It is no secret that liberal democracy is in trouble around the world. The number of democracies in the world peaked around 2006, and has declined in each year since then. Some young democracies have been lost, and even long-established democracies have seen erosion in the quality of democratic institutions. There is a small cottage industry of books and articles lamenting democracy's decline, and the most recent version of the well-known Freedom in the World report is subtitled Democracy in Crisis.Footnote 1 More broadly, the global liberal order is under assault from populists, economic nationalists, and autocrats. Human rights, too, has been eulogized in a series of recent books on the “twilight” or “endtimes” of human rights.Footnote 2

To be sure, the situation could change, and there are several recent examples of jurisdictions that reversed their slippage toward autocracy.Footnote 3 From Armenia to Malaysia, it seems a bit too soon to count on the inevitable death of democracy. But there are also long term trends that cut in the other direction. Western democracies dominated the global economy for much of the 1990s, producing well over half of world gross domestic product. However, at some point in the next five years, some believe that the total share of global output produced by dictatorships will surpass that of the Western democracies, which will fall to less than a third.Footnote 4 China is now a major source of outbound capital, and the world's largest official creditor.Footnote 5 With less than half the world's population now living in nations that are fully or even “flawed” democracies, there is a strong possibility that the twenty-first century will be known more as an authoritarian century than a democratic one. These trends suggest that it is worth trying to understand what impact rising authoritarianism will have on international law.

There are three major features of today's authoritarian regimes that are important to understand, in contrast with previous eras. First, today's dictatorships are for the most part integrated into the global capitalist economy, and so rely heavily on international trade, labor, and investment flows. An autocratic country is not an autarkic one. This means that there will be continuing demand for some regional and global public goods from dictatorships and democracies alike, especially in the economic sphere. Relatedly, uniform market regulations benefit all, and regulatory power is as important for markets as military power is for security.Footnote 6 Battles over global regulation, which have heretofore been fought mainly between the United States and the European Union, will now involve China and perhaps other nondemocratic countries to a greater degree.

A second feature is the relative decline of ideology. To be sure, there are some authoritarians that rely heavily on ideological rhetoric, such as Venezuela under Nicolas Maduro or theocratic Iran. But the powerful appeal of global communism or political Islam are largely things of the past, and many authoritarian regimes are driven more by a desire for political survival than a consistent ideological message. In the new “marketplace of political change” authoritarians are increasingly assertive, but less ideologically motivated, relative to earlier eras.Footnote 7

Another major feature of our time is the abuse of democratic forms for anti-democratic purposes. Many of today's authoritarians have constitutions with long lists of rights, which in form are scarcely distinguishable from those found in democratic orders.Footnote 8 They have courts that are structurally independent, with genuine power over certain realms of activity. They hold regular elections, and have nominally independent accountability bodies. But these institutions function in completely different ways than they do in democracies. Instead of facilitating the turnover of leaders, elections in authoritarian regimes are designed to elicit information and consent from the public, so as to extend the political lives of leaders.Footnote 9 Instead of providing a check on the ruler, courts are designed to support market transactions and discipline low-level administrative agents, but not hold the core power itself accountable.Footnote 10 In some cases, courts become an instrument of rulers, and we have recently seen several instances in which national high courts have relied on international law to help leaders extend their terms of office beyond what the constitutions allowed.Footnote 11 Constitutions in such countries are not designed to limit power but rather to exhort the people toward ideological goals, or to provide for formal institutions that do not operate as the real arena of power.Footnote 12 As scholars have analyzed how nominally democratic institutions benefit dictators, they have deepened our understanding of those institutions, in terms of their strengths and vulnerabilities.Footnote 13

In this spirit, this Article introduces the concept of authoritarian international law, documents some nascent features, and speculates on its trajectory. Today's authoritarian regimes are increasingly facile in their engagement with international legal norms and institutions, deploying legal arguments with greater acuity, even as they introduce new forms of repression that are legally and technologically sophisticated.Footnote 14

Of course, in the long view, international law has always been amenable and even facilitative of authoritarian governance. The Congress of Vienna codified a conservative restoration to head off republican mobilization in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Colonialism and imperialism were blessed by supportive international legal doctrines.Footnote 15 “Proletarian internationalism” emphasized a distinct set of international legal principles.Footnote 16 Both the United States and Soviet Union used international law to justify their respective support of authoritarian regimes during the Cold War. But both intellectually and practically, the post-World War II era of international law was dominated by Western, mainly democratic nations.Footnote 17 This led to a distinct set of norms and institutions, which balanced traditional concerns about sovereignty with liberal notions of human rights and political participation.

The end of the Cold War marked a new era in which this balance seemed to shift in the direction of liberalism. Generalizing from the experience of Europe, scholars proclaimed a new era of “liberal international law” as regional and multilateral organizations expanded rapidly, and supranational adjudication increased in substantive scope and geographic reach.Footnote 18 The core idea—that international law was qualitatively different and more effective among liberal states—was well-suited to the general mood that liberalism would inevitably expand, and that international law should support this development.

This era is now decidedly over, and we may be returning to an era in which international law is facilitative of authoritarian governance. Many of those authoritarian regimes that survived the liberal wave of the 1990s did so in part because they were embedded in a global capitalist economy, itself underpinned by international legal institutions, that provided new resources for regime survival. What is distinct about our era relative to earlier ones is the way in which authoritarians are using international law, building on and repurposing some of the norms of the liberal era, but to very different ends. This Article speculates that these developments may end up shaping international law itself, at least for a large number of states.

As a threshold matter, I adopt a working definition of democracy and authoritarianism. Democracy, of course, is an “essentially contested concept”Footnote 19 for which there are nearly as many definitions as there are analysts. In a recent book, Aziz Z. Huq and I provide a relatively thin definition with three components: elections; a small set of core rights related to political contestation such as rights to free speech, association, and voting; and the rule of law, especially as applied to electoral contestation.Footnote 20 This seems to be a workable definition for thinking about pro- and anti-democratic behavior that crosses borders. Activity that seeks to enhance freedoms of speech and association, and that promotes electoral integrity, is pro-democratic, while activity directed at suppressing those things is pro-authoritarian.Footnote 21

Authoritarian regimes are incredibly diverse as a group. The category includes royal dictatorships, military juntas, and people's republics. Increasingly, we see states like Venezuela, Hungary, or Turkey, which hold elections, but an elected leader undermines the rule of law and the core rights of speech and association. Many of today's populist regimes hover near the boundary. But for purposes of this Article, they can be considered authoritarian, particularly if they utilize international law in ways that seek to undermine democratic governance as defined above. In this aspect, at least, they are not visibly different from traditional authoritarians.

The Article proceeds as follows. After introducing the concept of authoritarian international law in Part I, Part II lays out a theory about the differential use of international law by authoritarians and democrats. Part III then provides evidence to show that, consistent with the claims of many critics, international law during the post-World War II era has been by and large a product of democracies. This part uses large-n empirical methods, drawing a binary between authoritarian and democratic regimes. Such binaries are obviously simplifications, but useful for analytic purposes. Part IV turns to the main part of the Article, tracing the evolution of how authoritarian countries have sought to cooperate across borders by examining several important historical examples: the Warsaw Pact, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Eurasian Economic Community, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. I focus on regional organizations, which have served as sites for gradual learning and experimentation. Part V then provides examples of how authoritarian regimes might change the normative content of international law itself, diluting democratic norms and developing some of their own. This last feature, what I label “authoritarian international law,” is designed to extend authoritarian rule across time and space. Parts VI and VII speculate on future developments and conclude.

The changes this Article describes are not epochal, but subtle, and involve layering on existing norms and institutions. To preview the major findings, rising authoritarianism will produce shifts within existing international law structures, including the continued decline of human rights enforcement, although perhaps with more innovation in and commitment to international economic law.Footnote 22 Authoritarians have always had more use for international economic law than for rules that hamper flexibility in the political or security spheres. We may also see less use of formal third-party adjudication, and more emphasis on state-to-state negotiation and diplomacy as preferred mechanisms for resolving disputes. Finally, a greater role for authoritarians will likely accelerate long-term trends toward executive power within national constitutional orders, perhaps providing feedback effects that encourage yet more authoritarian governments. The result may be a more stable set of authoritarian regimes, interacting across borders to repress each other's opponents, with less room for international human rights or democracy promotion. This will eventually lead to the development of new norms and practices.

A word is in order about the use of evidence drawn from regional institutions. With global treaty-making at something of a standstill, we have seen a rise in regional cooperation in trade, investment, and human rights.Footnote 23 These institutions interact and cross-fertilize, with norms spreading across regions. As will be documented below, authoritarians have been increasingly creative in using regional organizations to develop new norms and to cooperate for defensive purposes. Regional law is thus a good place to look for new developments that might ultimately influence broader international norms. But it also means that the developments described here could end up being limited to particular regions or subsets of countries. Indeed, many of the claims about liberal international law were drawn from the experience of Europe.Footnote 24 Authoritarian international law, like liberal international law before it, might end up being only one element at work in the broader international legal system.Footnote 25 Nevertheless, the central claim of this Article is that this illiberal sphere is growing, potentially transformative, and normatively troubling.

I. Conceptualizing Authoritarian International Law

It is useful to begin by restating the classical view of the international legal system as facilitating ideological pluralism. While the United Nations Charter speaks of protecting fundamental human rights, it also provides for self-determination and limits the United Nations from intervening in matters “essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state.”Footnote 26 These two competing imperatives create internal tensions in the Charter, but the basic idea is that, so long as certain minimal and loosely defined standards are met, international law demands agnosticism about regime type. The central purpose of international law is not to facilitate the spread of any particular form of government but instead to facilitate the interactions of governments of very different types. From this point of view, “International law has no life of its own, has no special normative authority; it is just the working out of relations among states, as they deal with relatively discrete problems of international cooperation.”Footnote 27 International law, in essence, is neither democratic nor authoritarian, moral nor immoral, good nor bad.

This classical view has been challenged by many critics; for present purposes, the most important are scholars who have sought to deploy international law in the service of democracy. To briefly recap that literature, in 1992, just after the end of the Cold War, Thomas Franck identified what he called an “emerging” right to democratic governance.Footnote 28 In an era of high optimism about the prospects of democracy, Franck bundled a provocative doctrinal claim with a positive prediction about the future trajectory of international law, generating a serious and important debate.Footnote 29 Franck grounded his right to democratic governance on three separate pillars: the right to self-determination, which dated from the Wilsonian era; rights to freedom of expression and association, embodied in the postwar human rights architecture; and rights to political participation through elections, which he saw being implemented at the time of his writing. The expanding number of democracies provided evidence, in his view, of state practice constructing a legal norm. “Both textually and in practice,” his article concluded, “the international system is moving toward a clearly designated democratic entitlement, with national governance validated by international standards and systematic monitoring of compliance. The task is to perfect what has been so wondrously begun.”Footnote 30

Franck has been attacked on various grounds, prominently in a 2000 edited volume, Democratic Governance and International Law. Footnote 31 One powerful line of thought, associated with Professor Brad Roth, has consistently defended the international arena as one of ideological pluralism, in which a right to democracy could be destabilizing, and in which societies ought to be free to subordinate the democratic entitlement to other collective goals.Footnote 32 By turning democracy itself into a right, Franck conflated the two and puts a good deal of pressure on cosmopolitan institutions, leaving less space for democratic choice. As put succinctly by John Dryzek, if democracy were to be accepted as a universal legal right, there would be disruptive implications for international order, “for non-democratic states would become illegitimate members of the international community.”Footnote 33 Pro-democratic military intervention would then become routine, undermining the pluralist vision of international law. Indeed, this is precisely the critique that has been leveled against American foreign policy in the aftermath of the Cold War: liberal hegemony led to overreach and conflict with other great powers.Footnote 34

Another argument that liberalism has become instantiated in international law is the claim, put forward by cosmopolitans, that the foundation of international law itself relies on individual freedom and dignity. Whether a “cosmopolitan legal order” or the exercise of “legitimate public authority,” scholars working in this Kantian vein argue that the very purpose of cooperation is to advance human dignity.Footnote 35 Many of these scholars emphasize regional (especially European) arrangements as sites of liberal transnationalism. Regionalism, though, can also be used for illiberal cooperation, and this Article will provide several examples.

Let me now clarify terms. What do I mean by authoritarian international law? As Ian Hurd puts it in his superb recent book, international law allows states to “do things” that they could not accomplish without it, namely the production of public goods across borders.Footnote 36 The things that are done with international law need not be necessarily pro- or anti-democratic. One might define authoritarian international law as simply international legal interactions among authoritarian states. But as I will briefly document below, as a general matter authoritarian states do not seem to participate in the international legal order to the same degree as democracies. Democracies, it turns out, are much more likely than autocracies to conclude treaties, to litigate cases before international tribunals, and to engage in international lawmaking bodies.Footnote 37 Even if authoritarians and democrats were “doing the same things” with international law, democracies would have more impact by virtue of their more intensive interactions with the system. Much of what we have come to think of as general international law, it turns out, is the product of democratically elected governments.Footnote 38

This does not, however, make most international law inherently democratic. Instead, I define pro-democratic international law as the category emphasized by Franck: the things that democracies do with international law are designed to protect and extend the sphere of democratic governance. Examples include human rights agreements that enshrine democratic participation and core civil rights, democracy charters of regional organizations, and election monitoring.Footnote 39 But much international legal behavior by democratic governments does not have this specific character. Indeed, we know that democracies are perfectly happy to collaborate with authoritarian regimes, should economic or political motives so dictate.Footnote 40 Conversely, the mere fact that authoritarian regimes engage in certain kinds of international behavior does not itself make that behavior authoritarian in any qualitative sense. I argue that much of what authoritarians are doing is returning us to a world of Westphalian international law, primarily as a defensive measure.

But that does not mean that authoritarians will be content with Westphalian neutrality. In an interdependent world of cyberattacks, election interference, and transborder investment by state-owned entities, noninterference is more myth than reality. We should anticipate the possibility of a specifically authoritarian international law, defined as legal rhetoric, practices, and rules specifically designed to extend the survival and reach of authoritarian rule across space and/or time. Such a pro-authoritarian approach would give us three categories of international law: pro-democratic, general or regime-neutral, and authoritarian.

II. Theory: Why Would Authoritarians Be Different?

The starting point of this Article's theory is the logic of regime survival, a well-known theory in political science.Footnote 41 The assumption is that all leaders, regardless of the political system they operate in, seek to survive in office. To do so, they must provide some goods for enough of their citizens to retain power; the key differences between democracy and dictatorship lie in the size of the relevant group of beneficiaries, and the availability of information within the country. Democrats must satisfy a majority of voters, and can be monitored by their constituents with relative ease.Footnote 42 The set of people who “matter” is larger, even as large as a majority of the electorate. In a dictatorship, in contrast, the set of people who matter is smaller. It still may be a very large group—the Chinese Communist Party, for example, has nearly ninety million members at this writing. But it never approaches a majority of the society. Furthermore, to maintain power, authoritarians must manipulate information about decision making and performance.

Why should any government interested in its own survival cooperate internationally? The standard answer is that some public goods, by their very nature, cannot be produced within the borders of a single country. Two countries that share a river, for example, will not be able to manage it unless they cooperate; a set of countries interested in regional security or defense against a mutual enemy can do so by creating regional organizations that can coordinate action. Market access, too, can be helpful for some kinds of governments, particularly if they are developmental regimes with a capitalist orientation. Cooperation brings benefits, while imposing some costs in loss of control.

In thinking about whether or not to cooperate on international public goods, democracies and dictatorships may be differently situated, both with regard to propensity and type. While larger markets and access to capital may be attractive to all kinds of governments (especially for smaller states), there are some authoritarian regimes which do not desire these things for ideological reasons,Footnote 43 and others that might fear the risk of alternative power centers through open markets. Authoritarians tend to prefer segmentable public goods (“club goods”) that can be delivered to their supporters and withheld from opponents.Footnote 44 Conversely, democrats may be more likely to support human rights protection and democracy promotion as global public goods, worthy of multilateral and cross-national cooperation. Such a view might make sense for material reasons—democracies tend to trade with each other and do not go to war against each other—or for ideological ones.

Besides different issues for cooperation, time horizons and transparency also differ across regime types. In a properly functioning democratic system, time horizons are long. Democracy's survival depends on the prediction that the regime of elections will continue, even if the governing party loses power.Footnote 45 If a party thinks elections are unlikely to continue, it will not turn over office after a loss. Thus in a democracy, regime survival and government survival are by definition different: government termination depends on the prospect of regime endurance. Political parties are important here, for they extend the time horizons of politicians beyond their immediate lifetime, and can survive even when out of power. Democracy endures while its governments are finite. This generates a desire for institutions—including international law—that can commit the state beyond the life of the current government. Enduring commitment facilitates democracy because it reduces the stakes of electoral loss.Footnote 46

In contrast, in many dictatorships, regime survival and government survival are the same. Authoritarians fear revolution from below, but also displacement from other members of the elite, the most common way that authoritarians exit office.Footnote 47 The result is that authoritarians see the survival of their government as coextensive with regime survival. Of course there are ways of extending government survival across generations: If the regime is a monarchy, the leader's descendants will extend her government into the future, and this prospect in turn may induce better governance in the present. Even nonmonarchies can have clear succession rules, as did the Chinese Communist Party from roughly 1979 until 2018. But regime survival and government survival are essentially the same, at least in the eyes of the leaders. Authoritarian leaders’ “discount rate,” in turn, will reflect this identity: they will desire only those forms of international cooperation that will help the government survive.

Whereas in democracy, institutions incentivize the willing transfer of power after an electoral loss, authoritarians face graver risks from government failure. These include not just loss of power, but imprisonment, loss of assets, exile, or even death. Greater risk means that, while authoritarians desire the public or club goods that can be obtained through international cooperation, they also are mindful of unanticipated costs that might arise. They are risk-averse with regard to the future, with high discount rates for benefits, and a low discount rate for costs.

Another distinction has to do with the character of desirable cooperation. The threat of internal replacement by rivals means that, while authoritarians care a good deal about external security, internal security is a much graver concern. International cooperation that facilitates internal repression is desirable; that which risks empowering domestic political opponents is anathema.

Finally, the two types of regimes differ in their demand for transparency. Information is not freely available to ordinary citizens in an autocracy. Democracies have their secrets too, and democratic governments often seek to fool the public. But they have nothing like the closed decision-making process that characterizes authoritarian regimes.Footnote 48 An important feature of international law is its public visibility. International law involves public commitments, memorialized in treaties, statements, and public-facing behavior. The implication is that authoritarians may be concerned about overly constraining themselves in elaborate and transparent international institutions, which might create domestic backlash if anticipated benefits do not emerge. Such public evidence of a failed policy can hurt a democratic leader, but can end the authoritarian regime in its entirety.Footnote 49 The theory thus expects less hands-tying by authoritarian governments, with less public making of commitments.

Transparency also has implications for third-party dispute resolution, a central feature of the international legal order since the establishment of the Permanent Court of International Justice in 1922. Third-party dispute resolution involves the public contestation of legal issues, and may carry risk of unanticipated costs for authoritarians which exceed those for democrats. Third-party dispute resolution can generate legal or policy losses that might cause embarrassment to a democratic regime; for a dictator, however, it could lead to mobilization with the potential to topple a government. In general, we should not expect authoritarians to submit to the authority of dispute resolution bodies, at least without a specific assessment of the associated risks attendant in a particular dispute. Broad ex ante delegations to courts are less desirable than case-specific submissions in which the parties can assess the particular costs and benefits after the conflict has arisen.

The analysis so far has not taken power into account. Clearly power is a major determinant of states’ behavior in international law. The United States at the end of the Cold War, and particularly after the Clinton administration, deployed what Detlev Vagts called “hegemonic international law,” by which it sought to pick and choose which obligations it followed.Footnote 50 Vagts noted that “(t)reaties, since they represent constraints at some level on unilateral action by the parties, irritate hegemonists.”Footnote 51 Such exceptionalism is not restricted to the United States: powerful states do not like constraint, and this is true of democratic as well as authoritarian states.Footnote 52 If this is so, as relative power shifts toward authoritarian countries, we should expect treaties that are less constraining. But we ought to also recognize that some democracies, particularly the United States, are highly unrepresentative of the general category, simply by virtue of their power. The primary concern of this Article is to examine regime type, holding power constant.

To summarize: authoritarians will be interested in particular kinds of international public goods that benefit them and their supporters. We should expect, ceteris paribus, less willingness to include broad third-party dispute resolution clauses in treaties, and shallower legal commitments with more flexibility. We should also expect authoritarians to be less interested in public visibility, both in the sense of making fewer public binding commitments, and being less willing to tolerate institutions that increase domestic transparency. Authoritarian use of general international law, then, is different in theory from that of democracies, and more consistent with traditional notions of sovereignty that emphasize noninterference in internal affairs. As the number of authoritarian regimes increases, we should expect international law to increasingly take on the character of that demanded by authoritarians.

There is a further possibility, however, which is that authoritarian use of international law will support normative development that specifically enhances authoritarianism.Footnote 53 This is what I mean by authoritarian international law. Such norms might facilitate cooperation across borders to repress regime opponents, enhancing the security of authoritarian rule. They might discourage freedoms of expression and association. They might also facilitate the dilution of democratic institutions and norms through practices and rhetoric that undermine them, turning general international law more authoritarian.

This is a project that might bring together diverse authoritarian regimes, which otherwise have few ideological commonalities. There is scant evidence that authoritarians are generally cooperative with each other, and war among authoritarian regimes is frequent, in contrast with war among democracies.Footnote 54 Yet, as documented below, we have recently seen coordination on international law by regimes as diverse as Iran, Russia, and China. Such regimes have a common interest in reasserting norms of noninterference but also in developing new concepts to facilitate cross-border repression.

A large literature asks about the role of international organizations in facilitating democracy.Footnote 55 Setting aside the question of whether international cooperation is inherently undemocratic in that it removes questions from the national political conversation,Footnote 56 international organizations have been very actively engaged in the direct promotion and defense of democracy, through international norms, monitoring, and enforcement.Footnote 57 In theory, authoritarian regimes are capable of the same kind of activity, in which democratic institutions are undermined and authoritarian regimes stabilized through international cooperation.Footnote 58 A recent literature on “autocracy promotion” documents how this is done using a variety of means.Footnote 59 The consensus seems to be that today's autocracies, unlike democracies, are not inherently driven to extend autocratic form, but act defensively to resist democracy promotion and to shore up particular allies.Footnote 60 But in an increasingly interdependent world, such defensive action requires more active cooperation, which law can facilitate.

Table 1 summarizes the features of authoritarian international law, comparing and contrasting it with pro-democratic international law (into which are incorporated many of the features of liberal international law), and general international law. These are ideal types, not pure and exclusive categories, but the table is nevertheless a useful heuristic to guide the reader. The central prediction of the Article is that as the number of authoritarian regimes in the international system increases, we should observe a rightward drift in Table 1, toward active use of international cooperation to strengthen authoritarian rule, and ultimately to trying to shape the very content of international law. These shifts may not be sharp, but could result from a set of small qualitative changes that add up to a qualitative transformation, with more discourse, practices, and rules that have the characteristics described.

Table 1. Summary of Features of International Law Categories

III. Behavior of Democratic and Authoritarian Governments in the Postwar Period

In this Part, I present some basic descriptive data on core international legal behavior during the postwar period, including the formation of international law, participation in multilateral treaty regimes, the conclusion of bilateral treaties, and the willingness to bring disputes before international courts and tribunals. The evidence helps us to understand whether and how democracies and authoritarians act differently, in keeping with the theory laid out in Part II, as a way of framing the developments described in Part IV. While the large literature on the democratic peace has shown that democracies are unlikely to fight each other, the focus here is on international legal activity, which has been less systematically studied.Footnote 61

While the Article relies on a relatively thin definition of democracy as its core variable of inquiry, there is no standard empirical measure that precisely captures this definition. Indeed, the measurement of democracy is itself the object of an entire field of inquiry in political science, with a great deal of disagreement about the relationship of concepts and measures.Footnote 62 In the data that follow, unless otherwise stated, I use a standard measure for democracy: the Polity IV database, which rates countries from 10 (full democracy) to -10 (full autocracy) on a 21-point scale. This measure has the advantage of extended time coverage, going back to 1800, and is updated each year. A conventional way of transforming these data into a binary measure of democracy is to code any country-year in with a score of 6 or above in the Polity2 measure as the cutoff for democracy.Footnote 63 Using this measure, roughly 40 percent of all country-years have been democratic since 1946. If the use of international law was evenly spread across regimes, we should see democracies engaged in about 40 percent of the activity, rising above 50 percent only after 1990 with the so-called “Third Wave” of Democracy.Footnote 64

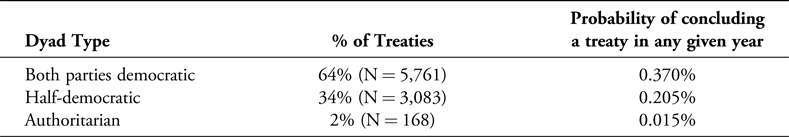

This is not what we observe. Instead, we see that democracies are overwhelmingly more likely to engage in publicly reported treaty-making. Consider first a dataset drawn from the United Nations Treaty Series (UNTS), a monthly listing that reports all treaties deposited with the United Nations. The data were initially gathered in the World Treaty Index, and supplemented with additional hand-coded data from the UNTS beginning in the year 2000, to create a dataset of more than 9,000 bilateral treaties (and several thousand multilateral treaties). I then examined the joint qualities of pairs of countries concluding bilateral treaties. As Table 2 indicates, the vast majority of these treaties were concluded by democratic dyads, even though such dyads were not a majority of possible pairs until after 1990.Footnote 65 Any given authoritarian regime is more than ten times as likely to conclude a treaty with a democracy than with a fellow authoritarian.Footnote 66

Table 2. Bilateral Treaties, 1949–2017

Source: Ward & Gleditsch; Center for Systemic Peace, supplemented by author. N = 9,012.

To be sure, these data are subject to selection effects. It is possible, even probable, that countries vary in their practice of depositing treaties with the United Nations and making them public. While international lawyers have sometimes encouraged the practice of deposit and publication, and even sought to condition legal force on the practice, the acceptance of treaties as binding ultimately depends on the decentralized behavior of individual states, which vary in both capacity and inclination.Footnote 67 While liberal democracies are also known to keep agreements secret, both theory and casual observation suggest that nondemocracies are less likely to submit treaties to public depositaries. The People's Republic of China, for example, submitted no treaties to the UNTS until 1985, fourteen years after it joined the United Nations.Footnote 68

Another way to examine differential approaches to treaty-making behavior is to ask which kinds of countries have signed the most treaties. Figure 1 below divides countries into quintiles using the Varieties of Democracy “Liberal Democracy” index, and asks which types of countries are parties to the most treaties. The highest-level democracies join more treaties by an order of magnitude. In statistical analysis available in an online appendix, I confirm this in a multivariate model, controlling for wealth, population, and the number of contiguous countries (since more neighbors implies more possibility of joint public goods production).Footnote 69

Figure 1. Treaties by Democracy Quintile

A host of other evidence shows that democracies and authoritarians behave differently on the international plane. Table 3 shows the set of contentious cases filed at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) since its establishment in 1947. While the number of such cases has risen and fallen across decades, democracies are generally overrepresented in filing cases.Footnote 70

Table 3. Contentious Cases at the International Court of Justice

Source: Author's coding from website of International Court of Justice.

Other adjudicative settings have an even more pronounced dominance by democratic countries. For example, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) was set up in 1994 under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The Tribunal operates in roughly the same way as the ICJ, in that there is both an advisory and a contentious jurisdiction, and the latter generally requires consent (with some exceptions). As of 2018, there have been twenty-five contentious cases. Only three of these—the 2002 case of The Volga brought by Russia against Australia, the 2003 case concerning Land Reclamation by Singapore in and Around the Straits of Johor brought by Malaysia against Singapore, and the 2009 case on Maritime Delimitation in the Bay of Bengal, brought by Bangladesh and accepted by Myanmar—involved claimants that were not democracies.Footnote 71 In six other cases, each involving a seizure of a fishing ship, the respondent state was a nondemocracy.Footnote 72 These cases involved demands for prompt release, brought under UNCLOS Article 292(1), pursuant to which the Tribunal has residual jurisdiction, and thus respondents had little choice but to participate.Footnote 73 Therefore, around 90 percent of cases were brought by democracies.

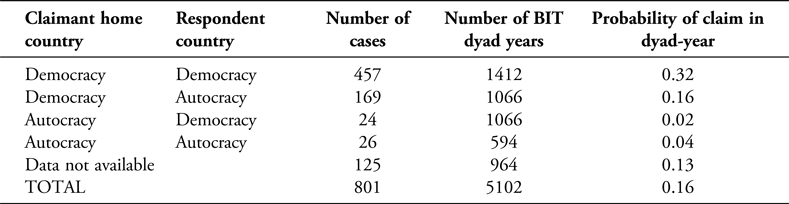

Consider also the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) system, which has come under increasing scrutiny in recent decades, as the number and variety of claims pursued under it has expanded. Table 4 shows the reported ISDS cases filed through 2015. We see that the majority of cases are between democratic dyads, even though those dyads are only around a quarter of the entire set of bilateral investment treaties (BITs). Claimants from democratic countries are far more likely to file a case—a particularly interesting finding because some claimants can choose their nationality strategically.Footnote 74 While the possibility that firms in authoritarian countries might use a subsidiary located in a democracy to bring the claim could suggest some bias in the data, any bias can also be considered evidence of the underlying point that there is some advantage to democratic home state status for investors.

Table 4. Reported ISDS Cases Through 2015

Source: Data from Weijia Rao, Domestic Politics and Settlement in Investment Treaty Arbitration (manuscript). Denominator for dyad-year is every BIT dyad since 1959, even though first ISDS claim was not filed until the 1970s.

Finally, consider the role of democracies in international organizations, which have expanded significantly in the postwar period. Figure 2 below presents selected data from the Correlates of War project on Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs).Footnote 75 One way of getting at the relative propensities of democracies to join IGOs is to ask about whether the average member of an organization is a democracy. The solid line in Figure 2 shows that the number of IGOs whose average member is democratic (as measured by Polity score) has risen over time. The number of IGOs whose average member is a “hybrid” or soft authoritarian regime, represented by the dotted line, has also been increasing over time. Such IGOs now are roughly as common as those whose average member is a democracy.

Figure 2. Number of International Organizations Over Time by Average Polity Score

I also measure, for each international organization in the data, the average percentage of democracies among the member states, in the year of IGO formation. Interestingly, the most common percentage of democracies in an IGO is either one hundred or zero. Most international organizations in other words, are composed of countries that have a similar regime type.

Part II put forward the conjecture that the structure of authoritarian-dominated international organizations would be less likely to promote transparency and third-party dispute resolution. To evaluate this claim, I examine a subset of international organizations designated as general-purpose by Cottiero and Haggard.Footnote 76 I use their independently selected set of cases and then develop original data on the internal features of on ninety-four different international organizations, using their founding charters and subsequent documents. I review whether these documents refer to terms such as security, democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, and examine several features of their legal-institutional form: whether they establish a court or legal committee of some kind, whether they grant immunity to their staff (as a possible measure of institutionalization), and the number of words in the founding charter, as an indicator of specificity and complexity of the organization. Table 5 presents the statistics on the percentage of international organizations with each feature, categorized by whether they are democratic or not (the first two columns) and then by depth of authoritarianism among members, all as defined by the average Polity score of their members in the year of founding. (The left-most column thus loosely corresponds to the right side of Figure 3, while the right-most column loosely corresponds to the left side of Figure 3.)

Figure 3. The Bimodal Distribution of International Organizations

Table 5. Internal Features of International Organizations

N = 94. Key: * indicates t-test for difference in means between that category and all others is significant at the .10 level; ** t-test significant at 5% level; *** t-test significant at .01 level.

These features of the charters establishing international organizations suggest potential differences in the ways that authoritarians and democrats cooperate. For many features of IGO charter language, we observe no general difference between the two regime types in the first two columns. Authoritarian international organization charters mention human rights and democracy at the same rate as democratic ones, and are actually more likely to contain provisions on dispute resolution and immunity for staff. But international organizations composed mostly of democracies have more detailed founding charters, implying more “precision” of obligation.Footnote 77 Furthermore, the right-most column suggests that international organizations composed primarily of deeply authoritarian regimes—the ones that may be most incentivized to use what I call authoritarian international law—are indeed less likely to use the fig-leaf of talk about human rights and democracy, and are less likely to establish third-party dispute resolution mechanisms in the form of a court.

In related work, I have provided many more examples of how authoritarian and democratic countries differ in their use of international law, with the latter being more likely to deploy international law and use its institutions.Footnote 78 These findings are consistent with the work of many other scholars. In trade, for example, Reinhardt found that democracies are more disputatious overall; they are both more likely to initiate disputes before the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), as well as to be targeted by other parties (regardless of the complainant's regime type).Footnote 79 Similarly, Sattler and Bernauer conducted a statistical analysis which found that “domestic politics appears to be very important for dispute initiation and is, arguably, more important than economic power and trade dependence. More democratic countries are much more likely to become involved in trade disputes. Democratic countries both initiate significantly more trade disputes and also become the target of a dispute significantly more often.”Footnote 80 Pelc, studying investment law using his own data, found that ISDS cases disproportionately target democracies rather than autocratic regimes with weak rule of law.Footnote 81 He found that 64 percent of disputes in the last two decades involved democracies, consistent with the data in Table 4. In terms of human rights, Bernard Boockman and Axel Dreher showed that democracies were more likely to support UN human rights resolutions than nondemocracies.Footnote 82 Cosette Creamer and Beth Simmons demonstrated that democracies submit higher quality reports to human rights monitoring bodies (though may be no more likely to report in general).Footnote 83

The evidence presented in this Part shows that, consistent with the theory laid out in Part II, democracies are more likely to utilize international law to engage in cooperation and conflict resolution than are authoritarians. But the evidence on international organizations, in which authoritarian participation seems to be increasing, suggests that there is some change afoot and that authoritarians are cooperating in more sophisticated ways. I now turn to this phenomenon.

IV. The Evolution of Authoritarian International Law: From Use to Normative Development

This Part starts with an analogy from the study of national constitutional orders. As my colleagues and I at the Comparative Constitutions Project showed in a 2014 paper, there are many similarities between formal constitutions adopted in democracies and those in dictatorships.Footnote 84 That work finds that most innovations in constitutional technology occur in democracies, but that authoritarians borrow these innovations in a lagged manner. When it comes to national constitutions, the scholarship indicates that that democracies innovate and authoritarians mimic and repurpose.Footnote 85 The mechanism is that democracies confront governance problems and create new institutions such as rights to information, independent electoral commissions, and ombudsmen. As these institutions diffuse to other countries that are drafting constitutions, dictatorships mimic them. But with their laser-like focus on survival, dictators quickly learn to undermine the integrity of these institutions, and so the formal similarity masks differences in function. The purpose of the borrowing may be to enhance legitimacy by appearing democratic, but it also allows authoritarians to experiment with new institutions that can help extend their rule. Regardless of the goals, scholars have seen gradual convergence of form across regime type over time. The increasing use by authoritarians of institutions that originate in democracy—for example, elections, judges with some degree of autonomy, counter-corruption commissions, and long lists of rights—suggests that mimicry may be some benefit for authoritarian survival.

This borrowing and retooling can help facilitate “adaptive authoritarianism.” This phrase originates in the study of Chinese politics, and is a characterization that seeks to explain the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) surprising resilience and stability over the past few decades.Footnote 86 While some scholars have argued that the CCP would inevitably democratize,Footnote 87 studies of adaptive authoritarianism counter this view by offering a robust account of how the CCP's regime will remain resilient into the future. According to some scholars, the adoption of new institutional innovations—including administrative law, freedom of information, and village elections—has allowed the regime to weather significant challenges.Footnote 88 With the increasingly authoritarian turn under Xi Jinping's leadership, these scholars seem to have the upper hand in the argument.

Might the use of international law follow a similar logic? Could authoritarians be retooling the machinery of international law to suit their own ends and help extend their rule? This Part provides evidence of gradual learning by authoritarian regimes and an evolution from formal mimicry to more sophisticated engagement with the machinery of international law. The focus is on regional organizations as important sites of cooperation and normative development. I begin with examples of authoritarian mimicry, including the Warsaw Pact, ASEAN, and the Eurasian Economic Community. I then turn to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Mimicry: The Warsaw Pact

In 1955, a group of communist countries concluded a mutual defense treaty, six years after the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).Footnote 89 A significant characteristic of the Warsaw Pact was that it was fundamentally reactive in nature. The treaty was conceived as a response to what the Soviet Union perceived as the encroaching influence of NATO; and, more specifically, to the inclusion of a remilitarized West Germany in the alliance.Footnote 90 These political conditions were so central to the precipitation of the Pact's formation that they were written into the text of the treaty itself. The treaty's very first line affirms the importance of a collective security regime “irrespective of social and political systems,” likely an implicit jab at NATO's rebuffs of the Soviet Union's attempts to join it in 1954.Footnote 91 The same line goes on to explicitly reference as the treaty's motivation the “situation created in Europe by the ratification of the Paris agreements, which envisage the formation of a new military alignment in the shape of ‘Western European Union,’ with the participation of a remilitarized Western Germany and the integration of the latter in the North-Atlantic bloc.”Footnote 92

In the (relatively brief) text of the treaty itself, the Warsaw Pact established certain obligations that were incumbent on its members, mirroring those of the NATO treaty. These obligations included a commitment to settling intra-Pact disputes peacefully, and without the use of force (Article 1); a commitment to nuclear disarmament (Article 2); the establishment of a collective security regime under which all parties to the Pact will come to the assistance of any party under armed attack (Articles 3 and 4); the establishment of a Joint Command of the armed forces (Article 5); and the establishment of a Political Consultative Committee (Article 6). The treaty closes with the stipulation that the Warsaw Pact would dissolve in the event that a pan-European system of collective defense is ever established.

In terms of the obligations and costs it imposed on its member states, the Warsaw Pact was modeled on the NATO treaty.Footnote 93 Perhaps the most explicit and substantial obligation was the commitment to collective self-defense. In an interesting contrast with the Warsaw Pact treaty, the NATO treaty explicitly stipulates that “this Treaty shall be ratified and its provisions carried out by the Parties in accordance with their respective constitutional processes,”Footnote 94 which for some of them would involve legislative approval. There was no such demand for legislative ratification in the Warsaw Pact treaty, which lacked what international organizations scholars call vertical enforcement—there were no domestic mechanisms designed to promote compliance.Footnote 95 The barely hidden subtext was that the Pact did not really need domestic democratic approval to make it enforceable, as the shadow of Soviet power was the real force at work. In contrast, NATO members were invited to affirm the treaty obligations through national processes, which would presumably involve deeper commitment.

The life of the Warsaw Pact was in fact quite different from that of NATO. Whereas the latter involved a series of subsequent agreements and protocols, as well as disagreements among members, the Warsaw Pact was not a vital legal regime.Footnote 96 Instead, it was a tool for Soviet domination of member states to ensure continued communist rule. Although the Pact promised “respect for the independence and sovereignty of states” and “noninterference in their internal affairs,”Footnote 97 when the provisional revolutionary government of Hungary declared its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact in 1956, Soviet troops invaded.

In addition, the Warsaw Treaty Organization was dissolved at the end of the Cold War, whereas NATO began to engage in collective military action in its aftermath. It expanded from twelve original members to twenty-nine current members. In the 1990s, NATO took military action in Bosnia and Kosovo; and in 2001, after the 9/11 attacks, it invoked the collective self-defense provisions of Article 5. In short, the legal obligations of NATO played some role in its life, whereas this was not the case for the Warsaw Pact. The Warsaw Pact was, largely, form without function, but it illustrates an international legal regime designed to maintain and extend authoritarian rule.Footnote 98

Sovereignty-Reinforcing Regionalism: ASEAN

Another example of authoritarian use of international law, albeit more functional than the Warsaw Pact, is ASEAN). Founded in 1967 by five countries, ASEAN later expanded to six countries with the addition of Brunei in 1984, and eventually ten countries after the end of the Cold War. It was an authoritarian international organization in the sense that none of its members were democracies; only the Philippines could be considered partly democratic at the time of its founding. Even today, only Indonesia can be considered a stable democracy, though Malaysia seems to be moving in that direction. But as originally conceived, ASEAN was designed to bolster relatively weak states and thus consolidate authoritarian rule.

ASEAN has gradually developed more significant programs of regional integration, most significantly in the 2007 adoption of the ASEAN Charter.Footnote 99 It now encompasses an ASEAN Economic Community), a (very weak) human rights institution, and the ASEAN Regional Forum which is a security structure bringing together most of the countries with security interests in the Asian region. However, integration is not deep in either the economic or political spheres, especially when compared with regional organizations in Europe and Latin America.Footnote 100 The region's economies are disparate in development levels and ambitions for legal integration are moving slowly. ASEAN is only weakly institutionalized in that its organs and process have little independent effect on outcomes of the region.Footnote 101

Instead of promising “an ever-closer Union,” the ASEAN Charter emphasizes the traditional principles of noninterference, sovereignty, and independence.Footnote 102 This in turn drew on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, articulated by India and China in 1954 and reiterated at the Bandung Conference of 1955: (1) mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; (2) mutual nonaggression; (3) mutual noninterference in internal affairs; (4) equality and mutual benefit; and (5) peaceful coexistence.Footnote 103 These principles—essentially Westphalian in character, but neither democratic nor authoritarian in essence—reflected the need for newly decolonized states to focus on the prerogatives of state-building.

Noninterference has guided ASEAN from its earliest days; above all, ASEAN's regionalism is sovereignty reinforcing. Sovereignty-reinforcing regionalism served the interests of state-building in a region where borders were largely determined by colonialism, and where each country is multiethnic. In places such as Mindanao, Pattani, Kachin State and Aceh, local demands for autonomy or even secession remain vital, and were even more stark in the early years of independence. Noninterference in ASEAN was not merely rhetorical, but meant that states had to refrain from openly supporting national liberation movements in their neighbors. In the early phases of state-building, the mutual commitment meant something real, and the lofty rhetoric of Bandung was deployed to help extend regime survival.

The “ASEAN Way” refers to a process of consultation and consensus, sometimes identified with many of the cultures in the region. It has meant that there was no regional criticism of the Khmer Rouge, the Burmese Junta, or Indonesia's occupation of East Timor. ASEAN's Westphalian style of regionalism is one in which political leaders gather to discuss mutual concerns but refrain from criticism and genuinely leave each other's “internal” affairs alone. This point is worth highlighting, particularly because of the claims of liberal international lawyers in the 1990s. There is plenty of “New World Order”-style cooperation among ASEAN bureaucrats, who have advanced a number of modest programs for educational and cultural cooperation, but there is neither deep integration nor much of a shift from classical Westphalian international law.

Increasingly, international legal cooperation within ASEAN has been utilized to defend authoritarianism in the member states. Cambodia's Hun Sen banned the main opposition party, the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP), in 2017, en route to a complete victory in 2018 elections. When CNRP leaders sought to travel to Phnom Penh to engage in protests in November 2019, neighboring Thailand and Malaysia invoked the ASEAN principle of noninterference to bar their travel.Footnote 104 Cambodia also sought (unsuccessfully) extradition from Malaysia on trumped-up charges against CNRP Vice-chair Mo Sochua.Footnote 105 Thailand has extradited other Cambodian activists, including a woman whose crime was throwing a shoe at a ruling party billboard.Footnote 106 At the same time, other extradition requests have been rejected, and a Model ASEAN Extradition Treaty retains a good deal of discretion for state parties who are requested to turn over fugitives, in keeping with the overall emphasis on state sovereignty of the regional organization.Footnote 107

Partial Institutionalization: The Eurasian Economic Union

In 2014 Belarus, Russia, and Kazakhstan signed a treaty establishing the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), subsequently joined by Armenia and Kyrgyzstan.Footnote 108 The EAEU emerged as the culmination of a process of gradual integration that grew out of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and absorbed a separate initiative called Central Asian Economic Cooperation. The EAEU's goals and institutional development have followed the pattern of the European Union, beginning with a Eurasian Economic Community (2000), a customs union (2007), and a single market (2012), before the full-fledged “Union” emerged. The EAEU structure mimics the European Union with a Supreme Council composed of the heads of state, an Intergovernmental Council composed of the prime ministers, a Court of Justice, and a Eurasian Economic Commission, which is an executive branch of bureaucrats, similar to the European Commission. The annual budget is roughly $10 million, and it has approximately 1,200 employees whose positions are allocated in accordance with the overall population share of the member states. It does not yet, however, have a parliamentary body or common currency, although both have been broached.

The EAEU has also adopted the language of “enlargement,” and has concluded several free trade agreements, including with neighboring Ukraine, Moldova, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan in the CIS Free Trade Agreement.Footnote 109 The only two additional countries to join as full members, interestingly, were hybrid regimes, Armenia and the Kyrgyz Republic. These countries were invited to membership in reaction to the “Eastern Partnership” of the EU European Neighborhood Policy, which had targeted these nations.Footnote 110 In this sense, the deployment of international cooperation was motivated by a defensive strategy to prevent neighboring states from moving too much into the Western democratic sphere.

Unlike many other international organizations created by authoritarian governments, but like the European Union, disputes are resolved by a judicial body. The current iteration, the Court of the Eurasian Economic Union, followed the CIS Free Trade Area Court, the economic court of the CIS and a Court of the Eurasian Economic Community. Following the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union, the new Court was set up in 2015, without legal continuity carrying over from prior courts.Footnote 111 None of these courts have been particularly busy; there were only thirteen interstate disputes in its first twenty years of operation of the CIS Court, but the tribunal was called upon regularly (more than one hundred times) to interpret CIS acts and agreements.Footnote 112 Many of these cases are brought by the organs and civil servants of the organization. This suggests a body with some functional role beyond a mere talk shop for heads of state. The EAEU, from this point of view, reflects the greater sophistication of institutional form, even if it involves mimicry of the democratic innovations of the European Union. At the same time, the Court's ambit is limited and there is no chance of it becoming a major engine of legal development like the Court of Justice of the European Union.Footnote 113 The Statute of the Court is explicit that: “No decision of the Court may alter and/or override the effective rules of the Union law and the legislation of the Member States, nor may it create new ones.”Footnote 114 Instead, an EAEU court finding that the Commission's decision is not in line with the Treaty or international treaties within the Union has no legal effect unless accepted by the Commission or Council.Footnote 115 This is an executive-centered international organization, which it is impossible to imagine evolving into a constitutional federalism of the European type, in which international organs can constrain the member states themselves. However, the overall organization has had some real, if limited, impact in expanding market access and in solidifying a customs union among its members.

Toward Cooperation: The Shanghai Cooperation Organization

Like the CIS and the Central Asian Cooperation initiative, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) was originally formed as a response to the collapse of the Soviet Union, acting as a forum to demarcate borders between China and its new post-Soviet neighbors. Founding members were the so-called Shanghai Five—China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan—with Uzbekistan joining in 2001. In 2001, this cooperative forum was formalized and branded as the SCO. China played a leading role, sponsoring a process to gain observer status for the SCO in the UN and a resolution at the General Assembly on UN-SCO cooperation.Footnote 116 The scope of the organization's goals broadened significantly to encompass counterterrorism efforts aimed at curbing extremism as well as regional economic initiatives and energy cooperation. It is not, however, a military alliance or directed against extraregional threats, which enabled India and Pakistan to join the organization in 2017.

The SCO operates via several core structures: annual head-of-state summits, more frequent meetings among foreign ministers, the Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure (RATS), and a Secretariat. It has recently begun cooperating in joint exercises to combat cyber terrorism.Footnote 117 However, the independent power of this institutional infrastructure is questionable at best. Most observers have been skeptical of its achievements. One scholar views the SCO as no more than a “weak multilateral framework” for coordinating regional policies between its members, questioning its efficacy as an autonomous body in its own right.Footnote 118 He argues that most of the deals and initiatives brokered under its auspices consist of bilateral deals that probably would have happened even if the SCO never existed; the SCO provides only a “convenient negotiating venue.”Footnote 119 Others deride the SCO as “more of a private club” than a competent multilateral body and “more form than substance.”Footnote 120

The organization's most prominent public events, like the annual summits and joint military exercises, are paid for by member states directly.Footnote 121 Thus, the SCO does not possess any meaningful financial autonomy from its member states, which often foot the bill for organizational activities.

While the institutional structure of the SCO is ultimately quite weak, leaving much room for the individual interests of its member states to take precedence, it has played a role in the normative development of authoritarian international law in its active identification of the “three evils”—terrorism, separatism, and extremism—as targets for cross border cooperative repression. These will be elaborated in the next Part. The SCO has also introduced a subtle rhetorical shift in focusing on the “rule of international law,” which reinforces sovereignty and consent, rather than the thicker concept of the international rule of law pushed by some democracies.Footnote 122 The latter phrase implies extending rule of law values— accountability, equality, and fairness—to the international level.Footnote 123 The rule of international law instead emphasizes traditional Westphalian values such as the faithful observance of international norms.

One of the international law innovations of the SCO is that some of its norms are supposed to guide the member states’ behavior with respect to other treaties.Footnote 124 As a general matter, the SCO does not impose substantive constraints on the ability of its member states to join other international legal instruments and organizations, rendering its own authority over its members quite weak and leaving them free to participate in other treaty regimes. The SCO conflict clause, for example, states that in the event an obligation imposed by an SCO document conflicts with a provision in another international treaty, the provisions in the other treaty take precedence. However, there is an exception that prohibits parties from concluding other treaties that run counter to the SCO treaties; these clauses appear most frequently in SCO treaties concerned with the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism.Footnote 125 This suggests that a treaty that sought to recognize, for example, a claim of secession by a member's substate would be void under the terms of the SCO treaties.

By enhancing domestic and cross-border security cooperation, the SCO allows its member states to reduce the possibility of regime change and to bolster authoritarian principles through multilateral cooperation.Footnote 126 This rhetoric is partly defensive, a way of combating the threat of democracy-promotion by delegitimizing democratic principles.Footnote 127 Democracy is not mentioned, however, so the SCO does not fall into the category of pure mimicry. Instead, by emphasizing the value of stability and pluralism, the SCO can be understood as a way for its member states to shore up the legitimacy of their authoritarian regimes and insulate them from democratization pressures.

As in many treaties among authoritarian regimes, and consistent with the theory laid out in Part II, there is no delegation to a third party to resolve disputes in SCO agreements. Instead, the preferred approach to dispute resolution is negotiation and consultation. This facilitates coordination by executives.

The pattern of norm-building activity in the SCO will sometimes fall in a sequence, with a “concept” followed by a “program,” followed by a “plan,” with each iteration becoming more detailed in the cooperation that is required. The instruments are also notable for referring to UN documents, such as General Assembly Resolutions. This is part of a growing strategy by leading authoritarian nations to engage with the UN machinery, along with other international organizations such as the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Collective Security Treaty Organization. In this sense, the SCO is projecting regional norms onto a broader international arena, contributing to more global normative development.

The SCO as Harbinger

The SCO can be considered a critical step in the development of authoritarian international law in the twenty-first century in another respect—it has served a vehicle for China to test its own approach. Some analysts have argued that the SCO has been hampered by the geopolitical competition between its two most powerful members, Russia and China.Footnote 128 Still, there is much common ground between Russia and China on the nature and use of international law. In 2016, the two countries issued a joint Declaration on the Promotion of International Law.Footnote 129 This statement reaffirmed the traditional touchstones of sovereignty and nonintervention, such as the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, the UN Charter, and the 1970 Declaration on the Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States.Footnote 130 While committing to the peaceful settlement of international disputes, the Declaration reaffirms the importance of consent and good faith, a position that “applies equally to all types and stages of dispute settlement.”Footnote 131 One might read this as requiring specific consent to each instance of dispute resolution. It also specifically mentions UNCLOS and the requirement of consistent application of its provisions, “in such a manner that does not impair rights and legitimate interests of States Parties”Footnote 132—a veiled reference to the South China Sea Arbitration that was ongoing at the time and to which China never gave specific consent over ITLOS jurisdiction.Footnote 133 The statement also condemns terrorism, unilateral sanctions, and coercive measures outside the context of the Security Council process, and reaffirms state immunity.

Though sounding in classical Westphalian sovereignty, the Russia-China statement is in fact more sophisticated and reflects a good deal of learning and experimentation by authoritarian leaders toward extending their own rule and reinforcing each other. A changing balance of power in favor of authoritarians will give these countries greater weight in the formation of international law generally, as well as the ability to deploy specific strategies within the field.

China, in particular, will have an outsized role, given the size of its economy and its global ambitions under President Xi Jinping, who has emphasized “win-win” (共赢- “gong ying”) foreign policy, “mutually beneficial cooperation,” and “a Community of Shared Future for Mankind.”Footnote 134 China is promoting these concepts in its increasingly assertive role in international organizations, especially the United Nations, where it is embedding its ideas into resolutions and initiatives.Footnote 135 This more active multilateralism coincides with China becoming “increasingly flexible toward the Westphalian norms of state sovereignty and non-intervention.”Footnote 136 China is also more prepared to redefine its interests and accept costs, except in matters related to human rights, humanitarian intervention, and self-determination, which could threaten domestic regime stability.Footnote 137

It is not only at the level of rhetoric in which authoritarians are softening their Westphalian stance. One way in which Russia and China have moved beyond the noninterference principle is their increasingly complex strategies of supporting “rabble-rousing” inside other countries.Footnote 138 These activities includes election manipulation, creating “fake news,” and espionage.Footnote 139 Authoritarians also use international organizations to provide direct support for authoritarian allies in neighboring countries. When Daniel Ortega was consolidating his control of the Nicaraguan political system in the run-up to elections in 2015, he borrowed several strategies from Hugo Chávez but also obtained support from the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), which invested funds in a Nicaraguan television station to ensure its support for Ortega.Footnote 140 The legal framework of ALBA facilitated the undermining of a free press in a hotly contested election.

These activities of cooperating for mutual support and interfering in the internal affairs of other countries, however, do not address the content of authoritarian international law, as distinct from pro-democratic or regime-neutral international law. The next Part of this Article turns to nascent normative developments pushed by authoritarian regimes.

V. Beyond Westphalia: The Content of Authoritarian International Law

This Part offers three examples of ways in which a growing authoritarian role in the international arena may affect the normative content of international law: the development of new norms to facilitate internal repression, regulation of cyberspace, and the dilution of democratic concepts and institutions. These examples are illustrative, not exhaustive, but they give a flavor of the directions authoritarian international law might take.

New Norms: Extremism and Separatism

Of the organizations surveyed in Part IV, the SCO has been the most advanced in articulating new international norms, particularly in its elaboration of the “three evils” discussed above—terrorism, separatism, and extremism. These terms received further elaboration in a SCO Convention on Countering Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism of 2001 (which entered into force in 2003), and subsequent instruments.Footnote 141 The definition of terrorism largely mimics the global definition elaborated in numerous multilateral treaties, but separatism and extremism are new concepts on the international plane.Footnote 142 Separatism refers to any act to violate territorial integrity or directed at state disintegration.Footnote 143 Extremism is defined as “an act aimed at seizing or keeping power through the use of violence or changing violently the constitutional regime of a State, as well as a violent encroachment upon public security, including organization, for the above purposes. …”Footnote 144 The term has been invoked recently, for example, with regard to the demonstrators in Hong Kong.Footnote 145

A separate Convention on Counter-Terrorism was adopted in 2009, and a Convention on Countering Extremism was signed in June 2017.Footnote 146 Both of these more specific treaties expand the relevant definitions of these concepts, extending them beyond “acts” to include “ideology and practice.” Both commit states to criminalize, punish, and cooperate in the prosecution of violators, along the lines of the various global treaties on terrorist acts.Footnote 147 Cooperation to counter extremist financing is also included in the latest treaty. Together they form the basis for joint SCO action against “societal radicalization.”Footnote 148

These norms represent an evolution from existing law. Criminalizing advocacy of separatism is in some tension with the international norm of self-determination, as traditionally understood. That norm does not generally provide a right to external self-determination in the form of secession.Footnote 149 But many argue that it includes an exception in instances of severe oppression of rights to internal self-determination, a position given some support by the Supreme Court of Canada in its decision on Quebec's secession referendum.Footnote 150 The ICJ's cautious advisory opinion in the Kosovo case refrained from specifically endorsing this exception.Footnote 151

At a moment of heightened demands for secession around the world, the SCO norm against separatist ideology on a regional level has important implications. It demonstrates that states may go quite far in punishing freedom of expression if it is designated as “secessionist,” which in turn hampers the ability of an oppressed group to raise awareness of their conditions to the international plane. This may undermine the consolidation of the “oppression exception” articulated by the Supreme Court of Canada and affirmed by advocates of the Kosovo Declaration of Independence.

Extremism, too, is a new and vague term. To introduce it implies a separate “evil” not currently covered by terrorism or separatism. Thus, extremism goes beyond acts of violence directed at changing state policy, as those would fall under conventional definitions of terrorism. The explicit focus on “seizing or keeping power” suggests that it is narrowly targeted at violent political action directed at state authorities. While there is surely a difference between peaceful mobilization for democratic change and violent action, the line is fuzzy in the context of an authoritarian regime. One might imagine that demonstrations such as those that recently triggered constitutional change in Chile or Panama, which were by and large peaceful but did involve some violent elements, would trigger wholesale repression, mutually supported by neighbors, were they to occur in an SCO country.Footnote 152