In the mid-1970s, the oil boom in the Arab oil-producing states resulted in a dramatic transformation of the economic and political landscape of the major labor-exporting countries of the Arab world, and Egypt is a prime example of this phenomenon. The quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 drastically altered the regional context in which labor emigration took place in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. In contrast to other regions, in MENA, the regional demand for labor was limited until the 1970s oil boom. As oil prices spiked in the aftermath of the 1973 war, huge revenue windfalls accrued to the oil-producing states like Iraq, Libya, and the Gulf States. Using these revenues, oil-producing states launched massive infrastructure and development projects that required more labor than the national states could supply. As a result, oil-producing states sought additional labor from outside to complete their projects. Arab workers spoke Arabic, were geographically close, and were abundant in number, and in the early decades following the oil boom, they proved to be ideal candidates to work in the petrodollar projects.

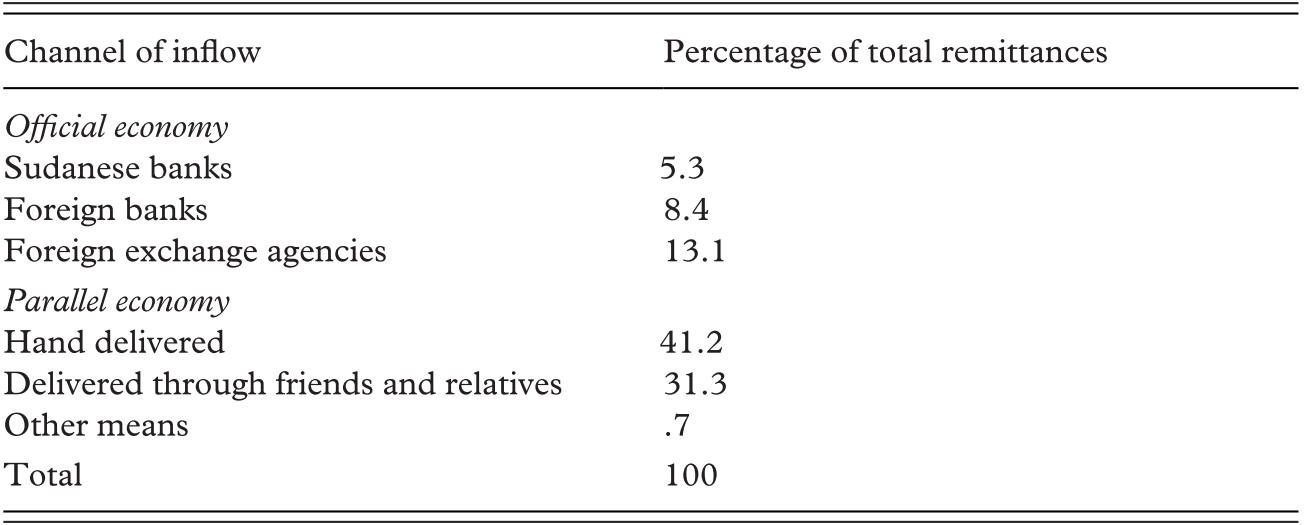

In Egypt, the combination of the jump in oil prices and the onset of economic reforms in the mid-1970s resulted in a dramatic emigration of Egyptians to the oil-producing states, and what became the largest source of foreign exchange: remittances. By the early 1980s, at the very height of the boom, there were an estimated 3 million Egyptians working in the Arab oil-producing states. Moreover, while in 1970 recorded remittances from migrant workers were estimated at US $30 million, by the early 1980s official government estimates of these capital flows ranged from US $3 billion to US $18 billion.1 The reason for the discrepancy in official estimates was that workers sent their earnings primarily through informal familial and friendship networks rather than through official banking channels. This was mainly because of the continued overvaluation of the Egyptian pound and the mistrust that many workers had of formal banking institutions back home. As in other labor exporters, the avoidance of official banking channels resulted in the emergence of a large “hidden,” or parallel, economy, in remittance inflows that were controlled by a network of currency dealers (tujjar ‘umla) who effectively institutionalized a “black market” in informal finance.

The economics and demography of transnational migration in the 1970s and 1980s illustrate with dramatic statistical details the larger story of the millions of unskilled and skilled and professional workers who traveled to the Arab oil-producing states to take advantage of new opportunities for work, welfare, and social mobility. However, as demonstrated by the sheer volume of remittances in this period, it is also important to emphasize that the majority of migrants did not cut their individual ties with their families back home.

Magdi Mahmoud Ali is illustrative of the fate of millions of youth (mostly young men) who emigrated during the oil boom in order to seek better opportunities in the oil-producing Arab states of the Gulf, Iraq, and Libya. Mr. Ali migrated to Libya in 1974 at the very beginning of the oil boom. He returned to Egypt nine years later because he lost his job as a result of the regional recession which led to the drying up of opportunities for labor migrants throughout the Arab region. Mr. Ali, a plumber by profession, departed his hometown of Marsa Matruh (in the Delta) in 1974. He first traveled to Libya, which he said at the time offered better opportunities for Egyptian labor migrants than the Gulf region. Like so many young men in the 1970s and early 1980s, Mr. Ali traveled illegally to Libya because, as he put it, “he had heard everyone [in Libya] could acquire a car and a nice apartment,” and added that “in Libya I earned between 5,000 and 6,000 dinars a month at a time when 1 dinar equaled three Egyptian pounds.”2 In 1987, Mr. Ali relocated to Saudi Arabia to work for a Public Water Works factory, worked and resided in Riyadh for two years, and then returned to Egypt in 1989. In the late 1980s, the combination of the effects of the regional recession and perceived domestic security threats compelled Gulf countries to implement new emigration policies that favored Asian over Arab labor. Consequently, Mr. Ali returned to Egypt in 1989 and noted that while he was earning 2,700 riyals a month in Saudi Arabia, he had to eventually leave the country since Asian workers who were brought in “accepted” wages as low as 700 riyals for the same position.

Importantly, like millions of young men working abroad, Mr. Ali did not cut his social ties with family and kin back home in Marsa Matruh. By his own estimation, he sent approximately 600 riyals a month to his mother and family, and he utilized two primary means to remit part of his earnings back home. The first method was to simply buy products and give them to Egyptian “suitcase merchants” (tujar al-shanta) traveling from the Gulf to Egypt who would deliver the equivalent value of the products in cash to his mother. The second means was more common in the 1970s and 1980s. This entailed the reliance on what Mr. Ali termed “personal contacts” who he would ask to deliver his remittances to his family directly thus evading the official banking system.

Mr. Ali’s experience as an expatriate worker, as well as the remarkable regularity with which he remitted part of his earnings back home to his family, illustrates the genuinely transnational social ties created by long-distance migration in the era of the oil boom. Indeed, Mr. Ali’s biography nicely dramatizes the direct linkage between the spike in oil prices in the mid-1970s and the central role that the boom in remittance inflows played for individuals and their families. But if Mr. Ali’s experience abroad illustrates one facet of the country’s (and indeed the region’s) political economy, Mr. Ali’s experience upon his return to Egypt, and specifically Cairo, exemplifies yet another phenomenon that altered the very nature and social and political fabric of urban life in Cairo: the boom in informal, unregulated, housing largely financed by the earnings of expatriate workers in the Arab oil-producing countries. Upon his return to Egypt in the late 1980s, Mr. Ali invested his earnings in an apartment building in Ezbat al-Mufti, one of the informal housing quarters in Cairo’s Imbaba neighborhood. He was not able to pursue his profession as a plumber with any regulatory since he had not only spent many years abroad but was also from the Delta region rather than Cairo and had no reliable social networks to find regular employment in his profession. Consequently, he was compelled to join the ranks of informally contracted workers in the construction sector. “Most of us,” he noted, “returned to places like Ezbat al-Mufti and had to work in construction. I do know some men who opened small workshops or a plastic company here but not many.”

The Remittance Boom and the Internationalization of the Economy

As Charles Tilly has noted in another context, the sheer volume of migrant remittances to relatively poor countries underlines the fact that migration flows “are serious business, not only for the individuals and the families involved, but also for whole national economies.”3 Indeed, Mr. Ali’s personal experience – his social and economic aspirations, humility, and hopes for success for himself and for his family – is one of the many individual backstories of the internationalization and the informalization of the Egyptian economy that began in earnest in the 1970s. These two interrelated changes in the country’s political economy resulted from the coincidence of exogenous economic shocks associated with the jump in oil prices as well as domestic economic reforms. These reforms are generally associated with revisions in laws governing foreign investment, trade liberalization, exchange rate adjustments, and the reorganization of the public sector. Understandably, Mr. Ali’s personal narrative focused on the immediate social aspirations and possibilities offered by out-migration, but it would not have been possible if it had not coincided with two important developments: the boom in out-migration and remittance inflows, and the economic opening (infitah) that President Anwar Sadat introduced in the mid-1970s.

Egypt’s economy was dramatically transformed in the mid-1970s as a result of the boom in oil exports and remittances. In his study of the country’s political economy in the era of the oil boom between 1974 and 1982, John Waterbury noted that while the regional labor market and the world petroleum market have always been intimately linked, “no one could have foreseen the exuberant growth in oil-export earnings and remittances after 1976.”4 Indeed, Egyptian international migration has always been affected by the labor market and political conditions in the receiving countries. While out-migration of Egyptians started in the mid-1950s, the real expansion of workers traveling abroad began in earnest after 1973. This was due to the dramatic hikes in oil prices in 1974 and again in 1979 that were accompanied by increasing demand for Egyptian workers in the oil-producing Arab states. In the era of the oil boom, millions of Egyptians migrated abroad in search of employment, but it is important to note that this takeoff in emigration was a result of internal and external factors. On the one hand, the vast wealth of the oil-producing states accelerated ambitious development programs that required increasing flows of labor. On the other hand, Egypt was witnessing high population growth and high levels of unemployment that increased incentives for both unskilled and new graduates to emigrate in search of employment. The combination of these “push” and “pull” factors resulted in a sharp increase in the migration of Egyptians. Only a small number of Egyptians, primarily professionals, had left the country in search of employment before 1974. But by 1980, more than 1 million Egyptians were working abroad, and that number jumped to 3.28 million at the peak of labor migration in 1983.5 The main destination of migrants was to the Arab Gulf states, followed by other Arab oil-exporting countries. By 1991, 53.3 percent of the total migrants were working in the Gulf countries, 32.9 percent in other Arab countries, and 3.2 percent in the rest of the world.6

To be sure, the boom in labor migration served to alleviate some of the pressure on domestic employment, but their departure resulted in an enormous “brain drain” for the country. This is because emigrants tended to be highly educated professionals, including doctors, engineers, and teachers. For example, one study that compared the educational levels of a large sample of nonmigrants and migrants estimated that 61 percent of migrants have secondary or higher education as compared to 53 percent of nonmigrants. This suggests that there is a high level of selectivity of migration by education. Moreover, individuals working in the public sector are less likely to migrate. Less than 8 percent of the migrants used to work in the public sector before leaving Egypt, compared to more than 27 percent of the nonmigrant group.7

Nevertheless, while the majority of expatriate workers tended to be generally more educated, their social profile reflected a distinct regional bias. Specifically, by the late 1980s, Egyptians living in the poorer and more rural parts of the country tended to migrate to the Arab Gulf in greater numbers than their urban counterparts. By 1991, migrants from rural areas represented 62.8 percent of those who migrated as compared to 37.2 percent of urban residents. However, it is important to note that these migrants represented both educated and illiterate Egyptians. Up to 1991, 30.3 percent were illiterate while 20.6 percent had a university degree and above.8 Moreover, since Egyptian migrants were often married males from rural areas who tended to work abroad in order to send support to their dependents in Egypt, the heads of households receiving remittances were less likely to be wage workers and more likely to be inactive or unpaid family workers.9 Understandably, millions of Egyptian households came to depend on remittances from family members. A study conducted in 1986/1987 in Minya government showed that remittances accounted for 14.7 percent of the total household income of recipients. Another study found that 74 percent of households receiving remittances use the money on daily household expenses, 7.3 percent use this money to build or buy a home, and 3.9 percent use remittances for the education of a family member.10

As millions of Egyptians came to rely on remittances from their expatriate relatives to invest in their family members’ education, welfare, and economic livelihoods, the cumulative effect of these capital inflows emerged as a central component of the national economy. Indeed, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, four major items represented the backbone of the national economy: oil, receipts from the Suez Canal, tourism, and workers’ remittances. Their share in total resources (gross domestic product [GDP] plus net imports) rose from 6 percent in 1974 to approximately 45 percent by the early 1980s. However, more significantly, by the mid-1980s remittances became undeniably the country’s major source of foreign currency. In 1984, for example, they amounted to US $4 billion equivalent to Egypt’s “combined revenue from cotton exports, Suez Canal receipts, transit fees and tourism.”11 Table 1.1 summarizes the balance of payments in the boom period between 1979 and 1985 and shows clearly the magnitude of remittances in the context of other sources of revenue. However, the volume of remittance inflows was far larger than those reported by official local and international sources represented in the table.12 This is because, as noted earlier, expatriate workers remitted part of their earnings back home, through informal, decentralized, and unregulated banking systems that were often, but not always, in contest with the state.

Table 1.1 Summary of Egypt’s balance of payments, selected years, 1979–1985 (in millions of US dollars)

| 1979 | 1985 | |

|---|---|---|

| Current account | 602 | 409 |

| Exports of goods and services | 589 | 897 |

| Tourism | 4,210 | 7,405 |

| Suez Canal | 5,401 | 8,711 |

| Other | 2,445 | 3,496 |

| Total | n.a. | 26 |

| Net current transfers | n.a. | 3,522 |

| Workers’ remittances | −1,915 | −4,735 |

| Other | −19.8 | −14.3 |

| Total | −11.2 | −13.6 |

| Current account balance | ||

| Trade balance as percentage of GDP | ||

| Current account balance as percentage of GDP | ||

It is important to emphasize that since all four main sources of revenue, remittances included, were exogenous sources (i.e., they had little relation to labor productivity in the country), they were highly vulnerable to external market forces, and engendered dramatic social and political changes beyond the control and purview of the state.

Infitah and the Politics of Economic Reform

There is a clear consensus that Egypt’s economy was dramatically altered in the mid-1970s as a result of the coincidence of two related developments: the oil price hikes that precipitated a boom in remittance inflows and economic liberalization initiated by President Sadat in the mid-1970s. Following the October 1973 war, domestic socioeconomic crises, as well as foreign policy considerations, led President Sadat to liberalize the Egyptian economy under a new policy of al-infitah al-iqtisadi (economic opening). John Waterbury has neatly summarized the main objects of the liberalization process in the 1970s: (1) to attract Arab investment capital from the oil-rich Arab states; (2) to encourage Western technology and investment through joint ventures with state-owned and private enterprises; (3) to promote Egyptian exports and privatization; (4) to liberalize trade through currency devaluation; and (5) to promote the “competitiveness” of public sector enterprises.13

In the 1970s and 1980s, however, the most important components of economic liberalization were based on the introduction of Law 43 in 1974, and its revision by Law 32 in 1977, and had to do with the desire on the part of the Sadat regime to attract foreign finance, particularly from neighboring oil-rich Arab states, and the need for providing financial facilities to foreign investors to attract them. Accordingly, among the key measures implemented by the Sadat regime was the invitation of foreign backs, incentive rates for the conversion of currency consisting of multiple (or periodically adjusted) exchange rates, moves toward the reorganization of the public sector, and tax exemptions and other privileges to foreign investors as well as the Egyptian private sector.14 Importantly, in order to offer incentive rates for currency conversion, the regime introduced the “own exchange” system to finance private sector imports. In sum, as Galal Amin has noted, “these laws provided for the opening up of the Egyptian economy to foreign investment, tax exemption for new investment, and the recognition that private companies would not be subject to legislation or regulations covering public sector enterprises and their employees.”15 Moreover, when Hosni Mubarak assumed power in 1981, he continued to promote these policies and further extended the liberalization of the national economy by taking steps to reduce the budget and external account deficits, thereby further reducing barriers to domestic and international trade.

It is important, however, to highlight two essential aspects associated with economic liberalization that reflect the overwhelming reliance and dependence on regional and capital markets resulting from the oil boom and the inflow of remittances. First, the country experienced far higher growth rates than in the etatist era of the 1960s under Gamal Abdel Nasser, but this was primarily due to revenue generated from exogenous sources rather than a result of an influx of private investment. Between 1972 and 1980, for example, the proportion of exports and imports of GDP rose from 14.6 to 43.8 and 21.0 to 53.0, respectively, and the average annual growth of GDP was 8 percent over this period. However, this growth was a result of the revenues from oil exports, Suez Canal receipts, tourism, and workers’ remittances. Revenues from these sources rose from $600 million in 1974 to an estimated $7.5 billion by 1983.16 Importantly, this growth was only partially accounted for by the influx of private investment, which registered only minimal growth in this period from 5.2 to 9.4 percent of GDP.17 Consequently, although Egypt experienced high rates of economic growth after the early 1970s, rapid rates of economic growth were dependent on “such sectors as housing and workers’ remittances which were temporary relief.”18 Indeed, by the latter part of 1981 the assassination of Sadat, the oil glut and global recession, and a high and growing level of imports placed Egypt in severe straits in its foreign exchange balances. In great part this was because worker remittances, tourism receipts, and earnings from oil and Suez Canal receipts fell sharply. By 1984, declining exports and rising imports led to a 30 percent increase in the trade deficit, ballooning to more than $5 billion.19

The second and related aspect of infitah is that as a result of the boom in remittances the state was able to retain significant authority over its national economy. As Waterbury has noted, the foreign exchange cushion afforded by remittance inflows and oil rents delayed further implementation of economic reforms until the 1990s and allowed Sadat to essentially maintain the Nasserist social contract and refrain from restructuring the national economy in this period. Indeed, the state was able to retain substantial capacity over its formal economy. In 1982, public expenditures stood at 60 percent, public revenues 40 percent, and the public deficit 20 percent of GDP. In addition, in 1978 the total fixed investment in public sector companies was LE 7.4 billion, the value of public sector production stood at LE 5.3 billion, and public sector value added at LE 2.3 billion. Three hundred and sixty companies employed more than 1.2 million workers. Thus, in the boom period the state was still the dominant actor in the economy in that it was essentially in control of public sector earnings, the marketing of agricultural commodities, petroleum exports, and the greater part of the formal banking system.20 The state also retained regulatory control over formal financial institutions. In 1983, the Egyptian public banking sector held its own against the onslaught of joint venture and private investment banks. “The four public sector banks in 1983, for example, had financial resources on the order of LE 14.5 billion as opposed to LE 5.1 billion in the private sector.”21

Indeed, despite the dominant discourse of infitah and economic liberalization that the Egyptian state followed, the regime pursued a gradualist approach to economic liberalization throughout the 1970s and 1980s. This approach characterized both the Sadat and Mubarak eras. As Eva Bellin has noted there were three primary reasons for this approach, which, in many respects, demonstrated the continued strength of the state and its autonomy from social forces during the early phases of economic reform. First, the very idea that economic reforms will produce economic growth and stimulate positive changes in society was weak among state elites and policy makers. Second, the government was intent on protecting fragile sectors of the economy such as the textile industry and agriculture against foreign competition. Finally, and most importantly, the fact that state-owned enterprises had served as a means of state patronage, that is, as an avenue to provide jobs for the masses and lucrative posts for the elite, the government was generally reluctant to privatize public sector companies. As Bellin has noted, “policies that seem economically irrational are crucial to the political logic of these regimes (providing patronage, sustaining coalitions, endowing discretionary power). As a result, a government would not be willing to undertake reform unless pressed by crisis; even then it is likely to hedge its bet and embrace, at best, only partial reform.”22

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the state followed a gradualist strategy that entailed reducing political tensions through a partial liberalization of the economy. As Harik has noted in a comprehensive study of infitah policies in this period, “the decision making power remained authoritarian and centralized,”23 and despite the emphasis on privatization, the bureaucratic apparatus expanded; many necessary goods continued to be subsidized by the government; and the public sector remained responsible for 70 percent of investment, 80 percent of banking, 95 percent of insurance, and 65 percent of valued added until the early 1990s.24 Moreover, not only did the state continue to dominate the industrial sector, by the end of the 1980s, the stated object of financial and trade liberalization of the economy was only partially achieved. There were still large price distortions of foodstuff, the foreign exchange rates remained unified, the Central Bank rate was still administratively controlled, and the nominal interest rates were far below the inflation rate.25 The government successfully resisted orthodox reforms by avoiding negotiations with the IMF and the agreements eventually reached with the IMF were only partly implemented.26

Indeed, rent seeking, or the diversion of state resources into private sector activities in return for political loyalty, constituted a major source of opposition to liberalization in the 1980s because bureaucratic elites were intent on “collecting rents on behalf of more highly placed patrons.”27 However, the reason state elites were able to maintain their patronage networks without little disruption had to do with weak capacity on the part of the Egyptian middle classes to decisively affect economic policy. A high level of fragmentation and ambivalence in society aided this autonomy of the Egyptian state from civil society. Indeed, the opposition Liberal party and Nasserist and Leftist parties in this period were not only weak and divided; they did not endorse wholesale liberalization and concurred with the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) in the belief that major components of state capitalism must be retained and this view was not opposed by the major opposition parties.28 For its part, the Muslim Brotherhood organization, the strongest opposition movement in civil society, while hostile to state’s involvement in the economy, was “ill-disposed towards reforms proposed by Western financial agencies.”29 A more important reason is that by the 1980s, the Muslim Brotherhood had established a number of Islamic economic enterprises and financial institutions and benefited greatly from the government’s economic reforms.

The Remittance Boom and the Informalization of Financial, Housing, and Labor Markets

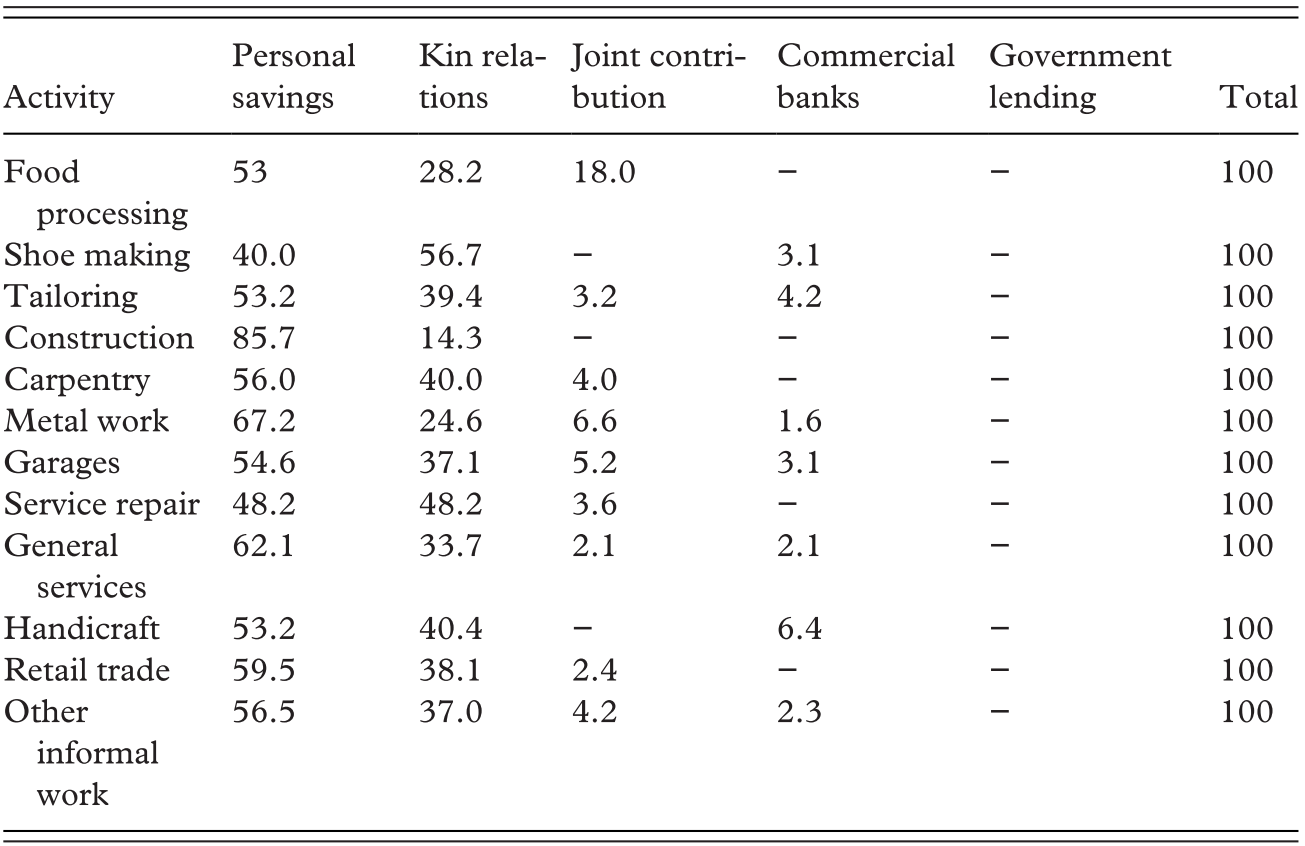

A key consequence of Egypt’s greater integration into the international capitalist economy in the 1970s, which played an important role in altering state-society relations, had to do with the increasing informalization of the national economy financed primarily by the boom in remittance inflows. To be sure it is important to note that as a result of the country’s centrally planned economy in the 1950s and 1960s, the “traditional” informal economy represented a key feature of the national economy. This “traditional” informal economy included a number of key components including smuggling, tax evasion, corruption, illegal transactions, a wide range of barter (i.e., nonmonetized) transactions, and small microenterprises that operated outside the purview of the state. As early as 1970, government estimates estimated that this informal sector represented between 25 and 30 percent of total industrial output in the formal sector.30

Nevertheless, there is no question that both the nature and volume of the informal economy expanded exponentially in the mid-1970s and that this was a result of both out-migration and particular aspects of economic reform. In one of the most commonly cited studies on the subject, Abdel-Fadil and Daib estimated various economic activities in the informal sector (or what they termed “black economy”), in 1980 at LE 2.1 billion, which at the time constituted more than 17 percent of GDP (see Table 1.2). Understandably, however, there are no agreed-upon estimates of the size of the informal economy in the 1980s. Indeed, other studies on the informal economy in the 1980s estimated that its value ranged from 35 to 55 percent of the total gross national product (GNP).31

Table 1.2 Values of transactions in Egypt’s “Black Economy,” 1980

| Moonlighting | LE 514 million |

| Tax evasion | 250 million |

| Hashish trade | 128 million |

| Profits on real estate speculation | 328 million |

| Customs evasion | 109 million |

| Informal housing construction | 260 million |

| Smuggling | 177 million |

| All sources total | LE 2.1 billion |

However, there is little question that the dramatic growth of the informal economy was the direct result of the migration of Egyptian labor and that it was primarily financed by the large volume of remittances that stemmed from out-migration. Indeed, the problem with estimates of the size of the informal economy at the time had to do with the fact that the financing of a wide range of informal economic activities flowed from remittances and these were impossible to estimate in a reliable fashion because these capital flows were transferred through informal means that evaded state regulation and official records.

As a consequence, two interrelated developments greatly accelerated, what I term, the informalization of financial, labor, and housing markets. The first, and most important, stemmed from the boom in remittances, the source of capital for much of the parallel economy and the institutional means by which remittances were transmitted, by the money dealers and Islamic financial and banking institutions. Moreover, like Mr. Ali’s personal story noted earlier illustrated, millions of Egyptian workers chose to evade official banks and financial institutions and sent their money back home to their family through intermediary moneylenders. This resulted in a dramatic expansion of a parallel market in financial transfers that evaded the regulation of the state. Moreover, while formal government records estimated the value of remittances at US $3 billion in the early 1980s, this vastly underestimated the true value of these capital flows precisely because they were sent via informal, decentralized, and unregulated channels. From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s remittances continued to rise, and by 1986 one study estimated that remittances from both official and informal sources stood at US $12 billion.32

The second by-product of the huge volume of remittances in this period was the expansion and informalization of the markets in housing and labor. Informal housing, defined as the construction of housing in formerly agricultural land without bureaucratic regulation, enjoyed a boom in urban and rural areas. This lasted until the mid-1980s when the regional recession resulted in the drying up of opportunities for migrant workers in the Arab oil-producing states. Between 1974 and 1985, for example, an estimated 80 percent of all new housing stock was built on formerly agricultural land and outside the purview of state regulation attesting to the central role that remittance earnings, unrecorded by official government figures, played in the expansion of informal housing.33

This boom in informal housing, financed largely by expatriate remittances, was due to the effects of economic reform as well as demography. Economic liberalization led to speculative land practices that resulted in the rise in the cost and demand for affordable housing, especially since housing that was provided by the public sector was neither sufficient nor desirable. More specifically, as one important study on the subject noted, the high value of the formal real estate market and the scarce opportunities for rents due to rent control laws, which left many apartments out of the market, meant that young people had no choice but to seek housing in the informal market.34 Nevertheless, it is also important to note that both the regimes of Sadat and Mubarak actively promoted this boom in informal housing for reasons of political and economic expedience in the context of economic reform. Indeed, it was not until the late 1980s that the state began to regulate new housing stock more vigorously. As I show in Chapter 4, this change in policy had much to do with what the state perceived as an Islamist “terrorist” threat emanating from these informal “slums.”

Nevertheless, what is noteworthy during the boom period is that growth in informal housing led to a dramatic rise in the number of informally contracted laborers, who entered the market in order to benefit from increased employment opportunities in the construction of informal housing financed largely by expatriate remittances. Informal, or casual, labor can be defined as work that is unregulated by formal institutions and regulations of society such as labor laws, registration, and taxation. Moreover, in the case of Egypt, the lack of a job contract and social insurance is how informal work is most usefully identified.35 There are no reliable official figures of informal workers in construction for the period. Nevertheless, there is strong consensus that informal laborers in the construction sector grew dramatically to meet the demand for housing in the informal areas (manatiq ‘ashway’iyya) in Cairo as well as in the rural parts of the country.

It is important to note that just as economic reform played a key role in the informalization of financial and housing markets, economic reform policies initiated by Sadat in 1973 resulted in the decline of public sector industries and opportunities available to workers in the formal economy. As McCormick and Wahba have noted in an important study, in the period of economic reforms the informal sector played an important role in job creation, and “new entrants to the labor market seemed to bear the brunt whereby by the 1990s, some 69 percent of new entrants to the labor market managed to only secure informal jobs.”36 Moreover, as one study noted, a great many informal workers reside in informal settlements because formal housing is not only unaffordable for low-income families but also too far from job opportunities for persons who rely on informal work for their livelihoods.37

What is important to note, however, is that while these markets are not regulated by the bureaucratic institutions of the state, they are nevertheless regulated by informal social networks embedded in local communities. Whether these social ties are organized around religious, regional, or ethnic ties, or served as avenues for nascent class formation depended on two elements: the type of market and the social character of the local community, and the state’s linkage and policy toward these informal networks in civil society. In the case of informal financial markets, these came to be organized and dominated by a network of currency dealers that entered into a battle with the state for control over this market. Moreover, while in the boom period informal housing was not registered or regulated by the state, these informal housing settlements were embedded in local social networks and affective ties. Finally, while informal labor is commonly defined in efficiency terms as a form of labor segmentation that is unregulated by formal political or social institutions, they are nevertheless regulated by social ties such as kinship networks, region, and sect.

Consequently, as I discuss in chapters 4 and 7, all three of these informal markets (i.e., finance, housing, and labor) came to serve as important avenues for social and political organization with important consequences in terms of altering state-society relations. This is because not only are these markets embedded in local communities and informal social networks, they are also intimately linked with formal state institutions in ways that resulted in very significant political developments at the level of both the state and civil society. In this respect, these informal markets represented different forms of commercial networks that played a key role in political developments in the country. Indeed, as Charles Tilly observed in his classical discussion of the political significance of informal commercial trust networks, even the most coercive rulers (i.e., rulers with high levels of state capacity in terms of their repressive apparatus and power to regulate the national economy) are routinely forced to both accommodate and attempt to regulate commercial networks in order to buttress their political power and legitimate their rule.38

A final dimension associated with economic reform is that it played an important role in the rise of a new phenomenon: namely a parallel economy in the provision of social, medical, health, and education services provided by Islamist groups in the country. These unregulated and largely unregistered Islamic Welfare Associations (IWAs) played an important role in mobilizing support among the urban middle classes. Along with the emergence of Islamic banking, IWAs came to represent a key component of a growing Islamic economy which, in turn, owed its growth to the dramatic increase in the volume of remittance inflows in the era of the oil boom.

The impetus behind the growth of IWAs had to do with the rapid deterioration in government-provided services. Government efforts to address this issue did not succeed but there is little question that the issue of welfare provisioning became a key concern on the part of state elites. This is clearly evidenced by the fact that the regime announced a five-year plan for 1978–82 that was supposed to establish priorities associated with welfare provisioning. However, the document did not effectively specify how this was to be achieved. This was designed to publicize the state’s commitment to the Nassserist social contract. In retrospect, however, it is clear that while the document falsely described Egypt as being in the “forefront of the welfare societies of the world,”39 the document was nothing more than an attempt to ward off popular discontent following the historic 1977 food rights precipitated by the withdrawal of subsidies on basic food items under the rubric of infitah. Moreover, production inefficiencies and administrative weakness lead to a deepening economic crisis in the 1980s with the result that the parallel and Islamic economy in Egypt emerged in the country and came to play an increasingly important role in the economy and helped to increase the popularity of Islamist groups.

Informal Finance and Islamist Politics: New Capital Flows and Islamic Management Companies

As noted earlier, etatist policies under the Nasser regime did encourage a wide range of informal economic activities. However, what made the 1970s different from previous decades is that the state’s capacity to regulate important sectors of the economy was greatly weakened. This was evident in two important and interrelated developments. First, the rentier effect of external sources of revenue resulted in a “dutch disease” element and led to the neglect of productivity issues mostly centered on formal public sector enterprises. Second, as the informal sector witnessed booming growth, financed by remittances, it had little capacity to siphon these capital flows into official state coffers.

Thus, economic reform policies in this period came to represent a paradox in Egypt’s political economy and, over time, greatly altered state-society relations. On the one hand, the state retained authoritative control over the formal economy and relative autonomy from societal forces. That is, the social contract whereby the state was committed to providing goods and services to the public in exchange for political quiescence was maintained. The state continued to control public sector earnings, the marketing of agricultural commodities, oil exports, and a substantial part of the banking system. The regime maintained its capacity over the mobilization of investment capital through the nationalization of private assets and the taxation of public sector enterprise. On the other hand, the country’s integration into the global economy, especially capital and labor markets in the Arab oil-producing states, narrowed its options and forced the regime to adopt policies that accommodated and even promoted the informal economy. More specifically, the internationalization of the economy led to a loss of state control over informal financial flows and created new paths for new capital (generated by remittances) to accumulate great wealth.

Indeed, as noted earlier, the primary goal of infitah was to lure Arab Gulf capital and Western development assistance into the country rather than internationalize the formal economy or privatize public sector industries. The primary goal was to apply selective economic reforms in order to encourage financial inflows without disrupting the state sector companies established under Nasser. A key example had to do with the state’s policies toward the dramatic expansion of the booming informal financial market stemming from remittance inflows.

The boom in out-migration and remittances provided a foreign currency cushion and acted as a social safety valve for unemployment. This, in turn, enabled the state to delay key economic reforms while simultaneously encouraging the inflow of financial inflows into the national economy. To be sure it enabled the regime to expand the private sector and begin to decentralize the country’s economic system. Nevertheless, it is important to note that while the policy of infitah resulted in some opening of the formal sector, private capitals flows were meager and were of a short-term nature and they were primarily directed into joint-venture banks, largely to finance imports. More significantly, the windfall rents accruing from remittances and oil exports enabled the regime to liberalize the banking sector, allow foreign banks to operate in foreign currencies, and relax foreign exchange regulations to stimulate a foreign capital influx. This led to the further internationalization of the economy in that it afforded Egyptians new opportunities to invest, speculate, and transact with the global economy without being forced either to deposit in public sector banks or to abide by the government’s overvalued exchange rates. There are many examples that demonstrate the ways in which millions of Egyptians took advantage of these opportunities. A man who owned a block of flats would rent one to an international bank, ask that the bank pay only one-third of the rent to him in domestic currency, and request that the remaining two-thirds be deposited outside the country in dollars.40

This in turn resulted in the erosion of the regime’s capacity to regulate a greater part of informal financial transactions. Much of Egypt’s new private capital, accumulated in the form of remittances from professionals, and laborers working in the Gulf States, might have siphoned into Egypt’s official banking, intensifying commercial competition, and strengthening a broad spectrum of infitah banks. However, various government restrictions in the official foreign exchange market, the overvalued exchange rate of the pound, and the incapability of the formal financial sector to cope with the requirements of emigrants meant that emigrants preferred to deal in the parallel (“black”) market because the latter offered a more favorable exchange rate than the formal banks. As a consequence, while the state retained control over capital accumulation in the formal economy, it lost control of large swaths of capital generated by informal financial circuits. Infitah, designed to attract foreign capital to invest in Egypt, became an open door for capital flight.

“Black Marketeers,” Islamic Banks, and the Rise of an Islamist Bourgeoisie

The combination of the expansion of informal financial markets as a result of the oil boom and economic reforms (i.e., infitah) resulted in the emergence of Islamic-oriented financial institutions in ways that greatly increased the economic prominence and political influence of a new generation of Islamist activists. Two institutions played a central role in these developments: the emergence of Islamic Investment Companies (IICs) and Islamic banks. In the 1980s, these Islamic financial institutions represented the rise and increasing prominence of a new Islamic economy, which in turn had a strong impact in altering the country’s political economy and ultimately expanding the scope and popularity of the Islamist movement in the country. More specifically, it reflected two interrelated dynamics in the country’s political economy: the erosion of the state’s capacity to regulate informal financial flows, and its struggle to retain its monopoly over the public sector while simultaneously seeking to encourage financial inflows and foreign investment, especially from the wealthy Arab oil countries.

The rise of the IICs, known at the time as Sharikat Tawzif al-Amwal (money management companies), was directly linked to the vast number of expatriate workers that migrated to the Arab oil-producing countries during the oil boom. As noted earlier, these workers faced the problem of sending a portion of their earnings to their families and so they quickly turned to foreign exchange dealers operating in the “black market” to channel their remittances. Since throughout the 1970s and 1980s the state maintained an artificially overvalued exchange rate, most expatriate workers chose to avoid using official banking channels since these “black marketeers” offered a rate far more favorable than the official exchange rate. By the late 1970s this informal, or parallel, market in foreign exchange reached an unprecedented volume, and it resulted in a broad organizational informal network that connected households in Egypt with the broader regional economy that consisted of banks and commercial networks in the Gulf. For their part, the currency dealers made enormous profits in two ways: by extracting a commission for their services and by profiting from the time lag in delivering the funds in local currency in order to make short-term interest profits. As in a number of other Arab labor exporters in the region, the boom in remittances combined with the heavy demand for the dollar back home resulted in a veritable bonanza for “black market” currency dealers who essentially came to monopolize the informal financial market.

As the expansion of this parallel market in remittance flows grew, it took on an institutional form in ways that eventually threatened the state’s capacity to regulate the financial sector of the economy. As the currency dealers grew in wealth, they established Islamic Investment Companies (IICs) in order to both continue to monopolize the inflow of remittances from expatriate workers and to invest these funds in commercial enterprises. These were “Islamic” investment houses in that they accepted deposits from expatriate workers, and they did so along the lines of Islamic principles in that they did so without going against the Islamic prohibition on interest dealing (riba). They also employed religious rhetoric to defend their activities and to encourage depositors working abroad to invest in these financial institutions. Nevertheless, it was clear from the onset that the largest of these companies were indeed established by prominent currency speculators. Two of the directors of the largest ICCs, al-Rayyan, as an important example, were well-known currency dealers in the late 1970s and early 1980s and were formerly listed by the Ministry of Interior as prominent currency dealers.

The rise of these IICs, which gained particular prominence in the mid-1980s, illustrates the importance of the parallel market in the country’s economy. This is because while these firms accepted a huge volume of deposits, they operated outside the system of state regulation, and they were not subject to the controls to which other banks had to submit. Indeed, they escaped any form of regulation and did not come under the monetary authority’s supervision or even company laws. In addition, their practices fell under parallel and often illicit black-market activities in the informal economy, for example, tax evasion, bribery, theft of state land, violation of import restrictions, and illegal foreign exchange dealings.

The Parallel Market and the Erosion of State Capacity: Informal and Formal Linkages

The continued resilience of the black market in foreign exchange and the prominence of the IICs in capturing the savings of expatriate workers led to two important developments. First, it further eroded the capacity of the state to regulate financial markets. Indeed, by the late 1980s informal finance was such a grave source of concern for the regime that the state-run media reported that, by escaping state regulation, IICs “dangerously” threatened the economic sovereignty of the state and undermined Egypt’s entire financial system.41 Second, these developments ultimately encouraged and promoted powerful elites within the Mubarak regime as well as a newly ascendant Islamist commercial bourgeoisie in civil society. What is most noteworthy is that in the late 1970s and throughout most of the 1980s informal financial institutions were not necessarily in contest or competition with the interest of state elites. Indeed, the linkage between the network of black marketeers that established the IICs and the state was evident in a number of ways.

First, a number of currency dealers operating in the parallel market were actually awarded significant loans in foreign currency from formal banking institutions, which they reinvested in their IICs. These loans were denominated in dollars, and the black-market dealers utilized these funds to import or smuggle goods into the country. Second, and perhaps most important, is the fact that the political influence of the black-market dealers became so dominant in the financial sector that they were able to strike back successfully against government efforts to reestablish Central Bank control over the financial sector. In 1984, as one key example, the Minister of the Economy, Mustafa al-Said, attempted to push through parliament legislation that would increase import restrictions, and give greater authority for the Ministry of the Economy and the Central Bank to regulate the private and joint venture banks that had been given special privileges, including tax exemptions and, most importantly, crackdown on the currency dealers. Subsequently, a number of the prominent black-market dealers were put on trial and charged with smuggling $3 billion out of the country.42 However, a week prior to the trial the network of black marketeers raised the price of the dollar 10 percent and openly called for the then Minister of the Economy, Mustafa al-Said, to resign from office. In essence, the black marketeers were able to raise the real price of foreign exchange a full 20 percent higher than the official rate and threaten the national economy. The monopoly of the black marketeers over the financial sector was so dominant vis-à-vis the power of the state that in April 1985, Mustafa al-Said was actually forced to resign after both the black marketeers and other business groups protested against new currency and banking regulations.43 Importantly, leading Islamists at the time also opposed the crackdown on the currency dealers and argued that al-Said’s crackdown was not waged in the public interest, but rather because his own business interests (and that of members of his family) were in competition with the informal financial market dealings dominated by the currency dealers.44 This incident not only illustrated the economic clout of the currency dealers, it also highlighted the fact that influential state elites were themselves profiting from black-market dealings at the time. Moreover, it also clearly showed that the state’s capacity to regulate the parallel market in remittances was crucially weakened. As an important study conducted at the time noted, this development clearly showed that the government’s goal of regaining control over the financial system in this period was more elusive than ever.45

By the mid-1980s the largest seven Sharikat Tawzif al-Amwal (al-Rayyan, al-Sharif, al-Sa’d, al-Huda, Badr, al-Hilal, and al-Hijaz) were in operation largely outside the purview of state regulation, and they had cornered the lucrative market on remittances from migrant workers. One study estimated that at their peak in 1985–86, deposits from expatriate workers to these firms stood at $7 billion. Yet another survey of the IICs, based on 1988 figures of the 52 IICs in operation, showed that the volume of remittances they attracted ranged from 3.4 to 8 billion Egyptian pounds, and this represented half a million depositors.46 Together with the Islamic banks such as the Faisal Islamic Bank and Al-Baraka Group, which were also promoted by the government to attract remittances, by the late 1980s, the Islamic sector had captured 30 to 40 percent of the market for household deposits and informal investments, and the informal Islamic economy was rivaling and possibly surpassing the formal sector of the formal Islamic banks and their branches.47 As the Egyptian economist Abd al-Fadil put it, “the struggle over the future of the Islamic money management companies was not simply a struggle over the future of the financial system and the means of mobilizing and investing remittances but a struggle over the very future of [Egypt’s] political and economic system.”48

Transnational Trust Networks and Legitimizing an “Islamic” Economy

An important reason for the great success of the IICs in attracting deposits from migrants in this period was simply because they distributed high rates of return, almost double of the official rate to their depositors. Indeed, as a number of studies have argued, the high interest offered by the IICs and the overvalued official exchange rate compelled millions of workers to channel their hard-won earnings into these unregulated financial institutions. Indeed, there is little doubt that rationalist and profit-maximizing calculations played a principle role in motivating depositors to invest in the IICs. Indeed, some of these companies offered high rates of return that stood at 24 percent per year, and some of the richest depositors received yearly rates of return nearing 40 percent.49 Nevertheless, it is also important to note that another reason for the IICs’ success is that they claimed to accept deposits along the lines of Islamic principles by claiming to prohibit usury (riba) in their transactions and by offering contracts based on Islamic precepts. As a result these firms came to play an important symbolic role in fueling the Islamicization of the economy in this period. Indeed, the prominence of these firms was also linked to the increasing popularity of the Islamist movement that was partially associated with the expansion of Islamic-oriented commercial networks and the rise and popularity of a new Islamic economy.

Indeed, what is often obscured in the studies on the IICs of the time is that it was not only Islamic rhetoric alone (i.e., the banning of interest in their operations) that facilitated the initial success of these firms; it was also due to the unregulated nature of these institutions. Depositors had to be sure that their earnings and investment would be secure and there could be no better “security” than in turning to the prevailing standards of interpersonal trust grounded in a shared commitment to Islam. To be sure, as Abdel-Fadil has aptly noted, the desire to generate windfall profits from their hard-earned savings was a key motivation for depositors to channel their remittances to the IICs. But if the economic incentive to generate wealth was an important consideration for depositors in choosing to transfer their remittances to the IICs, norms also played a role. Specifically, Islamic norms of interpersonal trust and trust worthiness, strongly promoted in the IICs’ media campaigns gave depositors a firm sense that their hard-earned earnings would not be squandered or misused by ostensibly like-minded pious Muslims operating these firms. In other words, while the transactions and deposits responsible for the growth of the IICs were unregulated by formal bureaucratic procedures and contracts, they were nevertheless socially regulated by Islamic norms and services that popularized these institutions and, as one scholar put it, made the “economic insecure seek a vehicle for forming [Islamic] networks based on trust.”50

Put in more economic terms, in the remittance boom decade of the 1980s, the IICs managed to foster notions of interpersonal trust that encouraged individual depositors to do business with these unregulated institutions in ways that reduced the costs of monitoring and enforcing agreements. This was necessary because the IICs essentially offered informal agreements that relied on religious affinities rather than on formal contractual obligations. Indeed, the important role of interpersonal trust in channeling remitted earnings to the IICs had to do with the “contracts” offered by these firms that were ostensibly based on Islamic precepts. The most common method was to simply inform the depositors that their invested funds would be utilized based on the principle of Mudaraba. In this case, the company would act as the Wakil (i.e., the trusted agent) of the depositor in the investment of his (or her) capital, and profit and loss was to be shared equally between the two partners. The depositor therefore had to essentially trust that the company would follow the guidelines of Mudaraba absent a formal contract since he was simply given a paper stating that the money would be invested along the lines of Islamic principles but any formal contract or government authority was dispensed with. Indeed, this was an important reason why despite the absence of formal guarantees and absent oversight and regulations, hundreds of thousands of expatriate workers deposited their remitted earnings into these investment companies.

It is important to note that the heads of these IICs were hardly operating in the interest of the depositors. By the late 1980s it was discovered that these firms had been running pyramid schemes. That is, they were paying investors high dividends on their deposits primarily by drawing on a growing deposit base rather than generating these funds from real assets. Nevertheless, throughout most of the 1980s these firms inadvertently played a role in fostering a transnational commercial network partially linked upon Islamic principles and ideals and thus they helped to popularize the idea of a new Islamic moral economy.

The IICs profited from their relationship to prominent leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood at the time in both economic and political terms. The Brotherhood’s networks in the Gulf and long-standing relations with Saudi Arabia at the time facilitated the operations of a number of the IICs, and there is evidence that some owners of the companies gave financial and political support to Islamist candidates in parliamentary elections.51 Moreover, in the context of rebuilding their organization, the Brotherhood was keenly aware of the need to adapt its internal structure to meet the opportunity of the internationalization of the economy accelerated by the liberalization of financial markets. Indeed, as early as 1973 the general guide (al-Murshid al-‘Am) of the organization, Hassan al-Hudaybi, began to promote and emphasize the international aspect of the organization as a way of asserting the Brotherhood’s leadership both inside and outside the country. In a general meeting of the organization convened in that year, Hudaybi reconstituted the Shura (Consultative) Council. He set up six membership committees in the Gulf region: three in Saudi Arabia, and one each in Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. These committees functioned mainly to ensure the Brotherhood’s “moral” presence and to secure allegiance to it, among Egyptians as well as the general populace of those countries. This reorganization proved to be instrumental in attracting strong financial backing for the Muslim Brotherhood by allowing them to serve as intermediaries between investment from the Gulf and domestic financial institutions. This period of wealth accumulation, ‘ahd tajmee al-tharwat as members of the organization termed it, made possible the promotion, expansion, and success of the Islamists recruitment campaigns.

The investment houses also fostered political linkages in order to solicit support from some leading individuals with close associations to the Brotherhood. A number of the big IICs including Al-Rayan and Sherif appointed leading Muslim Brotherhood individuals and Islamist preachers to serve on their executive boards as a way to legitimize the Islamic credentials of these companies. Some notable Islamist figures included the preacher Mitwalli al-Sha’rawi who joined the Al-Huda Company; Dr. Abd al-Sabur Shahin, a professor at Al-Azhar University, served on the board of al-Rayyan; and a leading Islamist, Salah Abu Isma’il, who was both an investor in and board member of the Hilal Company. Isma’il was a leading Muslim Brotherhood leader who was also elected to the People’s Assembly in 1984. Second, when in 1988 the government proposed legislation to regulate the IICs, prominent Muslim Brotherhood leaders, such as Shaykh Mohammad al-Ghazzali, not so much defended the IICs as institutions but rather the very idea of an Islamic economy. Ghazali, for example, argued that regulating these firms would force religious-minded citizens to deposit their savings in riba (i.e., interest) bearing accounts, while the respected Islamist intellectual, Tariq al-Bishri, noted that the campaign against the companies was a thinly veiled attempt by the Mubarak regime to undermine an emerging Islamist elite that represents a popular force in civil society.52

The more lasting and important link between the IICs and the Islamist movement had to do with the fact that the success of the IICs popularized the idea, in symbolic and practical terms, of building an “Islamic sector” of the economy to parallel and rival the state-dominated official sector. This idea became a key objective for a new Islamist bourgeoisie, which was not confined to the Islamic financial sector. It included investment in education and social welfare services all of which came to compete with the formal sector of the economy.53 The IICs, for example, invested in Islamic publishing, private education, hospitals, and medical clinics. This was clearly an effort to forge strong links between these institutions and important social groups in civil society, most notably the Muslim Brotherhood, and increase their legitimacy among the public.54 The funding of these activities was derived from two sources: profits derived from the “Islamic” economy that included the IICs and from voluntary donations in the form of zakat (religiously obligatory dues), which helped to finance a significant number of IWAs. The investments associated with the IICs also demonstrated a clear bias toward the commercial and service sectors of the economy and they demonstrated the role these investments played in promoting a middle-class commercial bourgeoisie. As Abdel Fadil has demonstrated in the most cited study on the subject, 49 percent of the IICs’ investments went to the tourism sector, 24 into housing, and focused on middle and upper classes. In contrast, only 4 percent went into industry and 9 percent into agriculture.55 Thus, the IICs did not only not make a contribution to development; they also buttressed and promoted the upper echelon of the Islamist commercial networks.

It is important to highlight, however, that most Islamist leaders defended the IICs on a number of religious and social grounds including the fact that they operated based on Islamic norms of trust and that they improved the livelihoods of millions of Egyptians abroad and at home. Throughout the 1980s prominent Islamist leaders were opposed to the regulation of the informal financial market. This was clearly evident by their position vis-à-vis the exchange rate. When, by the end of the decade, the IMF argued for the floating of the exchange rate and removing the multiple exchange rates system in place, Islamists leaders such as ‘Abd al-Hamid al-Ghazali of the Muslim Brotherhood and Magdi Husayn, both of whom were in favor of liberalizing other sectors of the economy, argued for the continued regulation of the currency. Ghazali, who in later years criticized the investment companies for their corrupt practices, in the early 1980s defended them and argued that removing currency controls would not eliminate the black market because Egyptians who engaged in activities such as tourism, the import of goods, and the haj would still resort to the black market since the “official” market would only sell foreign currency for certain purposes.56 What is significant, however, is that this call for the state to control the demand for foreign currency and foreign goods stood in stark contrast to the Islamists’ promotion of pro-market reforms, which included support for liberalized trade and investment that would remove any obstacles to Arab investments.

However, beyond the fact that Islamists supported the IICs at the time, there was a broader and more important issue. The investment houses represented the resurgence of civil society actors operating in the informal economy and as such represented the erosion of state capacity and the legitimacy of the regime in the context of newly resurgent social forces in society. Some of these forces were certainly linked to the Islamist movement but they also represented a wide range of groups in civil society (including millions of expatriate workers) who sought to challenge the state’s overwhelming dominance over society. For many, and not just Islamists, the parallel market represented a powerful economic alternative, which broke down the state’s monopoly over financial resources and allocation and could even help to usher in political pluralism.

Islamic Banking and the Dilemma of State Capacity

Another important factor that resulted in the increasing popularity of the Islamist movement and its legitimacy across a broad segment of civil society had to do with the rise and growth of Islamic banking in the 1970s and early 1980s. Islamic banks can be defined in similar terms as the IICs in that they pursued activities that they stated were in conformity with Islamic law (shari’a). More specifically, riba, the paying or receiving of a fixed interest rate, was replaced with the principle of musharaka, that is a partnership in profit or loss. Also, like the IICs the rise of Islamic banks was directly linked to the oil hikes and remittance boom.

The first Islamic bank to be established in Egypt was the Faisal Islamic Bank in 1979. Three other major Islamic banks followed: the Egyptian Saudi Investment Bank (ESIB), the Islamic International Bank for Investment and Development (IIBID), and Al-Baraka Group. As was the case with the IICs, the Islamic Banks were hugely successful in attracting deposits from expatriate depositors as well as financing from the Gulf. The success of these banks in attracting deposits was so significant that by 1995 other commercial banks opened an estimated seventy-five Islamic branches of their own institutions throughout the country.57 Between 1979 and 1986, the growth rate in the deposits to the major Islamic banks totaled an impressive 82 percent, which represented 9.8 of the total savings in the entire banking system. The Islamic banks were able to channel savings by offering higher interest rates on deposits than conventional banks, but they were also adept at encouraging deposits from migrant workers in the Gulf by offering accounts held in foreign currency. Consequently, by distributing returns quoted in foreign currencies rather than the deteriorated local Egyptian pound Islamic banks were able to encourage deposits from the millions of workers in the Arab oil-producing countries who were remitting part of their savings back home.

The success of the Islamic banking experiment represented the state’s somewhat contradictory relationship to the Islamist movement and, in particular, to the increasingly powerful Muslim Brotherhood. Moreover, in terms of the country’s larger political economy, Islamic banking represented the regime’s paradoxical relationship to the informalization of large segments of the national economy. Indeed, the state was intent on the liberalization of the financial sector and deregulating Islamic financial institutions in order to attract external finance and remittance inflows from expatriate workers, but as Soliman noted in one of the best studies on the subject (and in contrast to the case of Sudan addressed in the next chapter), the state retained considerable capacity to regulate these banks since the “visible hand of the state was behind [both] the foundation and promotion of Islamic banking in the 1970s.”58

On the one hand, the state was clearly intent on empowering the Islamists in the Islamic economic sphere. To be sure, the establishment of the FIB and other Islamic banks was part of the state’s infitah policy and was intended to encourage Gulf Arab investment. Indeed, state policy afforded Islamic banks special advantages over other state and private banks that played a key role in their expansion and success. In the case of the FIB, which served as the model for the other Islamic banks, for example, the regime enacted legislation that stated its assets could not be nationalized or confiscated, exempted the bank from official audits, and a series of taxes and custom and import duties, and it was not subject to the laws that controlled foreign currencies.59 The unintended consequence of this policy was to empower the role of the Islamists in the economy. Through their contacts in the Gulf, prominent members of the Muslim Brotherhood played a key role in establishing the FIB and they used their influence to ensure that prominent members such as Youssef Nada, Yusuf Qardawi, and Abdel Latif al-Sherif served on the board of directors of the bank.60 Another example is that of Abdel Hamid al-Ghazali. Ghazali, the Muslim Brotherhood’s chief economic thinker, was instrumental in establishing the IIBID. The strong involvement of prominent members of the Muslim Brotherhood in the initial phase of Islamic banking represented a honeymoon period between the state and their empowerment of Islamic finance and, by extension, the economic and symbolic influence of the Muslim Brotherhood.

On the other hand, what is noteworthy with respect to the role of the state and Islamic banking is that, in contrast to its permissive policy toward the IICs, the regime retained strong capacity in terms of regulating these Islamic banks. This can be discerned clearly in terms of the formal institutional linkages between the state and the Islamic banks, and the high degree of oversight that the regime retained over the banking system. Specifically, as of 1983 the Egyptian public banking system held its own against the joint-venture and private investment Islamic banks, and the four public sector banks had financial resources estimated at LE 14.5 billion as opposed to LE 5.1 billion in the private sector.61

In addition, the Central Bank and the Ministry of the Economy supervised the commercial activities associated with these banks. More importantly, the Minister of Interior kept a close watch over the role of the Islamists in these banks in case they posed a political threat to state “security.” In the 1980s out of fear of the strength of the Muslim Brotherhood, the then director of security, Fouad Allam, expelled members of the Brotherhood from the board of the directors of the Islamic banks.62 Moreover, just as the regime continued to regulate the expansion of Islamic banking to ward off both economic and security threats, the regime sought to retain an ideological stronghold over the very idea of “Islamic banking.” For example, it was the state-appointed Minister of Religious Affairs (Awqaf), Sheikh al-Sha’rawi, who submitted the legislation to parliament that sanctioned the establishment of the Islamic banks along with the privileges they enjoyed throughout most of the 1980s. Moreover, the Mubarak regime appointed a number of scholars from Al-Azhar University to preside over the administrative boards of the Islamic banks, and it established a number of government-funded institutions for the study of Islamic Economics. These efforts were all clear attempts on the part of the state to promote Islam as the legitimizing ideology of the state. The aim of these polices was to undermine the increasing popularity of the Muslim Brotherhood who by this time had generated a great deal of legitimacy in civil society.

The Emergence of an Islamist Bourgeoisie

There is a strong consensus that beginning in the 1970s the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood in particular experienced strong upward social mobility resulting from their success in private commercial business primarily because, under Nasser, they were barred from the public sector. Instead, they had to focus on the private sector once they were afforded the opportunity under Sadat’s open-door policies. By the 1980s, a number of Brothers were wealthy businessmen, and they had important connections to a score of others, many of these, like the construction Tycoon Osman Ahmad Osman, were connected to the organization. Osman was selected to lead the Engineers Syndicate once they took over that professional association. It is this commercial-business element that influenced the Muslim Brotherhood’s position with respect to pro-market reforms, black-market financial transactions, and the Islamic institutions more generally. Indeed, Omar al-Tilmasani, the leader of the organization, also supported infitah in his writings strongly and demanded more room for ras mal al-Islami (Islamic capital), which, in his view, included Islamic banks, the IICs, and the wide range of Islamic financial institutions of the Gulf countries.63 However, it is important to emphasize that Telmasani as well as other prominent Brotherhood leaders such as Yusuf Kamal and al-Ghazali defended this position in economic terms. Specifically, they argued that the debt crisis facing the country was due to “the corrupt centralized planning practices” initiated under Nasser, which created grave problems in the vast public sector, leading in turn to capital flight and currency speculation.64

Nevertheless, the spread of both informal financial houses and private Islamic banks helped to lay the foundation for the emergence of an Islamist wing of the infitah bourgeoisie, and they also financed the emergence of Islamist patronage networks that promoted the political profile of members of the Muslim Brotherhood. However, the growth in the Brotherhood’s financial and political clout in this period was crucially aided by the state’s promotion of a new Islamic economy. As noted earlier, from the perspective of state elites this policy was designed to fulfill two important goals: to lure investment from the Islamic countries of the Gulf and to build new clientelistic linkages with the Islamist movement in the country primarily so as to rival and outflank remnants of the Leftists and Nasserites in civil society. Indeed, just as Sadat cultivated the political support from the Islamists in the 1970s, in the 1980s the Mubarak regime encouraged the expansion of Islamic banking and, in doing so, effectively delegitimized the usury-operating formal banks. This, along with the initial success of the IICs, helped raise the popularity of the Muslim Brotherhood at precisely the time that they had embarked on a vigorous grassroots campaign to expand their popularity and constituency in civil society.

As Soliman aptly put it, the unintended consequence of these policies on the part of the regime was that the state, at least in this period, “empowered its own gladiator.” Indeed, along with the success of the IICs, the spread of Islamic banks and informal financial houses laid the foundation for the emergence of an Islamist-oriented middle class. The sectoral composition of the Islamic bank’s investment is one indication of this. On the whole the clients of Islamic banks tended to be urban merchants, as opposed to villagers. In addition, the banks showed no inclination to favor labor-intensive firms or investment in industry or agriculture. As one study noted, this was primarily because it was easier to follow Islamic prohibition on usury in the financial sector by simply claiming to abide by noninterest dealing rather than persuade investors of the efficiency and productivity of their investment in other sectors of the economy.65

Nevertheless, there are two reasons that an Islamist bourgeoisie emerged as a strong threat in the context of the infitah policies. The first, as described earlier, was directly linked to the opportunity afforded them by the influx of remittance inflows, their close ties to the Arab-Gulf economies and networks, and their prominent role, at least at the time, in establishing Islamic banks. The second reason for their relative success was rooted in the fact that the state, in its efforts to consolidate authoritarian rule, continued to heavily regulate other business groups as well as labor. The other business groups were relatively weak because they were small, heterogeneous, and represented corporatist associations linked to the state. Thus, while new groups such as the Commercial Employee’s Syndicate and the Engineers Syndicate emerged in the context of economic reforms, the state frequently intervened to curb any opposition by appointing ruling party stalwarts as the heads of these organizations.66 Similarly, autonomous labor unions were largely stifled from political opposition through coercive incentives. Specifically, in return for political quietism unions were allowed to utilize their pension funds to establish their own enterprises and enter into joint ventures with foreign capital.67

Indeed, under Sadat, and especially Mubarak, state policy reflected a paradox with respect to its changing economic and political strategies in the context of economic reform. On the one hand, it was intent on preserving its dominance over the economy and society by forging a strong alliance between the state, and foreign and private capital both to promote private investment in manufacturing and export sectors as well as to reassert its authoritarian rule over society. Mubarak did this by integrating local business groups such as the new professional syndicates and the Egyptian Businessmen’s Association as part of its development strategy.68 On the other hand, while the state remained in control over the formal economy and generally regulated business and labor groups, this resulted in the fact that the Islamist bourgeoisie emerged as a relatively strong force in civil society precisely because the business community remained weak and divided, and labor organization was forced to renounce demands for autonomous political expression since they became increasingly placed under the power of bureaucratic authority.

As a consequence, since business and labor represented corporatist groups linked to the state, newly emergent private and voluntary business organizations emerged. These were essentially the Egyptian Businessmen’s Association and the network of black-market money dealers. Bianchi has noted that these came to “represent important organizational responses of powerful segments of the business community in the context of the Mubarak government’s efforts to reorient Egypt’s open-door policy in the context of economic liberalization.” Business groups, organized around Islamist networks, came to have a great deal of economic clout in civil society.69