Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is gaining in importance as an expression of an organization's commitment to ethical and socially responsible behavior (Du, Bhattacharya, & Sen, Reference Du, Bhattacharya and Sen2007; Teixeira, Ferreira, Correia, & Lima, Reference Teixeira, Ferreira, Correia and Lima2018). For businesses, CSR has been shown to be a potential source of competitive advantage (Porter & Kramer, Reference Porter and Kramer2006; Smirnova, Reference Smirnova2012). Multinational organizations have incorporated CSR in developed as well as developing economies. For instance, Vietnam, one of the fastest growing economies in Asia and Asia Pacific region (Dang, Reference Dang2019), has experienced a remarkable influx of foreign organizations implementing CSR in their local business units (e.g., Intel Products, Unilever, HSBC, Honda, Toyota). CSR could bring about higher firm value and profitability (Harjoto & Laksmana, Reference Harjoto and Laksmana2018; López-Pérez, Melero, & Javier Sese, Reference López-Pérez, Melero and Javier Sese2017) and impact customer loyalty and buying behavior (Cho & Lee, Reference Cho and Lee2019; Du, Bhattacharya, & Sen, Reference Du, Bhattacharya and Sen2007), firm reputation (Schwaiger, Reference Schwaiger2004), and community acceptance (Cho & Lee, Reference Cho and Lee2019).

The conceptions of CSR are rooted in stakeholder theory which spells that a firm as a system of stakeholders, including community and society, has moral obligations to benefit all stakeholders (Carroll, Reference Carroll1991; Clarkson, Reference Clarkson1995; Freeman, Reference Freeman1984). Stakeholder theory also provides a framework for responsible and ethical behavior of businesses toward society (Clarkson, Reference Clarkson1995; Mele, Reference Mele, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2009). From a practical perspective, the theory serves as a normative reference for managers to engage in socially responsible activities and moral decision-making (Clarkson Center for Business Ethics, 1999).

Studies have shown that the attitudes of management have a significant impact on CSR outcomes. Supervisor commitment was found to predict CSR engagement (Muller & Kolk, Reference Muller and Kolk2010; Weaver, Treviño, & Cochran, Reference Weaver, Treviño and Cochran1999a, Reference Weaver, Treviño and Cochran1999b) while visionary leadership was associated with employee efforts in enhancing firm performance (Sully de Luque, Washburn, Waldman, & House, Reference Sully de Luque, Washburn, Waldman and House2008). Supervisors' commitment to ethics was a moderator in the CSR–outcome relationship (Muller & Kolk, Reference Muller and Kolk2010). Kerse (Reference Kerse2019) and De Hoogh and Den Hartog (Reference De Hoogh and Den Hartog2008) found positive correlations between corporate effectiveness and ethical leadership. Metcalf and Benn (Reference Metcalf and Benn2013) established that leadership is crucial in fitting the organization into the wider complex environment to bring about changes and sustainability.

Notwithstanding the importance of managers, understanding business student attitudes towards CSR is vital because business students are tomorrow's business leaders and managers (Albaum & Peterson, Reference Albaum and Peterson2006; Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, & McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017). Attitudes are important because according to Ajzen's (Reference Ajzen1991) Theory of Planned Behavior, intent is a key predictor of future behavior and attitude is a major influencer of related behavior (Dawkins, Jamali, Karam, Lin, & Zhao, Reference Dawkins, Jamali, Karam, Lin and Zhao2014; Pietiläinen, Reference Pietiläinen2015). An organization's ethical posture could thus be foretold by business student attitudes toward CSR (Albaum & Peterson, Reference Albaum and Peterson2006; Ham, Pap, & Stimac, Reference Ham, Pap and Stimac2019). A better understanding of business students' CSR attitudes is necessary to allow learning and socialization actions to be taken in advance to encourage positive socially responsible behavior through curriculum design and to improve student placement through deeper awareness of the expectations of CSR-centric organizations (Ham, Pap, & Stimac, Reference Ham, Pap and Stimac2019; Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk, & Henkel, Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010).

In a comprehensive review of CSR, Aguinis and Glavas (Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012: 953) highlighted a knowledge gap on the underlying mechanisms that link CSR and outcomes, particularly for individuals who ‘actually strategize, make decisions, and execute CSR initiatives.’ There is, therefore, a need for ‘a better understanding of the predictors that influence individuals to carry out CSR activities.’ Most studies on business students have drawn from Forsyth's (Reference Forsyth1980) personal moral philosophy model and used ethical ideologies as predictors of CSR attitudes. Results, however, were mixed. For instance, Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) found positive CSR–idealism and negative CSR–relativism relationships, whereas Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999) reported positive associations between CSR and both idealism and relativism. Studies have also used different predictor variables. Ng and Burke (Reference Ng and Burke2010) examined variables such as individualism, collectivism, personal values, and leadership styles while Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, and Rodriguez-Pomeda (Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015) included job experience, year of study, and nationality.

Though CSR is increasingly practiced globally, the proliferation is not matched by the understanding of business students' CSR attitudes across different contexts. The extant CSR literature on business students as subjects is not only limited (Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, & Rodriguez-Pomeda, Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015) but also heavily based on western contexts such as the United States (e.g., Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Ng & Burke, Reference Ng and Burke2010; Sleeper, Schneider, Weber, & Weber, Reference Sleeper, Schneider, Weber and Weber2006) and Europe (e.g., Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, & Rodriguez-Pomeda, Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015; Ham, Pap, & Stimac, Reference Ham, Pap and Stimac2019). Calls have been made to conduct more studies across different contexts to deepen our understanding of CSR and the extent of transferability of current models and results (Davidson, Reference Davidson and Örtenblad2016; Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2008).

From a values perspective, culture can affect perceptions on ethics and social responsibility (Etheredge, Reference Etheredge1999; Nguyen, Bensemann, & Kelly, Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018). Studying Chinese employees, Zhao, Lee, and Moon (Reference Zhao, Lee and Moon2019) established that collectivism, a characteristic of country culture, moderated employees' CSR perception on organizational identification. Wei, Egri, and Yeh-Yun Lin (Reference Wei, Egri and Yeh-Yun Lin2014) found differences in employee commitment to CSR practices between Taiwan and Canada. Such studies suggest that individuals with cultural backgrounds influenced by collectivist or Confucian values might perceive CSR differently from their western counterparts. Understanding country and cultural contexts is thus necessary to derive better outcomes as CSR is increasingly rolled out in developing countries with different social and cultural norms from the west.

Studies that attempted to address the knowledge gaps on individual-level impacts on CSR, non-western contexts, cultural sensitivity, and attitudes of business students as future managers have tended to address the gaps singly or partially. Studies examining individual-level impacts such as Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, and McKinnon (Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017), Zhao, Lee, and Moon (Reference Zhao, Lee and Moon2019), Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999), Shafer, Fukukawa, and Lee (Reference Shafer, Fukukawa and Lee2007), and Axinn, Blair, Heorhiadi, and Thach (Reference Axinn, Blair, Heorhiadi and Thach2004) have included cultural and social aspects in non-western settings but did not use business students as study subjects of future managers. While Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, and Rodriguez-Pomeda (Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015), Ham, Pap, and Stimac (Reference Ham, Pap and Stimac2019), Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010), and Ng and Burke (Reference Ng and Burke2010) sampled business students, they did so in western settings.

Our paper addresses the intersection of the knowledge gaps and represents one of the first studies to rigorously examine the CSR attitudes of business students in the Vietnam context. By identifying the predictors affecting the CSR attitudes of Vietnamese business students, the paper contributes to the literature by adding to the understanding of how business students perceive CSR in a non-western setting and closing the knowledge gap in CSR research on the micro, individual level of analysis. The paper also enriches the literature by comparing the results between Vietnam and other countries, both western and non-western. The context of Vietnam also contributes as a valuable research setting on both economic and cultural fronts. As Vietnam integrates with the international trade community (e.g., by joining World Trade organization in 2006, Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement in 2016, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in 2020), more and more Vietnamese organizations are emphasizing CSR to foster greater business sustainability amid a fiercer competitive environment (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2013). Vietnamese organizations, embracing export-oriented industrialization, are also facing an urgency to manage CSR effectively as the thriving economy and increased exports have led foreign customers and investors to exert greater scrutiny on CSR practices in Vietnam (Kabir & Thai, Reference Kabir and Thai2017; Newman, Rand, Tarp, & Trifkovic, Reference Newman, Rand, Tarp and Trifkovic2018). Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnam represents one of the few countries in the world that not only avoided an economic recession but also registered a positive growth (of 1.8%) in GDP in 2020 (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2020).

Vietnam culture is a blend of socialist, collectivist, and Confucian elements (Nguyen, Bensemann, & Kelly, Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018). Although studies have addressed CSR in similar economic and cultural contexts (e.g., Lin & Liu, Reference Lin and Liu2019; Zhao, Lee, & Moon, Reference Zhao, Lee and Moon2019), the literature does not reveal any study that examined these contexts on business student attitudes. Our findings will enrich the literature and provide insights for economies with similar cultural contexts and economic aspirations. Our findings also serve to provide valuable information on future CSR managers that Vietnamese organizations and potential investors could use to enhance hiring strategies and assimilation programs to bring about more desirable CSR outcomes. Education institutions can also use the findings as a basis to improve curriculum, enrich student engagement, and sharpen career counseling.

Literature review

Background and theoretical foundations

CSR portrays how an organization views their responsibilities toward social, environmental, and economic impacts of its practices beyond financial gains. CSR can be expressed in several ways. Waddock (Reference Waddock2004) defined CSR as a collection of organizational responsibilities related to the voluntary relationships with multiple stakeholders of the organization. Stakeholders, according to Freeman (Reference Freeman1984: 49), are ‘groups who can affect or are affected by the achievement of an organization's purpose,’ and include government, shareholders, employees, suppliers, customers, environmental activists, and other related parties. Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010: 169) defined CSR as ‘an organization's ethical duty, beyond its legal regulations and fiduciary obligation to shareholders, to sensitively consider and effectively manage its impact on its internal and external relationships and environments.’ Sheehy (Reference Sheehy2015: 643) stated CSR as a form of organizational self-regulation of harms and public good. For the purpose of this study, Kolodinsky et al.'s (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) definition was employed.

The core ideas of CSR are drawn from theories such as Corporate Social Performance, Shareholder Value Theory, and Stakeholder Theory, of which Stakeholder Theory is the most referenced theory in CSR studies (Glavas & Kelley, Reference Glavas and Kelley2014; Lee, Park, & Lee, Reference Lee, Park and Lee2013; Mele, Reference Mele, Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon and Siegel2009). In Stakeholder Theory, the firm is a system of stakeholders operating within the larger societal system providing legal and market infrastructure for the firm whose purpose is to create wealth or value for all of its stakeholders (Clarkson, Reference Clarkson1995). The theory also serves as a normative standard for organizations and managers on ethical and socially responsible behavior. Management is a critical element of CSR because of the responsibility for driving CSR programs to ensure the well-being of both internal stakeholders (employees, suppliers, customers) and external stakeholders (community, government, society) and enhance firm value (He, Chen, & Chiang, Reference He, Chen and Chiang2015; Kerse, Reference Kerse2019).

Managerial and leadership attitudes have a significant bearing on ethical and socially responsible behavior and CSR outcomes of an organization (Metcalf & Benn, Reference Metcalf and Benn2013; Muller & Kolk, Reference Muller and Kolk2010). The Theory of Planned Behavior asserts that attitudes form a major component shaping intent that foretells future behavior (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991). From a theoretical perspective, there is a causal link between the ethical judgment of an individual and the individual's actual ethical behavior (Barnett, Bass, & Brown, Reference Barnett, Bass and Brown1994; Jones, Reference Jones1991; Trevino, Reference Trevino1986). Ethical ideology, also known as moral philosophy, has been studied as an important factor of ethical judgment on ethical and moral reasoning (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1980). Ideology, in general, relates to ideas, beliefs, perspectives, and worldviews. A body of studies including Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1981, Reference Forsyth1985, Reference Forsyth1992), Forsyth, Nye, and Kelley (Reference Forsyth, Nye and Kelley1988), and Barnett, Bass, and Brown (Reference Barnett, Bass and Brown1994) have suggested that ethical ideology affects ethical judgment and influences an individual's attitude toward ethics.

Notwithstanding the variety of ethical theories (e.g., teleology, deontology, utilitarianism, rights, virtues), Schlenker and Forsyth (Reference Schlenker and Forsyth1977) and Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1980) suggested a two-dimensional theoretical framework to describe the ethical ideologies that could explain ethical judgment. The first dimension describes the extent to which an individual rejects universal, moral principles in preference for a relativistic posture while the second represents the extent to which an individual emphasizes idealism in moral attitudes and action to produce positive consequences. Based on the two dimensions of idealism and relativity, four ethical perspectives were conceptualized: situationism, absolutism, subjectivism, and exceptionism. Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1980) developed an instrument to measure the ethical ideologies of idealism and relativism. The instrument has been used in many studies relating to ethical ideologies (sometimes termed personal moral philosophies) and ethical attitudes (e.g., Chen, Mujtaba, & Heron, Reference Chen, Mujtaba and Heron2011; Etheredge, Reference Etheredge1999; Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Park, Reference Park2005; Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli, & Kraft, Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996).

CSR in Vietnam

Anecdotally, CSR was introduced in Vietnam in the 1990s by international companies sourcing in Vietnam. The impetus for the emphasis and spread of CSR can be attributed to two factors (Hamm, Reference Hamm2012; Pham, Reference Pham2011). The first is the ‘Doi Moi’ economic reforms in 1986 aimed at bringing Vietnam from a centrally planned economy to a market economy. An open-door policy to allow international companies to set up operations in Vietnam resulted in many companies bringing in their CSR values and requirements. The second factor is Vietnam joining the WTO in 2006 which led the government to formulate new laws and regulations to meet international practices and standards. Laws and regulations on matters such as environmental protection, labor relations, and sustainability development helped to create awareness on CSR and contributed to its proliferation.

After joining WTO, Vietnam witnessed a growth in CSR implementations as Vietnamese organizations engaged with the international trade community that was increasingly focal on corporate accountability and sustainability (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2013). Expectations grew among markets and customers for trading organizations to embrace ethical and socially responsible behavior toward the community and stakeholders. As Vietnam embarked on export-oriented industrialization, the need for Vietnamese organizations to incorporate CSR into their strategies and operations becomes even more crucial to win over foreign investors and customers (Kabir & Thai, Reference Kabir and Thai2017; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Rand, Tarp and Trifkovic2018).

Recognizing CSR as a highly contextual and contingent concept, Nguyen, Bensemann, and Kelly (Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018) developed a conceptual framework that included institutional contextual factors influencing the nature of CSR in Vietnam. They conceptualized three contextual factors, namely, tradition, governance, and modernity, that will interact with the external social context to determine the ‘CSR thinking’ and ‘CSR doing’ of individuals and organizations in countries like Vietnam that has a distinct social, political, economic, and cultural context. At the individual level, they highlighted the vital role played by individuals such as managers and owners in shaping and determining CSR initiatives for the organization, and hence the need to better understand the personal norms, beliefs, and cognitive attitudes of the individual in order to explain CSR in Vietnam. The lack of CSR studies addressing the contextual nature of CSR and individual level of analysis is also underscored in Aguinis and Glavas (Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012) and Frynas and Yamahaki (Reference Frynas and Yamahaki2016).

The more prominent studies of CSR in Vietnam relate to the perception and interpretation of CSR. Pham (Reference Pham2011) investigated CSR perceptions of 32 industry managers and 97 customers. Managers were found to have a more positive perception of CSR compared to customers who were not clear about the purpose and effects of CSR. Le, Lai, and Truong (Reference Le, Lai and Truong2014) employed Carroll's (Reference Carroll1991) pyramid of CSR responsibilities to evaluate the understanding of CSR of managers. In-depth interviews with nine middle managers showed that managers believed that the community expects organizations to contribute to society, especially in alleviating environmental problems. Nguyen and Mai (Reference Nguyen and Mai2020) conducted semi-structured interviews with top executives of six firms to examine how factors such as legal requirements, financial targets, managerial mindset, and competitor actions affect CSR practices and competitive advantage. Data suggested that all factors were significant in influencing the selection of CSR practices. Properly selected CSR practices were deemed to have a positive impact on firm reputation and employee commitment.

CSR attitudes of business students

As prospective managers, business students are studied for their views on ethics and social responsibility (Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, & McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017). Studies that assessed CSR attitudes of business students are concentrated on western contexts over a variety of CSR-related issues. For example, Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) identified the predictors of CSR attitudes of United States (US) business students using two ethical ideology items (idealism and relativism), spirituality and materialism as independent variables. Ng and Burke (Reference Ng and Burke2010) examined effects such as social concern, collectivism, and leadership type on US student attitudes toward sustainability while Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, and Rodriguez-Pomeda (Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015) investigated the impact of gender, work experience, and education level on the attitudes of Spanish undergraduate students toward CSR and shareholder value maximization. Teixeira et al. (Reference Teixeira, Ferreira, Correia and Lima2018) examined the CSR perceptions of Portuguese management and technology students using social-demographic characteristics (age, gender, education qualification, and professional experience). Comparative studies on CSR attitudes across country contexts have typically surveyed working MBA students or practicing managers as subjects. Examples include the comparison between the US and China (Shafer, Fukukawa, & Lee, Reference Shafer, Fukukawa and Lee2007) and between Malaysia, Ukraine, and the US (Axinn et al., Reference Axinn, Blair, Heorhiadi and Thach2004). Collectively, these studies were either western centric or involved study subjects who were practicing managers.

Research on CSR attitudes of Vietnamese business students is very scarce. Existing studies have focused on the perceptions of Vietnamese students on specific aspects of CSR such as business ethics or sustainability rather than on broader CSR themes. Nguyen, Mujtaba, Tran, and Tran (Reference Nguyen, Mujtaba, Tran and Tran2013) used gender, work experience, education, and ethics training to predict the level of ethical maturity in 260 Vietnamese business students and found that all of the predictors were insignificant. Nguyen, Bui, Nguyen, and Nguyen (Reference Nguyen, Bui, Nguyen and Nguyen2015) found that transformational leadership, collectivism, social values, and money power positively influenced business student attitudes toward sustainability. Comparing US and Vietnamese business students, Nguyen and Pham (Reference Nguyen and Pham2015) found that Vietnamese students reported relatively lower attitude scores. Pham, Nguyen, and Favia (Reference Pham, Nguyen and Favia2015) investigated the effects of gender and experience of having taken a business ethical course on attitudes toward business ethics. Le (Reference Le2017) investigated business and engineering students on their personal ethical values and how these values affect their perceptions on professional ethics.

Research hypotheses

The study seeks to identify the predictors of CSR attitudes of business students. According to Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1992), individuals' moral judgments and actions on business practices are shaped by their personal moral philosophies. Accordingly, studies on student business attitudes have applied Forsyth's (Reference Forsyth1980, Reference Forsyth1992) personal moral philosophy model and used ethical ideologies (i.e., idealism, relativism) as predictors (Etheredge, Reference Etheredge1999; Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Park, Reference Park2005; Singhapakdi et al., Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996). Beyond idealism and relativism, several studies have employed different predictors for their respective influence on ethical and socially responsible attitudes. To enrich the understanding of business student attitudes, particularly in the Vietnam context, and be able to compare against the extant literature, other predictors were included in the study: spirituality and materialism (Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010), gender (Arlow, Reference Arlow1991; Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, & McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017; Sleeper et al., Reference Sleeper, Schneider, Weber and Weber2006), and student seniority (Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, & Rodriguez-Pomeda, Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015; Kumar, Reference Kumar1995). The inclusion of a wider set of predictors from different studies also allows for a synthesis of previous results in the literature.

Idealism and relativism (personal moral philosophies)

Idealism and relativism are orthogonal dimensions of personal moral philosophies/ethical ideologies that influence judgments and actions on business. Idealism refers to the extent in which an individual exhibits behavior that avoids doing harm to others and produces beneficial outcomes for others (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1992). Embracing values of care, empathy, altruism, and consideration for others, an idealist is deemed to view CSR positively. A positive relationship between idealism and ethics and social responsibility was established in Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010), Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999), Singhapakdi et al. (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996), and Park (Reference Park2005).

Relativism involves the replacement of universal moral rules with subjective moral judgment based on specific contexts or circumstances in making decisions. A relativist tends to focus on the outcomes of a judgment and associated idiosyncratic evaluation of alternatives to justify the decision or action (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1992). Davis, Andersen, and Curtis (Reference Davis, Andersen and Curtis2001) did not find any relationship between relativism and empathy, emphatic concern and the ability to accept new perspectives. With the rejection of universal moral principles and an outcome-based orientation, a relativist is inclined to view financial performance as the key objective of organizations over ethics and social responsibility. With the exceptions of a few studies (e.g., Chen, Mujtaba, & Heron, Reference Chen, Mujtaba and Heron2011; Etheredge, Reference Etheredge1999), relativism was found to have a negative relationship with perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility, and ethical judgment (Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Singhapakdi et al., Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996; Vitell, Ramos, & Nishihara, Reference Vitell, Ramos and Nishihara2010).

We posit that idealistic students, with their ethical disposition of altruism, care, and empathy, will view CSR positively. Relativistic students, due to their focus on outcomes and skepticism of moral rules, would tend to exhibit a negative view of CSR. We propose the following hypotheses for idealism and relativism.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): For business students, idealism is positively related to CSR where students with higher levels of idealism hold positive attitudes on the importance of ethics and social responsibility in attaining organizational effectiveness.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): For business students, relativism is negatively related to CSR where students with higher levels of relativism hold negative attitudes on the importance of ethics and social responsibility in attaining organizational effectiveness.

Materialism

Materialism refers to a set of values that focuses on wealth, worldly possessions, image, and status, very often at the expense of concern for the well-being of others (Belk, Reference Belk and Kinnear1984: 291; Kasser, Reference Kasser2016). Studies have shown that materialists have reduced connectedness with others, adverse work motivation, and weaker pro-environmental orientation (Hurst et al., Reference Hurst, Dittmar, Bond and Kasser2013; Kasser, Reference Kasser2016). An employee with materialistic values could affect fellow employees and the organization by degrading organizational citizenship behavior and inflating workplace deviance (Deckop, Giacalone, & Jurkiewicz, Reference Deckop, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz2015). Materialists are less concerned about the environmental consequences caused by their consumption habits (Hurst et al., Reference Hurst, Dittmar, Bond and Kasser2013; Tascioglu, Eastman, & Iyer, Reference Tascioglu, Eastman and Iyer2017). The materialist's traits of possessiveness, non-generosity, and envy (Belk, Reference Belk1995) would tend to go against the values of a caring, ethical, and socially sensitive CSR supporter.

Studies have suggested that materialism exists and is growing in emerging economies (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, Reference Burroughs and Rindfleisch2002; Sharma, Reference Sharma2011). Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2012) argued that materialism is particularly relevant in transitional economies like Vietnam due to improving consumer purchase power, availability of material goods, and exposure to global media and modern lifestyles. The impact of materialism on business student attitudes has not been examined in depth in the extant literature. A negative relationship between materialism and ethic and social responsibility was reported in Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010). We posit that materialistic students, who focus on material possessions, would hold negative attitudes toward CSR.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): For business students, materialism is negatively related to CSR, where students with higher levels of materialism will hold negative attitudes on the importance of ethics and social responsibility in attaining organizational effectiveness.

Spirituality

According to Hodge (Reference Hodge2001), spirituality relates to ‘an individual's relationship with God (or perceived Transcendence)’ whereas religion is characterized by a particular set of communal beliefs, practices, and rituals developed by people who shared similar ‘existential experiences of transcendent reality.’ Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (Reference Giacalone and Jurkiewicz2003) define spirituality as ‘the individual's drive to experience transcendence or a deeper meaning in life, through the way in which they live and work.’ Hodge (Reference Hodge2003) stated that spirituality is key in driving how an individual makes decisions, as well as influencing personal development and outlook of life.

Fry (Reference Fry, Giacalone, Jurkiewicz and Dunn2005) stated that heightened workplace spirituality facilitated by leadership can generate value congruence between employees and CSR. Cavanagh (Reference Cavanagh1999) asserted that spirituality could enhance the understanding of business ethics due to their similarities in goals and inspiration. While most have argued for the ‘intuitive’ positive impact of spirituality on ethics and morality, studies have produced mixed results. Baumsteiger, Chenneville, and McGuire (Reference Baumsteiger, Chenneville and McGuire2013) found that spirituality and religiosity were positively associated with idealism, while Ayoun, Rowe, and Yassine (Reference Ayoun, Rowe and Yassine2015) results were inconclusive on the constructive influence of spirituality on business ethics. Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) tested the relationship between CSR and spirituality and did not uncover any significant relationship.

Though socialist Vietnam is officially an atheist country, many of its people are practicing the beliefs and teachings of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism which encourage virtues of benevolence, humanity, and moral uprightness (Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018). As these virtues are compatible with CSR underpinnings, their spiritual influences could have an impact on the CSR attitudes of business students. We posit the following relationship.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): For business students, spirituality is positively related to CSR, where students with higher levels of spirituality will hold positive attitudes on the importance of ethics and social responsibility in attaining organizational effectiveness.

Gender and student seniority

Previous CSR-related research has investigated the effects of personal demographic characteristics. In particular, gender and student seniority (i.e., year of study) have been used as predictors to explain differences in CSR attitudes (Luthar & Karri, Reference Luthar and Karri2005). Studies have employed these characteristics as control variables (e.g., Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) or independent variables in regression modeling (e.g., Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, and McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017; Sleeper et al., Reference Sleeper, Schneider, Weber and Weber2006). Female business students have been found to hold more positive attitudes toward CSR compared to their male counterparts (Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, & Rodriguez-Pomeda, Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015; Arlow, Reference Arlow1991; Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, & McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017; Sleeper et al., Reference Sleeper, Schneider, Weber and Weber2006).

In Vietnam's socio-cultural context, gender roles revolve around males as the predominant leaders and decision-makers within the family unit and society (UNDP Vietnam, 2015). Females are expected to take on mundane domestic duties and leave ‘macro’ matters to the males. With growing education opportunities and foreign influence on gender equality in business and society, it is unclear the extent to which gender would differ in their perceptions on CSR.

Kumar (Reference Kumar1995) reported that students who took ethical-training courses were likely to support social responsibility. Undergraduate students were found to have a lower ethical orientation than graduate students. Ham, Pap, and Stimac (Reference Ham, Pap and Stimac2019) found that students were more likely to exhibit CSR behaviors when they learn more about CSR while Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, and Rodriguez-Pomeda (Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015) reported that upper-level students were more concerned about business ethics and environmental respectability.

Drawing from extant literature, we posit that female business student attitudes are more likely to support ethical and socially responsible behavior relative to male business students. Business students who are more senior (or advanced in their study program) and hence more advanced in their understanding and appreciation of ethical business conduct are more supportive of CSR.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Female business students are more likely to support the role of ethics and social responsibility in attaining organizational effectiveness, compared to their male counterparts.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Senior business students are more likely to support the role of ethics and social responsibility in attaining organizational effectiveness, compared to their junior counterparts.

The hypotheses are shown in the research model in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Research model.

Control variables

In the study, age was used as the control variable. Though Vietnamese students enter university education at different ages, their ethical and moral attitudes should be developed by the time and not be affected by age. Student seniority differences, if any, should be due to the levels of exposure to CSR knowledge, and not age. Control was to assess that variables were not confounded by age.

Data collection and measurement

Data collection

The empirical data to test the hypotheses were collected through a survey targeting undergraduate business students from four public and private Vietnamese universities in southern Vietnam. These universities, located in Ho Chi Minh City and Binh Duong province, can be considered as representative of key centers of education advancement and economic growth in Vietnam. One of the four universities is accredited by ACBSP (Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs), while another is a member university of Vietnam National University (VNU) which is regarded as one of Vietnam's top universities and ranked within the top 1,000 universities in Asia by Times Higher Education (5 Vietnamese schools listed in QS 2017 University Rankings for Asia, 2017). For the remaining two universities, one has been accredited for education quality by the Ministry of Education and Training and is earmarked by the provincial government to be the premier university in Binh Duong province. The last university is recognized for innovation and technology and is popular among students as a modern and progressive university.

Hard-copy questionnaires were administered to 500 students during their class time at the business schools of the target universities. The questionnaire took about 20 min to complete. The administrators of the survey ensured that all administered questionnaires were returned. After removing responses with missing data, a total of 425 responses were usable, giving a response rate of 85%. The final sample comprises 39.1% of male students and 60.9% of female students.

CSR assessment

Instruments have been developed to assess ethics and social responsibility (Etheredge, Reference Etheredge1999; Hunt, Kiecker, & Chonko, Reference Hunt, Kiecker and Chonko1990; Singhapakdi et al. Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996). Singhapakdi et al. (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996) created an instrument to measure the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility (or PRESOR) that has been popularly adopted or adapted to assess an organization's commitment to and support of CSR (Ham, Pap, & Stimac, Reference Ham, Pap and Stimac2019; Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Moyeen & West, Reference Moyeen and West2014; Teixeira et al., Reference Teixeira, Ferreira, Correia and Lima2018).

Singhapakdi et al.'s (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996) instrument comprised a 13-item scale to evaluate perceptions on the importance of ethics and social responsibility in business decisions. The instrument was validated by data from 153 business students in US business schools and found to be reliable in measuring PRESOR. Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999) attempted to refine the PRESOR instrument using data from 233 part-time MBA students and managers in Hong Kong. A different factorial structure for the CSR construct was found from that in Singhapakdi et al. (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996) which was attributed to differences in the cultural settings of the studies.

Measures

In order to conduct modeling, measurement scales were developed for CSR and its predictors. As in Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010), Saxena and Mishra (Reference Saxena and Mishra2017), and Ham, Pap, and Stimac (Reference Ham, Pap and Stimac2019), CSR was measured using Singhapakdi et al.'s (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996) 13-item instrument on the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility (PRESOR) in achieving organizational effectiveness.

The idealism and relativism predictors were measured using Forsyth's (Reference Forsyth1980) scale. The 20-item scale has been used in Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999), Singhapakdi et al. (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996), and Vitell, Ramos, and Nishihara (Reference Vitell, Ramos and Nishihara2010) to measure idealism and relativism. Spirituality was measured using the 6-item scale developed by Hodge (Reference Hodge2003) while Richins and Dawson's (Reference Richins and Dawson1992) 18-item scale was used to measure the materialism predictor. Gender and student seniority were surveyed as categorical variables.

Participants were asked to indicate their responses to the questions using a 5-point Likert scale, with ‘1’ for ‘Strongly Disagree’ and ‘5’ for ‘Strongly Agree.’ To ensure reliability of the questionnaire, the English version of the questionnaire was first translated into Vietnamese by a bilingual faculty member. The researcher who was the subject matter expert on CSR then checked the Vietnamese version for content and translation accuracy. The Vietnamese questionnaire was then tested on 10 business students, where the researcher went through the entire Vietnamese questionnaire with the students to ensure clarity of the questions and content. Modifications were made when there were confusion or ambiguity in the wording or meaning of the question. This approach is similar to that used in Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, and Rodriguez-Pomeda (Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015), Palihawadana, Oghazi, and Liu (Reference Palihawadana, Oghazi and Liu2016), and Zhao, Sum, Qi, Zhang, and Lee (Reference Zhao, Sum, Qi, Zhang and Lee2006).

Analysis

Factor analysis

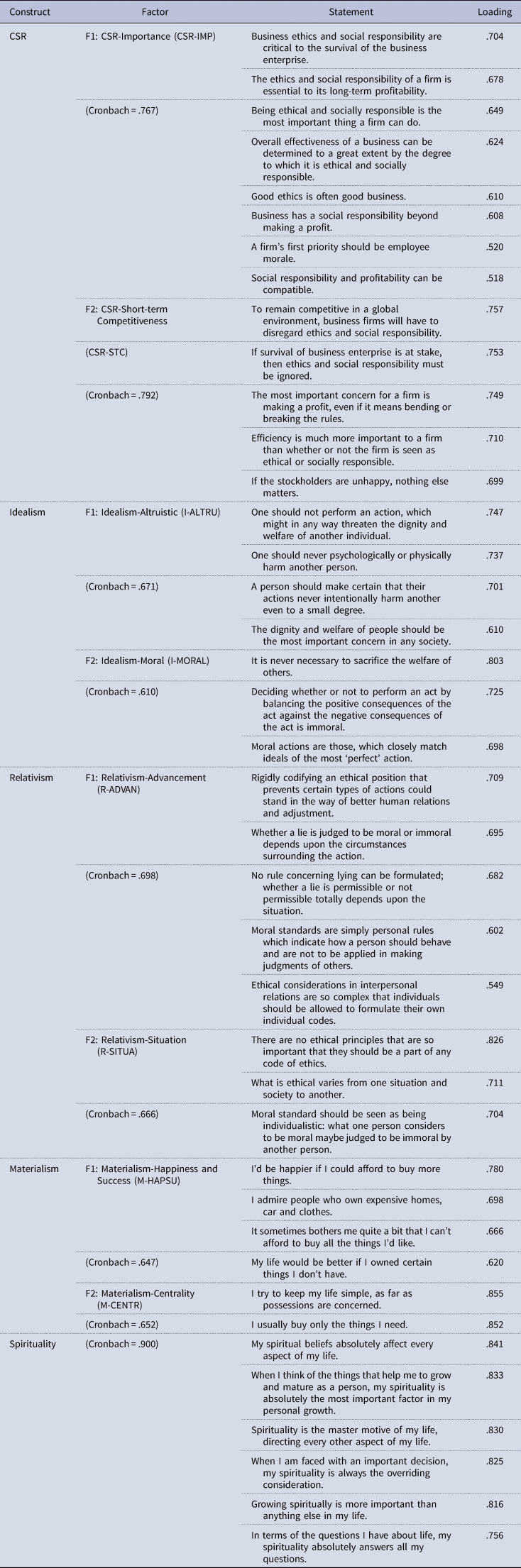

For our sample, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to group similar items into factors and to derive a mathematical model from which the factors were estimated (Field, Reference Field2013: 1949). Results of the exploratory, principle components factor analysis employing a varimax rotation for the CSR and predictor constructs are shown in Table 1. Table 1 presents the items of the factors, factor loadings, and Cronbach's α coefficients for the CSR and predictor constructs. In identifying the factors, loadings for items less than .4 or items with split loadings were removed (Churchill, Reference Churchill1979). Scale reliability was assessed using Cronbach's α reliability coefficient. Table 1 shows that the Cronbach's α coefficients range from .610 to .900. These values are above the minimum threshold level of .5 for acceptable reliability for newly developed constructs (Nunnally, Reference Nunnally1978). Therefore, the items in Table 1 reliably estimate their respective constructs.

Table 1. Factor analysis

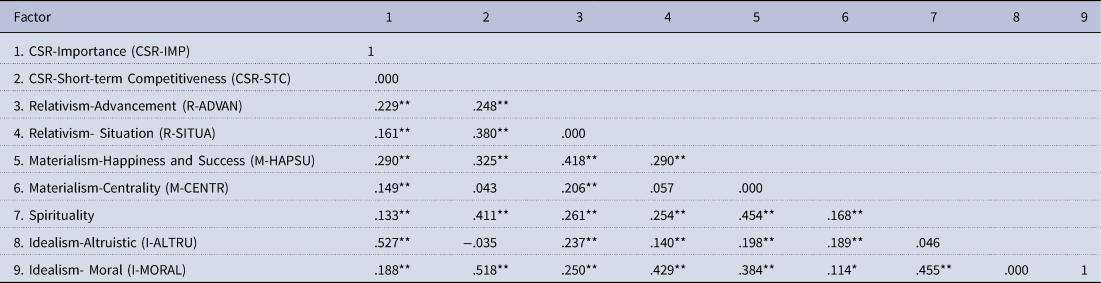

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix for the CSR and predictor factors used to construct the regression models. None of the correlation coefficients in Table 2 is greater than .9, suggesting that multi-collinearity does not appear to be present (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006).

Table 2. Correlation matrix

*p < .05, **p < .01.

EFA yielded a two-factor solution for CSR (Table 1). The factors accounted for 45.2% of the variance. The first factor measures the importance of ethics and social responsibility. As suggested by the top items in the factor, a high score reflects the belief that CSR is important to the long-term survival and profitability of an organization. The factor is named CSR-Importance (CSR-IMP). The second factor, having items in Singhapakdi et al.'s (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996) ‘social responsibility and profitability’ and ‘short-term gains’ factors, is named CSR-Short-Term Competitiveness (CSR-STC) to relate to the role of ethics and social responsibility in achieving short-term gains in profitability, efficiency, and stockholder happiness. In terms of reliability, the Cronbach coefficients for the two factors are .767 and .792, respectively.

The two factors in idealism accounted for 53.6% of the variance. A business student who scores high on the first factor tends to be selfless and other-centric, always acting to benefit and avoiding doing harm to others. The factor is named Idealism-Altruistic (I-ALTRU). The Cronbach coefficient for the items in the factor is .671. The second factor describes the desire to act morally and a behavior that makes decisions aligned with high moral principles and ethical values. The factor, with a Cronbach coefficient of .610, is named Idealism-Moral (I-MORAL).

The two relativism factors accounted for 51.18% of the variance. The first factor depicts a belief that ethical evaluation should not be standardized or controlled so that human relationships and engagement can be improved. A business student with a high score would subscribe to the removal of universal fixed rules and interpretation of morality for the advancement of the human spirit. The factor has a Cronbach coefficient of .698 and is labelled Relativism-Advance (R-ADVAN). The second factor relates to the subjectivity of ethical principles and morality. A high score on this dimension suggests that the business student rejects moral absolutes and believes that ethical evaluation and practices should be situational and based on prevailing circumstances. The factor is termed Relativism-Situation (R-SITUA). The Cronbach coefficient is .666.

The materialism construct had two factors, contributing to 57.29% of the variance. The first factor is labelled Materialism-Happiness and Success (M-HAPSU) and describes the dependence of happiness and success on material possessions. A high score means that the business student believes that acquisition of material possessions will lead to greater happiness and success. The items in the factor produced a Cronbach coefficient of .647. The second factor, comprising reverse-coded items, indicates the general importance of material possessions and acquisitions, with a high score suggesting a business student who attaches centrality to acquiring possessions. The factor is called Materialism-Centrality (M-CENTR). The Cronbach coefficient of the factor items is .652.

The Spirituality construct yielded one factor with a Cronbach coefficient of .900. A business student with a high score on the factor would embrace spirituality beliefs as primarily fundamental in providing direction and motivation in all aspects of life, including the workplace.

Regression models

An assessment was made on the impact of the control variable. Age was found to be insignificant in predicting any of the dependent CSR variables. Regression models showed that age was insignificant at the p < .01 level.

Multiple regression was conducted to analyze the relationships between CSR and the predictors. The regression models for the dependent variables CSR-IMP and CSR-STC are presented in Table 3. The regression results show that the models for both CSR-IMP and CSR-STC are significant at the p < .01 level. The independent variables (predictors) are also significant at the p < .01 or p < .05 levels.

Table 3. Regression models

Table 3 shows that the first factor CSR-IMP (R 2 = .296, Adj.R 2 = .291, F = 59.1, p < .000) is significantly related to I-ALTRU, R-ADVAN, and spirituality. The β values of the three predictors are positive. The second factor, CSR-STC (R 2 = .242, Adj.R 2 = .235, F = 33.571, p < .000), has a negative relationship with M-HAPSU and spirituality. The CSR-STC model also indicates that male students are less prone to support the view that CSR is important for short-term competitiveness. Student seniority was found to be positively associated with CSR-STC, suggesting that senior students tend to support the role of CSR as important in contributing to short-term competitiveness.

Discussion

The study seeks to identify the predictors of business student attitudes toward CSR. Results revealed that underlying dimensions existed within the CSR and several predictor constructs, enabling more specific and precise analysis of the relationships between CSR and the predictors.

Idealism and materialism

Table 3 indicates a positive relationship between CSR-IMP and I-ALTRU (β = .503, p < .01). This finding is similar to that in Singhapakdi et al. (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996), Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999), and Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010). Students who are idealistic and hold an altruistic attitude toward society and others tend to view CSR as an important element in achieving organizational effectiveness. The Vietnam context did not affect the impact of idealism on CSR, suggesting that idealism could be a predictor across cultural contexts. The finding appears to be consistent with the Vietnamese culture of high collectivism as influenced by Confucianism which also advocates empathy, social harmony, and moral uprightness (Low, Reference Low2012; Nguyen, Bensemann, & Kelly, Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018; Shafer, Fukukawa, & Lee, Reference Shafer, Fukukawa and Lee2007). As idealism was found in CSR-IMP only, we conclude that H1 is partially supported.

While no materialism predictors were significant in the CSR-IMP model, M-HAPSU (β = −.156, p < .05) was found to have a negative effect on CSR-STC. A negative relationship between CSR attitude and materialism was established in Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010). Our finding appears to reinforce the idea that dependence of happiness and success on material possessions could influence a materialistic business student to regard CSR negatively as a short-lived effort that does not generate sufficient success and happiness.

Studying the impact of materialism on life satisfaction and standard of living of Vietnamese consumers, Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2013) found that the happiness and centrality dimensions of materialism related negatively to overall life satisfaction and standard of living. The study suggests that materialistic Vietnamese were generally dissatisfied with their lifestyle in their pursuit of possessions. The self-centered focus to accumulate possessions in order to be happy and successful could drive them to socially disengage with friends, family, and society. The negative effect on CSR could arise from a discontented, unhappy life of unfulfilled attainment, leading to a disregard for intrinsic motivations such as empathy and care for others. The impact of CSR-STC could be deemed as temporary and hence unattractive and incapable of satisfying their incessant desire to acquire possessions. As materialism is found to only affect CSR-STC, H3 is partially supported.

Relativism

CSR-IMP was positively related to R-ADVAN (β = .87, p < .05) (Table 3). A positive relationship between CSR and relativism was supported in studies such as Chen, Mujtaba, and Heron (Reference Chen, Mujtaba and Heron2011) and Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999). However, Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) and Vitell, Ramos, and Nishihara (Reference Vitell, Ramos and Nishihara2010) found that CSR was negatively associated with relativism, while Singhapakdi et al. (Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996) did not find any significant relationship between CSR and relativism.

A plausible explanation for the mixed results was provided in Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999) and Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1981) who argued that a relativist, though skeptical on universal moral rules, could accept the importance of ethics and social responsibility but acknowledge situations, such as when survival or competitiveness is under threat, that require ethics and social responsibility to be accorded relatively lower priority. Hence, it is not inconsistent for a relativist to support CSR.

In the Vietnam context, the positive relationship between CSR and relativism could be explained from the cultural perspective. According to Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov (Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010), culture can be expressed in six dimensions, including power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and indulgence. They found that Vietnam scored low on uncertainty avoidance, suggesting that the Vietnamese are more comfortable with ambiguity and less dependent on structured rules and rigid codes. They described people with low uncertainty avoidance scores as those that uphold a more open, casual mindset with reduced attention given to principles than practices. These people tend to rely on informal norms in dealing with most matters. This cultural dimension could account for why students that endorse the principle of ethical and social responsibility could act out the principle through pragmatic adaption to circumstances and flexible compliance to rules and codes.

In developing a conceptual framework for understanding CSR in Vietnam, Nguyen, Bensemann, and Kelly (Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018) highlighted the huge influence of Confucian values on Vietnamese culture. They provided an insight into the positive impact of relativism by noting that the Vietnamese interpretation of one of the Confucian values applicable to CSR conceptualization and implementation is Dieu Do which denotes the virtue of moderating one's stance in the interest of social harmony. This virtue denounces excessively rigid and assertive relativistic behavior and could account for the positive CSR–relativism relationshipFootnote 1.

It is interesting to note that both Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) and Vitell, Ramos, and Nishihara (Reference Vitell, Ramos and Nishihara2010) found negative CSR–relativism relationships using student subjects from western countries (i.e., US and Spain, respectively). Etheredge (Reference Etheredge1999), Chen, Mujtaba, and Heron (Reference Chen, Mujtaba and Heron2011) and this study, which all established a positive CSR–relativism relationship, used student subjects from East Asian countries, namely, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Vietnam respectively. The mixed results could be attributed to differences between the West and East Asia, in aspects such as cultural norms and country characteristics that are manifested in the student attitudes. East Asian culture emphasizes discipline, hard work, placing society before self, and an overarching reverence to authority. Taken together, these attributes could have influenced individuals to adopt a stance where societal benefits (through CSR) are deemed acceptable when delivered in a manner moderated by expectations of superiors or by peculiarities of the situation. Thus, navigating around situations and rules could be appropriate and even essential to pass benefits to society and other stakeholders. As our findings indicated CSR-IMP were positively related to the relativism predictor, H2 is partially rejected.

Spirituality

The regression models in Table 3 reveal that spirituality is significant in both CSR-IMP and CSR-STC. Spirituality related positively to CSR-IMP (β = .87, p < .05) and negatively to CSR-STC (β = −.302, p = .000). The finding of a significant relationship between spirituality and CSR attitudes for business students differs from that in Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010). Our finding represents the first to report a significant effect of spirituality on CSR attitudes in the Vietnam context and provided further evidence to support the literature on the association between spirituality and ethical behavior and understanding (e.g., Baumsteiger, Chenneville, & McGuire, Reference Baumsteiger, Chenneville and McGuire2013; Cavanagh, Reference Cavanagh1999; Fry, Reference Fry, Giacalone, Jurkiewicz and Dunn2005). As the direction for spirituality is different for CSR-IMP and CSR-STC, H4 is partially supported.

The positive impact of spirituality on CSR-IMP could be explained by the relationship between spirituality and religious beliefs in Vietnam. Examining the link between spirituality and CSR from a religious perspective, Vu (Reference Vu2018) outlined the applicability and relevance of high-level Buddhist principles to CSR practice. Buddhist principles such as Middle Path, Cause-Condition-Effect, Noble Eightfold Path, Skilful Approach, and Non-Self advocate ethical, moral, and socially responsible behavior. Buddhism also sought to inspire long-term, sustainable pursuits by underscoring the interconnectedness of the world and exhorting people to contemplate how present actions should be performed to prevent future harm (Vu, Reference Vu2018; Vu & Tran, Reference Vu and Tran2021). Buddhism, being one of the most popular religions, could have influenced the spiritual disposition of the Vietnamese to support the CSR-IMP.

The negative relationship between spirituality and CSR-STC could be explained by business students' spiritual alignment with the Buddhism principle on karma, defined as an action with an intent leading to future consequences. Even as Buddhism encourages long-lasting perspectives, it cautions against the karmic consequences of actions, such as practices that are short-lived that could harm the future. Applying Buddhist principles to CSR, Vu (Reference Vu2018) highlighted that ‘short-term pursuits and the instrumentalization of CSR in discounting the future can result in karmic consequences.’ According to Vu and Tran (Reference Vu and Tran2021), karma rationalizes the consequences of actions, encourages long-term over short-term survival pursuits, and endorses leadership and organizational approaches to sustainability. Though stated in general terms, these principles could have shaped the attitudes of spiritual business students as future business leaders to form a negative view of short-term business pursuits. In Thailand which is primarily a Buddhist country, Buddhist principles alluding to long-term sustainability have been developed into a formal framework of business and leadership practices where avoidance of short-term profitability is highlighted as a highly desirable leadership practice (Suriyankietkaew & Kantamara, Reference Suriyankietkaew and Kantamara2019).

Gender and student seniority

Table 3 indicates that male students compared to their female counterparts were found to hold negative views on CSR-STC (β = −.279, p < .01). Past studies (e.g., Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, & McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017; Lämsä, Vehkaperä, & Puttonen, Reference Lämsä, Vehkaperä, Puttonen and Pesonen2008; Sleeper et al., Reference Sleeper, Schneider, Weber and Weber2006) had reported female students exhibiting more favorable attitudes toward CSR. The notion that females stress social relationships, responsibilities, and care when dealing with moral issues whereas men emphasize individual rights and justice (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1982; Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, & McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017; Walker, de Vries, & Trevethan, Reference Walker, de Vries and Trevethan1987) appears to be applicable to Vietnam which could explain the negative attitudes of Vietnamese male vis-à-vis female students toward social and ethical responsibilities. While the socio-cultural expectation of Vietnamese males, as heads of family, is to provide for livelihoods, it is plausible that their negative perceptions of CSR outweighed their view on CSR's importance for short-term financial gains. As male students relate negatively to CSR-STC only, H5 is partially supported.

CSR-STC is positively related to student seniority (β = .321, p < .01). This finding is similar to those in prior studies such as Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, and Rodriguez-Pomeda (Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015) and Kumar (Reference Kumar1995). Our finding suggests that senior students tended to agree with the importance of CSR to short-term competitiveness. The positive effect could be due to senior students being more knowledgeable on CSR and business after taking relatively more courses in these areas. Specifically, senior students could have developed a perception on the role of CSR in a fast-moving transitional economy like Vietnam where firm survival is precarious and uncertain. Firms must not only be concerned with long-term sustainability but also ensure viability in the short-term. While beneficial for long-term business sustainability, CSR is also important for boosting short-term sustenance, especially with the push from foreign MNCs to practice CSR in Vietnam. Nguyen, Hoang, and Luu (Reference Nguyen, Hoang and Luu2019) found that many CSR practices in Vietnam were encouraged by MNCs for the benefit of creating new, immediate market opportunities. CSR could thus be perceived by senior students as important for short-term success. As senior students were found to relate positively to CSR-STC only, H6 is partially supported.

Characterization of Vietnamese CSR attitudes

Collectively, our findings represent a characterization of the CSR attitudes of Vietnamese business students. A Vietnamese business student who is idealistic or relativistic is likely to support CSR. A spiritual business student tends to view CSR as important to long-term sustainability and profitability but rejects CSR's importance to short-term success. A senior student is inclined to support CSR while a male student would consider CSR less favorably.

Compared to western business students (Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete, & Rodriguez-Pomeda, Reference Alonso-Almeida, Fernández de Navarrete and Rodriguez-Pomeda2015; Arlow, Reference Arlow1991; Haski-Leventhal, Pournader, & McKinnon, Reference Haski-Leventhal, Pournader and McKinnon2017; Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Vitell, Ramos, & Nishihara, Reference Vitell, Ramos and Nishihara2010), Vietnamese business students who were idealistic, materialistic, males, or senior tended to express similar attitudes as their western counterparts toward CSR. While a relativistic Vietnamese business student is supportive of CSR, this is in contrast to the relativistic western student (Kolodinsky et al., Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010; Singhapakdi et al., Reference Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli and Kraft1996; Vitell, Ramos, & Nishihara, Reference Vitell, Ramos and Nishihara2010) but in alignment with a relativistic Asian student (Chen, Mujtaba, & Heron Reference Chen, Mujtaba and Heron2011; Etheredge, Reference Etheredge1999). With Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk and Henkel2010) as one of the very few studies to include spirituality and not finding it significant, our finding in spirituality represented new evidence on the relevance of spirituality in affecting the CSR attitudes of business students. These attitude characteristics could be shaped by Vietnamese cultural, economic, and social contexts such as Confucian and religious values, collectivism, socialism, and traditional gender role expectations.

Theoretical contributions and managerial implications

With rapid implementations of CSR globally and recognition of CSR as a highly contextualized concept (Davidson, Reference Davidson and Örtenblad2016; Nguyen, Bensemann, & Kelly, Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018), our study makes a theoretical contribution to the understanding of CSR attitudes of business students in Vietnam, a new context in the literature. By analyzing our Vietnamese findings against extant literature, our study not only offers insights on the extent of universal applicability of existing CSR models but also contributes to the understanding of CSR in developing economies with similar cultural and social features and economic ambitions as Vietnam. Despite calls to derive better CSR outcomes from more context-sensitive research and understanding at the individual level of analysis (Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012; Nguyen, Bensemann, & Kelly, Reference Nguyen, Bensemann and Kelly2018), few research efforts have addressed the issue of examining how business students as future managers perceive CSR, especially in developing economies.

From a theoretical perspective, our findings provided reinforcing empirical evidence to validate the contextual nature of CSR. While findings on idealism, materialism, student seniority, and gender were generally consistent with previous studies suggesting these predictors' global relevance and applicability, the relativism and spirituality predictors were found to deviate from the extant literature.

Explanations on the positive effect of relativism on CSR using the cultural context of collectivism and Confucian teaching of moderation (or Dieu Do) strengthen the impetus for future theoretical work on CSR to incorporate contextual elements in their studies. The positive effect of relativism also accentuates a pattern of results, suggesting a distinct differentiation of how relativism affects business student attitudes between western and east Asian regions. This has implications for the theoretical development and understanding of CSR in these regions.

Our study represents one of the first to find spirituality significant in predicting the CSR attitudes of business students. While the importance of spirituality to CSR and managers has been highlighted (e.g., Brammer et al., Reference Brammer, Williams and Zinkin2007; Cavanagh, Reference Cavanagh1999; Vu, Reference Vu2018), our finding provided empirical support to strengthen the case for the inclusion of spirituality as a key variable in the conceptualization of CSR. The possible influence of Buddhism principles, which are generally in alignment with CSR ideologies, on the Vietnamese indicates the importance of cultural context in understanding CSR and the relationship between religion and spirituality. Our finding on the contrasting effects of spirituality on CSR's importance to long-term sustainability and short-term benefits appear to reflect Buddhist views and business practices in Thailand (Suriyankietkaew & Kantamara, Reference Suriyankietkaew and Kantamara2019), suggesting a possible similar influence of religion in spirituality and attitudes in east Asia.

Our study contributes to the identification of characteristics of CSR attitudes of Vietnamese business students. The specific characteristics are conceptualized based on the comparison of attitudes between Vietnamese business students and their counterparts elsewhere as well as explanations of the findings from Vietnamese cultural, economic, and social contexts.

Our findings have important managerial implications for business and education organizations. First, the similar findings on the effects of idealism and materialism on CSR between our study and those using western subjects suggest that the attributes of having moral value to do good to others and the desire to gain worldly materials for self-gratification could be universal among business students. An implication is that employers can expect idealistic business students from different geographical locations to carry a positive orientation and attitude toward CSR. Likewise, materialistic business students, in general, would view CSR negatively. With increasing global mobility of graduates seeking jobs, this finding has implications on the recruitment process for business students from different geographical locations, as long as employers are able to assess and determine the idealistic and materialistic inclinations of the job candidates. The findings could also assist educators in developing curriculum and career counsellors in providing better job selection advice after they have evaluated the student's posture on idealism and materialism.

Referencing our finding on spirituality, organizations wishing to cultivate a CSR culture can focus on building a more spiritual work environment to nurture higher spirituality among their employees. As spirituality deals with personal meaning in life, organizations could also develop spiritual leadership to lead by example and establish long-term visions and goals that convey meaningful, spiritual purpose and fulfillment. The focus of spirituality efforts should target long-term rather than on short-term perspectives.

Our findings reveal that male students tended to have a negative view of CSR's impact on short-term success. An implication is that recruiters can use this orientation to select new hires to better match hiring objectives and organizational expectations. Educators can use this finding as a basis to tailor modules and student interactions to different students to achieve desired learning outcomes.

Conclusion and future research directions

The study enriches the literature as one of the first to rigorously identify the predictors of CSR attitudes of Vietnamese business students. From a theoretical perspective, the study advances the understanding of CSR development in a new, non-western country context defined by distinct economic, cultural, and social features. Similar to Wang and Calvano (Reference Wang and Calvano2015) and Zhao, Lee, and Moon (Reference Zhao, Lee and Moon2019) in using multiple theories to substantiate their research, the study used stakeholder theory, theory of planned behavior, and ethical ideology framework to provide theoretical grounding and support. The findings provide a CSR profile of business students that could assist organizations to better identify suitable hires for CSR roles, assimilate new hires into effective CSR managers and achieve desired CSR outcomes. This is particularly important to Vietnamese organizations given the increased demands from international markets and foreign investors to step up CSR. Education institutions can also use our findings to improve curriculum, student engagement, and job placement. The findings and insights generated from the study also serve as a basis for future comparative studies on similar CSR themes.

Future research could take the form of replication to gain a more robust theoretical understanding of context. Research could seek to validate our findings in new country and cultural contexts. The fast evolving Vietnamese economy could also entail longitudinal research to track how cultural and social elements impact CSR practices and implementation. The identification of various dimensions of the variables (e.g., CSR construct) could be examined further because these dimensions reflect the underlying characteristics of the data collected. Differences in dimensions across studies could generate insights into the nature of contexts. Studies could also focus on specific predictors. In particular, our finding on relativism appears to reinforce a discernable difference of results between studies using western and East Asian subjects. Spirituality could be included as a predictor to further assess its impact on CSR attitudes, especially in the context of its relationship with the practice of religiosity. Interaction effects between predictors could also be examined to enrich the understanding of how predictors affect each other. Future research could examine more closely how factors including culture, social norms, and traditions affect the interpretation and practice of relativistic beliefs of business students toward CSR. More research is needed to provide a more definitive understanding of the CSR–relativism relationship. As exposure to CSR concepts and practice could shape perceptions, future research could study how the quantity and quality of CSR-related courses taken by business students affect their CSR attitudes.

Hauthikim Do is a faculty member at Becamex Business School, Eastern International University, Vietnam. She has an LLB degree in Commercial Law from the University of Law, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and an MSc in Management from the University of Nottingham Trent, UK. Her current research interests include the impact of corporate ethics and social responsibility on Vietnamese companies, role of ethical leadership in the Vietnamese business ecosystem, employment relations, and human resource management.

Chee Chuong Sum was a Professor at Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT). He previously served as Co-President at Eastern International University, Vietnam, and faculty at NUS Business School, National University of Singapore (NUS). He has a BEng (Hons) degree from the National University of Singapore and holds a PhD in Business Administration (Operations Management) from the University of Minnesota, USA. His research has appeared in leading international journals such as Journal of Operations Management, Decision Sciences, IIE (Trans), European Journal of Operational Research, and Omega. His research interests include operations and supply chain capabilities, operations strategy, global operations, leadership, and business ethics.