1. Introduction

How do interpretive agents, such as judges on the benches of international courts, react to interpretations of international law that appear to be in consonance with (or contrary to) their own moral preferences? Do they reject moral considerations as potentially ‘extra-legal’, as would be recommended by an exclusivist-positivistic perspective? Or do they simply accept that such considerations exert an inevitable influence, per a critical legal studies perspective on interpretation in international law?Footnote 1 Or would they positively welcome a moral influence (provided it took the correct form, anchored in legal theory), as an inclusivist perspective would suggest? We seek to address these questions by developing a novel experimental linguistic approach to interpretation in international law, based on a working assumption that the linguistic approach of experimental pragmatics can be usefully applied to international law and, in particular, to questions of (treaty)Footnote 2 interpretation. Our aim here is to provide – to our knowledge, for the first timeFootnote 3 – preliminary empirical evidence of the influence of moral factors on treaty interpretation and to explore the consequences of this finding.

This article presents the results of five experiments undertaken to test three hypotheses related to the aforementioned questions. We applied different treatments (varying levels of moral content in the experimental interpretation scenario) and drew comparisons between two samples, laypersons vs. international law experts, who were exposed to a series of legal-interpretation scenarios and were asked to share their reactions. The configuration of each experiment was as follows: (i) laypersons and a morally-neutral scenario; (ii) laypersons and a morally-non-neutral (desirable) scenario; (iii) experts and a morally-neutral scenario; (iv) experts and a morally-non-neutral scenario; and (v) laypersons and a morally-non-neutral scenario, where the interpretation to which they were exposed was in stark misalignment with their personal values.Footnote 4 These configurations are described in more detail in Sections 4.1.4–8, infra. By comparing the responses of the two samples, we could examine whether interpretive agents in international law interpret treaty language under the ‘ordinary meaning’ maxim in a manner comparable to that of laypersons. In other words, we checked whether the laypeople’s understanding of legal rules is comparable to international lawyers’ understanding of these same legal rules.

We tested the above by applying linguistic categorizations developed for everyday language situations to international legal contexts. If found to be applicable, these categorizations could also provide a more precise vocabulary with which to describe interpretation than the current state of the debate in international law.

Adding moral considerations enabled us to examine whether these influenced the participants during the process of interpretation. Specifically, we could observe how the participants responded when interpretations happen to match their own moral convictions or were contrary to them.

In relying on linguistics and experimental research, we draw from, and contribute to, two recent trends in international law scholarship that complement classical doctrinal studies on interpretation in international law.Footnote 5 First, scholars have increasingly drawn on a variety of linguistic approaches to scrutinize phenomena in international law.Footnote 6 Among others, they have examined the semantics–pragmatics distinction and its usefulness in describing and discussing interpretation in international law.Footnote 7 Second, scholars have begun to engage in experimental research in international law,Footnote 8 whether in the context of so-called behavioural international law and economics,Footnote 9 research into ‘nudging’,Footnote 10 or the scrutiny of the psychology and cognitive dimension of international law.Footnote 11

In the following sections, we first identify the primary approaches to treaty interpretation in current international legal scholarship with regard to the influence of moral considerations on interpretation: a formalist approach (in a strict and a nuanced version); a critical legal studies-based approach; and a legal theory-based inclusivist approach. Based on the discussion of these three perspectives, we formulate the hypotheses behind our experiments. We then explain the overall experimental design and the procedure that sample participants were asked to follow. For this purpose, we undertake a short excursus into linguistics – specifically, semantics and pragmatics, experimental approaches, and the typology of pragmatic interpretations that we use in the present research. Next, we examine each experiment in turn, discuss the empirical results, and explore the conclusions that can be drawn, taking into account certain inevitable design limitations. Our evidence points to a remarkably clear influence being played by moral considerations in the interpretation of international law, calling for a renewed look at the institutional settings in which international law is interpreted. We hope that our research findings might constitute an incentive to evaluate again the practices of interpretation themselves. Moreover, we hope that our findings will reveal that this sort of research can be extremely useful to international lawyers and thereby will constitute an incentive to further future experimental research. Finally, in the Conclusion, we discuss the relevance of our findings for future research dealing with international legal interpretation.

2. Moral factors and the interpretation of international law

While accepting that it would be impossible to do justice here to the rich debate in international law that reflects a multitude of perspectives on treaty interpretation, we nevertheless need to develop testable hypotheses for our experiments. In short, in order to be able to test, in context, what is generally happening during interpretation, we first need to be able to establish what international lawyers think happens (and should happen). Therefore, we reduce this highly complex debate into deliberately simplified positions: certain considerations outside of a treaty text, such as morals, either do or do not exert an influence on agents’ interpretation of international law, and any moral influence is either welcomed or rejected. Consequently, without any claim to completeness, the following sections aim to establish three archetypical perspectives on how interpretation operates and what should be expected under each perspective.

2.1 A formalist approach: Strict vs. nuanced

For our present purposes, it makes sense to discuss strict vs. nuanced formalist perspectives jointly, as fundamentally similar expectations of interpretation processes result from them. Put succinctly, a formalist approach argues that moral considerations should be excluded as non-legal. Under a strict formalist perspective on interpretation, law is perceived as a determinate system with an immanent rationality that makes it possible to provide the ‘compass points’ for its own successful interpretation.Footnote 12 An interpreter is, thus, able to successfully interpret the law by taking into account the prescriptions of the law itself about interpretation – for example, with regard to treaty interpretation in international law. Hence, only legal elements that are permitted by international law are to influence the process of interpretation and ought to lead to one correct result.Footnote 13 The well-known prescription of Article 31(1) of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT)Footnote 14 states: ‘A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.’ Under this view, norms such as Article 31(1) VCLT provide tools to ‘find’Footnote 15 the ‘true’Footnote 16 meaning of a legal provision among several possible candidates. Interpretation is thus a matter of discovery, not norm-creation.

Alongside a strict formalist position, there is an – arguably, now widespread – acknowledgment of the difficulties posed to a formalist perspective on interpretation by the under-determinacy of language itself as the vehicle through which the law’s commands are conveyed.Footnote 17 This acknowledgment has given rise to the nuanced perspective on interpretation or what could be termed the ‘middle-of-the-road’ approach of ‘determinability’.Footnote 18 Typically, under this approach, the legal system is seen as a ‘frame’Footnote 19 offering several choices of interpretation in a concrete case. Attention then turns to the legal system’s agents and their discretion as well as the rules that constrain that discretion and provide standards for a correct decision.Footnote 20 Here, then, interpretation is not an act of mere discovery but an act of cognition requiring an active decision by the legal agent in question. Nonetheless, the agent is constrained by the law during the interpretive process, and elements that are considered extra-legal should not play a role.

For our purposes, under both of these formalist perspectives, experiments should yield the result that the law and its specific phrasing exert a significant impact on interpretative decisions and their assessment by others. According to the ordinary-meaning maxim, we should expect some commonalities between the understandings of laypersons and those of experts. ‘Ordinary meaning’ is defined in the doctrine not as ‘any layman’s understanding’Footnote 21 but as what a person ‘reasonably informed on the subject matter of the treaty’ would understand under the treaty’s terms.Footnote 22 Following this logic, if we provide laypersons with a reasonable amount of information on the subject matter of a treaty, their understanding should broadly align with that prescribed by international law experts as ordinary meaning. A formalist approach would also suggest that experts should be less likely to be influenced by factors that would be considered extra-legal, such as moral factors.

2.2 A critical legal studies approach

What we have described thus far are two facets of an approach to interpretation, both of which are fundamentally based on the (somewhat) idealistic vision of an objective treaty interpreter striving at all times to act rationally. At the risk of gross overgeneralization,Footnote 23 international lawyers adhering to tenets of critical international legal theoryFootnote 24 would typically suggest that this ostensible pursuit of rationality or objectiveness is not what happens in reality and that a more realistic view of the praxis of international courts and judges is needed. Regarding moral considerations, then, a critical legal studies approach would suggest they are an inevitable part of the functioning of international law and must therefore be acknowledged as an inherent aspect of interpretation practice.

In this diverse strand of research,Footnote 25 scholars discussing the ‘indeterminacy’ of international law have spoken out with particular vigour against oversimplified accounts of the operation of international law in contexts such as that of interpretation. Rarely, however, does the indeterminacy critique go so far as to question the very idea of legal language having any intrinsic meaning at all. Indeed, this critique is not truly or exclusively about linguistic matters and meaning, but that, rather, it points to broader structural issues that can also arguably render the law indeterminate.Footnote 26 Only some (but not all) voices subscribe, for example, to the view that ‘there is only the meaning which social practice determines’.Footnote 27 On that premise, social acceptance would thus be pivotal in understanding the current meaning of treaty texts, and textual arguments could not stand in the way if what is socially accepted changes over time.Footnote 28

Numerous other views hold that the point about indeterminacy is not that it alludes to the ‘semantic open-endedness’ or ambiguity of the words of the language of international law.Footnote 29 It is ‘stronger’ than that: even when a rule of international law can scarcely be considered vague or ambiguous at all, the wording of a norm can be set aside if the ‘very rationale’ of the rule demands it.Footnote 30 Indeterminacy is, thus, a structural feature and not a ‘deficiency’ whereby any course of action – even deviation from an apparently clear rule – can be supported by cogent legal arguments in international law. Therefore, the rules of international law can fulfil their purposes in unpredictable future circumstances in which they risk being over- or under-inclusive.Footnote 31 There is thus a gap between the available legal materials and an actual legal decision that is filled by international law’s fundamentally political nature – that is, the practice of law as ‘politics’.Footnote 32 Even scholars with a (nuanced) positivist mind-set observe a practice in international law that refers constantly to positive international law and its sources but mixes it eclectically with political and moral considerations.Footnote 33, Footnote 34

A poststructuralist approach transposes these thoughts about the nature of the law to the context of language and (treaty) interpretation. Accordingly, there is little room for any doctrinal theory of interpretation, including, for example, Article 31(1) of the VCLT. As Rasulov has observed, no reading of a text is without interpretation, and no act of reading is like any other or will produce the same understanding.Footnote 35

The overall inferences that can be drawn from this rough sketch are that a degree of under-determinacy of language in international law is accepted among the mainstream in critical legal studies thinking but is not seen as the crucial issue. This realm appears to favour more systemic observations, beyond linguistics, and broader claims about the overall operation of international law as a social practice – which, for our purposes, are hard to test experimentally with individuals. This is because experiments such as those in the present study are designed to enable us to examine the cognitive processes of individuals, but the indeterminacy thesis broadly presented under the critical legal studies approach raises no specific claims regarding what international lawyers, as individuals, actually think (for example, when interpreting a treaty). Rather, it focuses on how legal decisions are justified in legal argumentation and is not concerned with how moral convictions bring about such decisions.Footnote 36 Against this backdrop, then, experiments certainly cannot provide evidence supporting broad claims about how international law operates; but they can provide evidence supporting specific aspects of the indeterminacy thesis, namely as to whether morals appear to influence the legal decisions of international lawyers.

2.3 Legal theory and the influence of moral factors on interpretation

As a third approach, we can draw from those theoretical reflections in jurisprudential theory, philosophy, and moral psychology that accept the influence of moral factors on interpretation and discuss its consequences. Such inclusivist theories suggest that this kind of influence is permissible and unavoidable, albeit only under certain circumstances.

To better understand this, we must consider that at least two mainstream, influential, jurisprudential theories, namely, legal interpretivism and inclusive legal positivism, attempt to define what the law is and claim that moral considerations should (normatively speaking) be part of the business of interpretation. As part of the legacy of Ronald Dworkin’s philosophy, broadly, legal interpretivism:

… holds that morality determines how institutional practice affects rights and obligations [and] inherits the holistic structure of morality: the whole of morality confronts the whole of institutional practice and determines its effect, which interpretation purports to identify … moral facts are the grounds of law, but do not directly determine its content. They determine how institutional practice determines the law, i.e., which precise aspect of the practice is a relevant contribution to the law.Footnote 37

Inclusive legal positivism also holds that the rule of recognition, which determines what the law is in a given society, encompasses moral facts.Footnote 38 The debate around interpretivism is concerned with identifying the correct role that moral facts (including institutional practice, if based on these facts) should play in deliberation.Footnote 39

There is consensus that moral considerations should play an important role. However, these should not be born of quick and unreflective impulses based on moral emotions, such as unreflective attributions of blame, but rather all-things-considered conscious decisions.Footnote 40 A similar vein of reasoning inspiring jurisprudential debates can be found in the philosophical, meta-ethical literature on the truth conditions of statements about moral matters. Among others, this literature attempts to answer the following questions: When can we say that a statement about moral matters is true – when most people agree on it or when we have the ‘best’ accessible arguments for it? And what are the ‘best’ arguments? Given the difficulty of answering these questions, a doctrine labelled ‘hybrid expressivism’ was created.Footnote 41 This doctrine is based on the claim that we sometimes simultaneously report our beliefs about non-moral descriptive matters while expressing our attitudes and emotions about moral matters. Those attitudes are conveyed through pragmatic rather than semantic means.Footnote 42

This is because, while the beliefs a person holds and expresses can be either true or false, the matter is rendered more complex when (moral) attitudes are at stake. As fallible humans, our attitudes can always be either wrong (if we believe in moral realism and objective morality) or subjective (if we are relativists about moral matters). If our attitudes are subjective, then there is a risk that we are not grasping the essence of one another’s communications, and thus becoming further-removed from the ‘best’ moral arguments within our society’s reach. Thus, one core idea of hybrid expressivism is that moral views should always be debated, for instance, in the form of ‘meta-linguistic negotiations’.Footnote 43 We should treat the truth conditions of moral statements distinctly and always deliberate as to what is the best solution.Footnote 44

The literature on moral psychology, likewise, shares the concern that our inferring of pragmatic meaning, especially implicatures (as discussed in Section 3), can be distorted by moral emotions such as blame.Footnote 45 Thus, broadly speaking, most lawyers, ethicists, and psychologists would be univocal in the contention that no automatic influence of quick, unreflective moral judgements on truth judgements should be permitted. This claim is vital when interpretive statements about legal rules are at stake. This is because unreflective subjective moral judgements that are not the result of careful deliberation could pose a potential danger to judicial impartiality. Consequently, our experiments inquire into the psychological reality of such truth judgements, for both laypeople and legal experts, to identify the potential risks of human psychology to the virtue of impartiality.

In our experiments concerning the influence of moral factors, we therefore not only test whether elements other than a (self-declared) objective reading of a treaty text by an interpreter play an important, inevitable role in interpretation. We also follow up on two much-debated topics in general legal theory – namely, regarding the existence of quick, unreflective (and, therefore, undesirable) moral judgements and what the occurrence of such judgements would entail.

2.4 The research hypotheses

Most of the claims of the aforementioned doctrines or theories are normative, in that they outline how interpretation should proceed.Footnote 46 In an experimental setting, however, we are enquiring into the descriptive, i.e., how the practice of interpretation is. In other words, to draw conclusions about how interpretation should be, we need to first determine how the psychology of interpretation operates in practice. The premise here is that the normative theory needs to be set within the limits of what people, as interpreters, are actually able to do, and should take into account what they typically do when interpreting. On this basis, we develop three hypotheses that we can test in experiments and that consider both normative and descriptive perspectives.

First, based on the formalist position and given similar circumstances, we should expect certain commonalities between the respective interpretations of a treaty provision by laypersons and experts because of the ordinary-meaning maxim in treaty interpretation. To test this, we apply a typology of interpretation that was developed in the linguistic subfield of pragmatics (on the latter, see Section 3.1). This typology was created for the context of everyday communication; but, given the ordinary-meaning maxim, we should also be able to find it in operation in the context of international treaty interpretation for laypersons and international law experts. The first research hypothesis is therefore:

H1: Assuming a neutral (morally non-valenced) treaty-interpretation scenario, a simplified typology of pragmatic interpretations (explained in Section 3.2 of the present article) is applicable to treaty interpretation in international law by both laypersons and experts.

Second, based on our discussion of the three archetypal (and fundamentally different) perspectives on interpretation outlined above, in a morally-valenced interpretation scenario (i.e., where the interpretive decision that has to be taken includes a decision widely debated as moral in society), we should expect a legal interpreter to automatically (unconsciously) respond in one of two ways: to reject certain influences (such as, in our case, moral considerations) or to be influenced by them. To formulate this in a hypothesis, we will adopt an inclusivist position on interpretation, one that accepts moral factors as an influence and also corresponds largely to the (descriptive, not normative) expectations of a critical legal studies approach. Our second hypothesis is, therefore:

H2: Assuming a morally-valenced treaty-interpretation scenario, legal interpreters (whether laypersons or experts) will be influenced by factors external to the treaty text (in this case, moral factors).

Third, based on the formalist position, we should expect that, if such an effect of moral considerations on interpretation is, indeed observed, legal training should make a difference to the agent’s capacity to reject moral considerations as influences in their interpretations. In other words, legal experts should arguably have been trained to exclude such factors from their interpretive reasoning, in contrast with laypersons, who might be more naturally inclined to be influenced by them.Footnote 47 Our third and final hypothesis is therefore:

H3: Assuming a morally-valenced treaty-interpretation scenario, international law experts are influenced to a lesser degree than laypersons (or not at all) by factors external to the treaty text (in this case, moral factors).

3. The toolkit: Experimental linguistics and pragmatics in legal interpretation

We now turn to the tools we used to test our three experimental hypotheses. Since linguistics remains a relatively unexplored territory among international lawyers, we begin with a primer to define semantics, pragmatics, and experimental linguistics to the extent necessary for the present study. We then turn to Ariel’s theoretical contribution and explain it with the help of non-legal examples.

3.1 Semantics, pragmatics, and experimental linguistics: A primer

We rely here on linguistics to create the scenarios for our experiments, notably semantics and pragmatics as subfields of linguistics. Footnote 48 Both of these subfields are concerned with how to decipher the meanings that are conveyed through language, but they each have a specific focus. On the one hand, semantics deals with how meaning is encoded in the formal components of language. On the other hand, pragmatics examines meaning beyond what is literally said (inferences and interpretations). It is concerned with how context contributes to the meaning of utterances and the communication of concepts or thoughts by means of a particular way of using such components, which contains specific meanings in particular contexts. Footnote 49

Semantics uses a code model, based on the idea that communication is encoded directly or indirectly in language, while pragmatics applies an inferential model, according to which the communicator provides evidence of her/his intention to convey a given meaning. In turn, the audience infers meaning based on the evidence provided, the contextual information, and their prior knowledge. Footnote 50 Take, for example, the utterance ‘Can you pass me the salt?’ Part of the meaning of this utterance (such as the concept conveyed by the word ‘salt’) can be decoded using the code model. Another part of the meaning, however, has to be inferred from the situational context. In this case, we must infer whether the interrogative form is to be interpreted as a request (given that, to comply with standards of politeness, requests are often formulated as questions) or as a literal question about the addressee’s physical ability to pass the salt (if we imagine the interlocutors sitting at a large dinner table with the salt-cellar at some distance from the addressee).

In current linguistics research, scholars – in semantics and pragmatics alike – are increasingly turning to experimental approaches to prove or disprove their theoretical claims.Footnote 51 In a legal context, experimental semantics would, for example, use surveys to examine what respondents consider to fall under a certain notion such as ‘vehicle’.Footnote 52 Experimental pragmatics focuses on proving the empirical reality of categorizations and distinctions developed in pragmatic theory.

Researchers in pragmatics argue that (pragmatic) interpretation in everyday communication follows a consistent set of assumptions, such that we can construct typologies of pragmatic interpretations. In our experiment, we apply one such typology to compare the interpretations made by different individuals and to identify the influence of moral factors in those interpretations. The results of the earlier pilot studies we conducted already appear to suggest that such a typology is valid for application in legal communication (here, the interpretation of treaty norms).Footnote 53

3.2 Ariel’s typology of pragmatic interpretations

In the broader context of everyday language, the linguist Mira Ariel recently presented a comprehensive typology of pragmatic interpretations. We present the core elements of her typology using her everyday-language examples. Based on these types of interpretations, we then construct our scenarios for the experiments.

In her work, Ariel argues – following a pragmatic approach – that understanding a speaker’s communicative intentions requires simultaneous decoding of explicit messages and inferring of implicit messages. The results of this processing of the speaker’s utterance, be it written or spoken – that is, the understandings that derive from it – have a distinct so-called ‘discoursal status’ which varies in terms of prominence. Explicit messages are said to have a more prominent discoursal status than implicit messages,Footnote 54 because their clarity renders it difficult to subsequently refute their meaning. Conversely, in the case of implicit messages (with a lower discoursal status), their inherent subtlety means that certain implicit inferences made by the receiver can be easily ‘cancelled’ by a speaker by simply adding elements that cancel (deny) those interpretations. For example, the speaker in our ‘Can you pass me the salt?’ example could add ‘… that is, “can” in the sense of, “are you able to?”’, which would cancel the possible inference that they are politely requesting that the addressee hand them the salt-cellar. By contrast, it is much more difficult for the speaker to cancel inferences based on explicit elements (for example, it would be hard for the speaker to find a way to prevent the addressee from developing their own interpretation of ‘pass’ in ‘Can you pass me the salt?’).Footnote 55

Cancelability is thus an important benchmark. Cancelability – the extent to which an inference can be readily denied (or not) by the speaker – is a linguistic test to distinguish an implicature (a fallible inference) from a logical entailment (an infallible inference). For example, if one says, ‘A man is mortal’, this logically entails that there exists a man. By contrast, if, upon running out of petrol, a driver says ‘there is a petrol station around the corner’, this merely implies that the petrol station is open. This is because one could always say, ‘there is a petrol station round the corner, but I believe that at this time of day it is closed’. Thus, the implicature ‘the petrol station is open’ is a fallible inference. To measure ‘cancelability’, given that this is a technical notion with a field-specific meaning, psychologists have devised the ‘deniability’ measure.Footnote 56 This is a psychological analogue for the concept of cancelabilityFootnote 57 that can be used in experiments where the sample subjects are laypersons, and, hence, we used ‘deniability’ in our experiments.

Ariel suggests a typology of six very specific types of pragmatic interpretations.Footnote 58 While recent research has shown that this typology can also be applied to case studies of (treaty) interpretation,Footnote 59 this fine-grained distinction is likely to be unwieldy for experimental testing. Following the example of linguists experimenting with this typology,Footnote 60 we therefore rely on a simplified, four-pronged typology derived from Ariel’s model.

The first type is linguistic meaning, a somewhat artificial, yet necessary, type of linguistic meaning. To discern this, the speaker’s intended meaning is made – artificially – as explicit as possible. In our ‘Can you pass me the salt?’ example, the linguistic meaning would be ‘Can you pass me the salt, in the sense of can you physically reach the salt-cellar and give the salt-cellar to me?’.

The usefulness of linguistic meaning becomes clearer when we compare it with the next type: explicature. Explicature designates a type of inference in which an addressee must develop explicit elements of an utterance in order to correctly interpret a speaker’s intended meaning. Ariel uses an example taken from a newspaper article on so-called honour killings to clarify this point: ‘My son said she wasn’t the last one. We’re waiting for the next one.’ In order to make sense, the elements in italics must be developed for interpretation. A resulting explicature could thus be: ‘The speaker’s son said that Busaina Abu Ghanem wasn’t the last female murder victim in the family. He said they were waiting for the next female murder victim in the family.’

Explicature forms part of a single meaning-layer along with the linguistic meaning; pragmatic inferences here are limited to developments of the proposition that is expressed and are not consciously available as separate interpretations.Footnote 61 To verify whether something constitutes an explicature or not, Ariel suggests applying the following ‘that is (to say)’ test: ‘The speaker’s son said that she, that is (to say) Busaina Abu Ghanem, wasn’t the last one, that is (to say) female murder victim in the family.’

The third type of pragmatic interpretation in this simplified typology is strong implicature. Strong implicature designates a type of pragmatic interpretation in which a speaker says one thing (first tier) but intends another (second tier), in that he or she does not express a certain message directly but intends to ultimately supply the interpretation rather than the directly-communicated meaning. In Ariel’s example, during a conversation, someone mentions that a company director (John Doe) has started buying shares in his own company. A lawyer interjects that this constitutes a criminal offence. Another interlocutor (R) suggests that the company director ‘has a mother-in-law’. Ariel applies the following ‘replacement test’ to determine whether the content (meaning) of this utterance gives rise to a strong implicature – that is, whether it actually needs be replaced by an entirely different meaning in order to arrive at the speaker’s intended interpretation. This test shows the message that the last interlocutor, in fact, communicated, thus:Footnote 62 ‘R literally said that John Doe has a mother-in-law, but actually he indirectly conveyed that John Doe would illegally buy shares under his mother-in-law’s name.’ A strong implicature, then, is one that needs to be gleaned (by applying the replacement test, for instance), in order to fathom the message the speaker wants the addressee to derive.

Weak implicature is the fourth type of pragmatic interpretation. This encompasses several phenomena,Footnote 63 but, for our purposes, so-called ‘particularized conversational implicatures’ are the most relevant. Take Ariel’s example (again, from the aforementioned newspaper article on honour killings): ‘Last Saturday night, Busaina Abu Ghanem was murdered, the tenth female victim in the family.’ Here, the intended meaning is not arrived-at by replacing any content. The fact that it is the tenth female murder victim in the family is simply mentioned to deliver something additional beyond the literal meaning of the words and the facts they convey. To make sense of why the speaker chooses to mention this point (given that, beyond being factually true, having ten murder victims in one family is unusual), the addressee will automatically look for an additional meaning layer. For example, Ariel suggests as a possible inference that ‘There is something terribly wrong with this family.’

Particularized conversational implicatures are indirectly-communicated messages in the sense of implied conclusions. They depend on contextual assumptions, but the utterance content (here, ‘the tenth victim’) actively participates in shaping the implied conclusion (‘there is something wrong’).Footnote 64 Such interpretations can be cancelled explicitly and are separate from the relevant explicature – that is, different in content and truth conditions. The implicature might not be true, yet this would have no impact on the truth of the main example (there might, in reality, be nothing ‘wrong’ with the family, even though Busaina Abu Ghanem is, indeed, the tenth female murder victim in that family).Footnote 65 Ariel suggests an ‘indirect-addition’ test to identify such particularized conversational implicatures: ‘The speaker said that last Saturday night, Busaina Abu Ghanem was murdered, the tenth female victim in the family, and in addition she indirectly conveyed that there is something terribly wrong with this family.’Footnote 66

Returning to our study, then, using these four types of pragmatic interpretations – linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature – we constructed four scenarios or vignettes for our experiments.

4. The experiments

Based on our previous discussion of the (simplified, four-pronged) typology of pragmatic interpretations, we set up our experiments through four vignettes (one per type) to test the operation of this typology in both morally-neutral and morally-valenced cases. For this purpose, we drew on a real treaty provision and a real interpretation of the provision by real interpreters of international law to construct a baseline scenario that we then manipulated to introduce moral considerations.

4.1 General design and outcomes of the experiments

4.1.1 The basic scenario

All the participants in our experiments were first asked to read an introductory text that set up the baseline scenario for the experiments:

An international treaty on human rights provides that the Signatory Parties shall guarantee the rights established in the present Treaty. Any restriction of rights has to be justified by an important public purpose and has to be proportionate. The same Treaty also contains the following legal rule … [the relevant experimental vignette then followed]

The purpose of this text was to inform participantsFootnote 67 about the nature, goals, and structure of the treaty. For the lay respondents, this would enable them to make sense of what followed. For the experts, it would situate them in the correct context and enable them to access their relevant expertise (international law, human rights, human rights treaties, for details on expert recruitment see Section 4.1). Moreover, this introductory information was necessary so that all participants could interpret the vignettes according to the ordinary-meaning maxim; as discussed previously, the latter requires that an interpreter must be ‘reasonably informed on the subject matter of the treaty’.Footnote 68 The first of the four vignettes read as follows:

The Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions that will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature. Free elections mean that nationals including women shall be able to vote and run for office unless they spent 15 years or more abroad.

The example is based on Article 3 of Protocol 1 to the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) and relevant jurisprudence by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Article 3 reads:

The High Contracting Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions which will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature.

In the case law, the ECtHR has clarified that it interprets this norm to mean that, although there is a right to vote, this right can be made subject to conditions for nationals and that it can, for example, be lost after fifteen years of residing in another country.Footnote 69 Our first vignette took up this interpretation and made it highly explicit so as to hardly require any interpretive effort at all (linguistic meaning, part in italics above). In the experiment, having read the vignette, all participants were then exposed to the following – consistent – information: ‘Based on this legal rule, an international lawyer draws the conclusion that nationals shall be able to vote and run for office unless they spent 15 years or more abroad.’ We thus asked participants to react to, and evaluate, this interpretation suggested by an international lawyer. They were all shown the exact same international lawyer’s conclusion and had to answer questions on it (either a question on the truth of that conclusion and their confidence in their own assessment of that truth, or a question on the deniability of the lawyer’s conclusion).Footnote 70

Subsequently, the participants had to answer questions on this lawyer’s conclusion to test the ‘gap’ they perceived to exist between that conclusion and the vignette to which they were exposed. In the case of linguistic meaning, of course, this gap was virtually inexistent, whereas it ‘grew’ with every pragmatic interpretation we presented.

To expose participants to a case of explicature, we chose this (second) vignette [italics always omitted]:

The Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions that will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature. This means that all nationals shall be able to vote and run for office without discrimination based on sex or any other impermissible grounds unless they spent a substantial amount of time abroad.

To understand the part of the text in italics and evaluate whether the aforementioned international lawyer’s conclusion could fit as the interpretation of this vignette, in line with Ariel’s methodology, our participants had to develop this explicature:

This means that all nationals shall be able to vote and run for office without discrimination based on sex or any other impermissible grounds unless they spent a substantial amount of time abroad, that is (to say) fifteen years.

To create a situation of strong implicature, our third vignette read as follows:

The Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions that will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature as well as guarantee protection against discrimination and increase the influence of active participants in the country’s civic life.

This time, our participants had to develop the following strong implicature to be able to see the international lawyer’s conclusion as a valid interpretation of the vignette. Note that there was no longer a clearly-determinable part of the text upon which this inference was based; therefore, there were no italics in the third vignette. Our participants had to develop the strong implicature as follows:

The treaty literally stated that the Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions that will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature as well as guarantee protection against discrimination and increase the influence of active participants in the country’s civic life, but actually it indirectly conveyed that nationals shall not be able to vote and run for office if they spent fifteen years abroad.

Our fourth vignette comprised the original ECHR norm in slightly simplified form. The international lawyer’s conclusion now constitutes a particularized conversational implicature:

The treaty stated that parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions that will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature, and in addition it indirectly conveyed that nationals shall not be able to vote and run for office if they spent fifteen years abroad.

The utterance (conditions that will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people) participates in shaping the conclusion (some nationals shall not be able to vote and run for office), but the interpretation is cancellable (the treaty could expressly prohibit residence-based restrictions) and differs in truth conditions (the treaty norm could be true while, at the same time, the conclusion drawn could be false).

The data gathered in this stage of the research indicated the extent to which people agreed with the lawyer’s interpretation. According to H1, based on the ordinary-meaning maxim, we expected to see the different discoursal statuses of the types of pragmatic interpretations reflected in the overall results of both laypersons and experts. That is, we broadly anticipated that the typology would basically be visible in the results for both groups. However, it could be possible for differences in interpretive behaviour between experts and laypersons to emerge. For instance, perhaps there would be less willingness to accept a more far-fetched interpretation (that is, one with a weaker discoursal status) among the experts in the sample, all of whom were schooled in the interpretative methods of international law.

4.1.2 Adding morals

In a second step, we manipulated our vignettes by introducing moral considerations. We took care to change the phrasing as little as possible, to minimize the potential introduction of other factors that could affect the results, such as semantic differences leading to different quantification inferences etc. Nonetheless, in each case, we made a modification with very clearly moral connotations.

In all cases, we relied on the exact same four international law vignettes, except that we substituted the word ‘women’ for the word ‘nationals’ and removed the condition of fifteen years of residence abroad in the conclusion of the international lawyer presented to the participants (and in the questions they subsequently had to answer). To select our morally-valenced scenario within an international law context, we turned to the ECtHR’s case law. The ECHR prescribes that women cannot be excluded from the right to vote or to stand for election. In one decision, for example, the Court declared inadmissible an application from a highly traditional Protestant party complaining about an obligation to open its lists of candidates to women. The Court held that the progress toward gender equality precluded an ECHR member state from supporting the idea that a woman’s role was secondary to that of a man.Footnote 71 We take this to be evidence of an overall development in moral standards that indicates that most people today find the exclusion of women from political rights to be morally unacceptable.Footnote 72

In the case of nationals being excluded from the right to vote after a period of non-residence in the relevant country, we expected the participants in our experiment to hold various moral views but no particularly strong conviction as to whether such a rule is morally right or wrong. By contrast, we considered that the vast majority of the participants – both experts and laypersons – would share a strong moral conviction that there should be no discrimination on the grounds of gender with regard to the right to vote or stand for elections.Footnote 73

On this basis, these small changes to the experimental design were intended to ensure that we could identify the relevance of moral factors in interpretation and readily compare the results of the two different scenarios without having to take into account additional changes to the experimental design that could produce unwanted ‘noise’. We asked all participants to answer a final control question on the moral valence of the scenario in each experiment, to verify the moral valence of our approach.Footnote 74

4.1.3 Limitations of the research design

Certain limitations of the chosen research design should be openly addressed. As one first important caveat, the vignettes to which all participants were exposed were, of course, rather simple compared to a real-life situation of interpretation in international law. They contained only the basic elements necessary for interpretation: the text itself (modelled closely on actual international legal treaty texts, based on actual results of real-life interpretive exercises in the interpretations to be judged); some context (that we are dealing with an international human rights treaty with a structure typically familiar to international lawyers, namely, containing the possibility of restricting rights for important public purposes and the need for proportionality); and some elements of the object and purpose of the treaty (a treaty on human rights that the parties have to guarantee). In real life, there would be more (and perhaps more complex) elements – the full text of that human rights treaty, in particular. We tolerated this incompleteness as inevitable in order to be able to present the same vignettes to laypersons and international lawyers, as the former could otherwise be overwhelmed by the ensuing complexity of the vignette and potentially unable to complete the task. That said, our results indicate that the differences in the cognitive environment of participants – experts relying on their international law knowledge vs. laypersons relying on their intuition and world knowledge – do not seem to have played a significant role.

Second, another element we could not fully reproduce was that of the conditions and stakes of a real-life human rights court scenario in which much might depend on a particular interpretation of a treaty provision. We could avoid the external validity concern of having a convenience sample by relying both on experts and on randomly selected laypersons.Footnote 75 However, we could neither fully reproduce a collective decision-making situationFootnote 76 nor the stakes of judicial decision-making and interpretation in a human rights context. As all of this cannot be realistically recreated in an experimental setting, we did not attempt to do so (e.g., by putting participants in groups or by describing a real case that would be decided one way or another based on the chosen interpretation). Instead, we asked laypersons and experts to judge somebody else’s interpretation. Additionally, our experiments were online surveys and thus lacked the immersive setting of a lab experiment. However, the online form permitted us to gain more than to lose – the online form permits to obtain a sample size which guarantees that the results are robust – they will replicate (be the same in terms of statistical significance) if the experiment is carried out again on a different, though equal in size, sample. In other words, the lab setting does not permit to ask questions to hundreds of participants at once.

Third, to mitigate the effect of the authority that a judgment of an international court might have, in particular, for laypersons, we chose the notion of a ‘conclusion’ drawn by an ‘international lawyer’ so as not to create a sense of legal authority or superiority that might unduly influence laypersons (they would arguably find it easier to contradict an ‘international lawyer’ than an ‘international judge’ or a ‘member of an international court’). Also, this non-authoritative phrasing was chosen to incite both laypersons and experts to question whether they agreed with the international lawyer’s ‘conclusion’ (rather than using language such as a ‘decision’ by an international court). For experts, this would help them feel licensed to scrutinize a decision taken by a perceived ‘peer’, from the perspective of their expertise. Some feedback we received by email from expert participants after they had responded to the survey seems to indicate that they did exactly that; they reflected not only upon the notion of deniability of the international lawyer’s conclusion but also on the similar, yet different, conclusions drawn by the international lawyer in the different vignettes to which they were exposed. All in all, we opted for an approach that studied the micro-foundations (i.e., the legal interpreter’s mind) of macro-level problems of decision-making.Footnote 77

Fourth, a further potential limitation of our research design that must be acknowledged is its focus on the English-speaking ‘Western’ world. Our studies were performed in the English language with the participation of laypeople and experts mostly from the Western cultural area. This was due to practical reasons, primarily the need to recruit a sufficient number of lay participants to our online experiments within a reasonable period and the difficulty of contacting international law experts and securing their agreement to participate. In the latter case, we had to resort to directly contacting persons who were familiar to us and, thus, typically based in similarly ‘Western’ institutions, or recruiting via international law blogs usually read by a particular set of international lawyers working in English. This could arguably restrict or skew our results to a Western cultural perspective. We disagree with such an assessment, however, for two reasons.

On the one hand, the original study that inspired our design, namely, that of Sternau et al.,Footnote 78 was carried out in Hebrew and we replicated it in the English language.Footnote 79 The results were robust and similar. This gives us preliminary grounds for thinking that our results are cross-linguistically stable and independent of the particular semantic structure of one specific language. On the other hand, there exists a large body of literature in the field of intercultural pragmatics that holds that the patterns of pragmatic inference are identifiable and robust in most human languages.Footnote 80

A final limitation is that we phrased the questions in the experimental vignettes using the form ‘you’.Footnote 81 This could, at least theoretically, trigger an unwanted influence in the sense that participants as addressees could feel personally involved to a greater extent than desirable.Footnote 82 Future experiments could thus use an impersonal style of questioning to avoid this potential drawback.Footnote 83

With these limitations taken into account, we now describe the concrete set-up of each experiment and its outcomes. The overviews that follow only set out the results of the experiments in abbreviated form, relegating many technical details to the Annex. We then provide an overall discussion of the results, including certain caveats that are due to the aforementioned inevitable limitations of our research design.

4.1.4 The first experiment (1a): Testing lay intuitions in morally-neutral cases

For Experiment 1a, we recruited lay participants (there was a control question at the end of the survey, concerning participants’ lack of legal expertise) for an online survey that we created on the Qualtrics platform via a link on the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform. The platform distributed the survey to 800 potential participants, and the IP address location was restricted to the United States. Participants who failed the attention check, who were not native speakers of English, or who completed the survey too quickly (in less than one minute) were excluded, leaving a final sample of 708 participants (57 per cent of participants were female; mean age was 40 years, standard deviation: 13 years, age range: 18–90 years).Footnote 84 No participant could take the survey twice.

Eight groups were formed. Each group was randomly assigned to one of the eight slightly modified versions of the same survey, based on the four formulations of the legal rule (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, weak implicature) and two different sets of questions (truth and confidence vs. only deniability). This meant that each participant saw the exact same international lawyer’s conclusion and always responded to questions precisely on this same lawyer’s conclusion – as noted earlier, either questions about the perceived truth of that conclusion and confidence in the assessment (judgement) of that truth; or a question on the conclusion’s deniability. All answers were measured on 7-point Likert scales except for truth, which was a binary measure (possible answers: true or false). The questions on truth and confidence were the following: ‘[truth]: Based on the text you have read, do you think that the last sentence is true/false? … [confidence]: How confident are you in your answer? (1= not at all confident; 7 = fully confident)’.

Alternatively, participants responded to a question on cancellability (expressed as deniability):

[deniability]: To what extent will the lawyer be warranted in saying in the future: ‘In that situation, I did not say that nationals shall be able to vote and run for office unless they spent 15 years or more abroad’? (1 = completely unwarranted; 7 = completely warranted)

All participants answered a final control question on the moral valence of the scenario:

[morals]: How do you assess morally the lawyer’s conclusion that ‘nationals shall be able to vote and run for office unless they spent 15 years or more abroad’? (1 = morally bad; 4 = neither morally good nor bad; 7 = morally good)

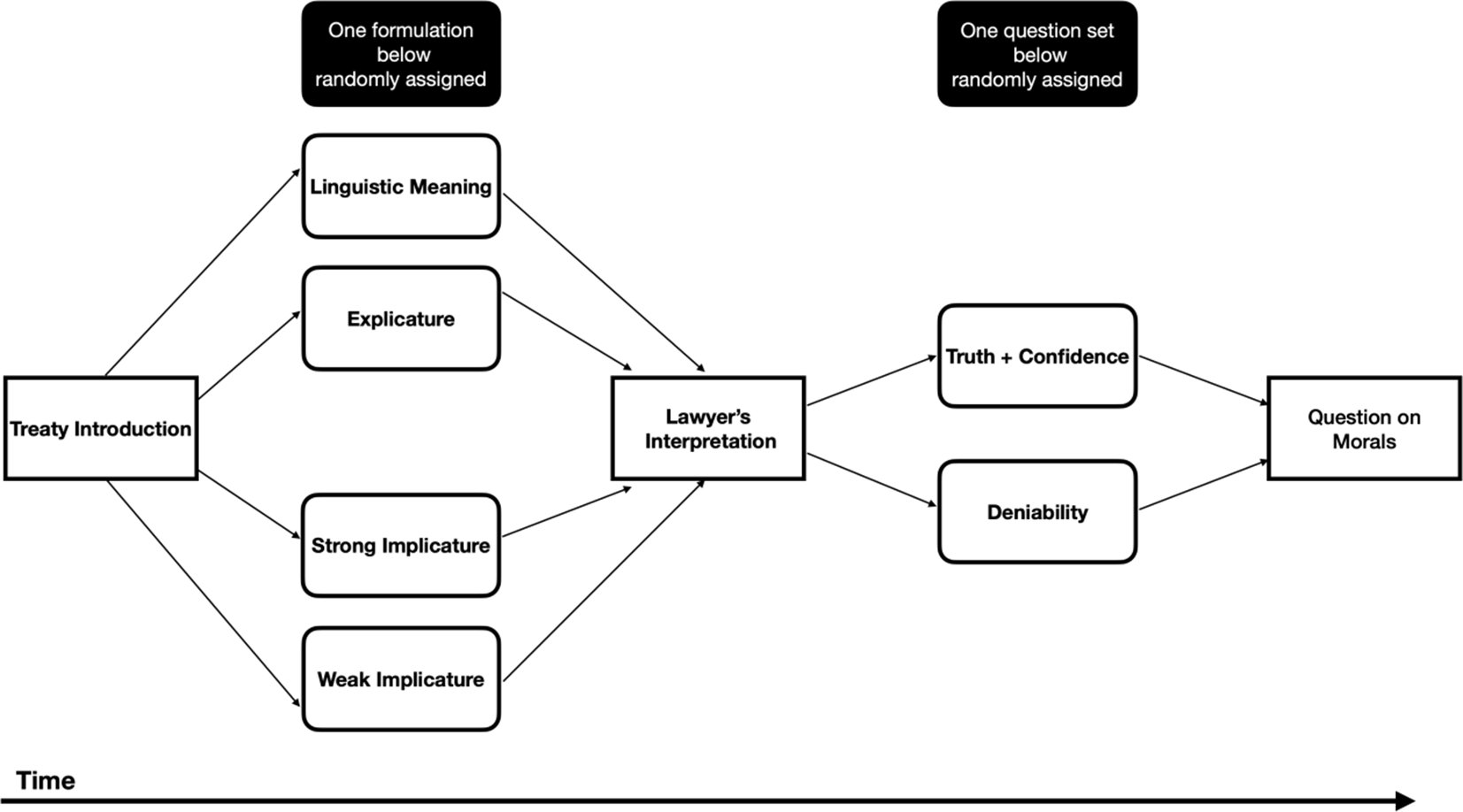

The survey design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Experimental design for experiment 1a.

As expected under the pragmatic typology and H1, the results show that the percentage of participants who agreed with the lawyer’s conclusion decreased in line with the decreasing level of explicitness of the legal rule. In other words, the more the lawyer’s conclusion explicitly matched the wording of the legal rule, the more participants judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true. We did expect to find a slightly more pronounced difference between reactions to the strong and weak implicature vignettes; however, the type of formulation of the legal rule did have a clear influence on the responses. Footnote 85

As the pragmatic typology would predict, the reaction times increased in line with a decreasing level of explicitness of the legal rule. Hence, if the lawyer’s interpretive conclusion departed from the wording of the rule, inference time naturally increased, with the exception of weak implicature. Interestingly, participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true reported a decreasing confidence in their judgements in line with decreasing levels of explicitness of the legal rule. In other words, the less explicit the legal rule on which the lawyer’s conclusion was based, the less confident the participants were about their truth judgements of that conclusion. By contrast, changing the formulation of the legal rule did not impact participants’ assessment of how deniable the lawyer’s conclusion was. Footnote 86

Summing up this experiment, the level of explicitness of a legal rule did influence truth judgements and confidence about truth judgements about the lawyer’s interpretive conclusion (higher for higher levels of explicitness). However, the level of explicitness did not influence judgements of how deniable the lawyer’s conclusion was (participants did not judge conclusions to be less deniable despite higher levels of explicitness). The gender of the participant was found to exert no effect on truth judgements, so we collapsed across this factor in the analyses.Footnote 87 In the second experiment, we contrasted these results (from a morally-neutral scenario) with a morally-non-neutral scenario to check whether our results were robust, independent of the moral valence or absence thereof.

4.1.5 The second experiment (1b): Testing lay intuitions in morally-non-neutral cases

Using the same approach as described for Experiment 1a, 724 participants (female: 59 per cent; mean age: 40 years, standard deviation: 13 years, age range: 18–95 years) successfully completed the survey, this time using the ‘women’ condition instead of the ‘nationals’ condition in the international lawyer’s conclusion and the questions asked of the participants. Strikingly, contrary to the results from the previous experiment and regardless of the level of explicitness of the legal rule, the percentage of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true was descriptively stable. The reaction times were also similar for each formulation.

Again, the formulation of the legal rule exerted an influence on confidence about truth judgements. However, this influence was weaker than in the case of Experiment 1a, the differences in means being less pronounced. Formulation had no influence on deniability judgements. Footnote 88 Again, as gender had no effect on truth judgements, we collapsed across this factor in the analyses.Footnote 89

The results show that the level of explicitness of a legal rule relative to the lawyer’s interpretation influenced participants’ truth judgements to a much lesser extent than in Experiment 1a. By contrast, it did influence confidence about truth judgements (higher for higher levels of explicitness), but the level of explicitness did not influence deniability judgements (these were not lower for higher levels of explicitness).

GIf we compare Experiments 1a and 1b on the basis of these initial results, we can observe that the moral valence of the scenario had a statistically-pronounced influence on the responses. On a 7-point Likert scale, where 4 was the neutral mid-point, the mean responses to the question regarding a moral assessment of the lawyer’s conclusion were M=4.27, with a standard deviation of 1.47, in the morally-neutral scenario, and M=5.91 (with a standard deviation of 1.42) in the morally-valenced scenario. These scores were significantly different (cf. Annex Section 6.A.2). This indicates that our manipulation of the moral valence of the scenario worked as predicted: the ‘women’ condition was perceived as morally-non-neutral, and the ‘nationals’ condition as morally neutral.

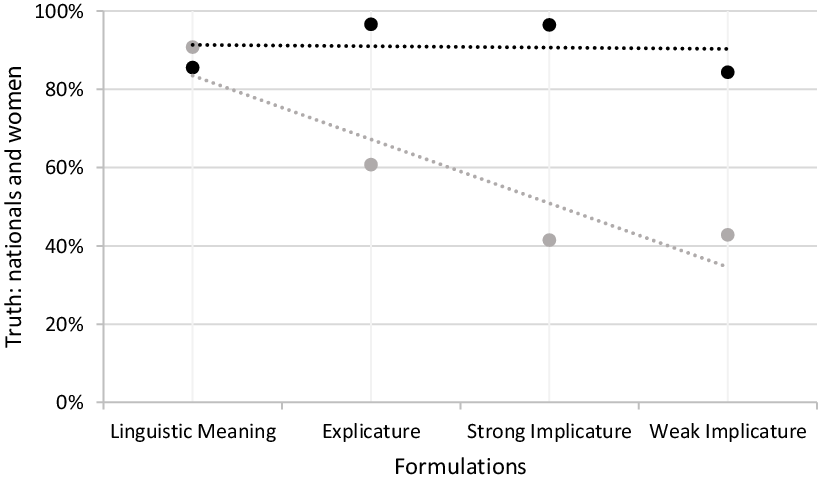

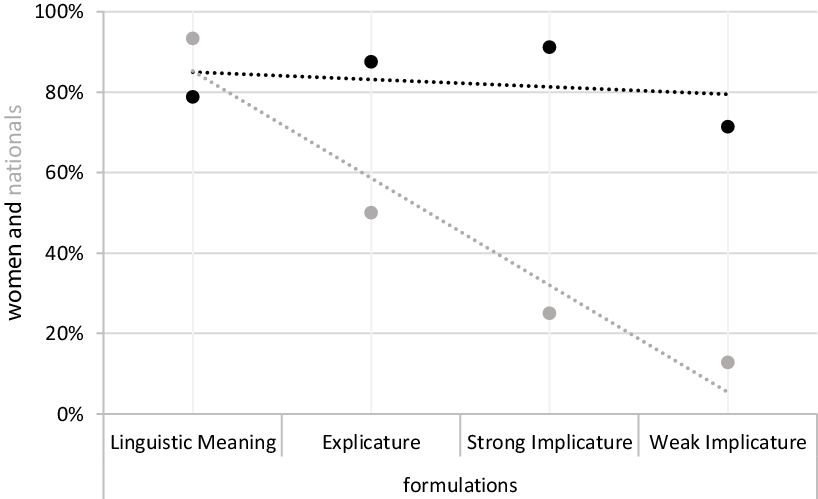

In the moral condition (employing the word ‘women’), most participants deemed the lawyer’s conclusion to be true for all formulations. By contrast, in the non-moral condition (employing the word ‘nationals’), there was a decreasing number of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true, in line with a decreasing level of explicitness (cf. Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2. Percentage of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally-non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) conditions.

Table 1. Percentage of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally-non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) conditions

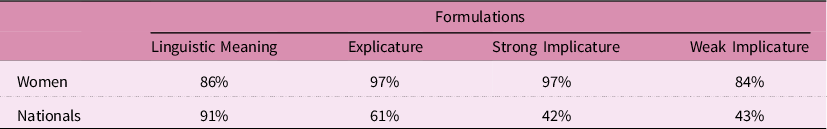

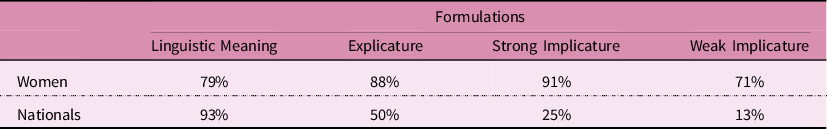

The confidence about truth ratings was lower for each of the formulations in the neutral compared to the non-neutral scenario (cf. Figure 3). This means that participants were more confident about interpretations that conformed to their moral views, even if those interpretations largely departed from the explicit text of the interpreted legal rule. The same participants judged interpretations that conformed to their moral views to be true, even if those interpretations largely departed from the explicit text of the interpreted legal rule.

Figure 3. Mean ratings for confidence in truth judgements for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally-non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) conditions.

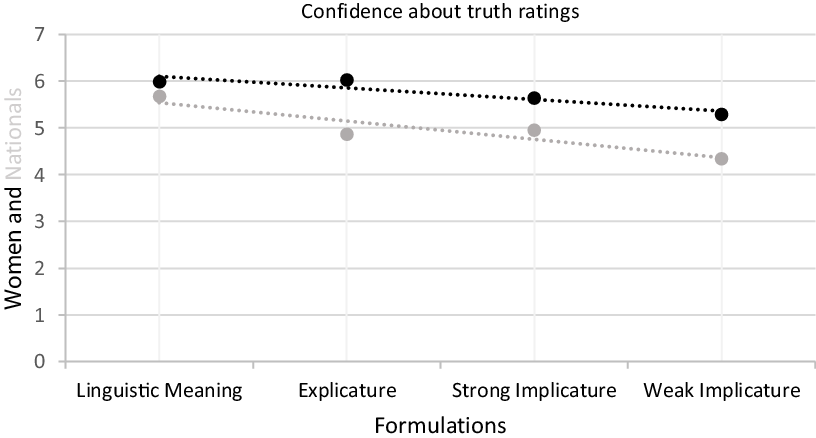

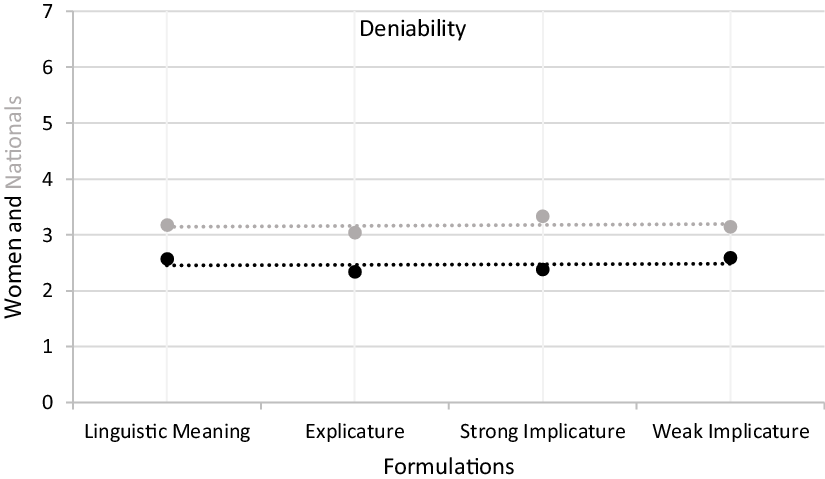

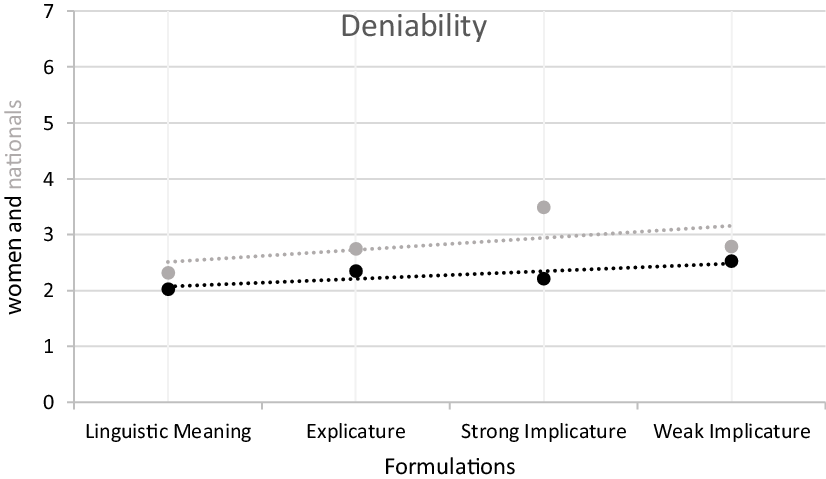

With regard to the mean responses to the question of how deniable the lawyer’s conclusion was, deniability in the morally-non-neutral scenario was lower for every formulation of the legal rule, compared to in the neutral scenario (cf. Figure 4). This suggests that it is more difficult to deny an interpretation of a legal rule that conforms to one’s own moral conviction than it is to deny a morally-neutral interpretation. It also indicates that, if the interpretive conclusion is in accordance with one’s moral convictions, then it can deviate much more from the explicit written text of the interpreted legal rule at stake and still be accepted.

Figure 4. Mean ratings for deniability for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally-non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) conditions.

As predicted in H2, the level of moral endorsement of pragmatically-conveyed content influenced participants’ truth judgements of the international lawyer’s interpretation. In the morally-neutral scenario, the percentage of all participants judging the lawyer’s conclusion to be true decreased in line with the decreasing level of explicitness of the legal rule. By contrast, in the morally-non-neutral scenario, a roughly equal percentage of participants judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true across all four levels of explicitness of the legal rule (linguistic meaning vs. explicature vs. strong implicature vs. weak implicature). The decrease in confidence in truth judgements in line with decreasing levels of explicitness was somewhat sharper in the morally-neutral scenario. Finally, the level of deniability of the lawyer’s conclusion was stable for all levels of explicitness of the legal rule in both scenarios, but the level of deniability was significantly lower in the morally-non-neutral than in the morally-neutral scenario.

We can thus conclude that, in the case of laypersons, moral valence has a strong influence on truth judgements and the processing of the pragmatic content of an utterance. As discussed in Section 2.3, this is in line with meta-ethical theories such as hybrid expressivism.Footnote 90

4.1.6 The third experiment (2a): Testing expert intuitions in morally-neutral cases

For Experiments 2a and 2b, 321 participants were recruited online in their capacity as international law experts, via international law blogs (EJIL:Talk! and Völkerrechtsblog) as well as personalized email invitations. Participants who failed the attention check,Footnote 91 took less than a minute to complete the survey, or had no legal background were excluded, leaving a final sample of 166 participants (female: 34 per cent; mean age: 35 years; standard deviation = 10 years; age range: 20–67 years).

For ease of presentation, we first describe the data for the morally-neutral version of the scenario (Experiment 2a) and then the data for the morally-valenced scenario (Experiment 2b). However, data for both experiments were collected in a single, joint batch. This is because experts in international law are scarce and we were unable to gather the full sample recommended by a predictive power analysis (around 1,600 participants); instead, we employed a per-trial statistic. This means that each participant was assigned to four (rather than to just one) of the 16 conditions. All materials were exactly the same as in Experiments 1a and 1b.

In line with the results from Experiment 1a, and as predicted in H1, the results of experiment 2a show that the percentage of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true was highest in the group presented with the linguistic meaning of the legal rule. This percentage significantly decreased in line with a decreasing literalness of the lawyer’s interpretation compared to the legal rule. The reaction times were similar.

Contrary to Experiment 1a, there was no significant difference between confidence in truth judgements. In other words, participants judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true with a comparable degree of confidence for each of the formulations of the legal rule. However, we must stress that, in the present experiment, the differences in the percentages of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true were significant for each formulation – even strong and weak implicature – which was not the case in Experiment 1a. There was also a significant difference in confidence judgements between linguistic meaning and explicature conditions. This allows us to maintain the firm conclusion that the level of explicitness of the legal rule has a strong influence on truth judgements of interpretive statements and that the pragmatic typology is applicable to the legal realm (equally, when interpretation is performed by legal experts, as per H1). Just as in previous experiments, deniability judgements were stable across different groups. All in all, experts’ responses were similar to laypeople’s in the morally-neutral scenario.

4.1.7 The fourth experiment (2b): Testing expert intuitions in morally-non-neutral cases

In line with the results of Experiment 1b, like the lay participants, experts judged the lawyer’s interpretive conclusion to be true, regardless of the formulation of the legal rule. Reaction times increased in line with a decreasing level of explicitness of the legal rule on which the lawyer’s interpretation was made, with the exception of the weak-implicature condition. The responses to the remaining questions were also very similar regardless of which version of the legal rule was presented to participants. Again, legal experts’ responses were very similar to those of the lay participants.

If we compare the results of Experiments 2a and 2b, the moral valence of the scenario influenced expert judgements just as it influenced lay judgements. On a 7-point Likert scale where 4 was the neutral mid-point, the mean responses to the question of how to morally assess the lawyer’s conclusion were M=3.77 (with a standard deviation of 1.34) in the non-moral scenario and M=5.65 (with a standard deviation of 1.53) in the moral scenario. The difference was statistically significant (cf. Annex, Section 6.B.2). This means that our manipulation of the moral valence of the scenario worked as predicted with the experts as well as with the laypersons.

In the morally-non-neutral scenario (employing the word ‘women’), most participants deemed the lawyer’s conclusion to be true for all formulations. The trend was different for those who were presented with the morally-neutral condition (employing the word ‘nationals’). In the latter case, there was a decreasing number of participants that judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true in line with a decreasing level of explicitness of the legal rule compared to its interpretation (cf. Figure 5 and Table 2). This indicates that, if an interpretation conforms to one’s moral views, then one confidently judges that interpretation to be true, even if it bears little resemblance to the explicit text of the legal rule being interpreted.

Figure 5. Percentage of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally-non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) conditions.

Table 2. Percentage of participants who judged the lawyer’s conclusion to be true for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally-non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) conditions

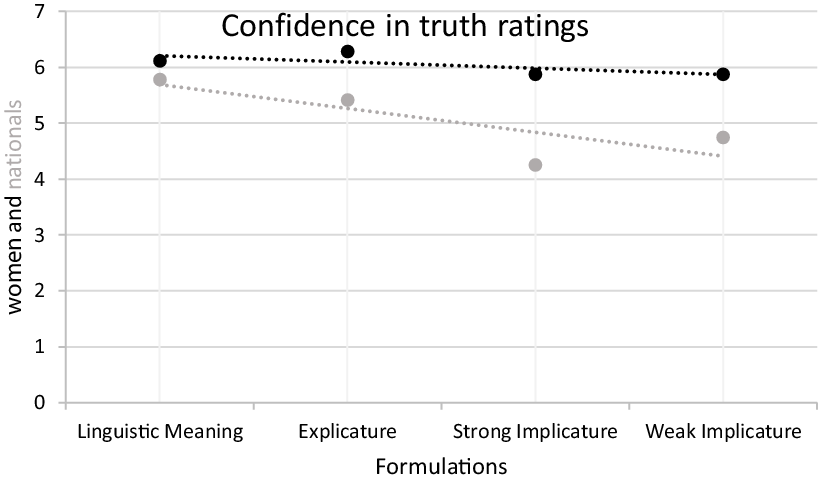

In the morally-non-neutral scenario, the experts’ level of confidence in their truth judgements was higher compared to the morally-neutral scenario, regardless of which version of the legal rule was presented to them (cf. Figure 6).

Figure 6. Mean ratings for confidence in truth judgements for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally-non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) scenarios.

The mean responses to the question of how deniable the lawyer’s conclusion was show that, if an interpretation conforms to one’s own moral views, then one is unwilling to deny that interpretation, even if it bears little resemblance to the explicit text of the legal rule being interpreted (cf. Figure 7).

Figure 7. Mean ratings for deniability for all four formulations (linguistic meaning, explicature, strong implicature, and weak implicature) in the morally non-neutral (‘women’) and morally-neutral (‘nationals’) conditions.

All in all, as predicted in H2, the level of moral endorsement of pragmatically-conveyed content influenced truth judgements. In the morally-neutral scenario, the percentage of expert participants judging the lawyer’s conclusion to be true decreased in line with the decreasing level of explicitness of the interpreted legal rule. By contrast, in the morally-non-neutral scenario, a roughly equal percentage of participants judged the conclusion to be true across all four levels of explicitness. The decrease in confidence in truth judgements vis-à-vis decreasing levels of explicitness was somewhat sharper under the morally-neutral condition. Finally, the level of deniability of the lawyer’s conclusion was stable for all levels of explicitness in both scenarios. However, the level of deniability of the lawyer’s conclusion was significantly lower in the morally-non-neutral scenario than in the morally-neutral scenario.

Thus, we can infer that moral valence has a strong influence on truth judgements and the processing of the pragmatic content of an utterance, both for laypeople and for legal experts in international law. Again, we find this result to be in line with meta-ethical theories, such as hybrid expressivism.Footnote 92

4.1.8 The fifth experiment (3): Testing laypersons’ intuitions in morally-non-neutral cases

Thus far, our research design focused on the impact of moral factors on interpretation, relying exclusively on expected positive moral views on a particular interpretation. We did not undertake tests based on a conclusion drawn by the international lawyer toward which we would expect participants to have a morally-negative view (e.g., an interpretation problematically excluding certain reprehensible behaviour from the scope of an international criminal law prohibition). On that basis, we discovered that – to a certain extent – international lawyers are quick to agree with interpretations that echo their own moral values. Nonetheless, in the present experiment, we needed to test whether morally-negative views exerted an adverse effect on interpretation in a relevant scenario.

We therefore performed an additional experiment among lay participants only, to test whether a morally-bad interpretation would be assessed differently than the morally-good and morally-neutral interpretations tested in Experiments 1a and 1b. We recruited 800 participants through the exact same procedure used for the previous experiments. We also used the same experimental design but modified the legal rules and the lawyer’s conclusion so as to suggest that both supported the exclusion of women from voting rights (for details, cf. Annex Section 6.C.1).

We found that, for these lay participants, moral reasoning exerted an influence on pragmatic reasoning. However, this influence differed depending on whether people found the interpretive statement morally good or bad. If participants found the statement morally good, then they judged the statement to be true, irrespective of the explicitness of the legal rule on which the statement was based. By contrast, if participants found the statement to be morally bad, then they very rarely found it true. If the statement contradicted an explicit legal rule, then slightly more participants found it false than when the legal rule was less explicit regarding the controversial matter. Overall, we can conclude that moral reasoning plays a greater role in processing morally-good interpretations than in processing morally-bad ones. We must, however, be cautious about making any generalizations about our results as we could only collect data on this issue for a sample of lay people (not international law experts), due to resource limitations.

4.2 General discussion

To summarize our findings, our first hypothesis was that the simplified typology of pragmatic interpretations should be considered universal to human communication and thus also apply in a legal context (here, international treaty interpretation). This has – againFootnote 93 – proven to be the case, as we could identify the various types of interpretation both in the experiments with laypersons and with experts. Our second hypothesis – based on our adoption of an inclusivist (and, to a certain extent, a critical legal studies) positionFootnote 94 – was that moral factors influence interpretation in international law. The experiments have shown, in perhaps the most surprising takeaway of all, that this was not only the case for laypersons but also (and to practically the same extent) for international law experts. This stands in contrast with our third hypothesis – that legal training should make a difference in the influence of moral considerations on interpretation – which did not find empirical support. Our final experiment nuances this finding, however, as it appears that moral considerations have a stronger impact when interpreters have to quickly process interpretations that they consider morally good compared to those they consider morally bad. What does this mean overall and what conclusions are we licensed to draw from these findings?

4.2.1 First conclusion: Linguistically, international lawyers are humans, too

A first conclusion we can draw from our study is that, not only does the typology of pragmatic interpretations we have relied upon seem to have worked but also that it provides us with additional insights on ordinary meaning in treaty interpretation in international law. A much-debated topic, the notion of ordinary meaning has recently been criticized as being fundamentally underdefined in several respects, notably with regard to whose ordinary meaning is at issue.Footnote 95 While we cannot resolve this question here, and the general definitions given in the literature are not of much help,Footnote 96 our results hint at how to perhaps refine the thinking around this notion. As Sternau et al. have argued,Footnote 97 typologies of pragmatic meaning proposed by theorists such as Mira Ariel are not just theoretical postulations but a psychological reality. In everyday, casual conversational contexts, interlocutors distinguish between linguistic meaning, explicature, and implicature. These authors have also demonstrated that the difference can be captured in terms of reaction times, judgements on whether utterances are true, confidence in those truth judgements, and judgements on whether a statement is deniable. Moreover, Sternau et al.’s study is not the only one to confirm the psychological reality of the pragmatic typology; in fact, the entire field of experimental pragmatics constitutes a step in this direction.Footnote 98