Across the Great Wall we can reach every corner in the world.

A Introduction

The regulation of data has increasingly become a common feature of trade agreements. To understand this rule framework, it is essential to first identify the main players and interests at stake. In my view, data regulation in trade agreements mainly deals with three groups of interests, each corresponding to different stakeholders. The first is the commercial interests of the companies engaged in electronic commerce. Due to the unique nature of their business, most Internet companies need unhindered data flows to conduct their business. Thus, they demand free flow of information across the globe and oppose to data localization requirements. Behind the second group of interest is the person or the consumer, who supplies the raw data to use the services provided by the Internet companies. As both the raw data and the processed data are controlled by the companies, consumers, at least to the extent they would act in their best interest, wish to ensure that their privacy and personal data are properly protected. This is where the third, and arguably the strongest, stakeholder – the state – comes into play.

The state monitors and regulates the data used by the first two groups, which involves the collection, processing, access and transfer of data. In designing the regulatory framework, the state often tries to strike a balance between the different or even conflicting interests of the different players, by trying to ensure the protection of the privacy of personal data, while not unduly hindering the development of the economy. Faced with various threats, such as cyberwarfare and terrorism, the state also needs to ensure that public safety and national security are not compromised by rogue players roaming at large in cyberspace.

While all regulators would agree on the need to strike a balance between the clashing interests of different stakeholders, their approaches often differ in practice. Some jurisdictions prioritize the need to safeguard the privacy of their citizens. A good example in this regard is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union (EU), which recognizes ‘[t]he protection of natural persons in relation to the processing of personal data’ as ‘a fundamental right’.Footnote 1 On the other hand, some jurisdictions put the commercial interests of firms first. In the United States (US), this is reflected in the 1996 Telecommunication Act, which notes that it is ‘the policy of the United States … to preserve … free market … unfettered by Federal or State regulation’.Footnote 2 In contrast, national security concerns are often cited to justify restrictions on cross-border data flow, albeit in varying degrees in different countries. A recent example is China’s 2017 Cybersecurity Law, which imposed several restrictions aiming to ‘safeguard cyber security, protect cyberspace sovereignty and national security’.Footnote 3

It is not easy to say which one is the best approach, as the various regulatory approaches often reflect the different legal, political, economic, social and cultural backgrounds of different countries. What is more important than passing judgement about different models, however, is to understand the inherent logic and mechanisms of the different regulatory regimes. In this chapter, I will focus on China, which is not only home to the largest e-commerce market in the world but also has one of the most tightly regulated cyberspaces. By providing a detailed analysis of the rationale and operation of ‘data regulation with Chinese characteristics’, the chapter seeks not only to help understand this discrete regulatory model but also to find ways to deal with such a regime at the international level.

B Internet Regulation in China

The first email from China was reportedly sent on 20 September 1987 by a group of researchers at the Institute for Computer Science of China’s State Commission of Machine Industry to the University of Karlsruhe in Germany.Footnote 4 On 28 November 1990, China’s national domain name – ‘.cn’ – was registered by Professor Qian Tianbai, a pioneer in the Chinese Internet industry.Footnote 5 However, it was not until 20 April 1994 that the first connection to the international network was established by China Education and Research Network, which marked the launch of the Internet in China.Footnote 6 Since then, the Chinese Internet has grown by leaps and bounds, despite occasional hiccups, such as Google’s exit from China in 2009.Footnote 7 In 2013, China’s e-commerce volume exceeded 10 trillion RMB and China overtook the United States as the largest e-commerce market in the world.Footnote 8 Nowadays, Chinese e-commerce giants like Alibaba are among the biggest online retailers globally and Chinese online shopping festivals, such as the Singles Day (11.11) Sale have gained loyal followers all around the world.Footnote 9 In the latest race on the research and applications of big data, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), China is also quickly catching up with the United States, a world leader that increasingly sees its competitive edge being narrowed.Footnote 10

Notwithstanding the phenomenal growth in the e-commerce sector, the Internet remains under tight regulation in China. The following section provides a detailed examination of this framework, paying specific attention to the regulation of data.

I Overview of the Regulatory Landscape

Just like the development of the Internet in China, the evolution of the regulatory landscape in China over the past twenty years is also a remarkable journey, where the haphazard regulatory patchwork was revamped in several iterations before culminating in one of the most sophisticated regulatory frameworks the world has ever seen. With the benefit of the hindsight, we can divide the development of the regulatory framework into four stages.

The initial stage was from 1987 to 1998, when the Internet was still in its embryonic stage and the government had yet to fully fathom its potential. Thus, the world wide web largely remained as the ‘wild wide web’ and untangled by regulations. This does not mean that there was no regulation at all during this period. To the contrary, two important regulations were introduced in the short span of one year – the 1996 Provisional Regulations on the Management of International Networking of Computer Information NetworksFootnote 11 and the 1997 Measures for Security Protection Administration of the International Networking of Computer Information Networks.Footnote 12 Yet, the regulatory framework in this period suffered from the following weaknesses: First, these regulations were very low in the legislative hierarchy, as they were provisional regulations and administrative rules issued by the executive branch, which did not have the same force as national laws issued by the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee. Moreover, these regulations were not made with the authorization of the legislature. Thus, at least in theory, these regulations could be challenged, especially with regards to provisions that contradicted the rules in legislations of a higher rank. Second, the regulatory framework was built in a piecemeal manner. There was no central agency coordinating the powers of the different agencies and no clear delineation of jurisdictions between the different agencies. This could potentially result in gaps as well as in overlaps in the regulatory framework, making the whole system rather inefficient. Third, these regulations all focused on the Internet hardware and there was no regulation on the software, not to mention content. Paradoxically, this contributed to the exponential growth of the Chinese cyberspace at the turn of the century, where people flocked in the pursuit of freedom of speech unavailable offline.

The second stage started with the establishment of the Ministry of Information Industry (MII) on 31 March 1998, which resulted from the merger of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (MPT) and the Ministry of Electronic Industry (MEI).Footnote 13 With an explicit jurisdiction over the information industry, the MII became the main regulator of the Internet in China.Footnote 14 However, other agencies quickly stepped into the cyberspace and started to compete with MII on the regulation of various issues such as online news, audio-visual services, online media and web security.Footnote 15 While these new agencies helped to fill the void in the regulatory space, their eagerness to capture more regulatory power also heightened the risk for potential turf wars. To address this, in 2001 the State Council re-established the National Informatization Leading Group.Footnote 16 Headed by then Premier Zhu Rongji, the Leading Group tried to coordinate among the different agencies. In November 2004, the General Office of the CCP Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued Opinions on Further Strengthening Internet Administration, which clearly divided the jurisdiction and responsibilities of all central government ministries and agencies involved in Internet governance.Footnote 17 However, as these agencies are all of the same ministerial rank, the problem of regulatory competition remained. This did not change until 2010, when the General Office of the CCP Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued Opinions on Strengthening and Improving Internet Administration.Footnote 18 Pursuant to the Opinions, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) was established in 2011 as a ministerial-level agency.Footnote 19 While its main jurisdiction is content regulation, the CAC also presides over the troika of Internet governance, which includes, in addition to the CAC: the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), which inherited the portfolio of the MII; and the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), which is responsible for Internet crimes and safety issues.Footnote 20

The third stage in the evolution of China’s cyberspace regulation was heralded in 2013 by the Third Plenum Conference of the Eighteenth Party Congress, which adopted the Decision of the CCP Central Committee on Several Major Issues concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform.Footnote 21 The Decision adopted the policy of ‘positive adoption, scientific development, lawful administration and ensuring security’ for the development of the Internet, and called for further strengthening of Internet governance, especially the further streamlining of its leadership system. Most notably, the Decision emphasized that the objective of Internet governance shall be ensuring ‘the security of national Internet and information’. This was the first time that Internet governance was elevated to the level of national security in a major Party document, and it set the tone for a new era of China’s Internet regulation.

In his report to the Third Plenum Meeting, President Xi covered eleven major issues, one of them being Internet governance.Footnote 22 He emphasized that Internet and information security is ‘a matter of national security and social stability, and a new composite challenge facing China’.Footnote 23 Xi also noted that the existing Internet governance system was lagging behind the rapid development of Internet technology and applications, and suffered from problems such as duplication and overlapping of agencies and their jurisdictions, mismatch between power and responsibilities, and low efficiency. According to Xi, to further strengthen Chinese Internet governance, the functions of the relevant agencies needed to be reshuffled to provide a comprehensive governance framework that covered everything from technology to content, and from ensuring everyday security to combating crimes.

Pursuant to the Third Plenum Decision, the Central Leading Group on Cyber Security and Informatization was established in February 2014.Footnote 24 The Leading Group is the third ‘super agency’ established after the Third Plenum Meeting, with the other two in charge of the most important topics – comprehensively deepening reform and national security, respectively. With President Xi as its head and Premier Li Keqiang as the deputy, the Leading Group has twenty-two members, which include three of the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee and nine of the twenty-five members of the Politburo. Eleven of its members are also members of the Leading Group on Comprehensively Deepening Reform, one is Secretary-General of the State Council at Vice Premier level, while the rest are all heads of important ministries, including the all-powerful National Development and Reform Commission. Such high-level set-up signals that cyber security and informatization have been elevated to an unprecedented level and have now become important components of the overall national security strategy.Footnote 25 While the Leading Group remains an ad hoc body, it now has an office housed at the newly restructured Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC).Footnote 26 This greatly boosted the status of the CAC among the peer ministries, as it is one of the few agencies under direct leadership of President Xi. In August 2014, the State Council even delegated its power on cyberspace content regulation to the CAC.Footnote 27 This made the CAC the most powerful agency with regard to the regulation of the Internet, and particularly with regard to Internet content.

The emphasis on cyber security was further confirmed by the 2015 National Security Law, which considers cyber security as a key component of national security and directs the state to make the ‘core technology of the Internet and information, key infrastructure and the information system and data in key areas secure and controllable’ in order to ‘protect national cyberspace security, safety and development’.Footnote 28 Moreover, Article 77 of the law requires all citizens and organizations to make timely reports on activities that endanger national security, truthfully provide evidence relating to such activities that one knows of, and provide the necessary support and assistance to national security agencies. If enforced strictly, the provision could be used to compel netizens to report ‘harmful information’ or activity in cyberspace, and throw China back to the days of the Cultural Revolution, where everyone was under the constant surveillance of each other. In practice, however, this clause has not yet been employed in such an aggressive manner by the authorities.

The evolution of China’s Internet regulation finally culminated in the 2016 Cyber Security law, which emphasized in the first article that cybersecurity is a matter of cyber-sovereignty and national security. The heightened role of the CAC was also further cemented by Article 8 of the law, which entrusted it with the overall responsibility for the planning and coordination of cybersecurity work and relevant supervision and administration, while the other ministries, such as the MII and MPS, are only responsible for the cybersecurity administration within their own jurisdictions.

II China’s Main Internet Regulations

From early on, the Chinese government recognized the disruptive potential of the Internet and put it under strict regulation. For example, barely two years after China was connected to the Internet, the State Council issued the very first Internet regulation – the 1996 Provisional Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Management of International Networking of Computer Information Networks (‘Provisional Regulations’).Footnote 29 According to Article 3, the Provisional Regulations apply to all international networking of computer information networks within China, which is defined as ‘networking of the computer information networks inside the People’s Republic of China and those in foreign countries with the purpose of international exchange of information’. The key provision is Article 6, which provides that ‘computer information networks shall use the international entry and exit gateways provided by the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications in the country’s public telecommunications network when they carry out direct international networking. No units or individuals shall be allowed to establish or use other channels for international networking without authorization’.

Anyone found in violation of the provision could be punished with a fine up to 15,000 RMB,Footnote 30 which was a hefty amount in 1996. With merely seventeen articles, the Provisional Regulations seem rather rudimentary, especially considering the fact that it dealt with such a complicated subject matter as the Internet. However, upon closer examination, we can say that it actually encapsulated all three aspects of Chinese Internet regulations for the decades to come.

The first is hardware regulation, which mandates that all Internet connections must go through official gateways sanctioned by the Chinese government. Such regulation enables the Chinese government to effectively control Internet connection, especially in blocking and filtering certain international websites and services.

The second is software/applications regulation, which means that even the software for Internet access must be sanctioned by the government. This is indicated in Article 10 of the Provisional Regulations, which states that all individuals, legal persons and other organizations must connect to international networks through access networks, which in turn are required by Articles 6 and 8 to connect through the Internet, i.e., those international gateways sanctioned by the MPT. This requirement is made explicit in the Implementation Rules for the Provisional Regulations (‘Implementation Rules’) promulgated by the Leading Group for Information Technology Advancement under the State Council on 13 February 1998.Footnote 31 After repeating the requirement to use official international gateways and the prohibition on using other gateways in Article 7, the Implementation Rules went on to state in Article 10 that all access networks to international networks shall go through the Internet and international network connections through ‘any other means’ are explicitly prohibited. According to Article 3.3 of the Implementation Rules, the international entry and exit gateways are ‘physical information channels used for international networking’. As Article 7 already explicitly prohibits the use of other physical gateways for connection, the interpretation of the law means that the term ‘any other means’ shall be interpreted broadly and includes other connection methods at both the hardware and software/applications levels. In other words, the term ‘any other means’ includes not only other physical gateways, but also ways to connect to the Internet through software such as virtual private network (VPN). This stringent requirement is repeated in Article 12 of the Implementation Rules, which further affirms that all individuals, legal persons and other organizations must connect to international networks through the access networks and not ‘any other means’.

The third category of regulation regards content. Again here, the essential rule framework on content is already found in the Provisional Regulations, which states in Article 13 that ‘the organizations and individuals conducting international networking businesses shall abide by relevant State laws and administrative decrees and strictly follow safety and security rules. They shall not use international networking for law-breaking or criminal activities that may endanger national security or divulge State secrets; or producing, consulting, duplicating or propagating information that may disturb social order or pornographic information’.

This strict regulation is also duly copied into Article 20 of Implementation Rules, with two small but significant twists. First, the subject of regulation expands from those conducting international networking businesses to the access units (Internet service providers, ISPs) and users. This makes sense, as the bulk of the content online is usually created by intermediaries and end users. Second, the same article also requires the three groups to immediately report any harmful information they discover to the relevant authorities and take effective measures to prevent the dissemination of such information. This is yet another important feature of Chinese Internet regulation that differs from other countries, especially the United States, which do not impose liabilities on ISPs pursuant to the ‘safe harbour’ rule. As we will see later, this approach has been extended to the regulation of data in recent years.

In the sections that follow, we examine the main Chinese Internet regulations along the three themes of hardware regulation, software regulation, and content/data regulation.

1 Hardware Regulation

According to Article 8 of the Implementation Rules, the nascent Internet in China is broken down into four networks: China Public Computer Network (CHINANET), China Golden Bridge Network (CHINAGBNET), China Education and Research Network (CERNET) and China Science and Technology Network (CSTNET), which are respectively administered by the MPT, the MEI, the State Education Commission, and Chinese Academy of Sciences. Among the four, the first two are commercial networks, while the last two are non-profit networks, which provide Internet services for the universities and research institutes under their respective jurisdictions. In 2000, China Mobile, the largest mobile company in China, also received approval to build an international Internet gateway.Footnote 32 To further regulate international gateways, the MPT issued Administrative Rules on International Networking Entry and Exit Gateways for Computer Information Networks,Footnote 33 which reiterated the prohibition on international networking through self-established international networking or other means including satellite.Footnote 34 The 2000 Telecommunication RegulationFootnote 35 also stated that all international telecommunication services shall go through the approved international gateways,Footnote 36 and explicitly prohibited operating international networking business through leasing dedicated international telecommunications lines, establishing relaying facilities without permission or other means.Footnote 37 To avoid confusion as to whether Internet services were part of telecommunication services, the Telecom Regulation also explicitly stated that both Internet connection service and Internet information service are part of value-added telecom services.Footnote 38

When China acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, the hardware restriction was also copied into its Schedule of Specific Commitments for Services, which notes that ‘[a]ll international telecommunications services shall go through gateways established with the approval of China’s telecommunications authorities’.Footnote 39 There was considerable confusion as to whether China’s commitments include Internet services. On the one hand, its commitments on value-added telecom services seem to include all the value-added telecom sub-sectors under the Services Sectoral Classification List – that is, h. Electronic mail; i. Voice mail; j. On-line information and database retrieval; k. Electronic data interchange; l. Enhanced/Value-added facsimile services (including store and forward, store and retrieve); m. Code and protocol conversion; n. Online information and/or data processing (including transaction processing). The only restriction seems to be that the services shall be provided through a joint venture with 50 per cent cap on foreign equity. On the other hand, China’s Telecom Regulations list Internet connection services and Internet information services separately from the value-added telecom services listed earlier. One may argue that one of the value-added services listed in China’s schedule – online information and/or data processing (including transaction processing) – has the CPC number 843**, which corresponds to online content services in the current CPC version.Footnote 40 However, a closer examination reveals that the correspondence is only superficial, as the two Internet services under the current CPC version correspond to 75231 and 75232 in the CPC provisional list (‘CPCprov’),Footnote 41 which is the basis of Services Sectoral Classification List and thus for the GATS negotiations and commitments. Class 7523 is defined in CPCprov as ‘data and message transmission services’, which in turn can be broken into Subclass: 75231 – data network services, and Subclass: 75232 – electronic message and information services.Footnote 42 However, according to the explanatory notes, Class 7523 only covers the necessary network services (mostly the underlying hardware) for data transmission, rather than the provision of information online. Thus, at most, China’s schedule would only cover Internet connection services but not Internet information services. However, even such an interpretation cannot get around the requirement to go through officially sanctioned international gateways, which is repeated ad nauseam in the regulations mentioned above and China’s GATS schedule.

2 Software Regulation

As mentioned earlier, the Implementation Rules prohibits connection to international networks through ‘any other means’, which could include software designed to evade official international gateways in addition to hardware. This is also copied into Article 59.1 of the Telecom Regulations, which prohibits the operation of international networking businesses through any means. The 1997 Measures for Security Protection Administration of the International Networking of Computer Information Networks provides further clarification by prohibiting unauthorized access to or use of computer information networks, which could cover access to international network using unauthorized software.Footnote 43

After Google pulled out of China in 2009, the Chinese government continued to tighten its control on cyberspace and blocked the websites of major social media (Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, etc.) and major international media (Bloomberg, Reuters, New York Times, etc.). To access these websites, many netizens resorted to VPNs. In view of this, the MIIT issued a notice in 2017, which explicitly prohibited VPNs.Footnote 44 To minimize the impact on firms, MIIT later clarified that foreign trade firms and multinational corporations could still lease dedicated lines for international networking from authorized telecom operators.Footnote 45 However, according to MIIT, such private networks can only be used for the internal office needs of the firm, and cannot be used to connect data centres or platforms abroad to conduct telecom businesses, which means that the lines cannot be leased to private consumers who are not employees of such firms. Since then, China has launched a major campaign to crack down on VPNs, and people have been jailedFootnote 46 and fined for selling and using VPN services respectively.Footnote 47

3 Content/Data Regulation

The main content regulation is the 2000 Administrative Measures on Internet Information Services,Footnote 48 which states in Article 15 that Internet Information Service Provider shall not produce, copy, distribute or disseminate information that is contrary to the basic principles laid down in the Constitution, laws or administration regulations; is seditious to the ruling regime of the state or the system of socialism; subverts state power or sabotages the unity of the state; incites ethnic hostility or racial discrimination, or disrupts racial unity; spreads rumours or disrupts social order; propagates feudal superstitions; disseminates obscenity, pornography or gambling; incites violence, murder or terror; instigates others to commit offences; publicly insults or defames others; harms the reputation or interests of the State; or has content prohibited by laws or administrative regulations.Footnote 49

Apparently copied from the Telecom RegulationsFootnote 50 and 1996 Interim Regulations on Electronic Publications,Footnote 51 the list has remained largely constant for the past twenty years. The only addition was made in 2002, when several regulations added a new category of ‘harming the social morality or the excellent cultural traditions of the nationalities’.Footnote 52 This new category, however, seems to be restricted mainly to online publications and has not been incorporated into subsequent laws and regulations. For example, neither the Administrative Measures on Internet Information Services nor the Telecom Regulations added this new category in their 2011 and 2016 amendments. It is also worth noting that such stringent regulation is not restricted to the Internet sector, as other regulations in the same period share the same restrictions on content.Footnote 53

One apparent gap in the 2000 Administrative Measures is that the rules apply only to Internet information service providers but not the users who generate such information. This gap was filled by the 1997 Measures for Security Protection Administration of the International Networking of Computer Information Networks, which expands the liability to ‘any organization or individual’.Footnote 54 In judicial practice, the offense of ‘Picking Quarrels and Provoking Trouble’ has also been invoked on a case-by-case basis against people posting information online about various social problems. One example is the case of Zhao Lianhai, who was jailed for two-and-half years for trying to collect information about contaminated milk with a self-built website.Footnote 55 In 2013, the practice was further institutionalized when the Supreme People’s Court and Supreme People’s Procuratorate jointly issued a judicial interpretation, which clarifies that posting defamatory information online would be subject to the offence of criminal defamation under Article 246 of the Chinese Penal Code.Footnote 56 Moreover, in recognition of the special nature of online information dissemination, the judicial interpretation also states that the defamation would be considered to be ‘serious’, if the information is clicked or browsed more than 5,000 times or forwarded more than 500 times.Footnote 57 In 2015, the Penal Code was also amended to add an additional clause in Article 291, which makes it an offence to fabricate information about natural disasters or crime and spread them online, or to spread such false information knowingly online. The issue was finally sealed when the new 2017 Cyber Security Law expanded the liability for prohibited online content from organizations to individuals, which was repeated in two separate provisions (Articles 12 and 48).

One could argue that such draconian laws on netizens are rather unnecessary, especially considering the fact that, unlike the United States, the Internet information service providers are directly liable for the contents generated by users. Under the 2000 Administrative Measures, for example, the Internet information service providers are required, upon discovering prohibited information on their website, to stop the transmission, keep relevant records, and report to the relevant state authorities.Footnote 58 To give real teeth to the requirement, Article 23 of the Administrative Measures also stipulates that Internet information service providers found in violation could have their licences revoked and websites shut down.Footnote 59

The liability for Internet information service providers was duly copied in the Cybersecurity Law.Footnote 60 Moreover, it went one step further by requiring Internet information service providers to establish mechanism to facilitate online complaints and reports.Footnote 61 A dedicated hotline and website (www.12377.cn) were also set up to handle reports on ‘illegal and unhealthy information’, with the first category being ‘political information’.Footnote 62 In 2018 and 2019, between ten million and thirty million reports were made on average every month, with the majority being directed against major social media sites, such as Weibo, Tencent and search engines, such as Baidu.Footnote 63

Another innovation in the Cybersecurity Law is the shift from the regulation of content to requirements on where such content, or data, shall be stored. According to Article 37, operators of critical information infrastructure are required to locally store personal information and important data collected and generated in their operations within China. If they need to send such data abroad due to business necessity, they have to first undergo security assessment by the authorities. This provision raised several concerns. First is what constitutes ‘critical information infrastructure’. Article 31 defines this as infrastructure in ‘important industries and fields such as public communications and information services, energy, transport, water conservancy, finance, public services and e-government affairs’, as well as such ‘that will result in serious damage to state security, the national economy and the people’s livelihood and public interest if it is destroyed, loses functions or encounters data leakage’. Such a broad definition could potentially capture everything and is not really helpful nor does it give much guidance, which is why the same article also directs the State Council to develop the ‘specific scope of critical information infrastructure’.

In 2016, the CAC issued the National Network Security Inspection Operation ManualFootnote 64 and the Guide on the Determination of Critical Information Infrastructure,Footnote 65 which clarified the scope of critical information infrastructure by grouping them into three categories: (i) websites, which includes websites of government and party organizations, enterprises and public institutions, and news media; (ii) platforms, which include Internet service platforms for instant messaging, online shopping, online payment, search engines, emails, online forum, maps, and audio video; and (iii) production operations, which include office and business systems, industrial control systems, big data centres, cloud computing and TV broadcasting systems.

The CAC also laid down three steps in determining the critical information infrastructure, which starts with the identification of the critical operation, then continues with the determination of the information system or industrial control system supporting such critical operation, and concludes with the final determination based on the level of the critical operations’ reliance on such systems and possible damages resulting from security breaches in these systems. More specifically, they listed eleven sectors, which include energy, finance, transportation, hydraulics, medical, environmental protection, industrial manufacturing, utilities, telecom and Internet, radio and TV, and government agencies. The detailed criteria are both quantitative and qualitative. For example, on the one hand, critical information infrastructure includes websites with daily visitor counts of more than one million people and platforms with more than ten million registered users or more than one million daily active users, or daily transaction value of ten million RMB. On the other hand, even those that do not meet the quantitative criterion could be deemed to be critical information infrastructure if there are risks of security breaches that would lead to leakage of sensitive information about firms or enterprises, or leakage of fundamental national data on geology, population and resources, or seriously harming the image of the government or social order, or national security. The potentially wide reach of the criteria was well illustrated by the case of the BGI Group, which was fined by the Ministry of Science and Technology in October 2018 for exporting certain human genome information abroad via the Internet without authorization.Footnote 66 Given the nature of their business, the BGI case could fall under the category of ‘leakage of fundamental national data on … population’, as mentioned earlier.

4 Summary

From the discussion on the remarkable evolution of Internet regulation in China over the past twenty-five years, we can distil two key trends: First, in terms of the institutional framework, we have seen the development from the period of no man’s land in the 1990s to the period of proliferation of regulation and regulators with overlapping and competing jurisdictions in the first decade of the new century. Since the beginning of the current decade, however, we have seen the power of Internet regulation consolidated under the CAC, which emerged as the dominating agency presiding over the troika of Internet governance, with the MIIT and MPS playing supporting roles. Second, in terms of the substantive regulations, we have not only seen the initial gaps in the regulatory landscape being filled with more and more detailed regulation, but also the shift in the regulatory focus. At first, the regulations focused on the technology, or the hardware of the Internet. Gradually, however, the focus shifted to the software, and then to the content, and now even to the data. This moves the regulations closer and closer to the heart of the matter, as the Internet, at the end of the day, is nothing but strings of zeros and ones arranged in specific sequences. With the adoption of the Cybersecurity Law in 2016, the focus has now been shifted to security, as the Internet is increasingly regarded as the key challenge to the all-powerful control of the Party. Thus, for China, Internet or data regulation has been presently elevated to a matter of national security. To put it in the words of President Xi, ‘there is no national security without cybersecurity’.Footnote 67 Moreover, he even linked the survival of the Party with the Internet, by solemnly warning in 2013 that ‘unless we solve the challenge of the Internet, the Party cannot stay in power indefinitely’.Footnote 68 The key to understand data regulation in China, therefore, must be ‘security’. The heightened link with security not only explains the domestic regulatory framework in China but also informs how China would deal with the issue at the international level.

C Trade Agreements

Ever since the Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce at the Second WTO Ministerial Conference in May 1998, WTO members have been exploring ways to incorporate Internet and data regulation into trade agreements.Footnote 69 While not much success was made in the WTO collectively, individual members were able to address the issue in other fora such as free trade agreements (FTAs) and the plurilateral Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) initiative.Footnote 70 It makes good sense to address the issue in international trade agreements, as the Internet was born with an international nature and closely linked to commerce. At the same time, however, a country’s position on Internet and data regulation in trade agreements is often heavily influenced by its domestic regulatory approach, and China is no exception.

In a way, China’s first encounter with data regulation in the WTO started on the wrong foot as it concerned a sensitive area: China’s regulation of publications and audio-visual products.Footnote 71 In the case, the United States complained that China has failed to grant foreign firms the right to import and distribute publication and audio-visual products. One of the key issues in the case was whether China’s commitments on ‘sound recording distribution services’ cover ‘electronic distribution of sound recordings’, as alleged by the United States.Footnote 72 China disagreed with the US approach and argued instead that such electronic distribution ‘in fact corresponds to network music services’,Footnote 73 which only emerged in 2001 and were completely different in kind from the ‘sound recording distribution services’. According to China, the most fundamental difference between the two is that, unlike ‘traditional’ sound recording distribution services, network music services ‘do not supply the users with sound recordings in physical form, but supply them with the right to use a musical content’.Footnote 74 In response, the United States cited the panel’s statement in US – GamblingFootnote 75 that ‘the GATS does not limit the various technologically possible means of delivery under mode 1’, as well as the principle of ‘technological neutrality’ mentioned in the Work Programme on Electronic Commerce – Progress Report to the General Council,Footnote 76 and argued that electronic distribution is merely a means of delivery rather than a new type of service.Footnote 77 Furthermore, the United States argued that the term ‘distribution’ encompasses not only the distribution of goods, but also distribution of services.Footnote 78 After a lengthy discussion covering the ordinary meaning, the context, the provisions of the GATS, the object and purpose and various supplementary means of interpretation, the panel concluded that the term ‘sound recording distribution services’ does extend to distribution of sound recording through electronic means.Footnote 79 China appealed the panel’s findings, but they were upheld by the Appellate Body, which largely adopted the panel’s reasoning.Footnote 80

The case was also the first WTO case concerning China’s censorship regime. It is interesting to note, however, that the United States did not challenge the censorship regime per se.Footnote 81 Instead, the United States only challenged the alleged discrimination in the operation of the regime, where imported products were subject to more burdensome content review requirements.Footnote 82 Ironically, the United States even proposed, as the solution to the alleged discrimination, that the Chinese Government itself shall shoulder the sole responsibility for conducting content review, rather than outsourcing it to importing firms.Footnote 83

With such an unpleasant experience, China took a cautious approach on the inclusion of Internet or data regulation in other trade fora. While it has signed more than a dozen FTAs so far, most of them have not included provisions on such regulations. The only exceptions are the two FTAs China signed with South Korea and AustraliaFootnote 84 in 2015 and the amendment of the FTA signed with Chile in 2018, which include stand-alone chapters on e-commerce. However, unlike the US FTAs, which often include provisions on free flow of data and ban on data localization requirements,Footnote 85 the earlier mentioned FTAs only address e-commerce-related issues, such as the moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions; electronic authentication and electronic signatures; protection of personal information in e-commerce; and paperless trading.Footnote 86 Thus, they do not really address Internet and data regulation issues as such.

A similar approach is taken by China in the WTO negotiations. Even though the United States has long been calling for rules on issues such as free cross-border data flow and ban on data localization requirements, China has ignored these issues until very recently. For example, in its communication on e-commerce jointly tabled with Pakistan before the Eleventh Ministerial Conference, China focused only on ‘cross-border trade in goods enabled by Internet, together with services directly supporting such trade in goods, such as payment and logistics services’.Footnote 87 As I have mentioned in another article, this approach is a reflection of the nature of business of most Chinese Internet firms, as they tend to focus on trade in physical goods facilitated by the Internet, rather than digital products like Google and Netflix.Footnote 88 Thus, when over seventy WTO members issued a joint statement on launching the negotiations on e-commerce at the Eleventh Ministerial Conference in December 2017,Footnote 89 China declined to join. When these members decided to formally launch the e-commerce negotiations in January 2019, however, China changed its position and jumped on the negotiation.Footnote 90 In April 2019, China issued a communication on the joint statement negotiation, in which it repeated the focus on cross-border trade in goods enabled by the Internet.Footnote 91 At the same time, however, it also addressed the main concerns of the United States, including data flows, data storage and treatment of digital products, in the following manner.

First, rather than ignoring these issues as it has done in the past, China chose to face them and acknowledge them as issues of concern for some members. This itself is a positive sign, as it indicates China’s willingness to engage on these issues. Second, at the same time, China also indicated that it was not ready to discuss these issues, at least not in the early stages of the negotiation. Citing the ‘complexity and sensitivity’ of these issues, as well as ‘the vastly divergent views among the Members’, China stated that ‘more exploratory discussions are needed before bringing such issues to the WTO negotiation, so as to allow Members to fully understand their implications and impacts, as well as related challenges and opportunities’.Footnote 92 Such approach is all too familiar to those who follow WTO negotiations closely, as it is basically a polite way of saying ‘we do not want to discuss these issues now’.

Third, in particular, China singled out the issue of cross-border data flows, by stating that ‘[i]t’s undeniable that trade-related aspects of data flows are of great importance to trade development’.Footnote 93 Interesting to note is, however, what China did and did not say in this sentence. It did not, for example, use ‘free flow of data’, which is how the United States has always referred to the issue in its submissions.Footnote 94 On the other hand, it qualified ‘data flow’ with ‘trade-related aspects’. This implies that China is not willing to address all kinds of data flows, just those related to trade. In other words, to the extent that some data flows do not have a trade nexus, they could be legitimately excluded. As I have mentioned elsewhere, this qualification could have wide implications, as it could be employed to justify restrictions on data flows in sectors that China has not made commitments, or even for those covered by existing commitments but provided free of charge (such as Google’s search engine services), as they are not ‘traded’.Footnote 95

Fourth, in an effort to turn the table, China also prefaced the discussion on these ‘other issues’ with the recognition that members shall have the ‘legitimate right to adopt regulatory measures in order to achieve reasonable public policy objectives’. This language is reminiscent of the calls for more ‘policy space’, a term often employed in trade negotiations to justify special and differential treatment and resorting to exceptions clauses. As the China – Publications and Audiovisual case mentioned earlier has illustrated, China will, most likely, invoke the public order exception contained in the general exceptions clauses of both the GATT and GATS to justify its online censorship regime. In particular, regarding data flows, China emphasized that it ‘should be subject to the precondition of security’ and should ‘flow orderly in compliance with Members’ respective laws and regulations’. This extends China’s domestic narrative of cybersecurity to the international level, which is made complete with the earlier reference for all members to ‘respect the Internet sovereignty’ of other members. By elevating the issue to one of ‘sovereignty’, China has shown the seriousness it attaches to the issue of regulating data flow.

In summary, China has made it clear that it is not yet ready to discuss these sensitive data-related issues, at least not in the early stages of the negotiations. There is a possibility that it will consider some of them further down the road, but such negotiations will not be easy given China’s guarded position.

D Conclusion

When people discuss data regulations today, they tend to focus on two main players: the UnitedStates, which calls for free flow of data to serve the interests of firms, and the EU, which prioritizes the need for the protection of personal information and privacy of the consumers. This chapter discusses the third major player – China – which emphasizes data security and even regards it as a matter of national sovereignty. Of course, such a regulatory approach was not formed overnight. Instead, the earlier discussions have illustrated how data regulation with Chinese characteristics has evolved over the past twenty-five years. More specifically, the analyses in this chapter have shown the differing regulatory logics and approaches at two different levels – the national and the international.

First, at the domestic level, we have seen Internet regulation shifting from hardware to software, and now to content and data. The shift in regulatory focus closely follows the development of the Internet in China, where it started as a novelty that was confined to the ranks of tech-savvy geeks, then gradually expanded to the masses with the proliferation of software and apps catered to popular uses, and now permeates everyone’s daily life from socializing and shopping to entertainment and education. Recognizing the central role played by the Internet in modern life, Chinese regulators have shrewdly chosen to regulate data, which is the essence of cyberspace that powers everything, especially with the rise of big data and artificial intelligence. Moreover, data regulation has now been elevated to the level of national security, and the agency that is responsible for content regulation, the CAC, has also evolved into the super-agency that is almost synonymous with data regulation in China. The CAC has no responsibility in promoting the growth of the sector. Instead, its only responsibility is making sure that the cyberspace is secure and nothing unexpected pops up. It is this single-minded pursuit of security that has led to such draconian policies as Internet blockage, filtering and other restrictions on the free flow of data, forced data localization requirements and the transfer of source code. As the Internet is becoming more complicated and omnipotent, we can only expect Internet and data regulations in China to become more sophisticated and omnipresent.

Second, at the international level, due to its unpleasant experience in WTO disputes, China has for a long time been rather cautious in addressing Internet and data related issues. This approach is also reflected in its free trade agreements, which tend to avoid the Internet-related issues. Even though its most recent FTAs – especially the ones with South Korea, Australia and Chile – started to address them, they tend to focus on only e-commerce-related issues and do not really address data flows. At the same time, in contrast to its defensive position on data-related issues, China has been quite aggressive in pushing for liberalization of ‘cross-border trade in goods enabled by Internet’. This reflects China’s interest as the leading goods exporter and the success of its e-commerce platforms such as Alibaba. In its latest proposal on the WTO Joint Statement Initiative on e-commerce, China started to address data regulations, but they were framed as secondary issues that require ‘more exploratory discussions’ and are subject to each member’s ‘right to regulate’ to achieve other policy goals, especially security.

The growth of the Internet in China over the past twenty-five years has not only led to the phenomenal growth of its e-commerce market, but also gave China the confidence and power to export its model, and to ‘set the agenda and make rules for cyberspace at the international stage’, as per the high-level exhortation by President Xi at the Politburo’s Thirty-Sixth Collective Study Session on ‘Implementation of the Internet Power Strategy’ in October 2016.Footnote 96 The success of China’s e-commerce sector will make the Chinese model attractive to many developing countries, as many of them are trying to emulate the accomplishments of China. However, an argument could be made that given China’s huge population base and the resulting enormous market, its e-commerce success story is more ‘in spite of’, rather than ‘because of’, the tight grip on cyberspace by the government. Nonetheless, given China’s growing economic clout, data regulation with Chinese characteristics is something that the rest of the world must grapple with for some time to come. It is in this regard that this chapter tries to make a distinct contribution by offering a preliminary peek behind the cyber curtain, while also offering some hints on the things to come.

A Introduction

In the past two decades, the rapid development of the Internet allowed the growth of e-commerce, and together with the new digital technologies and the Internet of Things, the flow of data – both commercial and personal has increased to levels unseen before. Traditional trade rules could serve as a starting point to deal with these issues but they clearly are not enough. To provide some context, in 1994 – at the time the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its agreements were established by the Marrakesh Agreement – Mosaic was the most used web browser on the Internet. (Netscape Navigator was created the same year, and Internet Explorer was only released in 1995.)Footnote 1 Neither Google, nor Amazon or Facebook existed in 1994. The ‘modern’ rules of trade law were not designed having taken into account the characteristics of contemporary digital trade and data flows.

This situation has led to the regulation of electronic commerce today becoming one of the most important topics in trade law and policy. Efforts of dealing with these issues at a multilateral level started in 1998, when the WTO established a work programme on electronic commerce and at the ministerial conference that same year, members agreed on a temporary duty-free moratorium on all electronic transactions – a practice that since then has been renewed at each WTO ministerial conference.Footnote 2 Further development has been slow paced and we are still far from achieving consensus on this topic. Only in December 2017, forty-four WTO members made a joint declaration to initiate exploratory work together toward future negotiations on trade-related aspects of electronic commerce.Footnote 3 In 2019, some countries like India and South Africa argued that the e-commerce moratorium in the WTO led to loss of revenue, as it gave such transmissions immunity from taxation, and initially opposed to the renewal of the duty-free moratorium.Footnote 4 And while there has been a new reinvigoration under the 2019 Joint Statement Initiative with currently seventy-seven WTO members on board, overall, until now, the WTO has made no substantive progress on e-commerce, and countries have not been able to agree on a multilateral regime for the treatment of e-commerce and data flows.Footnote 5

But the lack of consensus at a multilateral level does not mean that rules for digital trade are not being created elsewhere. In fact, since the beginning of the twenty-first century, certain countries have been including provisions and even chapters on electronic commerce, as well as rules on data flows, in preferential trade agreements (PTAs). It is well known that the United States has been important in the creation and diffusion of digital trade rules, especially after the 2002 US Digital Trade Agenda and the Bipartisan Trade Promotion Authority Act of the same year.Footnote 6 Not so well known is the relevant role other actors have played in the development of these rules.Footnote 7 This contribution focuses on one group of countries of the Latin American region, which have been the most important vectors of the inclusion of e-commerce and data rules in PTAs – a group that includes Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Panama. For the purpose of this chapter, we consider ‘Latin American’ PTAs those trade agreements in which at least one, or more parties, is a country from Latin America and the Caribbean region.

Besides highlighting the contribution that those countries have had in the creation and diffusion of this new rule-making, our goal is also to determine the level of regulatory convergence that Latin American countries (LACs) have on rules on digital trade and data flows. For this purpose, we understand regulatory convergence as an overarching notion that aims to reduce unnecessary regulatory incompatibilities between countries in a dynamic and incomplete process.Footnote 8 The rationale behind regulatory convergence in PTAs stems from the idea that regulatory diversity may entail significant costs that can hinder cross-border exchanges,Footnote 9 and that the maintenance of needlessly burdensome cross-border differences in regulation can result in a number of additional negative policy impacts, including higher transaction costs stemming from information asymmetries.Footnote 10 Divergent regulatory requirements can lead to duplication of procedures and costs in trade that are important for all internationally active businesses and especially so for small- or medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), for which such fixed costs can be a deciding factor in whether or not to export or invest, including across borders.Footnote 11 Lack of transparency or clarity of regulations, as well as excessive, inefficient, or ineffective regulations, create unnecessary delays or impose costs on traders and investors.Footnote 12

Regulatory convergence mechanisms include substantive or procedural aspects that are aimed at two different types of regulatory outcomes. In some agreements, regulatory convergence aims to achieve substantive regulatory harmonisation (similar or equivalent regulation – ‘substantive convergence’). Other agreements consider harmonisation of the processes by which regulations are developed, adopted, publicised, and implemented (similar or equivalent procedures – ‘procedural convergence’). With different denominations,Footnote 13 both approaches are present in the PTAs examined in this chapter.

The chapter is organised as follows. After the introduction, we provide a detailed description of e-commerce and data rules found in Latin American PTAs, and their convergence or divergence. Then we briefly present the domestic frameworks of relevant LACs on digital trade–related topics, as well as their consistency with existing international commitments, with special emphasis on personal data protection. To conclude, we highlight some potential conflicts that could arise between these countries’ domestic regulations and international commitments in the field.

B Regulatory Convergence in E-Commerce and Data Flow Provisions in Latin American PTAs

The inclusion of provisions in PTAs referring explicitly to e-commerce and data flows is not a recent phenomenon, although it has evolved importantly in the past two decades. According to the TAPED dataset, 191 PTAs include provisions that are related to e-commerce and data flows, with 116 PTAs with e-commerce provisions and 86 with e-commerce chapters.Footnote 14 These provisions are highly heterogeneous and address various issues including customs duties and non-discriminatory treatment of digital products, electronic signatures, paperless trading, unsolicited electronic messages, as well as consumer protection, data protection, data flows, and data localisation.

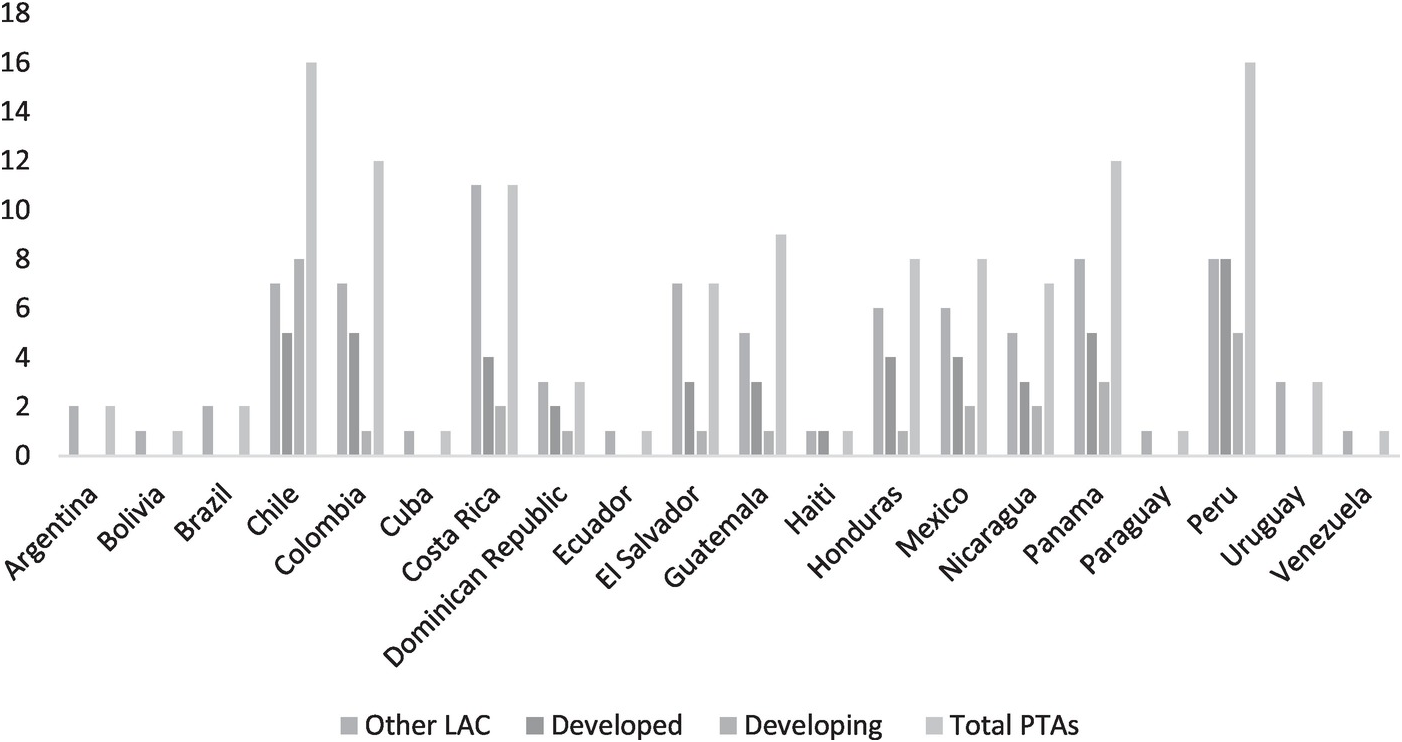

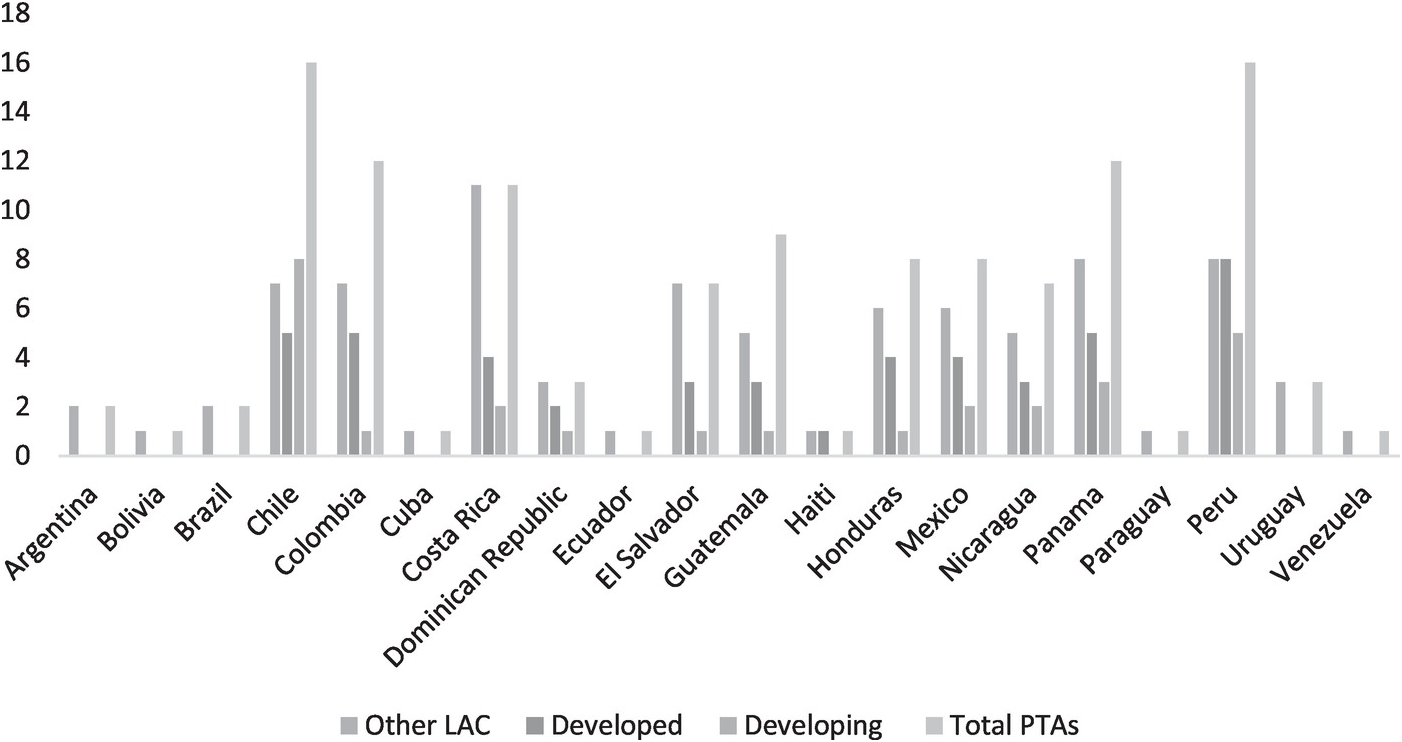

As detailed in Table 13.1, of the total number of PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions the countries of Latin America have concluded 53 per cent (62 agreements, 47 chapters). Twenty-nine of these agreements have been concluded with developed countries (47 per cent of this subset) and 33 with other developing countries (53 per cent of this subset), most of them also from Latin America (26 agreements in total). The countries leading this treaty-making practice in the region are Chile (18 PTAs) Peru (16 PTAs), Colombia (12 PTAs), Panama and Costa Rica (11 PTAs each). This is in line with the fact that the surge of PTAs having e-commerce provisions involves both developed and developing countries. 49 per cent of the PTAs with e-commerce provisions were negotiated between developed and developing countries, and 47 per cent were negotiated between developing countries.Footnote 15

Table 13.1. Latin American PTAs with e-commerce or data flow provisions

| Country | Other LACs | Developed | Developing | Total PTAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Bolivia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Brazil | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Chile | 7 | 5 | 8 | 16 |

| Colombia | 7 | 5 | 1 | 12 |

| Cuba | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Costa Rica | 11 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| Dominican Republic | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Ecuador | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| El Salvador | 7 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| Guatemala | 5 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| Haiti | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Honduras | 6 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| Mexico | 6 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| Nicaragua | 5 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Panama | 8 | 5 | 3 | 12 |

| Paraguay | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Peru | 8 | 8 | 5 | 16 |

| Uruguay | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Venezuela | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

The earliest e-commerce provision in a PTA involving a Latin American country is found in the 2001 Canada–Costa Rica Free Trade Agreement (FTA), which included a Joint Statement on Global Electronic Commerce. In a non-binding fashion, it addresses several issues, like the applicability of WTO rules to e-commerce, supporting industry developments in the field, stakeholder’s participation, transparency, and consumer and data protection. In 2002, the Chile–EU Association Agreement properly included e-commerce provisions in the text of the treaty on issues such as cooperation and data protection.Footnote 16 The first PTA concluded in the region having a dedicated e-commerce chapter is the 2002 Chile–US FTA. In 2006, the Nicaragua–Taiwan FTA began the inclusion of provisions on data flows as part of its cooperation commitments. The number of Latin American PTAs with such provisions has increased over the years (see Figure 13.1), simultaneously with the growing discussions on the digital economy and its move up as a topic on the policy agendas and negotiation tables.

Figure 13.1. Latin American PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions

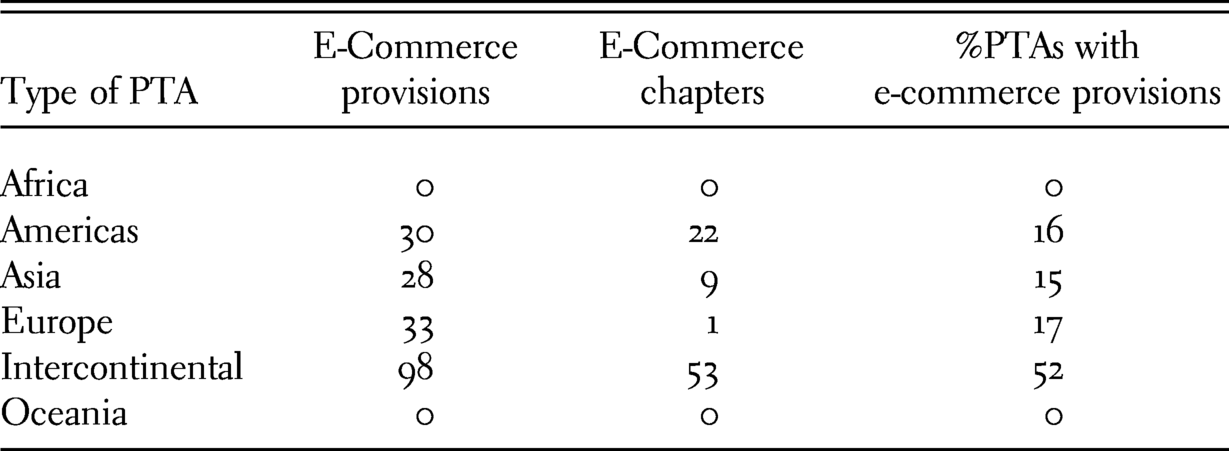

Although the number of PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions remains limited, the last eight years have shown a significant increase in the number of agreements with such provisions. Overall, agreements including such provisions are mainly of an intercontinental nature, but around one-third of these PTAs have at least one Latin American country as a contracting party (thirty-one treaties) and Latin America is one of the most relevant regional area with this type of treaty-making (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2. PTAs concluded with e-commerce provisions per region

| Type of PTA | E-Commerce provisions | E-Commerce chapters | %PTAs with e-commerce provisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Americas | 30 | 22 | 16 |

| Asia | 28 | 9 | 15 |

| Europe | 33 | 1 | 17 |

| Intercontinental | 98 | 53 | 52 |

| Oceania | 0 | 0 | 0 |

PTAs with e-commerce provisions involving LACs have also increased their level of detail significantly over the years. Seven is the average number of PTA provisions found on e-commerce chapters in the past five years, with an average of 955 words. A treaty involving a Latin American country, the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), is currently the PTA in force with the largest number of articles and words on e-commerce, as its current text has 19 articles and an average of 3,206 words. Several PTAs having a Latin American country as a party have devoted more than 11 articles and 1,900 words to these topics, like the 2017 Argentina–Chile FTA, the 2015 Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol (PAAP), the 2016 Chile–Uruguay FTA, the 2018 Australia–Peru FTA, the 2018 Brazil–Chile FTA, and both the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), whose e-commerce chapter reiterates verbatim the TPP text.

C E-Commerce and Data Provisions in Latin American PTAs

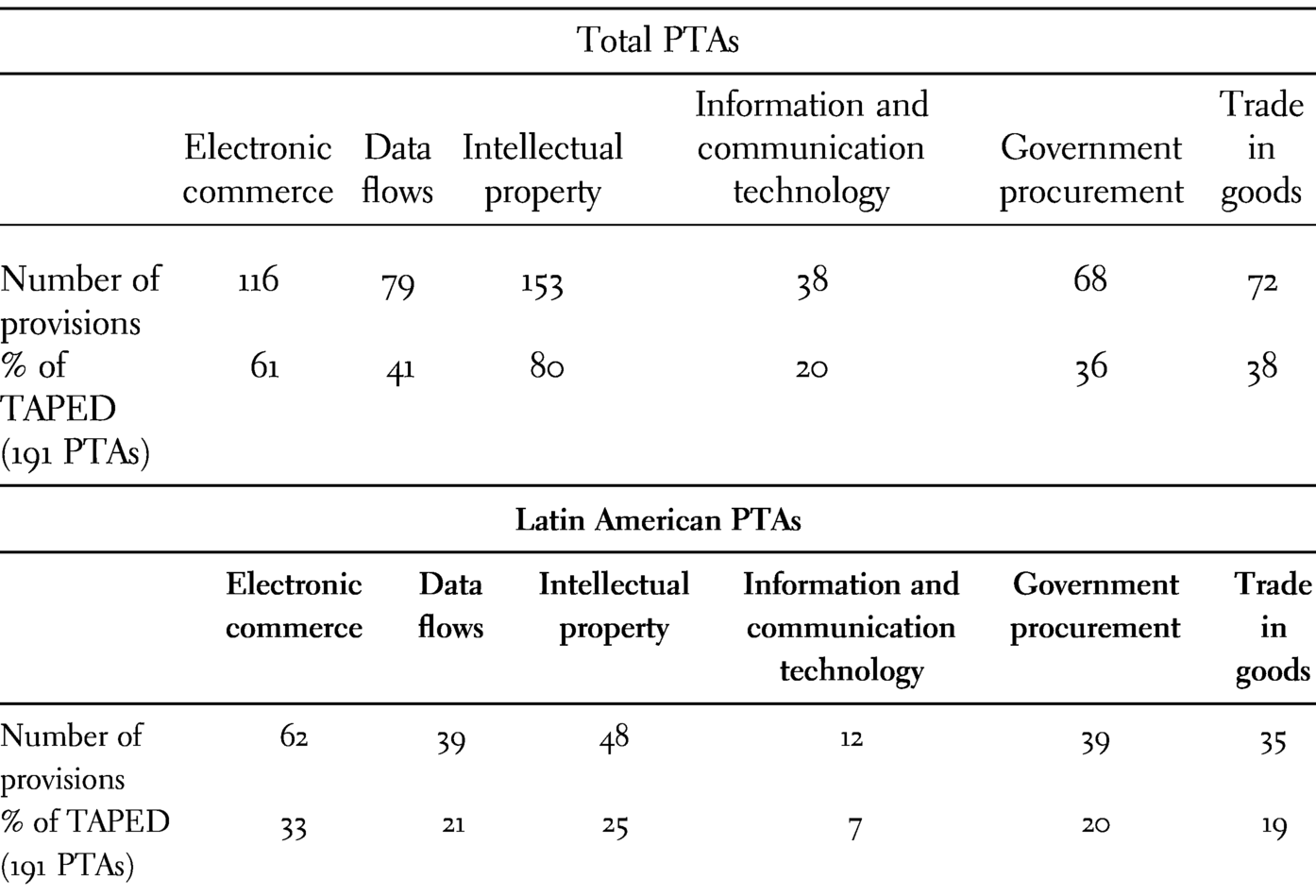

E-commerce and data provisions are found in the main text of several Latin American PTAs, mostly on chapters or sections dedicated to e-commerce or intellectual property (IP). When available, data flow provisions are also found in these chapters or sections, but are commonly included in chapters on specific services, mainly telecommunication and financial services. E-commerce provisions can also be found in side documents, like annexes, joint statements, and side letters. As presented in Table 13.3, Latin American PTAs represent an important number of treaties with such provisions.

Table 13.3. Total PTAs and Latin American PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions

| Total PTAs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic commerce | Data flows | Intellectual property | Information and communication technology | Government procurement | Trade in goods | |

| Number of provisions | 116 | 79 | 153 | 38 | 68 | 72 |

| % of TAPED (191 PTAs) | 61 | 41 | 80 | 20 | 36 | 38 |

| Latin American PTAs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic commerce | Data flows | Intellectual property | Information and communication technology | Government procurement | Trade in goods | |

| Number of provisions | 62 | 39 | 48 | 12 | 39 | 35 |

| % of TAPED (191 PTAs) | 33 | 21 | 25 | 7 | 20 | 19 |

In the following sections, we examine the provisions of Latin American PTAs in two main groups: (i) electronic commerce and (ii) cross-border data flows.

An assessment of the extent of legalisation of these provisions was also performed, distinguishing between ‘soft’, ‘mixed’, and ‘hard’ commitments. We considered as ‘soft’ those commitments that are not enforceable by the parties, like ‘best efforts’ and cooperation commitments. We classified as ‘hard’ those commitments that oblige a party to comply with a rule or a principle and which are enforceable by another party. Finally, we consider an agreement with ‘mixed’ legalisation if the treaty has both soft and hard commitments. Similarly, we included in this category references to other agreements that are only partially applicable.Footnote 17

I Electronic Commerce

1 Objectives and Principles

Several Latin American PTAs with e-commerce chapters converge on explicitly stating a number of objectives like avoiding unnecessary barriers to e-commerce (37 PTAs), addressing the needs of SMEs (31 PTAs), promoting and facilitating its use (both between the parties and globally (30 PTAs), considering private participation in the development of the regulatory framework for e-commerce (15 PTAs), and the principle of technological neutrality (15 PTAs).Footnote 18 The first three objectives and principles are also commonly found in PTAs with e-commerce chapters concluded by countries outside of Latin America.

2 Applicability of WTO Rules

Although all Latin American countries that have concluded PTAs with e-commerce or data flow provisions are members of the WTO that does not necessarily mean that these countries consider that WTO law applies to digital trade. In fact, only one-third of Latin American PTAs include provisions on the applicability of WTO rules to e-commerce – twenty agreements from a total of sixty-two PTAs – with important differences of language across agreements. The first treaty including such provisions is the 2001 Canada–Costa Rica FTA, which only makes a reference to the maintenance of the WTO practice of not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions between the parties.Footnote 19 Some treaties explicitly recognise the applicability of the WTO rules to electronic commerce, but without clearly specifying which the applicable provisions would be.Footnote 20 Certain agreements clarify the application of WTO rules to e-commerce ‘to the extent they affect electronic commerce’,Footnote 21 or to measures ‘affecting electronic commerce’.Footnote 22 In other softer variations, countries merely reaffirm their respective commitments under WTO agreements in the respective e-commerce chapter/section.Footnote 23

3 National Treatment (NT) and Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) Obligations

The number of Latin American agreements including provisions with explicit commitments on non-discrimination on digital trade is relatively small. In the TAPED dataset, eighteen PTAs include MFN commitments to give a treatment no less favourable on e-commerce to parties to the treaty than they accord to non-parties; and nineteen PTAs consider NT commitments to give a treatment no less favourable to other parties to the treaty than they accord domestically on e-commerce. In contrast, in the whole TAPED dataset we find thirty-five PTAs with NT and thirty-two with MFN provisions.

The large majority of these provisions are binding.Footnote 24 Following the 2015 Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol (PAAP), some agreements consider NT and MFN together, as part of a general commitment to non-discriminatory treatment of digital products. According to this provision, no party shall accord less favourable treatment to digital products created, produced, published, contracted for, commissioned or first made available on commercial terms in the territory of another party or to digital products of which the author, performer, producer, developer, or owner is a person of another party than it accords to other like digital products.Footnote 25 In certain treaties, a footnote further clarifies that to the extent that a digital product of a non-party is a ‘like digital product’, it will qualify as an ‘other like digital product’.Footnote 26

But the majority of Latin American PTAs consider separate paragraphs for NT and MFN. On national treatment, the most common wording goes back to the 2006 Panama–Singapore FTA, which stipulates that a party

shall not accord less favourable treatment to some digital products than it accords to other like digital products, on the basis that the digital products receiving less favourable treatment are created, produced, published, stored, transmitted, contracted for, commissioned or first made available on commercial terms outside its territory; or the author, performer, producer, developer or distributor is a person of another Party or a non-Party; or so as otherwise to afford protection to other like digital products that are created, produced, published, stored, transmitted, contracted for, commissioned, or first made available on commercial terms in its territory.Footnote 27

A variation of this provision uses ‘may’ instead of ‘shall’, theoretically making the commitment less binding.Footnote 28 Another variation narrows the NT as it only applies to the digitally delivered products associated with the territory of the other party or where the author, performer, producer, developer, or distributor is a person of the other party.Footnote 29 A simpler recognition of NT is found in the Canada–Peru FTA, where the parties merely confirm the application of national treatment for goods to trade conducted by electronic means.Footnote 30

Regarding MFN, some agreements stipulate that a party

shall not accord less favourable treatment to digital products created, produced, published, stored, transmitted, contracted for, commissioned or first made commercially available in the territory of another Party, than it accords to like digital products in the territory of a non-Party. Furthermore, a Party shall not accord less favourable treatment to digital products of which the author, performer, producer, developer or distributor is a person of a non-Party.Footnote 31

A variation of this provision uses ‘may’ instead of ‘shall’, making the commitment less binding.Footnote 32

4 Customs Duties

One of the most common provisions found in PTAs regarding digital trade (eighty-four PTAs in TAPED) is the commitment to not impose customs duties on digital products. Wu points out that this type of provision facilitates commerce in downloadable products, such as software, e-books, music, movies, and other digital media.Footnote 33 Despite being commonplace, these commitments have different wording in how the obligation is drafted. From the thirty-nine Latin American PTAs that include such provision, some agreements merely reaffirm the WTO member’s practice of not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions,Footnote 34 rather than seeking to expand it towards a WTO-plus obligation. However, the most common approach is a provision including a permanent moratorium on duty-free treatment in the PTA, meaning that no customs duties should be imposed on electronic transmissions and digital products. Yet again, this second type of provision has several variations.

Some agreements plainly stipulate that a party may not apply customs duties on digital products of the other party,Footnote 35 or in more binding terms that it ‘shall not’ impose customs duties on electronic transmissions,Footnote 36 or not apply customs duties, fees, or charges on import or export by electronic means of digital products.Footnote 37 In certain agreements, the parties agree that electronic transmissions shall be considered as the provision of services, which cannot be subject to customs duties.Footnote 38 In other treaties, the parties simply agree not to impose duties on ‘deliveries by electronic means’.Footnote 39

Only a couple of agreements consider this obligation regardless whether the digital products in question are fixed on a carrier medium or transmitted electronically.Footnote 40 In several of these treaties there is an explicit distinction between digital products which are transmitted by electronic means and those whose sale occurs online but who are physically transported over the border. According to these PTAs a party shall not apply customs duties on digital products by electronic transmission, but when these are transmitted physically, the customs value is only limited to the value of the carrier medium and does not include the value of the digital product stored on the carrier medium.Footnote 41 A variation of this provision, usually found in agreements concluded with the United States, uses ‘may’ instead of ‘shall’, theoretically making the commitment less binding.Footnote 42 Certain Latin American PTAs explicitly mention that the moratorium does not extend to internal taxes or other charges. The wording of this exclusion varies across treaties. While some do not prevent a party from imposing an internal tax or charge to digital products delivered or transmitted electronically,Footnote 43 others exclude products imported/exported by electronic transmissions or means,Footnote 44 or content transmitted electronically between a person of one party and a person of the other party.Footnote 45

5 Electronic Authentication

Thirty-seven Latin American PTAs include provisions on electronic authentication, which represent around half of the overall universe of PTAs having these provisions. Typically, they allow authentication technologies and mutual recognition of digital certificates and signatures. While earlier treaties included only best efforts commitments in this field, recent agreements include more binding and mandatory clauses. Fifty per cent of all PTAs including such provisions have been concluded by Latin American countries.

We find the earliest example of soft commitments on electronic authentication back in 2001, when Canada and Costa Rica merely acknowledged the necessity of policies to facilitate the use of technologies for authentication and for the conduct of secure e-commerce.Footnote 46 Other agreements included only cooperation commitments on electronic authentication. These comprise activities to share information and experiences on laws, regulations, and programmes on electronic signaturesFootnote 47 or secure electronic authentication;Footnote 48 and to ‘maintain a dialogue’ on the facilitation of cross-border certification services,Footnote 49 or digital accreditation.Footnote 50

More binding commitments on authentication and digital certificates establish restrictions on legislation, using both negative and positive obligations. According to a first group of agreements, no party may adopt or maintain legislation that (i) prevents or prohibits parties from having the opportunity to prove in court that their electronic transaction complies with any legal requirements with respect to authentication;Footnote 51 or (ii) prohibits parties to an electronic transaction from mutually determining the appropriate authentication methods.Footnote 52 Some of these treaties consider this obligation in more binding terms (‘no Party shall adopt or maintain’).Footnote 53 In a second group of agreements, each party has the positive obligation (‘each Party shall adopt or maintain’) of having domestic legislation for electronic authentication that permits parties to electronic transactions to (i) determine the appropriate authentication technologies and implementation models for their electronic transactions, without limiting the recognition of such technologies and implementation models; and (ii) to have the opportunity to prove in court that their electronic transactions comply with any legal requirements.Footnote 54

Further commitments on electronic signatures establish that neither party may deny the legal validity of a signature solely on the basis that it is in electronic form, either in negative (‘may not maintain’)Footnote 55 or positive terms (‘a Party shall not deny’).Footnote 56 Some agreements include exceptions to these commitments, considering that a party may require that the electronic signatures be certified by an authority or a supplier of certification services accredited under the party’s law or regulations for a particular category of transactions or communications.Footnote 57 In certain cases, it is stipulated that such requirements shall be objective, transparent, and non-discriminatory and relate only to the specific characteristics of the category of transactions concerned.Footnote 58 In other agreements, it is considered that a party may deny the legal validity of an electronic signature under circumstances provided for in its law.Footnote 59