Introduction

Research into the development of Bronze Age societies in Europe and the Mediterranean has emphasized the importance of trade associated with the development of metallurgy (e.g. Childe, Reference Childe1958; Briard, Reference Briard1997; Kristiansen & Larsson, Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005; Earle et al., Reference Earle, Ling, Uhnér, Stos-Gale and Melheim2015). The presence of a wide range of copper and bronze artefacts, particularly weapons, in the archaeological record has reinforced the image of the Bronze Age as the period in which warrior elites emerged and social stratification began (e.g. Gilman, Reference Gilman1981; Lull, Reference Lull1983; Chapman, Reference Chapman1991; Harding, Reference Harding2000).

This perspective has, however, led to a certain undervaluing of the importance of other crafts in the processes of social development, including, in our opinion, textile production. Indeed, textile production—especially weaving and sewing—requires great skill and ability, as well as many hours of work. Such attributes are usually associated with craft specialization and the technical division of labour.

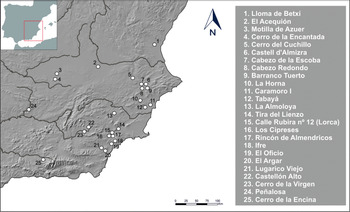

While studies carried out in the Eastern Mediterranean and elsewhere in Europe have highlighted the economic and social importance of textiles (e.g. Lucas & Harris, Reference Lucas and Harris1962; Barber, Reference Barber1991; McCorriston, Reference McCorriston1997; Killen, Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007; Gleba, Reference Gleba2008; Harris, Reference Harris2012; Andersson Strand & Nosch, Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015; Frei et al., Reference Frei, Mannering, Vanden Berghe and Kristiansen2017; Bender Jørgensen et al., Reference Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Stig Sørensen2018; Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Earle and Cardarelli2018; Sabatini & Bergerbrant, Reference Sabatini and Bergerbrant2019), textiles have been undervalued and gone almost unnoticed on the Iberian Peninsula. Research conducted in its south-eastern part has identified three cultural groups in the region: El Argar, the Valencian Bronze Age culture and the Motillas or La Mancha culture (Figure 1). All developed between 2200 and 1500 cal bc, with a diversity of occupation sequences, and with different degrees of social development observable in differences in the structure of settlements, demographic concentrations, and social practices. Among them, the best known is El Argar (Siret & Siret, Reference Siret and Siret1890; Lull, Reference Lull1983; Chapman, Reference Chapman1991; Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete, Risch, Hernández, Soler and López2009; Aranda et al., Reference Aranda, Montón-Subias and Sánchez Romero2015) thanks to the long research history and the large quantity and high quality of the excavations and studies undertaken there. The aim of this article is to evaluate the archaeological evidence for textile production and its importance in Bronze Age societies in the eastern Iberian Peninsula.

Figure 1. Distribution of Bronze Age archaeological cultures of the eastern Iberian Peninsula.

Theoretical Considerations

Activities related to textile production in the Iberian Peninsula have not usually been taken into consideration in the discourse to explain the emergence of processes of specialization and the social division of labour, or the development of social hierarchies. We believe that it has been underestimated for a variety of reasons, including the scarcity of textile evidence preserved in the archaeological record and because textile production, particularly spinning and weaving, has been considered a female and therefore a domestic activity based on ethnographic and ancient iconographic sources.

The nature of textile production, however, implies the participation of a large number of people involved in the multiple tasks associated with obtaining wool, flax, and other plant fibres, their processing and treatment, and the production of a wide variety of products. In addition, this is an activity that requires a large and varied number of tools, from awls and bone or metal needles to clay spindle whorls and loom weights, and wooden warp-weighted looms. Their manufacture would in turn have required the participation of numerous craftspeople (Costin, Reference Costin, Maschner and Chippindale2005, Reference Costin and Bolger2013). The labour and collaboration required for these processes would have needed efficient coordination and planning by at least part of the community or group.

If these activities were undertaken within a household, extended family group, or lineage, the aim would have been to meet the needs of all the members of the group, with any surplus used in exchange for other goods. If, on the other hand, it was organized within an early class-based society, both the raw materials, whether processed or not, and the textiles or even the finished garments, could have served as tribute (Killen, Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007; Algaze, Reference Algaze2008).

Textile production, therefore, does not appear to have been an activity of little importance. On the contrary, it brings together a series of processes, sequentially linked, including those that cover basic needs but which also go beyond merely providing clothing. Clothing, but also insignia such as pennants, are elements of group identification as well as supports for ideological and symbolic meanings; and they continue to be used in present-day societies as elements of group or community expression (Bender Jørgensen et al., Reference Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Stig Sørensen2018). To produce textiles involves a wide range of activities: cultivation, animal husbandry, the collection of wild resources, and crafting (Gleba, Reference Gleba2008; Gleba & Mannering, Reference Gleba and Mannering2012; Costin, Reference Costin and Bolger2013; Andersson Strand & Nosch, Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015). These tasks require specific spaces for the storage of raw materials, as well as their treatment and manufacture (Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013). Therefore, textile production entails a complex chain of processes which are connected spatially, temporally, and technologically. This requires careful planning and organization, from producing and managing the raw materials, to making the yarn, and the final processes of preparing the fabrics, fashioning, and sewing the garments (Costin, Reference Costin and Bolger2013). Textiles would, therefore, have been high-value goods (Risch, Reference Risch2002), especially considering the time invested in their preparation. Moreover, they could acquire an exchange value, given their social role, in addition to their durability, quality, and ease of storage and transport.

Among the eastern Iberian Bronze Age societies, and particularly the Argaric culture, there are various considerations to address, including to what extent the production, exchange, and distribution of textiles may have been under the control of an incipient elite and how forms of appropriation of such goods may have been carried out within domestic groups.

Evidence of Textile Production

Currently, there are more than a hundred sets of archaeological records associated with textile production, which can be grouped in two categories. The first encompasses funerary contexts, where the remains of linen fabrics used as shrouds or to wrap metal objects deposited as grave goods have been found (Alfaro, Reference Alfaro1984, Reference Alfaro, Gleba and Mannering2012; Hundt, Reference Hundt, Schubart and Ulreich1991). The second category includes the household spaces within settlements, with evidence of implements associated with textile production, such as loom weights, spindle whorls, thread coils, spools, spacers, and awls. Further evidence includes the remains of flax stems and seeds, and the charred remains of other species, found on the floor of burned houses (Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013).

Funerary Contexts

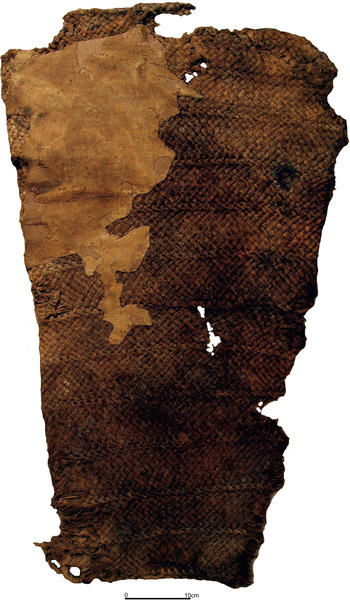

Almost all the garments and fabric fragments recorded in the Iberian Peninsula are made of linen (flax). One exception is the possible wool cap and woven esparto grass leggings found in Grave 121 at the El Argar-culture site of Castellón Alto in the province of Granada dated between 1800 and 1600 cal bc. Here, a carbonized material was also found, perhaps the residue from the burning of a skein of wool (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Rodríguez, Cámara and Moreno2000: 89; Molina et al., Reference Molina, Rodríguez-Ariza, Jiménez-Brobeil and Botella2003; Rodríguez-Ariza & Guillén, Reference Rodríguez-Ariza and Guillén2007: 67). These rare finds contrast with almost one hundred recorded fragments of linen garments, shrouds, or sheets (Siret & Siret, Reference Siret and Siret1890; Alfaro, Reference Alfaro1984; Hundt, Reference Hundt, Schubart and Ulreich1991): currently, ninety-eight examples are known from twenty-two sites, almost all of which belong to Argaric contexts (Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013). The only exceptions outside the Argaric cultural area are fragments found in an infant burial in Cave no. 9 of Monte Bolón in the province of Alicante dated to around 1700 cal bc (Soler et al., Reference Soler, López, Roca, Benito, Botella and Azuar2008; Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013) (Figure 2) and a small fragment of fabric found in Stratum IV of dwelling VII in Cabezo Redondo, also in the province of Alicante (Soler, Reference Soler1987: 46). The great majority of the surviving linen fragments come from burial contexts, where they were preserved thanks to direct contact with metal objects. Most have Z-twisted threads and their thickness ranges widely between 0.2 and 1 mm, although those between 0.3 and 0.5 mm predominate. Notable variations are also found in terms of density (threads per centimetre) and in the number of threads of the warp with respect to that of the weft. Their number is usually between 4/7 and 14/24 per cm2, although a frequency between 12 and 14 per cm2 is usually repeated (Alfaro, Reference Alfaro1984; Hundt, Reference Hundt, Schubart and Ulreich1991).

Figure 2. Basket of esparto grass and linen fabric from Cave no. 9 at Monte Bolón.

There is very little evidence of possible fibre or fabric dyeing. One of the few examples of fabrics whose analysis revealed pigmentation remains was found in a burial in Cueva Sagrada I in Lorca (Murcia). These fragments have a reddish colour obtained by the deliberate dyeing of the fabric with madder (Rubia tinctorum L.) (Alfaro, Reference Alfaro and Eiroa2005: 237). The burial, dating to just before the Bronze Age, also contained a possible handloom with several fragments of linen thread around it and a wooden stick, interpreted as a spinning spindle, both deposited as grave goods next to the textile remains (Alfaro, Reference Alfaro and Eiroa2005: 230–34). This is the only evidence of textile tools deposited in graves dating to the end of the third millennium and the second millennium bc. Among the more than one thousand Argaric graves investigated, tools directly associated with textile production (spindle whorls or loom weights) are surprisingly absent. This is even more remarkable when compared to the evidence from Iron Age sites, in which clay whorls become one of the most important items found in women's graves (Rafel, Reference Rafel, González, Masvidal, Montón and Picazo2007).

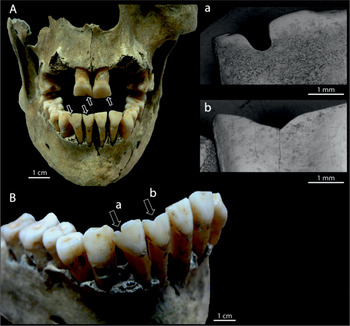

In Argaric female burials, it is however quite common to find tools associated with textile production other than spindle whorls or loom weights. According to a theory proposed some years ago by Risch (Reference Risch2002: 75), some men's social roles and position in political decision making was emphasized by their association with weapons, while the importance of women in social production processes, specifically in connection with garment production, was signalled through their association with metal awls, knives, and daggers found in their graves. Women would have played fundamental roles in the economy due to their association with textile activities. In this context, evidence of tooth wear, in the form of incisors with U or V-shaped grooves among some women buried at Cabezo Redondo (Romero, Reference Romero, Hernández, García and Barciela2016: 85–86) (Figure 3) and Castellón Alto (Lozano et al., Reference Lozano, Jiménez-Brobeil, Willman, Sánchez-Barba, Molina and Rubio2020), has been interpreted as having been related to spinning or to the processing of fibres. Similar evidence has also been documented in other areas of the Iberian Peninsula (Fidalgo et al., Reference Fidalgo, Silva and Porfírio2019).

Figure 3. Incisors with U- or V-shaped grooves belonging to a young woman buried at Cabezo Redondo (Romero, Reference Romero, Hernández, García and Barciela2016: 86). Photograph reproduced by permission of A. Romero.

Domestic Contexts

Little evidence of fibre remains has been recorded in domestic settings; but wool, flax, and other plant fibres, such as rush, bulrush and, above all, esparto grass, have nevertheless been recovered.

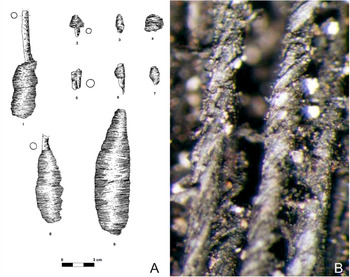

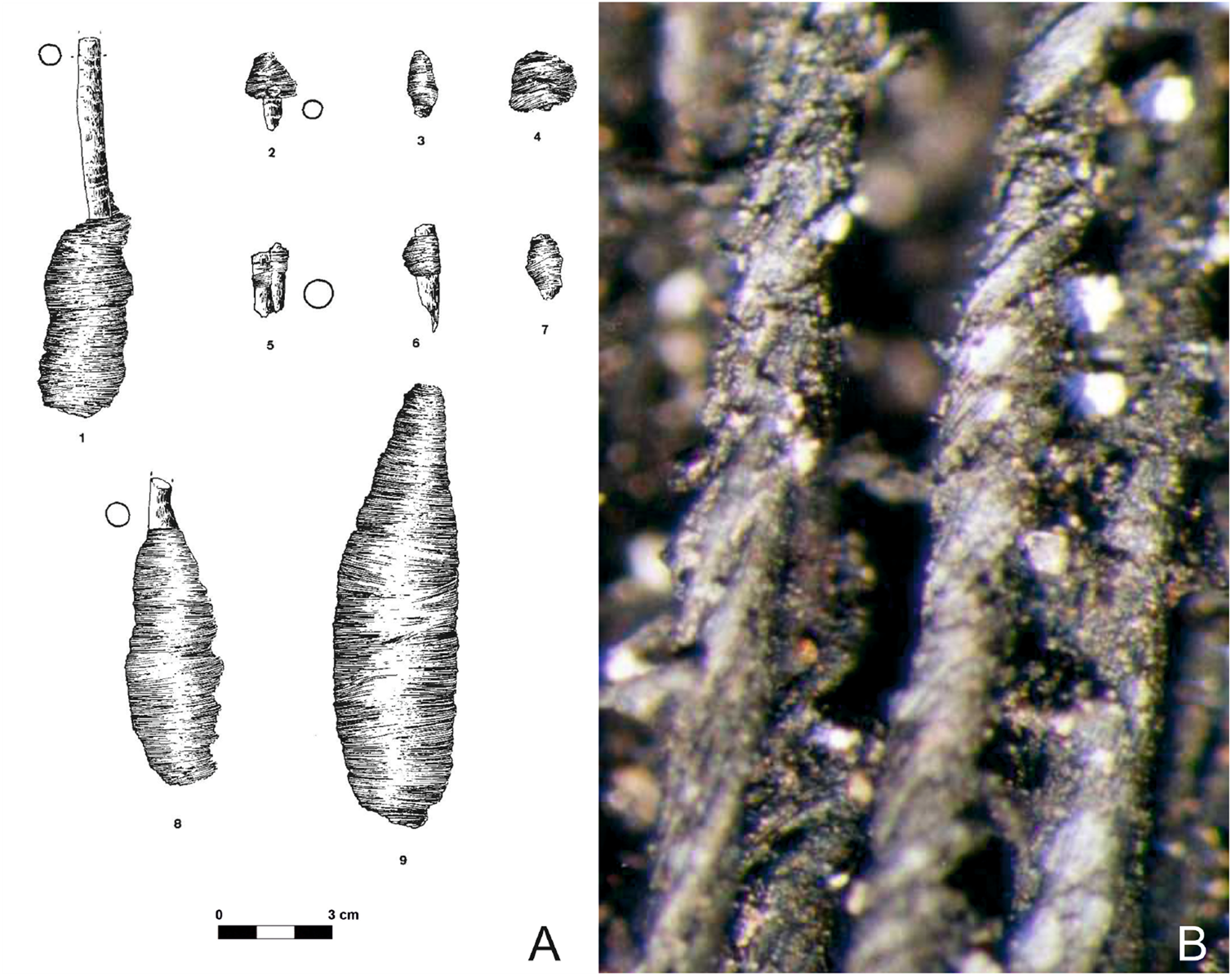

Until now, wool has only been identified in Castellón Alto, in the form of a mass of carbonized matter with a foam-like appearance (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Rodríguez, Cámara and Moreno2000: 89; Rodríguez-Ariza & Guillén, Reference Rodríguez-Ariza and Guillén2007: 67). Rushes, on the other hand, have been recorded on bobbins of thread stored at the settlement of Terlinques in the province of Alicante (Jover et al., Reference Jover, López, Machado, Herráez, Rivera, Precioso and Llorach2001) (Figure 4A and B). Another similar bobbin or spindle with yarn was documented at Motilla de Santa María del Retamar in the province of Ciudad Real (Galán & Sánchez Meseguer, Reference Galán, Sánchez, Sánchez Meseguer, Galán, Caballero, Fernández Ochoa and Musat1994: 99), although in this case the fibres were not identified.

Figure 4. A: set of rush fibre bobbins from Terlinques. B: detail of the thread on bobbin no. 9.

Flax and esparto have been found in almost one hundred archaeological contexts (Ayala & Jiménez, Reference Ayala, Jiménez, Vilar, Peñafiel and Irigoyen2007; Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013: 166–67, fig. 20). Flax seeds have been recovered at a number of sites (Buxó & Piqué, Reference Buxó and Piqué2008; Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete and Risch2015a, Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete, Risch, Celdrán and Freigeiro2015b) and, to a lesser extent, as fibre and fabrics on sites such as El Oficio (Alfaro, Reference Alfaro1984: 123) and Castellón Alto (Rodríguez-Ariza & Guillén, Reference Rodríguez-Ariza and Guillén2007: 63) in the El Argar region, Cabezo Redondo (Soler, Reference Soler1987) in the Valencian Bronze Age region, and El Cerro del Cuchillo (Hernández & Simón, Reference Hernández, Simón, Blánquez, Sanz and Musat1993) in the La Mancha Bronze Age region. A similar situation is documented among finds of esparto, which was not only used in rope making, basket weaving, and as a building material, but also in fashioning garments (Molina et al., Reference Molina, Rodríguez-Ariza, Jiménez-Brobeil and Botella2003).

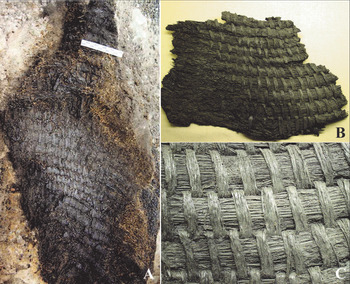

The archaeological record indicates that esparto grass, which grows naturally in the semi-arid climate of the south-east and east of the Iberian Peninsula, was the main fibre used in basketry (Figure 5) and rope making (Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013), resulting in a wide range of items associated with storage and transport, agricultural tasks, cattle husbandry, house building, clothing, and footwear. Baskets, mats, and ropes used in construction and as handles for ceramic vessels are among the best-preserved (generally charred) remains, although sandal soles have also been documented in Cabezo Redondo (Soler, Reference Soler1987: 78) and in Castellón Alto (Rodríguez-Ariza & Guillén, Reference Rodríguez-Ariza and Guillén2007: 69). Excavations carried out from the 1950s to the present on numerous sites with chronological sequences from 2100 to 1300 cal bc show their abundance and quality (Soler, Reference Soler1987; Jover et al., Reference Jover, López, Machado, Herráez, Rivera, Precioso and Llorach2001; Rodríguez-Ariza & Guillén, Reference Rodríguez-Ariza and Guillén2007; Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013). Esparto grass was clearly an extremely important raw material, even though its supply, selection, preparation, and manufacture were probably undertaken strictly at a household level.

Figure 5. A and B: basket of esparto grass containing cereals and bobbins, found in Terlinques. C: detail of the crossed weft of raw and crushed esparto in the basket.

Tools for producing textiles, such as needles, bone and metal punches, copper knives and daggers, spacers, and spools, have also been found on several of the sites mentioned above. These objects were used in various tasks such as basketry, weaving, and sewing (Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013).

Spindle whorls and loom weights are the most common objects most directly associated with spinning and weaving that survive in the archaeological record (Table 1). In the Iberian Peninsula, spindle whorls date back to the Late Neolithic (López Mira, Reference López Mira1995), but their use spread throughout the south-east from the third millennium bc onwards. There is considerable variation in the form of spindle whorls, in terms of morphology, weight, and material. Clay, stone, antler, and bone spindle whorls are all documented. In the second millennium bc, most whorls were made of clay and the most common shapes were discoidal and biconical. Discoidal whorls, the most common type from the Copper Age to the middle of the second millennium bc, have been recorded at various Argaric sites, such as Zapata, El Argar, and Fuente Álamo (Siret & Siret, Reference Siret and Siret1890). Examples have also been found on sites on the periphery of the Argaric area, such as at Cabezo Redondo (Soler, Reference Soler1987: 112). Also included in this group are spindle whorls made from deer antler (Basso & López, Reference Basso and López2019), which have been widely recorded from the middle of the second millennium cal bc onwards, at sites such as Cabezo Redondo (López Padilla, Reference López Padilla2011) and La Almoloya in the El Argar region (Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete, Risch, Celdrán and Freigeiro2015b: 102). Biconical whorls, or rarer examples with an irregular cross-section, similar to a bi-truncated cone, all made of clay, have been found at El Argar, Cabezo Redondo, Laderas del Castillo, San Antón de Orihuela, Tabayá, and Terlinques (Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013).

Table 1. Bronze Age periods in eastern Iberia with textile tools and products in radiocarbon-dated contexts.

Generally speaking, spindle whorls are relatively rarely found on excavated Bronze Age sites. It may be that some were made of wood or other perishable materials, or a spinning technique called splicing that did not require a spindle was used (Basso, Reference Basso, Márquez, Navalón-García and Soler2019; Gleba & Harris, Reference Gleba and Harris2019). Be that as it may, the situation changed significantly in the Late Bronze Age, and particularly in the Iron Age, when whorls began to be commonly deposited as grave goods in female burials (Rafel, Reference Rafel, González, Masvidal, Montón and Picazo2007).

By contrast, loom weights are encountered far more frequently. They are usually made of clay and vary in shape (oblong, ovoid, or cylindrical), size, weight, and number of perforations (between one and four) (Jover & López, Reference Jover and López2013; Basso, Reference Basso, Márquez, Navalón-García and Soler2019). They are often found in variable quantities, in piles or in more isolated groups of fewer pieces, within domestic spaces or in open areas on settlements.

It appears that warp-weighted looms were the most common type of loom documented archaeologically (Alfaro, Reference Alfaro1984: 94–106; Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Rodríguez, Cámara and Moreno2000). The discovery of groups of weights at various settlements, some aligned and associated with burnt rectilinear timbers (Figure 6) and some even with spindle whorls or remains of yarn nearby, has enabled us to infer the presence of looms and textile production areas in different contexts. However, the presence of a set of weights does not necessarily imply the existence of a loom. In some cases, the weights may simply have been stored, while, in others, they may have been reused to construct ovens or other structures (Basso, Reference Basso and Cutillas2018a).

Figure 6. Concentration of loom weights found next to a carbonized beam in Cabezo Redondo. Photograph reproduced by permission of M.S. Hernández.

More than twenty sites with concentrations of loom weights are currently known (Figure 7). On some of these, including Tira del Lienzo (Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete and Risch2015a: 194), Los Cipreses, and Lloma de Betxí (De Pedro, Reference De Pedro1998), these concentrations appeared in a single building. On other sites, such as La Almoloya (Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete, Risch, Celdrán and Freigeiro2015b: 104), Peñalosa (Contreras, Reference Contreras2000: 129), and Cabezo Redondo (Soler, Reference Soler1987), large concentrations have been recorded in several buildings, and in some of these, as in Peñalosa, loom weights were found in unequal numbers, in ten different locations within the settlement.

Figure 7. Distribution of archaeological sites with loom weight concentrations.

Significant differences become evident when the numbers of loom weights in the concentrations are compared to the types of weights found. Generally, the large heavy loom weights with four perforations, which are earlier and date between 2200 and 1750 bc, appear concentrated in small groups of between two and ten weights (Basso, Reference Basso, Bustamante-Álvarez, Sánchez López and Jiménez Ávila2020). In some cases, however, as in Lloma de Betxí (De Pedro, Reference De Pedro1998) (Figure 8) and Castell d'Almizra, clusters of more than twenty stacked loom weights have been found. These could be interpreted as stored weights, rather than indicating the position of a loom (Basso, Reference Basso and Cutillas2018a).

Figure 8. Concentration of oblong loom weights from the settlement of Lloma de Betxí. Photograph reproduced by permission of M.J. De Pedro.

From 1800/1750 cal bc onwards, we begin to see changes in the morphology, size, and weight of the loom weights, and in the numbers found together. These later weights tend to be cylindrical, smaller and lighter, and with fewer perforations. Often groups of more than twenty weights have been found. Observing this change has led us to consider the number of loom weights required to operate a warp-weighted loom. In the case of large oblong loom weights, recent studies suggest that no more than about ten weights were required (Basso, Reference Basso2018b: 61, Reference Basso, Bustamante-Álvarez, Sánchez López and Jiménez Ávila2020), whereas many more smaller and lighter weights, such as those frequently used from c. 1750 cal bc onwards, would have been needed to create a textile of a similar size.

Cabezo Redondo, one of the few Bronze Age sites to have been extensively excavated, has yielded the greatest amount of information on the subject of loom weights. Here, various concentrations of cylindrical weights have been found in many buildings, and in open spaces used for circulation (Soler, Reference Soler1987; Hernández et al., Reference Hernández, García and Barciela2016) (Figure 9). Of particular note are two groups of about fifty loom weights associated with carbonized timbers in two dwellings, House XVIII and within the circulation space close to House XXVII. Another group of thirty-six weights was found in House XV. Groups of weights associated with carbonized timbers have also been recovered in Castellón Alto (Contreras, Reference Contreras2000: 129) and El Rincón de Almendricos (Ayala, Reference Ayala1991: 174).

Figure 9. Cylindrical loom weight from Cabezo Redondo with suspension wear.

Concentrations of loom weights have also been found next to entranceways; as at Peñalosa, next to the entrances of houses IV and VI. The entrance of the latter house is directly connected to a yard that produced evidence for metallurgical production (Contreras, Reference Contreras2000: 132, note 2).

This association of groups of loom weights with passageways, open spaces, and with some of the larger buildings in the settlements, where a number of other production activities took place, is quite common. Another good example is provided by Building H1 at Tira del Lienzo (Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete and Risch2015a: 194): there, loom weights were found alongside grinding tools, various vessels, and silverwork (Delgado-Raack et al., Reference Delgado-Raack, Lull, Martin, Micó, Rihuete and Risch2015).

Discussion

When attempting to gain an insight into the everyday life of prehistoric groups through archaeology, it is essential to characterize the ways in which these communities organized their production and consumption, understand how activity areas were structured and associated with domestic units, and document the distribution of goods inside settlements and within a region.

The presence of spindle whorls, loom weights, looms, and graves containing the remains of garments or linen cloth in many excavated settlements, regardless of their size, location, or economic standing, suggests that the processes associated with spinning, weaving, and making textiles were normal everyday tasks, some of them seasonal in nature (Bender Jørgensen et al., Reference Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Stig Sørensen2018: 71–73). We therefore do not believe that there was craft specialization or specific storage sites in the eastern Iberian Peninsula in the Bronze Age, in contrast to the situation in other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamia (McCorriston, Reference McCorriston1997; Killen, Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007; Nosch et al., Reference Nosch, Koefoed and Andersson Strand2012). To date, we have no evidence for the existence of exchange systems, although it is presumed that these did exist. Nor is it possible to suggest how production was organized, for example whether each domestic group was self-sufficient and produced its own textiles and garments, or whether some activities, including textile manufacture, were managed collectively within each settlement, or even whether textile production, distribution, and exchange were largely controlled by the elite, given the social value of fabrics.

It appears that, in extensively excavated settlements, only a few areas (generally no more than two or three) show clear evidence of activities associated with textile production. This would speak against individual households being self-sufficient (Jover et al., Reference Jover, López, Pastor and Basso2020), since it indicates a concentration of textile production only in certain areas of each settlement. Nevertheless, these few textile production areas are not sufficiently large to indicate specialized workshops; moreover, they share space with other household production and consumption activities. To better resolve such questions of spatial organization, we must first endeavour to acquire more and better-quality data on the depositional and post-depositional history of the contexts excavated.

Studies of the faunal remains from both small and large settlements indicate an intensive use of the secondary products derived from domestic livestock, including wool (Andúgar & Saña, Reference Andúgar and Saña2004; Rizo, Reference Rizo2009), even though flock management was not exclusively geared towards the production of wool. This suggests that the composition and management of herds was probably controlled by each domestic or family group and designed to meet their wide-ranging needs, at least in part.

The flax stems and seeds from most of the extensively excavated settlements indicate that the cultivation of flax was probably widespread, taking advantage of the favourable growing conditions in the south-eastern Iberian Peninsula. We therefore propose that there was a high level of use of other plant fibres, such as esparto, reed, and rushes for basketry, ropes, construction material, and clothing. These plant species are abundant, easily and widely accessible in many areas of the south-eastern Iberian Peninsula and were therefore likely to be available to domestic or family groups and communities.

It should thus not be surprising that looms or other evidence of textile production have been found in almost all types of sites: farms or villages located on the plain, such as Rincón de Almendricos and Los Cipreses (Ayala, Reference Ayala1991), small fortified settlements, such as Caramoro I (Jover et al., Reference Jover, Pastor, Basso, Martínez and López2019), medium-sized settlements with clearly diverse production activities, such as Castellón Alto (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Rodríguez, Cámara and Moreno2000) and Peñalosa (Contreras, Reference Contreras2000), and large central settlements such as El Argar (Siret & Siret, Reference Siret and Siret1890) and Cabezo Redondo (Hernández et al., Reference Hernández, García and Barciela2016).

The oblong loom weights with four perforations can provide us with a number of interesting insights. Taking into account the seasonality of textile production (Bender Jørgensen et al., Reference Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Stig Sørensen2018: 71–73), the fact of finding these loom weights in large groups, and in numbers that far exceed what would be required for just one vertical loom, leads us to consider that the looms were not permanently set up and that elements of the loom, such as the weights, would have been stored somewhere within the domestic space. Furthermore, and even more importantly, these large groups of weights may also indicate the spaces where the domestic groups stored possibly all of their textile-making equipment, to be deployed among members of communities when textile production was required (Basso, Reference Basso2018b, Reference Basso, Bustamante-Álvarez, Sánchez López and Jiménez Ávila2020).

The same may also be true for the manufacturing areas. The best example of the possible centralization of the production of implements associated with textile work is found in El Argar. Here, the Siret brothers excavated two groups of 600 loom weights—500 and 100, respectively—which had been abandoned during the firing process (Siret & Siret Reference Siret and Siret1890: 157). Although they were small and light loom weights, the numbers found greatly exceeded the number of weights required for a loom, even a large one.

Vicente Lull (Reference Lull1983: 255) interpreted this as clear evidence of labour specialization. Without ruling out this interpretation, we believe that this at least indicates the concentration and centralization of the means of production, either during the manufacture of these weights or their subsequent storage for later distribution within the household or community (Basso, Reference Basso2018b: 61).

On several extensively excavated sites, including Peñalosa (Contreras, Reference Contreras2000: 129) and Tira del Lienzo (Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete and Risch2015a), textile production areas shared the same space as other craft activities of high social value, such as metallurgy and jewellery production. There is also evidence that loom weights were stored in large buildings where cereals were processed and stored, as in Lloma de Betxí (De Pedro, Reference De Pedro1998). The finding of a loom alongside evidence of grain processing and other craft activities within the largest room at El Cerro del Cuchillo (Hernández & Simón, Reference Hernández, Simón, Blánquez, Sanz and Musat1993) constitutes a further example. This tendency to concentrate activities in a single building or room that appears to be associated with greater control over textile production processes, coincides in time and space with marked changes in space management within settlements (López Padilla & Jover, Reference López Padilla, Jover and López Padilla2014).

This period of change observed in settlements seems to coincide with a progressive standardization among certain textile tools, such as loom weights and spindle whorls. Around 1800/1750 cal bc, oblong loom weights disappeared, as new types emerged. Cylindrical loom weights began to dominate the archaeological record, at first with two perforations, finally giving way to a single central perforation. Concurrently, biconical ceramic spindle whorls became common. All these technological changes indicate not only a major standardization in textile tools but also the introduction of improvements in textile production and, possibly, a higher degree of craft specialization.

Conclusions

More than a century of archaeological research on the Bronze Age in the eastern Iberian Peninsula has led to the definition of different archaeological cultures, with differing degrees of social and economic development. Among these, the Argaric culture stands out for the size of its settlements, the investments made in large-scale infrastructure works, and a marked degree of ritual behaviour (Lull, Reference Lull1983; Cámara, Reference Cámara2001; Aranda et al., Reference Aranda, Montón-Subias and Sánchez Romero2015).

The archaeological evidence shows that, throughout the eastern Iberian Peninsula, there was an in-depth knowledge of the properties of plant and animal fibres used to make clothing, basketry, and ropes. Linen and wool were used to create textiles for clothes, covers, and bags; while other fibres such as bulrushes, and particularly esparto grass, were employed in the manufacture of items associated with storage, transport, protection, furnishing, footwear, etc. This clearly shows the importance of the crafts associated with textile production in the activities and everyday lives of those Bronze Age communities.

The procurement, exchange, and distribution of wool and linen, both fundamentally associated with weaving, and of esparto grass and other similar plant fibres used in basketry and rope work, have several social and economic implications. Wool may have been obtained on a domestic scale by communities or kinship groups raising small flocks of sheep. In this sense, the absence of large flocks, necessary for a supra-domestic consumption (Sabatini & Bergerbrant, Reference Sabatini and Bergerbrant2019), leads us to propose that wool production was limited to the household sphere and less developed than the production of bast fibres. We also contend that specialized labour did not exist in Bronze Age eastern Iberia, nor did the levels of production and exchange operate on the same scale as, for example, in Mesopotamia (McCorriston, Reference McCorriston1997; Algaze, Reference Algaze2008), Egypt (Lucas & Harris, Reference Lucas and Harris1962; Vogelsang-Eastwood, Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood1992), the Aegean (Killen, Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007; Militello, Reference Militello, Gillis and Nosch2007), or even some parts of Europe, such as northern Italy (Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Earle and Cardarelli2018). Rather, the textile production in our area of study appears to be related to an incipient gender-based division of labour (Lozano et al., Reference Lozano, Jiménez-Brobeil, Willman, Sánchez-Barba, Molina and Rubio2020) that arose within kinship groups and that, at best, had the potential to promote small-scale exchange processes.

The production of linen, with flax probably cultivated from the third millennium cal bc onwards in numerous parts of the Iberian Peninsula, appears to have followed a similar trajectory. Flax production, transformation, and exchange may have been more frequent than indicated by research conducted so far, as this has focused more on non-perishable objects than on the products of weaving. Research elsewhere in Europe and Mesopotamia (Barber, Reference Barber1991; Gillis & Nosch, Reference Gillis and Nosch2007; Algaze, Reference Algaze2008), clearly shows that the production of clothing played a prominent role in the economy of late prehistoric societies undergoing processes of social and political stratification. The scarce but significant evidence that we have been able to gather in the south-eastern Iberian Peninsula attests to this.

Textile production would only later become a full-time specialized activity in the eastern Iberian Peninsula, with the improvement in transport and the rise of social demands and differentiation. Alongside the continuing household production of fabrics and basketry to meet local needs, specialist craftspeople began to emerge. They specialized in the production of fabrics for the elite that were exceptional for the quality of the thread used, their weaving and treatment, while other people were fully employed in transporting and treating the fibres. In some regions, for example in Lower Mesopotamia, these processes have been recorded from the fourth millennium bc onwards (Algaze, Reference Algaze2008), whereas in the Iberian Peninsula there is insufficient evidence so far to suggest that this was the case.

It would appear that production within kinship groups remained predominant and that the elites had not yet developed the mechanisms required to control the production and distribution of textile goods. Nonetheless, within the Argaric area, the concentration of specific weaving tasks in certain buildings where other socially important activities such as metalworking, silversmithing (Delgado-Raack et al., Reference Delgado-Raack, Lull, Martin, Micó, Rihuete and Risch2015), and even ivory carving (López Padilla, Reference López Padilla2011) were carried out allows us to suggest that the communities of the El Argar culture had taken at least the first steps towards controlling their production and distribution.

Acknowledgements

This research was developed within the Prehistory and Protohistory Research Group of the University of Alicante (Spain) (VIGROB-098) and undertaken within the framework of the research project ‘Social and frontier spaces during the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age in the Eastern Iberia Peninsula’ (HAR2016-76586-P), funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de España. We would like to thank María Pastor Quiles and Dan Miles for revising our text.