Introduction

In the last ten years, a new model of business-to-business statutory arbitration has emerged: the ‘code adjudicator’. These are Janus-faced government appointees combining, as Hodges puts it, ‘elements of dispute resolution and of public quasi-regulatory authority’.Footnote 1 On the one hand, they discharge a statutory arbitration role in contractual disputes between regulated parties governed under s 94 of the Arbitration Act 1996. On the other, they discharge a regulatory role investigating compliance with a statutory code, bolstered with a power to issue sizable fines for breaches. The first of their kind are in the UK. The Groceries Code Adjudicator deals with contractual disputes between the largest supermarkets and their suppliers and the Pubs Code Adjudicator (PCA) deals with disputes between the largest pub-owning companies and their tied tenants.Footnote 2 Modelled on these two entities, others have called for ‘code adjudicators’ to preside over dealings between landowners and mobile or broadband network operators,Footnote 3 between small businesses and digital platforms such as Amazon and Google,Footnote 4 to enforce codes of conduct in the energy sector,Footnote 5 or – as raised recently in the House of Commons – for a ‘Garment Code Adjudicator’ to ‘to reduce exploitation in the UK's garment industry’.Footnote 6 These ‘new intermediaries’Footnote 7 in business-to-business dispute resolution are a much-touted solution for regulators faced with large businesses exploiting their power over small businesses.

This paper is a detailed critique of the most active of the ‘code adjudicators’: the PCA, established under the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 and presiding over the Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016, SI 2016/790. Drawing on a database of arbitration decisions, data on the exercise of code rights, interviews with affected tenants and legal analysis of referrals to the High Court under s 68 and s 69 of the Arbitration Act 1996,Footnote 8 we argue that the PCA and the operation of the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 suffer from a series of limitations, reflecting both shortfalls in their underpinning regulations and broader issues that arise with the ‘code adjudicator’ model. In particular, we highlight problems of delaying tactics, ‘burden of proof’ standards, and interactions with prior legal relationships (in this case, that of a landlord and tenant). Fundamentally, as Hodges argues, any model of dispute resolution has two core objectives: (i) to identify problems and resolve them, and (ii) to change future behaviour or systems based on problems its users encounter.Footnote 9 We argue that the current operation of the PCA and the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 currently fails on both counts.

The argument is in three sections. First, we provide an outline of the longstanding problem that the creation of the PCA was designed to address – the vertical integration of ‘tied pub’ businesses and the resulting power imbalance between large pub-owning companies (PubCos) and their tied leaseholders. It is not possible to understand the development and current operation of the Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016 without understanding how the sector has developed and previous attempts at legislative intervention. This section draws on archival research – all references to archival material derive from records held in the National Archive, Kew, London. Secondly, we provide a precis of the PCA's powers and underpinning regulations. Thirdly, drawing on arbitration data, interviews with affected tenants and legal analysis of appeals under the Arbitration Act 1996, we argue that this case study of the PCA reveals significant shortcomings in both the current design and operation of the Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016 and the ‘code adjudicator’ model more broadly.

1. Tied pubs as a regulatory target

Though often discussed with misty-eyed references to ‘English cultural history’Footnote 10 or their ‘magic and majesty’,Footnote 11 public houses are longstanding legal battlegrounds. This is especially true of pubs operating under the ‘beer tie’ model, accounting for nearly half of the UK's approximately 45,000 establishments. This tied model has been central to the pub sector across several European countries since at least the nineteenth century, imposing obligations on the leaseholders (the pub landlords, often also living in the property) and securing a route-to-market for the freeholders, traditionally the breweries themselves and more recently the modern ‘pub owning company’.Footnote 12

The proposition is simple: in return for reduced rent and business support, the tied tenant's procurement is constrained under the lease through a contractual arrangement of exclusive supply. These restrictions on procurement – known as the ‘wet rent’ – require the tenant to purchase beer and often wines, spirits, soft drinks and other supplies from the owner of the establishment. These products are provided at a higher-than-market cost, with the Office for Fair Trading estimating that in the UK the price of beer is on average 30% higher under a tie (with other organisations arguing the differential is far higher),Footnote 13 and restrict the tied tenant's purchasing power to a finite list of PubCo approved products.

This ‘beer tie’ model is defined by two features. First, there is a ‘risk transfer’ between the PubCo and the tied tenant.Footnote 14 The cheaper ‘dry’ rent on the property, offset against the ‘wet’ rent on constrained procurement, is ordinarily calculated in line with the estimated turnover a competent publican can fashion, known as the ‘fair maintainable trade’. The rent in the lease reflects a division of estimated profits – known as the ‘divisible balance’ – ordinarily in the region of 65% to the PubCo and 35% to the tied tenant. For the tied tenant, the estimated turnover is therefore baked into their rent: they carry the risks of failing to meet the PubCo projections. Tenants who over-perform these estimates buy more tied beer, and as a result pay more ‘wet’ rent to the PubCo. This is perhaps reflected in differential earnings between tied publicans and their non-tied counterparts. The IPPR have found that 46% of tied publications earn less than £15,000 per year – more than double the proportion of non-tied publicans.Footnote 15

Secondly, in addition to providing a notionally cheaper ‘dry’ rent, PubCos argue that tied tenants have access to the valuable provision of business services and advice. In a competition law sense, these are ‘special commercial or financial advantages’, such as training, public relations provision, marketing and business advice.Footnote 16 This is more than just business acumen: a fundamental principle of competition law within such vertically integrated models is that exclusive purchasing obligations are offset by countervailing benefits.Footnote 17 The vertical integration of the tied model has been subject to a series of references by brewers to the EU Commission which have dealt specifically with this issue, concluding that such ties can be ‘more than offset by quantifiable countervailing benefits’.Footnote 18 The usefulness of these commercial and financial advantages – especially when set against the comparative high costs of the ‘wet’ rent – has been criticised by campaigning organisations and tied publicans.Footnote 19

(a) Failed regulatory interventions

This vertical integration of production and supply is evergreen in the British pub sector. As far back as 1795, Colquhoun's report Observations and Facts Relative to Public Houses critiqued the dominance of the tied model, with large regional brewers ‘actively engaged in buying up properties which they then rented back to tenant landlords’.Footnote 20 Indeed, disputes over tied leases were emerging in the civil courts with some frequency from the late eighteenth century onwards. A particular concern for tied publicans was being forced to buy beer through the tie that was stale or of poor quality. In Holcombe v Hewson Footnote 21 the publican argued successfully that he should be able to break free of the tie in his lease as the beer supplied was so ‘very bad’ that ‘he had lost almost the whole of his customers’.Footnote 22 What is striking about these decisions is the judges’ clear criticism, even at this early stage, of the impact of tied leases on their tenants. This is perhaps best illustrated in Thornton and Others v Sherratt Footnote 23 – another case where a publican was sold ‘stale’ beer under the tie.Footnote 24 In his judgment, Chief Justice Robert Dallas underscores that he ‘very much disapprove[s] of these covenants by which the brewer gets the publican into his power’,Footnote 25 and Justice Burrough concurs, stating that the ‘contracts by which brewers bind publicans to deal with them are not to be favoured’ as they are ‘very prejudicial to the health of the subject’.Footnote 26

The current market is scarred by a series of failed regulatory interventions attempting to tackle the problem. Perhaps most infamously, the Beerhouse Act 1830 (also referred to as the ‘Beer Act’) was a failed attempt to crush the monopoly of a heavily vertically integrated beer sector. Indeed, Yeomans suggests ‘its very name became synonymous with regulatory failure’.Footnote 27 Mindful of the concerns of Colquhoun's report and the stranglehold on the beer sector by powerful regional brewers, legislators sought to open access to what had traditionally been both a restrictive licensing system for pub operators and a hard-to-access brewing market for new entrants. As Nicholls highlights, this laissez faire intervention in the brewing industry was in vogue, with contemporaries noting that ‘it was an obsession of every enlightened legislator’ between 1820 and 1830 that ‘cheapness and good quality could only be secured by an absolutely unrestricted competition’.Footnote 28 The resulting Beerhouse Act 1830 removed the requirement for a licence granted by magistrates altogether for those seeking to sell beer and cider. Now, for a small annual fee of two guineas, anyone could brew beer and sell it from their homes.Footnote 29

Within six months of the Act coming into force, over 24,000 beer shops had opened under the new provisions, joining 51,000 premises that were already licensed. This rose to 46,000 additional venues by 1838, effectively doubling the number of places across England and Wales where one could drink beer.Footnote 30 Perhaps unsurprisingly, this led to moral outrage among the ruling classes, who considered that these reforms had ‘touched off an irreversible course of working-class drunkenness’.Footnote 31 The regulatory experiment was short-lived and in 1869 magistrates were brought back to preside over the licensing of establishments under the Wine and Beerhouse Act 1869, with restrictive supply – and associated vertical integration by the brewers, delivered through tied leases – strengthening.

What followed were a series of failed attempts to pass legislation to address the prevalence of tied arrangements within the pub sector. Evidence presented to the Royal Commission on Licensing for England and Wales from 1929 to 1931 – a time when around 90% of public houses were tiedFootnote 32 – is particularly instructive of the concerns. Tied tenants providing evidence in front of the committee spoke of the brewers and tied tenant relationship as akin to ‘a tyrannical master and a very helpless servant’, as tied tenants shouldering ‘all the work and all the worry, and the brewers the profit’,Footnote 33 and – most colourfully – one described the ‘brewer as an “octopus squeezing the life out of the licensee”’.Footnote 34 The Commission decided against recommending abolition of the tie, echoing evidence from one brewer that it is ‘far too deeply rooted to permit any hope of its abolition’ and another, that the practice is ‘inevitable’.Footnote 35

Notwithstanding the Commission's reluctance for legislative reform, the early twentieth century is littered with unsuccessful Bills seeking to abolish or constrain tied arrangements. Most notably, the Tied Houses (Freeing) Bill in 1902 and the Tied Houses (Abolition) Bill 1906 were (unsuccessfully) introduced to the House of Commons in an attempt to prevent breweries holding alcohol licences on behalf of their tenants.Footnote 36 Unperturbed, the Licensing Law Reform League continued to argue for a Freeing of Tied Houses Bill until the 1940s.Footnote 37 These unsuccessful legislative attempts were accompanied by equally unsuccessful legal action. The enforceability of lease covenants imposing the tie were challenged routinely within the courts across the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the sector boomed, and were as routinely upheld.Footnote 38 Indeed, in their analysis of an unreported challenge in Mablethorpe Hotels Ltd v Home Brewery Cod Ltd in 1937, the Brewing Trade Review lamented that ‘the validity of tying covenants has never been seriously questioned’ by the courts, with the judgment in Mablethorpe ‘showing how well-established that validity is’.Footnote 39

This status quo was left largely untouched until the so-called ‘Beer Orders’ of the late 1980s: the Supply of Beer (Loan Ties, Licensed Premises and Wholesale Prices) Order 1989, SI 1989/2258, and the Supply of Beer (Tied Estate) Order 1989, SI 1989/2390. As Nicholl's argues, these instruments were motivated by strikingly parallel concerns to the Beerhouse Act 1830.Footnote 40 By the 1960s, control of UK brewing and the pub stock by the largest six breweries had become difficult to ignore. More than 80% of the UK pub sector was under direct brewery control, and 97% of beer produced in the UK was sold in outlets owned by the brewers themselves.Footnote 41 This led to a sustained interest by regulators and competition authorities in the wake of the Second World War, starting with a refusal to grant an increase in prices by the National Board for Prices and Incomes,Footnote 42 prompting the first investigation by the Monopolies Commission in 1969.Footnote 43 This concluded that, ‘but for the difficulties of change and transition’, a system not reliant on the tie was ‘preferable’ to the current state of affairs.Footnote 44 Such concerns were soon superseded by a second inquiry by the Monopolies Commission in 1989, triggered by report from the Price Commission and a reference from the Office for Fair Trading.Footnote 45 They concluded that a complex monopoly existed and regulatory action followed in the form of the ‘Beer Orders’. Among many other interventions, such as the requirement to allow operators to carry at least one guest cask-conditioned ale,Footnote 46 the Orders required breweries to reduce their tied estates to 2,000 or fewer licensed premises.Footnote 47

The Beer Orders are an example of regulatory unintended consequences par excellence. The main result of the policy was a second model of vertical integration based on ‘PubCos’: financial intermediaries and pub-owning companies to whom the breweries’ decanted their tied estates.Footnote 48 Indeed, although the number of tied pubs fell by over 30% as a result of the Beer Orders, as Nicholls argues, that was offset ‘almost precisely’ by the rise of PubCo establishments engaging with an ever-concentrated brewing industry.Footnote 50 The largest breweries were boasting publicly that they were still retaining over 70% of beer sales in pubs that they had divested.Footnote 51 As Hilton notes, many of the most self-proclaimed ‘pro-business politicians’ had inadvertently ushered in a series of unintended consequences that have shaped the sector to the detriment of many operators.Footnote 52 The orders were revoked in 2003, as – in the words of the Government at the time – ‘there is nobody to whom the orders are currently relevant… it is a pointless regulation’.Footnote 53

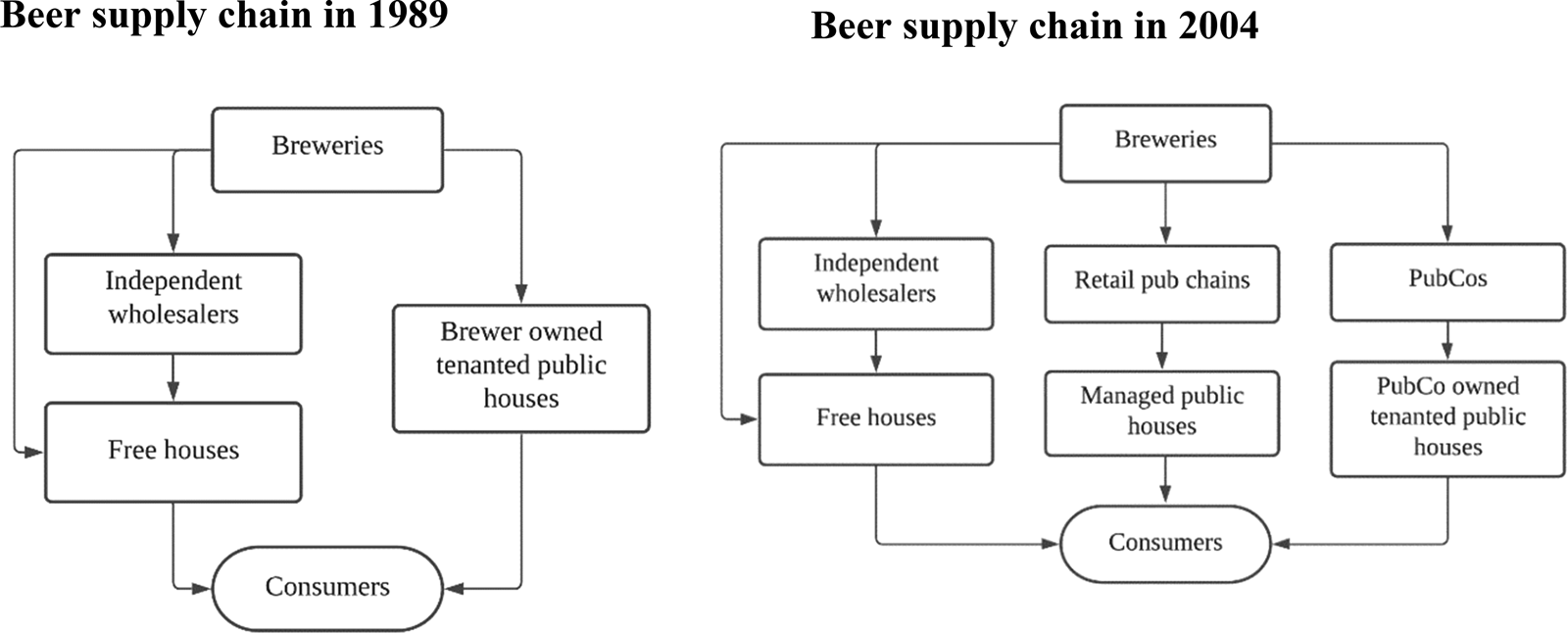

What emerges, therefore, is a complex beer market with PubCos, independent pubs, and other tied or retail chain public houses, all regulated differently. Figure 1 provides a brief summary of the construction of the pub sector as it currently stands, as compared to the beer supply chain of the late 1980s for pubs subject to the Beer Orders intervention.

Figure 1. The beer supply chain in 1989 and in 2004, adapted from the Select Committee on Trade and IndustryFootnote 49

Clearly, the concern of this paper – the PCA and the Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016 – can only be understood alongside these changes in the beer and pub market and the consequences of previous failed attempts at regulatory intervention. Indeed, PubCos themselves are a creature of unforeseen consequences of the Beer Orders of the late 1980s. Having established this important context, the next section moves to the development of the PCA model itself.

(b) The origins of the Pubs Code Adjudicator Model

As a result of these industry shifts, the focus of the debate has moved from anti-competitive practices by the breweries to those of the newly formed PubCos. There were a wide-range of complaints by tied tenants: that the cost of beer (the ‘wet’ rent) was too high; broader-ranging exclusive purchasing agreements were anti-competitive; and PubCo support – particularly given the high combined costs of the ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ rent, was left wanting.Footnote 54 Concerns led to no fewer than four inquiries between 2004 and 2010 by the Business, Innovation and Skills Select Committee (also under its various guises of the ‘Trade and Industry Select Committee’ and the ‘Business and Enterprise Select Committee’).

The Committee made a series of increasingly robust calls for reform in the sector. These focused chiefly on the recommendation that the Government should consider how best to secure a ‘free of tie’ opportunity for tied tenants.Footnote 55 The solution adopted until 2013 was to push the industry to self-regulate, with the Government noting that: ‘legally binding self-regulation can be introduced far more quickly than a statutory solution and can, if devised correctly, be equally effective’.Footnote 56 However, in light of the same problems persisting, patience soon ran out. As the Business, Innovation and Skills Select Committee warned in 2010:

The industry must be aware that this is the last opportunity for self-regulated reform. If it cannot deliver this time, then Government intervention will be necessary.Footnote 57

By 2013, the Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, Vince Cable, had concluded that regulation was necessary. He consulted on the establishment of a statutory code presided over by an Adjudicator who possessed regulatory powers, based on the same model as the recently formed ‘Groceries Code Adjudicator’.Footnote 58 It is in the context of this long, sustained regulatory scrutiny of the tied pub model that the mechanisms within the next section should be understood.

2. Mechanisms in the Pubs Code Regulations 2016

The raison d'etre of the underpinning Pubs Code is founded in two animating principles specified in Part IV of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015. The design of the underpinning Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016 stems from s 42(3), which requires that the Code (ie Parts 2–10 of the Regulations) and the function of the PCA are consistent with:

(a) the principle of fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants;

(b) the principle that tied pub tenants should not be worse off than they would be if they were not subject to any product or service tie.

These two principles are returned to frequently in both the Pubs Code itself and in decisions by the adjudicator in arbitrations. As the PCA puts it in Edward Anderson v Marstons plc:Footnote 59

All of the issues in the case should be considered in the light of the overriding principles found in section 42 of the 2015 Act because they are the starting point to understanding the Pubs Code and the statute that enabled it… The core Code principles are at the heart of the statutory purpose behind the establishment of the Pubs Code regime…

The Pubs Code is enacted under these principles, taking shape through The Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016 and The Pubs Code (Fees, Costs and Financial Penalties) Regulations 2016. These regulations apply to pub-owning companies with more than 500 pubs in their estate – currently six PubCos and at least 11,500 tied pub tenants in total.Footnote 60 As far as the adjudicator's dispute settlement role is concerned, the regime is a creature of statutory arbitration and falls under the framework outlined in s 94 of the Arbitration Act 1996. There are two key mechanisms for tenants in the Code – those to break free of tie and those handling the review of rent – which are accompanied by the PCA's regulatory function. Each is dealt with in turn.

(a) Breaking free of the tie: the market-rent only escape

The so-called ‘market rent only’ (MRO) offer is the flagship intervention in the Pubs Code, designed to underpin the Pubs Code principles.Footnote 61 It provides a statutory right to break free of a tied arrangement and simply pay a market rent for the property, without the obligations of the ‘wet rent’ in the form of stocking requirements and arrangements of exclusive supply. By providing this final back-stop, the principle is that tied tenants can better negotiate their current tied agreements and – should they be dissatisfied with their negotiated tied lease – break free from it altogether.

In practice, the arrangements are complex and have been marred by problems with dispute resolution practices that we return to below. The ‘MRO offer’ process is only ‘triggered’ in a set of finite circumstances, such as the renewal of a lease or a rent assessment,Footnote 62 at which point, the PubCo must provide a compliant ‘MRO offer’ to the tied tenant. This must be a lease that ‘does not contain any product or service tie’ (with the exception of insurance arrangements), and ‘does not contain any unreasonable terms or conditions’.Footnote 63 The only other requirements are detailed in regulations 30 and 31 of the Pubs Code, which specify terms that are required in the proposed tenancy (eg that it is for a period at least as long as the remaining term of the existing tenancy), and when terms would be considered unreasonable (eg that they are terms which are which are not common terms in agreements between landlords and pub tenants who are not subject to product or service ties).

What emerges, therefore, is a mechanism for tied tenants to receive an ‘MRO’ lease – notionally designed to mirror free-of-tie leases – in response to certain trigger events, with a wide discretion afforded to both the PubCo and the PCA in determining the compliance of such offers. The only organising concept that the Pubs Code supplies is that of ‘reasonableness’: both in broad terms within s 43(4) of the 2015 Act, and in determining those ‘terms which are not common terms in agreements between landlords and pub tenants who are not subject to product or service ties’ under reg 31(2)(c) of the Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016.

(b) David and Goliath: information asymmetry and rent reviews

Although the MRO process provides (at least in principle) the option to break away from tied arrangements for tenants, to help ensure the principle of ‘fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants’ who remain in tied leases, the Pubs Code creates a series of processes for the review of rent. These are, as the PCA itself noted, a fundamental part of giving effect to the regulations’ ‘overriding principles’.Footnote 64

The ‘rent assessment’ processes under the Pubs Code are effectively process-based duties to disclose information in a rent negotiation.Footnote 65 They are much in the spirit of addressing ‘asymmetries of information’ market failures that can characterise contractual arrangements between parties with inherently imbalanced powers and access to expertise.Footnote 66 In their nature as large-scale property owning businesses, PubCos are well-versed in thousands of rental negotiations and will have access to specialist in-house advice and the resources to secure outside consultancy. In comparison, the tied tenant has far fewer resources and is likely to have little or no experience negotiating rent for other leases; this is especially true for relatively new entrants into the sector.

Fundamentally, the regulations require that any rent assessment be completed in accordance with Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors’ guidance and accompanied by written confirmation from a chartered surveyor to confirm this.Footnote 67 The relevant guidance details, in broad terms, the process of calculating the fair maintainable operating turnover and profit that defines the approach to determining tied pub ‘dry rent’ detailed above.Footnote 68

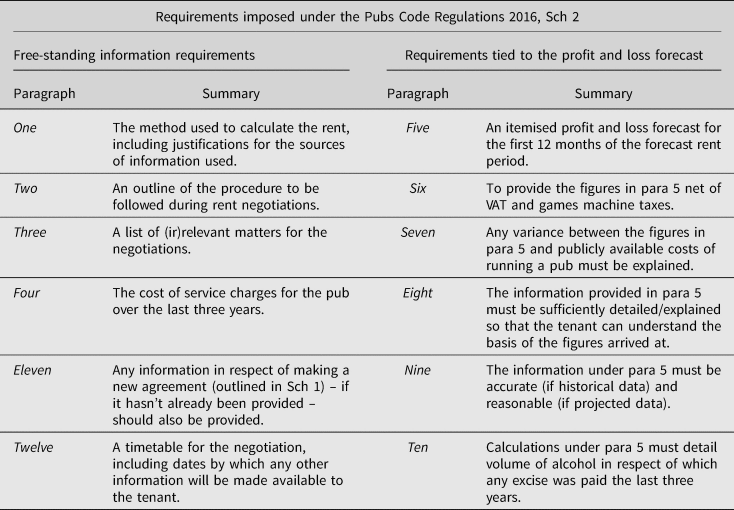

Over-and-above this requirement, however, the information-sharing requirements on the PubCo are extensive. Laid out in Schedule 2 to the 2016 Regulations, they detail the provision of key information to inform negotiations over rent – such as the PubCo disclosing the method used to calculate the rental offer and providing a fully itemised profit/loss account. Table 1 provides a summary of these: paragraphs five to ten of the schedule all introduce requirements for the profit/loss forecast, and the remaining paragraphs introduce other free-standing requirements to disclose information (eg providing a list of relevant and irrelevant matters for the negotiations).

Table 1. A summary of the specified information detailed in the Pubs Code Regulations 2016, Sch 2

This focus on the provision of information and transparency of the negotiations is found elsewhere in the Code. Most notably, for all meetings between the PubCo and the tied tenant, an appointed business development manager or representative of the PubCo must make ‘appropriate notes of any discussions’ with the tied tenant in relation to negotiations under the Code, including for rent proposals and assessments, and provide these to the tied tenant within 14 days.Footnote 69 Indeed, Marston plc's failure to provide complete notes of discussions with a tenant (and providing these nine days late) has been the subject of a PCA arbitration decision against them.Footnote 70

In the course of arbitrations and written guidance from the PCA, these wide-ranging information disclosure requirements have been interpreted in line with the ‘fair and lawful dealing’Footnote 71 principle at the heart of the Pubs Code. This has added two layers of gloss to Schedule 2. First, PubCos must disclose the listed documents in a way that is accessible to a tied tenant. As the PCA puts it in one such arbitration:

Consistency with the principle of fair and lawful dealing between a POB and a [tied pub tenant] in my view requires that obligations be complied with in a transparent and accessible manner, that enables a TPT to access their rights under the Code.Footnote 72

It is not enough, therefore, that a PubCo provides the list of information detailed in the schedule: it must also be ‘easily accessible and understood by tenants’.Footnote 73 Secondly, PubCos have a wide-ranging duty to comply with any ‘reasonable request’ by the tied tenant to disclose further information under regulation 21(3), or to provide a ‘reasonable explanation’ as to why the information requested cannot be provided. It is clear from a series of arbitrations that such a request being ‘time-consuming’ and requiring a substantial ‘financial outlay’, are not sufficient reason to refuse an otherwise reasonable request.Footnote 74

(c) Referrals to arbitration and appeals

The basic principle is that any failure by a PubCo to comply with arbitrable provisions of the Pubs Code dealing with either of these mechanisms can be referred by the tied tenant to the PCA for abritration.Footnote 75 In common with some other forms of business-to-business dispute resolution (such as with banks),Footnote 76 the larger party has more limited rights to refer. Under the Pubs Code, a PubCo can only refer disputes in relation to the MRO process;Footnote 77 all other disputes can only be referred by the tied tenant. PubCos cannot navigate out of the PCA's involvement in an MRO dispute if the lease agreement between the two parties already contains an arbitration clause – in such cases, the tied tenant can appoint the PCA as the arbitrator.Footnote 78

Whether arbitrated by the PCA itself (as was common within the first few years of the Code's operation), or by another arbitrator it appoints,Footnote 79 this is a ‘statutory arbitration’ regulated under s 94 of the Arbitration Act 1996. This allows for some limited appeal rights to the High Court where the arbitration suffers from a serious irregularity (for instance, the arbtirator failed to deal with all issues put to it, or the award is ambigious),Footnote 80 or on a point of law (for instance, the arbitrator misinterpreted the provisions of the Pubs Code Regulations 2016).Footnote 81 Both have been grounds for a series of appeals, discussed below.Footnote 82

3. Regulatory powers in the code adjudicator model

The other side of the PCA's Janus-face is its regulatory responsibility. This is a broad-ranging set of investigatory and enforcement powers conferred by the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015.Footnote 83 Wherever the PCA has ‘reasonable grounds’ to suspect that a PubCo has not complied with the Code, it can trigger a wide-ranging investigative power, including the ability to enforce the disclosure of documents from a PubCo.Footnote 84 For PubCos found to have breached the code, the PCA has the power to issue considerable fines of up to 1% of the PubCo's turnover, make binding recommendations for improvements, or require the publication of information.Footnote 85 For the largest PubCos – such as EiGroup, with a turnover in 2018/19 of £724 millionFootnote 86 – the potential fines are considerable. Guidance issued by the PCA refers broadly to adopting the ‘Macroy principles’ in the assessment of any such penalty: broadly, using sanctions proportionally to change the behaviour of the offender and deter future non-compliance.Footnote 87

At the time of writing, there has been one such investigation triggered by the PCA. This launched three years after the introduction of the Pubs Code in July 2019 and focused on the routine adoption of non-compliant stocking requirements by Star Pubs & Bars Ltd. Following a lengthy investigation process, the PCA triggered a notice to Star on 14 October 2020 under s 58(2) of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 to impose a financial penalty of £2 million, noting in the investigation that:

Star must change its mind set, to be proactive in its approach to compliance. This can best be achieved through the imposition of a sanction that will serve as a deterrent to future non-compliant conduct by Star and other POBs.Footnote 88

Notwithstanding this significant investigation and resulting fine against Star Pubs & Bars, the PCA has recognised that its regulatory function has been neglected in the first few years of the Pubs Code's operation, in favour of a focus on arbitration functions. This is, in part, a function of the PCA's Janus-face – arbitration decisions were used routinely for clarifying aspects of the code. In its response to the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy's review, the PCA itself noted how its ‘dual statutory functions have frequently exerted pressures on each other’.Footnote 89 It has signalled its intention to ‘mov[e] decisively’ away from managing individual arbitrations, and instead to focus on ‘regulatory interventions to increase the pace of behavioural and cultural change and to embed compliance’.Footnote 90 The PCA's regulatory role has also suffered from a lack of clarity on the meaning of some aspects of the underpinning Pubs Code regulations. Indeed, as the PCA itself notes in response to the statutory review, ‘it is highly unusual for the regulator to have to make decisions on what the law means ahead of taking regulatory action on that law’.Footnote 91

Similar tensions arise when information gained through the PCA's regulatory function bites on ongoing arbitrations. This was the issue before the court in Highwayman.Footnote 92 Here, a document attained from Star Pubs and Bars Ltd in the course of the PCA's regulatory work – a 10-year lease policy on MRO responses – was forwarded by the PCA to a tied tenant engaged in an ongoing arbitration with the company. Star Pubs and Bars Ltd objected to the document disclosed in the PCA's regulatory function being forwarded without their permission to a tied tenant engaged in its arbitration function.Footnote 93 Although the case turned on other issues,Footnote 94 the court noted that this dual function was built into the Code Adjudicator model. The ‘regulatory and arbitration functions’ of the PCA cannot be ‘chopped apart’.Footnote 95

4. Problems with the Pubs Code adjudicator model

As outlined at the start of this paper, Hodges argues there are two core objectives for any new model of dispute resolution: to identify problems and resolve them, and to change future behaviour or systems based on problems its users encounter. Footnote 96 Having established the problems that the PCA and the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 seek to address and the mechanisms intended to resolve them, this section turns to whether the introduction of this new intermediary has achieved its aims, and whether there is evidence of more systematic change.

The analysis below deals with four issues that emerged in our research: (i) delays and cycles of arbitration; (ii) the small number of MRO leases agreed; (iii) the burden of proof; and (iv) interaction with the tied tenants’ prior legal relationship with the PubCo. In the course of this analysis we draw on interview and arbitration data. The former is based on 14 anonymous semi-structured interviews with tenants who have engaged with the MRO procedure. Participants were recruited via stakeholders who provide advice on the exercise of Pubs Code rights in the pub sector – each interview was conducted via Zoom during May and June 2021, and the audio subsequently transcribed and analysed. The study received ethical permission from the University of York Economics, Law, Management, Sociology and Politics Ethics Committee. The arbitration data is based on a sample of 43 PCA arbitration decisions published on the PCA Government website and four appeals under s 68 and s 69 of the Arbitration Act 1996.Footnote 97 These cover both the MRO and rent assessment mechanisms above.

(a) Delays and cycles of arbitration

As Hodges argues, the time taken to resolve a dispute is ‘an important key performance indicator’ of any dispute resolution model.Footnote 98 This is especially true in instances where there are inherent resource imbalances between the involved parties. Here, protracted processes and delays can disproportionately deplete the resources of the smaller party, which in turn provides an incentive for the larger party to game the system. The literature on international arbitration points to delay as a ‘guerrilla tactic’ in arbitration proceedings – particularly in the context of case management processesFootnote 99 – and the importance of ensuring that control of arbitration processes are not ‘skewed in favour of one party’.Footnote 100

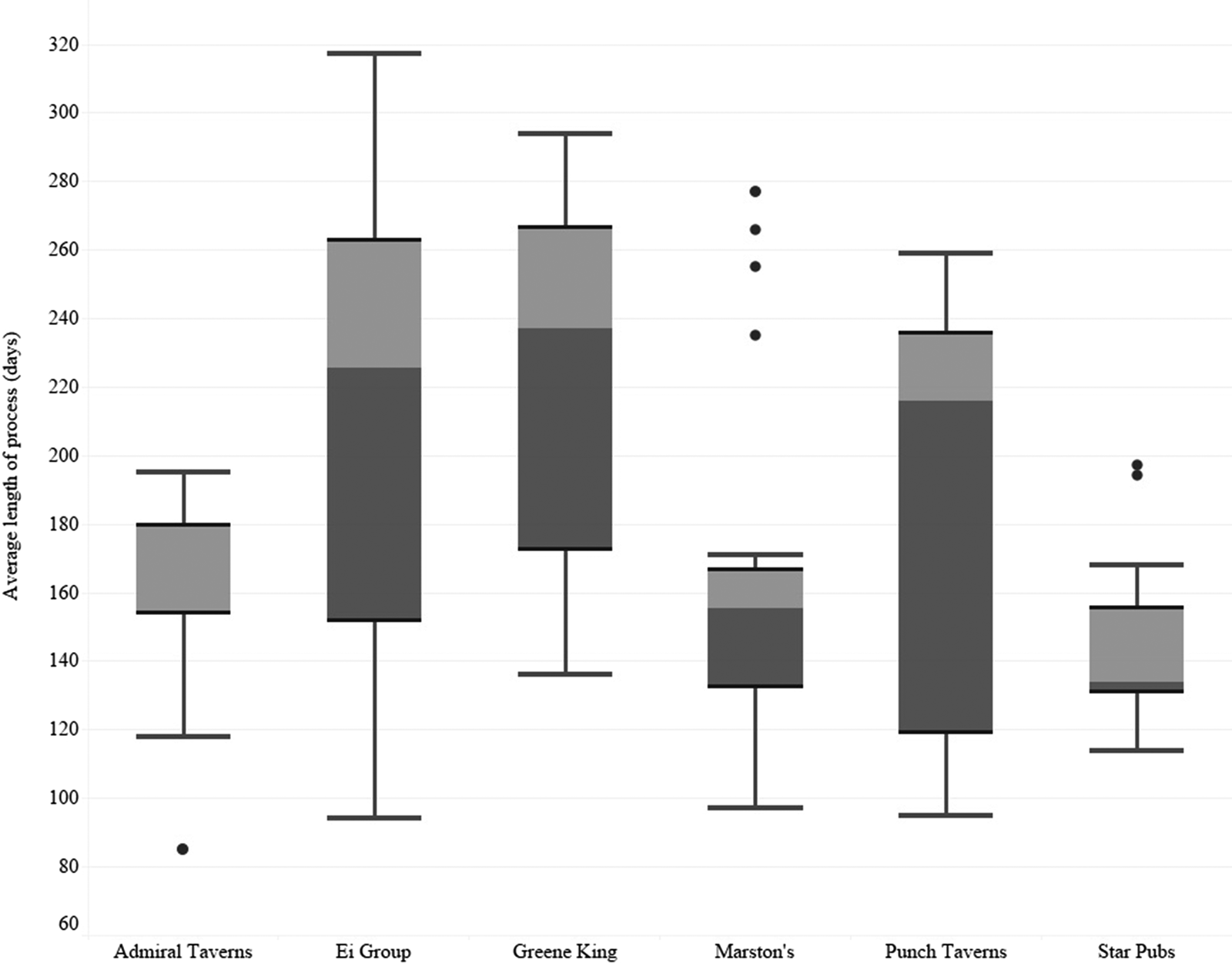

The tactical use of delay is a particularly acute problem for the Pubs Code. Its raison d'etre is to address the considerable power and resource imbalances between unequal parties, as reflected in one of its underpinning statutory aims to ensure ‘fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants’.Footnote 102 The use of delay to deplete resources or make the arbitration less appealing could in turn render Code rights entirely illusory. However, contributors to the Government's statutory review of the Pubs Code pointed to problems with the length of the process between triggering an MRO right and a negotiated outcome, leading both to the costs associated with arbitration and the ‘delay in seeing the benefits of a new tied agreement or MRO’.Footnote 103 Data on MRO processes in Figure 2 show that there are considerable variations between PubCos, with a median of 164 days from triggering the process to an outcome. However, particularly for Ei Group and Greene King, it is not usual for this period to be far longer, with median timescales of 226 and 237 days respectively.

Figure 2. A box-plot illustrating the average delay average delay between MRO applications and outcomes between 1 July 2017 and 1 January 2020Footnote 101

There are structural factors within the Pubs Code which may exacerbate these delays, principally the power of an arbitrator to direct the inclusion of specific terms within an MRO lease. This was the focus of a referral to the High Court under s 69 of the Arbitration Act 1996 in Punch Partnerships v Highwayman Hotel,Footnote 104 in which the court considered whether an arbitrator could direct a particular term – in this case, a specific lease length – into an MRO offer in order to avoid protracted litigation between the parties. At the initial arbitration, the PubCo had argued that the power of the arbitrator (in this case, the PCA itself) under regulation 33(2) of the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 only allowed it to direct a revised MRO response, not to specify what terms should be included in such a response. In the original arbitration, the PCA noted that:

[The PubCo's] interpretation of my powers under regulation 33(2) is such as to provide the potential for locking a tied pub tenant into a cycle of litigation. Such delay would place a greater burden on the tenant than on [the PubCo] as a huge international brand with deep pockets.Footnote 105

This danger of the revolving door of arbitration was noted by the High Court, which accepted that such an interpretation of the arbitrator's powers poses ‘a risk of further delay, cost and attrition involved in repeated offers and arbitration’ that ‘might harm the Tenant more than the [PubCo]’.Footnote 106 However, although the Pubs Code provides the PCA with the power to require a PubCo to issue a revised response, it could not determine the terms within that response: that is to be left to the PubCo, and then subject – if needed – to further arbitration. The permissive language in regulation 33 was not enough to ‘empower the arbitrator to interfere with the economic and property interests of the parties’; for the court to be satisfied that such a power exists, it needed to be more clearly expressed in the underpinning legislation.Footnote 107

The problem of delay was raised routinely by participants in our sample – always negatively. A majority considered that delay was used as part of a PubCo's efforts to make the process more difficult for tied tenants and/or to encourage them to remain tied. As one participant put it:

It gets to the point that with every communication they stretch it to the limit of when they have to reply, so if you add all of them communications up – even when you ring them, it's ‘oh, I'll get back to you’… the delaying tactics are just prevalent throughout.Footnote 108

This is particularly acute for the majority of tied tenants opting for legal representation, given the complexities of the code and of commercial leasehold law more generally. Especially for operators with multiple sites, delays can quickly lead to very expensive legal fees:

I didn't achieve MRO on any of my sites – not one – my legal fees came to over £100,000, which just makes me shudder at the thought of it now. And I lost all of my pubs… with them being taken back into managed houses.Footnote 109

These additional costs are not limited to engagement with the MRO process (such as of representation) and of uncertainty, but also because new free-of-tie arrangements are not back-dated under the legislation. If there is a delay to reaching a free-of-tie agreement, rent differentials are not back-dated to the point of the MRO trigger. As one participant put it:

Nothing is back-dated, so every time anything is slowed down by the PubCo or the PCA – both of which were very good at that – then I lost out financially, and every time I stuck to a principle I knew it would take years and cost me loads of money. So all the incentive is there just to continue tied.Footnote 110

Both the arbitration and interview data therefore illustrate that delay – and the possible use of delaying tactics – were a particularly acute issue in the first years of the Pubs Code's operation.

(b) Arbitration outcomes

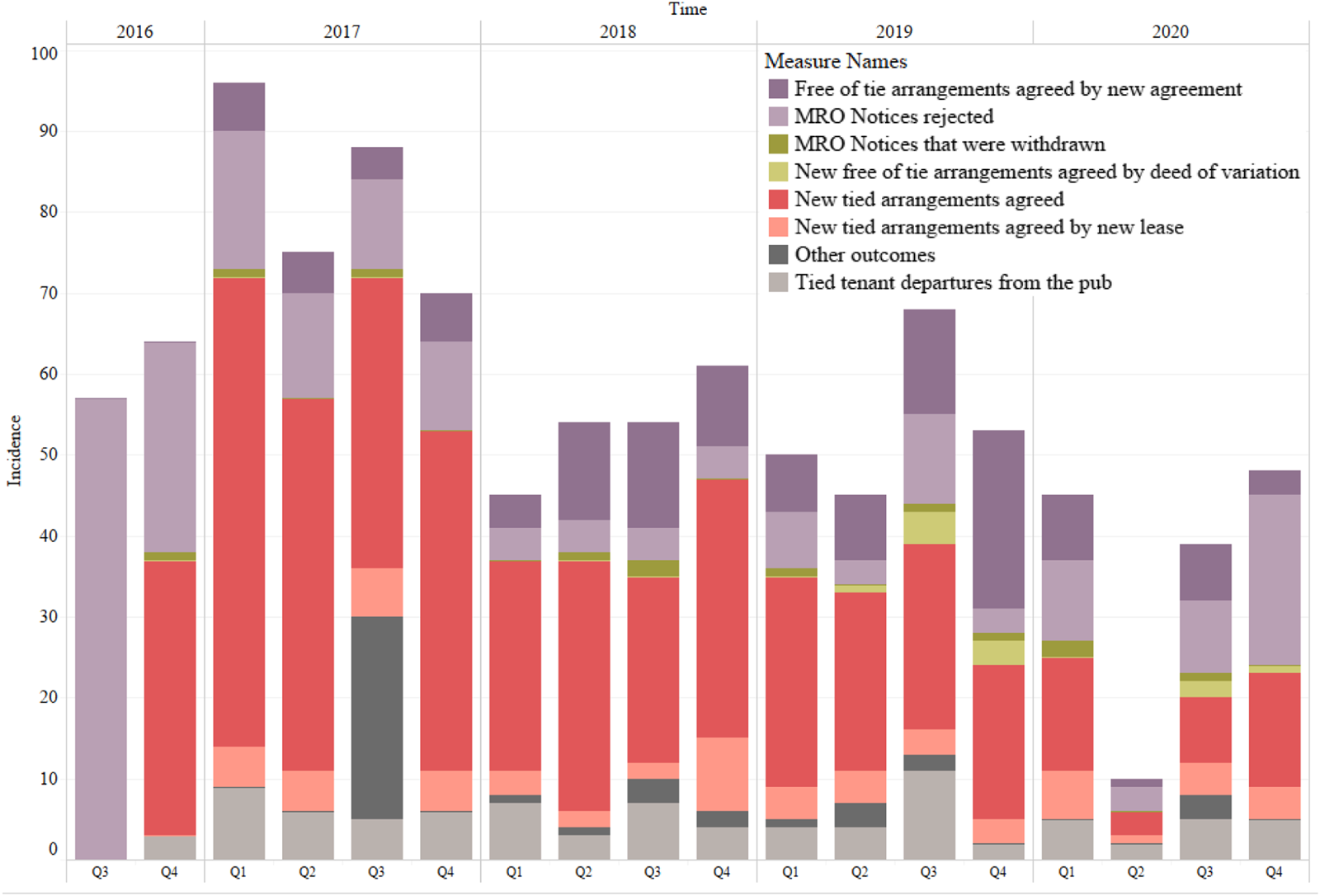

The delays between MRO application and outcome outlined at (a) above should be read alongside the data on arbitration outcomes – what do parties agree at the end of the statutory arbitration process? Figure 3 details the outcomes that follow the triggering of the MRO mechanism, broken down by year and quarter. These data show that, notwithstanding that the MRO option is the Pubs Code's flagship intervention, these free-of-tie arrangements are relatively rare. Nearly half the outcomes are tenants entering into new tied arrangements with the PubCo (457 by variation to their current lease or 66 via a new lease), whereas free-of-tie arrangements accounted for 129 outcomes over the same period – significantly lower, even, than the number of MRO notices rejected (218 in total). The Pubs Code can hardly be described, therefore, as a wholesale transfer of tied leases to free-of-tie leases.

Figure 3. Outcomes following an MRO request from the introduction of the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 to the end of 2020Footnote 111

There are two ways of interpreting these data. First, they may illustrate that the Code itself is working. By exerting an effect on negotiations between tied parties, even if they may not conclude with tenants exercising their statutory right to a free-of-tie arrangement, the MRO process may in turn be improving the state of tied leases. Put another way, the potential for going free-of-tie leads the PubCo to improve the terms of existing tied leases, for instance by including more options to buy outside of the tie, particularly for cask beer. However, it may also illustrate limitations within the regulations. For instance, the tight 14-day referral windows within the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 may in turn be insufficient to support adequate negotiations between the parties.Footnote 112 Within our interview data, the tied referral windows did emerge as a key barrier for tenants seeking PCA arbitration involvement. This was particularly in the context of concerns over missing key dates laid out within the legislation:

One of the things that started scaring me was that there were what seem to be very restrictive timelines, during which you must complete certain factors, certain parts of it, which I personally feel are not highlighted enough, and not brought to your attention, like ‘you must do this’.Footnote 113

The MRO data therefore suggest that reforms to referral windows for tied tenants looking to dispute an MRO offer – laid out within regulations 37 and 38 of the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 – would likely support tied tenants in their negotiations with a PubCo following an MRO trigger; especially for those without the resources for full legal representation.

As our research took place in the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is clear that differential support offered to tied tenants and under free-of-tie leases was also an important factor for participants. One participant had received an MRO offer that they were keen to accept. However, they were concerned that the PubCo would not offer any rent discounts or support while the pub was closed – something they had done for tied tenants. As the participant put it:

I just couldn't afford taking the risk with Covid-19… I thought, what if I say yes? What if I sign this tomorrow? I'd be paying £100,000 a year rent, with no income. I can't do that. There's only so many £2,000 a week I've got. So I couldn't have done it, I couldn't have risked it during Covid.Footnote 114

Although at the time of writing available MRO data only runs to the end of 2020, this may explain why Figure 2 illustrates that free-of-tie arrangements are even lower as a proportion of outcomes than from before the pandemic. Indeed, representations from Star Pubs and Bars Ltd in the passing of the Tied Pubs (Scotland) BillFootnote 115 underscore that rent reductions ‘show the true partnership nature’ of the tied model, whereas similar provision is not provided for free-of-tie tenants.Footnote 116

(c) Burden of proof

Ordinarily in arbitration, the burden of proof for a given allegation rests on the party asserting it. Known variously as the ‘actori incumbit probatio’ principle (the ‘actor's burden of proof’) or ‘onus probandi actori incumbit’ principle (‘the burden of proof lies on the petitioner’), this is the ‘general trend’ in arbitrations and the default starting point for burden of proof disputes that arise in arbitration proceedings.Footnote 117 The burden of proof is a fundamental component in arbitration disputes for two reasons. First, it provides a framework for each party's conduct. As Amaral puts it, the burden of proof ‘works as a vector for the parties’ action concerning the production of evidence’.Footnote 118 The extent of obligations to produce evidence in turn affects what parties can claim and dispute in the course of arbitration proceedings. Secondly, it provides a means for the arbitrator to take a decision in absence of evidence, or as Amaral describes it, the burden of proof ‘offers a way out whenever relevant evidence is missing’.Footnote 119

However, in the UK, the operation of the burden of proof standard is far from fixed to this default standard. The Arbitration Act 1996 confers wide-ranging powers for an arbitrator to ‘rule their own evidence’, subject only to appeal based on a serious irregularity.Footnote 120 Where there is a ‘marked asymmetric relationship’ between the parties affecting the ‘the equality of arms’, a different approach may be justified.Footnote 121 This is particularly true in instances where the burden of proof for one party cannot be discharged without evidence that only the opposing party has access to, or the resources to attain.Footnote 122

The burden of proof is a key concern in the discharge of arbitration functions by the PCA, particularly in terms of the MRO mechanism outlined above. Where does the burden of proof lie in determining whether an MRO-offer is compliant with the Pubs Code: with the PubCo making the offer, or the tied tenant contesting its validity? This question was considered by the High Court in Jonalt. Here, the PubCo had proposed a ‘stocking requirement’Footnote 123 in their MRO offer requiring the tied tenant to stock ‘at least 60%’ of their brands, here Heineken products. The tied tenant argued that this stocking requirement was unreasonable and counter-offered a 20% threshold. The arbitrator considered that the onus was on the PubCo to demonstrate that their offer was reasonable and – as they had failed to do so – directed the inclusion of the 20% threshold in the MRO lease offer.

On appeal, the High Court determined that ‘on the normal rules of the burden of proof, the onus lay on the tenant to establish the breach alleged’,Footnote 124 and there was nothing in the Pubs Code to infer otherwise.Footnote 125 Reversing this standard without inviting submissions from the PubCo was a ‘serious irregularity’ by the arbitrator under s 68 of the Arbitration Act 1996.Footnote 126 This is a significant departure from the position of the PCA in a series of arbitrations under the Pubs Code and seems contrary to the construction of the MRO mechanism. The entire animating principle of the MRO offer process is to require a PubCo to issue a ‘compliant’ offer to the tied tenant under s 43(4)(a) of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015. Where such an obligation rests on one party, it is difficult to see how the burden of proof rests on the other. As the PCA puts it in one arbitration:

[The PubCo] argued that the burden of proof to show a proposal was not compliant lay on the tenant who brings the referral for arbitration. However, in the context of this legislation, it is the statutory duty of the POB to service a proposal that is compliant, and I understand it therefore to be the obligation of the POB to consider what would be compliant in the particular case when serving its proposal.Footnote 127

This burden of proof problem is a fundamental issue when designing statutory arbitration systems intended to deal with two parties with such inherent power imbalances. If, as Amaral argues, the burden of proof standard in arbitration proceedings serves to frame the conduct of the parties,Footnote 128 it is surely in the interests of the PCA and most consistent with its underpinning statutory aims to ensure that the burden of proof for MRO-compliant offers lies with the PubCo. An obligation to provide evidence to substantiate this would, in turn, be likely to increase the quality of these offers and decrease the costs and risks associated with arbitration for tied tenants.

(d) Interaction with prior legal relationship

Policymakers and affected PubCos have referred consistently in both the development and ongoing operation of the Pubs Code to potential problems of ‘unintended consequences’. Indeed, the phrase is mentioned on no fewer than five separate occasions within the 2019 statutory review.Footnote 129 The concerns are perhaps best reflected by the British Beer and Pub Association (a trade body representing a number of PubCos) post-legislative review submission.Footnote 130 This highlights a particular concern that the introduction of MRO rights may lead to the ‘unintended consequences’ that PubCos begin to convert the tied tenanted pubs, which can avail themselves of Pubs Code rights, into owner-managed pubs, where the PubCo simply appoints a salaried manager for the premises and vertical integration is maintained.Footnote 131

The literature on statutory arbitration has long raised concerns over the interaction between new interventions and pre-existing legal arrangements. This critique normally tackles interactions between statutory arbitration and common law doctrine,Footnote 132 or – as recently argued by Oppong – possible conflicts between statutory arbitration and protections afforded to public parties under constitutional law.Footnote 133 As a statutory intervention concerned with the rights of tied tenants, the Pubs Code inevitably has consequences for the legal relationship between landlord and commercial tenant. In most cases, tied tenants benefit from the application of protections in the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 which, inter alia, limit the reasons for which a landlord can refuse the renewal of a lease.Footnote 134 The MRO rights under the Pubs Code are exercised as a distinct process, not as part of lease renewals governed by the 1954 Act: the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 were amended following the introduction of the Pubs Code to allow the court to delay any renewal proceedings pending the outcome of the MRO process.Footnote 135

However, important blind spots emerge in the interaction between these two processes. As outlined above, one MRO trigger is the renewal of a tenancy – either following notice from a PubCo,Footnote 136 or a request by the tied tenant.Footnote 137 In response, PubCos can issue hostile notices to refuse renewal on the basis that they intend to ‘occupy the holding for the purposes… of a business to be carried on by him therein’.Footnote 138 Such notices allow PubCos to instead transfer properties into their managed estate, appointing a salaried management rather than a tenant landlord. This is not without cost to the PubCo. Opposing renewal on this ground will require the payment of compensation – perhaps as much as two times the ratable value of the property – and can be contested by the tied tenant by, for instance, interrogating the validity of the business plan for such an owner-managed approach.Footnote 139 However, this widespread practice illustrates that the Code's protection can be circumvented via a re-existing and largely unreformed legal relationship within the parties.

Conclusion

The PCA and the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 are historic interventions in the much-maligned tied pub sector. They follow a catalogue of failed regulatory attempts to deal with anti-completive practices in the pub sector in the UK stretching back to least the early nineteenth century. In adopting the ‘code adjudicator’ model, this new intervention seeks to intervene in the contractual relationship between the largest PubCos and their tied tenants. By improving their negotiating power and offering an exit route from the tie through access to an MRO tenancy, the quality of tied agreements may in turn improve and – should tenants be dissatisfied with current arrangements – they can break free. However, the model also attempts to underpin standards set out in the Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016 through its regulatory mechanisms, enforcing the twin principles of ‘fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants’ and ‘that tied pub tenants should not be worse off than they would be if they were not subject to any product or service tie’ that are the raison d'etre of the PCA laid out under its enabling legislation.Footnote 140

Drawing on arbitration decisions and appeals, interviews with affected tenants and data on MRO outcomes, we have argued that the current operation of the PCA and the Pubs Code Regulations 2016 falls short of these aims. Some of the problems that emerge are specific to the PCA. Delaying tactics, the lack of realisation of MRO rights and concerns raised about referral windows, suggests that more should be done to reform the arbitration processes and underpinning regulations of the PCA. However, other concerns have broader purchase on the ‘code adjudicator’ model. As an intervention into a prior contractual relationship, careful consideration should be given to the potential for interactions with pre-existing legal rights that could undermine the operation of the Code. Moreover, the ‘burden of proof’ standard ordinarily applied to arbitration proceedings may not suit aspects of ‘code adjudicator’ models that place specific burdens on the larger parties within the underpinning statutory code.

Returning to Hodge's characterisation of the two core objectives for any new model of dispute resolution – to identify problems and resolve them, and to change future behaviour or systems based on problems its users encounterFootnote 141 – our findings suggest that the current operation of the PCA currently falls short on both measures. However, notwithstanding these limitations, the ‘code adjudicator’ model has exerted a positive effect on the market and shows promise as a form of regulatory intervention. The new Tied Pubs (Scotland) Act 2021 – passed unanimously by the Scottish Parliament on 5 May 2021 – introduces a parallel system in Scotland, but one which seeks to ‘avoid problems experienced in implementing the 2015 Act in England and Wales’.Footnote 142 As the underpinning powers, Code and operation of Scottish Pubs Code Adjudicator are fleshed out in secondary legislation, comparing their success against their English and Welsh counterpart will provide fertile ground not only to explore the functioning of the Pubs Code Regulations 2016, but also that of the ‘code adjudicator’ model itself.