10 results

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Embodied Experience in British and French Literature, 1778–1814

- Published online:

- 19 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 250-254

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Embodied Experience in British and French Literature, 1778–1814

- Women and Belonging

-

- Published online:

- 19 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Concluding Thoughts

-

- Book:

- Minoan Zoomorphic Culture

- Published online:

- 17 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 372-379

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

One - Life among the Animalian in Bronze Age Crete and the Southern Aegean

-

- Book:

- Minoan Zoomorphic Culture

- Published online:

- 17 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 1-37

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Thinking with Things

- from Part I - Historical Materialism and the Materials of History

-

- Book:

- Poetry and the Limits of Modernity in Depression America

- Published online:

- 21 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 October 2023, pp 25-44

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 16 - “The Man That Was a Thing”

- from Part V - Envisioning Race

-

-

- Book:

- Race in American Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 26 May 2022

- Print publication:

- 16 June 2022, pp 262-275

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - The Blood of Christ and the Christology of Things

- from Part IV - The Blood of God at the Heart of Things

-

- Book:

- Blood Theology

- Published online:

- 22 March 2021

- Print publication:

- 25 March 2021, pp 201-216

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - The Inorganic

- from Part II - New Objects of Enquiry

-

-

- Book:

- After the Human

- Published online:

- 26 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 10 December 2020, pp 147-158

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Object Studies and Keepsakes, Artifacts, and Ephemera

- from Part I - The Textual Hemingway

-

-

- Book:

- The New Hemingway Studies

- Published online:

- 30 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 September 2020, pp 63-79

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

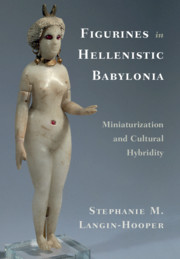

Figurines in Hellenistic Babylonia

- Miniaturization and Cultural Hybridity

-

- Published online:

- 19 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2020