In 1921, the Territory of Alaska enacted a “license tax on the business of fur-farming, trapping and trading in pelts and skins of fur-bearing animals.”Footnote 1 The “fur tax” was a two-tiered legal instrument. Specifically, fur-farmers and fur-buyers alike were required to “secure” an annual license.Footnote 2 In addition, each pelt they would “take” or “purchase” would then trigger payment of another fee—ranging from as low as $0.05 for muskrats and weasels to $10 for moose trophies and even skyrocketing to $100 for sea otters.Footnote 3 Trappers, however, were normally exempted and only had to pay the latter fee when they chose to sell their pelts to non-licensed fur-buyers.Footnote 4

Alaska Attorney General John Rustgard confirmed the primary purpose of the fur tax on 17 August 1921, while responding to Game Warden Edward A. Young’s inquiries about its scope and implementation. The tax, Rustgard explained, “is strictly a revenue measure.”Footnote 5 At the time, one could very well understand why it was so. Furs had generated about $90 million (Cole Reference Cole2004: 17) since the “1867 Alaska Purchase” (see Huhndorf and Huhndorf Reference Huhndorf and Huhndorf2011: 389), and in 1918 alone, more than $2 million worth of the commodity left the U.S. territory.Footnote 6 Though negligible compared to amounts contributed by fish and minerals—the two Alaskan economic pillars—it still made sense for territorial officials to try and tap into this economic (and fiscally appealing) resource.Footnote 7 Besides, Rustgard remarked, the tax “should be enforced with the view of creating as little friction as possible. It is one of the laws adopted as a necessity for the purpose of escaping the creation of a machinery with which to levy a direct tax on real and personal property.”Footnote 8 In responding to Young, the attorney general thus strived to underscore the revenue-raising nature of the tax and its ability to minimize popular discontent.

Although Rustgard added that the fur tax “applies equally to natives and to white people,”Footnote 9 the former, who had lived on the land since time immemorial and for whom subsistence was their “way of life” (Berger Reference Berger1985: 48–72), were logically better prepared to become trappers.Footnote 10 In fact, the fur business had swiftly evolved to reflect this reality. “By the very nature of the business, character of country, and climate of Alaska,” painter Henry Wood Elliott reported in Reference Elliott1875, “White men will never themselves do any sea-otter or other mainland trapping; it rests solely with the natives, and the annual yield depends entirely upon the exertions which these people may be inclined to make as a means of procuring coveted articles in the hands of the traders” (Reference Elliott1875: 41).Footnote 11 Hence, the broadened scope of the tax would likely cause severe economic harm to Native trappers,Footnote 12 who in 1921 still dominated the industry.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, and mere fiscal pressure aside, could other, more damaging effects have existed?

This article proposes to push back against Rustgard’s contention that the tax was just a means to raise revenue. Indeed, it was part of a broader settler colonial agenda that intensified in 1912 when Alaska became a U.S. territory.Footnote 14 Federal and territorial officials, teachers, missionaries, and other key stakeholders sought to assimilate Alaska Natives, mainly through schooling and religion (Getches Reference Getches1977; Zahnd Reference Zahnd2022; Dinero Reference Dinero2016; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003; Haycox Reference Haycox2002). Their common goal was to manufacture “civilized”Footnote 15 subalterns that could eventually join mainstream society as second-class citizens—legally, socioculturally, and economically (e.g., Schwaiger Reference Schwaiger2011; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003).Footnote 16 Within this ecology of colonial techniques, the fur tax was most entangled with the successive 1902 and 1908 game laws that sought to monitor and control hunting practices. But the tax also belonged to a much more ambitious plan. Indeed, the young polity and the federal government wished to teach semi-nomadicFootnote 17 Native hunters how to become spatially grounded capitalist gardeners, reindeer herders, or wage workers.Footnote 18 “[H]unting and gathering,” Bathsheba Demuth points out, “had to give way to an agricultural or industrial existence if Alaska were to be American” (Reference Demuth2019b: 147).

The goal, then, was to “civilize” hunter-gatherers.Footnote 19 To be sure, there was little, if any, attempt to conceal this assimilationist endeavor. As Alaska became U.S. land, it was already widely understood that, “If uncorrupted by ardent spirits, not outraged by ill usage, nor confounded by those sources of Indian wars which we call treaties, of which this government has negotiated between 400 or 500 with the tribes within its limits, the natives of Alaska will become civilized, prosperous, and useful in agriculture, commerce, and the fisheries.”Footnote 20 In a similar vein, Matthew Hannah (Reference Hannah1993) has demonstrated how the U.S. government deployed an analogous policy toward the Oglala Lakota, enforcing “spatial fixation” to facilitate assimilation (mainly through agriculture) and using Foucauldian “disciplinary” powers (see also Biolsi Reference Biolsi1992; Reference Biolsi1995).Footnote 21 The seemingly neutral nature of the tax fades away once one takes a closer look at hunting, agrarian, and pastoral policies. Therefore, repositioning the fur tax within a larger frame of inquiry and analysis makes it easier to look at official discourse—such as Rustgard’s foregoing contentions—anew.

What follows is a sociolegal vignette of Alaska’s settler colonial history. Specifically, I interrogate how the Territory of Alaska—alongside the federal government—deployed several forms of power, including the fur tax, to manufacture Native subjects to its liking. What makes Alaska an ideal case study is that ice, undoubtedly one of its best-known characteristics, constitutes the natural nemesis of colonization. Ice, Jen Rose Smith posits, simultaneously impeded agricultural practices (and, in the process, settlement) and exacerbated the racialization of Alaska Natives, who were de facto prone to mobility—a process she calls “temperate-normativity” (Reference Smith2021). By and large, Alaska’s geography, climate, sheer size, and remoteness dictated how it was colonized by the United States. Hence, Smith notes, Alaska’s climate and icy topography fueled more racism toward Alaska Natives. Because ice was the antithesis of agriculture and settlement, it created a space wherein Western civilization was doomed to crumble (ibid.). Those who lived within such a space, she posits, were deemed to be “racially inferior” and “of pathological transit,” precisely because meager agrarian potential necessarily entailed constant movement (ibid.: 163). “Temperate-normativity” offers a much-needed framework for exploring a wide range of interconnected colonial techniques that lacked their natural habitat, including the fur tax.

I highlight the broader effects of the fur tax by taking a bird’s-eye view, thereby offering a methodology for the reappraisal of (settler) colonial taxation. In doing so, I analyze how a preexisting “civilizing” landscape reshaped the initial revenue-raising function of the tax, turning it into a discrete yet powerful colonizing instrument. The article draws on the work of scholars who have unpacked the sociocultural and political dimensions of the taxation of Indigenous peoples in Canada and the United States (Levitt Reference Levitt2018; Simpson Reference Simpson2008; Reference Simpson2014; Willmott Reference Willmott2020; Reference Willmott2022; Pasternak Reference Pasternak2016; Eaglewoman Reference Eaglewoman2007; Tillotson Reference Tillotson2017; Zahnd Reference Zahnd2022). There, the “logic of elimination”—the blunt replacement of Natives by newcomers (Wolfe Reference Wolfe2006)—empowered tax laws and policies with the ability to make and break one’s socio-political belonging (Zahnd Reference Zahnd2022). Indeed, taxation routinely played an extra-fiscal role in colonial (and postcolonial) locales. “In these contexts,” Miranda Sheild Johansson observes, “paying tax does not confer citizenship, mark inclusion, or signal a state-citizen endeavour to bring about an agreed upon collective world. In fact, the opposite is often closer to the truth” (Reference Sheild Johansson and Stein2023[2020]: 4).

Furthermore, the article seeks to join and add further nuance to the rich interdisciplinary historiography on the significance of colonial tax laws and policies (Rabushka Reference Rabushka2010; Woker Reference Woker2020; Likhovski Reference Likhovski2017; Sheild Johansson Reference Sheild Johansson2018; Bhambra and McClure Reference Bhambra and McClure2022). In colonial Africa, for example, officials often stressed the revenue-raising purpose of taxes, just as Rustgard did with the fur tax (Forstater Reference Forstater and Zarembka2005: 60; Tarus Reference Tarus2004: 61; Redding Reference Redding2006: 24). Yet, tax policies were also imbued with colonizing agendas. The hut and poll taxes lay on skewed sociocultural assumptions about African society (Redding Reference Redding2006). But they, too, sought to “civilize” the colonized population while ushering in capitalism and its cash economy through strict and unforgiving tax liability (ibid.; Forstater Reference Forstater and Zarembka2005: 58–61). As taxpayers, native Africans would subsequently have to change their agrarian practices from subsistence to cash crops (ibid.). Otherwise, they would have to turn to wage labor (ibid.; Latif Reference Latif, Bhambra and McClure2022: 242–45). Similar undertakings happened elsewhere. Circa 1921, in the then British-ruled Solomon Islands, the head tax, too, was tasked with raising revenue and compelling native taxpayers to embrace wage labor and its cash economy (Akin Reference Akin2013: 44–45). And around the turn of the twentieth century, the Dutch colonial government based in Indonesia widely conceived of taxes as “disciplinary tools and transformative devices” (Manse Reference Manse2021: 526).

Unlike the preceding examples, territorial officials did not use the fur tax to try and “civilize” Alaska Natives outright nor compel them to abandon their subsistence way of life. Instead, the work of the tax was much more indirect; its design and intended implementation reflected the ideological input other policies had set in motion. Hence, the fur tax was a catalyst in the “civilizing” process, not a driving force. That being said, one should not dismiss the tax’s sociocultural impact on those from whom it was raising revenue.

Looking beyond the Tax: Hunting Policies in Alaska

When the territory enacted the fur tax on 5 May 1921, the federal government had been regulating hunting for almost two decades, usually to the dismay of most territorial officials. Among them was Alaska Governor John Franklin Alexander Strong. In his 1915 report to the Secretary of the Interior, Strong could not restrain his animosity toward federal oversight, which, he was convinced, had failed to accurately capture the complex and particular profile of the Alaskan wildlife. “There are many peculiarities in the Alaska game law which render it unsuited in many respects to local and climatic conditions in the different geographical divisions of the Territory,” the governor lamented.Footnote 22 The epistemological disconnect between distant federal officials and their locally embedded territorial counterparts was particularly salient when regulating hunting activities throughout the young U.S. territory. Strong, who was well aware that “Alaska is the last great game country in the United States,” advocated for greater local control:Footnote 23 “It is earnestly recommended that the game law be revised so as to eliminate its present objectionable features, and that such amendments be added as will render it more flexible and workable, or, what would be still more preferable, vest the control of the game animals in the Territorial legislature, where, it seems to me, it manifestly belongs.”Footnote 24 Strong would reiterate his recommendation the following year and again in 1918 (Brooks Reference Brooks1965: 4–5).

The 1902 Alaska Game Law

John Lacey, an Iowan (and Republican) congressman and member of the conservationist Boone and Crockett Club (Demuth Reference Demuth2019b: 94–95; Reference Demuth2016: 60–61; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003: 205), introduced the Alaska Game Act in 1902 (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003: 205). Lacey’s goal, which embraced the ethos of the Club (see, e.g., ibid.), consisted in letting game animals and birds “be killed for sport primarily, for food secondarily, but for profit never” (Demuth Reference Demuth2019a: 492).Footnote 25 Accordingly, the law established a comprehensive and very restrictive set of regulations to curb the commodification of several species, including caribou, sheep, bears, walruses, and ducks.Footnote 26 Killing any listed animal outside specific open game seasons, which ranged from one to three months,Footnote 27 could hold serious consequences. Perpetrators committed a misdemeanor and faced a fine and prison sentence.Footnote 28 They also had to surrender their game and could even lose their equipment.Footnote 29 The law restricted how the game could be hunted and provided specific numbers of animals that could be killed during one season.Footnote 30 More importantly, it “prohibited the sale of ‘hides, skins, or heads of any game animals or game birds.’ And it prohibited the sale of game meat ‘during the time when the killing of said animals or birds is prohibited’” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003: 206).Footnote 31

Fortunately, Alaska Natives could escape the law’s central mandate. The U.S. government had granted them the right to “kil[l] … any game animal or bird for food or clothing” so long as no sale ensued during closed seasons.Footnote 32 At first glance, it seemed the law’s drafters had upheld subsistence, thereby recognizing its economic and cultural significance. And yet, the law severely restricted the conditions under which Alaska Natives could hunt and reconcile their way of life with the realities of capitalism. The inability to sell meat or pelts entailed no cash income, which barred hunters and their families from acquiring what was needed to keep hunting (Demuth Reference Demuth2019b: 96; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003: 206). In short, Congress had refused to acknowledge and alleviate what settler colonialism had done to Alaska (Demuth Reference Demuth2019b; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003).

The game law was not just enacted to indulge conservationists, who viewed Alaska as a laboratory where they would make amends for past ecological mistakes on the Western frontier (Demuth Reference Demuth2019a: 492–93). The legal instrument also reflected their profound disgust at Native hunters who, they feared, could not restrain themselves from overhunting. In Alaska, the sentiment was widely shared among non-Natives, and testimonies had sprouted throughout the territory (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003: 205–6; Sherwood Reference Sherwood2008: 108–12). The situation kept escalating and sometimes even led to blatantly biased trials. Circa 1921, for instance, a white jury found a Tlingit man guilty of selling meat from his boat without proof (Sherwood Reference Sherwood2008: 106).

Two years later, an anonymous non-Native Alaskan resident complained, “The game laws of Alaska are being violated every day.” This resident, who was concerned about the declining moose population, unequivocally blamed Natives and their right to hunt during closed seasons. Moreover, he believed he knew why moose were a prime target. “The natives are too lazy to cure salmon for home consumption and for dog food, although our streams abound with salmon. It is so much easier to get moose meat.” “Therefore,” he reasoned, “the natives kill, paying little, if any, attention to whether it is closed or open season.”Footnote 33 Eventually, however, the game law managed to do its job; in the process, it severely impacted the well-being of many Natives (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003: 207).Footnote 34

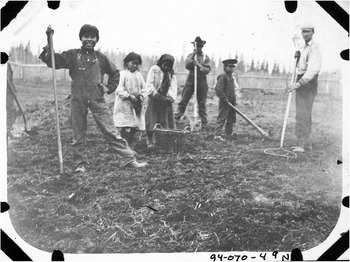

Image 1. Native hunter, circa 1903. Source: Alaska State Library, Historical Collections, Carolyn Burg Photograph Collection, circa 1903, ASL-P357-24.

The 1908 Alaska Game Law

In 1908, when Congress decided that the game law needed an overhaul, the provisions that concerned Natives were left untouched (Sherwood Reference Sherwood2008: 106).Footnote 35 Instead, the 1908 Alaska Game ActFootnote 36 permitted the Alaska Governor to appoint game wardens and register guides,Footnote 37 whom nonresidents henceforth had to hire if they wished to hunt in Alaska (Brooks Reference Brooks1965: 3).Footnote 38 More importantly, the secretary of agriculture was hereby “authorized to adopt regulations to impose even greater restriction [upon Alaska Natives]” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003: 208). A year before enacting the fur tax, the secretary was given full “authority to regulate the taking of fur-bearing animals” (ibid.: 210). Eventually, authority was passed on to Chief Warden Ernest Walker, who was tasked with running the Alaskan branch of the Bureau of Biological Survey (ibid.). Walker and others would unmercifully strive to impact Alaska Natives’ trapping activities. They did so by banning the use of firearms to hunt several species, changing the dates of open seasons for foxes within the northwest portion of the territory, and prohibiting beaver hunting (ibid.: 210–13). Each restriction was a direct attack on Alaska Natives’ socioeconomic wellbeing and cultural identity (ibid.). Each time, non-Natives and Natives themselves voiced their disgruntlement (ibid.). But Natives sometimes had unexpected allies. In his 1918 report to the Department of Agriculture on the Alaska Game Law, Alaska Governor Thomas Riggs contended, “An extremely difficult problem is faced in the question of how far natives shall be allowed the use of game in and out of season.”Footnote 39 “With the Government doing almost nothing for the support of the Alaskan native,” he reasoned, “if the privilege of obtaining food is taken from him his plight will be pitiful.”Footnote 40

Hunting and fishing regulations unambiguously encapsulated an assimilationist policy that sought to slowly but firmly invite Alaska Natives to pursue “civilized” occupations. While subsistence could still be carried out, it would henceforth be curtailed by a legal frame that left little room for Natives to use hunting and fishing activities as substantial sources of revenue. The successive game laws had exacerbated the disconnect between subsistence and capitalism, forcing “uncivilized” Native hunters to either break the law or look for other “civilized” economic pursuits that would take them away from the land.

Agriculture and Alaska: The Quest for Civilization

While trapping and hunting were among the most conspicuous economic endeavors that had been carried out since 1867, alongside canneries, fisheries, and the mining industry, another instrument of Western settler colonialism had been quietly but surely gaining strength. Many wished to replicate what had been done across the lower forty-eight, especially in the West, where farmers and cattle ranchers conquered the frontier (see, e.g., Cronon Reference Cronon1991; Ogle Reference Ogle2013; Rifkin Reference Rifkin1992; Worster Reference Worster2004). This spatial, economic, and sociocultural process, which turned the land into a privately owned commodity, could be deployed through a subtle combination of biological, technological, financial, and legal instruments (see ibid.; and also, e.g., Kloppenburg Reference Kloppenburg2005; Pollan Reference Pollan2006; see generally Diamond Reference Diamond1997; Scott Reference Scott2017). Notably, “techniques of law and land survey,” Meredith Alberta Palmer (Reference Palmer2020: 795) argues, were pivotal in creating a “settler colonial landscape” (ibid.), thereby ushering in agriculture and, in the process, the combined annihilation of Native spaces and assimilation of Native American societies (see generally Cronon Reference Cronon1983).

The desire to develop agriculture in Alaska began almost as soon as the U.S. purchase was finalized (Shortridge Reference Shortridge1977). But the territory had to be better known (and its potential better assessed) before federal officials could deploy any policy. After all, Alaska was nothing like any other U.S. space at the time. Its range of climates and topographical features were strong indicators of a long and treacherous agrarian settlement. And so were its immensity and remoteness from the lower forty-eight. Be that as it may, early reports were generally hopeful and confident that agriculture would have a promising fate if adequately fine-tuned to address Alaska’s uniqueness (see Miller Reference Miller1975; Shortridge Reference Shortridge1977). And while they generally stressed how difficult it would be to turn Alaska into a full-fledged agrarian economy, they consistently praised its potential to support an ever-growing, non-Native population (Banner Reference Banner2007: 304; Miller Reference Miller1975: 17–18; Shortridge Reference Shortridge1977). The reality, however, would quickly cloud the grandest ambitions. After almost two decades of U.S. ownership, Alaska Governor Swineford expressed what had been on the mind of many. “Still,” he admitted, “I do not assume that Alaska, however fertile her soil, will ever take rank as an agricultural district in the light of a production more than sufficient to a supply of breadstuffs for a large population within her own borders.”Footnote 41 Yet, the governor did not lose faith in his U.S. district,Footnote 42 and he added, “But I do assert, and confidently appeal to the future for verification that just so fast as her other great natural resources attract population, her agricultural and horticultural capabilities will come to be recognized and made to yield an abundant food supply for all who come, even to the million.”Footnote 43

While some agricultural potential was undeniable, Alaska still needed to overcome logistical hurdles. To that end, several experiment stations were established (Miller Reference Miller1975: 18–20), with the overarching purpose of shedding further light on what could and could not be done, what was still needed, what kinds of crops could be grown, and finally, to better identify which agrarian pursuits would be worth promoting and carrying out. And to accelerate colonization via agriculture, settlers could purchase homesteads from 1891 onward (Banner Reference Banner2007: 304). However, if aspiring farmers finally had the legal means to develop the soil they had claimed theirs, federal officials quickly realized they would struggle to implement such a policy. First and foremost, laying title over unsurveyed and not easily accessible lands was costly enough to deter those looking for financial opportunities (Miller Reference Miller1975: 20). Moreover, preparing the land for cultivation turned out to be a lengthy and tenuous process (ibid.: 20–21). Finally, remoteness and the lack of reliable transportation also hampered agrarian development (Shortridge Reference Shortridge1978; see also Miller Reference Miller1975), which was doomed to remain physically close to local—and demographically constrained—mining centers and booming coastal areas (Miller Reference Miller1975: 22–25). The construction of the Alaska Railroad, approved in 1914 and completed nine years later (ibid.: 24–26; see also Shortridge Reference Shortridge1978), spurred the settlement of more favorable agrarian spaces in the heart of Interior Alaska, in the Tanana and Matanuska valleys (Miller Reference Miller1975: 24–33; see also Shortridge Reference Shortridge1978). In 1920, one could count 364 farms, but on average each provided only 15.8 acres of cultivated land (Miller Reference Miller1975: 26). Just two of these farms belonged to Alaska Natives (ibid.: 30).

Assimilating Alaska Natives through Farming, Gardening, and Reindeer Herding Policies

The Failure of Farming Policies

The almost total absence of Native-owned farms was hardly surprising, mainly because Alaska Natives were not interested in embracing the profession. For many, farming was just not what they had been used to doing, nor what they henceforth wished to do. No wonder, then, that the first waves of explorers emphasized a lack of agricultural pursuits (Banner Reference Banner2007: 288–89).Footnote 44

Another reason helps explain the staggeringly low number of Native-owned farms. Because homesteading required U.S. citizenship (ibid.: 304), most Alaska Natives, who were not citizens, could not own land that way. Nevertheless, a lengthy, complex, and uncompromisingly ethnocentric process granted citizenship to those found to be “civilized” and willing to assimilate (Zahnd Reference Zahnd2022).Footnote 45 A number of Alaska Natives living in the southeast chose that option (see Alaska Native Brotherhood Reference Hope, Demmert, Brown and Everson1995; Drucker Reference Drucker1958; Metcalfe Reference Metcalfe2014; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003). These Natives, many of whom were Tlingit, viewed U.S. citizenship (alongside assimilation) as a means to obtain civil rights, gain political and economic clout, and secure a better existence than the one they would have had with aboriginal rights (ibid.).Footnote 46

But those who were not U.S. citizens could still own land. In 1906, Congress transplanted the allotment policy to Alaska.Footnote 47 Although the policy still aimed to turn Alaska Natives into “civilized” farmers and acquaint them with private property (Naske and Slotnick Reference Naske and Slotnick2014: 144–45), allotments also cemented property rights which, thus far, had failed to fully protect Native homelands from settler colonialism (Case and Voluck Reference Case and Voluck2012: 117–19).Footnote 48 Still, agriculture, and its potential to “civilize” Alaska Natives, was on the mind of the House Committee on Public Lands (ibid.: 118).Footnote 49 Just as it had been the case within the lower forty-eight (Iverson Reference Iverson2013: 573), federal officials considered agriculture a viable and effective way to “civilize” Alaska Natives (Loring and Gerlach Reference Loring and Gerlach2010: 190). Nevertheless, taming Alaska to help agrarian policies unfold had been an excruciating task. “Only eighty allotments, and most of these in southeastern Alaska, were issued under the act between 1906 and 1960,” Naske and Slotnick point out (Reference Naske and Slotnick2014: 145). If agriculture could not become the acculturating instrument of settler colonialism, federal officials, teachers, and missionaries swiftly decided to field test a policy they hoped could yield similar results. This compromise was gardening.

The Relative Success of Gardening Policies

Scale was the most apparent difference between gardens and farms. More modest in size and purpose, gardening policies could also be implemented in the most remote settlements. Besides, gardens were better suited to Alaska’s size, topography, variety of climates, and small and scattered population. In 1916, at the height of World War I, Alaska Governor John Franklin Alexander Strong discussed the situation and the policy at length. First noting the depleting population of fur-bearing animals, the plunging prices of pelts, the soaring cost of imported food, and the general “scarcity of fish,”Footnote 50 Strong then explained:

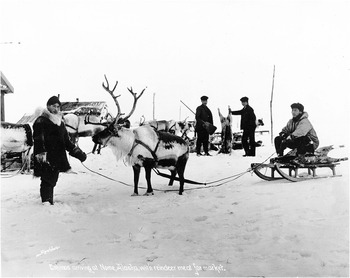

To combat the above conditions, the United States Bureau of Education, through the agency of its teachers in Alaska, issued instructions urging the natives to live as much as possible independently of food supplies and manufactured articles which have to be brought from the outside, and to conserve the native products not only for their own salvation but for the assistance they thereby render the country in the war in which it is engaged. To this end the native, as a farmer, is gradually becoming a factor in the development of the Territory. Through its schools in Alaska, the Bureau of Education is attempting to teach the natives the advantages of having their own gardens in which to raise foodstuffs, not only for their own use, but for the use of miners and others in their vicinity.… It has been difficult in the past to impress upon the natives the advisability of remaining with their gardens until the crops are assured. They have to combat their natural tendency to leave their homes in order to go fishing. While it is necessary for them to obtain fish as well as vegetables, the two can be combined if handled intelligently.Footnote 51

Strong conceived of gardening as a confusing entanglement of seemingly antagonistic policies. Gardens were, most importantly, meant to protect Natives from inevitable starvation. Farming, through gardening, would “save” Alaska Natives—literally, but also figuratively. Indeed, Strong believed gardens would also teach Alaska Natives how to rise above nature and reshape a human-nonhuman relationship settler colonialism had been gradually attacking. Lastly, Native gardeners would help colonization thrive. Whatever gardens would produce, therefore, ought to pave the way for settlement and capitalist pursuits. To Strong, the policy would feed Alaska Natives while enabling their assimilation. That is, gardens would assimilate Natives by subsuming them into the overall settler colonial project of the young U.S. territory. They would do so by rendering their existence and purpose not as citizens of a new polity but as mere food producers (see, generally, Naske and Slotnick Reference Naske and Slotnick2014; Haycox Reference Haycox2002).

Image 2. School garden in Stevens Village, circa 1910. Source: University of Alaska Fairbanks, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Rivenburg, Lawyer and Cora Photograph Album, 1910–1914, UAF-1994-70-49.

The governor also expressed his disbelief in the effectiveness of allotments, which in the lower forty-eight had been the driving force behind the government’s efforts to quell Native Americans’ cultural identity and way of life:

Under the present laws it is possible for natives to acquire allotments of lands in Alaska. To date their usefulness has been rather doubtful. The allotments as now made are really too small for hunting purposes and too large for farms. The native has not yet reached the stage where he can handle intelligently a 160-acre farm, even if he were in a position to clear it and put it under cultivation. Up to the present it has only been possible for him to handle a good-sized garden. After he has learned the lesson well and the advantages of the latter, he will then be in a position to undertake the cultivation of a five-acre farm.Footnote 52

Strong merely echoed what others had said earlier. In 1902, Charles Christian Georgeson, then Special Agent in charge of the U.S. Agricultural Experiment Stations,Footnote 53 published his “Annual Report of the Alaska Agricultural Experiment Stations.”Footnote 54 To advocate for Native gardening, Georgeson enclosed a letter from Unalaklik. “The following letter from an Eskimo, a native of Unalaklik, is of special interest, not only because his report shows him to have been a successful gardener, but more particularly because he is proof that the natives of Alaska are susceptible of civilization,” he contended.Footnote 55 Several decades later, Rustgard himself, who was then retired,Footnote 56 published a book entitled The Problem of Poverty (Reference Rustgard1935), in which he unambiguously expressed his distaste for subsistence. “The real difficulty encountering in any effort to civilize the aborigines in the various countries is their inability to think and plan for the future,” he first lamented (ibid.: 19). “They are,” he added, “very much like beasts of prey, which eat their fill when they have made a killing and then go hungry until they have made another catch” (ibid.: 19–20). Rustgard then turned to the case he knew best, that of Alaska Natives: “The natives of Alaska are considerably farther advanced in civilized thinking than the aborigines throughout most of the rest of America, but they have persistently continued to resist every effort to get them to till the soil, for the very reason that they insist upon enjoying the fruit of their labor as soon as it is earned, being unwilling to sacrifice their present comfort for any future boon” (ibid.: 20). But the former attorney general was not done. “So insistent are they upon immediate enjoyment of the earnings of their labor,” he continued, “that they refuse to cut wood for the schools maintained for their benefit by the United States Government, because it has required about three months after the work was completed to get the pay warrant from Washington” (ibid.). “So strongly is this trait ingrained in the Indian character that no amount of education had been able to shake it perceptibly, much less uproot it,” Rustgard reasoned (ibid.: 21).

In light of the preceding statements, it is only logical that gardening was widely conceived as a powerful and promising acculturating device, since gardens offered a smoother introduction to full-time agrarian pursuits. Many Natives had been growing native and non-native crops since the early 1900s, generally under the guidance and oversight of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and federal officials (Loring and Gerlach Reference Loring and Gerlach2010). Conversely, others had been gardening long before the United States purchased Alaska (ibid.: 186). But gardens would never eradicate nor even compete with subsistence activities. Instead, as Loring and Gerlach explain, gardens “were effectively used to fill an important niche in local foodways, contributing an additional measure of economic diversity and therefore resilience to these communities” (ibid.: 184).

The Effectiveness of Reindeer Herding Policies

Gardens were not the sole policy that sought to curb foraging. In 1891, the United States launched a program that would eventually attempt to turn the Iñupiat into full-time pastoralists (see, e.g., Stern et al. Reference Stern, Arobio, Naylor and Thomas1980; Case and Voluck Reference Case and Voluck2012: 212–15; Emanuel Reference Emanuel2002: 52–54). That year, however, federal officials first sent sixteen Siberian reindeer to two Aleutian islands (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Arobio, Naylor and Thomas1980: 15). The following year, Port Clarence, located on the edge of the Seward Peninsula, received 171 animals (ibid.). From then on, numbers would keep increasing, eventually leading to the advent of a thriving community of Iñupiat reindeer herders (see ibid.). In 1914, for instance, the region comprised sixty-five herds, totaling almost fifty-eight thousand reindeer.Footnote 57 Two-thirds were owned by Alaska Natives, who generally oversaw a modest herd.Footnote 58 But in that year, revenues reached nearly $78,000.Footnote 59 When the Territory of Alaska enacted the fur tax, the number of reindeer had burgeoned to 216,000.Footnote 60

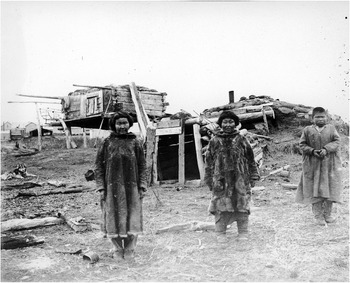

The idea to import domesticated reindeer came from Reverent Sheldon Jackson, then General Agent of Education (see, e.g., Stern et al. Reference Stern, Arobio, Naylor and Thomas1980; Emanuel Reference Emanuel2002: 52–54; Willis Reference Willis2006). Since starvation had been looming large over the area, mainly because non-Native commercial hunting of seals and walruses was in full swing, Jackson thought the animal could help the Iñupiat secure a much-needed, steady source of food (Demuth Reference Demuth2019b: 146; Case and Voluck Reference Case and Voluck2012: 212; see also Stern et al. Reference Stern, Arobio, Naylor and Thomas1980). The federal government had intended to make reindeer herding an exclusive Native occupation since its inception. In 1937, the policy was firmly translated into law with the passage of the “Alaska Reindeer Act” (Case and Voluck Reference Case and Voluck2012: 213; Cohen Reference Cohen1942: 409–11). But Jackson also had a much less humanitarian goal in mind. This goal, which coalesced with that of agrarian policies, focused on Alaska Natives’ way of life—that is, on subsistence activities and their underlying aversion to fixity and private ownership (see Case and Voluck Reference Case and Voluck2012: 212–15; Demuth Reference Demuth2019b: 147; but see Goldschmidt, Haas, and Thornton Reference Goldschmidt, Haas and Thornton1998). After agriculture and gardening, reindeer herding offered the next best opportunity to spread capitalism’s core tenets throughout Alaska.Footnote 61 “[D]omestic reindeer,” Bathsheba Demuth points out, “could be owned” (Reference Demuth2019b: 147).

Image 3. Native reindeer herders arriving in Nome to sell reindeer meat, circa 1903–1907. Source: Alaska State Library, Historical Collections, Beverly Bennett Dobbs Photo Collection, ASL-P12-178.

Reindeer herders, officials hoped, would be propelled out of subsistence and introduced to capitalism through “production” (ibid.), thus becoming “capitalist citizens” (Demuth Reference Demuth2019a: 500).Footnote 62 In 1915, Alaska Governor Strong explicitly praised the assimilative function of the policy. “But wherever the reindeer have been introduced in Alaska the industry has had a beneficial effect upon the native people,” Strong marveled.Footnote 63 “It has taught them to be industrious. It has had a tendency to educate them in the industrial arts of the white man. It has taught them to assume responsibilities, increased their activities, and raised them materially in the ways of civilized life.”Footnote 64 Eventually, the policy would fail to deliver its promises. Fast forward two decades, General Reindeer Service Superintendent Joseph Sidney Rood despaired that Natives’ “economy, attitudes, habits, capacities have been the greatest problem, dwarfing all others, in creating reindeer businesses.” What struck him most was the lack of Native entrepreneurship “on this Bearing sea coast,” especially agrarian, which he believed represented the pinnacle of one’s “civilized” advancement.Footnote 65

For officials such as Rood, farming remained the panacea for assimilation. Meanwhile, reindeer herding offered an acceptable compromise, though the policy could hardly spread beyond the tundra. And while Native entrepreneurs relied on an existing market, so did Native wage workers, who needed employers. Gardens were less affected by local conditions but made any mass-scale “civilizing” project hopeless. Policies often were deployed pragmatically. Alaska’s geography, climates, sparse population, and “uneven” (Smith Reference Smith2010) economic development dictated where and under what guise settler colonialism would unfold. These policies, along with the successive game laws, provided a sociocultural, economic, and legal landscape that curbed subsistence activities. Because the fur tax was part of that landscape, one should treat it as a not-so-neutral legal instrument.

When Space Gets in the Way of Settler Colonialism: Tax Implementation in Alaska

How the tax was collected provides much-needed insight into the settler ideology of the territory. To be sure, territorial officials could have hired and sent tax collectors all over Alaska to try and defeat its geography. In fact, they were no stranger to this type of spatial deployment in the name of fiscal efficiency and settler colonial expansion, alas—and once again—at the expense of Natives. For example, the school tax, a gendered head tax that financed Alaska’s segregated public school system, relied on an army of collectors.Footnote 66 While many remained within incorporated towns and school districts, some occupied much vaster territories (see Zahnd Reference Zahnd2021).

But collecting the fur tax depended on trappers’ schedules and ability to catch animals. And despite substantial efforts, there was no guarantee that tax collectors would always report successful campaigns. The reason was apparent: while the school tax consisted of a one-time and fixed contribution, the fur tax was inherently tied to the number and type of pelts trappers had obtained. Their hunting skills, not their cultural identity or mere (male) existence, triggered tax liability. This logistical glitch had precedence: in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Siberia, the tsar used Indigenous peoples’ unmatched trapping skills to obtain the highly sought-after sable furs, then to be sold across Europe (Slezkine Reference Slezkine1994; Willerslev Reference Willerslev2012; Willerslev and Ulturgasheva 2006/Reference Willerslev and Ulturgasheva2007). In broad outline, hunters of age to be productive fur suppliers had to pay a yearly tribute in sables (Fisher Reference Fisher1943: 55-57; Slezkine Reference Slezkine1994: 22; Willerslev Reference Willerslev2012: 41). The iasak (or yasak) was not correlated to one’s actual catch, nor was it particularly mindful of the ever-declining sable population (see Willerslev Reference Willerslev2012: 41; Willerslev and Ulturgasheva 2006/Reference Willerslev and Ulturgasheva2007: 83–84). As Yuri Slezkine (Reference Slezkine1994: 22) explains, “On the one hand, the success of a voevoda [i.e., collector] was measured by the number of furs he procured—and so, naturally, was his personal fortune. On the other hand, the size of the iasak that the native northerners delivered depended on their hunting luck, need for Russian goods, and migration routes.” Hence, collections were doomed to encounter significant variations from one year to the next and from one collector to the other, which was unacceptable for a state that relied heavily on this revenue (Willerslev Reference Willerslev2012: 41).Footnote 67

In Alaska, the overwhelming human and economic cost associated with this way of collecting the fur tax could far outweigh expected revenues (see Scott Reference Scott2017: 135). Roads were scarce, railways even more so, and resorting to tax collectors who had seldom ventured off the beaten paths thus was highly incompatible with most trapping locales’ natural environment. When the territory enacted the fur tax, space had not been vanquished yet. “There are still considerable parts of Alaska which are out of communication except by the old tortuous boat or sled travel which, if for no other reason than for judicial needs, should be served,” Governor Riggs lamented in his 1919 annual report.Footnote 68 Interior Alaska, where trapping activities were routine, encapsulated Alaska’s feral wilderness particularly well. Circa 1910, the U.S. Census Bureau depicted a land still hostile to colonization. “The enumerator for the Chandalar district,” for example, “crossed and recrossed the Arctic Range, traveling above the timber line for eighteen hours at each crossing. At no time after he left Fairbanks did the thermometer rise above 30° below zero. Two of his dogs froze to death, and he himself froze portions of his face several times, and at one time dropped into 6 feet of open water, nearly losing his life. He traveled in many places where no white man had ever been before.”Footnote 69

Implementing the fur tax within the most remote confines of trapping territory was indeed doomed to encounter a significant hurdle. That hurdle was Alaska’s “vast size, difficult terrain, and lengthy coastline” (Naske Reference Naske1998: 164), not to mention its merciless weather and countless islands. Tax collectors would need to brave harsh terrains and extreme weather conditions, often on foot, to occupy a space that territorial officials often conceived of in terms of mere distance (Scott Reference Scott2009: 47). Surely, game wardens, who guaranteed the effective implementation of game regulations throughout Alaska, were evident and natural contenders. Some territorial officials shared this opinion. Soon after the enactment of the school tax, for example, Governor Riggs quickly realized that he would need their help to cover as much ground as possible. So, he did not wait long to appoint game wardens such as Andrew Berg, mainly in the name of pragmatism. “In appointing you as school tax collector,” Riggs explained to the perplexed man: “we simply followed the practice established this year of appointing all game wardens and special officers not with the idea of imposing additional duties upon them, but primarily to afford them an opportunity to make a little money in collecting the tax while on a trip made for the purpose of investigating game conditions or possible violations, the object being to avoid any special trips for the collection of the tax except when necessary.”Footnote 70

Riggs then discussed the conditions under which the game warden should levy the school tax. “Of course,” the governor commented, “if all those subject to the tax have paid, then there is nothing for you to do, but if there are some that have not, you could no doubt get them while traveling in your capacity as game warde[n].”Footnote 71 Riggs’s decision to enlist the game wardens he had at his disposal was cunning. They knew the land better than anyone else, already patrolled the area relentlessly, and were known by the locals—all ingredients that guaranteed a smooth and efficient implementation of the tax while cementing the colonization of the frontier, albeit within limits (Zahnd Reference Zahnd2021).

Eventually, territorial officials in charge of the fur tax did not choose to mimic to the letter what their predecessors had done with the school tax. Instead, the U.S. commissioners were responsible for collecting the tax. Accordingly, section 10 stated, “each trapper or other person taking pelts of wild fur-bearing animals shall pay to the Commissioner in the district where he resides or where his principal business is conducted, the license tax provided for in Section 3 of this act [i.e., license taxes that were different for each species].”Footnote 72 Further, each trapper’s overall tax liability would be due by “the first day of August of each year,” which facilitated collections.Footnote 73 But the game gardens would not remain idle. Rather, they, along with U.S. marshals and deputy marshals, would assist the commissioners with some aspects of the implementation.Footnote 74

On Tax Law as Settler Colonial Tool: Reappraising the “Neutral Tax”

Though seemingly neutral and mundane, the form of the tax can help us decipher the broader intentions of Rustgard and other territorial officials and better assess the actual effects the tax had on Alaska Natives.

Tax liability was not always a hopeless and inescapable outcome. Trappers did not need to pay the tax when “pelts [were] sold to licensed fur-traders in the Territory,”Footnote 75 which meant that Natives could escape the tax only if they dealt with specific individuals, the “fur-buyers,” who themselves purchased an annual license and would also be liable for the portion of the tax associated with each type of pelt. In fact, fur-buyers were the nexus through which the tax was meant to be collected. They could be “stationary,” that is, “maintain[n] a permanent, fixed place of business within the Territory, at which … [they] dea[l] in furs and to which the pelts … purchased are shipped before being placed upon the market.”Footnote 76 Or they could be “itinerant” and not “maintain a permanent, fixed place within the Territory for dealing in furs, and to which all … [their] pelts are shipped before being placed on the market.”Footnote 77 In the latter case, the fixed license fee was three times higher, culminating at $150.Footnote 78 Such was the price to pay for mobility and more significant economic prospects. Attorney General Rustgard himself confirmed the centrality of fur-buyers. He reminded Young, “You will observe the purpose is to put a tax on all pelts, and inasmuch as such a tax has to be paid by a licensed fur buyer, it is not necessary for the trapper to pay a tax on pelts thus disposed of.”Footnote 79 The second tier of the tax was meant to be paid once. Through this lens, one could view the exception as having a practical aim: to avoid double taxation.

And yet, the sociolegal and political environment surrounding the tax helps unpack a sharply different reading of its implementation, especially toward Natives. First and foremost, trappers, if they wished to avoid tax liability, were not free to choose with whom they traded. Further, those who had decided not to sell their pelts to licensed fur-buyers and instead pay the tax faced greater control. Section 10 of the fur tax act mandated them to “deliver” the tax to the abovementioned commissioner, “together with a correct statement of the number and species of the pelts on which such tax accrued.”Footnote 80 This requirement mirrors Section 9’s prerequisite, “Every person trapping fur in the Territory shall keep a correct record in permanent book form of all the pelts taken by him and to whom and when sold or otherwise disposed of, and shall send a true copy of such record to the Commissioner and Ex-officio Recorder in the district in which he resides or in which he carries on the principal part of his business in the Territory.”Footnote 81

These requirements—the payment of the tax and the communication of the record, which had to be done “before the first day of August of each year”—reinforced what Sean Redding calls “the ritual of interaction” that eventually sustained “the maintenance of state control” (Reference Redding2006: 13–14). In the South African context, these “rituals of rule,” she notes, “reinforced and reenacted the subordination of Africans to the colonial state” (ibid.: 10). The implementation of the Alaska fur tax certainly achieved similar results. Moreover, colonial control was continuous. The record, which “shall show the species of each pelt with sufficient distinctness to determine the tax payable thereon,” could “at all times be open to the inspection of the game warden and United States marshals.”Footnote 82 And even more drastically, section 13 authorized “a game warden, marshal or deputy marshal or other person” to apply for a search warrant and look for pelts they suspected had not been taxed, virtually wherever they pleased.Footnote 83

Records one needs to build, keep, share, and show upon request, such as the one prescribed by the fur tax act, are not anodyne instruments. “The state,” James Scott writes, “is a recording, registering, and measuring machine,” and peasants, he adds, had long grasped the magnitude of that reality to the point where they were wary of documents and record keeping (Reference Scott2017: 139–40). Their association with a government’s “control” over the Indigenous subalterns is even more striking in a settler colonial context (Luker Reference Luker2017: 112). In fact, records and the “colonial numbers” they would generate fueled the Territory of Alaska’s “fiscal surveillance” (Willmott Reference Willmott2023), ipso facto contributing to the combined colonization of hunting spaces and process of “civilizing” Native trappers. In other words, taxation would provide more data to the U.S. territory (see also Manse Reference Manse2022a: 420–21). The record Native trappers would have to fill out and carry at all times constituted an extension of territorial power.Footnote 84 Record-keeping indirectly “civilized” trappers by turning them into rational actors who would have to quantify what they hunted. Most importantly, written records would consistently reconnect hunting with taxes and, by extension, would condition one of the most salient features of their cultural identity to their obligations as taxpayers and subjects of a settler polity.

Image 4. Native dwelling and cache near Bethel, circa 1902. Source: Alaska State Library, Historical Collections, Bethel area trading post, Moravian Mission and Native Culture Photograph Collection, 1902, ASL-P268-04.

Kyle Willmott posits that taxation is “a form of governmentality” (Reference Willmott2022: 8), that is, the Foucauldian process that manufactures “subjects through circulatory power tactics and fields” (Cattelino Reference Cattelino2006: 701). In the U.S. settler colonial context, Thomas Biolsi (Reference Biolsi1992; Reference Biolsi1995; Reference Biolsi2018) has unpacked the ways governmentality was imbued with U.S. laws and policies and often took myriad forms. Its purpose, however, has been consistent throughout history: whenever federal and territorial officials deployed governmentality toward Native Americans, the expected result was to foster control, marginalization, or outright assimilation (see, e.g., Biolsi Reference Biolsi1992; Reference Biolsi1995) through “forms of power that take the population as the target of governing” (Biolsi Reference Biolsi2018: xiv). Maarten Manse (Reference Manse2021: 553) adds that taxation is an ingredient of what David Scott (Reference Scott1995) calls “colonial governmentality.” Accordingly, colonialism unleashes “a form of power” to instill “a new form of control,” thereby “oblig[ing] new forms of life to come into being” (Manse Reference Manse2021: 553, citing Scott Reference Scott1995: 140).

So did the fur tax function, sharing similarities with other colonial counterparts. For instance, Dutch colonial taxation in Indonesia reflected this paradigm. Taxes were meant to raise revenue but also to reshape the population—socioculturally and economically (Manse Reference Manse2021; Reference Manse2022a; Reference Manse, Bhambra and McClure2022b). “Taxes were actively used as governmental tools or disciplinary instruments to correct behaviours, instil [sic] productivity, and shape obedient, ‘civilized’ taxpaying subject-citizens living according to the patterns desired by the state,” Manse states (Reference Manse2021: 529). The requirement that Alaska Natives keep a record in English was perhaps the most blatant form of governmentality. In 1920, roughly two-thirds of Natives over age twenty-one could not “write in any language.”Footnote 85 Meanwhile, only a third of Natives over age ten could speak English.Footnote 86 The ability to keep a record in “permanent book form”Footnote 87 was itself a means to subtly distinguish between “civilized” and “uncivilized” trappers.Footnote 88

Rustgard contended that non-law-abiding Native trappers would not necessarily face terrible consequences. “The officials of the Territory fully realize that information concerning the various provisions of this act may fail to reach many people affected by it, and others may have difficulty in understanding it or in complying with its provisions.”Footnote 89 “This,” he stressed, “will be more especially true of natives.”Footnote 90 The attorney general then explained how he wished to implement the tax. “For this reason, the utmost caution should be exercised lest an injustice be done those who violate the terms of the law unintentionally,” he asserted, adding that “any doubt as to whether or not a person has unintentionally violated the law should be resolved in his favor.”Footnote 91 Though benevolent, Rustgard’s statement was a subtle way to spread governmentality throughout a space he could not yet control fully. The attorney general, then, insisted that the tax “should be enforced with a view of creating as little friction as possible.”Footnote 92

Rustgard’s wariness was not unsubstantiated. As several scholars (e.g., Manse Reference Manse2021; Redding Reference Redding2006) have pointed out, colonial taxation did not always enable “new forms of life to come into being” (Scott Reference Scott1995: 193). In colonial Africa, revolts, disobedience, and acts of resistance of various scales routinely erupted (Redding Reference Redding2006; Crush Reference Crush1985; Tarus Reference Tarus2004; Bush and Maltby Reference Bush and Maltby2004). And even though they gravitated around tax discourse and grievances, they were deeply rooted in Africans’ refusal to be colonized (Redding Reference Redding2006). Colonial Solomon Islands and Indonesia, too, experienced such reactions (Akin Reference Akin2013; Manse Reference Manse2021). Similarly, there had been precedents while Alaska was a Russian colony but also more recently (Zahnd Reference Zahnd2022). Natives who lived in trapping territories and had experienced less contact with colonization tended to reject all forms of territorial power, including taxation.Footnote 93 In 1921, for instance, Deputy Collector of Customs Mr. J. J. Hillard, based in Eagle, wrote to the governor. “This school tax was paid by two native boys who are working as deck-hands on Yukon river steamers,” he explained.Footnote 94 “They had no option on the matter, the Purser deducting it from their pay, and are very voluble in their protests, at least one of them is—the other stutters,” he added.Footnote 95 Concerning the fur tax, on 5 January 1922, the territorial treasurer wrote to Rustgard because he felt compelled to share a letter he had received from Boyd, U.S. commissioner stationed in Fairbanks. “Regarding the matter of the collection of license taxes on furs—will say that our population here do [sic] not seem inclined to pay this tax, and this office is not in a position, having neither the time or disposition, to force the collections,” Boyd despaired.Footnote 96 The commissioner did not mention whether rogue trappers, fur-buyers, or fur-farmers, if not all of them, had prompted him to reach out to the treasurer. If trappers were indeed on his mind, U.S. census data indicate that many could have been Natives.Footnote 97 Eventually, Native trappers would, by and large, be impacted by the tax that contributed to making them “civilized” in the eyes of the territory—first as taxpayers, second as reformed hunters, and third as manufactured gardeners, reindeer herders, or wage workers.

Conclusion

The form of the tax did not remain static for long. On 15 February 1923, Alaska Treasurer Walstein G. Smith released his biannual report for the years 1921–1922. According to him, implementing the tax had caused “numerous problems,” including reluctance to comply. The tax, Smith insisted, “will have to be rewritten and amplified in many particulars.”Footnote 98 His proposal did not take long to find support among territorial officials and lawmakers, and a few months later a novel fur tax was enacted.Footnote 99 One change would directly impact Alaska Natives. While the 1921 fur tax fully applied to trappers, the new version spared them almost entirely. For the most part, trappers would no longer be required to pay the second tier of the tax, which was still based on each type of pelt.Footnote 100 By focusing the tax on those who bought and sold furs for a living, were less numerous than trappers, and were easier to locate, territorial officials had learned from their past mistakes—the potential revenue generated by the tax needed to outweigh the cost of its implementation. If the territory could not track individuals in the wilderness, it would hover over those who turned pelts into commodities. And by changing the scope of the tax, they also changed how it helped spread settler colonialism.

The 1923 version of the tax severed its direct connection with other assimilationist policies because Native trappers would disappear from its scope, and yet that disappearance could accelerate marginalization, because Native trappers would lose their status as law-abiding taxpayers. That is, Native trappers had lost a compelling reason to request (and obtain) more rights as taxpaying citizens (see Zahnd Reference Zahnd2022). Under this new fiscal regime, trappers had become “uncivilized” ghosts that supplied pelts but lacked fiscal existence. They had become an anomaly in territorial officials’ quest to turn Alaska Natives into “civilized” farmers, gardeners, reindeer herders, or wage workers. But the 1923 fur tax was short-lived. Both the “changed business conditions in the fox farming industry” and the enactment of a new game law in 1925 complicated collections (and threatened future revenue), and thus precipitated its demise.Footnote 101 On 26 April 1927, the Territorial Legislature repealed the tax once and for all.Footnote 102

In conclusion, this vignette of Alaska’s sociolegal history warrants the following observations. Above all, it seems evident that the fur tax was never designed to deploy the young polity’s ambitious agenda alone. On the contrary, it was part of this agenda, bolstering assimilationist hunting, agrarian, and pastoral policies. This interconnectedness was not unique to Alaska. For example, the South African hut tax was not alone in attempting to compel men to become wage workers, even though officials had enacted the tax partly to help them achieve that goal and raise revenue (Redding Reference Redding2006). Indeed, Redding observes, African men abandoned subsistence agriculture because of “a combination of environmental, cultural, and demographic factors” and not just because of the tax (ibid.: 161). Conversely, some taxes and their exceptional revenue-generating abilities were the driving force behind full-scale colonial projects. Such was the case of the Siberian fur tax, the iasak. “In fact,” Rane Willersev points out, “the whole colonial administration, its construction of fortresses, its military strategic deployments, its acquisition of new territories, and its categorization of the indigenous peoples into administrative tribes and clans, was guided by the collection of the yasak” (Reference Willerslev2012: 41).Footnote 103

Neither was the tax meant to become a prime fiscal instrument. Its scope was too narrow, and the industry it targeted did not bear comparison with fisheries, canneries, or mining activities. The Territory of Alaska welcomed the extra revenue but could have survived without it. Yet the tax participated in the territory’s quest to “civilize” Natives. It did so covertly, momentarily, and almost serendipitously. Its colonizing potential, unable to operate alone, needed a suitable environment in which to thrive. Thus, the brief existence (1921–1927) of the fur tax, especially while it was an active agent of colonization towards Native trappers (1921–1923), should not undermine the overall point this article has worked to make. Namely, this case study suggests that within many, if not most, (settler) colonial spaces, political and sociocultural ideologies can alter the initial revenue-raising function of taxes.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Catherine Albiston, Seth Davis, Mark Gergen, Florian Grisel, Ariela Gross, Shari Huhndorf, Mandy Izadi, Alexandre (Sandy) Kedar, Tony Platt, Adam Smith, Kara Swanson, Leti Volpp, and Elizabeth Walsh for their comments and suggestions. At CSSH, I am grateful to David Akin for his support and wonderful editing, to the anonymous reviewers who provided extremely thought-provoking comments, and to Paul Christopher Johnson and Geneviève Zubrzycki for their support. Lastly, I thank the Rothermere American Institute, University of Oxford, for giving me the time and space to work on the article while I was a Fellow-in-Residence.