Tongan (lea fakatonga, ISO 639-3 code ton) is a Polynesian language spoken mainly in Tonga, where it is one of two official languages (with English). There are about 104,000 speakers of the language in Tonga, with nearly 80,000 additional speakers elsewhere (Simons & Fennig Reference Simons and Fennig2017). It is most closely related to Niuean, and more distantly related to West Polynesian languages (such as Tokelauan and Samoan) and East Polynesian languages (such as Hawaiian, Māori, and Tahitian). Previous work on the phonetics and phonology of Tongan includes a general grammar (Churchward Reference Churchward1953), a dissertation with a grammatical overview (Taumoefolau Reference Taumoefolau1998), a phonological sketch of the language (Feldman Reference Feldman1978), two dictionaries (Churchward Reference Churchward1959, Tu‘inukuafe Reference Tu‘inukuafe1992), journal and working papers on stress (Taumoefolau Reference Taumoefolau2002, Garellek & White Reference Garellek and White2015), intonation (Kuo & Vicenik Reference Kuo and Vicenik2012), as well as the ‘definitive accent’ (discussed below) and the phonological status of identical vowel sequences (Poser Reference Poser, Goldberg, MacKaye and Wescoat1985; Condax Reference Condax1989; Schütz Reference Schütz2001; Anderson & Otsuka Reference Anderson and Otsuka2003, Reference Anderson and Otsuka2006; Garellek & White Reference Garellek and White2010; Ahn Reference Ahn2016; Zuraw Reference Zuraw2018). This illustration is meant to provide an overview of the phonetic structures of the language, and includes novel acoustic data on its three-way word-initial laryngeal contrasts, which are cross-linguistically rare. The recordings accompanying this illustration come from Veiongo Hehepoto, a native speaker of Tongan currently living in Melbourne, Australia. Ms. Veiongo was born in 1950 on the island of Vava‘u (northern Tonga), but grew up and was educated in the capital city Nuku‘alofa on Tongatapu (see Figure 1). She moved to Vanuatu when she was 16 years old, and when she was 21 moved to Australia where she trained as a nurse. She continues to speak Tongan every day with family members (including children, who were born in Australia) and friends.

Figure 1 Map of Tonga and surrounding islands, created using ggmap (Kahle & Wickham Reference Kahle and Wickham2018). Our speaker was born on Vava‘u island in northern Tonga, but grew up in the capital city Nuku‘alofa, on Tongatapu island.

Consonants

Examples of the consonants are shown below in both word-initial and word-medial positions, with both broad phonemic transcriptions and their orthographic representations. Consonants do not appear word-finally. Due to a sound change *t → /s/ before /i/ (Morton Reference Morton1962), sequences of /ti/ are rare and are restricted to loanwords.

Consonants in word-initial position

Consonants in word-initial and word-medial positions

Feldman (Reference Feldman1978) describes /t n/ as apico-dental, /l/ as an apico-alveolar lateral (flap), and /s/ as lamino-alveolar. In intervocalic position, /k/ sometimes spirantizes to [x] or [ɣ]; compare [k] vs. [ɣ] in two tokens of /fakaaoaoʔi/ fakaaoao‘i ‘act like a despot’. This process appears to be optional, and is also attested in neighbouring Niuean (Brown & Tukuitonga Reference Brown and Tukuitonga2018).

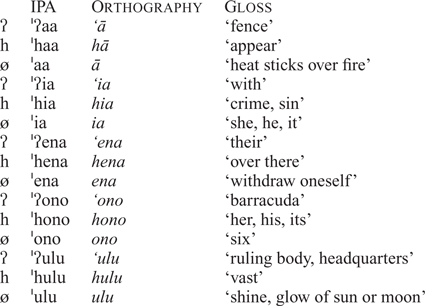

Tongan has a three-way laryngeal contrast in initial position; words may begin with /ʔ/, /h/, or a vowel. This is a rare contrast across languages; it is attested in other Malayo-Polynesian languages, and is also said to be marginal in some Mayan languages (see discussion in Garellek Reference Garellek2013: 9–10). At the beginning of utterances, Tongan vowel-initial words may begin with weak voicing and slight breathiness.

Three-way laryngeal contrasts utterance-initially

Three-way laryngeal contrasts word-medially

We analysed the voice quality of vowels adjacent to the three-way laryngeal contrast in both utterance-initial and word-medial positions. For utterance-initial tokens, we segmented the initial vowel, ignoring the preceding consonant if present. For word-medial tokens, we segmented the entire V(C)V sequence. We then used VoiceSauce (Shue et al. Reference Shue, Keating, Vicenik and Yu2011) to measure H1*–H2*, Cepstral Peak Prominence (CPP), and f0 over the segmented intervals. H1*–H2* is the difference in amplitude between the first and second harmonics, corrected for the effects of formants. Higher values index a voice quality with greater vocal fold spreading, i.e. a breathier or less creaky voice quality. CPP is a harmonics-to-noise ratio measure; lower values index a noisier voice quality, i.e. a breathy quality with more aspiration noise, or a creaky quality with less periodic voicing. Therefore, breathier vowels should have a higher H1*–H2* and lower CPP (relative to a more modal vowel), whereas creakier vowels should have both a lower H1*–H2* and CPP relative to a more modal vowel (Gordon & Ladefoged Reference Gordon and Ladefoged2001, Garellek & White Reference Garellek and White2015).

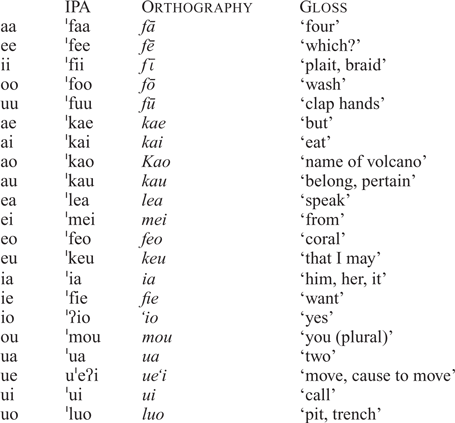

The time courses of f0, H1*–H2*, and CPP for utterance-initial vowels are plotted in the top panels of Figure 2. As expected, vowels following initial /ʔ/ have lower H1*–H2* (but comparable CPP) compared with vowels following initial /h/. The H1*–H2* difference remains for most of the vowel’s duration. CPP rises towards the middle of the vowel (regardless of initial stop), because this portion of the vowel is most periodic (see also Garellek Reference Garellek2012). CPP remains lower for vowels after /ʔ/ than those following /h/, suggesting that the effect of /ʔ/ on adjacent vowels is longer lasting than the effect of /h/. Vowels following /ʔ/ also begin with a lower f0 than vowels following /h/, likely due to the presence of creaky voice for the former. Creaky voice tends to trigger a lower and less regular f0 on adjacent vowels (Gordon & Ladefoged Reference Gordon and Ladefoged2001, Keating, Garellek & Kreiman Reference Keating, Garellek and Kreiman2015). The f0 difference between vowels following /ʔ/ vs. /h/ disappears about one-third of the way through the vowel.

Figure 2 Time courses of f0, H1*–H2*, and CPP for the three-way laryngeal contrast in utterance-initial (top) and word-medial (bottom) positions. The x-axis represents mean normalized time. For utterance-initial tokens (top), the time course represents the duration of the initial vowel only for word-medial tokens (bottom), the time course represents the duration of the V(C)V sequence.

As mentioned above, utterance-initial vowels not preceded by a consonant are generally breathy. This is shown for H1*–H2* and CPP in the top panels of Figure 2: vowels not preceded by a consonant have comparably high values of H1*–H2* and low values of CPP as vowels following /h/. In fact the low CPP remains for the first half of the vowel, indicating that the breathiness for vowels not preceded by consonants lasts longer than that of vowels following /h/. Moreover, vowels not preceded by a consonant have a much lower f0 (by about 30–40 Hz) than vowels following both /h/ and /ʔ/; whereas the lower f0 of vowels following /ʔ/ lasts for about a third of the vowel’s duration, the lower f0 of vowels not preceded by a consonant lasts for most of the vowel’s duration. Because breathy voice often co-occurs with lower or falling pitch in languages of the world (Gordon & Ladefoged Reference Gordon and Ladefoged2001), we believe that this f0 lowering is due to the breathy implementation of onsetless vowels.

The time courses of f0, H1*–H2*, and CPP for word-medial V(C)V sequences are plotted in the bottom panels of Figure 2. As expected, /VʔV/ sequences show a dip in H1*–H2*, CPP, and f0 centred around halfway through the sequence, where creaky voice is strongest. /VhV/ sequences also show a dip in CPP (due to aspiration noise) but only a small rise in H1*–H2* (perhaps because the strong voiced frication of intervocalic /h/ interacts acoustically with the voice source). In contrast, /VV/ sequences with no intervening laryngeal consonant show high and more stable H1*–H2* and CPP values, indicating that these sequences are more modal in their production than either /VʔV/ or /VhV/ sequences.

Vowels

Tongan contrasts five vowels, /i e a o u/. Figure 3 shows the mean F1 and F2 values for vowels produced by our speaker (see also data for four female speakers in Garellek & White Reference Garellek and White2015).

Figure 3 Acoustic vowel plot showing mean F1 and F2 values from the Tongan recordings of one female speaker in this illustration (see also Garellek & White Reference Garellek and White2015).

Vowels in word-initial position

Vowels in word-final position

Word-final unstressed vowels, especially the high vowels /i u/, can undergo devoicing, especially when they occur phrase-finally (Morton Reference Morton1962, Feldman Reference Feldman1978). Final unstressed /i/ can also be elided completely; in the story, there are tokens of /mataŋi toŋaa/ matangi Tongá ‘the South Wind’ that are realized as [maˈtaŋ] (see phonetic transcription below). Long homorganic vowel sequences are usually analysed as being sequences of identical vowels (Taumoefolau Reference Taumoefolau1998, Reference Taumoefolau2002; Anderson & Otsuka Reference Anderson and Otsuka2006; Garellek & White Reference Garellek and White2015; see also discussion in Zuraw Reference Zuraw2018). Sequences of non-identical vowels are likewise considered not to be diphthongs (Taumoefolau Reference Taumoefolau1998, Reference Taumoefolau2002; Anderson & Otsuka Reference Anderson and Otsuka2006) though it has been observed that some sequences – especially those ending in a higher vowel – may sometimes be realized as diphthongs (Churchward Reference Churchward1953, Feldman Reference Feldman1978, Poser Reference Poser, Goldberg, MacKaye and Wescoat1985, Schütz Reference Schütz2001); Garellek & White (Reference Garellek and White2010) find some acoustic evidence for this claim. We discuss this in more detail in the ‘Stress’ section below.

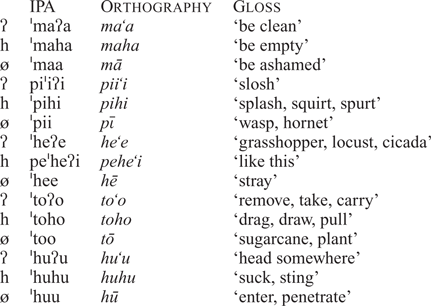

Vowel sequences

As with other Polynesian languages, words in Tongan may have sequences of many vowels. Sequences of all vowels are permitted, and sequences of up to seven vowels are attested (Morton Reference Morton1962: 21). Examples of up to six vowel sequences are shown below.

Stress

Garellek & White (Reference Garellek and White2015) found that phrase-medial vowels with primary stress have higher f0, higher F1, longer duration, higher energy, and more periodic voice quality relative to unstressed vowels. (However, final stressed vowels at the end of an intonational phrase often have a low pitch accent, as discussed below.) All stressed vowels (even high ones) show a higher F1 than unstressed vowels, suggesting that stressed vowels are lowered in the vowel space due to sonority expansion. But as the authors mention (Garellek & White Reference Garellek and White2015: 29–30), some of these correlates may belong to post-lexical (accentual) prominence, rather than to primary lexical stress. Vowels with secondary stress (and no pitch accent) are marked by higher f0 and energy, but shorter duration than unstressed vowels.

Primary stress in Tongan almost always falls on the penultimate mora of a phonological word (or ‘stress group’, see Taumoefolau Reference Taumoefolau1998), which may include a content word plus clitics, and affixes. For instance, the present tense marker ‘oku may have stress on either syllable, depending on the number of syllables in the following verb (plus enclitics): compare from the story [(ˌʔoku)(ˈʔalu)] ‘oku ‘alu ‘goes’ vs. [ʔo(ˌkune)(ˈtui)] ‘oku ne tui ‘wearing-3sg’. Secondary stress placement depends on morphology (Feldman Reference Feldman1978) and can be variable for loanwords (Zuraw, O’Flynn & Ward Reference Zuraw, O’Flynn and Ward2010).

One common process that interacts with stress in the language is the ‘definitive accent’, which marks definiteness, specificity, or uniqueness (Churchward Reference Churchward1953; Clark Reference Clark1974; Feldman Reference Feldman1978; Condax Reference Condax1989; Schütz Reference Schütz2001; Anderson & Otsuka Reference Anderson and Otsuka2003, Reference Anderson and Otsuka2006; Ahn Reference Ahn2016). The definitive accent involves the addition of a mora (whose quality is a copy of the phrase’s final vowel) to the end of the relevant phrase, which induces a leftward stress shift; compare two tokens of tangata ‘man’, kote ‘coat’, and puhi ‘blow’ from the story: [ha taˈŋata] ha tangata ‘a man’ vs. [he taŋaˈtaa] he tangatá ‘the man-def.acc’; [ha ˈkote] ha kote ‘a coat’ vs. [ˌhono koˈtee] hono koté ‘his coat-def.acc’; [ne ˈpuhi] ne puhi ‘(he) blew’ vs. [ˌʔe ne puˈhii] ‘e ne puhí ‘(the more strongly) he blew-def.acc’. (Orthographically, the definitive accent can be marked unambiguously by an acute accent, but may also be marked with a macron, just like unaccented sequences of identical vowels where the first vowel is stressed. Sometimes the definitive accent is orthographically unmarked.)

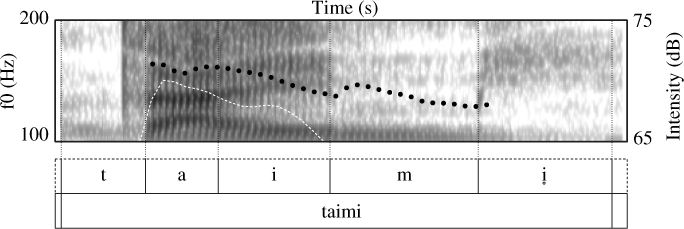

As mentioned earlier, adjacent vowels are typically treated as sequences rather than long vowels (if homorganic) or diphthongs (if heterorganic). However, in cases of falling diphthongs like /ai au ao/, there is some evidence that stress can shift leftward to the higher-sonority vowel, even if antepenultimate. One example of this in the story is for the word [ˈtaimi̥] taimi ‘time’, which is an English loanword. That word has a higher f0 and intensity on the [a], even though stress should ordinarily be expected to fall on the penult [i] (Figure 4). In fact, Feldman (Reference Feldman1978: 136) assumes that the word taimi ‘time’ always has antepenultimate stress, presumably because of the word’s stress pattern in English. We note that this example is problematic, given its status as a loanword. However, Garellek & White (Reference Garellek and White2010) show that native Tongan words with falling vowel sequences also exhibit acoustic correlates of diphthongization and stress shift. Unfortunately, no such native Tongan words were elicited explicitly or were present in the passage.

Figure 4 Spectrogram of taimi ‘time’ from the passage. The black speckled line is the f0 track, and the white dashed line is the intensity track. Note that the f0 and intensity peaks occur on the antepenultimate vowel.

Intonation

The intonation of Tongan has recently been analysed (Kuo & Vicenik Reference Kuo and Vicenik2012) within the autosegmental–metrical framework (Ladd Reference Ladd2008). The authors find evidence for two tonally marked levels of phrasing in Tongan: the intonational phrase (IP) and the accentual phrase (AP). The IP corresponds roughly to a full utterance or major phrase, and is marked at its right edge by a boundary tone (a high tone, an upstepped high tone, a low tone, or a rising tone). The AP usually contains one lexical word plus preceding function words, and ends with an AP edge tone (a high tone or a low tone). The head of the AP is the vowel bearing primary stress, which is marked by a pitch accent, usually a rise or (in the case of the final pitch accent in a declarative sentence) a low/falling target (see Figure 5). According to Kuo & Vicenik (Reference Kuo and Vicenik2012), focus is realized intonationally via increased pitch range on the focused constituent.

Figure 5 An f0 track of the phrase ‘oku ne tui ha kote māfana ‘wearing a warm coat’ from the story, with intonational annotations based on the model proposed by Kuo & Vicenik (Reference Kuo and Vicenik2012).

As in other Polynesian languages, Tongan allows for very long lexical items with over 10 vowels, such as /fefakavahaʔapuleʔaŋaʔaki/ fefakavaha‘apule‘anga‘aki ‘to vie with each other as nations’ and /ŋaauetootooivimaalohiʔaki/ ngāuetōtōivimālohi‘aki ‘to use zealously and industriously’. In such cases, a word may or may not be broken up into multiple APs, which are cued by final phrase accents and AP-final lengthening. Compare one token of fefakavaha‘apule‘anga‘aki ‘to vie with each other as nations’, with only one AP (shown in the top panel of Figure 6), and a token of ngāuetōtōivimālohi‘aki ‘to use zealously and industriously’ with three APs (bottom panel of Figure 6). The first word is marked as having one AP because no word-medial lengthening is perceived, and because there is no evidence of pitch targets other than the pitch accents associated with stressed syllables and the IP-final boundary tone. The second word has clear AP-final lengthening associated with the right edge of both word-medial APs. Vowels with secondary stress may also receive pitch accents; for example, all syllables with secondary stress in the word [feˌfakavaˌɦaaˌpuleˌʔaŋaˈʔaki] fefakavaha‘apule‘anga‘aki ‘to vie with each other as nations’ bear a pitch accent.

Figure 6 An f0 track of the fefakavaha’apule’anga’aki ‘to vie with each other as nations’ with only one AP (shown in the top panel), and a token of ngāuetōtōivimālohi’aki ‘to use zealously and industriously’, with three APs posited, based on the model proposed by Kuo & Vicenik (Reference Kuo and Vicenik2012). The presence of an AP is determined primarily by the percept of lengthening, as well as an AP-final phrase accent.

Transcription of recorded passage

Broad phonemic transcription

mataŋi toŋaa mo e laʔaa

ne alea ʔa e mataŋi toŋaa pea mo e laʔaa pe ko hai ʔoku maalohi tahaa, lolotoŋa ena aleaa ʔoku ʔalu hake ha taŋata ʔoku ne tui ha kote maafana. naʔa na felotoi ko ia ko ee te ne fai ha meʔa ke vete ai ʔe he taŋataa hono kotee ko e maalohi tahaa ia. ne puhi ʔe he mataŋi toŋaa ʔaki hono maalohi tahaa, ko e maalohi aŋe ʔe ne puhii, ko e to e maalohi aŋe ia hono takatakai ʔe he taŋataa ʔa hono kotee, faifai pea fakafisi ʔa e mataŋi toŋaa. pea ulo maafana ʔa e laʔaa, ʔikai hano taimi, kuo vete ʔe he taŋataa hono kotee. ne tukulolo leva ʔa e mataŋi toŋaa ʔo ne tala ko e laʔaa ʔa e maalohi tahaa ia na uaa

Phonetic transcription

maˈtaŋ toˈŋaː mo ĕ laˈa̰ː

ˌne̤ aˈlea ˌa maˈtaŋ toˈŋaː ǀ ˌpea ˌmo e laˈa̰ː ǁˌpe ko ˈɦai ˌog ˌmaːˈloi̤ taˈɦaː ǁˌloloˈtoŋa ĕˌna aleˈaː ǁˌo̰kŭˈa̰lu ˈɦakĕ̤ a̤ taˈŋata ǁ ʔoˌku ne ˈtui ɦa ˈkote ˌmaːˈfana ǁ naˈa na ˌfeloˈtoi ǁ ko ˈia ko ˈeː te ǀne ˈfai ɦa ˈmea̰ ǁ ke ˈvete ˈai ḛ e ˌtaŋaˈtaː ǀ ˈɦono koˈteː ǁ ko ĕˌmaːˈloi̤ tăˈɦaː ia ǁ ne ˈpuɦi e e maˈtaŋi toˈŋaː ǁˈʔaki̥ ˈhono ˌmaːˌloi̤ taˈɦaː ǁˌko ĕˌmaːˈloɦi ˈaŋe ǀ ḛ ne puˈɦiː ǁ kŏ e to e ˌmaːˈloi̤ˈaŋe ˈia ǀ ˈho̰no ˌtaɣataˈkai eːˌtaŋaˈtaː ǁ a̰ ˈɦono koˈteː ǁˌfaiˈfai ˌpeăˌfaɣaˈfisĭ a ĕ maˈtaŋ toˈŋaː ǁˈpḛa ˈulo ˌmaːˈfana ˌa ĕ laˈa̰ː ǁʔiˈkai̤ˈano ˈtaimi̥ ǁˌkuŏˈvete ɦe ˌtaŋaˈtaːˌɦono koˈteː ǁ ne ˌtjuɣuˈlolo ˈleva ǀ ˌa̰ ĕ maˈtaŋ toˈŋaː ǁˌʔo ne ˈtala ǁˌko ĕ laˈʔaː ǀ ˌʔa ĕˌmaːˈloi̤ˈtaɦaː ǀ ˈḭa na uˈaː ǁ

Orthographic version

Matangi Tongá mo e La‘á

Ne alea ‘a e Matangi Tongá pea mo e La‘á pe ko hai ‘oku mālohi tahá, lolotonga ena aleá‘oku ‘alu hake ha tangata ‘oku ne tui ha kote māfana. Na‘a na felotoi ko ia ko ē te ne fai ha me‘a ke vete ai ‘e he tangatá hono koté ko e mālohi tahá ia. Ne puhi ‘e he Matangi Tongá‘aki hono mālohi tahá, ko e mālohi ange ‘e ne puhí, ko e to e mālohi ange ia hono takatakai ‘e he tangatá ‘a hono koté, faifai pea fakafisi ‘a e Matangi Tongá. Pea ulo māfana ‘a e La‘á, ‘ikai hano taimi, kuo vete ‘e he tangatá hono koté. Ne tukulolo leva ‘a e Matangi Tongá‘o ne tala ko e La‘á ‘a e mālohi tahá ia na uá.

English translation

The South Wind and the Sun

The South Wind and the Sun were discussing who was strongest, when a man walked past wearing a warm coat. They agreed that whoever would get the man to take off his coat would be considered the strongest. The South Wind blew with all his strength, but the stronger he blew, the more tightly the man wrapped his coat around himself. Eventually the South Wind gave up. Then the Sun shone strongly on the man, and this time the man took off his coat. The South Wind immediately was forced to admit that the Sun was the stronger of the two.

Acknowledgements

We are especially grateful to our speaker Veiongo Hehepoto for reviewing and recording the words and ‘The South Wind and the Sun’ passage, which was translated into Tongan with the help of Helen Lee. We are also thankful to Casey Ford for her work in labelling the database, to Margaret Purdam for help with the recording, to André Radtke for reviewing the sound files, to Editor Amalia Arvaniti and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions, and to Ewa Jaworska for editorial assistance. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (via a Future Fellowship awarded to Marija Tabain) and the Linguistics Disciplinary Research Program at La Trobe University.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100318000397.