Government surveys indicate that 1 in 11 people in the UK report debt or arrears. However, among individuals with mental health problems this figure rises to 1 in 4, and to 1 in 3 among people with psychotic conditions (Office for National Statistics, 2002a ). When applied to the national recommended case-load for community mental health nurses of 35 patients (Department of Health, 2002), these figures suggest that between 9 and 12 of these patients might be living with debt or arrears.

Clearly, when it can be repaid or managed, debt is not inherently problematic. Furthermore, many individuals with mental health problems have the skills and capacity to manage their finances. However, concerns have been voiced by professionals and carers about the negative impact that debt problems can have on patients’ mental health, about mental health problems acting as pathways into debt and about irresponsible practice experienced by people with mental health problems from an expanding UK financial services industry (Reference EdwardsEdwards, 2003). These concerns have been framed within a wider debate on UK personal debt, which now totals £1.25 trillion (Credit Action, 2006).

Despite this, patient debt is rarely discussed in the psychiatric literature. This may reflect a belief that ‘debt’ is better addressed by social workers and nursing staff. However, although psychiatrists should not be expected to become proxy ‘debt advisors’, they do arguably have a role to play in:

-

• knowing how to respond when patients report a ‘debt crisis’

-

• proactively looking for signs that individuals could be at risk of debt (crisis prevention)

-

• raising and discussing debt with patients (including during routine assessments)

-

• effectively referring individuals for specialist debt counselling (and monitoring progress)

-

• assessing whether patients have sufficient mental capacity to manage their finances

-

• assigning control of finances to external sources (appointees and attorneys).

Research suggests, however, that health professionals are not engaging with patient debt because they feel insufficiently knowledgeable and confident (Reference Sharpe and BostockSharpe & Bostock, 2002). This could mean that a debt crisis is not identified or managed, that mental health could be subsequently worsened and that an even larger set of future problems may build up for the individual, their carers and the professionals supporting them.

In this article we therefore aim to improve psychiatrists’ knowledge and confidence in dealing with patients’ debt. Throughout we provide recommendations on the practical actions that psychiatrists can take to avert patient debt crises. These are described in more detail in the leaflet Final Demand: Debt and Mental Health (Reference FitchFitch, 2006a ). An outline of the terminology we use appears in Box 1.

Box 1 Debt analysis and terminology

Debt

Debt is defined as having outstanding money to repay. Someone is therefore ‘in debt’ if they have a personal bank loan, owe money on credit cards, have a mortgage, or are unable to settle a domestic or utility bill.

Problem debt

If people fall behind with payments, bills or other commitments they have a problem debt. There is no monetary point at which ‘debt’ becomes ‘problem debt’. The UK organisation Citizens Advice has suggested that the transition into problem debt may occur when the individual is unable to meet repayment and other commitments without reducing other expenditure below normal minimum levels. Others have suggested that falling behind on a third month of payments might indicate the emergence of a problem debt.

Problem debt can also be understood as a process – understanding the steps and mechanisms through which a manageable debt becomes a problem debt can help professionals act before a full-blown crisis occurs.

Priority debts

These are debts with the most serious consequences for non-payment, such as the loss of an essential service (e.g. disconnection of domestic utilities) or court action that could lead to the loss of liberty. Priority debts need to be paid back before all other debts.

What is debt?

The popular media have constructed debt as a problem of epidemic proportions. Headlines proclaim Britain as a ‘nation up to its eyeballs in debt’ (BBC, 2003), and editorials attack the ‘feckless borrowers’, ‘reckless lenders’ and the ‘see-it-want-it-have-it culture’ responsible for this.

This viewpoint is not, however, shared by financial organisations, which make an important distinction between ‘debt’ and ‘problem debt’. First, they observe that most credit use is non-problematic: government surveys indicate that 95% of UK adults – the same proportion as a decade ago – say that their debt is not a ‘heavy burden’ (Department for Trade and Industry, 2005). Second, they note that the proportion of those with problem debt is minor: in the same surveys only 4% of adults report outstanding consumer debts or domestic arrears of more than 3 months. Third, they contend that the benefits of debt – access to cash when needed, the convenience of credit cards and a means of spreading expenditure over time – outweigh any disadvantages.

Social commentators are more sceptical. They observe that problem debt is socially patterned, affecting some social groups more than others. First, they note that, although government surveys indicate that only 4% of UK respondents report outstanding debts or arrears, this rises to 64% among people with annual incomes lower than £9500 (Department for Trade and Industry, 2005). Second, among those in debt, there is an overrepresentation of individuals experiencing ‘significant life events’ in the past year, disabled people and their carers (Department for Trade and Industry, 2004) and people with mental health problems (Office for National Statistics, 2002a ). Third, these groups are also more likely to have arrears on ‘priority debts’ (such as domestic bills), which have the most severe legal consequences. They may also borrow from high-cost home credit or door-step lenders, with annual percentage rates (APRs) ranging from 100% to 400% or more (Reference Collard and KempsonCollard & Kempson, 2005). As with other forms of inequality, problem debt may therefore affect the most vulnerable.

Health analysts also contend that debt has a meaning for individual health and social well-being, as well as for financial status. Reflecting established literature on poverty as a determinant and consequence of poor physical and mental health (for a review see Reference Murali and OyebodeMurali & Oyebode, 2004), analysts point to a similar relationship between debt and health. Furthermore, it has been argued that debt may be a factor in social isolation, feelings of insecurity and shame, self-harm and suicidal ideation. Debt can therefore be understood in financial, health and social terms.

What is the extent of debt?

The most robust evidence comes from a large UK government survey undertaken in 2000 (Office for National Statistics, 2002a ). This found that 9% of people without mental health problems reported debt or arrears, whereas 24% of individuals with neurotic conditions and 33% of those with psychotic conditions were in debt. The survey found that a higher proportion of individuals with mental health problems reported debt on every single indicator than those without. The most common arrears among respondents with mental health problems were priority debts such as domestic bills, rent and local authority taxes, although consumer debts were also cited. People with mental health problems were four to five times more likely to have had a domestic utility disconnected than those without such problems – 3% of people without mental health problems, 11% of those with neurotic conditions and 14% of those with psychosis.

A handful of studies have also been undertaken on the prevalence of debt among people who self-harm. Reference HatcherHatcher (1994), for example, found that 37% of 147 patients assessed after an act of self-poisoning were in debt. Critically, more than three-quarters of those in debt had not sought help. Reference TaylorTaylor (1994) undertook a comparative study of the finances of 53 accident and emergency patients who had harmed themselves and those of 53 patients from a fracture clinic. Almost three times as many in the self-harm sample reported ‘significant worries with debt that you cannot repay’ than in the control group (37 v. 13%). Only a quarter of those with debts had sought help or advice. Finally, surveys conducted with service users and specialist advice agencies provide insight into debt among people with mental health problems. In a review of this literature, Reference DavisDavis (2003) reports that a third or more of those surveyed had debt problems.

What impact can debt have?

Research studies are often unable to establish whether debt is a determinant or consequence of mental health problems. However, research indicates that debt is associated with the following factors.

Anxiety and stress

Reference Drentea and LavrakasDrentea & Lavrakas (2000) found that among 1000 US survey participants, self-reported anxiety increased with the ratio of credit card debt to personal income. Reference Nettleton and BurrowsNettleton & Burrows (1998), using British Household Panel Survey data, report that the onset of mortgage debt had a negative impact on mental health and, among male participants, resulted in increased rates of general practitioner (GP) consultation because of stress. Research undertaken with 374 individuals seeking debt advice from a UK consumer advice service found that 62% reported that their debt problems had led to stress, anxiety or depression, and over a quarter of the total reported seeking GP treatment for this (Reference EdwardsEdwards, 2003). Reference Brown, Taylor and PriceBrown et al(2005) reported that heads of household who have outstanding non-mortgage debt are significantly less likely to report complete psychological well-being, whereas (in contrast to Nettleton & Burrows’ findings) no such association was found with mortgage debt.

Depression

Reference Reading and ReynoldsReading & Reynolds (2001) reported an association between debt and the development of postnatal depression in longitudinal research with 271 UK families. Although they were unable to conclude that debt caused the depression, debt was the strongest socio-economic predictor of depression. Research has also been conducted on financial strain (which differs from debt) and depression. Reference Chi and ChouChi & Chou (1999) in a longitudinal study of 554 elderly people in Hong Kong found that financial strain predicted increased depressive symptoms at 3-year follow-up (controlling for demographic, support and physical health variables). However, after a 3-year prospective community study of older individuals in the USA, Reference Mendes de Leon, Rapp and KaslMendes de Leon et al(1994) contended that financial problems were predictive of depression only in men, an effect modified by good physical health and social support.

Self-harm and suicidal ideation

In a community study of over 4000 Finnish participants, Reference Hintikka, Kontula and SaarinenHintikka et al(1998) found that difficulties in repaying debts during the previous 12 months (student loans, bank loans, credit cards, loans from friends/family) was an independent predictor of suicidal ideation. Furthermore, participants who had experienced repayment difficulties had marked mental symptoms more often than those who had not. A number of studies on debt have been conducted with people who self-harm. Reference Bancroft, Skrimshire and SimkinBancroft et al(1976) assessed patients who had taken overdoses and found those who stated that they had wished to die were more likely to have financial problems. In an uncontrolled study, Reference HatcherHatcher (1994) reported that people who were in debt were more likely to harm themselves, with greater suicidal intent, and would report more depression and hopelessness after the act. Meanwhile, Reference TaylorTaylor (1994) found that patients who self-harmed were more likely to be in debt than a control group of fracture clinic patients.

Social consequences

The impact of debt on individuals’ social relationships can be implicated in isolation and social exclusion, and in strain placed on existing relationships. Material deprivation is also associated with debt. Reference Drentea and LavrakasDrentea & Lavrakas (2000) have contended that individuals in debt will have less resources to spend on ‘quality’ goods (particularly those related to health and healthcare), as they attempt to make cutbacks to retain financial stability. Individuals who do make their debt repayments may be stretching themselves, with consequences for their health and social well-being. Finally, feelings of shame, social embarrassment and a sense of personal failure or other negative internalised identities associated with their debt may make individuals unwilling to disclose or discuss their financial situation (Reference HayesHayes, 2000).

Why do people get into problem debt?

Understanding why people with mental health problems might get into problem debt can provide psychiatrists with the knowledge to actively monitor for signs of this happening.

The influence of income

The most obvious explanation for problem debt is a lack of money, which may result in individuals borrowing money or delaying the payment of domestic bills. Lack of money may be the result of already living on a low income, but it can also arise from unexpected changes in income (such as job changes, redundancy or relationship breakdown). It follows that people with mental health problems are susceptible to debt: UK mental health service users often live on lower than average incomes; over 75% are reliant on welfare benefits (Office for National Statistics, 2002b ); unemployment rates are as high as 76% (Office for National Statistics, 2003). Furthermore, disruptions in benefit payments are often reported by individuals with mental health problems. Problem debt can also have an impact on carers, who may take on debts accrued by the person they care for, or incur debts because of the constraints that providing care can place on employment.

Mental health problems

Debt is triggered not only by income – specific mental health factors can also affect an individual's financial situation. These factors include the onset of mental illness, greater spending as a result of a condition (e.g. mania and spending sprees) and communication difficulties when an individual with a mental illness withdraws and does not acknowledge the problem. A small number of studies have considered the biological correlates of debt (Reference Grossi, Aleksander and LundbergGrossi et al, 2001; Reference Spinella, Yang and LesterSpinella et al, 2004), and some have described disorders such as ‘compulsive shopping disorder’, where debt is the salient feature of an impulse control failure (Reference BlackBlack, 2001; Reference Aboujaoude, Gamel and KoranAboujaoude et al, 2003). Other studies have taken a social perspective, and have contended that individuals may borrow money because of their unhappiness at being perceived and living as ‘mental patients’ – consequently attempting to purchase material goods and the apparently desirable lifestyle and identity marketed alongside them (Reference FitchFitch, 2006b ).

Socio-demographic characteristics

People in their 20s and 30s are more likely to have debt problems: Bank of England research has reported that 37% of those who found debt a ‘heavy burden’ were between 25 and 34 years of age (Reference Tudela and YoungTudela & Young, 2003). This may be due to life-cycle types of debt such as student loans, as well as to the greater likelihood in young adulthood of factors such as having children, setting up a new home and more liberal attitudes towards credit (Reference KempsonKempson, 2002). In addition, tenants are more likely than homeowners to report debt problems; single-parent families are more susceptible to debt than other family types; and women are overrepresented on most debt indicators (Department for Trade and Industry, 2005).

Availability of credit

The wider availability of credit in the UK during the past two decades has also played a role. It is due to two factors: the deregulation of financial markets in the 1980s; and the mid-1990s entry of US lenders into the market, which resulted in intensified competition, new initiatives, aggressive marketing and the targeting of new customer groups (including those on low incomes).

Although the voluntary Banking Code Standards Board (which sets standards for UK banking practice) stipulates that lenders should assess customers’ ability to repay before extending credit to them, only two of the following four criteria have to be taken into account: an income and expenditure budget, an assessment based on previous knowledge of the customer (account history), a credit score, or an external credit reference check. Health information does not form part of the credit application (unless someone with mental health problems voluntarily adds information to their credit reference file). Furthermore, in Britain it is illegal to deny credit to an individual on the basis that they have a mental health problem, unless evidence exists that the person does not have the capacity to understand the credit agreement (Disability Discrimination Act 2005; Mental Capacity Act 2005; Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000).

How does ‘debt’ become ‘problem debt’?

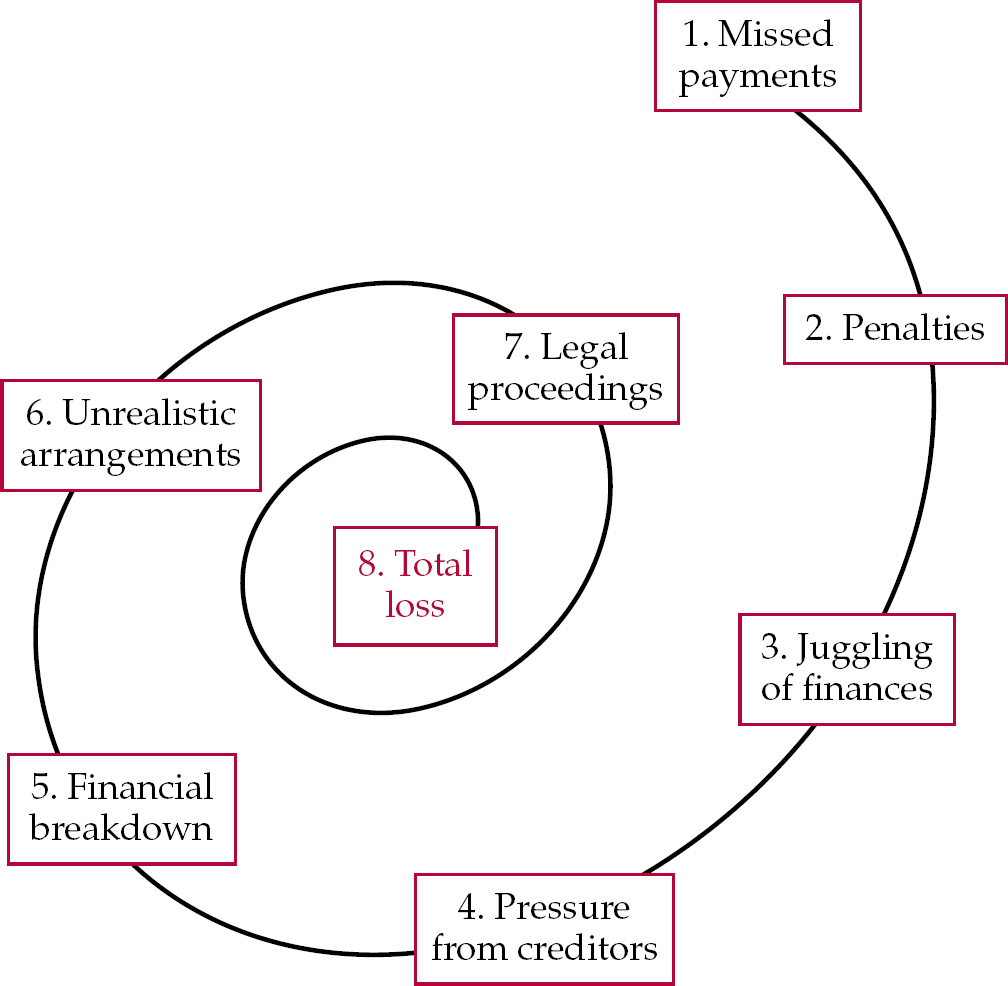

Understanding the stages and mechanisms through which a manageable debt becomes a problem debt can help professionals act before a full-blown crisis occurs. Below we outline one of the models used by those involved in debt counselling – the eight-stage ‘debt spiral’ (Fig. 1). Critically, intervention is possible at each stage.

Fig. 1 The debt spiral.

Missed payments and penalties

Missed payments are often the first symptom of debt problems. These can lead to penalties and heavy charges. Psychiatrists who become aware of a patient's credit arrangements (through inclusion of debt as an item for routine assessment) might consider proactively raising money matters – to identify whether the individual is coping with repayments, needs support and fully understands the financial implications of missed payments. Regular missed payments may indicate that the individual could be storing up future problems. If serious concerns exist, then an external debt advisor should be contacted.

Juggling finances

When missed payments occur, individuals often juggle their finances – paying the creditor who is applying the greatest pressure, or going without/cutting back on basic items (e.g. food or heating). Unfortunately, some people pay consumer credit bills, not realising that utility or rent arrears can have more serious legal consequences. Patients may also take out further loans.

Creditor pressure

Pressure from creditors can often build – unpaid creditors will make contact at this stage, with varying levels of understanding. Creditors may also transfer or sell on unpaid debts to debt collection agencies, whose demands are likely to be more intimidating and anxiety-provoking. The combined pressure of debt and creditor demands can generate enormous stress. If the patient is not already in touch with an external debt advisor, the psychiatrist should help to arrange this now.

Financial breakdown

One consequence of such pressure is that people often become overwhelmed and try to ignore what is happening. This can result in personal and financial breakdown, and it is at this point that the individual's mental health can be most affected. In seeking to address any such decline in mental health, psychiatrists have an opportunity to raise the issue of problem debt with patients. However, patients may not volunteer information about their debt, either not wishing to acknowledge it, or believing it might be seen as further proof of illness or failure to cope.

Unrealistic arrangements

Where creditors do make contact, individuals can make unrealistic repayment arrangements – because the creditor does not understand their position, or because the individual just wants the creditor off their back. All negotiations should be through an external debt advisor (if this option has been taken). However, some creditors also contact the individual directly, which can lead to a situation where one repayment figure is agreed with the advisor, then an often higher one is set with the patient.

Legal proceedings

Frequently, the individual will fail to keep to these unrealistic promises, and legal proceedings will begin. Depending on the type of debt, this can result in a court setting a repayment schedule (Griffiths Commission on Personal Debt, 2005). If this is not met, enforcement orders can be applied – these include sending in bailiffs, direct deductions from income and bankruptcy orders. For other types of debt, repossession, eviction, disconnection of service and (very rarely) imprisonment can be instigated. Finally, total loss can occur – this can be financial (creditors continuing to chase unpaid debts) or, in extreme cases, debt-related suicides (Reference Arehart-TreichelArehart-Treichel, 2005).

How should psychiatrists respond?

As noted in the next section, if people with mental disorders are deemed incapable of looking after their own financial affairs there are well-recognised steps that can be taken. These include the nomination of an individual to act on their behalf in managing assets (e.g. the ‘attorney’ system used in the Court of Protection in England and Wales), and the appointment of a person to receive and spend social security benefits (e.g. the ‘appointeeship’ system administered by the Department for Work and Pensions in England and Wales). However, psychiatrists can face difficult challenges when dealing with individuals who are accruing problem debt but have either not yet been deemed ‘incapable’, or who do have capacity.

Collaborative working already offers a solution to this problem – but its aims and operation may need to be re-evaluated. Community mental health team (CMHT) staff in the UK are well versed in arranging for patients to see debt advisors in external agencies (typically in the voluntary sector), where debt counselling and management are provided (Box 2). Some of these generic advice outlets (such as Citizens Advice and Money Advice Plymouth) employ or provide advisors trained in mental health awareness, while a handful of agencies also provide support to clients currently on psychiatric wards.

Box 2 Resources for people in debt

http://www.mhdebt.info

Guidelines, resources and links on debt and mental health

http://www.nationaldebtline.co.uk

Free specialist advice and help in the UK

http://www.citizensadvice.org.uk

Information on the nearest UK advice bureaux

However, there may be an understandable belief among some CMHT members that such external agencies offer a ‘magic bullet’, allowing them effectively to hand over the whole problem for the debt advice agency to resolve. In practice, this is unlikely to work. Psychiatrists should therefore encourage CMHT staff to initiate action prior to referral, to attend debt advice meetings to facilitate the patient–advisor relationship, and to have enough of a grasp on the overall process to proactively support the patient and advisor throughout. The CMHT role is integral, rather than peripheral.

During such work, psychiatrists and the CMHT can gain a clearer understanding of the debt advice process, allowing them to develop their own confidence and skills, and also better equiping them to answer ‘what will happen?’ questions from patients. It will also be advantageous if the CMHT are aware of what creditors can offer if asked. For example, the Royal Bank of Scotland has its own specialist mental health advisors and also allows customers with mental health problems to ‘flag’ accounts so that these can be monitored for unusual spending patterns. A similar flag may be placed on any UK individual's credit reference files (held by a credit reference agency), indicating that the individual does not want further loans.

Assessing mental capacity to make financial decisions

Fundamental to the assessment of a patient's ability to manage debt is the issue of mental capacity. Although it is important for individuals with mental health problems to manage their own finances when they are able to do so, a small minority need protection from their inability to make financial decisions or the risk of exploitation by others. Balancing the need for autonomy and self-determination against the need for protection is therefore a critical decision.

Due to come into force in England and Wales in April 2007, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (http://www.dca.gov.uk/menincap/legis.htm) will cover matters of capacity relating to financial decisions, as well as health and welfare. A detailed description of the Act is beyond this article (for a full review see Reference JonesJones, 2005). This new legislation will involve the formal adoption of functional tests of capacity that refer to specific decision-making processes. This contrasts with assessments of capacity based on status (e.g. diagnosis) or outcome (e.g. the type of decision made). However, although it is current best practice to use a functional approach, Reference Suto, Clare and HollandSuto et al(2002) found that in capacity assessments conducted by psychiatrists of people with a range of mental health problems, 74% involved a status approach.

One possible reason for this is the lack of any standardised measure or procedure for assessing a patient's mental capacity to make financial decisions. This is in stark contrast to the wide range of instruments designed to measure decision-making capacity regarding treatment. Below we present three guides to such capacity assessment.

Assessment models

One framework for the assessment of mental capacity to make financial decisions is provided by the British Medical Association & Law Society (Box 3). This is a dynamic model that accounts for the individual's history, the prognosis of their illness and changes in their financial situation. Other strengths are the highlighting of consequences for the patient (and others) of poor financial decision-making. However, it does not provide a clear operational framework for how to assess the basic skills required in budgeting.

Box 3 Checklist to guide assessment of mental capacity to manage property or affairs

Evaluate the extent of the person's property and affairs, including an examination of:

-

• income and capital (including savings and value of the home) expenditure and liabilities

-

• financial needs and responsibilities

-

• whether the person's financial circumstances are likely to change in the foreseeable future

-

• the skill, specialised knowledge and time it takes to manage the affairs properly and whether the mental disorder is affecting the management of the assets

-

• whether the person would be likely to seek, understand and act on appropriate advice where needed, in view of the complexity of the affairs

Personal information, which might include

-

• age and life expectancy

-

• psychiatric history

-

• prospects of recovery or deterioration

-

• the extent to which any incapacity could fluctuate

-

• the conditions in which the person lives

-

• family background

-

• family and social responsibilities

-

• cultural, ethnic or religious considerations

-

• the degree of back-up and support the individual receives or could expect to receive from others

The person's vulnerability:

-

• Could the person's inability to manage their property and affairs lead them to make rash or irresponsible decisions?

-

• Could inability to manage lead to exploitation by others – perhaps even by members of the person's family?

-

• Could inability to manage compromise or jeopardise the situation of other people?

(Adapted from British Medical Association & Law Society (2004), with permission of BMJ Books)

Arguing that mental capacity to make financial decisions is possibly the best predictor of whether an individual will be able to function independently in the community, Reference Marson, Savage and PhillipsMarson et al(2006) have developed a model that emphasises the assessment of financial skills. This is outlined in Box 4. The clinician is required to assess, for example, the patient's ability to calculate the value of coins, purchase items, use a chequebook, pay bills and budget on a weekly basis. The assessment requires tasks involving knowledge, calculations and the use of reasoning. Less emphasis is placed on the broader context of financial decision-making.

Box 4 Assessing the financial decision-making capacity of people with severe mental illnesses

Individuals are assessed on their ability to carry out the tasks listed in the following five domains

Basic money skills

-

• Define the simple concept of money

-

• Identify specific coins/currency

-

• Identify the relative worth of coins/currency

-

• Count coins/currency accurately

Cash transactions

-

• Identify the cost of a single item from its price tag

-

• Use coins/currency to make a purchase

-

• Explain additional charges such as sales tax

Understanding chequebooks

-

• Explain what a chequebook is

-

• Pay by cheque in a simulated transaction

Bill payment

-

• Explain what a bill is

-

• Identify how much is owed on a bill

-

• Explain how to make enquiries about a bill

-

• Explain the consequences of unpaid bills

Budgeting

-

• Explain what a budget is

-

• Budget expenses using a weekly or monthly benefits payment

-

• Explain the budget choices made

By informal questioning the assessor also asks the individual about:

-

• any representative payee (the person appointed to manage benefit payments if the individual is unable to)

-

• their history with money:

-

• current financial arrangements/activities

-

• prior money problems

-

• areas in which they would like financial assistance

-

The assessor can then judge the individual's overall financial capacity, in terms of:

-

• capacity to manage financial affairs

-

• strengths and weaknesses

-

• the need for supervision

(Adapted from Reference Marson, Savage and PhillipsMarson et al, 2006. With permission from Oxford University Press)

The two assessment frameworks have in common the need to be aware of the individual's current financial arrangements and both serve as a guide in making a decision based on overall clinical judgement.

Vignettes about situations requiring financial decisions are used in a model to assess the mental capacity of people with intellectual disabilities (Reference Suto, Clare and HollandSuto et al, 2005). These vignettes include, for example, making decisions when buying items in a supermarket, deciding whether to go to work and paying for car repairs. For each vignette, capacity is assessed across four domains: understanding, appreciation, reasoning and communication. Using the instrument Suto et al found that 40% of people with an intellectual disability (mean IQ = 61) obtained full scores on at least one question; understanding was the most problematic area of capacity; and measured capacity declined as the required decision became more complex. Consequently, although people with intellectual disabilities performed less well than a comparison group with normal intellectual ability, many were able to make some financial decisions.

It may be beneficial to combine the three approaches described above with detailed enquiry into the specific financial skills necessary for the person's life (including the history, consequences and likelihood of change in these skills, and the exploration of common hypothetical situations where decisions are necessary), as well as the individual's mental capacity to understand, retain and deliberate on this information, and to take and express a decision.

Conclusions

Over the past two decades, debt has become a component of modern life in the UK and elsewhere. There is evidence to suggest that people with mental health problems are more susceptible to debt and arrears than those without such conditions, and these can lead to associated financial, health and social consequences. However, little information is available to psychiatrists and health professionals on what they should know and do to assist patients with problem debt.

The challenges of patient debt for psychiatrists are likely to become more apparent over the coming years. First, it is probable that existing levels of debt across UK society will continue to increase well above inflation or earnings, and that the burden of debt will be carried by socially vulnerable groups. Second, with the implementation in England and Wales of the Mental Capacity Act in 2007, discussions about ‘financial capacity’ (and the role of the psychiatrist in assessing it) are likely to intensify as unanticipated scenarios arise. Third, new guidance specifically focused on dealing with people with mental health problems who are in debt will also be delivered to the UK financial services industry in 2007. Formulated by a working group of the credit industry, debt advice agencies and mental health organisations, this will contain recommendations on best practice and liaison with medical professionals, carers and people with mental health problems.

Declaration of interest

The costs of printing and disseminating copies of the booklet Final Demand: Debt and Mental Health. Debt and Arrears: What Service Users Want Health Workers to Know and Do (Reference FitchFitch, 2006a ) have been partially financed by a grant from the Finance and Leasing Association to C.F.

MCQs

-

1 The proportion of people with mental health problems reporting debt or arrears is:

-

a one in eleven

-

b one in four

-

c one in six

-

d one in nine.

-

-

2 With reference to the ‘debt spiral’ model, the first symptom of a debt problem is often:

-

a legal proceedings

-

b juggling of finances

-

c missed payments

-

d penalties.

-

-

3 Studies have reported that:

-

a people assessed after an act of self-harm who were in debt were more likely to state that they had intended to die

-

b people assessed after an act of self-harm who had problem debts had usually already received help

-

c patients in an A&E department because they have harmed themselves are not at greater risk of debt than control patients from a fracture clinic

-

d debt is not an independent predictor of suicidal ideation in the general population.

-

-

4 As regards the assessment of mental capacity to make financial decisions:

-

a the Mental Capacity Act requires a status approach to the assessment of capacity

-

b most doctors when referring patients to the Court of Protection for management of finances use a functional approach to the assessment of capacity

-

c the mental capacity of a patient with schizophrenia to make financial decisions is a good indicator of ability to function independently in the community

-

d people with learning disability have been shown to lack capacity on all domains.

-

-

5 A community mental health team may help people with severe mental illness who are in debt by:

-

a discharging them with the advice to contact a debt advice agency

-

b supporting them to obtain further borrowing in order to pay off debts

-

c working collaboratively with a debt advice agency

-

d not focusing on debt as it is a relatively unimportant contributor to an individual's ability to live with mental illness in the community.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | T | b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T | c | T |

| d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.