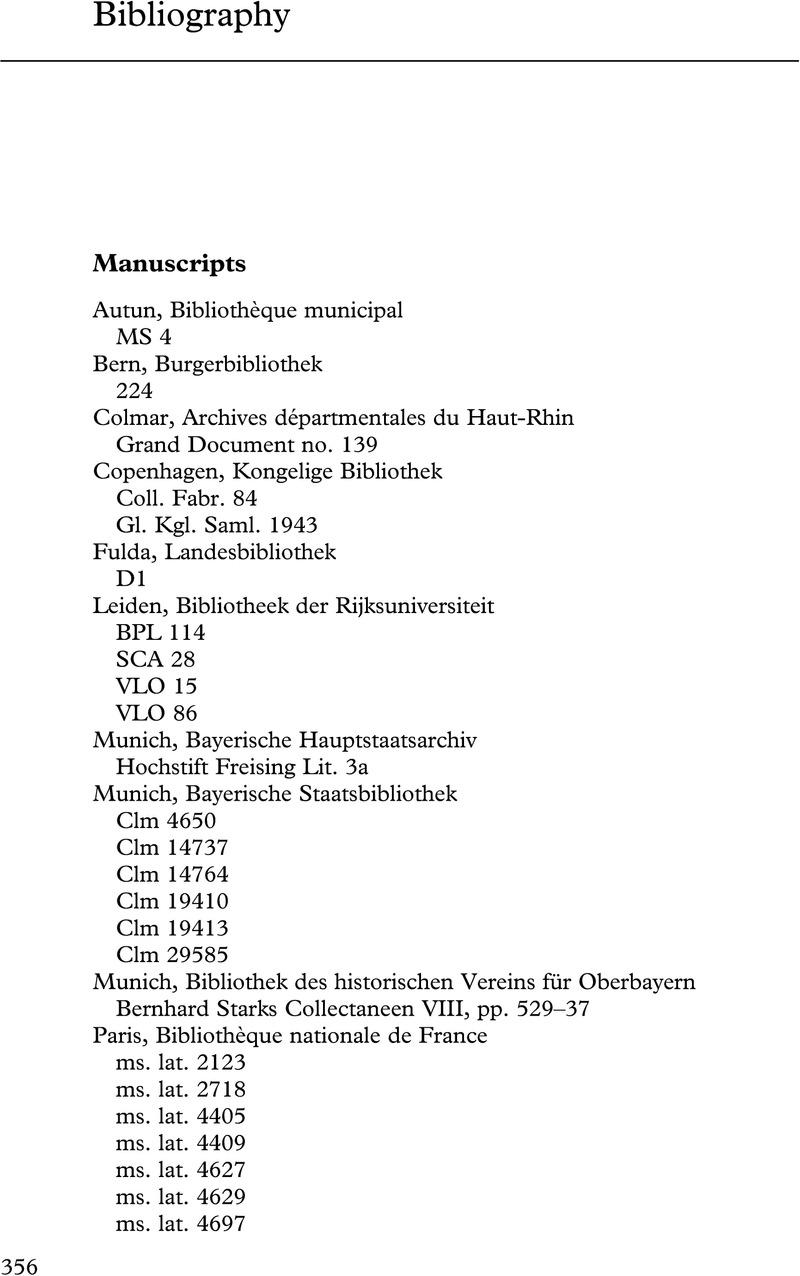

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 December 2022

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Beyond the Monastery WallsLay Men and Women in Early Medieval Legal Formularies, pp. 356 - 376Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022