpretation is pursued with all the zeal of blind and traitorous fanaticism.”Footnote 11

Mason also gave no ground on the issue of habeas corpus. Robert Winthrop of Massachusetts argued that a commissioner’s certificate should never invalidate a habeas corpus ruling by a state judge. Mason countered that commissioners were not empowered to try the question of “freedom or slavery”; their sole role was to determine if the person brought before them was a slave and whether he had escaped from the claimant. Neither Congress nor state legislatures, he reminded Winthrop, were permitted to address the question of habeas corpus except in cases of invasion or rebellion. Furthermore, a commissioner’s certificate of rendition was “conclusive evidence” that the fugitive was held “in custody under the provisions of the law” and so trumped any writ issued by a state judge. These concerns about the rights of fugitives Mason dismissed as misplaced. The constitutional mandate was clear and to the point: fugitives from labor “shall be delivered up.” Following delivery, he conceded, “the title will unquestionably be tried,” but it would be “utterly unaffected by any adjudication as to the right of custody upon the mere question of surrender.” Underwood again tried to bridge the divide with an amendment that once again raised the issue of a trial: if a fugitive should claim to be free upon return, the claimant would post a bond of $1,000 so the claim could be heard by a local court. Mason objected to the bond requirement, admitting something that most Southerners knew from experience; in most cases, owners found it necessary, as he delicately put it, to “dispose” of returned slave.Footnote 12

Throughout the debate, which lasted nine months, Mason did not give an inch. His rejection of the guarantees of habeas corpus and trial by jury were freighted with political and judicial significance, so much so that, before President Millard Fillmore approved the law, he asked his attorney general, John J. Crittenden, for his opinion on whether the last sentence of Section 6 of the law in effect suspended habeas corpus in cases involving fugitive slaves, as most opponents claimed. The section was unambiguous. It declared that fugitives did not have a right to testify at their hearings, that the certificates granted by commissioners were final and empowered claimants to return fugitives to the state or territory from which they escaped, and, most tellingly, that certificates of rendition were immune from “all molestation of such persons by any process issued by any court, judge, magistrate, or other person whomsoever.” How else to interpret the molestation clause but as a suspension of habeas corpus? Crittenden submitted his opinion the very day the president put his signature to the law, which suggests that the issue had been under review by the administration for some time. Crittenden’s conclusion was that it did not. But his reasoning seems strangely circuitous: it did not, because the law said nothing about habeas corpus; that under the Constitution, Congress could only suspend the writ in times of war; that, clearly, Congress had no intention to suspend it; and, finally, there was no conflict between the law and habeas corpus in “its utmost constitutional latitude.” Crittenden pointed out that the ruling of the Supreme Court was clear: once a person charged is under “the sentence of a competent jurisdiction,” the judgment is conclusive. There was simply no appeal to the decisions of a “tribunal of exclusive jurisdiction.” All the law did was provide a more effective mechanism for the securing of fugitive slaves who have “no cause for complaint,” because it did not provide any additional coercion to that “which his owner himself might, at his own will, rightfully exercise.” Rather, its aim was to impose an “orderly, judicial authority” between fugitive slaves and owners and, as such, offered a form of protection to both parties. Its intention, he concluded, was the same as that of the 1793 law. A certificate of rendition was nothing more than a “sufficient warrant” for the return of a fugitive and, he concluded, did “not mean a suspension of the habeas corpus.”Footnote 13 There was little difference between Crittenden’s and Mason’s positions. Both skirted the question, for while the law did not technically suspend the writ of habeas corpus, it clearly gave writs little effect. All that was needed was a certificate from a commissioner based on largely ex parte evidence from a distant jurisdiction, one that was largely impossible to verify, to preclude an appeal for a writ. Over the next decade, hearings before commissioners would test the law’s mandate on habeas corpus. Supporters of the law in Congress and the White House had spoken with one voice.

The law passed the Senate on August 23rd by a vote of 29–12 and, subsequently, the House, by a margin of 109–76. Many Northerners from both parties abstained or found it politically convenient to be absent at the times the votes were taken.Footnote 14 Acceptance of the Compromise had only been made possible by Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas’ deft political decision to separate Henry Clay’s Omnibus bill, as it was called, into its constituent parts and then marshaling sufficient support for each to assure passage. But there were deep divisions in Congress. For some Southern senators, such as Jefferson Davis, the Compromise was nothing more than a “great medicatory measure.” To Thomas Benton of Missouri, its elements were a “patchwork of statutory legislation...dignified with the name of compromise.” Hopkins Turney of Tennessee employed an interesting measure: how many Southerners, he asked rhetorically, voted for the bill to abolish the slave trade in Washington, DC, and for the admission of California as a Free State; and how many Northerners voted in support of the Fugitive Slave Law. By this measure, both parties had acted in bad faith. The different elements of the Compromise were nothing more than “force bills” pushed through Congress against the will of the minority. As far as William Seward was concerned, the Fugitive Slave Law was nothing more than an attempt to impose on “the free States...the domestic and social economy of the slave States.”Footnote 15

Like Turney and others in Congress, historians have questioned if what was finally agreed to was in fact a compromise, one in which both sides conceded important ground in the interest of a broader resolution. It was what Henry Clay had hoped to achieve with his original proposal. David Potter has called it an “armistice, certainly a settlement, but not a true compromise,” a conclusion with which William Freehling agrees, although he calls it a “sellout” to Southern demands that did little to “defuse explosive questions.” Paul Finkleman dismisses it out of hand as the “Appeasement of 1850,” an “utterly one-sided” concession to Southern demands. Allan Nevins was more sanguine: the Compromise, he writes, overrode and rebuked “the extremists” and so held the center together.Footnote 16 But Turney’s questions to his colleagues went largely unanswered. As he lay on his dying bed, John Calhoun, in one of those rare prescient moments, told James Mason: “Even were the questions which now agitate Congress settled to the satisfaction and with the concurrence of the Southern States, it would not avert, or materially delay, the catastrophe. I fix its probable occurrence within twelve years or three Presidential terms....The mode by which it is done is not so clear; it may be brought about in a manner that none now foresee. But the probability is, it will explode in a Presidential election.”Footnote 17 Unlike the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which resisted efforts to derail it for thirty-four years, until the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the 1850 agreement did little to quiet the roiling political waters. Every instance involving the recapture of an escaped slave in the North had the potential to make those waters more turgid and a danger to the future of the compact.

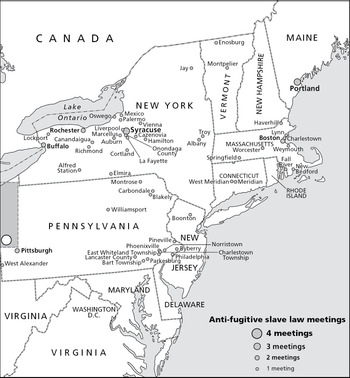

Robert Barnwell Rhett, Calhoun’s fellow South Carolinian, who had nothing good to say about the Compromise because he believed it violated state rights, wondered how the new law was to be effectuated when it was not in harmony with the “opinions and feelings of the community” in which it was to operate.Footnote 18 His concerns were soon to be confirmed; over the next two months and deep into 1851, scores of meetings were held throughout the North to condemn and declare open defiance of the law. Some of these meetings were called in the wake of particular fugitive slave cases, but the great majority was community-based responses to the law and a declaration of support for endangered fugitive slaves who had taken up residence in these communities. African Americans, those who were most vulnerable to the law, called the earliest meetings. All of these, not surprisingly, took place in cities – Boston; New York City; Syracuse; Rochester; Buffalo; Chicago; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Cleveland; Columbus, Ohio; Portland, Maine; and elsewhere – where blacks had a large enough presence. These meetings were followed, in a matter of days, in many of these same cities, by interracial assemblies, which drew on the long traditions of abolitionist activity. Meetings were also organized in small towns and villages in areas noted for strong abolitionist traditions, areas that, over the years, had become magnets for fugitive slaves who had settled and started new lives there. Fugitive slaves actively participated in these meetings. At the conclusion, associations were organized to resist enforcement of the law and resolutions passed condemning the law as inhumane and unconstitutional and calling for its repeal or amendment. A number of church associations, either through public meetings or in their annual synods, also condemned the law. Defiance of the law, Benjamin Quarles has written, became a “new commandment.” By the end of October, the editor of the Daily Union despaired that abolitionists, Free-Soilers, “higher law prophets and negroes”– a “motley gang” of every “color, caste and character” – had held “mongrel gatherings” in “every city, and nearly every village of the North,” which made “nights hideous by their turbulences and folly in negro churches, at cross-roads, in barns and market houses.” This plague had to be stayed, by the good people of the Free States, he pleaded.Footnote 19 The anti-law element seemed to be everywhere threatening implementation of the law as well as the country’s future.

Unnumbered Map 1. [Thanks to Erica Hayden for preparing the map. Note: I was unable to locate the site of a handful of meetings on a modern road map.]

Aware that Fillmore was about to put his signature to the bill, African Americans called a meeting in Springfield, Massachusetts, under the leadership of James Mars, a Methodist clergyman. The law, the meeting declared, was not only disastrous for those who were now enjoying “a state of normal freedom,” but also for “every free colored person” who at any moment was liable to be “claimed and forced into bondage.” The meeting welcomed all fugitives and pledged to defend them with arms if necessary. Days later they formed a vigilance committee.Footnote 20 Fourteen months later, after a meeting with John Brown, who would, in 1859, lead an attack on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, the committee reorganized as the United League of the Gileadites. Forty-four blacks signed the pledge to defend the community against any attempt to retake fugitives. Twelve have been identified. Five were laborers; the others included a barber, a cook, a soap seller and a whitewasher. The occupations of two are not stated and one, Anna Johnson, aged twenty-four, was married to Henry Johnson, aged twenty-five and a laborer. Six of the members were born in Slave States, including William Green, the whitewasher, and a fugitive slave who had escaped from the Eastern Shore of Maryland around 1840. The League, which pledged to give “notice to all members in case of an attack upon any of our people,” and to make plans to ensure that no fugitives were removed from the city, took its name from the biblical story of the allies of Gideon who, as Tony Horwitz has written, “guarded fords across the Jordon River and slew wicked Midianites fleeing across it.”Footnote 21 Earlier, Brown had been instrumental in the formation of a similar organization in Chardon, northern Ohio. The Chardon Fugitive Guards, an armed company of fifty of the town’s “most respectable, influential, and wealthy citizens,” pledged to resist the new law and “the officers of the government with the force of arms, and if necessary, sacrifice their fortunes and their lives in resisting them.” Nothing is known about the operation of either league or even if they remained active, but the fact that no fugitives were returned from either place suggests that slave catchers gave these areas a wide berth.Footnote 22 There were other vigilance committees scattered throughout the North – in Philadelphia, New York City, Boston, and Pittsburgh to mention a few. Richard Hinton, a John Brown biographer, recalls the existence of similar organizations all along the shore of Lake Erie between Syracuse and Detroit. Some, such as the one in Kenosha, Wisconsin, were formed in the wake of the law’s passage. Others, such as the Philanthropic Society in Pittsburgh, had a long and distinguished history reaching back to 1834, and yet others, as in the case of Detroit’s, would be called on at a moment’s notice to address specific incidences.Footnote 23

The Springfield gathering was the first of a number of meetings organized by African Americans in the weeks after the law came into effect. In Lockport, New York, north of Buffalo, they pledged to resist “even to death” any effort to retake fugitives living in or passing through the town. African Americans in Portland, Maine, formed a vigilance committee, convinced there was no alternative remedy left them but “to solemnly warn our fellow-citizens that, being left without legal and governmental protection for [their] liberties,” they were obliged to protect their rights and freedom “at whatever cost or risk.” A Chicago meeting, in late September, condemned the law’s tendency to enslave “all colored men,” as it contained no provisions to defend blacks against false claims. The meeting formed a liberty association with an initiation fee of 25 cents and weekly dues of 10 cents, the money to be used to provide “mutual protection” against the law. Weeks later, the association was reorganized as a “Colored Police Organization” made up of seven divisions, each of six people, to defend the city at night.Footnote 24 Blacks in the little town of Elmira, New York, also formed a vigilance committee and pledged, if they discovered any person “aiding or making themselves a tool of the slave-catcher,” to “meet them as enemies.” Their counterparts in Columbus, Ohio, seemed not as committed to absolute resistance to the law. While the meeting – presided over by John Mercer Langston, an Oberlin graduate – called for the formation of a vigilance committee, it pledged that no fugitive would be taken in the city until they had done all in their power “to secure his or her release,” a rather uncharacteristic qualifier for a black meeting. The meeting also called on any fugitive living in the town to go to Canada.Footnote 25

A meeting of blacks in Syracuse implicitly rejected such options when they formed a vigilance committee. They instead pledged to protect themselves, and families, to “wear daggers in [their] belts” and to “take the scalp of any government hound, that dares to follow on our track,” as they were resolved to be free. They rejected the idea of flight, first, because they had committed no crime “against the law of the land, second that resistance to tyrants is obedience to God, and third that liberty which is not worth defending here is not worth enjoying elsewhere.”Footnote 26 One of the participants in this meeting, Rev. Jermain Loguen, may not have thought he had committed a crime against the country, but he was a fugitive from slavery in Tennessee. So was William Craft, who participated in the first meeting in Boston at the end of September. Since their escape he and his wife had become fixtures in the city’s black community. The meeting was chaired by Lewis Hayden, an escapee from Kentucky, a few years earlier. Hayden called for “united and persevering resistance” to the “ungodly anti-republican law.” The “god-defying and inhuman law,” the meeting declared, was a violation of human rights. The meeting called for the formation of a “League of Freedom” and insisted that blacks remain in the city and resist any attempts to enforce the law. The gathering issued “The Fugitive Slave Appeal,” which called on citizens of good faith to “exert a moral influence towards breaking the rod of oppression.” A second black meeting days later repeated the pledge of resistance and argued in part that, as South Carolina imprisoned black seamen for fear they may foment rebellion among the slave population, Massachusetts, and especially Boston, should imprison slave hunters on similar grounds.Footnote 27

Two meetings were held the same day in western Pennsylvania, one in Pittsburgh and the other across the river in Allegheny City. Speakers such as Rev. Charles Avery – a supporter of black causes, and the person for whom the Avery Institute, which educated a generation of African Americans, was named – questioned the constitutionality of the law for its denial of trial by jury and its suspension of habeas corpus for the accused. He called on Congress to repeal the law and on communities to treat as lepers anyone who accepted a commission. Avery laid down the political markers, which other speakers eagerly followed. To raise questions about the constitutionality of the law and to defy its application was to reject the apparent legislative “compromise” crafted by the majority of Whigs and Democrats in Congress. In fact, the first meeting condemned those in the state’s congressional delegation who voted for the law. They also adopted a series of resolutions that, among other things, condemned the law for encroaching on the rights of citizens of Free States; for converting men into chattel instead of securing liberty for the oppressed; for bribing commissioners to rule in favor of masters; for violating the principle of trial by jury; and for making it easy for masters to call for the aid of city sheriffs and federal marshals on the mere suspicion of community opposition to the return of a fugitive. The meeting called on state newspapers to publish a “black list” of all those who accepted commissions.Footnote 28

In announcing their determination to stay put and resist the law, African Americans asserted their sense of belonging to what they considered free spaces, which they had built over decades. In these spaces they provided the requisite institutional structures, including churches, schools, and benevolent societies. Whites in these cities, many of whom had no known abolitionist background, also joined the protest against the law in the days after blacks had rallied. Two weeks after the first meeting in Syracuse, for example, an interracial meeting, presided over by the city’s mayor, agreed to form a new vigilance committee made up of both blacks and whites. Jermain Loguen predicted open resistance to the law. The people of Syracuse and of the entire North, he implored, had to decide to meet tyranny with force or be subdued by it. He made it clear he had refused all efforts by friends to buy his freedom. To do so would be to “countenance the claims of a vulgar despot of my soul and body.” Loguen spoke for many throughout the North: “I don’t respect the law – I don’t fear it – I won’t obey it! It outlaws me, and I outlaw it, and the men who attempt to enforce it on me.” As if to confirm that the city and its black community was free soil and protected space, the meeting declared Syracuse an “open city” from which no fugitive would be taken.Footnote 29

Ten days after Boston’s first meeting, 3,500 gathered at Faneuil Hall to oppose the law. Speakers included Frederick Douglass, Wendell Phillips, Theodore Parker, and Charles Lennox Remond – leading lights in the struggle against slavery. Constitution or no Constitution, law or no law, one speaker promised, no slave would be taken from Massachusetts. The meeting agreed to form a new vigilance committee. A subcommittee comprised of some of the best legal minds in the state was dedicated to challenging the law in court. The group of lawyers would come to the aid of the Crafts a few weeks later when two agents attempted to return them to Georgia. It is not clear how funds to finance the committee’s operations were raised, but some of the lawyers undoubtedly contributed their services pro bono. In other areas, such as New York City, blacks held a series of benefit concerts to raise money for their efforts. During the last two months of 1850, the Boston Vigilance Committee helped forty-six fugitives to places of safety in other parts of the state and, in the case of John Thomas and his wife, to Canada. The Crafts were sent to England. It is not clear from the records that all of these fugitives were living in Boston at the time; some may simply have been passing through the city on their way elsewhere. The pace of assistance continued in 1851; the committee aided eighty-four on their way, the majority to Canada. In the month of November 1850, the committee also posted three hundred handbills throughout the city warning of the presence of slave catchers. It also paid for the lodging, boarding, and transportation of fugitives. Many of them found temporary refuge at the Haydens’ until it was safe to move on.Footnote 30

As can be seen from the map, many meetings were also held in small towns and villages – some of them within relatively easy reach of large cities. There were thirty-one meetings, for example, in and around Cleveland, Ohio, between October and November 1850. The same pattern held around Ashtabula on Lake Erie and east of Cleveland. Many of the places can no longer be located on a modern map. This was an area strongly represented in Congress by some of the most strident opponents of the law, including Joshua Giddings and Ben Wade. It was an area settled largely by migrants from New England and, over the years, had developed a reputation for protecting fugitive slaves who had made the town and villages their home. Elisha Whittlesey, the comptroller of the Treasury in the Fillmore administration, and a resident of the Western Reserve of Ohio, recalled that many of his neighbors “including clergymen [had] been engaged for years in harboring, rescuing and running negroes.”Footnote 31 Reports of these meetings made it a point to emphasize that those who participated were of all political persuasions. Giddings spoke at one Painesville meeting where he reiterated his position that Congress had no power to legislate on fugitives. Like Salmon Chase, he insisted that the so-called fugitive slave clause of the Constitution was solely a compact between the states. At a series of meetings in Windsor, Ohio, resolutions condemned the law as a violation of the Constitution, criticized those who voted for it, and promised protection to any slave who came among them. The entire county, a local historian has observed, was a “no-man’s land insofar as slave catchers and owners were concerned,” made so by organizations of militant abolitionists who were “not averse to using violence to protect charges.”Footnote 32 There was a similar pattern of meetings in and around Richmond in eastern Indiana, an area heavily influenced by the Society of Friends and with a long history of Underground Railroad activities. Thirteen meetings were held there in an eight-month period between October 1850 and June 1851.Footnote 33

But it was not all clear sailing for those opposed to the law. Supporters of the law and, by extension, the Compromise, managed to mount a number of challenges. A meeting in Dayton, Ohio, in mid-October 1850, recommended a series of typical resolutions opposing the law ending with a call for its repeal. These were opposed by Clement L. Vallandigham, a leader of the state’s Democrats, who declared his support for the Compromise and criticized efforts to whip up public opposition to the law. It was the duty of all “good citizens,” he declared, to obey the law. Not to do so was to encourage further agitation that only endangered the Union. In response, organizers tried unsuccessfully to adjourn the meeting. Vallandigham moved quickly to organize a counter demonstration in support of the Compromise measures. They were, he maintained, the best way to quiet the vexed question of slavery, which had long agitated the country. Vallandigham invited Judge Joseph H. Crane, a former congressman, to preside, but Crane declined because of frail health. In a letter read to the meeting, Crane made it clear that what mattered most was enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law. He drew on Attorney General Crittenden’s arguments to justify the law’s existence. The meeting declared the nation in “imminent peril” from years of ceaseless abolitionist agitation. The Union as it is, therefore, had to be defended at all costs and that included the law, which the meeting endorsed as a “necessary enactment.”Footnote 34

From Chicago came the first open defiance of the law by a municipal corporation – the majority of whose members were Democrats who, at least on the national level, were ardent supporters of the Compromise. The law, the city council declared on October 21, was “cruel and unjust.” The following day, a public meeting endorsed the council’s position. During one of the speeches, a copy of the law was trampled underfoot. Stephen Douglas, the engineer of the Compromise’s successful passage through the Senate, hurried back to Chicago to repair the damage. Three days later, in an address lasting three and a half hours, Douglas condemned the actions of the council and defended the Compromise, by which, he maintained, no side had gained an advantage. Aware of what mattered most to the four thousand who gathered to hear him, Douglas, who must have known better, nonetheless assured his listeners that the Fugitive Slave Law did not violate the right of either a trial by jury or habeas corpus. The next evening, the Council reversed itself in spite of the views of a large public meeting, which had met earlier in the day, at which Douglas’ interpretations of the law’s effects were roundly condemned. A contentious pro-Douglas meeting on October 26th broke up without passing any resolutions. There the matter rested until the council revisited the issue at a meeting on November 29th. Although its original resolutions were softened slightly, the council stuck to its guns: the law, it reaffirmed, was “an outrage,” and, as such, state officers did not have to comply with its requirements. While the council’s original vote was almost unanimous, this time its criticism of the law was carried by a narrower margin of 9–3.Footnote 35

Criticism from the Chicago City Council and the many public meetings that were held during the last three months of 1850, while galling to supporters of the Compromise, was nothing compared to the vitriol that greeted foreigners, especially those from Britain who condemned the law. American nationalists, and especially Southern slaveholders, had always been sensitive to British criticism, especially so in the years since West Indian emancipation in 1834. Such criticism was like salt poured into the raw wound of slavery. When, for example, a meeting in Cork, Ireland, chaired by the city’s mayor, condemned the law and declared its solidarity with the slaves, one editor dismissed such sentiments as the product of an “ignorant and holy zeal” on the subject of slavery. What, he wondered, could be said of men who allowed twenty thousand “starving persons to howl with hunger, and hundreds of them to perish?” No slave in America, he continued, had “to eat the pairings of potatoes, picked from the...gutter of a public street.”Footnote 36 The editor spoke for many worried by the potential impact of such criticism from abroad at a time when the country was wracked by political uncertainty. The presence of scores of fugitive slaves in London, including the recently arrived Crafts and Henry Box Brown, and their public condemnation of the law, only heightened American sensitivity to British criticism. Henry Highland Garnet, who as a child had escaped slavery with his family, and who in 1850 was on a lecture tour of Britain, exploited the presence of Lajos Kossuth in the United States to raise an unfavorable parallel between the Hungarian’s struggle against Austrian oppression and the slave’s fight against American slavery. How, he asked, could Americans rally to the support of Hungarian independence while they continued to oppress their black population? In Britain, he wrote home, Henry Clay, James Mason, and other supporters of the law, were spoken of in the “same scornful breath” as the Austrian general who crushed the Hungarian uprising.Footnote 37

The arrival of George Thompson, the British abolitionist and Member of Parliament, in Boston, in the fall of 1850, as the city was engulfed in the debate over the law, confirmed for many Americans Britain’s continued interference in their domestic affairs. It was Thompson’s second visit to the United States. His first, in the mid-1830s, had so stirred up anti-abolitionist sentiment that he was forced to flee ahead of an angry mob. Initially, his second tour went off smoothly, until the welcome meeting organized by his Boston friends in mid-November. An estimated three thousand packed the hall. Blacks and women occupied the galleries, but those in the main hall were unfriendly and prevented the speakers, including William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Frederick Douglass, and Thompson himself, from speaking. They cheered for Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and the Union, whistled Yankee Doodle, swayed “to and fro like big waves,” one unfriendly newspaper reported, “while all manner of noises filled the air.” The same newspaper dismissed Douglass as “that black scab on the face of humanity.” The breakup of the meeting also provided an opportunity for anti-abolitionists and supporters of the law to unleash a torrent of abuse against foreign interference in the country’s affairs. Thompson was described variously, and always unfavorably, as the “British meddler,” the “mad Englishman,” a member of the British Parliament for “the lowest and vilest part of Cockneydom,” a “paid spy of a hostile government,” imported by “abolitionist agitators” to “stir up the negro race to revolt and bloodshed” at a time when the country was deeply divided.Footnote 38 Henry Clay wondered aloud in the Senate if the British would allow an American member of Congress to peddle such daring, impudent, and insolent drivel in London and not drive him out on a rail. Thompson was, Lewis Cass of Michigan agreed, a “vile disturber of the public peace.”Footnote 39 A couple of days later, Boston blacks softened the blow of the failed meeting by providing a warm welcome for Thompson at the Belknap Street Church. Much of the rest of his visit went smoothly until his visit to Springfield, Massachusetts, in April 1851, when a mob hung him in effigy.Footnote 40

By the time of Thompson’s return home in mid-1851, the level of public agitation over the law had eased somewhat, although it never abated entirely. Anti–Fugitive Slave Law meetings continued to trouble supporters of the law if only because of their geographical reach and concentration. They were more than a New England and, especially, a Massachusetts phenomenon, as Allan Nevins has argued.Footnote 41 Every instance involving the recapture of a runaway would rekindle the agitation. Overall, the frequency of these public expressions of opposition deeply concerned those who saw the Compromise as the most hopeful resolution to a crisis that had dogged the country for decades and which, since the end of the war with Mexico, had grown in intensity. One editor put it bluntly: if the Fugitive Slave Law was the most critical component in what he called “the great scheme of adjustment and pacification” then something had to be done to dissuade its critics. When, he worried, “meetings are openly held in northern cities by the men of color and abolitionists, and resolutions are adopted to resist the law of the land, at the risk of shedding blood, does it not become the friends of law and order, and of the constitution itself, to meet in overwhelming force and counteract open rebellion by the moral force of public opinion?”Footnote 42

There were meetings in support of the law, but their results, much to the disappointment of the editor, were not always easy to measure. I have identified twenty-five meetings in the weeks between late October 1850 and early 1851. Twenty-one of these took place in the North; four in the South. Of the Northern meetings the majority, not surprisingly, occurred in major cities, such as New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, with strong commercial ties to the South. The exception was Cincinnati, which had strong links to the South, but hosted only one relatively minor gathering. There were a few meetings in small cities and towns in the East, such as Geneva; Utica; and Tarrytown, New York; Bath, Maine; and Manchester, New Hampshire. Only four meetings took place in the Old Northwest – in Belleville, Illinois; Massillon, Ohio; Dubuque, Iowa; and Newcastle, Indiana. The Southern meetings were held in St. Louis and Benton, Missouri; New Market, Virginia; and Mobile, Alabama. These do not include the many meetings in the South that were called to express opposition to the entire Compromise as something that offered little by way of guaranteeing the future of slavery in the newly acquired territories.

Sixty years ago, Allan Nevins described these meetings as “largely spontaneous”; they were anything but. They were, in fact, carefully orchestrated and led by prominent local merchants, bankers, manufacturers, professionals, and politicians. In defending the law and the Compromise, they aimed to reaffirm close commercial and political links between North and South. These commercial links were, for example, what made New York City what it was. Two-thirds of the South’s imports and exports, estimated to be worth $250 million, passed through the city. It was reported that, in 1849 alone, the South bought over $76 million worth of merchandise in the city. If neither Whigs nor Democrats could protect these vital connections, organizers proposed the formation of a new national political party that would isolate both the abolitionist and proslavery extremists, the better to ensure the survival of the Union as they knew it. One editor saw these meetings as having long-lasting political consequences, as they promised to influence future elections and so silence the demagogues.Footnote 43

The first of these “cotton meetings,” as an opponent dismissed them, took place at Castle Garden, New York City, in late October 1850. Nearly three thousand of the city’s “bone, sinew, wealth, enterprise, intelligence and moral worth,” one friendly editor pointed out, had signed the call for the meeting. They were all devoted to the “Union and the constitution,” and hated “demagogueism, anti-slavery, anti-rent and socialist agitation.” It was time, he declared, for the “conservative portion of society to arouse and avert the danger” that threatened “to sweep into the gulf of destruction all that is good, to corrupt the youthful mind, pervert the nature of men, and overturn all the social, religious, and political landmarks, which distinguish civilization from barbarism, and Christianity from paganism.” Other supporters were more circumspect, yet saw the meeting as the last best chance to show a deeply suspicious South that the North favored the Compromise at a time when its opponents threatened to carry state and local elections.Footnote 44 Although the majority of those in attendance at Castle Garden were merchants, the main speakers were all lawyers. Much of what they had to say involved the merits of the Fugitive Slave Law. Neither trial by jury nor the denial of habeas corpus, they declared, was threatened by the law. James W. Gerard departed from the message, if only briefly, to declare that he was a lifelong Whig, but one who was willing to abandon his affiliation if the party did not purge its ranks of abolitionists. “My country first and party last,” he thundered. The meeting affirmed its commitment to see that the law was enforced and declared the Compromise a fair resolution of the difficulties facing the country. A “Union Safety Committee” was formed, made up of Whigs and Democrats, dedicated to ensuring that all aspects of the Compromise were permanent. The committee declared itself in favor of the formation of a Union party made up of Whigs and Democrats committed to the election of supporters of the Compromise.Footnote 45

Robert West, editor of the Journal of Commerce, had earlier proposed a new slate of candidates to contest the upcoming New York state elections even before the meeting had convened. One of the potential leaders of the new party was Daniel Webster, the former Whig senator from Massachusetts and now the secretary of state in the Fillmore administration, a man with ambitions to become president, but whose chances were damaged, apparently beyond repair, when he came out in favor of Henry Clay’s compromise motion in March 1850. Webster’s March speech in the Senate surprised and angered many in the North. After all, he had often stated his opposition to the expansion of slavery. Now, he insisted, the South had a “well-founded ground of complaint” against those who harbored and encouraged slaves to escape, and that Southerners had a right to a law that ensured the return of their runaway slaves. Meetings of irate constituents and former supporters were called in the weeks after the speech to condemn the turncoat. Rev. Samuel Ringgold Ward, a former slave, now the pastor of an all-white congregation in upstate New York, condemned Northern doughfaces such as Webster, who supported the new fugitive slave law and who pledged themselves “to lick up the spittle of the slaveocrats and swear it is delicious.”Footnote 46 Some of Ward’s listeners may have winced at such imagery, but it was one that captured their deep sense of betrayal. African Americans meeting in New York City and Boston in the days after Webster’s speech denounced him for his “recreancy to Freedom.” The man who had once been in the “advanced guard of liberty and humanity,” Rev. Samuel J. May, the abolitionist, lamented that he had gone over to the enemy. It would have been “better for him and the country,” May suggested, had Webster died twenty years earlier and so saved his good name.Footnote 47

Over the next few weeks, many of the potential leaders of the new party – senators such as Solomon Downs of Louisiana, Henry Foote of Mississippi, Lewis Cass of Michigan, Daniel Dickinson of New York and Howell Cobb, the Speaker of the House from Georgia – were feted by the Union Safety Committee. At a reception for Cass, Dickerson, and Cobb in late November, Cobb pointed out that Whigs who supported the Compromise had recently carried the elections in Georgia, a demonstration, he believed, of Southern commitment to the Union. Now, white Southerners were all looking to the North to carry out its obligations to the Compromise, especially the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law. Such expressions of solidarity, they hoped, would allay deep Southern suspicions of the North’s commitment to the Compromise. The maintenance and execution of the law, he insisted, was “necessary to the perpetuity of this great and glorious Union.”Footnote 48

By the end of November, James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald, came out in support of the proposed new national party because, he argued, the two established parties had conceded too much ground to abolitionists and had monopolized elections in Northern states. A new party, pledged to the Union as it is, he speculated, would be seen as a form of “reparations” for past wrongs towards the South. Webster had sent a letter to the Castle Green meeting praising those who were not slaves to the party and pledging to support the proposed new party “whose principles and practice” were best calculated “to uphold the Constitution and to perpetuate the glorious Union.” He reiterated his position at a reception in his honor organized by the Union Safety Committee.Footnote 49 But recent election results in Ohio, New Hampshire, and New York disappointed supporters of the proposed party. By the end of January 1851, the Herald announced the new party stillborn. The established parties, especially the Democrats, had gotten cold feet, the editor lamented. But as Michael Holt points out, Webster was still trying to pull together a Union party as late as summer 1851 as a base for his presidential ambitions. By June, however, even these plans had evaporated.Footnote 50

Plans for the new party may not have gone as hoped, but the Union Safety Committee continued its activities. It raised money to encourage ministers to preach in support of the Compromise, and especially the law, and to have these published and circulated widely. It is likely the committee turned to ministers as the best way to counter criticism of the law by church synods and conventions. City merchants contributed $25,000 to print and have copies of the sermons distributed. Copies were also sent to members of Congress. December 12, 1850, was set aside as a special day on which sermons supporting the “Peace Measures” were to be delivered. Several were given in New York City by “eminent divines” on the need to obey the law. Rev. Dr. Springs’s was typical. They were friends of the law, he declared, and did not wish to interfere in the domestic affairs of the South. While they welcomed “free colored men” to their “doors and charity,” they were obliged to turn their backs on fugitive slaves. Springs was happy to see that one effect of the law was the rapid disappearance of fugitive slaves from cities such as New York. They were all required to recognize the relationship between master and slave as it was guaranteed by the Constitution. Anyone who thought slavery was a sin and felt compelled to resist it was “a perjured man.” Springs announced he was neither a supporter of slavery nor emancipation, but he had no doubt that freeing the slaves would be dangerous to the peace and stability of the country and ruinous to the economy. The destruction of the island economies of the West Indies in the wake of emancipation was clear for all to see. The lesson to be drawn from places such as Jamaica was that emancipation should be neither sudden nor immediate. What slaveholders should do instead was make every effort to ameliorate the condition of their charges. Keep your slaves, he told slaveholders, but “treat them well and when you think you could do better for them let them go.” The permanence, “the honor, and the integrity” of the country, he concluded, should never be sacrificed for the protection of fugitive slaves.Footnote 51

In Boston, where a hundred-gun salute greeted word that the Compromise had been passed, the city’s mercantile and manufacturing interests gathered for what was described as a “constitutional meeting” a few days after the assembly at Castle Garden. George T. Curtis, a close political ally of Daniel Webster, organized it as the city was recovering from the excitement over the attempted recapture the Crafts. All of the speakers were drawn from the ranks of Webster’s supporters. The main speaker was Benjamin R. Curtis, the brother of the organizer, and a prominent lawyer soon to be elevated to the federal Supreme Court. Curtis condemned recent meetings that vowed to resist the law as well as threaten the lives of those who tried to enforce it. With George Thompson in mind, Curtis wondered if it was “fit and proper” for foreigners to intrude into the country’s affairs. Nationals such as Theodore Parker, the prominent Massachusetts divine who had been active in the defense of the Crafts, and who had dismissed the law as unconstitutional and “the warrant of misery,” were also openly defying the law and ought to be punished. Such breaches of the law were acts of revolution that must be confronted by the patriotic. Drawing on rising nativist sentiments, Curtis insisted that states had every right to pass laws to protect themselves. They had a right, for example, to limit the entry of immigrants, such as the Irish, who were “ground down by the oppression of England.” By the same token, states had endorsed the fugitive slave clause in the Constitution because it guaranteed “incalculable benefits.” This was an act of “self-preservation.” Runaways had “no right to be here. Our peace and safety they have no right to invade....Whatever natural rights they have, and I admit those natural rights to their fullest extent, this is not the soil on which to vindicate them. This is our soil – sacred to our peace – on which we intend to perform our promises.” Such arguments, as we will see in a later chapter, were the foundation on which Indiana and Illinois would build their policies of black exclusion. David Henshaw of Leicester, who could not attend the meeting but sent the customary letter of apology, expressed serious doubts about the capacity of blacks for civilization. After all, they had not progressed in three thousand years in Africa and had shown only limited improvement in the years of contacts with whites in the United States. He even wondered if God, in his inscrutability, meant slavery to be a state of “probation and preparation for the black race for higher political and social condition.” The meeting denounced disobedience to the law, and called for a cessation of agitation because it endangered the “peace and harmony of the Union.” Webster was delighted with the outcome of the meeting and suggested that organizers print fifty thousand copies of the speeches and resolutions for distribution in Washington, DC, and the South.Footnote 52

A few days earlier, a similar meeting was held in Philadelphia organized by Josiah Randall, a “conservative Whig,” at which the main speaker was George Mifflin Dallas, a Democrat and former vice president of the United States. Dallas followed a line typical of speakers at other Union meetings. He emphasized the need to obey the Fugitive Slave Law and to stifle the “alarming movement,” and the “lawless and criminal violence” of its opponents, who were bent on disrupting the government. They aimed to trample on the rights of “the whole people.” As such, they were guilty of what he guardedly called “moral treason.” Dallas seemed reluctant to go as far as Webster and others who considered any form of organized opposition to the law treasonous. Another speaker, Col. Page, was less circumspect: the fanaticism that drove opposition to the law was nothing more than a “black tide of treason.” Dallas believed, however, that the law was in “perfect harmony with the Constitution” and necessary for its maintenance. It was also just to fugitive slaves because it provided “protection of legal forms and hearing...and responsible officers to direct the arrest, to adjudicate upon the identity, and ultimately to supervise and authorize” their removal. Such protections would have come as a surprise to accused fugitives. But Dallas’ position was in keeping with those articulated by James Mason in the Senate and John Crittenden in his report to the president. Josiah Randall rounded out the cast of speakers by calling for the repeal of the state’s 1847 law, which banned the use of state prisons to hold runaway slaves, as the “most odious and unconstitutional measure,” and a form of nullification.Footnote 53

Almost simultaneously, an estimated two thousand attended a Union meeting in Manchester, New Hampshire, where speakers called on participants to stand by the “constitution as it is, and by [the] country as it is, one, united, and entire.” The country had just been brought through a dark period by wise men who had relied on compromise, one of its founding political principles, to effect an agreement. While they recognized the right of citizens to lobby for modifications of laws, no one had the right to resist their enforcement once enacted. The resolution supporting the law ran into some opposition from the floor but, in the end, was adopted. When a Rev. Ross, a Free Will Baptist minister, asked to be heard, he was denied; the meeting, he was told in no uncertain terms, was restricted to “citizens who were in favor of supporting the constitution and laws.” Over the succeeding months, meetings were held away from the East Coast and the mid-Atlantic, in places such as Belleville, in southwest Illinois, and in the small town of Elliottsville in northwest New York, close to the Pennsylvania state line. They addressed many of the same issues, but were less concerned to adopt Webster’s larger political agenda. There were also a scattering of smaller meetings in the Border South, in places such as St. Louis and Cape Girardeau, Missouri, whose agendas had less to do with the Fugitive Slave Law and more with the need to ensure the political survival of the Compromise as a whole.Footnote 54

If these Union meetings were meant to overwhelm opponents of the law and, simultaneously, reassure the South that those in the North who mattered were squarely behind all the measures of the Compromise, and none more so than the Fugitive Slave Law, then the organizers were to be disappointed. Supporters of the law were ridiculed, especially in black communities, which felt the full brunt of the law’s mandates. Jermain Loguen spoke for many in these communities when he dismissed supporters and operatives of the law as “pimps of power.” Opposition meetings, especially those organized by African Americans, pledged to resist violently any effort to enforce the law. As early as April 1850, Samuel Ringgold Ward set the standard of defiance when he called on his listeners in Boston to make enforcement the “last act in the drama of a slave-catcher’s life.” It was better for the slave catcher if he made peace with his God before he came into Ward’s home. At the second opposition meeting in Pittsburgh, Martin Delany spoke for many: “My house is my castle; in that castle are none but my wife and my children, as free as angels of heaven, and whose liberty is as sacred as the pillars of God. If any man approaches that house in search of a slave... if he crosses the threshold of my door, and I do not lay him a lifeless corpse at my feet, I hope the grave may refuse my body a resting place, and righteous Heaven my spirit. O, no! He cannot enter that house and we both live.” This commitment of defiance struck a responsive chord with many in Northern communities. Henry Bibb, who had escaped slavery in Kentucky, employed more lofty reasoning, but to the same effect, in a speech in Boston: Death was preferable to a return to slavery. The act of escape, he argued, restored a “portion of lost rights,” particularly the right to self-defense, which slavery had usurped. The law and the declarations of African American defiance also pushed some white abolitionists to abandon their principled commitment to nonviolence. Henry C. Wright, a Garrisonian abolitionist, and long a leading proponent of peaceful resistance to slavery, for instance, told a Cleveland, Ohio, meeting that, if he were a fugitive slave he would not hesitate “to plunge a knife into the heart of his pursuer” before he would allow himself to be taken back. An individual known only as “Seth” of Syracuse, New York, captured the promise of violence in verse:

There were abolitionists who worried over what they saw as an unmistakable drift to violence. The movement’s chances of success, they believed, were predicated on an unwavering commitment to nonviolent resistance. Gamaliel Bailey, editor of the National Era, who had experienced the anger of anti-abolitionists mobs in both Cincinnati and Washington, DC, spoke for many worried about calls to resist the law violently. If good men, he wrote in the wake of the rescue of the Crafts, “undertake to nullify bad laws by force, bad men will be encouraged to nullify good laws by force. It will never do to recognize the principle of Lynch law in a law-abiding community.” If one chose to disobey any law, one must be prepared to accept the consequences. That may be so, many responded, but what Congress had done was enact a law that was morally indefensible, one which flew in the face of traditional legal rights and traditions. William Jay, a New York abolitionist, was even more explicit than Bailey. While he was not opposed to violence in principle, the death of a slave catcher, he wrote a group of black New Yorkers, would be considered murder, not civil disobedience. Violent responses to “kidnappers” were both unnecessary and “morally wrong” and, he predicted, would “prove to be the source of great evil” to the black community. Resistance of this sort would lead inevitably to counterviolence by “Southern ruffians and their Northern mercenaries.” Jay had no doubt that the law would result ultimately in bloodshed, but when it did, he pleaded, “let it be the blood of the innocent, not of the guilty.” If anything could rouse “the torpid conscience of the north,” it would be “our streets stained with human blood, shed by slave-catchers.” Jay’s pleas fell on deaf ears; as Ward and the others promised, the blood in the streets would not be theirs. But Bailey’s and Jay’s worries were largely misplaced. In the heat of the dispute over the law, black communities were practical, if not always rational, when it came to dealing with slave catchers. Henry E. Peck spoke for many: the type of resistance employed had to be tailored to what Peck, writing from Rochester, New York, called the “character of the wrong” and the circumstances in which it occurred. In some instances, passive resistance was appropriate, in others, noncompliance, and in yet others, violence.Footnote 56 This approach gained some traction as the forms of resistance to the law evolved over the course of the decade.

These early and frequently repeated declarations of resistance, violent or otherwise, set the background to a widespread and often heated debate in the North over the meaning and significance of the law. Not surprisingly, local newspapers drove as well as reported on the debate. As a rule, the partisan affiliation of a newspaper largely determined the position it took. But the Compromise, and especially the Fugitive Slave Law, did complicate these responses. Those with Whig proclivities divided depending on whether they supported the Fillmore administration or the president’s opponents in the party, such as William Seward. Democratic newspapers were also divided over the issue. Those who supported Ben Wade, Salmon Chase, and Joshua Giddings and the Free Democrats in Ohio and elsewhere, staunch opponents of slavery, took positions diametrically opposed to those who toed the conventional Democrat line.