The first and greatest challenge that any biographer of Hồ Chí Minh must face is the enormous mythology that surrounds the man. Because Hồ Chí Minh had a personality that both his supporters and his adversaries found appealing, the outlines of this mythology appeared early in his life and career, even before his emergence on the global stage. In the decades after 1945, this mythology was transformed into an elaborate personality cult, fashioned by the Vietnamese Communist Party and by Hồ Chí Minh himself. It is striking that Hồ Chí Minh is primarily celebrated today as the “Father of the Vietnamese Nation” (Cha già của Dân tộc Việt Nam); his role as the founder of the party receives considerably less attention, and his status as an agent of the Comintern during the 1920s and 1930s is hardly discussed at all.Footnote 1

Since Hồ Chí Minh’s death in 1969, his standing as a cult figure has grown to supernatural dimensions. In Vietnam today, he is often revered as a “tutelary genius” (thần) and as a figure who continues to “protect and nurture the people” (cứu dân độ thế). In the era of religious revival that has prevailed in Vietnam since the Đổi mới reforms, the number of shrines and temples dedicated to “Uncle Ho” grows ever larger.Footnote 2 In both official and popular forms of commemoration, Hồ Chí Minh has been integrated into the national pantheon and the longue durée of Vietnamese history.

But this apotheosis was not inevitable. Although Hồ Chí Minh played a central role in the founding and early history of the Vietnamese Communist Party, he served as the party’s general secretary for only three years. Given the enormous power that is typically wielded by general secretaries – both in Vietnam and in other communist states – Hồ Chí Minh’s relatively brief tenure in this role is significant. The contrast with the career of Lê Duẩn, who was elevated to general secretary in 1960 and held the position until his death in 1986, is especially remarkable. Despite what his propagandists and acolytes continue to insist, the early life and career of Hồ Chí Minh was not foreordained to be a voie royale that would carry him from Moscow to Hanoi, or from aspiring revolutionary to the presidency of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN).Footnote 3

Anticolonialism, Socialism, and the Making of a Pragmatic Revolutionary

When the future Hồ Chí Minh was still a teenager living in his native province of Nghệ An, all of Asia and the world was stunned by the news of Japan’s victory over Imperial Russia (1904–5). For Vietnamese and other Asians living under European colonial rule, Japan became an inspiration and a model of autonomous modernization. It also briefly served as a haven for Vietnamese anticolonialists such as Prince Cường Để, pretender to the Nguyễn throne, and Phan Bội Châu, a self-proclaimed revolutionary who recruited patriotic Vietnamese youth to “go east” and join the prince in Japan. But this moment of anti-European solidarity was fleeting. In 1909, Tokyo acknowledged French dominion in Indochina and expelled the Vietnamese. This “betrayal” would linger in the minds of many independence-minded Vietnamese, who resolved to seek a different path to revolution.Footnote 4

The crackdown on Phan Bội Châu’s movement coincided with new French efforts to win the support of modernization-minded Vietnamese elites who had remained in Indochina. Instead of calling for revolution and the overthrow of colonial rule, these elites advocated evolution and reform. After the reformer Phan Châu Trinh was freed from prison in Indochina and allowed to move to Paris, other Vietnamese activists joined him in “going west” to Europe. Among those who joined Phan in Paris in the late 1910s was Nguyễn Tất Thành, a young firebrand from Nghệ An province who would soon adopt the alias Nguyễn Ái Quốc (Nguyễn the Patriot). Nguyễn Ái Quốc became part of the “Five Dragons,” a reformist group that also included Phan Châu Trinh, Phan Vӑn Trương, Nguyễn Thế Truyền, and Nguyễn An Ninh. Although all five were critics of colonial rule, Nguyễn Ái Quốc was the only one drawn to more radical forms of socialism. In 1920, as a delegate at the 18th Congress of the French Socialist Party, he voted with the majority in favor of joining the Soviet-led Third International.Footnote 5

Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s radicalization was prompted by his encounter with the works of Vladimir Lenin, not those of Karl Marx. (He once confessed that he tried to read Das Kapital, but ended up using it as a pillow.)Footnote 6 Unlike Marx, Lenin identified imperialism as “the weakest link in international capitalism” and embraced anticolonial struggle through revolutionary means.Footnote 7 By 1920, Nguyễn Ái Quốc had concluded that the reformist cause was hopeless and that the French would neither amend nor abolish colonialism. Revolution was the only route to national liberation. Phan Châu Trinh recognized that he and his young compatriot had the same ultimate aim, even though they diverged over how to pursue it. Phan Châu Trinh urged Nguyễn Ái Quốc to return home and continue the fight for independence.Footnote 8

In the 1940s, Hồ Chí Minh explained his affinity for Marxism–Leninism to a sympathetic American: “First you must understand that to gain independence from a great power like France is a formidable task that cannot be achieved without some outside help, not necessarily in things like arms, but in the nature of advice and contacts. One doesn’t in fact gain independence by throwing bombs and such. That was the mistake the early revolutionaries all too often made. One must gain it through organization, propaganda, training and discipline. One also needs … a set of beliefs, a gospel, a practical analysis, you might even say a bible. Marxism–Leninism gave me that framework.”Footnote 9 These comments reveal key features of Hồ Chí Minh’s personality. He was neither a theoretician nor an adventurer bent on violence. Instead, he was a pragmatist and temporizer who recognized that the surest path to revolutionary success would not be the shortest one, and that the risks of violent struggle sometimes outweighed the prospective gains.

The pragmatic and calculating aspects of Hồ Chí Minh’s personality revealed themselves at key moments throughout his career. He opposed his fellow communists’ plan for a 1940 uprising against France on the grounds that it was premature.Footnote 10 In 1945 and 1946, he temporarily accommodated the demands of two rival anticommunist parties, the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (VNQDĐ) and Đông Minh Hội, until he had negotiated the withdrawal of an occupying Chinese Nationalist Army. He also chose the path of negotiation with the French government in the hope of avoiding war in 1946, even though colonial troops had already attacked DRVN forces in southern Vietnam. That same year, on the eve of the great anticolonial insurrection in Madagascar, two Malagasy delegates asked Hồ Chí Minh what they should do. He urged them to eschew violence and to stay in Paris, saying “There is salvation for all of us in the French Union.”Footnote 11 In 1954, in perhaps his most famously pragmatic act, he made peace with France at Geneva. Despite the DRVN’s stunning victory at Điện Biên Phủ, he accepted the partition of Vietnam into northern and southern zones, as well as a promise of nationwide elections in 1956. For Hồ Chí Minh, a compromise peace agreement was preferable to continued war and to the possibility of direct US military intervention in Indochina.Footnote 12

Hồ Chí Minh’s pragmatic approach to revolution was forged through his involvement in the politics of international communism during the 1920s and 1930s. His career as a Comintern agent and the early history of the Vietnamese Communist Party was deeply shaped by the tensions between two lignes de force: an emphasis on national unity for the sake of anticolonial liberation, and an emphasis on class struggle for the sake of international socialist solidarity. As a result, Hồ Chí Minh’s fortunes and those of the party – which was renamed the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) in 1930 – were deeply tied to events in Asia, Europe, and the Soviet Union, and to the debates and personal rivalries that shaped the constantly shifting Comintern line. For Hồ Chí Minh, the most pressing choices he faced did not involve the primacy of the “national question” over the “social question” (or vice versa), but the difficulty of waging revolution during an era of global economic turmoil, war, and ideological polarization.

From Moscow to Canton

Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s first engagement with international communism coincided with the collapse of leftist revolutionary movements in Germany, Hungary, and Poland during 1919–20. In the aftermath of these failures, the Comintern shifted its attention eastward. Nguyễn Ái Quốc traveled to the Soviet Union for the first time in 1923, where he became a recruit of the Comintern and encountered some of its top leaders such as Dmitry Manuilsky. In 1924, he was dispatched to Guangzhou in southern China to support the Comintern’s recently established alliance with Sun Yat-sen’s Republic of China. For the next three years, Nguyễn Ái Quốc forged close working relationships with senior leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He also recruited many fellow Vietnamese anticolonial activists who had fled French repression inside Indochina.

Southern China in the mid-1920s was a hotbed of revolutionary activism. The best-known Vietnamese militant was Phan Bội Châu, who had relocated to the area after his expulsion from Japan. In 1923, some of Phan Châu Trinh’s followers established the Association of Like Minds (Tâm Tâm Xã), a group dedicated to violent direct action against colonial rule. The following year, Phạm Hồng Thái tried to kill the governor-general of Indochina in a bomb attack; the attempt failed but Phạm Hồng Thái became a revolutionary martyr after he drowned himself to avoid capture.Footnote 13 Revolutionary fervor among Vietnamese rose higher in 1925 when Phan Bội Châu was kidnapped by French operatives in Shanghai, spirited back to Indochina, and sentenced to death. The resulting popular outcry led French officials to commute his sentence to house arrest. The following year, Phan Châu Trinh died in Saigon shortly after returning from France. His funeral procession drew massive crowds and prompted vigils, demonstrations, and strikes across Indochina.

These events demonstrated the growing interest of young Vietnamese people – especially students – in both revolution and cultural transformation. For many Vietnamese youth, like their Chinese counterparts, the problem of foreign domination was part and parcel of a Vietnamese cultural crisis.Footnote 14 To throw off foreign domination, they argued, Vietnam would have to abandon the stultifying traditional practices and values of their conservative elders.Footnote 15 The rising radicalism of Vietnamese youth made many of them receptive to the appeals issued by Nguyễn Ái Quốc, whose recruitment efforts were now moving into high gear.

Thanh Niên: The Revolutionary Youth League

In June 1925, Nguyễn Ái Quốc (now operating under the Chinese alias Lý Thụy) opened a school in Guangzhou and began training a group of fifty aspiring activists. The most promising members of this group would later become known as the “Communist Youth group” (Thanh niên cộng sản đoàn). Five members of this hand-picked elite would subsequently go to Moscow to study at the University of the Toilers of the East, later known as the Stalin School.Footnote 16

In building the membership and reach of the Revolutionary Youth League (Thanh Niên Cách Mạng Đồng Chí Hội), Nguyễn Ái Quốc deployed the full range of his organizational and pedagogical talents. He taught most of the courses and was practically the sole author of the journal Thanh Niên. He wrote also for other radical publications (Báo Công Nông, Lính Cách mạng, and Vietnam Tiên Phong). He expressed himself with simplicity and clarity – qualities that young people (especially those with little or no formal education) found appealing.

Nguyễn Ái Quốc/Lý Thụy presented his core ideas in a sixty-page booklet entitled The Revolutionary Path (Đướng Cách mệnh). He emphasized Lenin’s basic principle that there is no revolutionary movement without revolutionary theory. He also argued that the latter serves no purpose if there is no party to carry it out. He critiqued reformism, anarchism, Gandhism, and the three principles of Sun Yat-sen to point out their limitations. Unexpectedly, he affirmed the importance of Confucius as a source of wisdom and inspiration: “As far as we are concerned, we Annamites, let us perfect ourselves intellectually through the reading of Confucius, and revolutionarily through the works of Lenin.”Footnote 17

During his time in Canton, Nguyễn Ái Quốc aimed to educate his readers about concepts such as revolution, the proletariat, workers’ unions, cooperatives, and so on. But his goals went far beyond teaching vocabulary. He was also working to establish a Vietnamese communist movement, if not a party. In addition to building a network of activists and disseminating ideas, he sought to initiate his young compatriots into a political culture that blended East Asian ethics with European ideas about modernity – a process that Huỳnh Kim Khánh called “grafting.” In the late 1920s, amid political turmoil and increased competition among radical groups, Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s work would lead to the emergence of a new communist party.Footnote 18

The Founding of the Indochinese Communist Party

In 1927, Chinese nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek severed his alliance with Moscow and launched a viscious crackdown on the Chinese Communist Party. Several dozen Thanh Niên members and other Vietnamese who had studied at the Whampoa Academy escaped and joined the communists’ Red Army units at Hailufeng, Baise, and other base areas. Nguyễn Ái Quốc drew several important lessons from the failure of the communists’ united-front strategy and the subsequent struggle of the Chinese communist movement for survival. Chief among these was the idea that the Communist Party must play a hegemonic role in its dealings with allied groups and organizations.

In addition to advocating for an autonomous communist party in Indochina, Nguyễn Ái Quốc was now determined to connect the “national question” to the “social question” in ways that would ease the tension between the movement’s patriotic and communist goals. The communists needed a bow with two strings: “I am committed to making sure that in the future we will make the principles of Lenin and Sun Yatsen the guiding light of the Vietnamese revolution.”Footnote 19 Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s experiences in China also convinced him of the paramount importance of mobilizing the peasantry and of its revolutionary potential – especially in countries in which industrial workers remained a tiny minority. On this matter, Nguyễn Ái Quốc agreed with Jacques Doriot, the French communist envoy, whom the Comintern sent to Canton in 1927.Footnote 20

Although Nguyễn Ái Quốc was circumspect about the ideological disputes that raged within the Bolshevik Party and in the Comintern during these years, it seems likely that he believed that these debates had weakened the Chinese Communist Party. Witnessing the “tragedy of the Chinese Revolution” during the 1920s made him skeptical about the value of theoretical polemics.Footnote 21 His experiences in China thus strengthened his fundamental pragmatism.

In the aftermath of the nationalist crackdown in China, Nguyễn Ái Quốc continued to travel and work for the Comintern. He visited Moscow, Brussels, and Berlin, then returned to the “Nanyang” region (Southeast Asia) with missions to Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Laos. The Malayan communist leader Chin Peng remembered Nguyễn Ái Quốc playing a central role in the 1930 founding of the Malayan Communist Party as a Comintern representative.Footnote 22 Although he faithfully served as a Comintern missionary, he yearned to return home to participate in the revolutionary movement in Indochina.

As Nguyễn Ái Quốc continued his work overseas, the other members of Thanh Niên dispersed, with many of them slipping back into Vietnam. As the workers’ and farmers’ unions attracted new members, some activists wanted to reorganize the league into a formal communist party. In June 1927, Thanh Niên fractured into three groups known respectively as the Indochinese Communist Party, the Indochinese Communist League, and the Communist Party of Annam. All three groups were led mostly by well-to-do men with backgrounds as landlords, rich peasants, colonial functionaries, or merchants. Many had studied at Franco-Annamite schools.

During 1927–9, Tonkin and northern Annam were shaken by waves of strikes and protests by workers and farmers. Many of the ex-Thanh Niên activists advocated for proletarianization (vô sản hóa) of the movement, and for focusing on the world of industrial laborers. In doing do, they were following the political line laid down in 1928 at the Comintern’s 6th Congress, which called for a “class against class” approach. They may also have been compensating for their own social and cultural backgrounds.

In late 1929, Nguyễn Ái Quốc was called to Hong Kong from Thailand to fuse the feuding factions into a single communist party. Citing his status as representative of the Comintern, he executed this mission during the “Unity Conference” held in January and February 1930. Although the new party was christened the Vietnamese Communist Party, its founding program emphasized struggle against feudalism and capitalism as much as national liberation.Footnote 23

Although Hồ Chí Minh succeeded in unifying the squabbling factions, his tenure as head of the new party was short-lived. In October 1930, the organization was renamed the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) and the Comintern assigned Trần Phú (a Thanh Niên recruit who had recently returned from training in Moscow) to write a new political platform that was more in keeping with the Comintern’s current emphasis on class struggle. The Comintern subsequently admitted the ICP as a party separate from the French Communist Party.

Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s influence within the ICP declined sharply after 1930. He complained that his comrades considered him no more than a “mailbox” and they no longer allowed him to participate in party decision-making. He was subsequently scapegoated for the failure of the Xô Viết Nghệ Tĩnh, a massive uprising in Central Vietnam during 1930–1 that was crushed by French security forces.Footnote 24

By mid-1931, the wave of revolutionary activism within Indochina had ebbed away, and Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s fortunes had taken a turn for the worse. He would spend the next seven years in the political wilderness. Briefly jailed by British authorities in Hong Kong, Nguyễn Ái Quốc regained his freedom and made his way once again to Moscow. He remained there for four years, during Stalin’s purges. He survived, though how he managed to do so remains unclear.Footnote 25

Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s fall from grace was confirmed at the ICP’s March 1935 Congress, held in Macau. Hà Huy Tập, the new general secretary, dismissed him as “a petit bourgeois nationalist” and described how the party was eradicating the “remnants” of his misguided ideas. “This pitiless struggle against the old opportunist theories of Nguyễn Ái Quốc and Thanh Niên is indispensable,” Tập wrote. “We propose that comrade Line [Nguyễn Ái Quốc] himself write a brochure to criticize himself and his past failings.”Footnote 26 That summer, when the Comintern held its 7th International Congress in Moscow, Nguyễn Ái Quốc was not a member of the ICP delegation, serving instead in the minor role of translator for the group.

Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s Political Resurrection

Although 1935 was arguably the nadir of Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s revolutionary career, it also marked a turning point in the history of international communism – one that would eventually pave the way for Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s political comeback. At the 7th Congress, the Comintern abandoned its “class against class” line in favor of seeking a broad united front against fascism. This effectively overturned the policies endorsed by the ICP leadership earlier in the year at Macau. After the French Communist Party dutifully adopted the new Front populaire line, the ICP followed suit, calling for a “Indochinese democratic front” to oppose fascism and Japanese imperial expansion. By 1937, the ICP leadership was specifically warning its members to avoid fomenting class tensions. “It is not yet time to prepare anti-imperialist and agrarian revolution,” the Central Committee admonished its members. “[Instead,] it is time to actualise united popular front to get helpful reforms for all. Hence, we have to tell daily workers to restrain hostility against well-to-do as poor farmers …”Footnote 27 In another document, the leadership advised its cadres to “skillfully lead” the landlords and rich farmers to participate in anti-tax protests, and to defer any attempts to destroy their social power.Footnote 28

These policies marked a new willingness on the part of the Comintern to wrestle with the “national question.” Since the early 1930s, communist parties in colonized countries had often been obliged to suppress their nationalist feelings. But Comintern leaders remained aware of the tensions between the national and social questions. Indeed, this was far from the first time such concerns had been raised. As far back as 1930, Trotsky himself had warned his “Indochinese comrades” that rejecting the “national factor” out of hand was likely to backfire.Footnote 29

In Moscow, Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s escape from Stalinist terror hinged on the protection provided by the leaders of the Comintern Far Eastern branch, who believed he could still be useful to the movement.Footnote 30 In 1938, he departed Moscow for China, leaving on the same day that Stalin ended the reign of terror of Nikolaï Iegov, the head of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Narodny komissariat vnutrennih del – NKVD). Nguyễn Ái Quốc spent most of the next three years in the recently established Chinese communist base areas in Guanxi, where he absorbed the innovative mass mobilization tactics that Mao Zedong was in the process of devising.Footnote 31 Throughout this time, he continued to follow events in Indochina closely. His fidelity to the Comintern was on display in his denunciations of what he described as the “treason” of the Vietnamese Trotskyists, who had briefly cooperated with ICP members during the popular-front period.Footnote 32

Nguyễn Ái Quốc also paid close attention to the changing geostrategic situation in Asia and Europe. In 1937, Imperial Japan launched an all-out invasion of China. Following the fall of France in 1940, Japanese leaders forced the pro-Vichy colonial regime to permit Tokyo’s forces to occupy northern Indochina. By 1941, Japanese troops were using France’s empire as a base and springboard for their planned expansion into the rest of Southeast Asia. Amid the upheaval, Nguyễn Ái Quốc perceived new openings. He summed these up in a poem: “Now France is occupied/ the Japanese pirates just arrived/ Chinese, Americans, Dutch, English arrive together/ War and its troubles are raging everywhere/ This presents a good occasion for us.”Footnote 33 Having survived police surveillance, criticism, demotion, detention, and Stalinist terror, Nguyễn Ái Quốc now prepared to return to his native land for the first time in three decades. The pragmatic revolutionary was determined that the emerging opportunities he saw would not be wasted.

Renewing the Drive for Independence

Nguyễn Ái Quốc was still very much acting as an agent of the Comintern when he convened the Eighth Conference of the ICP Central Committee at Pác Bó near the Vietnam–China border in May 1941. The six men present agreed with Nguyễn Ái Quốc that the Indochinese revolution, though a struggle for national liberation, remained an integral part of the worldwide socialist struggle, its fate linked to that of the Soviet and Chinese revolutions. Those present also agreed that, to attain their goals, they needed to throw open their ranks to as many Indochinese as possible. This meant they would have to put their plans for a radical agrarian revolution on hold. The liberation they now envisioned would be achieved via armed struggle led by the ICP and would continue until all the peoples of Indochina (including Cambodians and Lao) were free of the French colonial yoke.

During the conference, Nguyễn Ái Quốc (still not yet known as Hồ Chí Minh) proposed the creation of a united national front called “The League for the Independence of Vietnam,”or Việt Nam Độc lập Đồng minh hội (soon to be abbreviated as “Việt Minh”). Having learned the lesson of the “Chinese tragedy” of the 1920s, all members of Việt Minh’s general directorate (tổng bộ) were communists. On June 6, Nguyễn Ái Quốc issued an appeal to the people of the nation, announcing that French colonial domination was nearing its end and calling for everyone to unite and bring about the liberation of the country.

With these goals in mind, Nguyễn Ái Quốc published “The Ten Policies of the Việt Minh” that summed up the objectives of the united front. He also wrote a “History of our country” (Lịch sử nước ta) in verse:

Contrary to what some authors later alleged, these declarations were not heretical by the current standards of the Comintern. Nguyễn Ái Quốc was very much in step with the resolutions of the 7th Congress and the directives issued by its president to the delegates from colonized countries. In 1943, Comintern chief Georgy Dimitrov urged them “to explain to the laboring masses in an historically objective way their nation’s past, to link their current struggles with the traditions of their people.”Footnote 35

On August 1, 1941, Nguyễn Ái Quốc published the first of 150 issues of a journal he would write and edit almost singlehandedly. Entitled Independent Vietnam (Việt Nam Độc lập), it became a key means for him to popularize his ideas, demands, and advice. Although his aims remained pedagogical, Nguyễn Ái Quốc eschewed theory and dogma, seeking instead to be understood by an illiterate mass.

Over the next four years, Nguyễn Ái Quốc carefully prepared the ICP for the day when he and his comrades could take power. In part, this involved efforts to build rudimentary guerrilla units and bases in the mountains of northern Tonkin. But it also involved diplomatic outreach efforts, the most important of which involved the United States. It was during his clandestine travel to meet with US commanders in southern China that Nguyễn Ái Quốc first adopted the alias Hồ Chí Minh, meaning “Hồ the enlightened” – a moniker that seemed calculated to appeal much more to nationalist unity than to socialist revolution.Footnote 36

In August 1945, the news of Japan’s surrender prompted Hồ Chí Minh to convene a national conference at Tân Trào, just over 80 miles (130 kilometers) from Hanoi. There, a gathering of ICP members and sympathizers quickly approved the creation of a provisional government, with Hồ Chí Minh at its head. At this critical moment, the ICP’s ability to control events at the local level across Indochina was severely limited. But Hồ Chí Minh still recognized the importance of seizing the opportunity to assert independence. He made his way to Hanoi, where he proclaimed the birth of an independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam on September 2, 1945. In his speech – the most famous and most celebrated he would ever deliver – he made no mention of class struggle or social revolution. Instead, he called on all Vietnamese patriots to come together under the banner of đại đoàn kết (great unity). Not coincidentally, this moment also marked the first emergence of what would eventually become a full-fledged cult of personality around Hồ.

Hồ Chí Minh’s emphasis on national unity led to what would become one of his most controversial decisions: his November 1945 announcement of the dissolution of the ICP. Although the announcement was a ruse – the party merely shifted its operations underground – the move was opposed by some of his comrades. Indeed, in a different time and context, such a step would have led to Hồ Chí Minh’s prompt expulsion from the international communist movement (as experienced by American communist chief Earl Browder following his decision to dissolve the US Communist Party). But in the context of Indochina in 1945, Hồ’s decision made sense. Over the objections of some advisors, he freed the Vietnamese Catholic leader Ngô Đình Diệm from detention; he also sought support from prominent noncommunists such as Bishop Lê Hữu Từ and ex-emperor Bảo Đại. In early 1946, he consented to reserve a total of seventy seats in the new DRVN National Assembly for the nationalist VNQDĐ and Đông Minh Hội parties. He also signed a modus vivendi with French leaders and traveled to the metropole in mid-1946 to take part in negotiations at Fontainebleau, all in the hopes of avoiding war with the colonial state.

Yet these pragmatic – and ultimately unsuccessful – efforts to avoid war did not mean that Hồ Chí Minh had abandoned his Leninist convictions. Even as he preached unity and urged noncommunist groups and leaders to join the DRVN government, he made sure that key posts and ministries remained in the hands of senior Communist Party figures such as Võ Nguyên Giáp. Moreover, his outreach to his nationalist rivals was based on tactical expediency, not on a genuine commitment to inclusion. By late 1946, the ICP had abandoned its short-lived alliance with the nationalist parties and resumed cracking down on those deemed “traitors” to the revolution.

It was not long before Hồ Chí Minh’s bona fides as a genuine communist were reaffirmed. In 1949, two Vietnamese party members – one of whom was the younger brother of Trần Phú, who had replaced Hồ Chí Minh as ICP leader in 1931 – accused Hồ Chí Minh of “betraying” the movement. In their view, the public dissolution of the ICP in 1946 was proof that Hồ Chí Minh had embraced an “opportunist” and “nationalist” position.Footnote 37 This was substantially the same accusation leveled at Hồ Chí Minh by Hà Huy Tập in 1934. But in 1949, Hồ Chí Minh had the strong backing of the Chinese communists; his standing was affirmed by the endorsement of the French Communist Party (PCF), which sent representatives to meet Hồ Chí Minh at his mountain headquarters.Footnote 38 As historian Alain Ruscio has suggested, the PCF had become more tolerant of nationalism in Vietnam due to its own participation in the wartime resistance against the German occupation of France.Footnote 39 Not surprisingly, the accusations against Hồ quickly fizzled out, and the accusers ironically found themselves under suspicion of advocating Trotskyism.

Although Nguyễn Ái Quốc had been sidelined by the Moscow-trained cohort of Vietnamese “Bolsheviks” during the 1930s, a different fate awaited Hồ Chí Minh in the 1940s. As a committed Leninist who had always viewed national liberation as the route to socialist revolution, Hồ Chí Minh was perfectly in tune with the strategies that the Comintern and Moscow adopted in response to the shifting international situation. For Hồ Chí Minh, Leninism remained both “a compass for us Vietnamese revolutionaries and people” and “the radiant sun illuminating our path to final victory, to socialism and communism.”Footnote 40

Beyond National Liberation

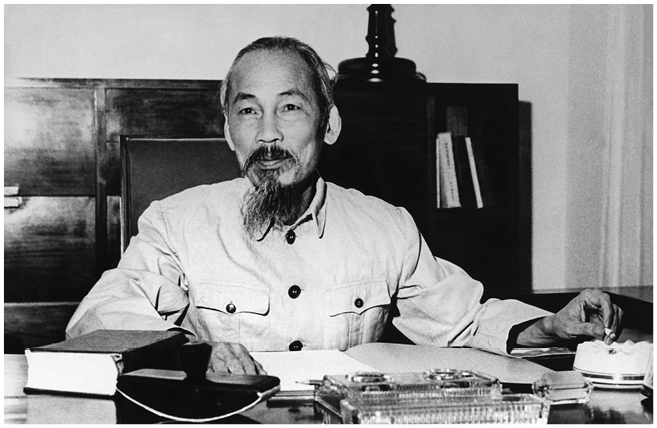

By the time of the DRVN’s spectacular battlefield victory at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, Hồ’s position as the public face and irreproachable hero of the Vietnamese Revolution seemed unassailable (Figure 3.1). Moreover, the Communist Party he had founded, now reborn as the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP), now wielded unquestioned control over the DRVN state. Nevertheless, Hồ Chí Minh would not be immune from the debates and rifts that would shatter the unity of the international communist bloc during the 1950s and 1960s. He would also subsequently find himself marginalized within his own party, as other Vietnamese communist leaders moved to assert control over DRVN policy and strategy. Thus, even as Hồ Chí Minh’s cult of personality and international stature expanded, his personal power – even the power to shape his own image – went into eclipse.

Figure 3.1 Hồ Chí Minh, the president of the Democratic Republic of North Vietnam, in his office at the Presidential Palace in Hanoi (May 27, 1955).

The DRVN’s land reform program, carried out in 1953–6 in north-central and northern Vietnam, was a watershed in both the history of Vietnamese communism and in the evolution of Hồ Chí Minh’s public image. Urged on Hồ Chí Minh by Stalin and implemented according to the blueprints devised by Mao, this program aimed to consolidate the Communist Party’s revolutionary authority by destroying the power of landlords and rich peasants in North Vietnamese rural communities. Even those who had loyally supported the revolution on patriotic grounds now faced expropriation, denunciation, imprisonment, or death. Although the power of these landed elites was shattered, many middle and even poor peasants were also targeted. Party leaders eventually acknowledged these “errors” and Hồ Chí Minh issued a public apology.Footnote 41

In the wake of these admissions, some party insiders insisted that Hồ Chí Minh had been skeptical of the program from the outset, especially the targeting of patriotic landlords and revolutionary supporters.Footnote 42 But recent research has cast doubt on these claims, suggesting that the program was the logical extension of the Maoist mass mobilization strategies that Hồ knew well and which the Vietnamese communists had begun to implement during the 1940s.Footnote 43 Hồ Chí Minh’s alleged reservations aside, it is clear that the program damaged his standing and authority within the Communist Party. Although the party continued to burnish his public image, his role was increasingly that of a figurehead. By the early 1960s, party policy and strategy was under the firm control of a new troika of leaders: Lê Duẩn, Lê Đức Thọ, and General Nguyễn Chí Thanh.Footnote 44

Hồ Chí Minh’s damaged standing can be seen in a 1963 internal report by Chinese communist leader Liu Shaoqi, who singled Hồ Chí Minh out for criticism:

Ho Chi Minh has always been a rightist. When we implemented land reform, he resisted. He did not want to become the chairman of the Vietnamese Workers Party and preferred to stay outside the party and become a nonpartisan leader. Later, when the news went to Moscow, Stalin gave him a harsh lecture. It was only then that he decided to implement land reform. After the war with French, he could not decide whether to build a capitalist or a socialist republic. It was we who decided for him.Footnote 45

Liu’s denunciation of Hồ Chí Minh was undoubtedly shaped by the emerging Sino-Soviet split. It also presaged the bitter estrangement between the Chinese and Vietnamese communist parties that would emerge after 1968 and eventually culminate in Beijing’s 1979 invasion of northern Vietnam. Still, it is striking how Liu’s critique echoed the accusations leveled against Hồ Chí Minh by Hà Huy Tập in 1935. Hồ Chí Minh had survived the internecine ideological combat that wracked the international communist movement in the twentieth century, but he had not emerged unscathed. Although his status as a symbol of Vietnamese unity had been firmly cemented, he was in some respects more isolated and more remote from the Vietnamese masses that he had long claimed to serve.

Going Down in History

The complex history of Hồ Chí Minh’s relationship with the Vietnamese Communist Party raises broader questions about the connections between individuals and history, as well as between individuals and communities. Hồ Chí Minh’s central importance in modern Vietnamese history is indisputable. Yet his life and career cannot be plausibly separated from the international communist movement that he joined and served for decades, or from the Communist Party that lionized him.

The extent to which Hồ Chí Minh’s fate was bound up with that of the international communist movement is evident in the impact of the Sino-Soviet split on him and on his comrades.Footnote 46 According to the testimony of Hoàng Tùng and other party insiders, Hồ Chí Minh was dismayed not only by the fractures between the DRVN’s two most important allies after 1960, but also by the tensions and divisions that the split produced within the Vietnamese Communist movement.Footnote 47 Hồ Chí Minh himself famously refused to take sides – even going so far as to offer to mediate between Moscow and Beijing – perhaps because he had so many personal ties to colleagues in both countries. Of course, those ties had been forged during his decades of dedicated service as a Comintern agent. As a true believer in Leninism, he had apparently internalized Lenin’s understanding of politics and his notion of democratic centralism as a foundational principle of party governance.

Hồ Chí Minh’s subordination to the communist movement and to the party extended to virtually all aspects of his life. Although the party insists today that Hồ was never married, research has revealed that he wed a Chinese midwife named Tang Tuyết Minh in Canton during the 1920s. Separated from her husband during the 1927 nationalist crackdown, Minh later wrote to him when he was president of Vietnam. But neither Chinese nor Vietnamese authorities had any interest in allowing her to re-establish contact.Footnote 48 During the resistance years, Hồ Chí Minh was romantically linked to a Tày woman named Đỗ Thị Lạc. She hoped to marry him, but the Politburo forbid it, and her premature death gave rise to rumors of murder.Footnote 49

Nor did Hồ Chí Minh’s service to the party end with his death in 1969. In his testament (di chúc), he asked for his body to be cremated and the ashes scattered at the four cardinal points of the country. But even in death, the cult of Hồ Chí Minh’s personality was too valuable to be dismantled. The text of his testament was suppressed and only a truncated version was published. Party leaders then decreed that his body should be embalmed and preserved in a Hanoi mausoleum for viewing by pilgrims and tourists. It remains there to this day.Footnote 50

As much as any other fact about the life and career of Hồ Chí Minh, his postmortem treatment sheds harsh light on the true nature of his role in building and maintaining the power of the party that he founded. One is hard pressed to imagine a more poignant or convincing demonstration of the concept of the “social virtue of a corpse.”Footnote 51 The edifice of Hồ Chí Minh’s mythology remains as imposing as ever today, even as the man behind it, like the body under glass at the mausoleum in Hanoi, remains just out of reach.