The history of musical comedy begins in confusion.1

Most histories of American musical theatre give short shrift – at best – to the ‘origin of the species’, to use Edith Borroff’s apt phrase. Despite lofty ambitions (titles that claim coverage ‘from the beginning to the present’), most authors are content to offer a brief essay about the antecedents of musical comedy, usually including definitive identification of ‘the first American musical’ (The Black Crook, Little Johnny Jones, Evangeline, Show Boat, The Beggar’s Opera, The Wizard of the Nile or any number of other works), before turning, with an almost discernible sigh of relief, to musical theatre of the twentieth century. The reasons for the brevity and for the disagreement on the ‘first’ musical become readily apparent as soon as one attempts to sort out the myriad different types of musical theatrical forms that materialised, metamorphosed, became popular, disappeared, re-emerged and cross-fertilised prior to the twentieth century. To put it simply, for the scholar in search of a clear lineage to the forms of the twentieth century, musical theatre in the eighteenth – and even more so in the nineteenth – century was a tangled, chaotic mess. This was not the impression at the time, of course. To the contrary, a nineteenth-century American, especially the resident of a large city like New York, found musical theatrical life during the time to be gloriously rich, varied and ever-changing; it was a world that was entertaining, interesting, exciting and innovative to an extent that should elicit a twinge of envy from the modern reader. But the job of the historian is to clarify and attempt to put into some kind of order the messiness of a bygone era. And the richness of that period makes the job both difficult and important.

What follows, then, is a carefully guided and succinct tour of the American musical-theatrical world of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. To some readers – especially those anxious to reach the more familiar terrain of the twentieth century – the description of musical life of the earlier eras will be a little puzzling, primarily because this essay will describe genres that have since been removed from the general category of ‘musical theatre’. But the varied musical forms that Americans enjoyed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (including opera, pantomime, melodrama, minstrelsy and dance) developed, changed and influenced each other to a remarkable degree. The wealth of earlier musical styles evolved into the wonderfully diverse, rich and confusing jumble that was the American musical-theatrical world of the last third of the nineteenth century, which many scholars agree was the birthplace of the twentieth-century musical. It is important, then, to examine the whole picture – albeit in summary fashion – in order to comprehend the foundations of this truly American musical form.

The Eighteenth Century

There is scattered evidence of theatrical activity in the American colonies in the seventeenth century, but the real history of musical theatre commences in the eighteenth. The first opera mounted in English-speaking America was the ballad opera Flora, or, Hob in the Wall, performed in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1735; two weeks prior to that, the same theatre had offered a different work that was equally musical in nature: the pantomime The Adventures of Harlequin and Scaramouche, performed as an afterpiece.2 From the 1730s until the Revolution, Americans – especially those living in the urban centres of the Northeast or the market towns of the rural Southeast – witnessed a constant stream of theatrical offerings imported from the British Isles. Many thespians of this period were associated with itinerant or ‘strolling’ companies, formed by players (frequently family members) who performed in return for shares of the box-office take. Women performers, in particular, were all but obliged by the mandates of society to tour with male family members, in order to preserve any semblance of reputation already made suspect by public performance. The first such permanent strolling troupe in the colonies was Lewis Hallam’s Company of Comedians, which arrived from London in 1752, renamed itself the American Company and gave its first performance in Williamsburg, Virginia.3 This company and others like it travelled from town to town and city to city on regular circuits (primarily via horse-drawn vehicles) during the mid-eighteenth century; they eventually built theatres in larger towns from which they branched out – especially during the summer – to perform in smaller towns and villages located within a reasonable distance from the hub city. This modus operandi was similar to that in the British Isles, where London was the principal hub, cities like Manchester, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Dublin were smaller hubs, and other towns and villages were served by itinerant troupes that used theatres in the larger urban areas as seats of operation. To a great extent, then, strolling theatrical troupes active in America were transatlantic extensions of the provincial theatrical circuit of Great Britain; American theatres were essentially part of the London cultural sphere.

In 1774 professional theatrical activity in the colonies officially stopped (although dramatic performances continued, mostly under the guise of ‘concerts’), when the Continental Congress passed a resolution that prohibited activities that were distracting to the Revolution. After the war, the banished strolling companies resumed activities. Hallam’s troupe, now proudly called the Old American Company, returned from Jamaica in 1784, re-established its circuit and enjoyed a virtual monopoly until the early 1790s. During that decade American theatrical life underwent significant change, as urban areas in the new nation increased sufficiently in size to allow the establishment of permanent theatres with resident stock companies. Important theatres were built (especially in the 1790s) in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Charleston, Baltimore and other cities on the East Coast. Resident stock companies, complete with orchestras and musical directors, were hired; their performances frequently included the assistance of ‘gentlemen amateurs’, which reflects a continuing – and growing – active interest in the theatre among American city dwellers. Since theatres traditionally offered permanent work to musicians, this spate of theatre building helped to attract to America a whole coterie of musicians from Europe. These musicians – most of whom arrived in the 1790s – included Alexander Reinagle (1756–1809), Rayner Taylor (1747–1825), Benjamin Carr (1768–1831) and James Hewitt (1770–1827) from Scotland and England, Victor Pelissier (c. 1740/50–c. 1820) from France and Gottlieb Graupner (1767–1836) from Germany.

The repertory of all theatres during this period relied heavily on music; the historian Julian Mates asserts that by the beginning of the nineteenth century, fully half of the repertory on the American stage was musical in nature.4 Every theatre had an orchestra, and a typical evening, in the words of William Brooks, consisted of ‘an encyclopedia of entertainment, a potpourri of performance’, much of which required orchestral accompaniment.5 The evening’s activity generally commenced with a short concert of ‘waiting music’ played by the orchestra, followed by first a prologue and then the principal dramatic work (the mainpiece), which – in turn – was followed by a shorter work, usually a farce or pantomime (the afterpiece). Between the mainpiece and the afterpiece, the orchestra would play several selections, and during both dramatic works the actors would interpolate songs or dances as divertissements or changes of pace. The evening’s entertainment – which frequently lasted four or five hours – would conclude with diverse amusements such as singing, dancing, further works performed by the orchestra, or possibly a short epilogue; sometimes the choice of repertory was in response to requests from audience members.6 Audience behaviour at such entertainments was not unlike that typical of twentieth-century sporting events: members of the audience would come and go, eat and drink, talk among themselves, applaud wildly, heckle the actors mercilessly, or sing along with the performers. The ‘dramatic’ evening just described is one that featured a drama; when the mainpiece consisted instead of a ballad opera or a comic opera (both, on the American stage, essentially plays with songs), the percentage of music performed was even greater. It should be clear that during this period, the terms ‘theatre’ and ‘musical theatre’ were essentially synonymous.

For the most part, the American theatre during the final decades of the eighteenth century remained firmly British in orientation: American theatres became important competitors with provincial English theatres for actors, actresses, and even pantomimists, most of whom were French (but who arrived via England).7 Costumes and scenery were either imported outright or copied from productions in England, and theatrical repertory was also, by and large, from London – imported either as manuscripts, as prompt books or as published music in keyboard or vocal format.8 One of the principal tasks for a theatre’s musical director was the re-orchestration (frequently from keyboard reduction) of musical accompaniment to dramatic or operatic works; musical directors also composed new incidental music, and – increasingly – musical-theatrical works of their own. The most popular musical works performed on the American stage between 1790 and 1810, according to Susan Porter, included such standard London fare as the comic operas The Poor Soldier (1783) and Rosina (1782) by William Shield; The Children in the Wood (1793) and The Mountaineers (1793) by Samuel Arnold; and No Song, No Supper (1790) by Stephen Storace.9 During the last decade of the eighteenth century, however, American theatregoers could increasingly witness musical-theatrical works written in America, usually by the recent musical immigrants mentioned earlier. These included such works as Victor Pelissier’s Edwin and Angelina (1791); operas by James Hewitt (Tammany; or, the Indian Chief, 1794) and Benjamin Carr (The Archers, 1796); and music for pantomimes by composers such as Pelissier, Reinagle, Hewitt and Taylor. Melodrama (introduced from France by way of England) also became part of the American theatrical repertory in the 1790s; it would become one of the dominant forms of musical theatre in the nineteenth century. The music from all of these shows increasingly permeated American society by means of sheet music; it was both imported and published by American firms, snapped up from music store shelves, and played on fortepianos in American parlours all over the country.

The Nineteenth Century: 1800–1840

By the first decades of the nineteenth century, theatrical production in the United States was accomplished almost exclusively by established theatres with resident stock companies. Itinerant theatrical troupes (like the earlier ‘strolling’ players) were still active in the less settled parts of the country (and would remain so, moving ever farther west with the frontier); the ‘star system’, under which a visiting dramatic star (usually from England) would visit different theatres in turn, taking the starring roles of plays mounted by the stock companies, had just been introduced from Great Britain. For the most part, however, theatrical performances in Federal-period America were mounted by the stock companies of local theatres, with musical accompaniment by the theatres’ orchestras. For repertory during this period, American theatres for the most part continued to rely on London for their material. With an ever-growing critical mass of skilled actors, playwrights and composers resident in the United States, however, these imported materials, more frequently than not, were extensively modified (mostly in subject matter) for American audiences.

Melodrama

Melodrama, which would (arguably) become the most important and popular dramatic and musical genre in America during the nineteenth century, emerged in full force during the first decades. Originally a French technique from the mid-eighteenth century, melodrama – the use in drama of short musical passages to heighten emotional affect, either in alternation with or underlying spoken dialogue – came to America, as had pantomime, from the British popular theatre.10 The first melodrama presented in America was probably Ariadne Abandoned by Theseus in the Isle of Naxos, with music (now lost) by Victor Pelissier, performed in New York in 1797. Early melodramas used music quite sparingly; this, as we shall see, would change later in the century.

Few instrumental ‘melos’ (snippets of ‘hurry music’, ‘diabolical music’, ‘sorrow’, ‘pursuit’, etc.) survive from before 1850; it was rare for such manuscripts to be published, and most perished in the fires that regularly consumed theatres in the nineteenth century. But specific directions indicated in prompt books, in conjunction with information from the few scores that do survive, suffice to provide a clear indication of the nature of melodrama. Two early works merit some mention. Victor Pelissier’s complete orchestral score to William Dunlap’s The Voice of Nature (1803) is the earliest extant musical score for a complete dramatic work written for the American theatre.11 It includes several composed pieces (marches, a dance, choruses); musical cues in the first and third acts indicate clearly where the music is to be inserted.12 Dunlap’s score is actually a good illustration of contemporary incidental music, for – although sometimes referred to as such – The Voice of Nature is not technically a melodrama, since the music neither alternates with nor underlies spoken dialogue.13 The first extant score to a melodrama that is closer to the mark (and the only extant American score for melodrama prior to 1850) is J. N. Barker and John Bray’s The Indian Princess, or, La belle sauvage (1808), which is identified on the title page of the published score as an ‘operatic melo-drame’.14 As a hybrid, The Indian Princess is more than ‘a mixed drama of words and ten bars of music’ (Dunlap’s description of melodrama), for it has both vocal music (songs, glees and choruses) and passages of instrumental melodramatic music that underlie mimed dramatic action.15 Music used to accompany action was borrowed from the world of pantomime; small dances and closed-form songs (usually seen at the beginnings of scenes) were traditions from opéra-comique and ballad opera.16 Most of the melodramas popular on the American stage prior to 1850 were from London (or France via London); most probably had new music composed by American theatre composers, and none survives.17

One final insight into the popularity of early melodramas in America comes from an examination of the careers of French dancers who toured the United States during the period. One such is Madame Celeste Keppler Elliott (b. 1810), a French actress and dancer. Like other French dancers who visited during this period, Madame Celeste originally performed in ‘ballets’ (in her case, in New York after her arrival in 1827), but very quickly switched to melodramas such as The French Spy; or, the Siege of Constantina (with music by Daniel François-Esprit Auber), in part because of the popularity of the form, in part because the lead female role in the melodrama is mute (her spoken English was weak). Madame Celeste eventually used as performance vehicles some dozen mimed melodramatic works (including an adaptation of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Wept of Wish-Ton-Wish); as a ‘melodramatic artist’ she mounted several lucrative tours of America from the late 1820s to the early 1840s.18 Presumably the music to many of the works in which she and other dancers so successfully appeared was composed, as was normal, by musicians associated with American theatres. The performances of such dancers in both ballets and melodramatic works suggests a clear overlap between the two styles of dramatic art; Madame Celeste’s remarkable success on the American stage, furthermore, is additional evidence of the popularity of melodrama.

Itinerant Singers and Vocal Stars

In the 1810s a new kind of musical performer began making the rounds of theatres in the United States; they were the musical counterparts of the theatrical ‘stars’ who had begun to visit in the 1790s. These vocal stars began to arrive individually in 1817; they performed in concert and in operas with stock companies, all of which still included in their standard repertories English operatic works by such composers as Thomas Arne, Charles Dibdin, William Shield and Thomas Linley.19 These early vocal stars were followed in the 1820s by a whole host of (mostly) British singers, who toured on the American theatrical circuit in the company of such British theatrical stars as Edmund Kean, William Charles Macready, Junius Brutus Booth, Peter Richings and Charles Kemble. The most important early vocal stars were Elizabeth Austin (toured 1827–35) and Joseph and Mary Anne Paton Wood (1833–36, second tour in the 1840s), who opened the floodgates for additional singers in the 1830s and early 1840s. Vocal stars who banded together into small ‘vocal-star troupes’ in the late 1830s included Jane Shirreff (1811–83), John Wilson (1801–49) and the husband-and-wife team of Anne (?1809–88) and Edward (Ned) (1809–52) Seguin, all of whom arrived in 1838. These singers toured up and down the East Coast, utilising the expanding steam (rail and water) transportation system to take them to large cities as well as to the smaller towns and hamlets in between. These (and many other) singers – whether touring alone or as duos or trios – became a regular part of American popular musical theatre; they electrified American audiences, who flocked to performances and who purchased reams of arias ‘as sung by’ the vocalists, whose images were engraved on sheet music covers. The singers took the starring roles in standard English comic operas such as those mentioned earlier, with stock company performers singing secondary roles and functioning as the chorus. They also introduced to American audiences more opera from the bel canto and French schools (in English adaptation), including works by Auber, Boieldieu, Rossini, Bellini and Mozart.20 These translated operas fitted readily into an American theatrical repertory that already included English comic and ballad operas, pantomime and melodrama. But the introduction of the more difficult bel canto operas – made possible by the higher-calibre performances of the itinerant vocalists – thrilled American audiences of all economic classes; as a result, Americans developed an almost insatiable appetite for Italian operatic music. The enthusiastic reception of the newer operatic repertory opened the door both for larger English opera troupes (starting in the 1840s) and for foreign-language opera companies. The singing by the women vocal stars, in particular, spurred a fondness among Americans for ‘bird-like’ vocal gymnastics that would continue throughout the century.

In 1825 the Spanish tenor Manuel García (1775–1832) visited New York City with his family (including his daughter María Malibran), where they mounted the first American seasons of opera in Italian.21 Two years later John Davis’s French Opera Company of New Orleans embarked on an East Coast tour, the first of six annual tours (1827–1833) during which they performed opera in French in various East Coast cities.22 Throughout the 1830s numerous itinerant Italian opera companies (mostly based in New York) attempted to capitalise on the growing American taste for this particular flavour of musical theatre; they met with varying degrees of success, but built the foundation for many more – and more successful – Italian opera troupes that would follow in the 1840s.23 It is worth reminding the reader that during this period, both English and foreign-language opera fitted easily into the American theatrical repertory. Opera had not yet been segregated from the regular theatre, nor did Americans readily make a distinction between ‘theatre’ and ‘musical theatre’.

The Nineteenth Century: c. 1840–1865

By the 1840s the infrastructure to support the theatre in America was firmly in place. The increase in population in the country (fuelled, in part, by a phenomenal immigration rate) was such that there were now numerous towns and cities large enough to support at least one – and frequently more than one – theatre with a resident stock company. These theatres now hosted on a regular basis increasing numbers of theatrical and musical ‘stars’, who utilised the ever-expanding steam-powered transportation system.24 The stock companies – with or without the ‘stars’ – performed repertory that continued to be heavily musical in nature. Added to the mix of visiting stars were specialised musical-theatrical performers who likewise traversed the theatrical circuit in ever-increasing numbers: blackface minstrel troupes; English, Italian and French opera companies; acrobats, dancers and pantomimists – each of these will be discussed later. The ‘star’ system would eventually destroy the stock company system (and the fault lines were already readily apparent during the 1850s and 1860s); it would be replaced in the last decades of the century by the combination system, of which these itinerant ‘specialty’ companies already proliferating in the 1840s and 1850s were forerunners. During the period from 1840 to 1865, however, the dominant modus operandi for theatrical production was still the local stock company, augmented by ‘stars’ and supplanted, for weeks at a time, by visiting troupes of minstrels, opera singers or specialty acts.25

The theatrical offerings available to American town or city dwellers in the 1840s and 1850s changed regularly – usually weekly or biweekly – and (by modern standards) varied wildly. To antebellum Americans, going to the theatre was the modern equivalent of going to the multiplex cinema, and the range of diversity represents a certain degree of catholicity of taste among the middle and upper middle classes. By the 1850s there were already apparent seeds of the breakdown in theatrical tastes that eventually would result in a more socially and economically stratified audience; during this period, however – especially in non–East Coast towns that supported fewer theatres – that stratification was not yet a fait accompli. Americans went to the theatre regularly and enjoyed a wide array of different kinds of entertainments, most of which could be considered, by the standards of later centuries, musical.

Stock Company Repertory: Melodrama and Plays with Songs

Melodrama continued its dominance of the American theatrical repertory during this period. By the 1850s, the earlier technique of alternating speech and music had given way to more specialised use of music within the drama: to draw attention to – and heighten the emotional impact of – specific scenes or portions of scenes. As Shapiro points out, instrumental music was now used to heighten ‘strong emotional moments of the play when speech was inadequate or even – as in a fight scene – realistically impossible’.26 It was also during this period that the term ‘melodrama’ came to refer not to a technique but rather to a particular kind of drama (whether or not it included music). This stereotype (of characters, clearly good or evil, involved in an action-filled plot where evil temporarily succeeds but is eventually defeated by good) is the popular definition of melodrama today (Snidely Whiplash and Dudley Do-Right of Rocky and Bullwinkle fame come immediately to mind); its dramatic style clearly provides much opportunity to use music to express emotion.

Few scores have been found for melodramatic pieces from this period, but those that are extant indicate that there were generally some thirty or forty ‘melos’ per drama, and that they were composed (not improvised) for full theatre orchestra. Evidence from prompt books also suggests that the melodramatic music was used in tight coordination with scenic and lighting effects to create the heightened mood. Pantomimic techniques such as short snippets of ‘hurry music’ were employed regularly to underscore quick action or to indicate emotional agitation.27 In its impact on audience members, the music was probably similar to film scores today: extremely successful in terms of underscoring dramatic emotion, but almost completely unnoticed by most auditors.

By mid-century the use of instrumental music for melodramatic effect had become so accepted a theatrical practice that it was not uncommon for such music to be added to non-melodramatic plays. Dramatised versions of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin are instructive. The novel, which became an immediate bestseller after its publication in 1852, was adapted to the stage within the year. Extant programmes, prompt books and playbills suggest clearly that music was central to the performances. One published version includes some two dozen cues for instrumental music to undergird particularly emotional scenes (Eliza’s escape, Simon Legree’s whipping of Uncle Tom or Eva’s assumption).28 Stage productions also included hymns, minstrel tunes and sentimental songs; some were composed specifically for adaptations of the novel, but others were simply popular songs interpolated into particular productions. This insertion of vocal music into stage productions was by no means unusual performance practice for the period and is further evidence of the important role of music in the American theatre at mid-century.

Blackface Minstrelsy

Blackface minstrelsy, the most important American musical-theatrical development of the antebellum period, would quickly come to rival melodrama in popularity. Ostensibly, the form burst upon the American theatrical scene in 1843, with the inaugural appearance of the Virginia Minstrels in New York City. In reality, the four performers who banded together to form the troupe simply codified performance traditions and techniques – including blackface – that had been seen on the American stage for decades; they also incorporated sensibilities, such as burlesque of the powerful, that had been part of Western culture for centuries.29

The Virginia Minstrels’ format quickly became the standard for other early minstrel troupes: four or six performers, all male and all in blackface, would stand on stage facing the audience in a line or a shallow semicircle; ‘Mr Bones’ (who played a rhythmic ‘instrument’ fashioned from animal bones) and ‘Mr Tambo’ (who played a tambourine) would be on either end, with the ‘Interlocutor’ in the middle. The performance was divided into two halves, and included a wide variety of entertainment modes, including singing, skits, jokes, dancing and stand-up comedy; the first half focused on the stereotype of the urban dandy, the second ‘portrayed’ plantation life. The minstrel songs and dances at first were inspired by the emerging fiddle-tune tradition but quickly came to be influenced by other popular-song traditions, including sentimental songs, glees and the four-part harmony of itinerant singing families.30 Minstrelsy, at bottom, was a musical experience; excepting the skits and comedy routines, the entire performance was musical in nature, with song accompaniments and dances alike performed by the minstrel band, which consisted of fiddle, banjo, tambo and bones.

Blackface minstrel troupes quickly joined the other ‘specialty’ musical-theatre companies on the circuit in the 1840s and 1850s, attracting audiences of varied social and economic classes.31 With the increased commercialisation of the form during the late 1840s, minstrel troupes became more streamlined and the format more formulaic. By the late 1850s the first section had become more of a song concert (of genteel and sentimental songs), and a middle section – called the ‘olio’ – had been added; this latter featured blackface songs and burlesque skits, mocking everything from Shakespeare, to singing families, to opera. The third and final part remained the core of the show, with its ‘depictions’ of extended plantation scenes. The whole theatrical extravaganza ended with a finale called a ‘walk-around’, in which the entire company would parade around the stage, singing and accompanied by the minstrel band.32 The increased commercialisation of the form is also evident in minstrels’ exploitation of the growing technology of popular culture. Minstrels – like other contemporary theatrical companies – utilised the expanding American transportation network to travel all over the eastern United States; they published songbooks containing the words of their latest tunes, and sheet music of the sentimental ballads featured in their performances; they corresponded with musical or theatrical journals of national circulation, which published reports of their comings and goings; they advertised upcoming performances in local newspapers prior to arrival in town. Exploitation of such tools helped rapidly to create a large audience for this new musical-theatrical form.

To a great extent the minstrel show – which would continue to evolve and change after the Civil War – was a condensation of various elements of American popular musical theatre during the period. Essentially a variety show (a musical-theatrical form that would become increasingly popular), minstrelsy featured dancing, singing and irreverence; undergirding it all was an emphasis on burlesque, which was an elemental aspect of nineteenth-century American humour.

Pantomime, Ballet, Spectacle and Extravaganza

The pantomime tradition on the American stage had changed significantly by mid-century: the earlier English mode was replaced by a style of visual theatre best exemplified by the family of Gabriel Ravel – exponents of the ‘French style’ of pantomime, and entertainers extraordinaires during the 1840s and 1850s. The four Ravel brothers, who combined physical virtuosity and sophisticated stage machinery with the visual narrative of pantomime (all to musical accompaniment), arrived in America with their entourage in 1832 and toured all over the country (including California) before returning to France in 1858. (Some members of the family returned to the States in the 1860s.33) Nor were the Ravels the only performers in their genre; other troupes – both foreign and domestic – likewise traversed the American theatrical circuit at mid-century and dazzled their audiences with feats of physical prowess. A typical Ravel Family programme consisted of several parts: a pantomime, physical feats (tightrope tricks, balancing, military and sporting skills, and exhibitions of tableaux), and a ballet (e.g. the first act of a contemporary ballet, such as Paul Taglioni’s La sylphide, including a grand pas de deux, a quickstep, a Grand Tableau and ‘The Flight of the Sylphide’).34 The strength of the Ravel Company was its mixture of repertory: ballet, gymnastic skills and (most important) pantomime. The latter category – especially the combination of physical virtuosity, pantomimic narrative and stage machinery and scenery – would evolve into a form that several decades later would be termed ‘spectacle’ or ‘extravaganza’.

American theatregoers during this period also witnessed many itinerant European dancers who were the successors to Madame Celeste. The Austrian ballerina Fanny Elssler (1810–84) was the most prominent visitor of the 1840s; she toured from 1840 to 1842 and provoked an outpouring of near-hysterical adulation from American audiences. Many individual dancers and entire troupes (such as the Rousset sisters, the Montplaisir Ballet Troupe, Natalie Fitzjames, the Ronzoni Ballet Company and others) toured the United States in the 1850s and 1860s; they frequently performed either as part of or in conjunction with opera troupes. Their repertories included divertissements or portions of nineteenth-century ballets such as La sylphide (music by Herman Løvenskiold), Le dieu et la bayadère (Auber) and La sonnambule (Ferdinand Hérold).

Very little research has been conducted on companies like the Ravels or on ballet troupes that toured America in the nineteenth century; as a result, we have almost no knowledge of the music that accompanied these performances.35 Both types of performers (and their music), however, were ubiquitous; as such, they must be included in a discussion of the antecedents of the modern musical. Furthermore, it should be clear that both ‘pantomimic acrobats’ and dancers had an important role in the formation of ‘spectacle’ and ‘extravaganza’, two closely related musical-theatrical forms that would become popular in the second half of the century. Another important proponent of American ‘spectacle’ and ‘extravaganza’ was Laura Keene, whose shows – which combined burlesque, music, ballet, transformation scenes, and spectacular scenery and costumes – were among the most popular theatrical works in New York during the 1860s.36 All of these theatrical forms (burlesque, pantomime, ballet and drama), accompanied by music and augmented by lavish costumes and scenery, commingled and cross-fertilised during the second half of the century; all had a role in the eventual formation of the twentieth-century American musical.37

Burlesque

The American theatrical burlesque in the early and mid-nineteenth century was a dramatic production of a satirical and humorous nature (the form would only later become a variety show with striptease as its major component). By the mid-nineteenth century, the form had adopted some of the characteristics of extravaganzas – in particular, whimsical humour presented in pun-filled verses full of double and triple entendres and oblique humorous wordplay. Burlesques also began during this time to include a significant amount of music.38 Poking fun at someone or something – whether German or Irish immigrants, the pretensions of the wealthy, African Americans or the latest entertainer to catch the public’s fancy – was so much a part of American humour in the nineteenth century that the popularity of a musical-theatrical form of this nature was inevitable. Hundreds of burlesques or burlesque-extravaganzas (mostly one-act farces or afterpieces) were written for the American stage in the 1840s and 1850s; as already mentioned, the technique was also employed by blackface minstrel troupes in the ‘olio’ sections of their performances.

In New York the burlesque was raised to new heights by the actor/manager William Mitchell at his Olympic Theatre starting in the late 1830s; Mitchell’s competitor, the actor and playwright John Brougham (1810–80), followed Mitchell’s successful example and wrote and acted in numerous burlesques from 1842 until 1879.39 The best example of Brougham’s burlesques (and one of the most popular of the century) was Po-ca-hon-tas; or, the Gentle Savage (1855), a parody on Indian plays that were currently the rage. The music, which occupies more than a third of the show, was arranged by New York theatre composer James G. Maeder; it ranges from simple contrafacta (to the tunes of ‘Rosin the Bow’, ‘Widow Machree’ and ‘The King of Cannibal Islands’, all identified in the script) to complicated extended pieces constructed by patching together tunes from sources as widely divergent as ‘Old Folks at Home’ and ‘Là ci darem la mano’ from Don Giovanni. The long-lasting popularity of Po-ca-hon-tas would keep it – and its example as a successful merging of burlesque and music – before the American public for decades.40 From the 1860s onwards, burlesques often functioned as the framework for elaborate spectacles and extravaganzas, the characteristics of which have already been discussed.

Opera: English, French and Italian

By the 1840s, the vocal stars that had been such an important part of the American stage had all but disappeared, replaced by English opera companies performing repertory that had become firmly established as popular theatre. The Seguin Opera Company, a troupe that was both wildly popular and enormously successful, had a virtual monopoly on English opera performance during the 1840s. It – like other English troupes that began to appear later in the decade – performed repertory that included works by British composers (Wallace, Balfe and Rooke) as well as translations of operas by French (Auber and Adam), German (Weber and Mozart) and Italian (Bellini, Donizetti, Mercadante and Rossini) composers. In the 1850s English opera began to be considered old-fashioned, as increasing numbers of large, skilled Italian troupes performed on the American theatre circuit. Despite the competition, several English troupes – including the Pyne and Harrison, the Anna Bishop and the Lyster and Durand English opera companies – managed to mount very successful tours in the United States and maintained a strong presence within the repertory of American popular theatre.

French opera during this period was firmly established in New Orleans, but was represented in the rest of the country primarily by the performance of translations of French repertory (by Auber, in particular), usually by English opera companies. In the 1840s and 1850s a handful of French opera companies – some from New Orleans and some from France – toured America, but the heyday of French opera would arrive only in the 1860s, with the influx of the operettas of Jacques Offenbach and companies to perform this repertory.41

The major thrust for operatic development during the middle decades of the century was in the arena of Italian-language opera. Various incarnations of the Havana Opera Company visited occasionally during the 1840s (performing in New Orleans, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, and on the East Coast), and numerous transient New York–based Italian companies imported from Europe appeared and performed repertories of works by Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti and – increasingly – Verdi. The overall picture of Italian operatic activity in the 1840s and 1850s is one of growth: larger and more polished companies, more extensive itineraries and repertories and more troupes. Furthermore, many of the imported Italian singers remained in America after the completion of their companies’ tours; by the early 1850s there were enough Italian singers living in New York (and teaching music there) to make possible the formation of locally based Italian opera companies. Because of this development, impresarios such as Bernard Ullman, Max Maretzek, Maurice Strakosch and Max Strakosch could circumvent the logistical and financial difficulties inherent in recruiting an entire company from abroad and could now concentrate recruiting efforts (and funds) on big-name stars. As a result, impresarios could engage higher-calibre performers, which contributed to the established trend: heightened audience expectations and subsequent engagement of even more highly skilled musicians. The list of stellar singers who appeared in various companies in the United States during the period includes some of the best vocalists of Europe: Marietta Alboni, Henriette Sontag, Teresa Parodi, Giovanni Matteo Mario, Giulia Grisi, Lorenzo Salvi and many others. It is important to reiterate that although Italian-language opera was beginning, by the 1850s, to become associated with the elite and wealthy, this change in the opera audience was still new and limited primarily to the East Coast. The appearance of an Italian opera company during the 1850s in a theatre in, say, St Louis or Cincinnati was regarded as a special event (similar to the visit of a major dramatic star); it was not yet regarded as an ‘exclusive’ engagement that appealed only to the elite or wealthy. Italian opera was still entertainment; as such, it was still a part of the constantly changing potpourri of American popular musical theatre at mid-century. Furthermore, music from the operatic stage, by this time, had completely infiltrated the American soundscape, and many Americans attended operatic performances to hear music that was readily familiar. Americans danced to quadrilles and lanciers fashioned from tunes from the most popular continental operas; they heard brass bands playing these same tunes in open-air concerts; theatre orchestras performed operatic selections as entr’acte music or overtures; piano benches all over America overflowed with piano variations, arrangements of operatic ‘gems’ and sheet-music adaptations of the most popular arias. Musical theatre, then, was not limited to theatres; it permeated American life.

The Nineteenth Century: c. 1865–1900

The last third of the nineteenth century was a period during which musical-theatrical forms on the American stage proliferated to the point of rank confusion. Most of the styles already discussed (burlesque, minstrelsy, opera, melodrama, pantomime, dance and plays with songs) continued to be performance vehicles, but these older styles mutated, expanded and cross-fertilised each other. Furthermore, new styles were introduced: operetta (including opéra-bouffe, Austrian and British operetta and ‘light operas’ by American composers), farce-comedy, spectacle/extravaganza and the expansions of variety (including the early revue and the shows of Harrigan and Hart).

By this time many of the local stock companies of earlier decades had disappeared; most theatres now relied exclusively on the itinerant ‘combination’ companies that performed everything from drama and opera/operetta to variety and farce-comedy. Itinerant musical-theatrical companies now toured all over the United States, including – after the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 – the interior of the far West. Although many of the theatrical innovations of this period can be covered by an examination of developments in New York City, this should not mislead the reader; travelling performers were able to exploit fully a well-developed transportation system that criss-crossed the United States, and they took their performances to city and hamlet alike. During this period there also emerged the theatrical syndicate – a central managerial office (usually in New York, Boston or Chicago) that controlled both local theatres and the itinerant troupes that visited them.42 This centralisation of control exemplifies another element of the coming-of-age of the theatrical business. Scheduling was much less haphazard; managers also exploited the national and local press for purposes of advertising and publicity and collaborated with publishing houses to ensure that ‘hit’ songs from popular shows would be readily available to consumers in sheet-music format.

Added to the rank confusion of musical-theatrical forms of the time was an imprecision of terminology that can drive a codifier mad: the same show might be called a ‘farce-comedy’, a ‘revue’ or an ‘extravaganza’; many shows exhibited characteristics of numerous categories. The first use of the term ‘musical comedy’ dates from this period, but there is general disagreement about which show, precisely, the name was first bestowed upon; some of the candidates include The Pet of the Petticoats (1866), Evangeline (1874) and A Gaiety Girl (1894).43 The American musical stage was beginning to come of age during this thirty-year period: metaphorically, it was a gangly and untidy adolescent experiencing a magnificent growth spurt; this diverse yet contradictory youngster would eventually mature into the twentieth-century American musical.

Spectacles, Extravaganzas and Burlesques

During the post–Civil War period terms such as ‘extravaganza’, ‘burlesque’ and ‘spectacle’ were frequently used interchangeably or in combination. The theatrical works in this style were clearly based on forms that had been familiar to American theatregoers for some years, but shows of this nature became more prominent and numerous during the last third of the century.

The Black Crook (1866), with music by Thomas Baker, is frequently cited as the first real precursor to the twentieth-century musical. A combination of many of the forms already discussed, the five-and-a-half-hour extravaganza (performed at Niblo’s Gardens in New York City) included elements of melodrama and fantasy (inspired in part by Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Der Freischütz and Goethe’s Faust), ballet (performed by a troupe of 100 French female dancers, in tights), spectacular scenery and costumes and transformation scenes made possible by sophisticated stage machinery.44 The play, although not particularly novel (it was constructed of many elements already familiar to American theatregoers), became astonishingly popular, achieving a run of 474 performances over the course of sixteen months. It remained a mainstay of the American theatre until almost the end of the nineteenth century. In addition to the music written by Baker for the original production, there were many additional compositions written for interpolation later.45

The success of The Black Crook (coupled with the popularity of the Ravels’ and Laura Keene’s productions) inevitably resulted in a spate of additional extravaganzas and spectacles, including the unsuccessful sequel to The Black Crook, The White Fawn (1868). The two decades after the Civil War marked the height of popularity for American spectacle, which – as we have seen – combined elements from a variety of familiar theatrical forms and in which music played an important role as unifying accompaniment.46 The burlesque-spectacles mounted by Lydia Thompson and her ‘British blondes’, who arrived from London in 1868, are good examples of this admixture of elements. Thompson first appeared in New York in a full-length burlesque, Ixion, or the Man at the Wheel, which boasted of a pun-heavy script, topical references to and burlesques upon contemporary events and people, opéra-bouffe–like songs, spectacle, transformation scenes, gags and dances.47 Thompson and her troupe, furthermore, were responsible for injecting into burlesque the element of the ‘girlie show’ that eventually would become closely associated with the genre. This overt exploitation of stage women as the object of the male gaze represents an important development in the role of women performers on the musical stage; it would have major repercussions early in the twentieth century, in particular with the revue style developed by Florenz Ziegfeld.

Edward Everett Rice’s Evangeline; or the Belle of Acadie (1874), to words by John Cheever Goodwin, is another excellent example of the cross-fertilisation typical of late-century musical-theatrical forms: from spectacle it took elaborate costumes, sets and stage machinery (a spouting whale, a balloon trip to Arizona); from burlesque it borrowed a rhyming text full of puns and topical references, and ostensibly with a literary basis (it was originally a burlesque on Longfellow’s poem, although Goodwin’s version has little to do with its plot); from variety show and minstrelsy it took skits, gags and specialised ‘acts’; from comic opera it borrowed spoken dialogue, a romantic plot, and a musical score of songs, dances, ensemble numbers and choruses.48 There were also elements of melodrama and pantomime in the work, which was the only nineteenth-century musical production to rival the popularity of The Black Crook; it was mounted all over the country for the next thirty years.49

Three years after the premiere of Evangeline, there emerged another style of burlesque, called farce-comedy. The Brook (1877), created by Nate Salsbury and first performed by his troupe in St Louis, was a parody of musical-theatrical conventions, although it was not a burlesque in the standard definition of the form (Salsbury called it a ‘laughable and musical extravaganza’).50 The Brook featured music that was borrowed and arranged; it was also a simple show with a small cast: it was neither an extravaganza nor a spectacle, and it required no chorus, ballet dancers, pantomime, transformation scenes, extravagant costumes or spectacular scenery. From the variety stage and the British music hall, The Brook incorporated the concept that a theatrical work could be casual and natural. The simplicity (and success) of The Brook guaranteed immediate imitations; farce-comedies remained popular in New York for only five years, but itinerant companies (called ‘combinations’) toured North America for the rest of the century.51 The most popular successor to The Brook was A Trip to Chinatown by Charles H. Hoyt (music by Percy Gaunt); this show opened in 1890 and ran for a record 650 performances in its first engagement. Loosely constructed with an extremely thin plot (typical of a farce-comedy) and incorporating elements from vaudeville (such as specialty act appearances by artists such as dancer Loie Fuller), the work featured a score that included some popular tunes that are still known today, e.g. ‘The Bowery’ and ‘Reuben and Cynthia’.

Melodrama

By the last third of the century, the technique of using instrumental ‘melos’ as dramatic cues had become almost ubiquitous in musical-theatrical (and many dramatic) forms of all kinds. Melodrama itself also continued its domination of the American stage; the popularity of full-length melodramatic plays would not begin to wane until the twentieth century.52 Continued popularity in the late nineteenth century was enhanced by the use of more elaborate scenery, better lighting and more sophisticated stage machinery to increase the sense of realism; the overlap with spectacle and extravaganza should be obvious.53 The continued importance of music to melodramatic presentation – and hence the significance of melodrama as one of the precursors of the twentieth-century American musical – is sometimes ignored. As the theatre historian David Mayer points out, however, ‘nowhere is the use of musical accompaniment more pervasive … from ten years before the start of the nineteenth century until well after the First World War, than in the melodrama’.54

Scores to melodramatic works are rare, even from the second half of the nineteenth century; there are perhaps a dozen known scores to such plays in the United States and some thirty in collections in Great Britain.55 One of the most important examples of melodramatic music from this period is for the play Monte Cristo (1883), an adaptation by Charles Fechter of Alexandre Dumas’s 1844 romance novel Le Comte de Monte-Cristo, first produced in the United States in 1870. The twenty-eight melos in the manuscript score, for the most part, are extremely brief, but this music was greatly augmented by overtures and entr’acte music, played before and between the acts. Some of the melos in Monte Cristo are used almost as leitmotifs, not only to indicate entrances and exits of important characters, but also to signify emotional and psychological developments in the dramatis personae. Other non-melo music used in melodramatic plays, however, did not differ significantly from interpolated songs and incidental music performed in many ‘straight’ dramatic plays of the period, indicating both the continued importance of music to most theatrical works and the ubiquitous overlap among different ‘distinct’ forms on the American stage in the late nineteenth century. The subsequent impact of these well-developed (and familiar) melodramatic musical techniques at the turn of the century was twofold. On the one hand, the pervasive use of music for dramatic purposes clearly influenced those individuals who – consciously or unconsciously – were writing the works that would be the immediate precursors to the early musical. On the other hand, melodramatic music would inevitably influence the adaptation of similar melos for use in the early ‘silent’ cinema; the primary difference, of course, was that the musical accompaniment for film had to be continuous instead of intermittent.56

Minstrelsy; Black Musical Theatre

By the final decades of the century the ‘Golden Era’ of blackface minstrelsy (1840s–1870s) had almost run its course. During the 1870s minstrel troupes grew ever larger, sometimes including as many as thirty performers. Known as ‘mastodon’ or ‘giant’ minstrel troupes, these companies grew in order to compete with the burgeoning forms and styles of entertainment emerging during the period.57 Minstrel troupes also began to employ other ‘hooks’: all-female minstrel troupes, all-black minstrel troupes. The first important example of the latter, called the Georgia Minstrels, appeared in 1865; this company (managed by a white man) was followed, in turn, by numerous other troupes, some of them managed by African Americans.58

The advent of black minstrel companies marked the beginning (in the final decades of the nineteenth century) of a great influx of African American performers onto the American stage. Minstrelsy, minstrelsy-influenced vaudeville (or variety) and the craze for ‘coon’ songs all offered to African Americans an entrée into a hitherto all-white world; Allen Woll, in fact, notes that a majority of African American actors enumerated in the 1890 census identified themselves as minstrels.59 The Hyers Sisters represent the first attempt by blacks to produce dramatic shows with songs. The sisters’ combination company produced musical plays starting in the late 1870s and lasting well into the 1880s.60 The influx of African Americans into the theatrical world led, inevitably, to the creation of black ‘musicals’. The Creole Burlesque Co. (1890), produced for the burlesque stage, was very much a minstrel-flavoured entertainment. It was followed by Octoroons (1895), which included a hit Tin Pan Alley ‘coon’ song, ‘No Coon Can Come Too Black for Me’.61 Two shows of 1898 were closer to what we think of as ‘musical comedy’: Clorindy, or the Origin of the Cakewalk (Will Marion Cook) and A Trip to Coontown (Bob Cole) were both vaudeville-like – rather than book-like – musical-theatrical works; the latter was the first musical written, directed and performed by black performers.62

Opera and Operetta

During the last thirty years of the century, the performance of foreign-language opera gradually became a niche market. Although immigrant communities patronised performances in Italian or German, many middle- and professional-class Americans (who had supported foreign-language opera during the antebellum period) increasingly regarded it after the war as an expensive, exclusive and elite activity. By the mid-1870s, in fact, wealthy Americans had finally managed to transform it into that type of endeavour, in part because the economic elite became a large enough demographic to support opera without the assistance of the middle classes, and in part because many non-wealthy Americans grew increasingly antagonistic towards the East Coast wealthy class (and everything associated with it), especially after the Panic of 1873. Foreign-language troupes (including the Metropolitan) continued to tour, but they attracted an ever-smaller slice of the American public even though this type of opera remained a component of the American musical stage. Companies that performed in German or Italian, for example, routinely sang in theatres that also hosted operetta, drama, comic opera and other entertainments, even if they had been built specifically for opera (e.g. Crosby’s Opera House in Chicago; the Academy of Music in Philadelphia; and Albaugh’s Opera House in Washington, D.C.); the exception was the Metropolitan Opera House (1883). The market for foreign-language opera changed only in the late 1880s and 1890s with the emergence of a Wagner craze instigated by the charismatic Anton Seidl.

In contrast, English-language opera became extraordinarily successful during the 1880s and 1890s; its popularity would eventually have an impact on the development of the twentieth-century musical. These companies performed translations of the same works mounted by the foreign-language troupes, but sung in English and without the trappings of elitism and exclusivity. Such troupes toured America regularly in the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s, many of them managed by prima donnas such as Caroline Richings (daughter of the British actor Peter Richings mentioned earlier; active 1863–84), Euphrosyne Parepa-Rosa (active in the US 1865–74), Clara Louise Kellogg (active in English opera 1873–77), and Emma Abbott (active 1879–91), who became the most successful prima donna in America during the 1880s. These companies performed what they called English grand operas (translations of the continental repertory), works written in English and some operettas and comic operas; several troupes billed their productions as ‘opera for the people’, clearly as an attempt to counter the growing perception of opera as an elite pastime. Abbott, known as ‘the people’s prima donna’, reintroduced this style of musical theatre to many Americans; her company, which regularly provided opera-as-entertainment, opened some thirty-five different opera houses in the far West. Her sudden death (of pneumonia) while on tour in Utah provoked a national outpouring of grief from her supporters. Emma Juch, a successful performer with Italian troupes, was also known as a crusader for English opera for ‘regular’ Americans. Dozens of other English-language troupes were active in the United States during this period; they performed a mixed repertory of operas and operettas by composers who wrote in English (Balfe, Wallace, Benedict, Eichberg and Sullivan), French (Auber, Meyerbeer, Lecocq, Thomas, Offenbach, Gounod, Planquette and Bizet), Italian (Mozart, Bellini, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini and – later – Mascagni and Leoncavallo) and German (Mozart, Weber, Beethoven and Wagner).63 The spectacularly unsuccessful American Opera Company, established by Jeanette Thurber in 1885 in an attempt to establish English opera in America, should be noted, but its failure was anything but typical.

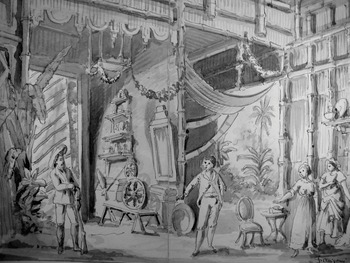

Plate 2 Scenic design for Act 2 from Emma Abbott’s production of the opera Paul and Virginia by Victor Massé (1872) showing the interior of the plantation home of Mons. St. Crois on ‘a picturesque island off the coast of Africa’. Tams Witmark Wisconsin Collection, Mills Music Library, University of Wisconsin–Madison

Many of the English-language companies were increasingly influenced by the growing American enthusiasm for operetta, and many operetta troupes also performed standard repertory. The Boston Ideals, for example – founded in 1879 to perform Gilbert and Sullivan operettas – regularly performed such typical fare as The Bohemian Girl (Balfe), The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart), Fra Diavolo (Auber), Martha (Flotow) and L’Elisir d’amore (Donizetti), in addition to ‘lighter’ operettas such as The Pirates of Penzance and Fatinitza.64 Operetta had first been introduced to American audiences in the 1860s, in the form of the opéras-bouffes of Jacques Offenbach. La Grande Duchesse de Gerolstein was first performed in New York (in French) in 1867. Several troupes mounted this and other works in New York and elsewhere, with great success. The 1870s, in fact, were a heyday of opéra-bouffe production in the United States; performances of operettas by Offenbach, Lecocq, Audran, Hervé and Planquette – in English, French and German – were widespread.65 As a result of the new-found craze for French opera, the number of French companies that toured widely in the United States increased during this time; these included the French Opera Company of New Orleans and troupes formed in support of the opéra-bouffe sopranos Marie Aimée and Lucille Tostée. Offenbach himself visited the United States in 1876 and conducted performances in Philadelphia and New York. As this repertory became more popular, an increasing number of troupes performed the opéra-bouffe repertory in English translation; this, paradoxically, led to a decrease in the popularity of these works, as more Americans understood and were offended by the double entendres and compromised sexual situations of the plots. German companies (notably in New York, Cincinnati, Chicago and Milwaukee) also performed translations of this repertory, but primarily for the large German immigrant populations of those cities.66 The French light opera repertory was augmented during the 1870s and 1880s by Viennese operettas, including works by Franz von Suppé (Fatinitza), Karl Millöcker (The Black Hussar and The Beggar Student) and Johann Strauss (The Merry War and The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief).

The most successful operettas on the American stage during the last third of the nineteenth century were by W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900). Scholars generally agree that the 1878 Boston premiere of HMS Pinafore marks a turning point in the history of American musical theatre.67 Within a year the work had become the most frequently performed operetta in America, with more than ninety Pinafore companies touring the United States. In 1879 Gilbert, Sullivan and the company of Rupert d’Oyly Carte travelled to the United States to perform Pinafore and to mount the world premiere of The Pirates of Penzance (in order to secure the American copyright). Neither Pirates nor The Mikado (1885) achieved the popularity of Pinafore, but the level of performance of the D’Oyly Carte company greatly influenced American operetta and English opera companies, and the format of the Gilbert and Sullivan shows – the inoffensiveness of the humour (especially in comparison with burlesque, vaudeville or even opéra-bouffe), the witty satire at the expense of the British establishment and Sullivan’s skilful melodies – appealed mightily to American audiences. The shows would remain popular for the rest of the century. British operetta clearly had a profound impact on the future course of American musical comedy; Gerald Bordman, in fact, claims that Pinafore itself ‘determined the course and shape of the popular lyric stage in England and America for the final quarter of the nineteenth century’.68 Part of the astonishing success of Pinafore can be attributed to the operetta’s unprecedented assimilation into American mass popular culture; a veritable mushroom crop of amateur theatrical companies – devoted to the performance of Pinafore – sprang up all over America in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

American composers also found a voice in operetta, although most operetta and English opera companies preferred to perform European imports. Julius Eichberg’s Doctor of Alcantara, which was premiered in Boston in 1862, was an attempt by that German immigrant to emulate the success of Offenbach. The show, which was referred to in the contemporary press as an ‘opera’, ‘operetta’, ‘opera of the comic order’, ‘comic operetta’, ‘opera bouffa’ and ‘light operatic entertainment’, entered the repertories of numerous troupes in the 1860s and 1870s and made Eichberg the most successful American operetta composer during the 1860s.69 Other Americans followed in Eichberg’s footsteps, including the opera impresario Maretzek (Sleepy Hollow, or the Headless Horseman, 1879) and J. S. Crossey (The First Life Guards at Brighton, 1879). Willard Spencer’s The Little Tycoon (1886) was almost the only American comic opera to enjoy any popular success in the 1880s. John Philip Sousa, who wrote some fifteen operettas, was clearly influenced by the works of Gilbert and Sullivan, but suffered from inadequate librettos. Although his works held their own against foreign operettas in the late 1880s and early 1890s, his only true success was El Capitan (1896).70 Ludwig Engländer (1853–1914) also enjoyed some success as a composer of comic operas, primarily in the 1890s. George Whitfield Chadwick, a more ‘classical’ composer, also tried his hand at the genre, with Tabasco (1894). Two late-century American composers of comic opera enjoyed greater success than the others. Reginald de Koven (1859–1920) wrote several operettas in the late 1880s, including The Begum (1887), described as a cross between La Grande Duchesse and The Mikado.71 De Koven relied heavily on Gilbert and Sullivan for his only major success, Robin Hood, premiered by the Bostonians (formerly the Boston Ideals) in 1890. Victor Herbert (1859–1924), who also wrote for the Bostonians (and for other English opera companies), was by far the most successful and skilled American comic opera composer of the late nineteenth century. Most of his best-known works – characterised by dramatic and memorable melodies and skilful orchestrations – are twentieth-century works; several of his operettas, however, were premiered in the 1890s, including The Wizard of the Nile (1895), The Serenade (1897) and The Fortune Teller (1898).

Vaudeville and Variety Show

Variety shows came of age on the American stage during the final years of the nineteenth century. Many concert saloons had begun offering ‘light’ varied entertainment in the 1850s as inducement to drink; the amusement was similar to that of the English music hall and included a bill of songs (comic and sentimental), instrumental solos, comic skits, dancing, juggling and acrobatics of various sorts. Americans, of course, were already readily familiar with the format through minstrelsy. By the mid-1860s concert saloons and their style of entertainment were common all over the country; after the Civil War the format moved from saloons into theatres.72 Variety theatres became commonplace during the 1880s and 1890s; as such they – like opera houses – are another example of the increasing numbers of theatres catering to specific audiences. For the most part variety entertainment was considered disreputable (because of the association with saloons and the prevalence of objectionable material). Managers of variety theatres or théátres comiques (including, most notably, Tony Pastor and B. F. Keith in New York) attempted to attract family audiences by cleaning up the content of their shows, professionalising the performances, banning drink and changing the name of the entertainment form to ‘vaudeville’, a term already used in Europe for variety-like entertainment.73 Playbills from American variety theatres from the last two decades of the century illustrate the diversity of programming: an evening’s entertainment might consist of a full-length vaudeville show, burlesque skits, revues, magic shows and minstrelsy; most of these performances were to musical accompaniment.74 It is also during this period that many variety entertainers began fruitful collaborations with music publishers to ‘plug’ particular songs. This combination of musical theatre and music publishing illustrates another aspect of an emerging music business that occurred during the early Tin Pan Alley era; it also suggests the important role of musical theatre in that coming-of-age.

In the 1870s many variety shows – like minstrel shows – included extended comic skits. One variety performer who eventually transformed his skits into something much closer to an extended musical-theatrical show was the actor, lyricist and playwright Edward Harrigan (1844–1911), who in 1871 teamed up with the actor Tony Hart (Anthony Cannon, 1855–91) to form the variety team of Harrigan and Hart. In the same year Harrigan also commenced a fruitful collaboration with the established theatre composer Dave Braham (1834–1905); the partnership eventually produced a whole series of comical musical plays that relied heavily on burlesque and ethnic humour (caricaturing Irish and German immigrants as well as African Americans). The first version of The Mulligan Guard, from 1873, was a ten-minute sketch typical of variety-show fare: it contained three or four songs, dialogue, and ‘gags and business’.75 Encouraged, Harrigan and Braham continued to expand upon the theme; eventually the sketch evolved into a full-length play that, in turn, spawned an entire cycle of related ‘Mulligan’ musical plays that were performed (in New York and elsewhere) throughout the 1880s and into the 1890s.76 The evolution of the Mulligan series is a perfect example of the transformations and cross-fertilisations characteristic of the American stage: a variety show song-and-dance routine developed into a full-length musical entertainment that incorporated elements of variety, burlesque, melodrama and minstrelsy. Furthermore, the growing importance of Dave Braham’s music – the increased number of songs and the greater reliance on incidental music as dramatic cues (in the style of melodrama) – points clearly towards the close integration of music and drama that is the hallmark of the mature American musical comedy.77

In the 1890s variety continued to be popular on the American stage; many other individuals important to the development of American musical theatre cut their performance teeth in vaudeville. One of the most notable was George M. Cohan (1878–1942), whose play Little Johnny Jones (1904) is frequently cited as the first American musical. Cohan grew up a member of his family’s itinerant vaudeville troupe (‘The Four Cohans’). The company’s first musical comedy, The Governor’s Son (1901) – like Ned Harrigan’s works of twenty years earlier – was an elaboration of a vaudeville sketch. This show was an immediate failure, but the dramatic and musical seeds were sown and would result, three years later, in Cohan’s more integrated Little Johnny Jones.

Another style of entertainment that would have an impact on twentieth-century musical theatre also emerged in the 1890s on the vaudeville stage. ‘Revues’, a style of entertainment that had become popular in Paris, were introduced in New York in the early 1890s. The first successful American example of this genre, The Passing Show (1894, Ludwig Engländer), was called a ‘topical extravaganza’ and combined burlesque, satire, specialty acts, minstrelsy, dance, a scantily clad female chorus and tableaux vivants; in essence it was a variety show in the best of the American tradition.78 The revue as a form would have a profound impact on musical theatre of the early twentieth century; the ‘follies’ and ‘scandals’ of Florenz Ziegfeld and George White (for which composers such as Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and Cole Porter wrote music) were outgrowths of this Parisian style.

Conclusion

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the theatrical realm was not so clearly separated from normal life as it is now; elements of the stage permeated American life during this period – especially the last several decades of the nineteenth century – to an extent almost unimaginable today. Americans were readily conversant with songs from theatrical venues as widely divergent as opera and variety show; their dance cards were full of music from the stage; they played arrangements of show tunes on their parlour pianos, mounted amateur productions of operettas and listened to concerts by the local brass band playing arrangements of music of operas, operettas and variety shows. Furthermore many Americans of varied social and economic standing attended musical-theatrical performances with a matter-of-fact regularity foreign to us today. The variety of musical-theatrical repertory available then is approximated two centuries later only in the largest of American cities, or in the local multiplex.

It is also impossible, for most of the nineteenth century, to view the repertory of ‘musical theatre’ as different and distinct from the repertory of the ‘theatre’. It is true that by the final decades of the century the concept of the ‘legitimate’ stage – a style of drama that did not include music – had begun to emerge. But as the theatre historian David Mayer points out, this development – which modern theatregoers take for granted as the natural order of things – was an aberration and clearly marked a change from long-standing tradition.79 A thorough understanding of the antecedents of the American musical, then, must include an examination of a wide variety of different types of musical-theatrical styles and genres, including many that today are not included in the modern definition of ‘musical theatre’.

Finally, it is important to realise that our modern preference for clear distinctions between musical-theatrical forms even in the twentieth century is sometimes artificial and counterproductive. Well into the twentieth century American ‘musical theatre’ continued to be varied and changeable, with a rich and valuable tradition of cross-fertilisation; as Joel Kaplan notes in his introduction to a study of the Edwardian theatre, it is precisely this ‘interplay of forms or genres that seems, to late twentieth-century eyes, one of the most remarkable features of pre-[World War I] entertainment’.80 It is clear that during at least the first third of the twentieth century, composers and performers moved readily between variety, film musicals, burlesque, revues and book musicals. Recognition of this is essential in any attempt to understand the development of the American musical; it also illustrates a healthy continuation – into the twentieth century – of many of the musical-theatrical traditions of the nineteenth.