Cross-culturally, dogs (Canis familiaris, Linnaeus 1758) are often valued members of societies, as expressed in the commonality of their inhumation, a practice rarely seen with other animals (Russell Reference Russell2011). Within the precolumbian Caribbean, the role of dogs was that of a hunting aid, a companion, and potentially a food source (Grouard et al. Reference Grouard, Perdikaris and Debue2013; Las Casas Reference Las Casas1876 [1561]). Earlier studies on precolumbian Caribbean dogs assessed morphological differences (Grouard et al. Reference Grouard, Perdikaris and Debue2013) and provided isotopic evidence of dietary and mobility patterns (Laffoon et al. Reference Laffoon, Esther Plomp, Davies, Hoogland and Hofman2015, Reference Laffoon, Hoogland, Davies and Hofman2019). This article provides additional morphological data and is the most expansive investigation of Caribbean C. familiaris isotopic values conducted to date.

Multi-isotopic analyses of precolumbian dogs in the insular Caribbean have primarily focused on enamel samples, with some collagen samples from El Flaco and El Carril in the Dominican Republic (Shev Reference Shev2018) and from Punta Candelero in Puerto Rico (Pestle Reference Pestle2010). Laffoon and colleagues (Reference Laffoon, Hoogland, Davies and Hofman2019) incorporated strontium (87Sr/86Sr) and carbon (δ13C) isotope values from El Flaco and El Cabo in the Dominican Republic and from Morel and Anse à la Gourde in Guadeloupe, demonstrating similarities between human and dog diet and mobility patterns at these sites. These human–dog linkages were previously reported globally in diverse archaeological contexts, leading to the proposition of a “canine surrogacy approach” in which dogs could be used as an isotopic surrogate for human remains (Guiry Reference Guiry2012).

An earlier study by Grouard and coauthors (Reference Grouard, Perdikaris and Debue2013) assessed the morphology of buried dogs from the region, indicating some differences in estimated withers heights (Grouard et al. Reference Grouard, Perdikaris and Debue2013). These data suggest there may have been more than one variety of dog within the insular Caribbean. This notion may be supported by Las Casas, who reported the existence of two different breeds that may have received different treatment by humans (Reference Las Casas1876 [1561]). In our study, we assessed the withers heights of dogs from El Flaco and El Carril to determine whether there are correlations between morphology and differential treatment in the form of formal burials or dietary regimes.

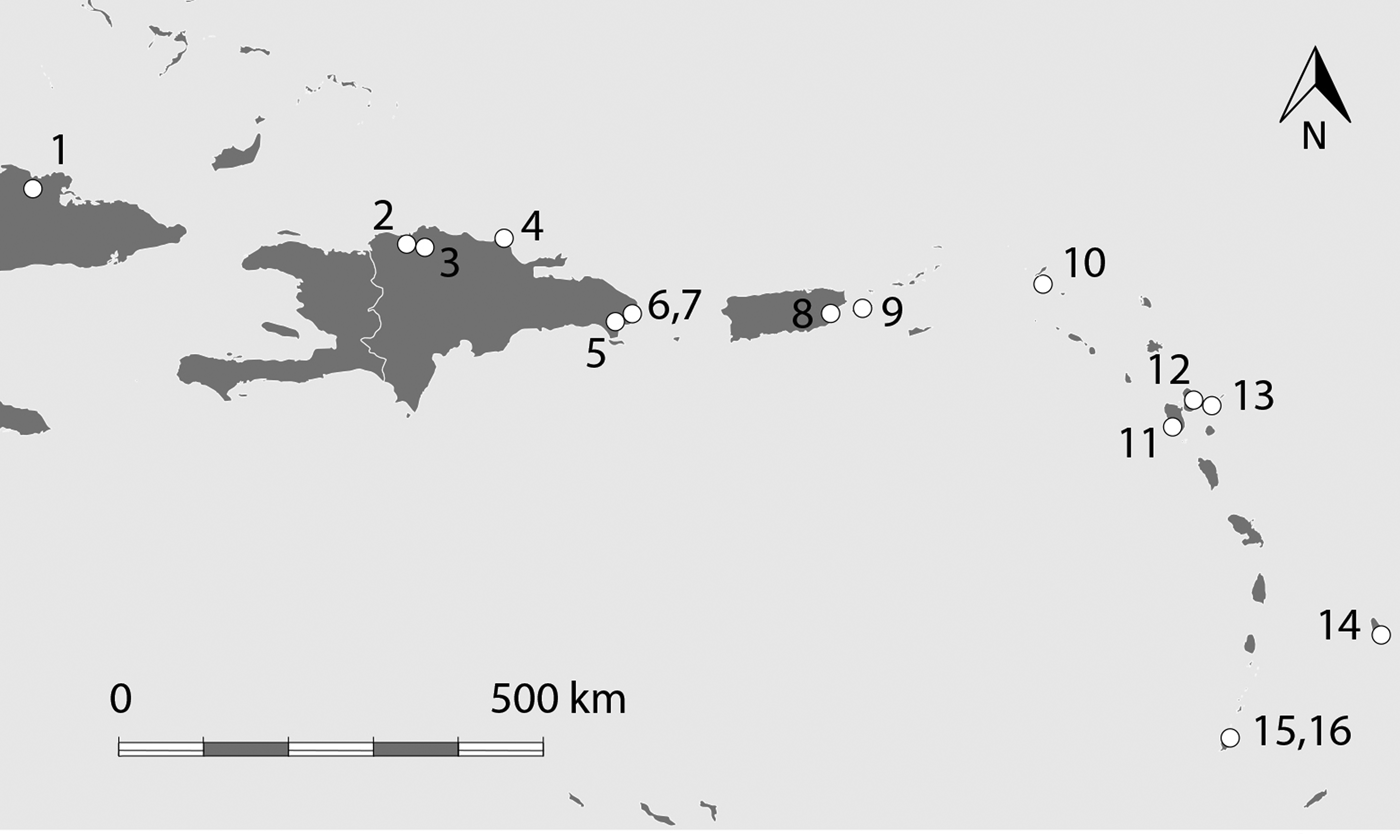

We also compared C. familiaris isotope values from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Saint-Martin, Guadeloupe, Barbados, and Grenada (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 1) according to five criteria: local versus nonlocal, Early Ceramic (500 BC–AD 600) versus Late Ceramic Ages (AD 600–1500/1600), buried versus nonburied individuals, Greater versus Lesser Antillean, and modified (e.g., pendants) versus unmodified remains. Where applicable, published morphometric data permitted comparisons between, diet, localness, and morphology. Additionally, a dietary mixing model was applied to four buried dogs, providing a detailed biography of these individuals. Estimated withers heights provide morphological evidence for the existence of two native “breeds” of dogs; details regarding FRUITS mixing models are further addressed in the online supplement (Supplemental Text 1).

Figure 1. Map of precolumbian sites from which samples were acquired. (1) Cueva Belica, Cuba; (2) El Flaco, Dominican Republic (D.R.); (3) El Carril, D.R.; (4) Playa Grande, D.R.; (5) Cueva de Berna, D.R.; (6) El Cabo, D.R.; (7) Manantial de Cabo san Rafael, D.R.; (8) Punta Candelero, Puerto Rico; (9) Sorcé, Vieques; (10) Hope Estate, Saint-Martin; (11) Cathédrale de Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe; (12) Morel, Guadeloupe; (13) Anse à la Gourde, Guadeloupe; (14) Silver Sands, Barbados; (15) La Poterie, Grenada; (16) Pearls, Grenada.

A total of 81 teeth and 24 bone collagen samples of C. familiaris were sourced from precolumbian sites throughout the Caribbean, including from a dog burial at El Flaco (Supplemental Table 1), and were analyzed by Shev (Reference Shev2018). Methods of stable isotope analysis, morphometric analysis, and FRUITS dietary mixing models are published extensively elsewhere and are presented online (Supplemental Text 1).

Results

Withers Height

Withers height was estimated for dogs from El Flaco (n = 2) and was added to Grouard and coauthors’ (Reference Grouard, Perdikaris and Debue2013) data (Supplemental Table 2).

Collagen Isotope Data

In total, 21 samples yielded high-quality collagen. An overlap in isotope values can be observed in all parameters of examination (Figure 2a). Further details on sample conditions and results are provided in the online supplement (Supplemental Text 1).

Figure 2. (a) Bivariate plot of dog δ15N and δ13C values from El Flaco and El Carril, Dominican Republic; Morel and Cathédrale de Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe; and Hope Estate, Saint-Martin (Shev Reference Shev2018); (b) chart showing the estimated bioavailable 87Sr/86Sr local ranges (represented by boxes) of each site/island and whether each sample fits into or outside these ranges.

Enamel Isotope Data

Local versus Nonlocal

Thirteen of 50 samples possess strontium isotope ratios interpreted as nonlocal (Figure 2b) and showed relative enrichment in δ13Cen values (local, μ = −11.26‰, Mdn = −11.28‰; nonlocal, μ = −10.66‰, Mdn = −10.99‰). The Greater Antillean nonlocal δ13Cen mean value was 0.61‰ higher than in locals; in the Lesser Antilles the nonlocal δ13Cen value was 0.7‰ higher (Figure 3a). A t-test confirmed a significant difference in means (t = 2.2638, p = 0.029079). Excluding outliers larger than one standard deviation (critical t = 2.0484, p = 0.021275) also demonstrated significant differences. Details regarding limitations in Caribbean isoscapes are available online (Supplemental Text 1).

Figure 3. (a) Box plot showing median δ13Cen values (horizontal line), inner quartiles (box), value ranges (whiskers), and outliers (dots) for all comparative parameters; (b) FRUITS dietary mixing model results for El Flaco (FND 2270), Morel (FND 2727 and FND2729), and Cathédrale de Basse-Terre (CBT5002).

Burials versus Nonburials

δ13Cen values were available for 16 buried and 28 nonburied dogs, showing broad similarities between groups (burials, μ = −10.86‰, Mdn = −10.99‰; nonburials, μ = −11.07‰, Mdn = −11.17‰) and demonstrating no significant dietary differences between buried individuals and those that were not. There was no correlation between localness and the propensity for burial: 21.4% of buried and 26.7% of nonburied individuals were nonlocal.

Greater versus Lesser Antilles

Diets of dogs from the Greater (n = 48) and Lesser Antilles (n = 25) were similar (G. Antilles, δ13Cen μ = −11.11‰, L. Antilles, δ13Cen μ = −10.88‰; G. Antilles, Mdn = −11.17‰, L. Antilles, Mdn = −11.07‰). Given the disparity in sample numbers between the two regions, we ran a t-test (critical t = 1.9939, p = 0.33867), which confirmed there was no significant difference in mean values.

Early (500 BC–AD 600) versus Late Ceramic Age (AD 500/600–1500)

There were no significant differences in means (Early, δ13Cen μ = −10.83‰; Late, δ13Cen μ = −11.12‰). Both groups demonstrated considerable overlap.

Modified versus Unmodified

No dietary differences were observed between modified (n = 22) and unmodified remains (n = 44). Both groups exhibited similar values (modified, δ13Cen μ = −11.12‰, Mdn = −11.07‰; unmodified, δ13Cen μ = −10.98‰, Mdn = −11.08‰). The vast majority of modified remains (n = 22, 95.7%) were nonlocal, with the exception of a perforated canine from Manantial del Cabo de San Rafael (87Sr/86Sr = 0.7092, local range = 0.70914–0.70924).

Dietary Mixing Models

The results of the FRUITS modeling are presented in Figure 3b and Table 1 (see also Supplemental Text 1). They suggest that these dogs mainly consumed plants foods with modest amounts of C4 plants (likely maize), possibly indicating intentional feeding. Of these, the two nonlocal dogs (FL FND2270 and MO FND2729) exhibited relatively higher proportions of marine protein consumption.

Table 1. Dietary Estimates (%) for Four Caribbean Dog Specimens Derived from the FRUITS Dietary Mixing Model.

Discussion

We found overlapping mean values in four of the five comparative parameters. The values are similar to those of humans from the region, likely reflecting broad-spectrum diets comprised of C3 plants supplemented with C4 crops, as well as terrestrial and marine proteins (Laffoon et al. Reference Laffoon, Hoogland, Davies and Hofman2019; Pestle and Laffoon Reference Pestle and Laffoon2018). These data suggest that dogs are an effective isotopic surrogate in the precolumbian Caribbean.

The only significant difference in mean δ13C values that we found is between nonlocals and locals. Of all samples (n = 49), 22.4% were deemed nonlocal. They likely either migrated alongside humans to new locations or were exchanged between different human groups. Similar mobility patterns have been suggested for Anse à la Gourde and Morel, where 30% of studied dogs were nonlocal (Laffoon et al. Reference Laffoon, Esther Plomp, Davies, Hoogland and Hofman2015, Reference Laffoon, Hoogland, Davies and Hofman2019; Plomp Reference Plomp2013).

Ethnographies of indigenous peoples from the South American lowlands provide insight into how dogs may have been treated in the past (see Koster Reference Koster2009). The exchange of hunting dogs by renowned dog breeders such as the Waiwái of Guyana and Brazil (Howard Reference Howard2001:248) may serve as a useful analogy. Ethnohistoric sources describe the use of dogs in Hispaniola as valued hunting aids, although it is possible that dogs were also a food source (Las Casas Reference Las Casas1876 [1561]:341). However, given the sparse evidence of butchery or cooking, the consumption of dogs may have been restricted to times of food scarcity (Wing Reference Wing, Reitz, Margaret Scarry and Scudder2008). It is unlikely that dogs were traded as food; it is more probable that they were migratory companions or prized dogs exchanged between communities.

One nonlocal specimen from El Carril (FND 30) had an 87Sr/86Sr ratio (0.7090) denoting a likely coastal origin. This sample also had the most enriched δ13Cen (−8.8‰) and δ18Oen (−1.8‰) values of any dog from Hispaniola (Shev Reference Shev2018). This individual likely subsisted on a diet rich in marine proteins, with higher oxygen values indicating natal origins in an arid, low-altitude, or coastal region (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhang, Hughes, Zhu, Dong, Ren and Chen2016). Two nonlocal dogs from Silver Sands in Barbados demonstrated similarly high δ13Cen values (−8.8‰ and -8.6‰), whereas one exhibited an 87Sr/86Sr ratio (0.7075) suggesting possible natal origins from a nearby island. According to the FRUITS modeling, two nonlocals (FL FND2270 and MO FND2729) consumed higher proportions of marine proteins, indicating that some individuals that were exchanged or migrated alongside humans were possibly “sea dogs” consuming foods such as pelagic fish.

Conclusion

Broad similarities and trends can be seen in the paleodietary and mobility signatures of dogs analyzed throughout the insular Caribbean, regardless of time period, burial context, and location. At a regional scale, geographic patterning of isotopic values of dogs appears to mirror that of humans for the most part. The most significant disparity in diet occurs between local and nonlocal dogs, which is statistically significant enough to merit consideration. Nonlocal dogs likely received different foods than did locals, perhaps reflecting differences in social value or spatially structured foodways between certain individuals. The findings from the dietary mixing model suggest that the two nonlocals had diets higher in marine protein than the two local dogs; however, more data are needed to accurately assess whether there is a broader correlation between mobility and enriched isotopic values.

Acknowledgments

There are no conflicts of interest regarding the financing of this research or the writing of this article. This research was supported by the NWO PhD in the Humanities grant (Project PGW.18.015), the Island Networks project (NWO grant 360-62-060), and NEXUS 1492 (ERC-Synergy grant 319209). Samples were provided by Roberto Valcarcel Rojas, Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, Miguel Rodríguez López, Menno L. P. Hoogland, Peter L. Drewett, Sophia Perdikaris, Elizabeth S. Wing, the Florida Museum of Natural History, the Museo del Hombre Dominicano, the Service Régional de l'Archéologie de la Guadeloupe, the Barbuda Council, and the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. The study of the dogs from Guadeloupe was supported by the Fyssen Foundation, Ministry of French Culture, and ATM Biodiversité from the MNHN Paris. The study of Barbadian dogs was supported by the Islands of Change (grant 0851727 REU), Office of Polar Programs Arctic Social Sciences Program, and PSC CUNY grants 2005–2008 to Dr. Sophia Perdikaris. Special thanks to Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam for allowing us to use their facilities.

Data Availability Statement

All data resulting from this research are within this article and in the supplemental materials; they are also available in the Easy archive at KNAW/DAN (https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/).

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.58.

Supplemental Text 1. Size estimations, isotopic analysis methodology, FRUITS dietary mixing models, collagen data, Caribbean isoscapes, and enamel data.

Supplemental Table 1. List of C. familiaris Enamel and Collagen Samples and Values from the Insular Caribbean.

Supplemental Table 2. Estimated Height at Withers (WH) from the Total Length (TL) of Long Bones.