Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Glossary

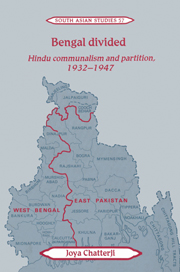

- Map 1 Bengal districts

- Introduction

- 1 Bengal politics and the Communal Award

- 2 The emergence of the mofussil in Bengal politics

- 3 The reorientation of the Bengal Congress, 1937–45

- 4 The construction of bhadralok communal identity: culture and communalism in Bengal

- 5 Hindu unity and Muslim tyranny: aspects of Hindu bhadralok politics, 1936–47

- 6 The second partition of Bengal, 1945–47

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge South Asian Studies

1 - Bengal politics and the Communal Award

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 August 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Glossary

- Map 1 Bengal districts

- Introduction

- 1 Bengal politics and the Communal Award

- 2 The emergence of the mofussil in Bengal politics

- 3 The reorientation of the Bengal Congress, 1937–45

- 4 The construction of bhadralok communal identity: culture and communalism in Bengal

- 5 Hindu unity and Muslim tyranny: aspects of Hindu bhadralok politics, 1936–47

- 6 The second partition of Bengal, 1945–47

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge South Asian Studies

Summary

By 1929, British policy-makers in London and New Delhi could see that the constitutional arrangements devised by Montagu and Chelmsford ten years before would have to be reviewed. The pressures of the past decade had brought constitutional change back upon the political agenda. ‘Provincial autonomy’ was devised as a measure to fend off pressure at the centre by nationalist politicians, while at the same time broadening the base of Indian collaboration with the Raj. While ‘devolving’ some power to Indians, the reforms restructured British control over India by a strategic retreat to the centre, where the Raj continued to hold on to the levers of power. At the same time, a number of safeguards were designed to limit the scope of the greater ‘autonomy’ which was being offered to the provinces. The Communal Award of 1932 was an integral part of this strategy.

The Communal Award was the result of London's decision to divide power in the provinces among the rival communities and social groups which, in its view, constituted Indian society. British administrators saw India as ‘essentially a congeries of widely separated classes, races and communities with divergences of interests and hereditary sentiment which for ages have precluded common action or local unanimity’. In fact, the categories into which the administrators classified Indian society reflected British assumptions rather more closely than the social realities of the sub-continent.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Bengal DividedHindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947, pp. 18 - 54Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1994