During the Vietnam War, Vietnamese women acted in pivotal roles on every side of the conflict. They served the war effort as politicians, soldiers, diplomats, covert agents, employees, and active civilian voices. They shaped foreign relations through their encounters with foreign men as friends, lovers, and wives. The line between civilian and combatant blurred throughout the war and in the decades since, causing inconsistency in how or if women have been addressed in relation to the war. The absence of their stories from the narrative of Vietnam War history left a noticeable gap that many scholars have sought to recover in recent years. The contributions of women are best understood when read as a part of the larger war. Women did not live and work in a vacuum detached from the conflict. For some, their drive to participate in the conflict began long before American escalation, rooted in the colonial and revolutionary history of Vietnam during the first half of the twentieth century. Others found themselves tied to the war for pragmatic reasons. Regardless of motivation, Vietnamese women, both on and behind the lines of combat, represent critical figures in the framing of the conflict.

The accounts in this overview focus largely on events that occurred between the fall of the French colonial government in 1954 and the fall of Saigon in 1975. The division of Vietnam along the 17th parallel and the subsequent increase in American support for the government of Ngô Đình Diệm in the South led the two territories to approach women’s involvement in different ways. Tracing how gender norms in Vietnam changed at the outbreak of the war brings the roles of women during the conflict into sharper focus. In the North, women worked actively and openly in military squadrons, on recovery and medical teams, and as diplomatic agents. Soldiers trained in co-ed units, with women taking part in grueling jungle warfare and serving in units sent to retrieve bodies or lay mines. The consequences on women’s bodies of working in swamps and jungle conditions had lifelong impacts that led to birth defects, infertility, and struggles with disease caused by poisoning from Agent Orange and other toxins. Laws sought to define and preserve traditional ideals of marriage and the family. The involvement of diplomatic women such as the foreign minister of the National Liberation Front (NLF), Madame Nguyễn Thị Bình, helped forge the Paris Peace Negotiations.

In the South, American soldiers stereotyped Vietnamese women as prostitutes, hooch maids, and/or NLF spies. These women certainly existed, and not in small numbers, but these beacons of popular memory hardly tell the whole story. The Ngô Đình Diệm government passed laws prior to escalation to limit immoral behaviors in an attempt to reduce negative images of the South. Following the ouster of Diệm and American escalation, many women legally worked in war industries and helped with the logistical needs of the US military forces through the cities. As most troops stayed behind the frontlines, their operations required considerable upkeep. The laundry, cooking, cleaning, and entertainment industries flourished. The South Vietnamese economy was crushed under wartime inflation brought on by thousands of GIs arriving each month beginning in 1965. New bars and restaurants catering to Americans opened their doors and saw a period of relative prosperity in the early years of escalation. Marriages between foreign soldiers and civilian women troubled both governments, which sought to limit such unions and any mass exodus that might be related. As the war expanded, accounts of rape also increased, driving antiwar protests. To keep morale high and open new avenues of opportunity for Southern women, American female service members participated in the formation of a South Vietnamese Women’s Army Corps (WAC).

Women operated with great agency during the war, dictating not only the actions of nonstate actors, but also military movements and diplomacy. In both the North and the South, women who remained behind the lines took on the responsibilities of earning necessary income while acting as fulltime caregivers for their families. Those outside government and military work who engaged in personal relationships with soldiers drove nations to change laws and frustrated foreign policy. Antiwar groups adopted imagery of the treatment of women by foreign soldiers to use as a powerful tool in their efforts to end the conflict. In recent years, scholars have begun to acknowledge the critical roles of women in shaping the conflict on both sides. This chapter briefly highlights that scholarship and the key ways that women participated in, and dictated the actions of foreign governments during, the Vietnam War.

North Vietnamese Women

In North Vietnam, more women took on overtly militant roles than women in the South. From actual military training to body recovery, the North utilized women in and around combat operations. In addition to military positions, Northern women also actively participated in diplomatic efforts. Karen Gottschang Turner and Phan Thanh Hao’s 1998 classic Even the Women Must Fight: Memories of War from North Vietnam shared some of the first accounts of North Vietnamese women’s experiences with global audiences. Based on years of research and interviews with female veterans, their research provided glimpses into the lives of Northern soldiers, militiawomen, and volunteer youth, among others. Through their interviews and accounts, Turner and Hao illustrate the vital importance of Northern women to the communist war effort.Footnote 1

Communist activists viewed female participation in the war as essential to victory. While women volunteered for service in large numbers, their acknowledgment from men or the party came slower than many would have liked. As the party began to acknowledge the accomplishments of women as soldiers and heroines of the communist cause, they also told male forces that old ways of thinking about women distracted from their potential to support the war effort. Rather than keeping women in subservient roles, all Vietnamese should encourage them to pursue membership and volunteer for war work. Between 1965 and 1969, Turner and Hao write, the number of Northern women working increased from 170,000 to 500,000, with many taking jobs to support the war effort.Footnote 2 As with other conflicts, women took on more positions in industry and agriculture to maintain the needs of the military and keep the nation functioning during the war.

Many women in North Vietnam, regardless of their role in the war effort, underwent some form of training in military tactics. Those serving in the militias received training similar to male soldiers, and efforts to draw women into military services were also codified by the North Vietnamese constitution.Footnote 3 The programs involved marching with loaded packs, using weapons, and remaining covert in their movements to prepare for the difficulties of life in the mountainous regions of Central Vietnam and along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. The lack of proper sanitation and dietary supplies created additional challenges for women working in militias, leading many to struggle with their menstrual cycles. While not deployed as part of regular ground combat units, female guerrillas took on nearly every other available task including operating anti-aircraft guns. In addition, they traveled with units to work as engineers, liaisons, and sappers to keep units moving forward.Footnote 4 Beyond the segregation of frontline soldiers, women volunteered for and participated in all other aspects of military life. As Turner and Hao show in their study, however, their presence did not necessarily mean acceptance. Even women known as military heroines faced negative backlash for their actions as society adjusted to the presence of women in roles traditionally associated with masculinity.

Members of organizations such as the Youth Shock Brigades faced extreme conditions related to weather, animal predators, and military bombings. The Brigades, functioning from 1950 to 1975, recruited patriotic young people to participate in support operations including the movement of supplies, clearing or rebuilding of roads, and identification of bomb and mine locations.Footnote 5 Scarce supplies and harsh conditions left many members who survived their service with permanent bodily damage. Women suffered injury, mutilation, and infertility because of their work along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. Others experienced rape and sexual assault at the hands of their fellow soldiers in the field. These challenges did not stall recruitment, however. Women actively participated alongside men in volunteer operations like the Brigades throughout the war.

Women also took on roles as medical professionals, aiding with war casualties in the South. Đặng Thùy Trâm served as a doctor in the Quảng Ngãi province of central Vietnam. She traveled from Hanoi to arrive at her clinic in 1967. Thùy Trâm’s diary, recovered by an American soldier after she was killed, details her treatment of soldiers, her dedication to the party, the treatment she received from others in the resistance who considered her too bourgeois, and the conditions of war including the role of Agent Orange.Footnote 6 Thùy’s account as a well-educated female physician offers a different perspective from many in the Youth Shock Brigades, but their experiences with death, sickness, and the destruction caused by defoliants and bombings share many similarities.

Vietnamese women also took on active political roles on the diplomatic side of the conflict. Most notably, Madame Nguyễn Thị Bình, a Southerner, served as the foreign minister for the National Liberation Front’s Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG). In her position as head diplomat for the PRG, Madame Bình took a stance against South Vietnam to promote a revolutionary communist government in its place and remove Americans from the nation. While not directly representing North Vietnam, their eager support of her participation in the negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference highlights the importance of women at the highest levels of North Vietnamese government. As foreign minister, Madame Bình traveled extensively to support the cause and build a public face for female diplomats working against South Vietnam and its Western allies. She notably won support from the Nonalignment Movement in 1970 for the PRG’s cause. Months later, historian Lien-Hang T. Nguyen argues, her status at the Paris Peace Talks took on even more significance as she published an eight-point plan that served as a buffer in negotiations between North Vietnam and the Americans. The efforts of Madame Bình, as a leader and member of numerous women’s and revolutionary groups, illustrate the influence of female diplomats, to whom she referred as “soldiers with long hair,” in the Vietnam era.Footnote 7

Not all North Vietnamese women supported the war effort, however. Antiwar activists in the North challenged the efforts put into place by Hồ Chí Minh and First Secretary Lê Duẩn. The Women’s Union of North Vietnam worked across international borders to promote peace, building on what Judy Tzu-Chun Wu has called “a belief in global sisterhood, projecting and cultivating a female universalism that simultaneously critiqued and transcended racial and cultural divides.”Footnote 8 For years, along with female activists from South Vietnam and Western nations, the Women’s Union of North Vietnam participated in various conferences to promote peace. The topics tended to focus on the importance of family preservation and covered issues ranging from racial injustice to ending nuclear weapons programs. The conferences reached their height with the 1971 International Women’s Congress. The program combined fights for women’s rights with the peace movement. Wu proves in her work that Vietnamese women did not simply adopt the ideologies of Western female peace activists, but helped to form and shape the movement through their views toward female unity.

In their personal lives, North Vietnamese women faced similar laws and restrictions on family and domestic status as women in the South. Universal concerns over the fate of their children and families dictated the actions of many women related to how they approached their marriage or their stance on the war. New legislation meant to protect family values shifted previous views on marriages based on which men would occasionally take more than one wife. The National Assembly’s Family Decree passed laws limiting marriage to only one spouse. The laws placed stigmas on second wives, like Lê Duẩn’s wife Nga, who was raised in the South and moved north with their children as concern grew over the outbreak of war. Despite her revolutionary training and relationship with Lê Duẩn, members of his first family and the Women’s Union treated Nga poorly because of her status as a second wife, forcing her first out of the country and then back to the South.Footnote 9 Although not everyone followed the laws, marriages in North Vietnam tended to remain more traditional longer than in the South, where the influx of foreigners created more opportunities to marry outside villages and against family wishes.

The war shaped the experiences of North Vietnamese women by placing an emphasis on a patriotic and communist duty to the state. The prevalence of women in or near combat operations distinguished them from Southern women, who still saw war on a daily basis, but rarely took up arms in the same way. Women flourished in militia, agricultural, and industrial service, but often suffered physically because of poor working and living conditions and a lack of supplies. Their efforts helped to reshape traditional views of women as inferior for some observers, although others continued to resist the implementation of women in military and party leadership positions. Diplomats and activists also thrived in the North, with many promoting the roles of women as critical to winning either the war or the peace.

South Vietnamese Women

Within the borders of South Vietnam, women took on complicated and dynamic roles. The proximity to foreign soldiers created unique social challenges and raised speculation about women who interacted with foreigners. Even ahead of military escalation of the conflict, the American-supported Diệm government worked to restrict the behavior of its citizens both politically and socially. Despite these efforts, the 1963 coup against Diệm and the arrival of thousands of foreign soldiers starting in 1965 derailed the possibility of maintaining a society free of industries that were perceived as immoral, such as prostitution. The war drove young women into the cities in large numbers where they struggled to find work, leading many to rely on the war economy for income. Outside clandestine activities such as sex work and participation in the shadow economy, many Southern women took administrative or service jobs in government. In some instances, their roles made them vulnerable to attack or manipulation. Political repression of former Việt Minh revolutionaries and negative perceptions of Americans contributed to the rise of the NLF which fought in the name of the PRG. As has been noted, Southern women took on significant leadership roles in the organization. They directed military operations and served as political negotiators. Historian Patricia D. Norland’s work traces the interest in politics starting during the colonial era, with privileged women embracing left-leaning education at high rates starting in the 1940s.Footnote 10 Women sympathetic to the Southern cause could also join military ranks in the Vietnamese Women’s Army Corps, but mostly served in administrative roles and received considerably less military training than their Northern counterparts. The presence of foreign soldiers in South Vietnam created unique challenges not seen in the North and resulted in the allies spending considerable time negotiating appropriate social relations that kept their fighting forces ready while maintaining a positive image for their respective countries.

Within South Vietnam, the social and political changes triggered by the war altered societal norms. Prior to American escalation, the new government of the Republic of Vietnam that ousted Emperor Bảo Đại worked with US advisors to forge a new government and a security strategy. Unmarried, the newly named president of South Vietnam, Diệm, paired with his brother’s wife (Trần Lệ Xuân, known widely as Madame Nhu) to serve as his nominal first lady. Much of South Vietnam’s social behavior and legal treatment of women arose from laws passed under pressure from Diệm and Madame Nhu. Her policies, mostly guided by the family’s Catholicism and remembered for an unpopular ban on dancing, meant to empower South Vietnamese women by offering them more financial independence and restricting practices that might lead them to sex work.

Despite their role in aiding her family’s ascension to power, Nhu used her power in Diệm’s administration to focus attention on American visitors and military personnel who she felt brought negative values to South Vietnam that distracted the people from the conflict and nation-building. Nhu’s talking points centered on raising awareness of women’s issues, redefining morality laws, and fortifying South Vietnam’s image on the world’s stage. Yet bans on divorce, adultery, and vice activities all but criminalized women. Still, many found a voice within South Vietnam. Whether women supported the Americans or not, protests and fundraisers pushed them into the war’s discourse. In the wake of the war, women suffered for their participation in the South. Reeducation camps violently punished women for associations real or imagined. War widows and mothers of Amerasian children, those born from unions between American soldiers and South Vietnamese women, struggled to survive in the postwar world. Their involvement shaped the direction of policy discourse and made day-to-day life on military bases possible.

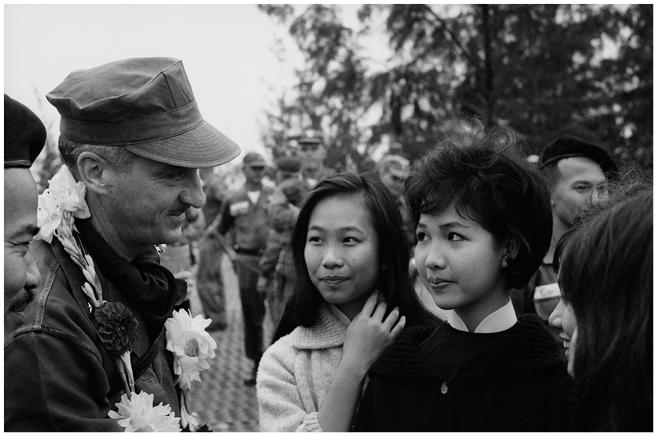

Figure 10.1 US brigadier general F. J. Karch is greeted by Vietnamese women in Đà Nẵng (March 8, 1965).

Before mass US escalation began, Diệm and Madame Nhu enacted two pieces of legislation anchored in their Catholic faith that targeted what they saw as immoral social behavior. The 1959 Code of the Family and the 1962 Laws for the Protection of Morality shaped social relations and made widespread wartime practices such as prostitution and cohabitation illegal. The legal brothel culture under earlier French leadership during the French Indochina War contributed to Vietnamese attitudes of Western men and their expectations of Vietnamese women.Footnote 11 The perception of men seeking out Vietnamese companionship strictly for sex threatened the reputation of any women who engaged with foreigners. While Nhu herself pitched her programs as forms of altruistic religious piety and forward-thinking feminism, historians have illustrated that many of them provided personal benefits for Nhu. Most notably, the first lady pushed for legislation to ban divorce. In creating stricter family laws and opening pathways for women’s rights, she prevented her husband from divorcing her and guaranteed her position in government.Footnote 12 Nhu took her role in government seriously. She even openly challenged American officials on their behavior and the risks presented by their interactions with Vietnamese women.Footnote 13

The Code of the Family offered legislative changes that encouraged independence for married and widowed women.Footnote 14 New programs to benefit women’s rights included property-ownership laws that allowed women to take sole possession of homes or land. With the changes in property laws, women no longer needed to rely on a male relative like a husband or father to retain a home in the case of separation or death. The “marriage property system” of the code encouraged couples to outline their property rights in a process similar to a prenuptial agreement. In theory, the change made men and women equal in economic status. The passage of legislation failed to create drastic change overnight, however, and many continued to view women as subservient to their husbands despite the changes. Still, over the course of the decade, women began to see more options for employment and economic freedom opening to them.Footnote 15

Like the Family Codes, the 1962 morality codes targeted behavior deemed immoral or damaging to the global perception of Vietnamese culture and especially of Vietnamese women. Among other things, they banned prostitution, gambling, pornography, beauty contests, sentimental songs, and dancing. In a region largely influenced by Western culture from decades of living with both the French and the American presence, the restrictions felt antiquated to many. The laws mainly targeted young women who worked for, solicited to, or dated foreign men in the cities of South Vietnam. Nhu’s laws were not universally popular among political figures in the South, either. Some feared they might alienate an already struggling sector of the population, tempting them to support the NLF, while others simply viewed the policies as outmoded or too difficult to enforce. Likely, many saw little wrong with the prostitution industry, which catered to both local and foreign audiences.Footnote 16 As more Americans descended on Saigon and other Vietnamese cities, police struggled to limit the banned behaviors. After Diệm’s death, only prostitution remained a real concern for South Vietnamese leadership.

Following escalation, women in the South found multiple entries into the war economy. They served with the South Vietnamese Women’s Army Corps, worked for Americans in clubs or offices, sold goods and sodas on the streets, or engaged in black-market trade, while others sold their bodies as part of the burgeoning sex trade.Footnote 17 Some women and girls – not all of those working for Americans had reached adulthood – profited from the freedom and the easy-spending American soldiers. Brothels recruited or coerced workers in diverse ways. In historian Mai Lan Gustafsson’s oral history research, several women later told her that the war had been “the best time” of their lives.Footnote 18 In addition to their ability to gain more income in the cities than they might otherwise have made in their villages, the relative freedom of living in Saigon or other cities offered an opportunity to achieve independence at a young age.

For women seeking active military participation, the South Vietnamese WAC offered an opportunity for uniformed service. American women who traveled to Vietnam as part of the US WAC took part in the training of Vietnamese women for their own military units. Lieutenant Colonel Judith Bennett of the US WAC recorded an interview about this training in 1966, laying out the similarities and differences between the approaches of the two nations regarding the duties of their female members. Both South Vietnam and the United States relied on volunteers to staff the WAC forces. South Vietnam limited women, unlike their Northern counterparts, to administrative roles to free up more men to deploy for combat. Part of the requirements for Vietnamese women included English-language skills to serve in the officer corps so they could work closely with American forces.Footnote 19 Tasks for the Vietnamese WAC personnel also involved caring for the dependants of soldiers, participating in “revolutionary development” units to help stabilize insecure areas, and as police officers.Footnote 20 Started in January 1965, the Vietnamese WAC units organized as escalation began in the South. While prohibited from serving in combat, WACs participated in other ways that made them a vital part of the larger war effort.

The highly visible nature of the prostitution industry in South Vietnam overshadowed the work conducted by women serving in legal occupations like the WAC. The industry’s scope created challenges for mediating the impact on the perception of Vietnamese women, foreign relations, and public health.Footnote 21 Considered by many in the military as a natural byproduct of war, prostitution created real challenges for military–civilian relations and the local economy. While American leadership hoped to simply minimize the damage, South Vietnam ostensibly worked toward an eradication policy to eliminate the industry all together. A South Vietnamese “Seminar on the Eradication of Prostitution” singled out Americans as the main source of the problem, and identified bars and brothels known to cater to foreigners. Frustrated with the lack of results from eradication programs, panelists assessed that the policies encouraged bar- and brothel-owners to hide the illicit side of their industries.Footnote 22

Eradication policies and the continued increase in prostitution led to a public health crisis, since officials provided no education or treatment related to safe sex, and Diệm-era antiprophylactic laws banned contraception. Attempts to screen and treat Vietnamese women by American and NGO hospitals showed that roughly half of those seen tested positive for venereal disease, an unsurprising number since 62 percent had told staff that they did not use any form of prophylactics while working. Further exacerbating this issue was that formal education, including any sex education or knowledge of diseases, was severely lacking.Footnote 23 Like all aspects of society, the quality of health care and knowledge also depended on the type of establishment the women worked in. From exclusive members-only brothels to women who peddled in the streets, the experiences for prostitutes varied widely.

Prostitution was only one part of the black market that threatened the economy in South Vietnam, which was already damaged by inflation. With their close access to Americans while working on military posts, women had a unique opportunity to obtain and sell black-market goods. As Helen Pho has argued, the black-market economy in the South weakened the nation’s ability to govern. The flow of Military Payment Certificates (MPCs) in and out of Vietnamese hands broke military laws and helped the market to flourish. Bar girls and other service industry employees accepted the currency and used it to purchase other black-market items. Through the buying and selling of goods ranging from air conditioners to hair spray, the black market cost both governments millions of dollars.Footnote 24

One of the most abused products on the black market was money itself. Soldiers paid housekeepers, peddlers, and prostitutes in both American dollars and nonconvertible MPCs. Civilian women enjoyed unprecedented access to jobs with the US military during the war, working for low wages that made it impossible for American contractors to compete. Women used their connections with Americans to purchase and trade in foreign goods that could earn them significant profits with local consumers. Violating policies regarding the use of MPCs constituted one of the most common ways American military police could apprehend Vietnamese women, although they turned them over to local authorities. The benefits of working in the black market outweighed the risks of arrest, however, since American goods drew a high profit. The impact of this trade on the economy triggered inflation in an already struggling economy.

The proximity to men that arose from working within American bases placed women at risk of sexual assault. The lack of publicity and accountability for attacks heightened the risk. Soldiers on all sides of the conflict perpetrated attacks, including rape, against South Vietnamese women both on and off the frontlines of conflict. The existing literature focuses on the role of American soldiers, but Vietnamese and South Korean troops perpetrated numerous acts of rape and assault as well. Nick Turse argues that American soldiers conducted rape as part of their strategic operations and following systematic orders to “kill anything that moves.”Footnote 25 Turse’s work sparked considerable debate related to the concept of the violence as systematic and indiscriminate. The nature of sexual violence in Vietnam cannot be summed up that simply. In Europe during and after World War II, as Mary Louise Roberts illustrates, there were patterns or “waves” in rapes in which soldiers perpetrated more crimes than they had in other eras.Footnote 26 Attacks in Vietnam also differed dramatically depending on the location inside or outside cities, the year they took place, or the relationship with the perpetrators.

Within South Vietnamese cities, accounts of rape received considerably less reporting in American media sources, despite accusations starting with the escalation in the number of US troops in 1965.Footnote 27 As more foreign troops flooded into cities, crime and violence increased. The economic and political costs of the disruption caused by soldiers forced the US military to relocate soldiers to a post outside Saigon at a massive facility by Long Bình. The army hired local women to take on service tasks including laundry and cleaning with reasonable salaries, but placed them in vulnerable power positions within the American compound. Reports of assaults indicated that some took advantage of their proximity to female employees to coerce or rape the women.Footnote 28

Outside military installations, attacks in bars and other public places also indicate the risk of violence against women that took place in the rear echelon of combat more than scholars tend to acknowledge. Local papers carried the reports, and military police blotter records pointed to accusations of assault and rape. Most of the reports link the attacks with alcohol use. Encounters between Vietnamese women and soldiers happened most frequently in bars or brothels catering to foreign troops. In some cases, military police noted that they simply let an accused soldier sleep off his hangover before sending him back to his posts.Footnote 29 The typically one-off attacks in the cities failed to garner the same international attention as massacres in villages like Mỹ Lai due to scope, but their existence contributed to a negative perception of foreign soldiers for some in Vietnam. Scholars dispute the number of assaults and the chain of responsibility for rapes, with both difficult to pin down as surviving victims found few friendly audiences to whom to voice their complaints.

Women who bore the children of American servicemen faced stigmatization, and children suffered from harassment. Orphanage numbers swelled considerably during the war, with the number of Amerasian orphans reaching between 25,000 and 50,000.Footnote 30 As the war lingered for a decade with consensual and nonconsensual intercultural relations persisting at high rates, an orphan crisis sparked international attention. The 1987 Amerasian Homecoming Act sought to create opportunities for those left behind, including children of rape, and brought more than 21,000 children fathered by American soldiers to the United States. Still, far more remained in Vietnam. The victims and children of South Korean troops, in contrast, continue to fight for reparations for war crimes including rape.Footnote 31

The violence of the war’s battles coupled with the photographic evidence at massacre sites like Mỹ Lai that showed the targeting of women and children only added to the negative perception within antiwar communities. Vietnamese women’s marches highlighted the violence as one of their central themes. One member of an anti-American group recalled the story of the rape and murder of a pregnant woman as her motivation to take to the streets. She reflected, “as a woman and a peasant in the South, I only worked very hard to live. When I witnessed the savage crimes of GI’s [sic] with my own eyes I felt very strongly. In order to defend my own life and the lives of my family, I had no other way but to join other women and to fight back.”Footnote 32 Women’s participation in antiwar or anti-South Vietnamese protests began before escalation, as shown by Norland’s work on South Vietnamese elite women,Footnote 33 but participation fluctuated in response to the war and the behavior of troops.

South Vietnamese women who participated in communist activities, or otherwise sympathized with the North, also took on powerful leadership roles in the NLF to support the PRG. Nguyễn Thị Định organized the 1960 uprising in Bến Tre province to oppose the Diệm regime in the South. During the 1950s, Diệm targeted former members of the Việt Minh using financial penalties, reeducation camps, torture, and murder. This treatment and proximity to revolutionary forces in villages motivated many young women to support the communists.Footnote 34 Nguyễn Thị Định’s success at Bến Tre made her one of the foremost female members of the NLF. Part of the strategy for women’s roles in the Front played on traditional perceptions of women as weaker or unassuming figures in society. By taking the central role in public protests, Mai Elliott argues, women who marched on local leadership to present complaints typically received less harassment from the South Vietnamese government and military. The rallies and marches attracted large audiences, and officials feared the public might perceive them as weak or cowardly if they attacked or arrested large groups of female revolutionaries.Footnote 35

Following Bến Tre, Nguyễn Thị Định rose quickly through the political ranks. In 1964, she was elected as a leader to several party and women’s organizations, including the post of chair of the South Vietnam Women’s Liberation Association. The following year, the South Vietnam Liberation Armed Forces named her deputy commander.Footnote 36 Women such as Madame Bình and Nguyễn Thị Định represented the political elite, but their roles resonated with their female counterparts through appeals to families and their desire for security. Beyond Vietnam, members of the NLF also appealed to women abroad, particularly in the United States, to help them in their efforts by pressuring for an end to the war at home. Outside political and diplomatic roles, NLF women also took on more militant roles. They received less publicity than their counterparts in the North, but stories of armed female heroism helped fuel propaganda campaigns and encouraged Southern women to join resistance movements.Footnote 37

Not all encounters between American soldiers and South Vietnamese women were negative, however. Couples met and fell in love. They courted in the cities and fought for the right to marry in the face of skepticism from parties on both sides. GI–civilian dating and marriage applications faced scrutiny from families and governments alike. South Vietnamese police harassed women who openly dated American men, accusing them of prostitution to win bribes. American officials worried whether girlfriends and brides held genuine feelings for their partners, or if they were entering the relationships simply for monetary gain, a way out of Vietnam, or even to obtain intelligence as a spy. Regardless of the hassles they faced, many couples successfully navigated the difficult process to remain together.

Developments in how the South Vietnamese government managed intercultural relationships between South Vietnamese women and foreign men created confusion about appropriate legal behavior.Footnote 38 Despite ending enforcement of several of the laws, like those against dancing, South Vietnamese leadership remained critical of the social institutions where interracial relationships bloomed.Footnote 39 To discourage the relationships, South Vietnamese police targeted women as they traveled with American soldiers and threatened their reputations if they failed to produce “cohabitation certificates” or pay off the officers. The harassment grew so prevalent that the Capital National Police Command in Saigon issued instructions warning their police officers against the behavior. In 1972, the American Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) shared the release with their soldiers to warn them against paying the bribes or applying for any requested licensing. The permissive nature of the relationships pressured governments to stop requiring the often-requested “cohabitation certificates” for dating, living together, or traveling together on public transportation. This applied even if the woman in question did work in prostitution.Footnote 40

Couples pursuing serious relationships struggled to formalize their unions through marriage. The United States approved more than 8,000 marriages for soldiers during the war, far fewer than during the wars or occupations following World War II or the Korean War.Footnote 41 The frequency of encounters between soldiers and civilians cannot explain this change; rather a shift in Cold War mentality and immigration laws serve as better explanations. By the start of escalation, military brides no longer qualified for war-bride status that prioritized their entry into the United States. The 1965 Hart–Celler Immigration and Nationality Act focused on existing family reunification rather than “race-based policies” that prioritized or limited specific nationalities.Footnote 42 With this shift, the military instituted a long and detailed process that discouraged soldiers from completing them. As the war came to an end, the emphasis on family reunification prompted relatives of those who had successfully navigated the system to use their connections to leave Vietnam for the United States.Footnote 43

In the 1950s, the Diệm administration had opened the possibility to the foreign unions by dissolving the focus on prearranged marriage and allowing for marriages chosen by the participants on the grounds of love. Rates of arranged marriages fell quickly, but filial loyalty encouraged many young women to seek the permission of their family before selecting a husband of whom they might disapprove. Over time, fewer parents arranged marriages for their daughters. Instead, and with the intention of both protecting girls and young women by removing them from rural wartorn villages and finding a source of income for families, many opted to send their daughters to the cities. Even families who hoped their daughters would marry a man of the family’s choice found those men absent during the conflict. For the United States, concerns that the women might work as spies or quickly divorce their husbands once they immigrated represented some of the main apprehensions for Americans, while the Vietnamese government worried about how women fleeing the nation to marry Americans reflected national morality. For those who simply fell in love and hoped to remain united after the war, the hurdles of the marriage policies marked a worthwhile frustration. As with many other policies, the view of wives as the ones who placed both nations at risk reflected the broader suspicions of South Vietnamese women and their relationships with foreign men.

As living legacies of soldier–civilian sexual encounters, Amerasian children played a significant role in the postwar era. Numbers of possible orphaned children are estimated as high as 879,000, although some scholars place the number around 50,000.Footnote 44 Efforts to get children out of Vietnam, either as orphans or simply for their own safety, resulted in a rise in adoption requests spurred by groups in Australia, Europe, and the United States. Humanitarian evacuations, like Operation Babylift, and adoption politics faced challenges in the years surrounding the fall of Saigon in 1975, often overlapping with the ongoing refugee crisis.Footnote 45

Conclusion

The encompassing realities of war in both North and South Vietnam meant that few, if any, women remained outside the conflict. From military and industrial roles to diplomatic and protest efforts, women helped drive and shape the day-to-day outcome of battles and negotiations. Their personal lives took on political meaning as governments sought to control their sexual behavior and determine the legal limits of their marriages. After the American military forces left, Southern women who had interacted with the foreign military faced reeducation and scorn for their past actions. Many struggled to maintain employment, and those with Amerasian children struggled to protect them. Regardless of their roles in the war, Vietnamese women found ways to survive. Their actions are often discussed, as they are in this chapter, in isolation from the broader conversation on the war. In reality, women’s participation – from the highest levels of political figures to the lowest levels of nonstate actors – influenced the conflict as much as did that of their male counterparts. As their contributions are further engaged in the historiography, the significance of studying the war as an event that fully engaged soldiers and civilians across the region will allow historians to tell a more complete story.