The world of festivities and music has always opened a wide range of possibilities for understanding the Afro-descendant and slave experience in the Americas.Footnote 1 Slave songs – understood here as songs, dances, movements, and genres developed by the enslaved – were, in Shane and Graham White’s felicitous expression, powerful “songs of captivity.” “Slave culture,” they write, “was made to be heard.”Footnote 2

Slave songs profoundly marked the history of conflict and cultural dialogues in slave and post-slavery societies across the Americas. They were part of the repressive disciplinary policies of slaveowners, police, and religious authorities, yet they also proved critical to enslaved people’s strategies of resistance, negotiation, and political action. The right to celebrate according to their own customs was – alongside demands for manumission, access to land, and family organization – one of the most important demands of the enslaved in their struggle for autonomy and liberty. The “sounds of captivity” – whether inherited directly from Africa or learned and recreated in the New World – were a constant in the senzalas (slave quarters), workplaces, plantations, cities, meeting places, and religious events of the United States, Brazil, and the Caribbean.Footnote 3

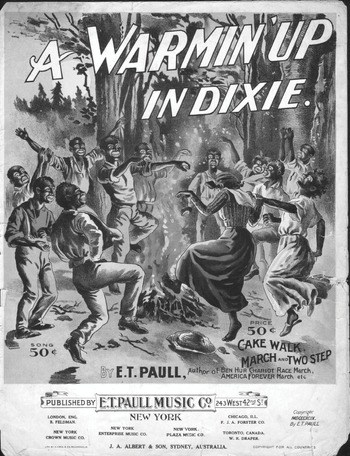

But slave songs also had an impact far beyond the world of enslaved people and their celebrations. Slave songs became spectacles in social and religious events organized by slaveowners, who sought to impress visitors and demonstrate their dominion over slaves. In a depreciative and racist manner – often hovering between the grotesque, the ridiculous, and the sentimental – slave songs appeared in the blackface spectacles of minstrel shows in the United States and Cuba and were also performed by white artists and clowns in Brazilian revues and circuses during the second half of the nineteenth century. Slave songs – written here in italics to differentiate them from the songs sung by slaves during captivity – frequently took the form of coon songs, Ethiopian melodies, cakewalks, lundus, jongos, and batuques. These songs, though not necessarily their Black protagonists, enjoyed great success in the promising sheet-music market (see Figures 15.1 and 15.2), as well as in ballrooms, circuses, and theaters. They triggered memories of captivity and of Africa as well as racist images of Black people and cultures. As genres, they competed with waltzes, polkas, havaneras, modinhas, and recitatives and would eventually enjoy success in the phonographic industry.

Figure 15.1 Sheet music. E.T. Paull, “A Warmin’ Up in Dixie,” 1899. Historic American Sheet Music, Duke University. https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/hasm_b0158/.

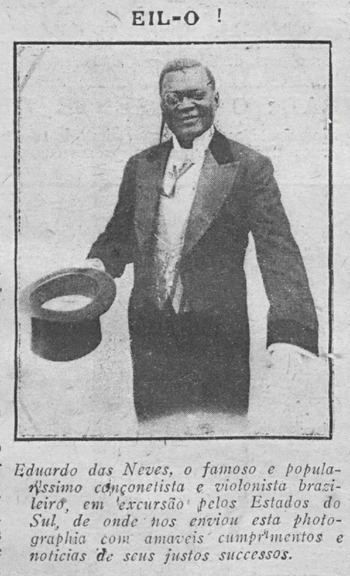

This chapter investigates belle époque slave song performance on the stage and in modern cultural circuits throughout Brazil and the United States, exploring its many dimensions and tensions. Focusing on two Black musicians, Eduardo das Neves (1874–1919) and Bert Williams (1874–1922), this chapter will examine these tensions in depth, revealing in the process the Black diaspora’s musical connections and links across the Americas and especially south of the equator.

Eduardo Sebastião das Neves was the first Black singer to make records in Brazil’s emergent phonographic industry during the first decade of the twentieth century. In previous works I had the opportunity to demonstrate how Neves linked his musical production to crucial political questions such as the valorization of Brazil’s republican heroes or Rio de Janeiro’s urban problems. His music, published in widely circulating songbooks and recorded in the nascent phonographic industry, represented a noteworthy form of politics. At the same time, Neves’ compositions also represented a musical connection to the slave past and the experience of Brazil’s post-abolition period, a fact that may have augmented his success. For his repertoire, Neves chose themes involving slavery, the conquest of freedom, the construction of Black identity, and the valorization of crioulos (Brazilian-born Afro-descendants) and mulatas. Eduardo das Neves proudly called himself “the crioulo Dudu” and was proud of his talent as a singer of lundus, a comical song genre heavily associated with Brazil’s Black population.

However, as my research advanced, I realized that an approach limited by national boundaries was increasingly insufficient. Eduardo das Neves was employed by an incipient phonographic industry that was based on multinational capital and had strong roots in and connections with the United States.Footnote 4 With that expanded perspective, I came to understand Neves’ production as part of the musical field of slave songs, which had established itself as a privileged space of entertainment and business in various cities in the Americas between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth.Footnote 5 I thus soon came to suspect – and suggest – that Eduardo das Neves was not alone. His trajectory paralleled that of many Black musicians from other parts of the Americas. His repertoire and performance style, in turn, echoed a larger set of representations of Blacks and what was understood as “Black music” in the commercial circuits of musical theater and the phonographic industry across the Atlantic World. The circulation of recorded music – that era’s most modern cultural product – catalyzed the diffusion of musical genres identified with the Black population.Footnote 6

This chapter aims to deepen our understanding of this history, valorizing the agency of Black musicians in constructing what Paul Gilroy has already celebrated as the “Black Atlantic,” in this case south of the equator at the beginning of the twentieth century. Brazil’s musical historiography does not usually highlight Black musicians’ protagonism in the transformation of the musical field, much less their participation in international cultural circuits before the 1920s. Until very recently, Brazilian histories of music generally argued that Brazilian popular music was above all the space where a disparate nation united; that it constituted the cultural fruit of the intermixing of Portuguese and Black peoples. In interpreting Brazil’s twentieth-century musical production, Brazilians have widely employed maxims from the myth of racial democracy.Footnote 7

Atlantic Conflicts and Connections in the Post-Abolition Period: Black Musicians as Protagonists

Abolition was a political landmark in the nineteenth-century Americas, but it did not substantially alter the paths already followed by slave songs in Brazil and the United States. Slave songs did, however, substantially expand their reach during that time, due to the acceleration of commercial and cultural exchanges in the Atlantic – both north/south and east/west – and the emergence of the phonographic industry.Footnote 8 At the turn of the twentieth century, a transnational commercial entertainment network involving circuses, vaudeville, and variety shows stimulated the widespread circulation of styles and people between Europe and the Americas. One result was a magnetic new form of dance music based on genres and rhythms identified with America’s Black populations.

Complementarily, slavery’s end introduced new elements to the discussion of slave songs’ meanings and significance; across the Americas, emancipation opened possibilities for Afro-descendant participation in newly free nations and the extension of the freed population’s civil and political rights.Footnote 9 Even in the United States, where outsiders had begun to recognize the immense value of spirituals after they were “discovered” by northern progressive folklorists at the end of the Civil War,Footnote 10 debates about Afro-descendant musical contributions to national culture and identity became important to the agendas of musicians, intellectuals, and folklorists.Footnote 11

Slave songs did not disappear with abolition, as some hoped and believed would happen. On the contrary, and not by chance, slave songs – renewed in diverse genres such as cakewalk, ragtime, blues and jazz in the United State, rumba and son in Cuba, calypso in the English Caribbean, and lundu, tango, maxixe, and samba in Brazil – invaded the modern Atlantic circuits of Europe and the Americas in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 12 They attracted the attention of erudite musicians and European modernists,Footnote 13 as well as that of cosmopolitan businessmen and urban populations across the globe that thirsted for cultural novelties.

However, even as Afro-descendant music and dance achieved success on the world stage, free Afro-descendants’ access to venues for artistic expression, citizenship, and society itself were increasingly limited by beliefs about nonwhite inferiority that also circulated throughout the Atlantic world. Scientific racism, which posited the inferiority and degeneration of Africans, would eventually inundate the musical world.

In nineteenth-century Europe and the Americas, Black bodies and their movements came to be interpreted on the basis of racist theories of sex, gender, and culture; resignifications of Africa in the modern artistic field would further reinforce the inequalities of racial representations.Footnote 14 Newly valorized representations of slave and Afro-descendant music and dance could still naturalize, rank, and ridicule cultural, musical, and racial identities and differences. Characterizations of Black people and their musical genres – projected in theaters, through song lyrics, on the covers of sheet music, in concerts, on stages, and in musical recordings – helped create and disseminate post-abolition allegories about Afro-descendant inferiority and racial inequality.

The success of slave songs during the decades spanning the turn of the twentieth century cannot be seen in isolation, nor as simply the fruit of French and European modernities, as the Brazilian historiography has often suggested. Nor can the slave songs be considered a “natural” or transparently “national” expression, as many folklorists once argued.Footnote 15 The slave songs’ popularity certainly did not indicate the existence of a flexible space that facilitated slave descendants’ visibility and social mobility. Their success instead needs to be researched through the deeds of the social actors who invested in the struggle for citizenship and visibility in the post-abolition world. The commercial ascension of rhythms, themes, and genres identified in some way with the Black population opened space for Afro-descendants who struggled for liberty and autonomy in order to construct new trajectories or fought successfully for inclusion in the modernity of nations that were not willing to fully accept them.Footnote 16

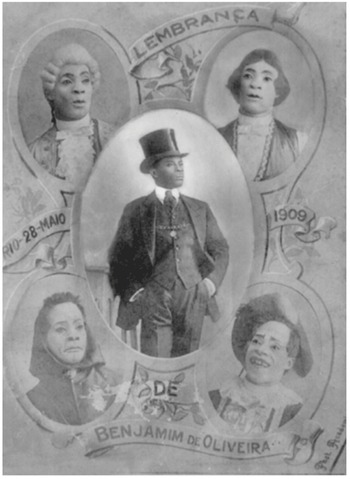

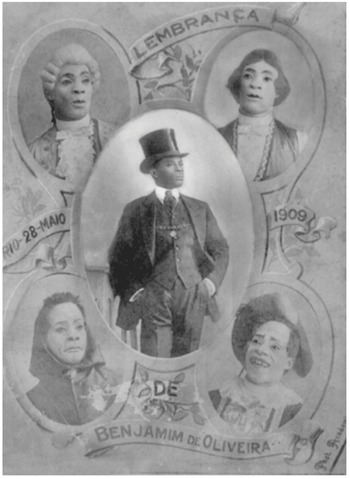

Although the slave songs’ Black protagonists did not necessarily accompany the new and modern musical genres as they traveled through global commercial circuits, work opportunities for Black musicians did expand throughout the Americas. And this certainly contributed to subversion in the artistic field of racial hierarchies reconstructed after the end of slavery. In musical productions across the United States and Brazil, Black artists such as Scott Joplin (1868–1917), Marion Cook (1869–1944), Ernest Hogan (1865–1909), Henrique Alves Mesquita (1830–1906), Joaquim Antonio da Silva Callado (1848–1890), Patápio Silva (1880–1907), and Benjamim de Oliveira (1870–1954) moved successfully between the erudite and popular spheres. And their presence made a difference; even if Afro-descendant performers were forced to negotiate the traditional stereotypes of blackface, forms such as ragtime, tangos, cakewalks, and lundus gained new dimensions and meanings when they were protagonized by these talented musicians.

Despite racism and commercial profiteering, the musical field also expressed Afro-descendant struggles for equality and cultural valorization. As Paul Gilroy has argued (and Du Bois perceived much earlier), it never stopped being an important channel for the expression and communication of Black political identity across the Americas. Throughout the diaspora, slave songs and their musical legacy were essential to the struggle against racial domination and oppression and opened pathways for social inclusion and citizenship after abolition. It was thus not without reason that the Black leaders of the United States and the Caribbean chose Black music as a symbol of pride, identity, and authenticity in the political struggle against racial oppression.Footnote 17

In my search for the slave songs’ Atlantic connections and points of tension, I have chosen to focus comparatively on the Black musicians Eduardo das Neves (1874–1919) and Bert Williams (1874–1922) (see Figures 15.3 and 15.4). This choice deserves some explanation beyond the fact that the two Black singers were contemporaries who left similar archival traces or the existence of a relatively abundant bibliographical literature devoted to Bert Williams.Footnote 18 Recognized for their lundus and cakewalks respectively, each man was a protagonist in the birth of the recording industry in his home country, and both found ways to benefit from slave songs’ popularity in the cultural marketplace. Their trajectories demonstrate the degree to which the musical field became an important space for Afro-descendant representation and for the discussion – and subversion – of racial hierarchies.

Histories comparing the construction of racism in Brazil and the United States have generally emphasized specificities and differences, highlighting the role of explicitly oppressive legislation and violent Jim Crow–era exclusion in North America.Footnote 19 Without ignoring these unquestionable specificities, I seek here to call attention to important Pan-American commonalities in the experience of racism within in the musical field. Studies of the slave family, of enslaved peoples’ visions of freedom, and of freedpeople’s struggles for citizenship have already fruitfully explored Pan-American approximations; adapting this approach to the musical field helps us to better understand not only the actual history of slave songs in the so-called Black Atlantic but also that music’s place in national imaginations and the experience of racism after the end of slavery. The musical field in the southern Black Atlantic is a new and fertile field of historical study.

Although they moved in different worlds and genres, Black musicians such as Eduardo das Neves and Bert Williams faced similar obstacles in their quest to find space in the musical universe; they were dogged by racist attitudes throughout their careers; they had to deal with the derogatory images that illustrated the sheet music and playbills of the works they starred in; they had to respond artistically to maxims about the racial inferiority of Africans and their descendants wherever they travelled and performed; and they often had to resist pressure to give up their African cultural inheritance. Although he lived far from the Jim Crow laws, Eduardo das Neves also faced racism during his life and suffered from the numerous limits imposed on men and artists of his color in Brazil.Footnote 20 Like Bert Williams, he left perceptible traces of his political activism in the struggle against racial inequalities.

Even though they were in constant dialogue with racist iconography – and even though they often incorporated prejudicial representations of Africa and slavery – Eduardo das Neves and Bert Williams embodied forms of Black identity and musical expression that were no longer imprisoned in the masks of blackface or circus clowns. These artists radically negotiated, resignified, and subverted the powerful canons of blackface. Both men inverted and played with representations of Blacks and with the meanings of the masks of blackface, using their critical artistic sensibility to reinterpret the legacy of slave songs and racist theatrical conventions that identified Afro-descendants with stereotypical propensities for music, joy, naivety, indolence, and easy laughs.Footnote 21

Eduardo das Neves and Bert Williams were artists who knew how to find humor in difficult racial situations. Neves specialized in lundus, a musical genre full of humorous and ironic stories involving mulatas, love, and the everyday norms of Black social life. Williams, according to a New York Times obituary from March 4, 1922, was not seen as a “great singer,” but “he could ‘put over’ with great effect a song that was really a funny story told to music.”Footnote 22

Neves and Williams were born in the same year, 1874, and died not too far apart, in 1919 and 1922 respectively, a little before new genres such as samba, jazz, and blues began to be disseminated as national cultural emblems and celebrated as the musical expression of “Black people.” It is unlikely that they met personally, although they could have heard of each other through their managers or through their own exposure to transnational music. Cakewalk was part of the catalogs of the phonographic industry and circulated widely in concert halls in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

The two artists also became public successes at the same time, between the end of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth century. Although the modernities of New York and Rio de Janeiro diverged significantly – and although New York mobilized far more capital for cultural pursuits – both cities epitomized urban culture within their own national contexts. Williams and Neves rose to the top ranks of the recording and theatrical industries and were much applauded in their own time, generally by white audiences; and yet both men fell quickly into oblivion after their deaths.

Neves made his name in the circus and gained recognition through his prowess on the guitar, in theatres, and in musical revues; Williams began as a vaudeville performer. Williams also participated in films, and Neves edited collections of popular songs. Due to their success, they later became stars in the nascent phonographic industry, with an ample and varied repertoire that touched on a wide range of everyday themes but which also always engaged with the question of race.

Williams, it seems, had access to education and was born into a family with some resources. He also received international recognition during his visit to England, and after 1910 he was part of the Ziegfeld Follies, one of the most refined musical theatrical companies in New York. Neves never could have dreamed of such applause and recognition beyond the reputation he built from his phonographic recordings. He performed mainly in circuses, in charity balls, in variety shows, and in concert halls in Rio de Janeiro.

Despite these differences, I seek in this chapter to illuminate the parallels between the two men’s choices and actions. Their commonalities show how much Black artists across the Americas shared comparable experiences and constructed similar responses to the problems and challenges imposed on Black peoples during the post-abolition period. In a time marked by debates about the possibilities and limits of Afro-descendant citizenship and national belonging, men such as Neves and Williams took advantage of the nascent phonographic industry to expand opportunities for Black artists and widen the scope of theatrical representations of Blackness. No less importantly, their presence and protagonism helped ensure the ascension of their rhythms and tastes in the modern musical market.

Bert Williams, a Black Artist on Broadway

Although he was identified as an Afro-American and labeled himself a “colored man,”Footnote 23 Bert Williams was born in Nassau, an island in the English Caribbean. He arrived in the United States as a child and began his artistic life in California. From a young age he had been seen as a great artist and imitator, especially of Afro-American customs. He learned to play banjo early on and took part in minstrel shows all over the country, alongside both white and Black artists. After his first successes at the beginning of the twentieth century, Williams moved to New York.

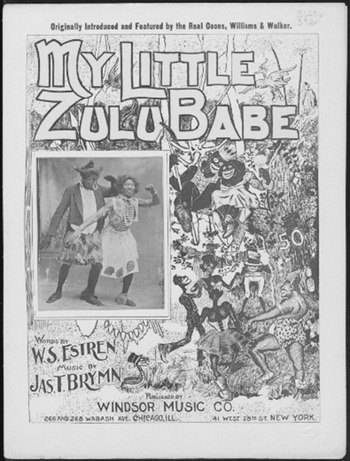

In the 1890s he began to share the stage with George Walker, a young Afro-American from Kansas; their artistic partnership continued until Walker’s death in 1910 (see Figure 15.5). The duo toured the United States, presenting Black songs and dances, which were great attractions for the minstrel shows’ white audiences. In 1900 the two artists were already recognized as talented comedians and disseminators of the cakewalk, both in theaters and in the international phonographic industry.

Figure 15.5 Williams and Walker. “My Little Zulu Babe.” https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/my-little-zulu-babe/12247.

In George Walker’s memoir about these early times – published in 1906 by Colored American Magazine – he revealed that the duo recognized and discussed all the wounds, persecutions, and prohibitions that plagued the professional life of Black musicians.Footnote 24 They were especially concerned with the success of blackface and the tunes known as coon songs. William and Walker made fun of these attempts at imitation, which they considered “unnatural.” But when they accepted the moniker “the two real coons,” they probably did so with the intention of showcasing Black talent and artistry.Footnote 25 When they reached New York, they found their first success with blackface performances in vaudeville and variety shows. Yet they always sought to present and represent – in a multifaceted and polysemic manner – Afro-Americans’ “true” and “authentic” artistic and musical abilities. Walker believed that white comedians were ridiculous when they converted themselves into “darkies,” painting their lips red and acting out exaggerated mannerisms for ragtime’s artificial scenarios.Footnote 26

Williams and Walker both achieved public recognition for their identification with Black musical and theatrical genres, although Williams enjoyed even greater success than his companion. According to a Washington Post article from November 10, 1898, Bert Williams “is one of the cleverest delineators of negro characters on the stage, and has no trouble at all in keeping his audience in roars of laughter.”Footnote 27 This success led the Victor recording label to invite Williams to record his repertoire at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Williams’ commercial recordings also had a longer life than Walker’s. Tim Brooks attributed Williams’ greater success to his unique vocal style.Footnote 28 Among the songs located by Martin and Hennessey from the first phase of Williams’s musical recordings (1901–1909), the standouts are comic takes on everyday troubles, such as lack of money, and satires of female behavior. Nevertheless, the songs’ titles immediately suggest that, when staged, many – some authored by Williams, some not – made what were probably meant to be humorous or ironic references to Africa, the “racial question,” the world of slavery, and the nature of Black men (this last theme was especially prevalent in the “coon song” genre): “My Castle on the River Nile,” “African Repatriation,” “My Little Zulu Babe,” “The Ghost of Coon,” “I Don´t Like de Face You Wear,” “Skin Lightening,” “She’s Getting More Like the White Folks,” “Where Was Moses When the Light Went Out” (a spiritual from the nineteenth century), and “The Phrenologist Coon.”

In the early 1900s, Williams and Walker also managed to produce their first pioneering Broadway musicals, which starred exclusively Black artists, breaking free of the limitations imposed by the ragtime “darky” style.Footnote 29 In 1903, In Dahomey opened; afterward came Abyssinia (1906), in which Bert Williams also participated as a composer and lyricist, and Bandanna Land (1908). The songs, librettos, and song lyrics – some of which had already been recorded – were authored by Black composers such as Will Marion Cook, Paul L. Dunbar, J. A. Shipp, and Alex Rogers. All were part of the artistic world of Harlem, where intellectuals, artists and musicians from the United States, the Caribbean, and beyond came together to transform the city of New York into the greatest center of Pan-African arts in the United States.Footnote 30 As Walker put it in his memoirs, Harlem was the rendezvous point for artists from “our race.”Footnote 31

Although these shows came in for their share of criticism, they were reasonably well-received by the general public. In Dahomey even traveled to London and gave a highly praised command performance for King Edward VII. Bandanna Land was even more successful: Theatre Magazine especially praised the singers’ performances and the show’s lack of vulgarity.Footnote 32

According to Walker’s 1906 memoirs, In Dahomey introduced a US audience to the novelty of “purely African” themes. Williams and Walker were, by their own account, pioneers in introducing “Americanized African songs” such as “My Little Zulu Babe,” “My Castle on the Nile,” and “My Dahomian Queen.”Footnote 33 However, despite this quest to expand the limits of Black representation, they could not avoid ending the show with a cakewalk, a convention that was considered obligatory for ragtime spectacles featuring “darkies” and “coons.” By the early 1900s, despite its subversive origins among nineteenth-century plantation slaves, the cakewalk evoked a certain nostalgia for old Southern plantation life and also guaranteed success to any Broadway show. The duo of Williams and Walker had made their name by performing cakewalks in the 1890s.Footnote 34

In Dahomey and Abyssinia showed once again the degree to which Williams and Walker engaged artistically with their era’s racial politics. They showed great familiarity with international debates and discussions among Black leaders in the US about the role of Africa and the African past in the history of Blacks across the Americas.Footnote 35 In Chude-Sokei’s synopsis, In Dahomey (1903) was about a dishonest group of Boston investors who proposed a great opportunity in Africa for the oppressed Blacks of the United States.Footnote 36 Walker, masquerading as the “Prince of Dahomey,” tries to convince hundreds of Floridian Afro-descendants to explore the wonders of his purported homeland. The song “My Castle on the River Nile” musically reinforced these dreams of wealth and power.Footnote 37 Abyssinia, from 1906, told the story of two friends (Walker and Williams) who, after winning the lottery, resolved to visit the land of their ancestors with some fellow African-American tourists. They had many adventures en route, even coming into conflict with Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia and being condemned in an Ethiopian court.Footnote 38 Not all the songs from these shows were recorded, but some from Abyssinia, such as “Nobody,” “Pretty Desdemone,” “Let it Alone,” and “Here it Comes Again,” were eventually distributed by Columbia.Footnote 39

In 1909 George Walker fell ill, and in 1911 he died. Bert Williams, after creating a few other shows with his troop of Black artists, embarked in 1910 for a career in the famous Ziegfeld Follies revue. In this company he worked for almost ten years among white artists, specializing in the original comic sketches that brought him his greatest success. In the Ziegfeld Follies he adopted the clothes that would become his visual trademark: a top hat, high-water trousers, and worn-out shoes. In general, he performed comic roles, poking fun at the misfortunes of taxi drivers, train porters, and poker players. He also touched on subjects of wide popular relevance, such as Prohibition and the question of US participation in the First World War.

During these years, Williams left most material related to Africa behind, but representations of slavery and race relations remained in his comic sketches and in a series of monologues based on folktales from the Afro-American tradition. Bert Williams seems to have continued to be a sui generis “real coon,” but he now performed the role solo in an outstanding Broadway company. Among his Columbia recordings from this phase, some dealt with Afro-American questions, such as those that recounted the history of a “trickster” called Sam; told of a slave who had made a pact with the devil (“How? Fried”); parodied the alleged superstition of Blacks (“You Can’t Do Nothing till Martin Gets Here”); and portrayed preachers and religious doctrines (“You Will Never Need a Doctor No More”).Footnote 40 “Nobody,” written at the time of Abyssinia, continued to be Williams’ greatest hit. Among his skits, “Darktown Poker Club” stands out because it allowed him to touch directly on racial stereotypes.

In the final phase of his life, between 1919 and 1922, Bert Williams continued to record discs and appear in shows, although he had by then left the Ziegfeld Follies. In his final years, despite widespread recognition and success as a recording artist (he was named a “Columbia Exclusive Artist” a little before the jazz boom), he also left indications of darker moments, due largely to the isolation he appeared to feel in the white artistic world.Footnote 41 In an autobiographical text, published in The American Magazine in January 1918, Williams reported that he was often asked “if he would not give anything to be white.” He had the following response:

There is many a white man less fortunate and less well equipped than I am. In truth, I have never been able to discover that there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have often found it inconvenient – in America.Footnote 42

Louis Chude-Sokei’s work highlights the fact that Bert Williams’ actions were not restricted to his stage successes. He also supported education and community development projects in Harlem, including the creation of the first Black National Guard in 1911 and the projected but never realized “Williams and Walker International and Interracial Ethiopian Theatre in New York City.”Footnote 43

Critical response to Bert Williams’ musical corpus was not unanimous, and observers have understood his contributions differently over time. Until recently, many observers and scholars criticized Williams for reproducing white stereotypes of Blackness. That interpretation does much to explain Williams’ relative obscurity after 1920, when Black intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance began to embrace another aesthetic that idealized the “new negro,” free of the masks of blackface. Other authors, however, argue that Bert Williams pushed the boundaries of prejudice and even transcended his racial condition, becoming a universally recognized comedian on the stages of the United States in defiance of prejudice and racial restrictions.Footnote 44

Williams’ Black contemporaries often saw him in a different and more positive light. Leading intellectual and activist Booker T. Washington, for example, wrote that Bert Williams had “done more for the race” than he had. James Weldon Johnson, a star of the Harlem Renaissance, recognized the global importance of ragtime and cakewalk, because they were Black genres that had conquered the United States, France, and the Americas. According to Johnson, Black artists such as Bert Williams had transformed blackface into the greatest performance genre in the United States. Even W. E. B. Du Bois recognized Williams as a great comedian and a “great Negro.”Footnote 45

Most modern scholars view Williams as a pioneering Black star of musical theater on Broadway and one of the most important architects of Afro-American theater. According to his best-known biographer, Louis Chude-Sokei, Williams knew how to transform the blackface space of representation, becoming the most famous “Black blackface.”Footnote 46 Through this “Black-on-Black minstrelsy,” he transformed the meanings of both the mask and the musicals themselves, introducing new themes and forging paths for many other Black musicians and artists such as Josephine Baker.Footnote 47

When worn by Williams, the mask of blackface was layered with other masks. It hid the artist and constructed a composite “negro,” divulging often-problematic notions about Blackness and Black identity.Footnote 48 But Williams managed to challenge and subvert both white representations of Blackness and Black self-depictions, thus inverting many of their meanings. According to Chude-Sokei, the blackface mask gained unprecedented political dimensions in the hands of powerful artists such as Williams, who played with what were seen as natural markers of Blackness and redefined the field of representation for US Afro-descendants.

A Black Brazilian Singer at Odeon Records

Eduardo Sebastião das Neves, later known as Eduardo das Neves or simply “Dudu,” was born in the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1874.Footnote 49 I have never managed to locate concrete data about his family background. Only his lyrics and stories allow us to establish some degree of connection to Brazil’s slave past and to social struggles such as abolition. Like Williams, Neves was popular among white and Black audiences and was admired by contemporaries,Footnote 50 although neither historians and musical memorialists nor leaders of Brazil’s Black movement have done much to preserve his memory for posterity.

In one of Neves’ first songbooks, he proclaimed himself the Trovador da Malandragem (“Trickster Troubadour”) and “The Creole Dudu das Neves,” which was also the title of one of his compositions.Footnote 51 The terrific lyrics of the unrecorded song “O Crioulo” can be read as a type of autobiography, in which Neves inverted the often pejorative meaning of the word crioulo, subverting racial stereotypes by confidently affirming his musical abilities and his capacity to attract the attention of mulatas, moreninhas, and branquinhas (all of whom served as muses in his songs).

“Dudu,” like various other musically talented Black men from his social background, started working at an early age, finding employment with the Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil Railroad and Rio’s Fire Department. He only dedicated himself fully to an artistic career after he was fired from both workplaces for bad behavior (which included participation in a strike and playing guitar while working). He began in the circus and made his stage debut at the Apolo Theater during the last decade of the nineteenth century.

Neves’ trajectory, like Bert Williams’, demonstrated considerable entrepreneurialism. He organized collections of popular songs and owned the Circo Brasil (a small circus); he also appeared as a performer at bars, theaters, charity parties, and cinemas.Footnote 52 With the title “Crioulo Dudu,” he cut an elegant figure, according to his sympathizers, in blue tails and a top hat. Many other Black musicians who gained commercial success took similar care with their offstage appearances.

In 1895, Quaresma Publishers released Eduardo das Neves’ first songbook, O cantor de modinhas brasileiras (The Singer of Brazilian Modinhas). The book referred to Neves as an “illustrious singer” and included lyrics for his repertoire and that of baritone and Black composer Geraldo Magalhães (who was well known for his maxixe performances in Paris). An advertisement for the Circo-Pavilhão Internacional, set up in Rio’s well-to-do Botafogo neighborhood at the end of 1897, shows that Neves was already a success in the circus ring, especially with a popular type of syncopated Afro-Brazilian music known as the lundu: “The premier Brazilian clown will provide the night’s delights with his magnificent songs and lundus, accompanied by his plaintive guitar.”Footnote 53

Other songbooks followed, and after 1902 Neves began his commercial recording career; he would also perform in many other circuses, revues, cinemas, theaters, and clubs. In the always crowded Parque Fluminense amusement and exhibition hall, he was advertised as the “Popular Singer Eduardo das Neves” alongside tenors, sopranos, and assorted curiosities and variety acts.Footnote 54

Neves’ songs, whether published or recorded, were part of a political and aesthetic idiom shared by music producers and the urban public at large. Like other Rio musicians, Neves recorded lovelorn modinhas, waltzes, serestas, choros, marchas, cançonetas, sambas, chulas, comic scenes, and especially lundus. He used music to promote republican political campaigns, paying homage to various national heroes. But he also made politics of music, writing songs that dealt humorously and ironically with topics such as the Canudos War, urban social tensions (“Carne Fresca” and “Aumento das Passagens”), obligatory vaccination campaigns, the proliferation of rats that spread bubonic plague, and the popular festivals of Penha.

Neves’ choices indicated an unquestionable awareness of the most important national and international topics of his day (he even wrote at one point about the Boer War in South Africa). In various statements, he expressed indignation at white Brazilians’ inability to recognize a crioulo’s capacity to discuss politics, elections, national customs, urban problems, and foreign policy. Neves proudly proclaimed his authorship of many of the songs he published or recorded. But among his successes, none could touch the song he wrote in honor of aviator Santos Dumont upon his arrival in Paris in 1903, when the entire city gave itself over to celebration.Footnote 55

Nevertheless, like Bert Williams, Neves also had the opportunity – and the choice – to articulate and enact slave songs, whose content and lyrics were directly linked to Black history, values, and customs. In the midst of Brazil’s national commemorations, Eduardo das Neves affirmed his identity as a Black man – “the crioulo Dudu.” His songs touched on racial identity and criticized racial inequality, in ways that indicate a desire to affirm the place of Black people and Black experiences in Brazil’s musical and theatrical worlds. Although his personal links to the experience of slavery are not clear, Dudu made a point of not forgetting Brazil’s slave past, consistently singing, recording, and publishing songs about enslaved people’s struggles for manumission, the abolition of slavery, and even the possibility of amorous relationships between Black men and white women. Beyond commemorating national heroes and exploring the everyday quirks and politics of urban life, Neves also touched with great irony and humor on Brazil’s Afro-descendant culture and history. Africa was not directly present in his repertoire the way it was in Bert Williams’. But African heritage appeared in recordings of musical forms such as jongo or in references to the dialects of African elders important in popular folklore and religion, such as Pai João, Pai Francisco, and Negro Mina. In his musical representations of slaves, Eduardo das Neves often appeared to wear the mask of the preto velho (literally the “old negro,” a term that could imply a stereotypical subservient slave). But in Afro-descendant religious and popular tradition, pretos velhos could also be storytellers, emblems of suffering and resistance, and carriers of African and Afro-descendant memory. And even as Neves mimicked their language and mannerisms, he also proudly broadcasted the musical innovations of their descendants.

Many of Neves’ songs touched on race relations in ways that could at once reinforce stereotypes and challenge racist theories or hierarchies of race and gender: examples include songs that recounted amorous relationships with iaiás, iaiazinhas, and morenas; the flirtatious provocations of crioulos; the superiority of the color black; and the cunning and ironic wit of Pai João (an iconic preto velho).Footnote 56 The recordings he made at the Casa Edison often include raucous laughter, shout-outs for crioulos and crioulas, and joyful banter among the musicians and other colleagues, who were known as baianos or baianos da guerra.Footnote 57

Among Neves’ songs, some of the most astonishing verses involved amorous relationships with iaiás (young girls, usually white) and morenas (women of mixed race) or odes to mulata enchantments. In Neves’ songbooks Mistérios do violão (Mysteries of the Guitar) and Trovador da malandragem (Trickster Troubadour), mulata and morena muses appear in “Carmem” and “Albertina.”Footnote 58 In “Roda Yáyá,” a mulata enchantress with links to the devil casts a spell on the protagonist – probably Neves himself – leaving him “captive and dying” from thirst. In musical response, Neves – calling himself a turuna (a strong, powerful, brave man, often a practitioner of capoeira) – proclaimed that the mulata would “fall into my net, and never escape from its mesh.”Footnote 59 As I have discussed elsewhere, Neves’ compositions, like most erudite lundus, deployed the mulata as an emblem of beauty and sensuality.Footnote 60 But in an important reversal, Dudu’s mulatas fall into the nets of cocksure crioulos rather than those of white slaveowners.

The crioulo’s flirtatiousness was even more astonishing in the verses aimed at sinhazinhas (young white women on the slave plantations). Assuming that Neves himself composed these verses, it is remarkable that a Black musician could depict himself directing seductive versus to a sinhazinha. It could be that such an exchange was considered so absurd that it was – in and of itself – the heart of Neves’ joke: the impossibility or improbability of such a situation made everyone laugh. At the same time, when Neves sang such songs, the sexual and racial inversion of the classic relations of dominance that had always paired white men with Black women gave such laughter undeniable political significance.

In Eduardo das Neves’ Casa Edison period (between 1907 and 1912), many of the lundus he recorded for the label revisited the theme of Black involvement with sinhazinhas, though the recording studio listed the songs’ authorship as “unknown.” In “Tasty Lundu,” Neves sung that he would go “to Bahia to see his sinhá” and “eat her dendê oil.”Footnote 61 The lundu “Pai João” paired similar temerity with an interesting resurrection of the preto velho, a literary figure already familiar in many songs and stories in both Brazil and the United States. The loyal preto velho never ran away – but in Neves’ rendering he also never lost his strength and audacity.Footnote 62 Neves’ Pai João refused to open his door to anyone while his wife Caterina was sleeping – not even to the police chief or his officers. But in a verse about Sundays, the singer seems to laugh as he sings that “when the master went out” he (Pai João) “took care of the beautiful iaiá.”Footnote 63

The preponderance of lundus in Eduardo das Neves’ recorded repertoire is especially interesting. The lundu was a musical genre especially associated with slave songs, usually performed for laughs in circuses or in phonograph recordings. But Neves’ appropriation of the form can also be understood as an original and powerful strategy to affirm Black artists and bring discussion of the racial question to a broader public sphere. It is important to remember that, during that time, Dudu’s comic and ironic style might have been the only possible way to discuss the Black experience and the problem of racial inequality in Brazil’s musical and artistic sphere. Just like the cakewalks and ragtimes of US blackface, the lundus had earned the affection of white audiences in the nineteenth century; they were part of a kind of blackface clown repertoire, were printed as sheet music, and appeared in malicious satirical verses published by refined authors in respected publications long before the advent of recorded music.Footnote 64 Because the lundu was understood as a form of comedy, it may – like its counterparts in the United States – have created a very particular way of projecting Black artistry into the field of entertainment, eventually constituting the form that came to be accepted and understood as “Black music.”

All the same, to extend Paul Gilroy’s observations south of the equator, Brazilian Afro-descendants could transform their performances on the stage and in the recording studio into an important form of political action.Footnote 65 Lundus provided Neves with commercial success and applause, but their intense polysemy also allowed him to invert and subvert the narrow and stereotypical roles traditionally allotted to Blacks. As Chude-Sokei observed about Bert Williams, Eduardo das Neves’s lundu performances were double-edged. On the one hand, he presented his audiences with visual and sonic images of comic, simple-minded Black slaves; on the other, he enacted clever, cunning, streetwise Black malandros, who seduced women of every color and articulated shrewd political and racial critiques. Even though Eduardo das Neves never incorporated the classical disguises of blackface – red lips, bulging eyes – he resembled Bert Williams in his ability to manipulate masks and embody contradictory double-meanings, thus subverting the norms imposed on Black performers who were identified with the cultural heritage of slavery.

Eduardo das Neves’ recordings of so-called gargalhadas (laughing songs) also had important points of intersection with blackface. Dudu’s most successful gargalhada was probably “Pega na Chaleira” (literally “Grab the kettle”), which satirized the kinds of political bootlicking and exchange of favors common in Brazil’s high society. Raucous, tuneful laughter (literal gargalhadas) appeared throughout the song. As it turns out, this genre was probably adapted from “The Laughing Song” and “The Whistling Coon,” which were recorded in the United States by George W. Johnson. A formerly enslaved man from Virginia discovered on the streets of New York, Johnson was likely the first Black musician to record for the phonographic industry in the 1890s.Footnote 66 Johnson’s “The Laughing Song” became a worldwide hit in the 1890s, eventually producing a remarkable 50,000 records that were sold in various parts of Europe and the Americas.Footnote 67 Johnson was also the author of a number of other international hits, including “The Whistling Coon,” “The Laughing Coon,” and “The Whistling Girl.” Johnson’s recorded laughter appears in a 1902 catalog from Casa Edison in Rio de Janeiro, in a recording entitled “English Laughter.”

According to the musicologist Carlos Palombini, the songs recorded by George W. Johnson made fun of Black people, just like blackface shows and “coon songs.” The gargalhadas recorded by Dudu, which were also cataloged as lundus, might have been inspired by Johnson’s style, but they expanded the satire to include the high politics of Rio de Janeiro. Regardless, the gargalhadas indicate that Eduardo das Neves knew Johnson’s recordings and sought to imitate them.Footnote 68 This suggests that he had heard of Bert Williams and understood the cakewalk’s multiple meanings.Footnote 69

Even after launching a recording career and embarking on very successful tours across Brazil, Neves never distanced himself from the circus. He achieved success with “singing pantomimes” in a wide variety of theatrical circus spectacles, showcasing a repertoire of happy, comical, patriotic ditties, many of which drew from the experience of slavery. Neves was certainly one of the best performers in this genre, along with Benjamim de Oliveira, another Black artist who had been born in slavery. Together – along with Black composer and conductor Paulino Sacramento – they produced multiple works, including a 1910 farce entitled A Sentença da Viúva Alegre (The Sentence of the Happy Widow), which was performed in the Cinematógrafo Santana. The cinema was located on Santana Street, near the famed Praça Onze, which was at that time Rio’s cultural ground zero for carnival groups and Black dance associations – Rio’s equivalent of Harlem. The “Sentence” was a parody of the operetta The Happy Widow by Franz Lehár, which had successfully opened in Rio de Janeiro in 1909, after its 1905 Vienna debut.Footnote 70

According to the music historian José Ramos Tinhorão, both Benjamim de Oliveira and Dudu used to paint their faces white in order to portray certain characters. In The Sentence of the Happy Widow, they did so while playing the rich widow’s suitors.Footnote 71 It would have been difficult for them to entirely control the audience’s reactions to Black men in whiteface, but there is no doubt that both men intentionally manipulated masks and stereotypical representations of whiteness and Blackness in order to elicit laughter from their audiences and irreverently invert racial hierarchies. Judging from newspaper advertisements, theirs were the star attractions among the farces and parodies performed in circuses across the city (see Figure 15.6).

As noted previously, songs protagonized by Pai João (or some other Pai) probably circulated widely in various post-abolition artistic and social circles.Footnote 72 Such songs were funny and ironic, but they allow us to perceive a figurative game of hangman in which the slaves’ desires (and possible those of the iaiás) became evident even as the slaves’ masters and future employers sought to prevent them from assuming their full shape. Based on these verses, we can surmise that poets such as Dudu used their music to explore the meanings of the slave past and the post-abolition struggle and to redefine race relations and Black identity. Beyond the artistic world, there are indications that Eduardo das Neves – like Bert Williams – cared deeply about defending the value of Black people and their history. He knew pioneering Black political figures of his generation, such as Federal Deputy Manoel Monteiro Lopes, and during civic commemorations of abolition he participated in events paying tribute to Afro-descendant abolitionists such as José do Patrocínio.Footnote 73 He fought for his rights when faced with racial prejudice and sought to claim his rightful place in the public sphere, most directly toward the end of his life when he sought entry into an important association of performing artists.Footnote 74 Neves’ most famous composition was a tribute to Santos Dumont, considered in Brazil to be “the father of aviation”; when its sheet music was published, the cover displayed not only the Eiffel Tower but also an image of Neves in the upper left-hand corner. Although the picture is small, it testifies that Neves sought to portray himself as a Black man who was modern, elegant, handsome, and thoroughly Brazilian.

But perhaps Eduardo das Neves’ commitment to the history of the Black population emerges most fully in his recording of the song “A Canoa Virada” (“The Capsized Canoe”).Footnote 75 A kind of popular ode to the abolition of slavery, the song musically commemorated the conquests of 1888, at least twenty years after the fact. The song used strong language that might have been unsettling for some of Neves’ contemporaries: the time had arrived “for the Black population to bumbar,” a verb that could mean both “to celebrate” and “to beat” or “to thrash.” Neves referred to May 13, “the day of liberty,” as a great moment of real change and dreams of freedom. Slavery was represented as a fragile vessel, a canoe that had literally capsized, ending its long Brazilian journey. The song ironically satirized the “haughty crioulos” who would no longer eat cornmeal and beans, and the “Blacks without masters” who were typical of many lundus – but it also celebrated the fact that “the day of liberty” had arrived, and there were no more reasons for “the Bahians to cry.” Black people, everywhere in Brazil, had longed for – and won – their “day of freedom.”

Eduardo das Neves also seemed unintimidated by crude and racist commentaries on his repertoire and personal style, even those written by well-known Rio intellectuals such as João do Rio and José Brito Broca. João do Rio wrote that he had seen Neves in the middle of the stage, in the midst of enthusiastic applause, “sweaty, with a face like pitch, showing all thirty-two of his impressively pure white teeth.” In Brito Broca’s prejudiced memoirs, the success of the popular Quaresma publishing house, which printed Neves’ songbooks, depended a lot on the “inventiveness of that flat-faced negro.”Footnote 76

Despite great success in his lifetime and the support of some intellectuals concerned with street folklore – including Alexandre Mello Morais Filho, Afonso Arinos, Catullo da Paixão Cearense, and Raul Pederneiras – Eduardo das Neves did not have his work recognized in posterity. Opinions about him, like those about Williams, are far from unanimous. In the Black movements that emerged in Brazil after the 1920s, Neves was scarcely remembered, perhaps due to his complicity with stereotypical representations of slaves and their descendants. Historians of music, in their rush to elevate the supposedly “modern” and “national” genre of samba in the 1920s – granted him no greater role. He was simply seen – or frowned upon – as an interpreter of comical lundus and jingoistic songs about republican heroes.

The only exceptions were a few of Neves’ contemporary Black intellectuals, who seem to have viewed Neves’ work and trajectory with admiration. For Francisco Guimarães, known as Vagalume, an important journalist and patron of sambas and Black Carnival groups, Neves had honored the “race” to which he was proud to belong. Vagalume called Dudu the “Black Diamond” and considered him to be a “professor” among samba circles.Footnote 77 There is also some evidence that Sinhô (1888–1930) and João da Bahiana (1887–1974), who would become samba stars in the 1920s, began their artistic life in Neves’ company. João da Bahiana, in an interview with Rio’s Museum of Image and Sound, declared that he had worked in Neves’ circus, leading the boys who animated his skits. Sinhô, who was anointed the “King of Samba” in the 1920s, accompanied Eduardo das Neves carrying the Brazilian flag during a famous tribute to Santos Dumont in 1903. Later, Eduardo das Neves would record three sambas attributed to Sinhô, before Sinhô was made famous with “Pelo Telephone” (“By Telephone”) which is remembered as Brazil’s first recorded samba. Neves’ final recording, released on April 10, 1919, was “Só por Amizade” (“Just for Friendship”), another samba by Sinhô. It was evident that new generations sought out Neves and that he, like Bert Williams, participated in the formation of future Black musicians.

Thanks to the work of the historian Felipe Rodrigues Boherer on Black territories in the southern Brazilian city of Porto Alegre, we know a little about Neves’ tour to that city in 1916. Although he suffered some uncomfortable embarrassments during his stay, Porto Alegre’s Black newspaper O Exemplo gave Neves a place of honor in its coverage.Footnote 78 The newspaper did not hide its pride in the singer, calling him a “countryman” and giving him the title of the “Brazilian nightingale” during his run at the Recreio Ideal Theater and the Sociedade Florista Aurora (a recreational association founded by the city’s Black population). Neves was part of a “chic program, featuring the very best of the esteemed artist’s repertoire,” accompanied by an orchestra and a society band.Footnote 79 The day after the opening, the paper announced that the presentation had been much appreciated and that the audience had not held back their “applause for the popular singer and countryman.”Footnote 80

In May 1915, during one of his tours through the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, the “Gazeta Teatral” column in Gazeta de Noticias stated that “Eduardo das Neves is an ingenious crioulo, the Monteiro Lopes of the guitar, the Cruz Souza of the stage, the Othello of the modinha.”Footnote 81 Like Bert Williams, Eduardo das Neves effectively “conquered” the public with his talent and his performances, leaving his mark on stages throughout Brazil.

Conclusion

Black musicians across the Americas may have made enormously varied musical choices. But the life experiences of Bert Williams and Eduardo das Neves indicate that neither the problems they faced nor the paths available to them were so very different. They both experienced profound continuities with the slave past even while surrounded by the novelties of the modern entertainment industry, grappling with old and enduring racist stereotypes about slave songs, Black music, and Black musicians. In seeking to transform both the legacy of the past and their place in post-abolition societies, Williams and Neves (re)created both the meaning of their music and the contemporary musical canon itself. In the midst of sorrow, prejudice, and forgetting, they won applause and recognition. Their very presence on the stage and in phonograph recordings was an important victory. Williams and Neves expanded the spaces available to Black musicians and actors, allowing them to become ever more visible in the circuses, bands, theaters, and recording studios that formed the backbone of the modern commercial entertainment industry.

The musical field thus occupied a fundamental space within the politics of Afro-descendant representation, exclusion, and incorporation (real or imagined) in America’s post-abolition societies. Representations of Black people and the meanings attributed to their music – in festivities, through carnivals or costumes, on the covers of musical scores, in sound recordings, or on the stage – could shore up the racial inequalities that reproduced themselves after the end of slavery. Inversely, however, they could also subversively amplify Black struggles for equality and cultural recognition, highlighting the cultural contributions of the descendants of slaves to modern American societies.