Introduction

Education of residents is confronted by several major challenges that are especially acute in lengthy surgical training programs. The volume of information that needs to be mastered is immense, and clinical obligations frequently limit the amount of time that can be devoted to education. It is often difficult to maintain a high degree of engagement in the context of fatigue and frequent clinical distractions. Unlike most other educational environments in which knowledge and experience are relatively uniform across students, residents range from interns who have just finished medical school to chief residents about to go into practice, so it can be difficult to design activities that are appropriate for all levels without being too advanced for the junior residents or too straightforward for the seniors. As a result, formal didactic resident curricula in neurosurgery are rare and generally consist of such traditional techniques as lectures and illustrative case presentations, and much of what must be learned is acquired through independent study.

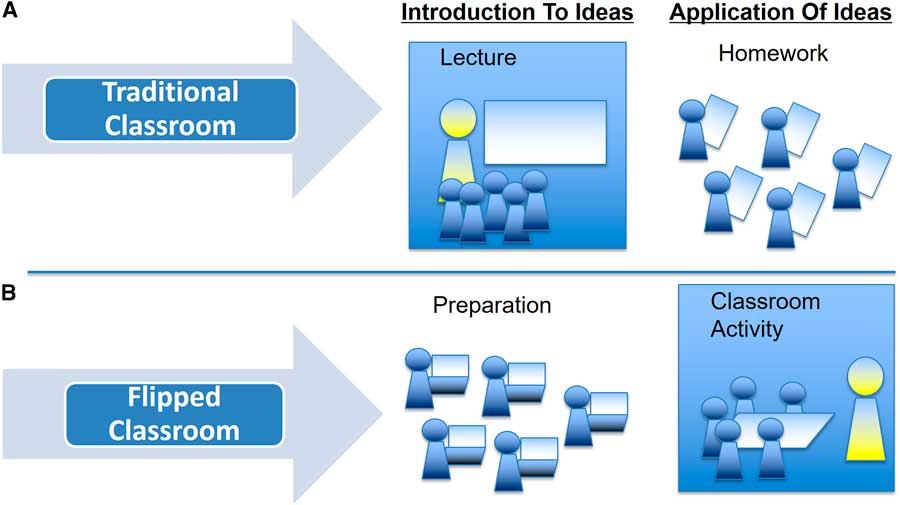

Recent advances in adult learning theory have revolutionized preclinical and clinical training across a number of specialties. According to the philosophies of constructivism and active learning, adult students learn best when able to fit novel concepts into existing conceptual frameworks, allowing each individual to construct his or her own understanding of a topic based on past experience in a self-motivated manner.Reference Cornelius-White and Harbaugh 1 , Reference Gagnon and Collay 2 One strategy to accomplish this is the “flipped classroom,” conceptualized two decades ago by Mazur,Reference Mazur 3 in which students review materials ahead of time in order to maximize the value of in-classroom discussion (Figure 1).Reference Lage, Platt and Treglia 4 In contrast to traditional classroom instruction in which ideas are introduced in lecture form and subsequently applied during homework assignments, the flipped classroom involves introduction to relevant concepts during a self-directed independent study period followed by application of ideas in a facilitator-guided interactive setting. The flipped classroom has recently been applied to many educational settings at the undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate levels,Reference Armour, Schneid and Brandl 5 - Reference Yong, Levy and Lape 17 as well as in such professional fields as pharmacy,Reference Bossaer, Panus, Stewart, Hagemeier and George 18 - Reference Koo, Demps, Farris, Bowman, Panahi and Boyle 21 nursing,Reference Betihavas, Bridgman, Kornhaber and Cross 22 medicine,Reference Belfi, Bartolotta, Giambrone, Davi and Min 23 - Reference Veeramani, Madhugiri and Chand 30 and adult instruction in the workplace,Reference Nederveld and Berge 31 and it has been shown to facilitate the development of effective teamwork and problem-solving skills and improve subsequent contextual recall of practical information. However, these principles have rarely been employed for resident educationReference Tainter, Wong, Cudemus-Deseda and Bittner 32 , Reference Young, Bailey, Guptill, Thorp and Thomas 33 and have never been studied in the context of neurosurgical resident training.

Figure 1 The flipped classroom concept. In the traditional learning environment (A), students are introduced to ideas via a lecture provided by a content expert and subsequently apply those ideas in independent study homework assignments. The flipped classroom (B) involves introduction to ideas prior to a group classroom activity where those ideas are applied in an interactive manner. Note the evolution of the faculty preceptor from the primary disseminator of information (“sage on the stage”) to become a facilitator of knowledge transfer from one resident to another (“guide on the side”).

We hypothesized that a flipped classroom model may have advantages for a surgical residency curriculum, including increased efficiency to maximize use of the limited time outside the operating room and the development of a collaborative and interactive environment to maximize resident engagement. In addition, division of labor across different degrees of complexity makes the activity appropriate for both junior and senior residents, allowing everyone to contribute based on their own level of knowledge and experience. We report the results of implementation of a novel comprehensive neurosurgery resident curriculum based on these ideas.

Methods

Design

We designed a flipped classroom curriculum for all the residents in an academic neurosurgery training program based on 40 weekly mentored discussions. Each discussion is devoted to a single neurosurgical diagnosis based on a list of topics distributed across the field of neurosurgery (see Table 2). Several days prior to each meeting, each resident is randomly assigned a specific question to study in preparation for the session based on their level of experience (see Table 1). Junior residents (postgraduate year [PGY] 1–3) are responsible for learning what each condition is: clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, radiology, pathology, etiology, and epidemiology. Senior residents (PGY 4–5), who already have a basic understanding of the disorders, study when to operate: medical and surgical options, indications and contraindications for surgery, and evidence for intervention. Chief residents nearing proficiency (PGY 6–7) are responsible for knowing how the procedures are performed: surgical technique, complications, side effects, outcome, and follow-up. Each resident is instructed to use their choice of available resources (including textbooks, journal articles, atlases, and online resources) in order to obtain a general understanding of the topic in addition to their assigned question in order to maximize the comprehensiveness of the discussion.

Implementation

The neurosurgical curriculum in place at the time of the transition to the new curriculum had not changed significantly during the seven years prior to implementation and consisted of a set of faculty-prepared lectures accompanied by case discussions. The new curriculum replaced these lectures and mentored case discussions with the new flipped classroom activity. During the in-classroom activity, the residents spent 90 minutes as a group sharing knowledge about what they had learned during preparation by individually discussing the assigned questions in order. Following the initial discussion, the group worked through a number of relevant cases to discuss clinical reasoning and medical/surgical considerations for the topic under discussion, with special emphasis on what had been learned during preparation. A neurosurgical faculty member was present and available to answer questions, but the discussion was encouraged to be resident-led, with minimal direct faculty involvement, and this allowed the residents to effectively educate each other.

Assessment

Some six months after implementation, residents were asked to complete a questionnaire to assess their impressions of the program. The assessment was anonymous except for PGY level (1–3, 4–5, or 6–7). The survey consisted of 14 statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale designed to assess efficacy, clinical utility, relevance, engagement, collaboration, and preparation strategies. Free-text entry was employed to assess the amount of time spent in preparation, what materials were used, and what they did and did not like about the program.

All residents in the program were required to take the primary examination for the American Board of Neurological Surgery. This examination comprises 375 multiple-choice questions covering information on disciplines related to the practice of neurosurgery that approximately cover the spectrum of topics addressed by the curriculum. We assessed the raw score and passage rate for the seven years prior to implementation of the program and during the first year after implementation. Formal statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test or analysis of variance as appropriate to compare survey results and exam performance, using a two-tailed test, with significance defined as a p value of less than 0.05. The study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board.

Results

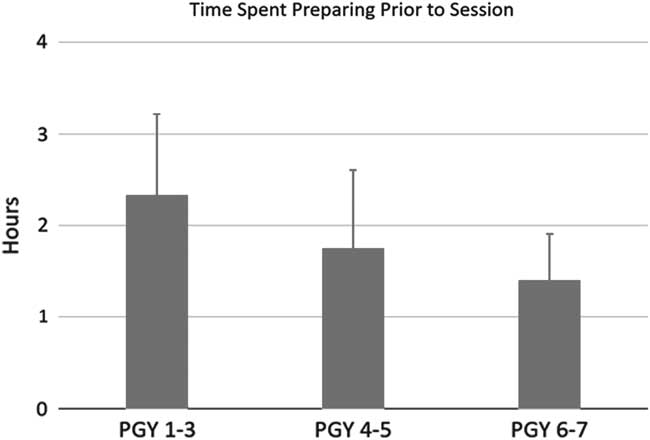

Some 12 residents regularly participated in the program, including 5 junior residents (PGY 1–3), 4 senior residents (PGY 4–5), and 3 chief residents (PGY 6–7). The average time spent in pre-classroom preparation was 1.75±0.40 hours, with chief residents reporting slightly less preparation time and junior residents slightly more preparation time than the average, though this did not achieve statistical significance (Figure 2). The materials used included textbooks (11/12), journal articles from clinical neurosurgery journals (7/12), and online resources (5/12), with the majority (8/12) of residents using more than one resource. Senior residents were more likely than others to report that it was difficult to find time for preparation, although the total preparation time was highest for junior residents. The sessions were incorporated into a series of academic conferences, so that the total amount of time spent on teaching sessions did not change before or after implementation.

Figure 2 Reported time spent in pre-classroom preparation. There was a trend toward less time spent by more senior residents, but the difference did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.68). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

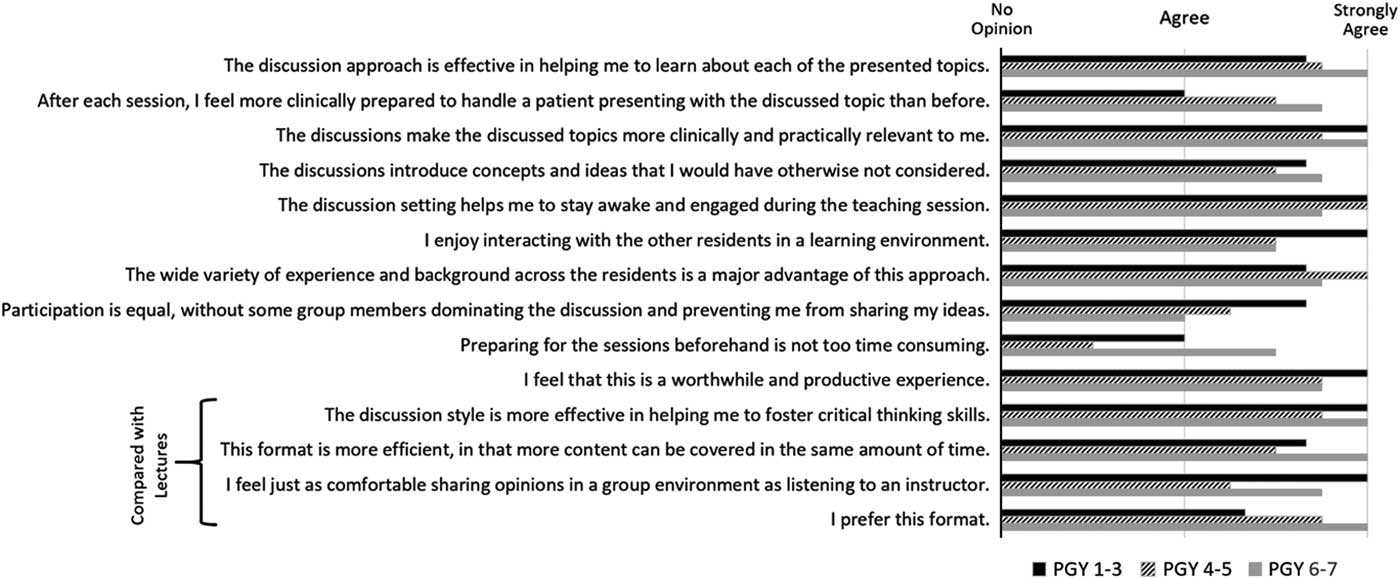

The survey results are shown in Figure 3. All respondents reported that the experience was highly worthwhile and efficient and made them feel more prepared to evaluate and treat patients with conditions that had been discussed using the new teaching format when compared with lectures. Junior residents were slightly less likely to report feeling clinically prepared but more likely to appreciate the interaction with other residents and to feel that the conversation involved equal participation. All residents indicated that the different perspectives provided by the variety of experience levels across seven years of residency was a major advantage of this program, and all indicated that they preferred it to lectures.

Figure 3 Results of 14-question survey. Each question was answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=no opinion, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree). All responses were 3 or higher and are shown according to experience level.

In the free-response part of the survey, participants praised the fact that they were “sharing ideas instead of being supplied with information” and indicated that the format was “highly engaging.” They indicated that distribution of the workload made it possible to “cover more than could be accomplished working independently,” and this led to a “sense of teamwork and camaraderie” as they learned to rely on each other. They enjoyed the “variety of having a different task” to research each week and reported that “retention and general knowledge is improving weekly” as participants became more comfortable with the process. Overall, it was found to be a “great educational experience” and “excellent for junior residents in particular.”

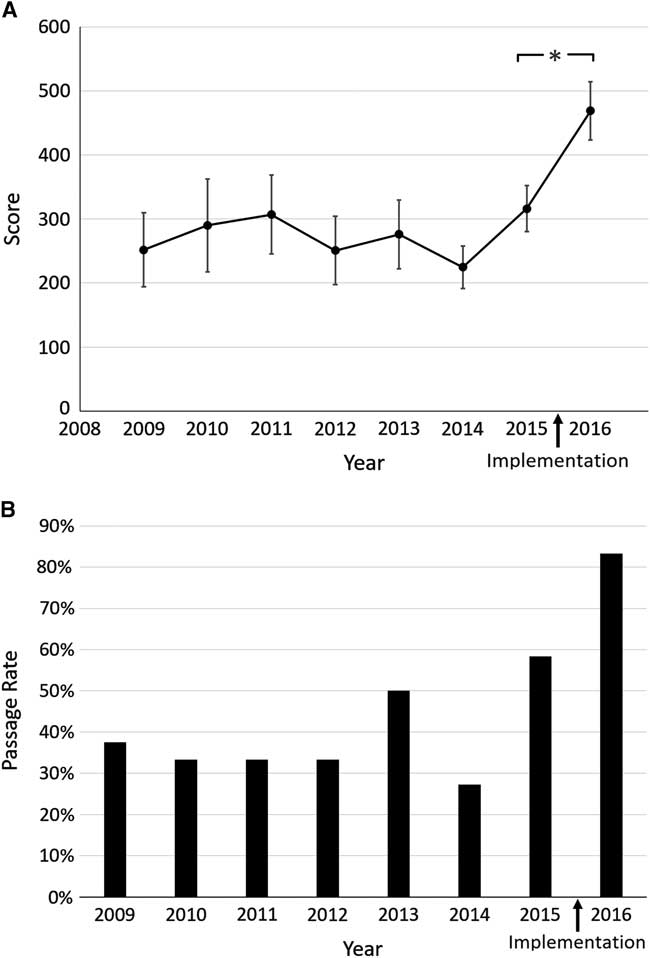

Analysis of the results of the written board examination revealed that the average score increased from 316±36 prior to implementation to 468±45 afterward (Figure 4A), which constituted a significant difference (p<0.05, Student’s t-test) and higher than during any of the prior seven years. Some 83% of residents achieved a passing score on the examination (Fig. 4B). While this did not represent a statistically significant difference compared with the prior year (p=0.2, Fisher’s exact test), it was more than twice the average rate across the prior seven years and the highest rate of passage in more than a decade.

Figure 4 Results of the American Board of Neurological Surgery written examination, which was taken by all participants. (A) Average score on the examination for the seven prior years compared with the year following implementation. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean; *p<0.05. (B) Proportion of residents who achieved a passing score on the board examination for the seven previous years compared with the year following implementation. The passing score is based on performance on a curve compared with all residents who take the exam nationally.

Discussion

Advantages of Flipping the Neurosurgery Classroom

According to the Flipped Learning Network, “flipped learning is a pedagogical approach in which direct instruction moves from the group learning space to the individual learning space, and the resulting group space is transformed into a dynamic, interactive learning environment where the educator guides students as they apply concepts and engage creatively in the subject matter.” 34 These principles have many advantages for resident education compared with traditional instruction techniques involving didactic lectures and case discussions. First, by enlisting the residents in the process of teaching, they become more engaged in the process of learning. Emphasis is placed on collaborative learning, since social interaction allows for continued feedback, deeper engagement, and inquiry-based learning, all of which facilitate active building of knowledge.Reference Cornelius-White and Harbaugh 1 , Reference Gagnon and Collay 2 The flipped learning format also resembles the real-world clinical problem-solving environment, which frequently involves consultation with peers and active discussion among team members, which often reveals a diversity of experiences and approaches.Reference Jacobsen 35 Second, by having each resident study a concept appropriate to his or her level prior to discussion in a collaborative session that involves interaction of all the residents, it is possible to leverage the extensive wealth of experience gained across seven years of resident training. Senior residents are able to impart their familiarity and proficiency in treating neurosurgical disorders to junior residents, while juniors are able to share their understanding of the basic disease processes and topics (such as pathophysiology and pharmacology) that are emphasized in medical school education but which are distant from those nearing the end of residency. Rather than being a limitation, the heterogeneity of experience levels becomes an advantage. Third, assignment to learn specific aspects of each topic encourages utilization of the many excellent neurosurgery educational resources that are available, including textbooks, journal articles, and websites. Learning also becomes personalized to each resident’s needs, preferences, accessibility, and pace,Reference Lage, Platt and Treglia 4 , Reference Mazur, Brown and Jacobsen 36 which allows for greater flexibility and control over the educational experience without requiring strict conformation to one teaching style.Reference McLoughlin and Lee 37 , 38 Finally, efficiency is increased and faculty preparation time reduced compared with preparation of didactic lectures. By shifting the primary transfer of information out of the classroom toward pre-classroom preparation, in-class time is no longer absorbed by didactic instruction, and this creates time for assimilation and application of information.Reference Mazur, Brown and Jacobsen 36 , Reference King 39

Prior Studies of Flipped Instruction

The flipped classroom has been investigated in undergraduate and graduate education in a variety of areas, including mathematics,Reference McCallum, Schultz, Sellke and Spartz 11 , Reference Yong, Levy and Lape 17 business,Reference Balan, Clark and Restall 6 , Reference McCallum, Schultz, Sellke and Spartz 11 statistics,Reference Strayer 14 , Reference Winquist and Carlson 16 chemistry,Reference Gross, Pietri, Anderson, Moyano-Camihort and Graham 8 biology,Reference Galway, Berry and Takaro 7 , Reference Jensen, Kummer and Godoy 10 and computer programming.Reference Mok 12 In each of these contexts, the approach has been associated with a more positive experience and preference over traditional techniques.Reference Galway, Berry and Takaro 7 , Reference Howitt and Pegrum 9 , Reference Moraros, Islam, Yu, Banow and Schindelka 13 , Reference Tune, Sturek and Basile 15 Studies comparing test scores between flipped and traditional formats have shown conflicting results: three reports showed improved scores with flipped teaching,Reference Gross, Pietri, Anderson, Moyano-Camihort and Graham 8 , Reference Tune, Sturek and Basile 15 , Reference Winquist and Carlson 16 two reported no difference,Reference Jensen, Kummer and Godoy 10 , Reference Yong, Levy and Lape 17 and one demonstrated worse performance, though this study reported that students had not been held accountable for pre-classroom preparation.Reference Bossaer, Panus, Stewart, Hagemeier and George 18 There is evidence that some topics might be more appropriate than others for this format. For instance, pharmacology students seem to strongly prefer a traditional lecture format, possibly because of an aversion to the preparation time required to learn mechanisms of action that might be covered more efficiently in a lecture setting.Reference Khanova, McLaughlin, Rhoney, Roth and Harris 19 - Reference Koo, Demps, Farris, Bowman, Panahi and Boyle 21 For medical school education, multiple studies have documented that flipped learning is associated with positive experiences, increased enjoyment, improved learning, and better overall satisfaction.Reference Belfi, Bartolotta, Giambrone, Davi and Min 23 - Reference Veeramani, Madhugiri and Chand 30 In addition, of those studies reporting quantitative data in the form of test results, most showed improvements in test scores in the flipped classroom groups,Reference Belfi, Bartolotta, Giambrone, Davi and Min 23 - Reference Gillispie 25 , Reference Liebert, Lin, Mazer, Bereknyei and Lau 27 , Reference O’Connor, Fried and McNulty 29 , Reference Veeramani, Madhugiri and Chand 30 while others found no difference.Reference Heitz, Prusakowski, Willis and Franck 26 , Reference Morgan, McLean, Chapman, Fitzgerald, Yousuf and Hammoud 28

In contrast to undergraduate and graduate education, studies investigating the impact of flipped learning in resident education are scarce but have generally documented good results.Reference Tainter, Wong, Cudemus-Deseda and Bittner 32 , Reference Young, Bailey, Guptill, Thorp and Thomas 33 One studyReference Tainter, Wong, Cudemus-Deseda and Bittner 32 of residents rotating through the intensive care unit demonstrated that flipped instruction was associated with significant improvement in scores of knowledge, confidence, perceived usefulness, and likelihood of skill use across several demographic subgroups and self-identified learning styles. In another study of emergency medicine residents,Reference Young, Bailey, Guptill, Thorp and Thomas 33 the vast majority of participants preferred the format to traditional lectures and felt that the flipped format added to their knowledge.

In spite of its advantages, several criticisms of the flipped learning model have been raised, including the difficulty in accessing pre-classroom preparation materials, the inability to ask questions when viewing material outside of class, and a tendency to become distracted when having to learn content in a less formal environment, as opposed to having the information given to them in a lecture.Reference Mazur, Brown and Jacobsen 36 Another criticism is that the reported positive effects may be due to the incorporation of active learning rather than the order of group discussion in relation to independent study. In a well-controlled experiment by Jensen et al,Reference Jensen, Kummer and Godoy 10 some 108 undergraduate biology students were divided into two groups, one that completed a critical-thinking assignment prior to group discussion and another that reversed this order, and no statistically significant differences were found in test scores, student attitudes, or gains in scientific reasoning ability. It is possible that there are advantages to initial introduction to principles in independent study rather than in a group environment, but this has not been formally studied.

Present Experience with Flipped Learning

Our program differs from the classically described flipped classroom in two important ways. First, we employed a strategy of division of labor to focus efforts along individually assigned questions rather than having all participants learn the same thing.Reference Lage, Platt and Treglia 4 The purpose of this was to facilitate an environment in which residents rely on each other’s expertise and are accountable for acquisition of specific knowledge. The assignment of a different question to each participant requires that everyone involved prepare and participate, so that each participant becomes responsible for the experience of the group as a whole. Second, rather than providing predefined materials to review (such as a video),Reference Lage, Platt and Treglia 4 participants were free to use their own preferred resources to answer their assigned question. The unrestricted use of available resources not only ameliorated the discomfort associated with new learning methodsReference Hutchings and Quinney 40 but also increased the breadth of potential classroom contributions to include a variety of knowledge sources and encouraged participants to share those resources that were most helpful.

Consistent with previous studies in other disciplines, we found that a flipped classroom format was strongly preferred to traditional teaching methods, that participants felt that knowledge retention was improved compared with that in the conventional environment, and that test scores significantly improved after implementation. Because neurosurgery residents include individuals with a wide variation of skills and experience, we were also able to differentiate results based on resident level, and the results of our study provide unique insight into how residents with different experience levels approach educational activities. We found that the increase in clinical confidence after each session was related to experience level, with junior residents expressing less of an impact than seniors. Conversely, junior residents were more likely to prefer the interactive environment and report satisfaction with the format. Interestingly, midlevel residents were the most likely to feel that preparation was too time-consuming, even though they spent less time on average than their more junior residents, which may be a result of different expectations across experience levels for how much time should be required for an activity like this. Residents at all levels tended not to feel intimidated in the group setting and approved of division of labor as a method for maximizing yield with minimal individual effort. Topics were thought to appropriately cover the field, and assignments were felt to be of appropriate complexity. Scores on the board examination and the passage rate dramatically improved for residents of all levels after implementation of the program, which suggests that the curriculum is associated with improved knowledge of neurosurgical principles using an objective and validated assessment tool.

Limitations

There are several important limitations to this study. First, since the analysis is retrospective and observational using historical controls, it is possible that factors other than the curriculum may have contributed to the observed improvement in test performance and learner satisfaction, although the fact that no other concurrent changes were made to the training program make this less likely. Second, the survey we designed is subjective, designed primarily to gauge attitudes about the program, and has not been validated in other contexts. Third, the sample size is very small, so that variance among individual residents may have confounded the overall results. Fourth, there is a minor trend toward improvement in board scores that preceded the study, and only one year of data after implementation is available to us, so that, even though significant, these data cannot be considered definitive. Finally, although total in-class time did not change, participants in the new curriculum were required to spend more time in independent preparation, and this might have contributed to improved performance.

Conclusions

The flipped classroom is a viable approach to resident education that is positively viewed, engaging, and associated with improvements in test performance. The benefits of the flipped method are likely due to facilitation of active learning, where students take responsibility for acquiring knowledge and are held accountable for applying that knowledge in a group setting. Although larger studies are needed to quantify the impact of this technique across other specialties, our data suggest that the approach offers a promising and pragmatic alternative to didactic resident education that may be associated with improved knowledge and enhanced board performance.

Table 1 Each resident is randomly assigned to research one of the topics for the subject being discussed that week

Table 2 Subjects in clinical neurosurgery (some 40 distinct topic areas were defined that cover the spectrum of neurosurgical diagnoses, each topic area was the basis for an individual discussion session)

Disclosures

Fady Girgis and Jonathan Miller hereby declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose, and that no portion of this work has been presented previously.