Book contents

- After Darwin

- After Series

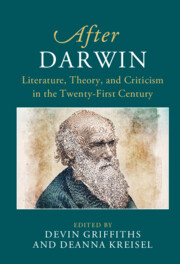

- After Darwin

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Part I Environments after Darwin

- Part II Differences after Darwin

- Chapter 6 Disability after Darwin

- Chapter 7 Race after Darwin

- Chapter 8 Darwin under Domestication

- Chapter 9 Feminism at War

- Chapter 10 The Survival of the Unfit

- Part III Humanism after Darwin

- References

- Index

Chapter 9 - Feminism at War

Sexual Selection, Darwinism, and Fin-de-Siècle Fiction

from Part II - Differences after Darwin

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 December 2022

- After Darwin

- After Series

- After Darwin

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Part I Environments after Darwin

- Part II Differences after Darwin

- Chapter 6 Disability after Darwin

- Chapter 7 Race after Darwin

- Chapter 8 Darwin under Domestication

- Chapter 9 Feminism at War

- Chapter 10 The Survival of the Unfit

- Part III Humanism after Darwin

- References

- Index

Summary

Tumultuous nineteenth-century political debates, fears of violent revolutions, and the rise of women’s rights campaigns in Britain, the United States, and France provide a context for considering Darwin’s theory of sexual selection and its engagement with feminism. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) identified sexual differences, male–male combat, and female choice in courtship as key elements of animal copulation, while insisting that male choice controls human sexual relations, ideas that inspired radically different reactions from feminists, who objected to what they regarded as Darwin’s sexism, and fiction writers, who highlighted women characters resisting patriarchal expectations and making independent decisions. The long history and profound consequences of the concepts of sexual difference and sexual selection call for careful consideration of the intertwining of Darwin’s scientific theories about sexual difference and choice with divergent cultural formations, ranging from social Darwinism to feminist theory, and propose a more fluid understanding of sex and gender that supersedes the earlier two-sex model.

Keywords

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- After DarwinLiterature, Theory, and Criticism in the Twenty-First Century, pp. 108 - 120Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022