Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Note on the Presentation of Auchinleck Texts

- Introduction The Auchinleck Manuscript: New Perspectives

- 1 The Auchinleck Manuscript Forty Years On

- 2 Codicology and Translation in the Early Sections of the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 3 The Auchinleck Adam and Eve: An Exemplary Family Story

- 4 A Failure to Communicate: Multilingualism in the Prologue to Of Arthour and of Merlin

- 5 Scribe 3’s Literary Project: Pedagogies of Reading in Auchinleck’s Booklet 3

- 6 Absent Presence: Auchinleck and Kyng Alisaunder

- 7 Sir Tristrem, a Few Fragments, and the Northern Identity of the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 8 The Invention of King Richard

- 9 Auchinleck and Chaucer

- 10 Endings in the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 11 Paraphs, Piecework, and Presentation: The Production Methods of Auchinleck Revisited

- 12 Scribal Corrections in the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 13 Auchinleck ‘Scribe 6’ and Some Corollary Issues

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts Cited

- General Index

- Manuscript Culture in the British Isles

8 - The Invention of King Richard

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Note on the Presentation of Auchinleck Texts

- Introduction The Auchinleck Manuscript: New Perspectives

- 1 The Auchinleck Manuscript Forty Years On

- 2 Codicology and Translation in the Early Sections of the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 3 The Auchinleck Adam and Eve: An Exemplary Family Story

- 4 A Failure to Communicate: Multilingualism in the Prologue to Of Arthour and of Merlin

- 5 Scribe 3’s Literary Project: Pedagogies of Reading in Auchinleck’s Booklet 3

- 6 Absent Presence: Auchinleck and Kyng Alisaunder

- 7 Sir Tristrem, a Few Fragments, and the Northern Identity of the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 8 The Invention of King Richard

- 9 Auchinleck and Chaucer

- 10 Endings in the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 11 Paraphs, Piecework, and Presentation: The Production Methods of Auchinleck Revisited

- 12 Scribal Corrections in the Auchinleck Manuscript

- 13 Auchinleck ‘Scribe 6’ and Some Corollary Issues

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts Cited

- General Index

- Manuscript Culture in the British Isles

Summary

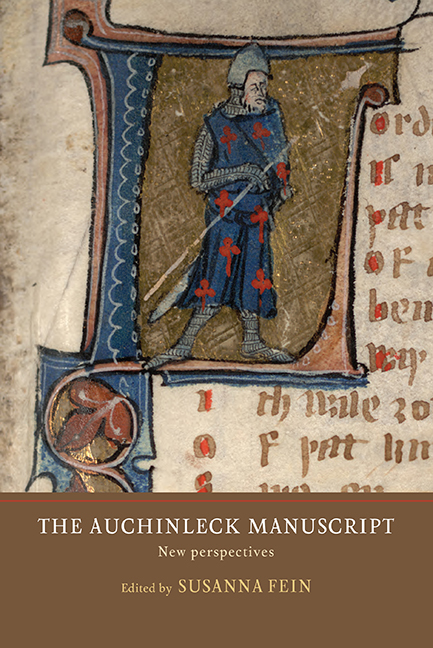

ON those rare occasions when we talk or write about the text we have come to refer to as Richard Coer de Lion, the Middle English romance depicting England's late-twelfth-century crusader-king Richard I, we often begin with particular details about it to pique the interests and jog the memories of our listeners or readers. First, Richard's mother is an Eastern princess and perhaps a fairy, who, when made to watch the Eucharist's elevation, shoots up through the church roof, never to be heard from again. Next, Richard twice cannibalizes Saracens while on crusade, once with plausible deniability and the second time with full knowledge. And, finally, the earliest extant copy of the romance survives in the Auchinleck manuscript (Edinburgh, NLS, MS Advocates 19. 2. 1), a book probably produced in London between 1331 and 1340, and known today for its large number of the earliest or only copies of texts that significantly comprise our corpus of Middle English romance (a seemingly cold, hard, scholarly fact self-consciously deployed amid the sensationalism).

Beyond the many, many obvious problems to which fairy mothers and cannibalism give rise, this ‘common knowledge’ that has come to at once emblematize, advertise, and contextualize Richard Coer de Lion presents an additional difficulty, made more acute when one sits down to write about the earliest extant copy of the romance: none of these things we think we know about Richard Coer de Lion are true of its inscription in the Auchinleck manuscript. Rather, Auchinleck's Richard Coer de Lion – or King Richard as it is titled in the manuscript and as I will refer to it here – makes no mention of a fairy mother, beginning instead with a Prologue, the fall of Jerusalem, and Richard's preparations for sea travel to Acre. It does not now and probably never did contain scenes of cannibalism. And it is only partially preserved in the Auchinleck manuscript proper. Of the little more than a thousand lines of King Richard that survive, roughly seven hundred occur as almost-consecutive fragments that were recovered, remarkably, in various eighteenth-century Scottish notebooks and bindings, now held in multiple libraries.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Auchinleck Manuscript: New Perspectives , pp. 127 - 138Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2016

- 2

- Cited by