Chapter 1 Sung government and politics

Introduction

The Sung dynasty (960–1279) marked a key transition in the long course of Chinese history. The first hundred years of Sung rule witnessed fundamental economic and social changes that transformed the lives of all elements in society, from emperor to peasant. Yet the same period that brought these sweeping changes also marked a high point in Chinese intellectual and cultural life. Sung scholarship, art, and technology are among the glories of Chinese civilization and have prompted some scholars to compare the eleventh century in China to the Renaissance in Europe. The comparison, however tenuous it becomes under scrutiny, well underscores this general spirit of innovation and creativity that is a hallmark of Sung civilization. Understanding this apparent paradox – how rapid social change coexisted with the stability necessary for lasting cultural achievement – is key to understanding the Sung. Much Sung discourse contains an acute tension that arises from a distinctive and willful joining of opposites: old and new, practical and theoretical, strength and delicacy. The vigorous lines and refined fragility of Sung white porcelain find a parallel in the reflections of the great eleventh-century political thinkers who wrote and struggled to transform a world they feared could shatter at any moment.

A Japanese journalist turned academic, Naitō Torajirō (1866–1934), formulated a theoretical model that posits and attempts to explain this transitional character of the Sung period. Although modern scholars no longer accept key elements of Naitō’s thesis, the “Naitō hypothesis” has framed academic research on Sung history, especially in Japan and the United States, for much of the past century. According to Naitō, the Sung marked the transition in China from a “medieval” to a “modern” society, modern in the sense that Naitō believed that major elements of the Chinese society he knew – the late Ch’ing (1644–1912) – had originated in the Sung.

According to Naitō and his successors, the Sung unification of China after the political fragmentation of the late T’ang (618–907) and Five Dynasties (907–60) unleashed pent-up economic forces that rapidly transformed Chinese society in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. Agricultural advances in both the growing and commercialization of rice and tea generated a drastic increase in trade and an expansion of copper- and silver-based currency. These changes brought new wealth to the countryside and an increased population, especially in the south. This produced both a rise in the independent status of commoners, who had been virtual “slaves” under earlier dynasties, and a new class of official and bureaucratic elite. This latter group, ancestor of the later “gentry” of Ming and Ch’ing times, formed the base of a new ruling elite that displaced both the older hereditary “aristocracy” of Six Dynasties (222–589) and T’ang and the nonaristocratic military families who had ruled during the ninth and tenth centuries.

Naitō also believed these changes brought an increase in status and power to the emperor and so resulted in the “monarchical dictatorship” characteristic of late imperial – that is, “modern” – China. In “medieval” times, the emperor’s social status was on par with, or even sometimes inferior to, that of the “aristocracy” with whom he shared power and through whom he ruled. Although certainly more than a figurehead, the emperor ruled in consort with them and could not act against their interests. But the rise of militarism and the decline of aristocracy in the Late T’ang and Five Dynasties removed this relationship between the emperor and his top officials. The early Sung emperors, themselves soldiers, seized this opportunity to redefine the role and enhance the power of the sovereign. Distrustful of their own military peers, they revised the old T’ang examination system and used it to recruit shih ta-fu (literally “servicemen and grand masters”), essentially a new civil service, from among the emergent commoners and nouveau riche. The emperor’s social status was now far above that of his officials. He assumed “dictatorial” powers because only the sovereign, through the examination system, now controlled access to office. This new centralized bureaucracy of Sung was more beholden to the throne and so supported imperial power in a different manner and on a greater scale than had its medieval forebears.1

The great virtue of Naitō’s synthesis was to focus attention on the rise of the centralized bureaucracy in the early Sung, on the importance of the civil service examinations in the process of its formation, and on the vast social and cultural divide that separated the T’ang ruling class from that of Sung. Modern research on Sung government and politics has lavished attention on Sung officialdom, its composition, its education, its ethos, and on the institutional structures that supported it. However, Naitō’s journalistic exposure to the corrupt monarchy of late nineteenth-century China certainly influenced his concept of “monarchical dictatorship,” and many scholars of Sung history now question how well the notion of imperial autocracy describes the Sung rulers. Recent research on the interaction between the Sung monarchs and their officials suggests a more nuanced and balanced relationship than the concept of either dictatorship or autocracy entails. The Sung monarchs were indeed different from their T’ang predecessors, but they were just as different again from their clearly more authoritarian successors in Ming and Ch’ing.2

The lasting legacy of Sung rule was the creation of the “modern” notion that China is one place, one country, and the formation of the institutional mechan-isms necessary to sustain that notion. During the tenth century, the period of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (902–79), centrifugal tendencies that had accumulated since the An Lu-shan (703–57) rebellion in 755 almost split China into multinational states, similar to Europe after the Roman Empire (27 bc–ad 395). There were ample historical and theoretical models for a Chinese multinationalism – the Warring States (476–221 bc), the Three Kingdoms (220–80), the Six Dynasties. Furthermore, the existence of non-Chinese “alien and border states” such as the Khitan Liao dynasty (907–1125) and their control over Chinese-speaking populations in the north and west initially created another dynamic toward acceptance of multinational states.

The advent of Sung put a halt to the realization of such “splittist” tendencies forever. China remains to this day a country of stark regional divisions, but the modern, and still delicate, balance between center and province is a legacy of Sung. Abandoning exclusive reliance on either the hereditary houses or the military, the early Sung monarchs created a polity that drew cultural regions and social groups together. Sung officials often write with a firm sense that they share in the health of the body politic. In truth, the Sung mon-archs fostered shih ta-fu government as a means to strengthen their own control over the country’s burgeoning wealth. Yet despite the questionable integrity of the imperial motive, the centralized bureaucracy they created was a powerful force that spread a common political education, culture, and ethic across the disparate regions of China. Never again would regionalism gain enough traction to outpace centralism as a major organizational force in the Chinese mentality – the “new” empire was here to stay.3

And that new empire was among the most entrepreneurial in Chinese history. When the shih ta-fu emerged as the ruling class, they used their power – with the support of the Sung emperors – to accumulate large landed estates and to seize control of commercial activity. The estates transformed medieval patterns of land tenure and underlay the economic foundations of Sung officialdom.4 The rapid expansion of the population into south China, technological innovations in agriculture, and the growth of a nationwide trade network made these lands more productive and valuable.5 At the same time, the coastal cities of the east and southeast emerged for the first time in Chinese history as major centers of shipbuilding and international trade.6 The rapid urbanization and growth of commercial enterprises provided many opportun-ities for the Sung state to exercise its entrepreneurial ingenuity.7 Early in the dynasty, over 2,000 tax collection centers were established in rural market towns and fairs to collect a sales tax of 3 percent and a transport tax of 2 percent on the retail price of merchandise. Revenues from this source increased fivefold by the middle of the eleventh century.8 The state itself was also the largest landlord. By 1077, half the total commercial tax revenues collected in the capital city of K’ai-feng came from rental income on state-owned property.9 The government and its agents seldom missed an economic opportunity. For example, commercial activity in K’ai-feng grew so rapidly in the eleventh century that shops and retail outlets expanded and encroached onto public streets. After years of trying to stem the trend, the state finally acquiesced and levied in 1086 a new “street encroachment tax” (ch’in-chieh ch’ien) on offenders not only in the capital but over the entire country.10

A few economic numbers may help to visualize the rapid growth of the centralized Sung state and render a feel for the efficiency of its operation. Between the last decade of the tenth century and the first decade of the eleventh, annual revenues of the Sung government doubled, and its yearly budgets moved from deficit to surplus financing. Top advisers to Emperor Chen-tsung (r. 997–1022) acted between 1006 and 1017 to create a centralized finance system that defined and protected the emperor’s personal share of this wealth, both intertwining and demarcating the line between state and imperial moneys. The emperor’s personal income, based on decennial averages, nearly doubled between the second and the third decade of the eleventh century. These increases reflect not only overall growth in the economy but also the efficiency of Sung government – and the Sung monarch – in extracting a significant portion of national wealth. As early as the 980s, over half of the emperor’s income derived from government monopoly sales of import goods, tea, and salt.11 This entrepreneurial spirit – the close intertwining of government, business, and emperor that manifested itself a hundred years later in the fiscal aggrandizement of Emperor Shen-tsung (r. 1067–85) and Wang An-shih (1021–86) – was present in Sung government from the start.

Contrary to what might be expected, the numbers involved were much larger than for later periods in Chinese history. A comparison of government revenue for two years, 1064 and 1578, reveals that, although revenue from agricultural sources was virtually identical, revenue from nonagricultural sectors under the Sung was an astounding nine times greater than under the Ming (1368–1644).12 It would also appear that Sung government succeeded in appropriating a comparatively large portion of national income. Sung writers, especially in the Southern Sung (1127–1279), often mention the oppressive tax burden on the population and claim that never in history had a government extracted more in taxes from its people.13 Modern estimates confirm these claims. During the Ming–Ch’ing period, Chinese government collected between 6 and 8 percent of national income as taxes. Nineteenth-century European states collected from 4 to 6 percent. Estimates for the Sung rely on more tenuous data, but nevertheless range from a low of 13 percent to an astounding 24 percent.14 By the middle of the twelfth century, overpopulation, incessant taxation, and continual militarization for border defense put severe strains on the former economic prosperity of Northern Sung (960–1127).15 But, that any state could extract such a burden from its population without generating substantial resistance demonstrates both its organizational efficiency and a general consensus on its goals and objectives between governors and governed.

A bibliographic prelude

It may be useful to preface the ensuing description of Sung government with a few cautionary remarks on surviving sources and how they affect research on Sung institutional history. This chapter relies as much as possible on primary sources. Yet there are problems. The Sung was among the most document-driven of all Chinese states and compiled its own history from the plethora of bureaucratic records generated during the course of routine administration. But few of these records survive in their primary form. The present Sung hui-yao chi-kao (A draft compendium of Sung documents), the largest collection of such material, was compiled only in the nineteenth century by copying texts from the Yung-lo ta-tien (Yung-lo encyclopedia), itself a large compendium completed under the Ming dynasty in 1408.16 Documents in the Compendium have thus been extensively edited, copied, abridged, and recopied. The Compendium preserves a large number of primary texts, but these often survive only in truncated and battered condition. They should be used wherever possible in tandem with related texts from other sources.

Two surviving works also derive in a rather direct way from primary records compiled by official Sung historians, and, together with the Compendium of Sung documents, constitute the core sources for research on Sung political and institutional history. The Hsü tzu-chih t’ung-chien ch’ang-pien (Long draft continuation of the comprehensive mirror that aids administration) by Li T’ao (1115–84), completed in 1183, was originally a draft chronological history of the Northern Sung from 960 through 1127.17 The Chien-yen i-lai hsi-nien yao-lu (Chronological record of important events since 1127) by Li Hsin-ch’uan (1167–1244), completed about 1208, was a chronological history of the early Southern Sung from 1127 through 1163.18 Both works are masterpieces in the great tradition of Chinese history writing. Li T’ao and Li Hsin-ch’uan both served as official court historians with access to official resources and archives. Yet both designed and wrote their histories as correctives to the official record, during periods of service outside the court. In other words, both historians were keenly aware that the ebb and flow of political events had already influenced and distorted the dynasty’s primary historical record.

Furthermore, neither of these works, so central to the study of Sung history, has survived intact to modern times. As in the case of the Compendium of Sung documents, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century scholars culled quotations from the Yung-lo encyclopedia to re-create the present texts of the Long draft and the Chronological record. Somewhere in this process, probably in the late twelfth or thirteenth century, major portions of Li T’ao’s Long draft went missing and the Chronological record was disfigured with a spurious commentary that sometimes distorts its original intentions. The pattern of the lacunae in the Long draft is highly suspicious. Missing are the years 1067–70, 1093–7, and 1100–27, in other words, those years that saw the rise of Wang An-shih and his implementation of the New Policies (Hsin-fa), plus most of those years, including the entire reign of Emperor Hui-tsung (r. 1100–26), when Wang’s successors were in power. These lacunae, plus the tone of the added commentary in the Chronological record, suggest that adherents of Tao-hsüeh (Learning of the Way) tampered with the texts of both works. Tao-hsüeh, a late Sung intellectual movement, opposed Wang An-shih and formulated a view of Sung history that blamed Wang, his policies, and his successors for the fall of Northern Sung in 1127 and for many ills in Southern Sung as well.19

The surviving historical record of once primary Sung documents thus ranges from adequate to ample for the beginning and middle portions of both the Northern and Southern Sung, but from meager to nonexistent for the conclusions of both periods. The problem is particularly acute for the period from 1224 through the end of the dynasty, since the official historians were still processing raw data from this period when Lin-an (Hang-chou) fell in 1276. This uneven distribution in the documentary base has shaped and colored research on the Sung. It encourages synchronic studies on periods for which sources are rich, and frustrates such studies for the other periods. At the same time, this shifting depth in the database hampers the design of diachronic studies of institutions across the broad spectrum of the entire dynasty. One needs therefore to support official documents with as many private sources as possible and always pay special heed to matters of provenance and textual integrity.

The teleological arrangement of many Southern Sung collections of primary sources is another problem related to the rise of Tao-hsüeh in the late Sung. Modern descriptions of Sung government often rely heavily on material from Southern Sung encyclopedias. Although these works contain valuable primary sources, their selection, editing, and arrangement often follow a Tao-hsüeh agenda and push a distinctive vision of Northern Sung history.20 They should be used with caution and always in conjunction with other sources of primary documentation. A major exception is the Yü-hai (Jade sea), compiled by Wang Ying-lin (1223–96), the last of the great Sung scholars, a work largely free of overt Tao-hsüeh influence.21

Another problem is institutional change. Traditional sources, such as the monograph chapters on government institutions in the official Sung-shih (Sung history) of 1345, begin their accounts with a general description of an individual agency or position, then follow with a chronological record of mandated changes.22 But these descriptions are often bureaucratic reworkings of original edicts and orders that prescribed how things should be. The descriptions are generalized and abstract, and rarely describe actual practice. The ensuing changes may or may not have taken effect; there is seldom indication when or if a given modification ended or was itself changed yet again. The Western pioneer of research on medieval Chinese institutional history, Robert des Rotours, worked over twenty years meticulously to translate the chapters on government institutions from the Hsin T’ang-shu (New T’ang history), only at the end of his career to realize and acknowledge the highly theoretical and prescriptive nature of his text.23 An account of Sung government based solely on such official sources and their later derivatives would be valid for no actual time and place, because these sources describe an ideal, not a living thing.

A related problem is the constantly evolving, changing, and ad hoc nature of Sung government. Institutional historians of other periods in Chinese history may look upon the Sung as a hopeless muddle of overlapping agencies, jurisdictions, and titles; and they often portray Sung government from the vantage points of earlier or later dynasties. I have in the ensuing pages tried to present an image of Sung political institutions that is both general enough to offer a coherent overview, yet detailed enough to provide a concrete sense of the historical volatility of those institutions. Modern scholars of Sung divide the dynasty into three broad periods: (1) early Sung through 1082, (2) a period of “innovation” that began with the Yüan-feng reforms of 1080–2 and ended with the fall of Northern Sung in 1127, and (3) the Southern Sung. This gross periodization conveys little sense of the vibrant, fluid nature of Sung political life, yet does underscore the importance of the Yüan-feng reforms, a vital turning point in the history of Sung institutions.

Yet the reader should be forewarned: virtually every general statement in the following pages can, upon further examination, be modified in some way. For example, Sung officials wore purple, scarlet, and green robes. Well, yes, after 1082. Before 1082, they wore purple, scarlet, green, and blue robes. Sung political institutions, like all human creations, were in a constant state of flux. The detailed exposition of the evolution of these institutions, utilizing the full range of available sources, would be a gargantuan undertaking and has yet to be attempted, even by Chinese scholars.24 With these caveats in mind this description of Sung government and politics begins.

The unfinished character of the Sung state

In at least two ways, the Sung began differently than other major dynasties in Chinese history. First, when Chao K’uang-yin (T’ai-tsu, 927–76, r. 960–76), a palace guard commander in the service of the Later Chou (951–60), usurped power in 960, he began his dynasty not with a great conquest or an epic struggle against oppression but with a furtive palace coup against a seven-year-old child emperor. This inauspicious beginning haunted his image-conscious successors. Almost ninety years later, an angry Emperor Jen-tsung (r. 1022–63) dismissed an official whose mere poetic allusion to these events Jen-tsung construed as slander of the founding ancestor.25 So the Sung began more as a whimper than as a grand event, and there was little in 960 to suggest that the latest military coup would produce anything more than a sixth in the string of five short-lived dynasties that had followed the T’ang.

Second, neither the Sung founders nor their successors ever completed the conquest of all the traditional Chinese lands listed in the Shu-ching (Book of documents) as part of the original Chinese polity. After repeated Sung efforts to recover these areas, the 1005 treaty of Shan-yüan finally acknowledged Khitan control over the so-called “sixteen prefectures,” a large swath of territory south of the great wall that extended from Tatong in modern Shansi east through modern Peking to the coast.26 Furthermore, the Tangut state of Western Hsia (1032–1227) in the northwest controlled the Ordos region within the bend of the Yellow River (Huang-ho) and the modern Kansu corridor. The Han (206 bc–ad 220) and the T’ang had firmly controlled all these areas. And after 1127 the Jurchen Chin dynasty (1115–1234) took control of all territory north of the Huai river (Huai-ho). Sung failure to re-exert Chinese control over these areas was a constant source of wounded pride and a driving force in domestic politics. For example, according to one source, Emperor Shen-tsung adopted the New Policies (Hsin-fa) to raise the money necessary for military conquest of the sixteen prefectures.27

Although a series of treaties between Sung and its neighbors usually prevented overt hostilities, the north and northwest borders were always insecure and required the presence of large standing armies for defense. Unlike other dynasties that had relied on civilian militias conscripted from the peasant population, the Sung maintained paid professional armies. For most of the Northern Sung, the state financed a standing army of 1 million soldiers, from a general population of 60 million people. Military expenses for pay, supply, and armaments regularly consumed 80 percent of the entire state budget.28 Periods of open hostility, such as the Tangut wars in the 1040s, produced large government deficits and economic instability, and unleashed domestic pressures that roiled the political establishment.

The Sung was unlike the Han and the T’ang in yet another way. The Sung had no trial run. Short-lived yet strong dynasties (the Ch’in, 221–207 bc, and the Sui, ad 581–617) had preceded both the Han and the T’ang. These dynasties, although brief, had accomplished military consolidation and laid down institutional and administrative frameworks that their successors readily adapted. The Sung founders were not so fortunate. Tenth-century Sung government was a hopeless patchwork of late T’ang administrative structure and ad hoc provincial institutions inherited from the military governors of the Five Dynasties. These facts explain much of the tentative nature of early Sung political life. There was constant tension between the need to keep old political institutions functioning and, simultaneously, the need to develop new institutions better suited to changing times.

Traditional Chinese scholarship has focused on two catchphrases to explain the transformations the Sung founders brought to Chinese government, and these slogans still frame many studies on early Sung history, especially in China. The first, ch’iang-kan jo-chih (strengthen the trunk and weaken the branches), refers to early unification and centralization, the trunk being emperor and court, the branches being the provinces. The second, chung-wen ch’ing-wu (emphasize the civil and de-emphasize the military) refers to government by civil rather than military authority. Recent research suggests, however, that although the first was perhaps a conscious policy of T’ai-tsu (r. 960–76), the second did not begin until the reign of T’ai-tsung (r. 976–97), and that neither slogan, pushed to its extreme, describes the reality of early Sung.29

The development of mature Northern Sung political and governmental structures was a gradual process, and, in many ways, a process that seems to have unfolded largely without a unified vision. T’ai-tsu centralized financial and military structures because there was no other way for him to integrate and govern his rapidly expanding empire. He was a superb soldier who turned out, in addition, to have had a genius for administrative organization. T’ai-tsung drastically increased official recruitment through civil service examinations because he needed a homogeneous, dependable workforce to staff the new empire. Perhaps also, like Empress Wu of T’ang (r. 684–705), who inaugurated the examinations to recruit officials loyal to her, T’ai-tsung saw the benefit of forming a pool of new officials loyal to him rather than to his older brother, with whom he had had a difficult relationship.

Later Sung sources often refer to tsu-tsung chih fa (the policies of the ancestors) as a homogeneous body of foundational principles and institutions laid down by the dynastic founders, T’ai-tsu and T’ai-tsung. In truth, many of the “policies of the ancestors” did not emerge until the end of Chen-tsung’s or even the beginning of Jen-tsung’s reign, roughly the period from 1015 through 1035.30 For example, the beginnings of the Censorate (Yü-shih t’ai), an institution central to mature Sung government, did not emerge until the second decade of the eleventh century. Its division of labor with the Bureau of Policy Criticism (Chien-yüan) dates from 1017, but the two organs were probably not fully staffed until the early 1030s.31 Likewise, the Sung inherited a Directorate of Education (Kuo-tzu chien) from the Latter Chou, but this institution was not expanded and given its central role in the Sung educational system until 1044.32

At the same time, many early institutions and procedures that became later fixtures of Sung government arose in an ad hoc manner, the result of individual boldness and quick initiative. And given the Chinese veneration for precedent, once a thing was done, it became much easier to do a second time. A good example is the late eleventh-century account of the first use of chiao-huan (“to surrender and return”) power by the chung-shu she-jen (Secretariat drafter). In its mature Sung form, this practice empowered the drafter, a Secretariat official responsible for crafting polished versions of imperial edicts for promulgation, to return the emperor’s draft if he thought the draft contained errors or improprieties. In the T’ang, this power had been confined to the Chi-shih chung (Supervising Secretary) in the Chancellery, and had never been exercised by a Secretariat official. In the early Sung, although the post of Supervising Secretary in the Chancellery survived, that official had long been stripped of his power to “return” imperial drafts.33

In the late 1030s, Emperor Jen-tsung enfeoffed the wife of the nephew of the Dowager Empress Liu (969–1033) with a patent of nobility that afforded the woman, née Wang, a large salary and access to the palace. But her status was revoked when rumors circulated that she had been intimate with the emperor. After a short absence, however, she was once again seen within the palace. Protests from the Censorate to the throne on the matter were not returned. Soon thereafter the Secretariat received an imperial draft that reinstated her patent of nobility. Fu Pi (1004–83), then serving as Secretariat drafter, returned the emperor’s draft, essentially refusing to promulgate the order of reinstatement. The emperor backed down, no doubt fearing that the more he pushed the issue the more his affair with the woman would become public. Fu Pi adroitly used this leverage to establish a precedent for the drafter’s use of “return” power. He adapted a defunct T’ang procedure from the office of Supervising Secretary and boldly took advantage of the circumstances to extend that procedure to the office of Secretariat drafter, which he then occupied.34

The mid-eleventh century, roughly the period from the end of the Tangut wars in 1045 through the ascension of Emperor Shen-tsung in 1068, marks one of the most innovative, creative, and imaginative in the entire history of Chinese political thought and institutions. Southern Sung historians looked back to this quarter-century as the dynasty’s golden age. There is much to justify this view. First, by this period much of the institutional structure of Sung government was in place, but not so firmly in place that adaptation and change could not occur. Distinctive Sung institutions, like the Bureau of Policy Criticism and the drafter’s “return” authority, had emerged yet not ossified. This fluid framework provided room both for theorizing about how government should work and for actual experimentation on real institutions.

Second, much of this period coincides with the reign of Emperor Jen-tsung, the first emperor born and raised after the advent of shih ta-fu government in the early eleventh century. Later historians agreed that Jen-tsung knew how to be an emperor, and his posthumous name, “the benevolent ancestor,” speaks to qualities of openness and tolerance that contributed much to the spirit of the age. An important achievement of this period was an initial Sung dialogue on the proper relationship between sovereign and minister, between the emperor and his top advisers. Jen-tsung both allowed that dialogue to take place and took an active part in it, such that later continuations added little to the initial conversation. Third, there were just enough problems in this period to make devising solutions an urgent matter. The failed minor reforms and the budget deficits from the Tangut wars in the early 1040s forced an urgency on government thinkers and planners that earlier, more settled times had not provided.

Lastly, the shih ta-fu that T’ai-tsung first recruited through examinations into the civil service now formed a large and cohesive body of officials. Many shih ta-fu families had now produced two and three generations of officials. For the first time in Chinese history, large numbers of “literati” (shih) held posts high enough in the bureaucratic structure to actually effect policy. It is one of the great myths of Chinese history to describe the ruling elite as “Confucian literati.” For much of Chinese history those closest to imperial power were neither Confucian nor literati. But in the Northern Sung, for the first, and probably for the last, time, men like Fu Pi, Ou-yang Hsiu (1007–72), Ssu-ma Kuang (1019–86), and Wang An-shih, all both Confucian and literati by anyone’s definition, actually did play a significant role in ruling China. The tentative order they created quickly evaporated into divisive partisan feuding and authoritarian rule. But their brief moment was so attractive to later generations it gave rise to the myth that such people always had ruled, and the hope that they always could rule, China.

The literatus as civil servant

A great scholar has written: “Confucianism in China is a relatively modern thing.”35 Jacques Gernet argues that the “Neo-Confucian revival” of the eleventh century was in fact more new than revival. For Gernet, the image of continuity in the Confucian tradition, extending from Confucius (551–479 bc) through the Northern Sung, is a chimera created by scholars who divorce the intellectual content of Confucianism from its surrounding historical context. In other words, we should take quite seriously the T’ang writer Han Yü (768–824) when he tells us that the Confucian tradition of this time was moribund in a society dominated by Buddhist and Taoist values and institutions. Han Yü’s image of a Confucian-based civil service whose members would enjoy a modicum of real political power seemed, in theory and practice, a pipe dream to his eighth-century contemporaries. To Ou-yang Hsiu in the eleventh century, who discovered and rehabilitated the forgotten T’ang author, Han Yü’s vision seemed a lot like what Ou-yang Hsiu and his contemporaries were trying to create.36 Before the Sung, there had been many Confucians in China, perhaps even among emperors and the powerful. Much of state ritual and many state institutions derived from theoretical models in the Confucian classic texts. But, as Han Yü insisted, the essence of Confucian teachings, as contained in the Analects (Lun-yü) and Mencius (Meng-tzu), is a code of personal morality and a conviction that government is the extension of that personal code to the public sphere. No government in China had ever attempted to create actual working institutions that, in both theory and practice, embodied the personal moral standards of Confucian teaching. The eleventh-century attempt to do precisely this was something new.

At this point, a word of clarification concerning terminology may be in order. The Jesuit missionaries adapted the Latin term literati, plural of the singular literatus, to designate in a general way the educated ruling elite of sixteenth-century China. This term stressed the common literate culture these officials supposedly acquired through preparation for the civil service examin-ations, in contrast to the often semi-literate aristocracy of the Jesuits’ native Europe. The term “literati” – its origins and its connotations – are thus Western and neither translate nor describe any specific Chinese term or institution. In the Sung, shih ta-fu referred to all graded officials, of which there were about 40,000 in late Northern Sung.37 But many of these officials, especially those in the lower ranks of the military bureaucracy, never sat for examinations and were barely literate. Neither their background nor their educational profile conforms to earlier or modern Western notions of a literatus. Among the total number of all graded officials, about 3,000 were civilian “administrative-class” officials (ching-ch’ao kuan). In 1213, about 40 percent of this group, or 1,200, had passed the examinations and were highly literate. These officials staffed the upper levels of the civilian court administration and served in top provincial posts. In Sung usage, the term shih ta-fu sometimes refers in a general way to this elite group within the general bureaucracy. From these 1,200, about two dozen at any one time served in court positions that afforded them regular participation in the decision-making process. It is thus not proper to think of all Sung officials as literati, nor to equate literati with shih ta-fu in general. Literati, as used in this chapter, refers to civil officials who served in these upper ranks of Sung government. Most Sung writings on political theory and practice, especially in the Northern Sung, emanate from this group of people.38

The literati government of Northern Sung was firmly based on an examination system adapted from T’ang antecedents.39 But, although the mechanics of the two systems functioned in similar ways, their use and their effect on the two societies were totally different. The T’ang system produced about thirty chin-shih (presented scholar) graduates per year, most of whom were members of the existing hereditary aristocracy. These chin-shih were only a tiny fraction – according to one calculation 6 percent – of all T’ang officials. The T’ang examination system in fact served to fast-track promising members of the aristocracy into the top echelons of government, a government whose rank-and-file members qualified for office by attending schools or through military service. By contrast, the Sung examination system graduated on average about 200 chin-shih per year, and these graduates soon made up about 40 percent of “administrative-class” officials.40 Finally, in contrast to T’ang, the Sung examinations brought into government large numbers of those whose families had little or no record of prior government service.41

This altered role of the examinations in Sung produced a bureaucracy more broadly based than in any previous Chinese society. A standard and certainly valid component of the Naitō hypothesis was the contention that the Sung founders, especially T’ai-tsung, used the examinations as a recruiting mechan-ism to establish support for the dynasty among different segments of the popu-lation. A modern student of Sung government has suggested that the Sung civil service may even be viewed as a “representative” institution that parceled out power and status to different elements in the society, thus ensuring a wide range of support for the dynasty.42 There evolved, therefore, especially in the first hundred years of the dynasty, a literati government, comprising several thousand members who were more socially diverse, but more culturally and intellectually cohesive, than in the T’ang or before.

Literati ideas about government

Chapters elsewhere in this volume describe this literati culture in detail, especially its education and relation to intellectual and philosophical values. This section concentrates on how the full development of literati culture in the eleventh century generated a theory – if not a practice – of government that remained largely intact for the entire Sung period. It will describe how an extreme application of the same values that first generated and sustained this theoretical model frustrated its practical implementation, which came near to realization only for a brief period in the mid-eleventh century and perhaps again under Hsiao-tsung (r. 1162–89) in the Southern Sung.

Sung scholars, trained in the long tradition of Chinese allegorical commentary, liked to think in metaphors. One often finds in their writings two metaphors for government: the state is like the human body; the state is like a net. Early in 1069, Fu Pi had just been appointed Chief Councilor (tsai-hsiang). Too ill to attend court, he sent the young Emperor Shen-tsung, then twenty-one and only a year into his reign, a series of basic position papers on how government should operate. He began,

The proper way between a sovereign and his servitors is just to be a single body. The sovereign is the head. The members of the State Council are the arms, legs, heart, and backbone. The policy critics and censors are the eyes and ears. And all the other officials at court and in the provinces are the bones and joints, the tendons and muscles, the veins and arteries.43

Several months later, Ssu-ma Kuang used the same image of the state as a human body, and combined it with the metaphor of the net, to argue that Shen-tsung should not allow Wang An-shih to set up temporary administrative units that circumvented normal administrative procedure.

Why do we say government has a body? The sovereign is the head; the ministers are arms and legs. Top and bottom are linked together, court and province are governed together, like the ropes in a net, like the strands of silk.44

Both metaphors stress simultaneous co-ordination and subordination among hierarchical units of government. Su Hsün (1009–66) developed the net metaphor to describe the Sung relation between court and province. According to Su, the Sung achieved a balance between the overly permissive attitude toward regional power of the ancient Chou dynasty (1146–256 bc) and the authoritarian centralism of the ancient Ch’in: “In our Sung system of government – county (hsien), prefecture (chou), and circuit (lu) officials – the large link together the small, such that the ropes draw the strings together, and all unite at the top.” The image is one of a purse seine, where the larger ropes provide structure and co-ordination for the smaller ropes, yet all work together for a common purpose.45 Both the metaphor of the body and that of the net are ancient, from the Book of documents (Shu-ching) and the Book of poetry (Shih-ching) respectively, but these Sung writers elaborate on the archetypal metaphors to describe contemporary institutions.46 Fu Pi adapts the former to apply to his conception of the four major units of Sung government: monarch, ministers, censors (yü-shih), and other officials. Su Hsün uses the latter to describe what he believes is a unique Sung solution to the problem of center and province.

The Fu Pi and Ssu-ma Kuang texts from which these metaphors derive are long tracts that laid out for Shen-tsung the essential principles of Sung government. Both were written to warn against the rise of Wang An-shih, and both became classics, often included in Southern Sung anthologies. Ssu-ma’s text is entitled T’i-yao lun (Discourse on the essentials of the body). The graph t’i, sometimes expanded to kuo-t’i (the state body), here represents something close to the English concept of the “body politic” and occurs often in the mid-eleventh century to mean the totality of state administration and the principles that govern it, or, in colloquial English, “the system.” We may draw upon these two tracts to describe the theoretical foundations of Sung government. There are four overlapping areas of concern: (1) for balance of function, (2) for openness, (3) for consensus, and (4) for due bureaucratic process.

The state-as-body metaphor derives from Chinese medicine. Both authors stress that a healthy body is ho (harmonious, in accord), a condition that prevails when all parts of the body are intact, perform their own function, and act in consort with each other. Any element that is either weaker or stronger than it should be produces an imbalance in the system and leads to illness and incapacity. A key principle of Sung government was this notion of a balance of function, either among its three major decision-making units – monarch, ministers, and censors – or within the major units themselves. The Southern Sung official Lin Li (chin-shih 1142) wrote that “the sovereign has the power to govern, the ministers have the power to examine, and the censors have the power to critique.” Power in this case is ch’üan, literally the weight or counterpoise of the steelyard balance still commonly used today in rural Chinese markets to weigh small amounts of commodities. For Lin Li, an administrative imbalance occurred when any of the three elements of government became “heavy” and outweighed its counterparts. He argued that Emperor Hsiao-tsung, in an attempt to counteract a previous period when the “weighted minister” (ch’üan-ch’en) Ch’in Kuei (1090–1155) had dominated the court, had overweighted the monarchical function. Lin claimed that the emperor had abrogated to himself and to his minions certain functions that properly belonged to officials who occupy ministerial positions: Hsiao-tsung’s actions thus disturbed the balance of the body politic.47

One must emphasize that Sung scholars conceived of this balance as a balance of function, not as a balance of power in the same sense that the US Constitution divides power among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of American government. As we shall see below, in theory, all power in Sung government was vested in the monarch, who was the only ultimate source of authority. The power of any official to undertake any action derived from power that the emperor delegated to him and that the emperor could revoke at any time. However, as the metaphors imply, the function of the head is to co-ordinate the actions of the other parts of the body, not to attempt physically to perform their actual functions. The imperial will (sheng-chih), expressed as a written edict, is the vehicle through which the emperor rules. Yet, in order to eliminate error and forge consensus, a complex system of checks and correctives subjects the imperial will to oversight and review. The classical division of function among the Three Departments (San-sheng), into which the central Sung administration was divided after 1082, speaks precisely to this issue: “the Secretariat obtains the imperial will; the Chancellery resubmits the memorial; the Department of State Affairs (Shang-shu sheng) promulgates the action.”48

There is no Chinese term that conforms to the notion of “openness.” Yet this word may subsume a variety of ideas that center on the traditional Chinese opposition between kung (impartiality, public-mindedness) and ssu (partiality, private-mindedness). This opposition, likewise, derives from the earliest Chin-ese texts, the Book of documents and the Book of poetry, but Sung government was the first to use the value of impartiality as a base for creating discrete public institutions. An early formulation of the ideal comes from the Shih-chi (The grand scribe’s records) by Ssu-ma Ch’ien (c.145 bc–c.86 bc): “If you have something to say that concerns the public interest, say it in public; if you have something to say that concerns a private interest, the king does not receive matters of a private interest.”49Sung political thinkers put a high value on kung-i (public opinion) and tinkered endlessly with ways to incorporate public opinion into the decision-making process. One should emphasize that kung-i does not mean “public opinion” in the modern English sense of the expression. It means a consensus of what upper-echelon literati officials believed to be the best course of action on a given issue.

In 1065 Ssu-ma Kuang came close to arguing that public opinion, gathered and expressed through the mechanism of consultative assemblies (chi-i), might trump the authority of the emperor. Such assemblies of top court officials convened upon order of the emperor throughout the dynasty to discuss major policy issues. They produced written decisions and voted on the final draft of the document to be transmitted to the emperor.50 Ssu-ma writes that since human beings and Heaven (t’ien) share similar natures, then the will of the majority must represent what Heaven wants. He does not argue that what Heaven wants is always the best course of political action, simply that the emperor, who is inferior to Heaven, has the obligation to listen to the moral authority of Heaven, expressed as majority opinion.51 The 1069 tracts of both Fu Pi and Ssu-ma Kuang argue that the sovereign should not make appointments based on his own personal preferences, or the opinions of a few close advisers, but must do so only after a wide solicitation of opinion confirms the soundness of his own choices.

The Censorate and the Bureau of Policy Criticism – the eyes and ears of the body politic – were the major organs through which public opinion was to be funneled into court decision making. These institutions did not begin to assume their mature role in Sung government until the 1030s, but Ou-yang Hsiu immediately recognized their potential for giving the literati a major voice in court affairs. In 1034 he wrote a letter of congratulation to Fan Chung-yen (989–1052), who had just been appointed a remonstrant. Ou-yang wrote that, since the official rank of a remonstrant was not high, common thinking considered the position insignificant. But, Ou-yang argued, all other positions, save that of chief councilor, confined officials to speak only on matters related to their specific charge. “The remonstrant relates to every issue in the empire and to public opinion for all the age…and although low in station, he ranks therefore on a par with the chief councilor.”52 At the end of the century, writers looked back with awe and nostalgia at the power of the mid-century remonstrant to channel public opinion against higher authority. In 1086, the Censor Liu Chih (1030–97), after writing numerous memorials in an effort to dislodge the Chief Councilor Ts’ai Ch’üeh (1037–93), remarked – no doubt somewhat rhetorically – “never since the founders has a member of the State Council who went against public opinion failed to resign his position after even one accusation from a Censor or remonstrant.”53

The concern for consensus arose as a corollary to the concern for public opinion in decision making. The medical value of “harmony” (tiao-ho) required that, after consultation and discussion, all officials should support the final decision, which became at that point a formalized expression of the imper-ial will. The 1069 memorials of both Fu Pi and Ssu-ma Kuang insist that the government can only be harmonious when the monarch exercises decisively his authority to forge a consensus. Ssu-ma Kuang informs Shen-tsung that in Han times lower-level officials universally supported imperial decisions because these were issued in the name of the chief councilors after wide consultation. At present, however, Shen-tsung’s indecision has led to a condition where “officials endlessly attack each other with clever screeds and smart talk” and push their private agendas.54

The Sung concern for formal consensus manifested itself in many ways. Most obvious was the requirement that edicts and formal pronouncements, theoretically the product of consultation and consensus, be signed by all responsible officials before they could be validly promulgated. There are many references to such requirements, especially in the late Northern Sung period. For example, Liu Chih insists in 1086 that proper protocol had always required that all senior Secretariat–Chancellery (chung-shu men-hsia) officials endorse appointment nominations from that agency, thereby to ensure “the harmony and consent of all involved.”55 Secretariat directives required the signatures of all chief councilors and assistant chief councilors.56 Imperial edicts (chao-tz’u) required the signatures and seals of State Council members, as well as those of the supervising officials of the lower agencies involved. One of the rare surviving original copies of a Sung dynasty edict concerns a local Shan-hsi dragon deity who was ennobled in 1110 for his assistance in ending a drought. The document is signed by sixteen officials, including all six members of the State Council, the two supervising officials of the Ministry of Personnel, and three clerks. There are forty-three seals.57

A concern for due bureaucratic process, in essence an insistence on the correct processing of documents, emerged as soon as large numbers of literati began to impact government in the 1020s and 1030s. Political writers insist that due bureaucratic process guarantees balance, openness, and consensus, and functions as a barometer of these other values. As we shall see below, the orderly processing of large numbers of documents was vital to both the audience (ch’ao) and the memorial systems. These mechanisms were the two central institutions of Sung decision making and generated the imperial edicts that provided the legal and regulatory foundations of Sung government. An elaborate set of interlocking bureaucratic procedures, aimed to protect the integrity of these documents, arose early in Jen-tsung’s reign and reached its most complex form in the 1080s. Sung political writers saw this system as a major defense against functional imbalance and authoritarianism, either from the emperor or from the chief councilors. Tirades against violations of due documentary process form a mainstay of Southern Sung political commentary and assume that a return to the Northern Sung safeguards will act as a bulwark against corruption and disorder.

In 1043, Ou-yang Hsiu, as part of a larger attack on the lingering influence of former Chief Councilor Lü I-chien (979–1044), charged that Lü had been submitting memorials in secret, using eunuch intermediaries to bypass the formal memorial process. Ou-yang states that since Lü is too ill to write such documents himself, his underlings must therefore be writing them under his name and so gaining illicit access to the emperor. Such short-circuiting of the memorial process forestalls “public discussion” and destroys the confidence and ability of other officials to perform their designated functions.58 As Ou-yang implies, an integral aspect of the memorial system was a division of function among the various offices through which the document passed, a division which allowed designated officials to verify and comment on its contents. The system created a series of ordered checkpoints through which the document had to pass. Specific officials had the power to put a “hold” (liu) on a document or “return it for correction” (feng-po) to the previous station.

Due bureaucratic process had two aspects that confound simple notions of Sung government as authoritarian. First, each office and each official had a specific duty to perform. Bypassing a checkpoint would invalidate the document and derail the resolution of whatever matter was at hand. Second, if an official refused to permit a document to pass his station, there was little remedy except to remove the official. Even emperors were reluctant to force a document past a station or to accept the validity of a document that had not been properly processed. An incident from the early years of the New Policies illustrates how these principles played out in real politics.

Early in 1069 Wang An-shih created the Chih-chih san-ssu t’iao-li ssu (Finance Planning Commission, literally Bureau for the Implementation of Fiscal Regulations) as a subunit within the Secretariat–Chancellery to co-ordinate financial planning for the New Policies. A separate office with its own staff, the bureau was to be headed by two officials: Wang himself, then serving as assistant chief councilor, and Ch’en Sheng-chih (1011–79), then military affairs commissioner (shu-mi shih). In the winter of 1069 Ch’en became chief councilor, abandoned the New Policies, and, refused to sign documents from the bureau, maintaining it was beneath the dignity of a Chief Councilor to do so. Emperor Shen-tsung suggested one simply abandon the bureau and that Wang and Ch’en could sign documents relating to fiscal matters in their capacity as supervising officials of the Secretariat. Wang refused. He insisted on the necessity of a separate bureaucratic entity to streamline the cumbersome document-flow procedures in the Secretariat. When Shen-tsung suggested that Wang simply head the bureau himself, Wang also refused, insisting that the purpose of the bureau was to co-ordinate fiscal matters between the Secretariat and the Military Affairs Commission (Shu-mi yüan). The matter was resolved by appointing Han Chiang (1012–88), then vice military affairs commissioner (shu-mi fu-shih), to the new bureau.59

This episode reveals several key points about Sung government. First, agreement among the signatory officials was necessary for a given agency to produce valid documents. In this case, Ch’en’s refusal to endorse documents effectively brought the bureau’s work to a halt. Second, although the emperor had the authority to enforce any solution, the primacy of the need for valid documents constrained him in many ways. In this case, Shen-tsung must either restructure the bureau, which Wang opposed, or replace Ch’en with another official. Simply ordering Ch’en to sign the documents seems not to have been a viable option.60

This literati urge for due process conflicted with the theory of absolute imperial power. From the beginning of the dynasty, but with increasing frequency toward the end of the eleventh century, the monarchy issued “directed edicts” (chung-chih, nei-chiang, nei-p’i). These were various imperial pronouncements – not generated in response to a submitted memorial – that could be issued in the name of the emperor or empress directly to the relevant agency. The most famous of these were the so-called yü-pi shou-chao (imperially brushed handwritten edicts) often used during Emperor Hui-tsung’s reign at the end of the Northern Sung. Various emperors chose to route such “directed edicts” through the Secretariat, thus subjecting them to literati oversight, but other emperors did not do so. The use of “directed edicts,” often written and issued by members of the palace without the emperor’s knowledge, was a constant sore point in the relations between emperor and literati. In 1132, Emperor Kao-tsung (r. 1127–62), in order to distance himself from the policies of Hui-tsung and to generate literati support for his fledgling administration, ordered a return to the routine review process for edicts. He ordered that all edicts pass through the Secretariat and be subject to its oversight procedures. Chief Councilor Chu Sheng-fei (1082–1144) pushed the matter a step further, insisting that “if a text does not pass through the Secretariat and Chancellery, it cannot be considered an imperial order.”61

In Southern Sung there was a popular and probably apocryphal anecdote about Emperor Jen-tsung. Someone, by implication a eunuch or other member of the palace, encouraged Jen-tsung to “just take hold of power and don’t let these ministers play with your majesty and your revenue.” Jen-tsung declined. He argued that the exercise of unilateral power would provide no possibility for him to correct mistakes. Submitting decisions to “public opinion,” allowing the ministers to implement and the censors to critique, made correcting errors easy.62 This text represents the idealized Southern Sung literati vision of what the Northern Sung was like. The reality, of course, was much different. But the vision persisted to the end. In the final years of the dynasty, a 1267 memorial from the Censor Liu Fu (1217–76) noted that over half the appointments listed in the latest administrative gazette had been done through “directed edicts.” He concluded, “orderly government is what proceeds through the Secretariat; disorderly government is what does not proceed through the Secretariat. The world’s matters should be shared with the world; they are not the private domain of the ruler.”63

The literati character of Sung government

The rulers did not always hold similar views. Rare survivals of imperial dissatisfaction with the literati as administrators afford glimpses of the large gap between theory and practice. Emperor Hsiao-tsung often complained to his chief councilors about defects in the literati character. He found them overly given to “lofty theory” and little inclined to discuss such practical matters as agriculture or finance. They routinely put the affairs of their own families over the interests of the state and did not understand that the Classics were all about economics.64 Hsiao-tsung came to office in 1162 with a zeal to reform this officialdom he found so wanting. One of his first acts was to order circuit inspectors to submit daily performance evaluations for each prefect in their jurisdictions. There were seventeen circuits in Southern Sung, each with two inspectors who were ordered to compile these reports. There were about three hundred Sung prefectures. The emperor’s order would thus have required the submission and processing of almost 600 individual evaluations every day. As Li Hsin-ch’uan notes laconically, “the press of business made implementation impossible.”65 That even a novice emperor, as Hsiao-tsung was in 1162, could have contemplated such a measure underscores a prime feature of Sung government practice: its intensely written, bureaucratic character.

A comparison of the Compendium of Sung documents with its predecessor, the T’ang hui-yao (Compendium of T’ang documents) reveals the extent of Sung graphomania. The latter is a tidy work in 100 chapters. The last edition of the Compendium of Sung documents, completed by Li Hsin-ch’uan in 1236, ended with the year 1189 – still 100 years before the end of dynasty – and contained 588 chapters.66 This vast increase in surviving documentation did not occur because Sung is chronologically more recent than T’ang, or because of the growth of printing in the Sung, although these were certainly factors. It resulted from a profound change in how the court transacted business.

In T’ang and Five Dynasties, the chief councilors sat with the emperor over tea at the morning audience (ch’ao-hui) and discussed major issues of state. After the audience, the councilors personally drafted edicts that reflected the results of these conversations and then submitted the drafts to the emperor for approval. The councilors on their own authority decided lesser matters, such as legal and personnel actions, and drew up the relevant orders which the emperor subsequently endorsed. However, T’ai-tsu’s first councilors, because they had all worked for previous dynasties and were apprehensive of their new circumstances, insisted on drafting a cha-tzu (administrative memorial) on every matter, and presented these documents at audience to obtain T’ai-tsu’s reaction. After the audience, the councilors then drafted their version of the “imperial will” and – jointly signed by all councilors – this document was then resubmitted for T’ai-tsu’s final approval. This new procedure eliminated chances of misunderstanding but also removed the informality of the T’ang discussions between the emperor and his councilors. The process was also time-consuming, and the morning audience often lasted into the early afternoon.67

The court audience (ch’ao-hui) thus changed drastically in character from T’ang to Sung. The social distance between the emperor and his ministers increased. To compensate, there was an increased reliance on the written text, and court procedures became more formalized and bureaucratic. Without wishing to push the analogy too far, at its highest level Chinese government turned from something like a corporate board meeting into something like a real-estate closing, from a policy discussion to a bureaucratic paper shuffle. In time, the results of this turn developed into the torrent of documentation whose remnants the Compendium of Sung documents now contains.

Modern scholars, Chinese and Western, usually describe the eleventh-century rise of literati culture in generally positive terms. The Sung shih ta-fu themselves were not always so generous. The eleventh century saw not only a rise in the political relevance of literati culture but also an immediate crisis in the viability of that culture. In the T’ang, an anthology known simply as the Wen-hsüan (Literary selections) was the basic preparation manual for the chin-shih examinations. The work has 100 chapters. Its Sung continuation, the Wen-yüan ying-hua (Blossoms from the garden of literature), completed in 987, has 1,000 chapters. In short, the amount of prior writing that literati were expected to control proliferated beyond the capacity of all but the most gifted to master.68 By Southern Sung, this crisis had brought about fundamental changes in reading and studying habits, new commentaries on the Classics, new educational institutions such as private academies, and the growth of private printing. It is also directly related to the graphomaniac character of Sung administration and to the culture of the Sung bureaucrat.

During the military crisis at the end of the Northern Sung, Teng Su (1091–1132) observed that the Jurchen army enjoyed a number of advantages over the Sung. The Jurchen were better able to control their troops because “their written communications are brief and fast; ours are prolix and slow.”69 Chu Hsi also frequently criticized the delays and bottlenecks that plagued Sung administration and bemoaned the contemporary excess of “empty paperwork.” He once saw a Military Affairs Commission dossier from the T’ai-tsu era and praised the “speed and simplicity” of its documentary process. His own age, he lamented, required three levels of administration and a chief councilor’s approval to appoint a minor functionary to hold a lamp during the emperor’s visits to the ancestral temple.70

A major reference work contains separate entries for 117 different kinds of edicts, orders, declarations, decrees, rescripts, memorials, petitions, notes, interoffice memoranda, and other assorted bureaucratic documents.71 In addition, as we shall see below, the operation and maintenance of the Sung civil service system also required the production and preservation of vast amounts of written documentation. Control over this documentation was vital to the exercise of power in the Sung state. As the example of Wang An-shih and Ch’en Sheng-chih makes clear, administrative success was uncertain at best, impossible at worst, unless one could ensure the movement of relevant documents past bureaucratic checkpoints. Since one way to control the progress of documents was to control those personnel appointed to the stations through which they were required to pass, administrative procedures originally designed to promote openness eventually fostered secret deal making and faction building.

Control over current documents was not enough. Exercise of power in Sung China also required control over past and future documents; that is, over archives and the writing of history. Through the Northern Sung period, the State History Office (Shih-kuan) was located next door to the office of the chief councilors, and the senior chief councilor (shou-hsiang) was usually appointed concurrent director of the History Office (t’ung-hsiu shih-kuan hsiu-chuan). Given the overriding concern for precedent in Chinese decision making, access to documents that recorded prior decisions was crucial to the generation of present policy. The writing and rewriting of history thus became a continual process, a natural extension of the audience and memorial systems. Struggles over access to past documents and the changing interpretations that political movement brought to these documents were often at the center of factional infighting, especially in the late Northern Sung. An example from that period – a brief history of the so-called Su-li so (Office of Accusation Adjudication) – may illustrate this point.

In 1068, Wang An-shih began a tactic of using legal proceedings to remove his opponents from office.72 During the period from 1068 through 1085, therefore, many officials were accused and convicted of crimes that related to their opposition to the New Policies. With the change of government in 1086, the Office of Accusation Adjudication (Su-li so) was established to clear these officials of the former charges. Those who could prove that extenuating circumstances or personal grudges had motivated their accusers were invited to petition the office to have the offense legally removed from their records. These petitions naturally contained details of the former “crimes” and the refutations were often phrased in language critical of the New Policies. Twelve years later, in 1098, with advocates of the New Policies now again in control, these docu-ments from the now defunct office were used to reopen judicial cases against the same officials the office had previously cleared. The emperor appointed two censors to review the dossiers and ordered that “the name and position of any official whose original disposition or whose documentation submitted to the Office of Accusation Adjudication contains language disrespectful to the former court shall be reported.” The diary of Tseng Pu (1035–1107) records that 897 officials were “rectified” in this way.73

As this example implies, political factions (tang), which formed as soon as the government assumed its distinctive literati cast in the early eleventh century, were a prominent feature of Sung political life. Although earlier and later dynasties also had political factions, their Sung manifestation is famous for its persistence and its degree of integration into Sung political structures. Some scholars trace the beginnings of modern political parties to the Sung factions, and some aspects of this comparison may be valid. But the Sung factions were fluid arrangements, basically extensions of the older T’ang factions, loose alliances centered around powerful political personalities. Membership was always unstable, even for short periods of time. Although a given intellectual or political agenda was often present, the strength of a Sung faction depended primarily on the political skills of its leader. Also, because factions were almost always defined publicly in negative terms, there was never public acknowledgment of membership. Formal membership lists were compiled only in the negative counterexample, where one faction endeavored legally to prosecute its opponents. No one, even the leader, could always be sure who was in or who was out. This ad hoc nature was only one of many factors that prevented Sung factions from developing into political parties.74

As in modern China, Sung political factions are perhaps best studied as patronage associations. The leader’s ability to hold the group together depends on his continued ability to generate positions, promotions, preferments, contracts, and contacts for its members. Several features of the Sung civil service itself fostered the development and persistence of factions. Sponsorship endorsements for promotions (chü-chu), where a senior sponsor guaranteed the behavior of a junior, and “protection privilege” (yin), where senior officials could grant civil service entry to younger kin, both contributed to faction formation. Social factors were also involved. Officials often took younger scholars into their houses as “house clients” (men-k’o) where the clients acted as tutors, secretaries, or copyists. As the official career of the client developed, his relationship with his patron remained. Under certain circumstances, it was even possible for a senior official to use yin privilege for a house tutor. Also, upper-echelon literati maintained very large immediate families. One official might often support a household of forty or more individuals who lived together.75 And literati families often intermarried. Given these large family structures and extensive intermarriage, many top officials, especially in Northern Sung, were related to each other through marriage. Although modern scholars seldom detect simple correlations between faction and family, Emperor Hsiao-tsung knew whereof he spoke when he complained that the literati put their families before the state.

The Sung factions also never became political parties because literati culture never developed a neutral vocabulary to refer to the political opposition. Loyalty to a political superior, especially to the sovereign, was a paramount Chinese virtue. But the concept of a loyal opposition was anathema to the ethical absolutes of texts such as the Analects and the Mencius, the new mainstays of Sung Confucian orthodoxy. A key eleventh-century development in Chin-ese political discourse was the adaptation of the old Confucian terms chün-tzu (gentlemen, superior men) and hsiao-jen (small men, inferior men) to refer to contemporary political figures. Although originally not without political overtones, in the old texts these terms referred primarily to individuals who had successfully or unsuccessfully developed their inner natures according to a prescribed regimen of Confucian moral cultivation. Beginning with the advent of literati culture in the 1020s and 1030s, however, Sung writers began to employ these terms in contemporary political discourse to label themselves (as chün-tzu) and their opponents (as hsiao-jen). By the 1050s, this distinction had entered the basic vocabulary of political discourse. The importance of this rhetorical development cannot be overestimated. The distinction helped to fuel the intense factional politics of the late Northern Sung and became a central fixture of Tao-hsüeh political rhetoric in the twelfth century. By the thirteenth century, Tao-hsüeh teachers had formulated a history of the entire dynasty based on their own determination of who had behaved as chün-tzu and who as hsiao-jen. And these judgments form the basis of much of the official Sung history of 1345.

The distinction also became the basis for defining the role of the emperor in Sung government. Fu Pi’s 1069 memorial to Shen-tsung links political disharmony directly to the court’s simultaneous employment of chün-tzu and hsiao-jen. The emperor’s role is to distinguish between the two and so remove the cause of disharmony. Ssu-ma Kuang made the same point, arguing that the function of the sovereign is “to distinguish the straight from the oblique.” Both authors stress that the emperor should employ “public opinion” to help him make these distinctions. This rhetoric was applied here against the rise of Wang An-shih, but the imperial injunction to “distinguish” became the legal justification for the factional purges of the early twelfth century and after.

The rhetoric of “distinction” was also applied retroactively. The most famous factional episode in earlier Chinese history had been the so-called Niu–Li controversy (Niu Li tang-cheng) in the ninth century.76 In his Tzu-chih t’ung-chien (Comprehensive mirror that aids administration), Ssu-ma Kuang quoted the remark of Emperor Wen-tsung (r. 826–40) that it would be easier to rid the country of the Ho-pei rebels (Ho-pei fan-chen) than of the Niu (Niu Ch’eng-ju, 780–848) and Li (Li Te-yü, 787–850) factions. But in a long comment Ssu-ma put the blame for the problem squarely upon the emperor’s shoulders: Wen-tsung himself was to blame because he had failed in his duty to distinguish between chün-tzu and hsiao-jen.77 The adoption of this rhetoric of distinction as a principle of historical classification and analysis created enormous problems for the writing of contemporary history. Each change of administration required a wholesale revision of documents, since a new administration could hardly employ officials whom the emperor had formerly distinguished as hsiao-jen – hence the Office of Accusation Adjudication. With every change of administration after 1068, the chün-tzu became hsiao-jen and vice versa, and the practice of rewriting history continued well into Southern Sung. The official history of Shen-tsung’s reign, the Shen-tsung shih-lu (Shen-tsung veritable records) was revised five times between 1091 and 1138. One is reminded of Simon Leys’s observation that continual purges and factional realignments made the rewriting of the official history of the Chinese Communist Party so tedious that one eventually stopped writing it altogether.

The civil service system

Civil and military officials

It is common to speak in English of a “Sung civil service system.” But Sung officialdom differed in major ways from modern systems of professional civil service. First, the Sung system divided officials into two broad categories: civil (wen-kuan) and military (wu-kuan). The English term “Sung civil service” applies to all Sung officials, both civil and military, not just to the civil-side, or wen, officials. Second, Sung officials were not full-time employees in the modern sense. Most officials only spent about 50 percent of their careers in functional positions (ch’ai-ch’ien – often translated as “commission”). Half their time was spent actually working for the state, but a convoluted and time-consuming process of reassignment consumed the other half. This system generated long periods of downtime and also provided for sinecures between functional positions. The lengthy periods of voluntary and involuntary time off help explain the extensive and varied nonofficial activities of Sung bureaucrats. Some used this time to produce the copious amounts of literature and scholarship for which the period is renowned. Others devoted themselves to private business ventures that enriched themselves and their families. Many did both.

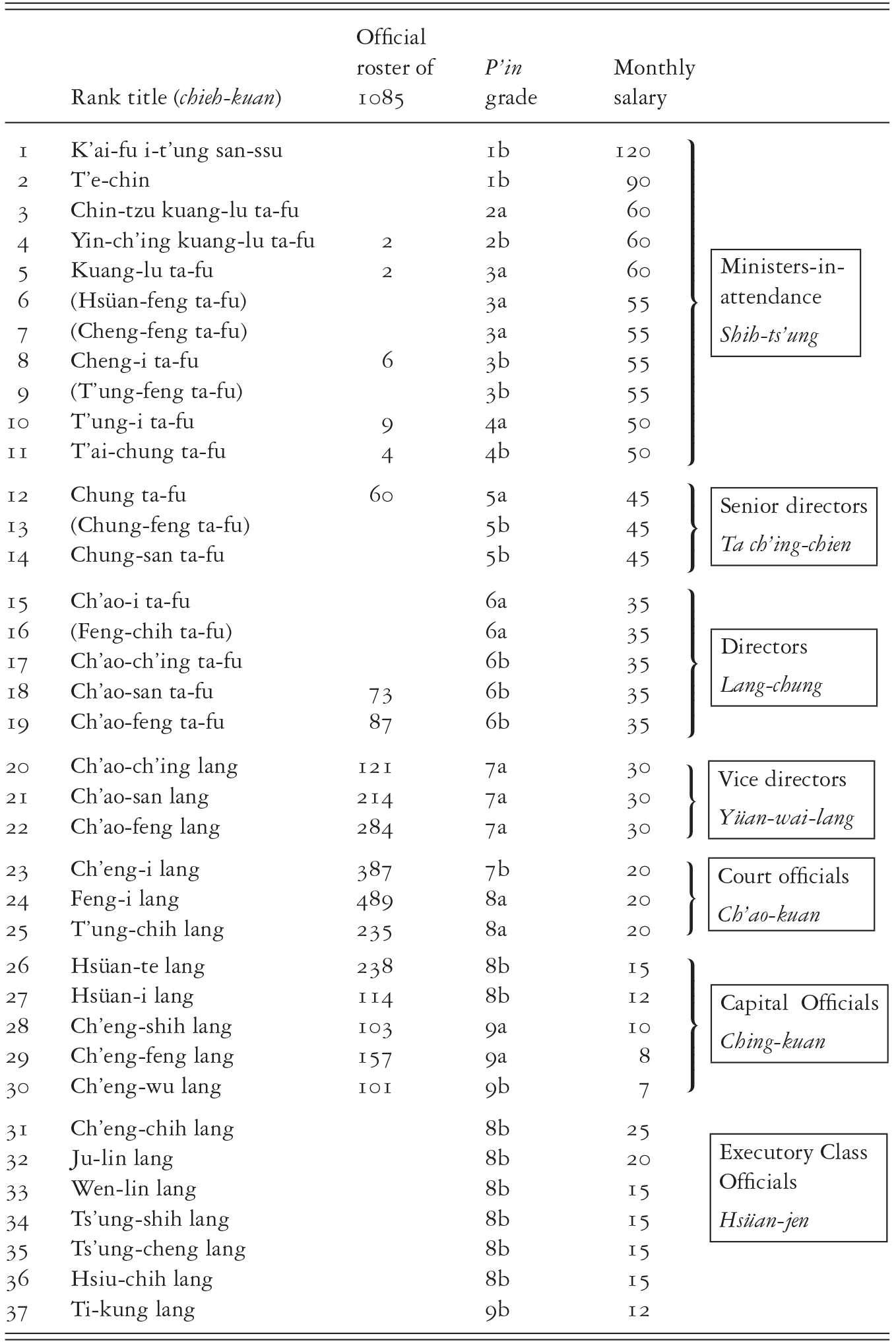

For the purpose of this chapter, “officials” will be defined as persons who held p’in (grade, rank, level) in the Sung personal ranking system for government employees. Such officials were called kuan-yüan in Sung parlance, a term usually rendered into English as official, functionary, mandarin, or bureaucrat. Sung society sharply distinguished between these graded officials and the lesser categories of ungraded government employees such as clerks and village officers, who in English are often referred to collectively as the “sub-bureaucracy.”78 The Censorate, in conjunction with other relevant central government agencies, kept an “official register” (pan-pu) of officials on active service. The register was updated quarterly and included all graded officials who either held office or were qualified to hold office. It excluded those who were retired, in mourning, or “disenrolled” (ch’u-ming) for misdeeds. Officials received formal “patents of office” (kao-shen) for each functional position to which they were appointed. Variously colored official robes (kuan-fu) visibly marked their status as officials as well as their position in the hierarchy (purple the highest, scarlet the middle, green the lowest). More importantly, government census records designated families headed by an official as “official household” (kuan-hu). This status carried significant financial and legal advantages, including reduction or remission of certain tax obligations, the right to use legal proxies that buffered officials from normal court proceedings, and immunity from corporal punishment.79

Formal court audience protocol emphasized the basic division of Sung officialdom into civil and military. As the emperor sat in formal audience and faced south, civil officials stood to his left on the east and military officials stood to his right on the west. Two separate systems of personal rank (kuan-p’in) – with different numbers of ranks and different names for the ranks in the two systems – also reinforced this division into civil and military. Furthermore, in the Ministry of Personnel, the appointment process for the two groups was divided into a “left selection” (tso-hsüan) for civil and a “right selection” (yu-hsüan) for military officials.