Mental healthcare reforms in the 2000s have promoted the transfer of treatment and follow-up for individuals with mental disorders to the community, as an alternative to hospital services. Reference Thornicroft and Tansella1 In the context of this shifting paradigm in mental healthcare, the Quebec Health Ministry (Canada) launched a Mental Health Action Plan in 2005 that supported the strengthening of community mental healthcare services and promoted recovery best practices to improve quality of life (QoL). Reference Bouchard and Breton2 Recovery has been defined as ‘a deeply personal, unique process of changing one's attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and/or roles … it is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by illness’. Reference Anthony3 Most high-income countries have engaged in mental health system reform over the past two decades in order to improve service performance by increasing continuity and accessibility of services, and adopting innovations like recovery-oriented practices to better respond to client needs. The goal of the reform under study was to enhance the recovery orientation of services by acknowledging that individuals with mental disorders should play a central role in treatment decisions and service orientation. Needs assessment is becoming a key component in measuring recovery among individuals with mental disorders. Reference Slade, Leese, Ruggeri, Kuipers, Tansella and Thornicroft4 Knowing more about the relationship between patient needs and service performance may inform the development of better treatment plans and help improve patient outcomes like recovery and QoL. Studies have explored relationships between needs, service performance and outcomes; Reference Killaspy, Marston, Omar, Green, Harrison and Lean5 yet, to our knowledge, no research to date has studied these three components simultaneously.

This study represents a first step in the evaluation of this reform within the theory of change (ToC) theoretical framework. ToC provides a conceptual framework for generating knowledge about the extent to which reform is effective in specific local contexts. Reference Weiss, Connell, Kubisch, Schorr and Weiss6 ToC allows us to generate causal pathways that describe how specific elements in organisational change may be expected to achieve the desired impact within particular settings. Reference De Silva, Breuer, Lee, Asher, Chowdhary and Lund7 The first step in developing a ToC model is to identify inputs: for the present study inputs were defined as the needs of patients with mental disorders. Second, the outcomes targeted by services are defined; here, quality of life and personal recovery were identified as the ultimate aims of mental healthcare according to the recovery model. Reference Anthony3 Finally, ToC requires identification of preconditions for achieving the desired outcomes. A number of factors may influence service performance in the context of system reform, for example shifting financial or human resources, leadership, interorganisational collaboration. This study hypothesised that the reorientation of services toward recovery, Reference Killaspy, Marston, Omar, Green, Harrison and Lean5 as well as improved continuity of care Reference Green, Polen, Janoff, Castleton, Wisdom and Vuckovic8 and adequacy of help received (i.e. the ability of providers to meet patient needs) Reference Jerrell, Cousins and Roberts9 were preconditions for enhancing recovery and QoL in patients. The study favoured subjective measures of service performance from a patient, rather than professional, perspective and eschewed other proxy measures for service performances such as administrative data (for example, frequency of visits to specialised mental health services, delay between hospital discharge and initial out-patient treatment), as these administrative measures, although considered objective, are weakly related to improved outcomes. Reference Greenberg, Rosenheck and Seibyl10 To our knowledge, no research to date has studied the putative mediational role of service performance between patient needs and outcomes. The objective of the current study was to develop and validate a ToC pathway that may explain the impact of the Quebec reform in terms of patient perceptions of their needs, service performance for the services they used, and patient outcomes, using structural equation modelling (SEM).

Method

Definition of the model

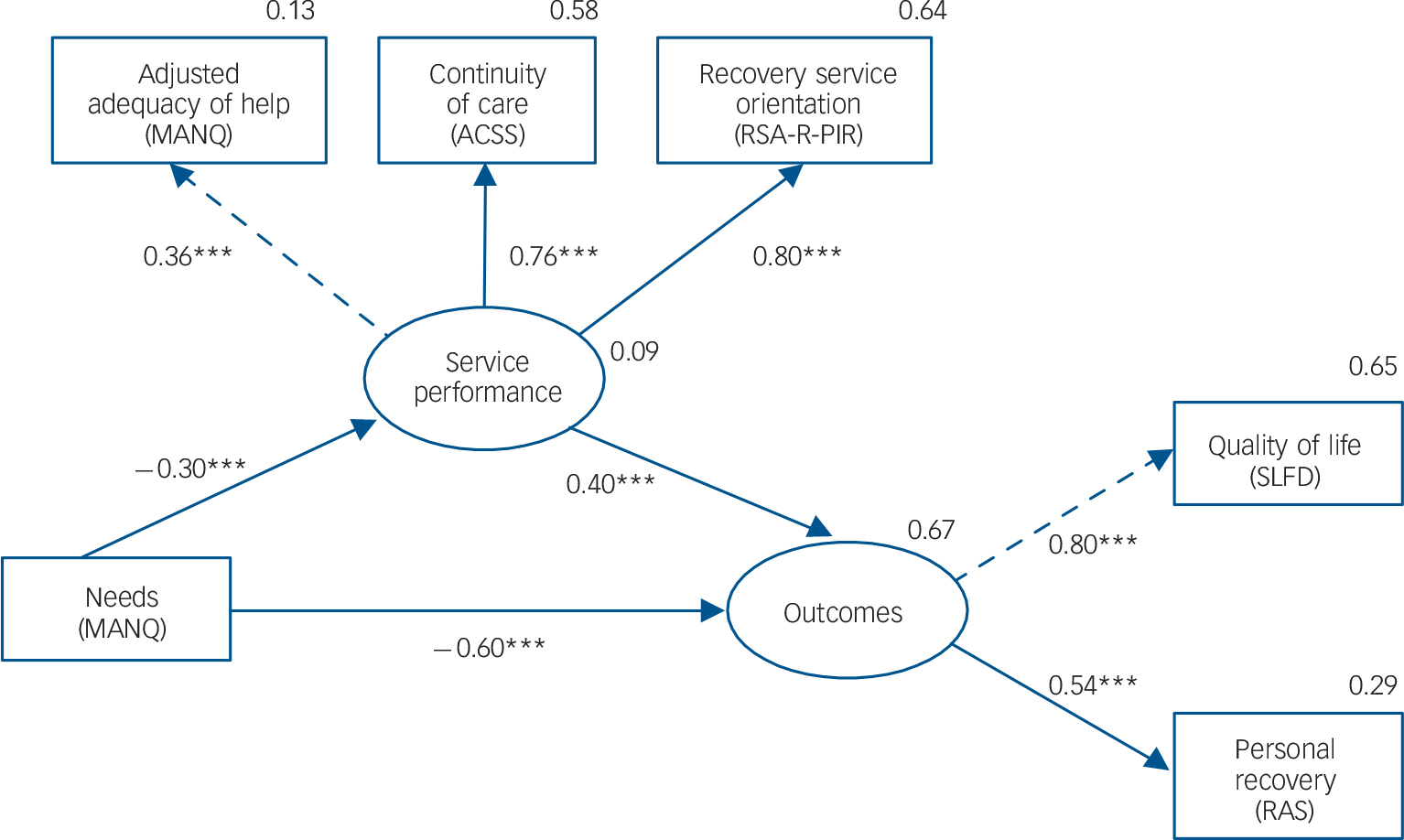

Figure 1 presents a predictive model for the mediating role of service performance in mental healthcare based on the hypothesis that the negative impact of patient needs on outcomes will be partially mediated by a decrease in service performance.

Fig. 1 Mediation model.

Circles represent unobserved latent variables. Rectangles represent observed measured variables. Arrows with dashed lines are drawn between a latent variable and its reference indicator with a corresponding unstandardised regression fixed to a weight of one (in order to fix the unit of measurement of each unobserved variable). Arrows with solid lines are drawn between variables with free regression weight. Values are standardised path coefficients. The squared multiple correlation (R2) value for the dependent variable appears above its circle or rectangle. MANQ, Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire, ACSS: Alberta Continuity of Services Scale for Mental Health, RSA-R-PIR: Recovery Self-Assessment, revised person-in-recovery version, SLDS: Satisfaction with Life Domains Scale, RAS: Recovery Assessment Scale. ***P<0.001.

Definition of latent variables

Quality of life (QoL) and recovery were indicator variables of the latent variable outcome: these two dimensions usually correlate with one another. Reference Corrigan, Salzer, Ralph, Sangster and Keck11 The second latent variable was service performance, which included adequacy of help, continuity of care and recovery orientation of services. Research suggests that these three indicator variables are closely related. For example, meeting patient needs is a key quality dimension in mental health services. Reference Turton, Wright, White, Killaspy and Group12 The quality of services also relies heavily on recovery-based practice Reference Killaspy, White, Wright, Taylor, Turton and Schutzwohl13 and continuity of mental healthcare. Reference McCallum, Mikocka-Walus, Turnbull and Andrews14 Continuity of care is enhanced when the philosophy of care fits the recovery paradigm Reference Erskine, Baumgartner and Patterson15 and is usually greater when mental health services meet patient needs more adequately. Reference Mojtabai, Fochtmann, Chang, Kotov, Craig and Bromet16 Stakeholders often consider that providing adequate help by meeting patient needs after discharge is one component of care that promotes the recovery orientation of services. Reference Turton, Wright, White, Killaspy and Group12

Relationship between latent variables

Greater need for care is usually associated with worse outcomes for individuals with mental disorders, in terms of QoL Reference Fleury, Grenier and Bamvita17 and recovery. Reference Lloyd, King and Moore18 Needs may also have a detrimental effect on service performance: greater problem severity in relation to mental health correlated with lower continuity of care on both patient- and observer-rated scales. Reference Adair, McDougall, Mitton, Joyce, Wild and Gordon19 Moreover, the adequacy of help provided by services decreased with more severe mental health needs. Reference Fleury, Bamvita, Grenier, Schmitz, Piat and Tremblay20 Finally, staff–patient agreement on needs was negatively associated with severity of needs. Reference Lasalvia, Bonetto, Tansella, Stefani and Ruggeri21 Given that staff–patient consensus regarding service needs is a crucial component in recovery-oriented services, this result is compatible with the hypothesis that severity of needs will be negatively associated with a recovery orientation in services.

Service performance is crucial in improving patient outcomes. First, adequacy of help is positively associated with recovery in individuals with severe mental disorders. Reference Jerrell, Cousins and Roberts9 For example, self-reported unmet needs, which suggest inadequacy of help, are associated with lower QoL in patients with severe mental disorders, even after controlling for the confounding effect of met needs. Reference Wiersma and van Busschbach22 Second, continuity of care is associated with better QoL and better community functioning in individuals with severe mental disorders. Reference Adair, McDougall, Mitton, Joyce, Wild and Gordon19 Finally, recovery-oriented services have been associated with better QoL and recovery. Reference Green, Polen, Janoff, Castleton, Wisdom and Vuckovic8 In sum, we developed the following hypotheses for the present study: patient needs will be negatively associated with outcomes; patient needs will be negatively associated with service performance; service performance will be positively associated with outcomes.

Study design and network characteristics

This study used a cross-sectional design. The study population included adults with mental disorders in Quebec who were followed in four local mental health service networks in different geographical areas: three networks were located in urban areas including the two most populous cities in Quebec, and one in a semi-urban area. Each local mental health service network included a hospital department of psychiatry and a multidisciplinary mental health primary care team (an out-patient team composed of psychosocial clinicians, general practitioners and psychiatrists). The networks also included community-based mental health agencies (for example, crisis centres, day centres, self-help groups and employment integration programmes), general practitioners and psychologists practising in private clinics, and community mental health housing resources (such as intermediary residences, foster homes).

Participants

To participate in the study, participants had to be between 18 and 70 years old and diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, or other conditions including mood, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive, personality, attention-deficit hyperactivity or stressor-related disorders according to the DSM-V. 23 This broad diagnostic spectrum ensured the representation of patients with a diversity of needs. The study excluded individuals who had been admitted to hospital in the 3 months prior to the study, or who were too clinically unstable to allow for reliable data collection. The clinical stability and the ability to give fully informed consent were assessed by clinicians and the research team, which included psychiatrists. The investigators checked whether patients were capable of completing the full data collection process, and of comprehending and retaining information about the research. Individuals with a severe intellectual deficit were also excluded, as well as those receiving involuntary psychiatric treatment under judicial order, who may have been unable to provide informed consent for participation in the study.

Various recruitment strategies were used, including self-referral in response to posters displayed at hospitals or health and social service centres. Information sessions were held, and flyers explaining the project produced for mental healthcare providers and housing resources staff in the mental health networks. The research team worked closely with an advisory committee comprised of decision makers from the mental health networks for the recruitment and data-collection phases. Data were collected from June 2013 to August 2014. Professional interviewers trained by the research team conducted two 90 min interviews at 1-week intervals with each participant. The interviewers maintained close contact with the research team to ensure quality data collection. Participants other than self-referrals were contacted by their primary healthcare provider, who gauged their interest in participating in the study and referred potential participants to the research team. After the study was described to them, participants were required to sign a consent form. The multisite study protocol was approved by the Ethics Board of the Douglas Mental Health University Institute (reference number: 07/35). Participants were required to give permission for the research team to access their medical records.

Measures

Five questionnaires were used to collect data. Patient needs and adequacy of help received were assessed using the Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire (MANQ), Reference Fleury, Grenier, Bamvita, Piat and Tremblay24 which was derived from the Camberwell Assessment of Needs (CAN). Reference Phelan, Slade, Thornicroft, Dunn, Holloway and Wykes25 The MANQ added four areas of need (adaptation to stress, social exclusion, involvement in treatment decisions and job integration) to the 22 areas of need established by the CAN, for a total of 26. While the CAN measures the severity of needs and adequacy of help received based on three ordinal scale questions, the MANQ uses three analogical scales, ranging from 0 to 10, identifying more precisely each of 26 possible areas of need (10, greatest severity or adequacy), and enhancing data variability. Whereas ratings on the CAN are usually provided by professionals, patient needs in this study were assessed by participants themselves using the MANQ, with the help of interviewers. As such, the response modality of the MANQ represents a better fit with the recovery perspective than that of the CAN. Another improvement in the MANQ over the CAN concerns the clear analytical distinction in the MANQ between severity of needs and adequacy of help received. The CAN categorises needs in terms of: ‘no need’, ‘met need’ and ‘unmet need’, which conflates the severity of need with the adequacy of help to meet the need. By contrast, the MANQ focuses on severity of need as the intensity of need, irrespective of whether the need was met or not.

A total score for severity of needs was computed for each participant by summing the severity scores for all areas of need (range 0–260). The MANQ severity of needs measure has been validated for test–retest reliability (kappa coefficient ranged from 0.74 to 1.00); and interrater reliability (kappa coefficient ranged from 0.79 to 1.00). The factorial structure and convergent validity with other instruments have also been established for the MANQ. Reference Fleury, Grenier, Bamvita, Piat and Tremblay24,Reference Tremblay, Bamvita, Grenier and Fleury26

Service performance was evaluated using three standardised instruments: the MANQ measured adequacy of help received from both qualitative (type of support) and quantitative (amount of support) perspectives using two separate analogical scales. An adjusted score for adequacy of help received was computed for each participant by summing the two adequacy scores for all areas of need (range 0–520) and then dividing this overall score by the number of needs with a severity greater than 0. For example, an individual reporting two needs, one with a severity of 5, a quantitative adequacy of 4 and a qualitative adequacy of 3, and the other with a severity of 8, a quantitative adequacy of 2 and a qualitative adequacy of 1 would have a severity score of 13 and an adjusted adequacy of help received of 5. The introduction of this adjustment measure was necessary given significant variation in the number of reported needs. Reference Fleury, Bamvita, Grenier, Schmitz, Piat and Tremblay20 Adequacy of help received for the MANQ has been validated for internal consistency (Cronbach alpha α = 0.91, see online supplement DS1) and for convergent validity with the CAN. Reference Fleury, Grenier, Bamvita, Piat and Tremblay24 All other scales used to assess service performance were ordinal self-report instruments. Continuity of care was measured with the Alberta Continuity of Services Scale for Mental Health (ACSS, 43 items, five Likert-scale response levels, Cronbach's α = 0.78–0.92). Reference Durbin, Goering, Streiner and Pink27 Recovery-orientation of services was evaluated with the Recovery Self-Assessment Scale, revised person-in-recovery version (RSA-R-PIR, 32 items, five Likert-scale response levels, Cronbach alpha α = 0.94). Reference O'Connell, Tondora, Croog, Evans and Davidson28

Outcomes were evaluated with two standardised instruments: QoL was assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Domains Scale (SLDS, 20 items, seven Likert-scale response levels, Cronbach's α = 0.92); Reference Caron, Mercier and Tempier29 personal recovery was assessed with the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS, 41 items, five Likert-scale response levels, Cronbach's α = 0.76–0.97). Reference Salzer and Brusilovskiy30

Statistical analyses

First, zero-order correlations between each measure were performed and Pearson's correlation coefficients calculated. The statistical significance of each test was computed from standard error estimates using the bootstrap method with 2000 iterations. We then performed an SEM and mediation analysis to examine the relationships among needs, service performance and outcomes, using the lavaan package Reference Rosseel31 of R statistical software (version 3.2.2). The required sample size for completing SEM analysis is a minimum of five participants for each estimated parameter. Reference Hair32 In this study, 15 parameters were estimated, requiring a minimum of 75 participants. Factor loadings were used to specify the association between the unobservable constructs (latent variables) and their theoretically related measures (indicator variables). Regression analyses determined the relationships among latent variables and were indexed by standardised path coefficients. The independent variable, needs, was calculated as the total score for severity of needs on the MANQ. The latent mediator variable, service performance, was indexed with three indicator variables: adjusted adequacy of help received score, ACSS total score and RSA-R-PIR total score. The latent variable, outcome, was indexed with two indicator variables: SLDS and RAS total scores. The model used to estimate potential mediation effect posits a direct relationship between needs and outcome, and an indirect relationship between these two variables through their linkages with service performance (Fig. 1). For the mediation analysis, direct effect refers to the standardised path coefficient between needs and outcome, and indirect effect to the product of the standardised path coefficient between needs and service performance with the standardised path coefficient between service performance and outcome. The total effect of needs on outcome is the sum of direct and indirect effects. The proportion of the effect of needs on outcome that is mediated by service performance is calculated as the indirect effect divided by the total effect. Standard errors for factor loadings and standardised path coefficients for the SEM analysis, as well as direct, indirect, total and proportional mediated effects for the mediation analysis, were estimated using non-parametric, model-based bootstrapping with 2000 iterations. Mediation occurred if the indirect effect was significant. The mediation was considered partial if the direct effect was also significant.

The model fit, which represents how an SEM fits with the sample data, was assessed using three indices: the chi-squared goodness-of-fit statistic (χ2) where significance was tested using the Bollen–Stine bootstrap method, the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) and the root-mean-squared error of approximation (RMSEA).

Results

Participants

A total of 339 patients were recruited in the study, for an overall response rate of 81.2%. The size of patient subsamples recruited in the four mental health service networks ranged from 58 to 121. Missing data were estimated using multivariate imputations by chained equation (with 50 multiple imputations) in the mice package of R. Reference Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn33 Table 1 presents sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants, and Table 2 provides data on needs, service performance and outcomes. The mean patient age was 48.5 years, and 49% of respondents were men. Most participants were single, lived autonomously in an apartment and had not completed post-secondary education.

Table 1 Participants' sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (n = 339)

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 48.5 (11.4) |

| Number of children, mean (s.d.) | 0.6 (1.1) |

| Gender, men: % | 49 |

| Education, higher than secondary school: % | 39.2 |

| Civil status, % | |

| Married/remarried/common law | 15.6 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 14.2 |

| Single/never married | 70.2 |

| Type of housing, % | |

| Single dwelling | 66.7 |

| Intermediary resource | 5.0 |

| Foster home | 10.6 |

| Temporary housing | 10.3 |

| Supervised apartment | 7.4 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis, a % | |

| Schizophrenia spectrum or other psychotic disorder | 50.3 |

| Bipolar or depressive disorder | 48.6 |

| Anxiety or obsessive–compulsive disorder | 24.0 |

| Personality disorder | 33.3 |

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 4.6 |

| Trauma- and stressor-related disorder | 10.6 |

| Co-occurring substance use disorder | 13.3 |

a. The analysis of primary diagnoses revealed the following distribution: 49.4% schizophrenia spectrum or other psychotic disorders, 42.6% bipolar or depressive disorders, 3.8% anxiety or obsessive–compulsive disorders, 2.7% personality disorders, 1.2% trauma- and stressor-related disorders and 0.3% attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders.

Table 2 Participant evaluation of needs, service performance and outcomes (n = 339)

| Domain (scale, range) | Mean (s.d.) |

|---|---|

| Needs | |

| Intensity of needs (Montreal Assessment of Needs | |

| Questionnaire (MANQ), 0–260) | 48.5 (33.1) |

| Service performance | |

| Adjusted adequacy of help (MANQ, 0–20) | 8.7 (5.2) |

| Continuity of care (Alberta

Continuity of Services Scale for Mental Health, 43–215) |

132.6 (16.4) |

| Recovery service orientation

(Recovery Self-Assessment, revised person-in-recovery version, 32–160) |

116.9 (19.2) |

| Outcomes | |

| Quality of life (Satisfaction

with Life Domains Scale, 20–140) |

96.8 (18.7) |

| Personal recovery (Recovery Assessment Scale, 41–205) | 160.8 (20.5) |

Mood and psychotic disorders were most prevalent and equally represented in the sample and 43.3% of patients had at least two diagnoses. The mean score for severity of needs on single items was 1.9, which corresponds to moderate need. QoL was moderate, with a mean score for single items of 4.8. The single-item mean score for RAS was 3.7, corresponding to moderate recovery. Overall, participants judged that services were moderately oriented towards recovery, with a single-item average score of 3.7 on the RSA-R-PIR.

SEM and mediation analysis

Zero-order correlations between the indicator variables are presented in online supplement Table DS1. The model provided a good fit for the data, as suggested by the following statistics: non-significant goodness-of-fit based on the Bollen–Stine bootstrap distribution ((7) = 14.3, P= 0.107), TLI above 0.95 (TLI = 0.967) and RMSEA not statistically greater than 0.05 (RMSEA = 0.056, one-sided P = 0.358). The model explained 67% of the variance in patient outcomes. All indicator variables were reliable and valid measures of their respective latent variables, as supported by significant moderate to high factor loadings (standardised β = 0.36–0.80, P<0.001, see online Table DS2 and Fig. 1).

In summary, the analysis revealed the following relationships between the latent variables (Fig. 1): (a) a significant negative association between needs and outcomes; (b) a significant positive association between service performance and outcomes; (c) a significant negative association between needs and service performance.

Direct, indirect and total effects were all significant (see Table 3 and Fig. 1), suggesting a partial mediation role for service performance between needs and outcome. We found that 16.4% of the total effect of needs on outcome was mediated by service performance (standard error: 0.05, z = 3.6, P<0.001 with the Bollen–Stine bootstrap method after 2000 iterations).

Table 3 Statistics for the mediation analysis

| Effect | Standardised coefficients |

Standard error a |

z | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect | −0.12 | 0.03 | −3.6 | <0.001 |

| Direct | −0.6 | 0.06 | −10.8 | <0.001 |

| Total | −0.72 | 0.05 | −14.9 | <0.001 |

a. Standard errors were estimated using model-based bootstrapping with 2000 iterations.

Discussion

This study explored whether service performance mediates between patient needs and outcomes among individuals with mental disorders in the context of a major mental health reform in Quebec, as one case example of many healthcare reforms conducted internationally.

Mean scores on severity of needs, ACSS, adjusted adequacy of help received and QoL for participants in this study were similar to the findings in other studies that focused solely on severe mental disorders. Reference Fleury, Grenier and Bamvita17,Reference Fleury, Bamvita, Grenier, Schmitz, Piat and Tremblay20 RAS scores were not different from the average scores produced by a meta-analysis involving individuals with various mental health disorders. Reference Salzer and Brusilovskiy30 The average score for single items on the RSA-R-PIR was 3.7, which was slightly lower than the score of 4.06 reported by O'Connell et al for a mixed sample of individuals followed in mental health and addiction services. Reference O'Connell, Tondora, Croog, Evans and Davidson28 The consistency between our results and those in this previous study suggests that our findings may be generalisable to patients with mental disorders located in similar settings, using the same instruments.

Interpretation of the main findings

Overall, our results confirm the three hypotheses related to the ToC pathway, in which needs, service performance and outcomes are considered to be significantly associated. The study represents the first step toward validating a ToC pathway suggesting that improved service performance is an important requisite to achieving improved recovery outcomes in individuals with mental health disorders. Service performance was perceived as lower for users with high v. low needs, which may be explained by the fact that some needs were likely ‘unmeetable’, for example because of a lack of effective treatment for refractory symptoms, or in cases where patients reject treatments. Mental health services also fall short in meeting needs in domains other than health-related needs Reference Fleury, Grenier, Bamvita, Piat and Tremblay24 because of a lack of coordination between the mental healthcare system and inter-sectoral resources such as social services, housing, education and employment. Reference Cummings and Kropf34 Social networks among individuals with the highest needs tend to be very limited; relationship needs are quite difficult for mental health services to address, as well. Services that are insufficiently recovery-driven might lead to increased needs for information concerning illness and treatment, as well as limited patient involvement in treatment decisions. However, needs accounted for only a small proportion of the variance in service performance, suggesting that service performance may also be influenced by factors unrelated to patient-level conditions, for instance living conditions (numbers of residents in residential facilities, physical environment, and restrictiveness), accessibility of services, staff training and clinical governance. Reference Taylor, Killaspy, Wright, Turton, White and Kallert35 The link between continuity of care and better outcomes in the findings might be explained by an improved therapeutic alliance and increased patient involvement in treatment with close and continuous follow-up. Reference Junghan, Leese, Priebe and Slade36 An enhanced culture of recovery in services is usually associated with better employment rates and more stable housing, Reference Henneker and Reed37 thus leading to an improvement in perceived patient recovery, Reference Wilrycx, Croon, Van den Broek and van Nieuwenhuizen38 and QoL, in patients with psychiatric disorders. Reference Slade, Bird, Clarke, Le Boutillier, McCrone and Macpherson39

Service performance was a partial mediator between needs and outcomes: services were less efficient (i.e. less continuous, less adequate, less recovery-oriented) for patients with the highest needs, and this negatively affected outcomes (worse recovery and worse QoL), beyond the direct effect of severity of needs. The variables included in the model accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in outcomes, which suggests good validity for the ToC pathway under study. However, further dimensions should be taken into account in developing an overarching model of change induced by mental health reform, for example, implementation of the reform.

Limitations

The study involved certain limitations. First, causal relationships between needs, service performance and outcomes cannot be established with certainty. In the model, it was hypothesised that the direction of causality started from service performance to outcomes. However, one might argue that the direction of this relationship could be reversed: patients with better outcomes might see services as more efficient because of a tendency to perceive the environment in a more optimistic way. A longitudinal study with several measurement periods would be required to disentangle between the two directions of causality, using, for example, the methodology of crossed-lagged effects. Second, individuals recently admitted to hospital prior to the study or subject to a legal order were excluded from the study, which may have introduced a sampling bias to the detriment of patients with the highest needs. Third, data about potential participants who presented with criteria for exclusion were not systematically collected. It was thus not possible to evaluate the proportion of the sampling pool excluded on the basis of these criteria. Finally, our measure of adequacy of help received did not distinguish between unmet needs and needs that were unmeetable. However, unmeetable needs represent only a small minority of the needs observed in mental health. Reference Boardman, Henshaw and Willmott40

Implications

The findings of this study have important implications for clinical care, policy-making and service development. To our knowledge, this research is the first to introduce a comprehensive ToC model in order to assess relationships between severity of needs, service performance and outcomes. These findings underline the critical importance of mental healthcare reforms aimed at improving services' performance by promoting close follow-up of individuals with high mental-health-related needs. Community-based mental health agencies usually lack financial resources and have struggled to adequately serve individuals with the highest needs in mental health following system-level reform. In addition, the continuity between mental health and other services is usually insufficient to address acutely severe needs in the context of a recovery-oriented service system. Reference Bengtsson-Tops41

To conclude, the fact that service performance mediated the relationship between patient needs and outcomes, and that services were less effective for people with greater needs, provide justification for more investment in specialist services for people with complex needs in mental health. Programmes promoting recovery-oriented services such as supported employment, assertive community treatment and intensive case management that target patients with the most severe needs may help improve recovery, as well as QoL, for this vulnerable population.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Institut de Recherche en Santé Publique (Programme handicap et perte d'autonomie 2014 –Session 5 – Contrat de définition), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR-#243589) and the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the individuals who participated in the research. We are also grateful to Denise Aubé, Jean-Marie Bamvita, Geneviève Cyr, Guy Grenier, Judith Sabetti and Catherine Vallée for their valuable help with this study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.