Introduction

A common expectation in the interest groups literature is that the influence of a given interest group is primarily determined by the resources at its disposal (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner and Berry2009, Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2014, Klüver Reference Klüver2013), so much so that policy outcomes that deviate from this pattern are puzzles to be explained (Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2014, 1214).

In this article, we address one such puzzle with regard to the different outcomes of the reforms of pharmacy regulation in Portugal and in Greece between 2005 and 2021. Both countries were pressured by the European Commission to increase competition in the retail pharmacy sector, and, following the 2010 financial crisis, in both Portugal and Greece reforms of the sector were included in the structural reforms required by their international creditors, the so-called Troika of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.

Contradicting the theoretical expectations connecting material resources to policy influence, the reforms implemented in both countries upset the interests of pharmacists much more fundamentally in Portugal than in Greece, even though the Portuguese pharmacies’ association has far larger financial, organizational, and informational resources. This article argues that different sociopolitical reputation of pharmacists and their associations in the two countries explains this puzzle.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. ‘The puzzle’ section presents our empirical puzzle. The ‘Reputation and policy influence’ section develops our argument building on the scholarship on reputation in management, public sector and interest groups literature. The next section presents our research design and analytical strategy. The section ‘Reforming pharmaciues in Portugal and Greece’ discusses the two cases in relation to our argument. A discussion follows. The article concludes by highlighting its theoretical contribution and avenues for further research.

The puzzle

At the beginning of our study period (2005), pharmacies were highly protected in both Greece and Portugal. In the early 2000s, the average regulation intensity index of pharmacies for the then 15 Member States of the European Union was 6.7; in Greece it was 8.9 and in Portugal 8 (Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Fink, Ogus, Merz, Fink and Berrer2003, 3). Pharmacies had a monopoly over the sale of medicines (including over-the-counter [OTC] products) and strong barriers existed to the opening of new pharmacies (restrictions on the number of pharmacies in relation to the population, a minimum distance between two pharmacies, limits to ownership).

In both countries, pharmacies were highly profitable. Greek and Portuguese pharmacies had high profit margins (35% in Greece and 20% in Portugal) (Duarte Oliveira and Gouveia Pinto Reference Duarte Oliveira and Gouveia Pinto2005, Yfantopoulos Reference Yfantopoulos2008); and in both countries the volume and value of sales were relatively high. For example, while in 2005 an average Greek or Portuguese citizen would spend for the ten highest-selling products, 34 and 30 dollars a year, respectively, this amount was only 19 dollars in Austria and 23 dollars in Finland (Leopold et al. Reference Leopold, Mantel-Teeuwisse, Vogler, Valkova, Joncheere, Leufkens, Wagner, Ross-Degnane and Laing2014). Similarly, in 2005 the average expenditure in pharmaceuticals as a share of GDP was quite higher than the OECD average (more than 2% for Greece and Portugal as compared to the 1.5% average) (OECD 2018). Table 1 summarizes the regulatory framework for pharmacies (columns 2–6) as well as several fundamental economic features of the sector (columns 7–10) in 2005.

Table 1. Pharmacies in Greece and Portugal: regulatory context and economic outcomes in 2005

1 Sources: Greece: Lambrelli and O’Donnell (Reference Lambrelli and O’Donnell2011); Portugal: Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Santos and Silveira2006).

2 Source: Paterson and et al. (Reference Paterson, Fink, Ogus, Merz, Fink and Berrer2003).

3 Source: Greece: Yfantopoulos (Reference Yfantopoulos2008); Portugal: Duarte Oliveira and Gouveia Pinto (Reference Duarte Oliveira and Gouveia Pinto2005).

4 Source: Leopold and et al. (Reference Leopold, Mantel-Teeuwisse, Vogler, Valkova, Joncheere, Leufkens, Wagner, Ross-Degnane and Laing2014).

5 Source: OECD (2018).

6 Constant dollars per capita for the 10 highest-selling products in each country.

7 Standard unit per capita 10 highest-selling products in each country.

However, Portugal and Greece took different paths. The Greek governments were forced to reduce the prices of medicines and the profit margin of pharmacies during the economic adjustment programs (EAPs), but they did not implement most of the reforms liberalizing pharmacies included in the memorandum of understanding (MoU) with its creditors. Conversely, not only did Portuguese governments significantly reduce pharmacies’ profit margin and the price of medicines during the bailout, but they also had introduced several measures deregulating pharmacies years before Portugal agreed to its EAP.

These diverging outcomes present a puzzle for the established resource exchange explanations of interest groups influence since, as the empirical section shows, the Portuguese pharmacists’ association is more powerful than its Greek counterpart in terms of material and institutional resources.

Indeed, the divergence in reform outcomes cannot be explained by broader contextual factors. Greece and Portugal have similar political systems. They are unitary polities and relatively recent democracies (Afonso et al. Reference Afonso, Zartaloudis and Papadopoulos2015; Morlino Reference Morlino1998). Moreover, they have non-corporatist systems of interest intermediation, and in both countries interest groups tend to privilege interactions with government parties and are quite powerful (Lisi and Louriero Reference Lisi and Louriero2022; Siaroff Reference Siaroff1999).

Both Greece and Portugal are usually categorized as having clientelistic features in terms of the patronage links between parties, public administration, and society (Lisi and Louriero Reference Lisi and Louriero2022; Morlino Reference Morlino1998; Sotiropoulos Reference Sotiropoulos2004). While it has been argued that Greek governments are less willing and able to reform than their Portuguese counterparts because of stronger clientelistic features (Afonso et al. Reference Afonso, Zartaloudis and Papadopoulos2015), clientelism in Greece has been considerably weakened by the financial crisis and the involvement of external creditors for most of the period covered in this article (Sotiropoulos Reference Sotiropoulos2019). As a result, the capacity of Greek governments to reform is larger than one might expect; indeed, a larger number of conditions of the MoUs were fulfilled in Greece than in Portugal (80 versus 75%, respectively) (Moury Reference Moury, Ladi, Cardoso and Gago2021). Moreover, Greek governments successfully pursued many contentious reforms during the bailouts (including reforms of social security and of the public administration), while several reforms included in the Portuguese EAP, such as a social security reform, were never implemented (Moury Reference Moury, Ladi, Cardoso and Gago2021).

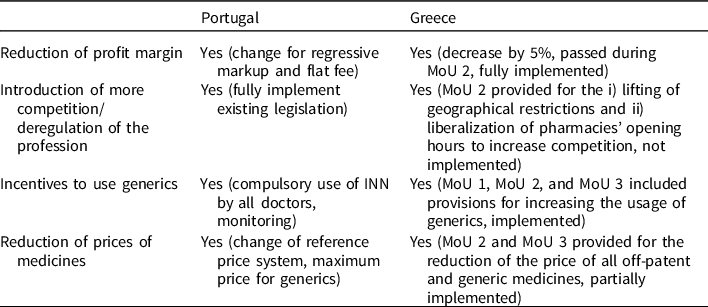

Finally, both Portugal and Greece, as EU members, were expected to implement the 2006 Services Directive’s mandate to increase competition in the professions. As discussed, moreover, both Greece (in 2010, 2012, and 2015) and Portugal (2011) requested international financial support. As a condition for these bailouts, the governments agreed to EAPs that included the introduction of cost-cutting and structural reforms in the pharmacy sector (see Table 2). Making the question still more puzzling, conditionality to implement structural reforms was more stringent in Greece than in Portugal given its deeper fiscal woes that required external financial support over 8 years (2010–2018) and three bailouts.

Table 2. Measures affecting pharmacies in the economic adjustment programs

Reputation and policy influence

What then explains the more extensive reforms of pharmacies in Portugal than in Greece? Our answer is that the sociopolitical reputation of an interest group has a role to play in explaining its capacity in advancing its policy goals. We define an interest group’s sociopolitical reputation as a reputation for behaving in an ethical manner and contributing to socially sanctioned goals. Such reputation derives from a group’s behavior and how this behavior is perceived by relevant audiences.

In this section, we discuss the concept of sociopolitical reputation, starting from the work on reputation in the public administration and management literatures, and then argue for its extension to the interest groups literature and particularly to the study of interest groups’ influence.

To start with, the literature on public sector and regulatory agencies as well as organizational and management studies has given the concept of reputation significant attention. In both fields, an actor’s reputation is based on how the relevant stakeholders or audiences perceive its behavior (Bromley Reference Bromley2001; Capelos et al. Reference Capelos, Provost, Parouti, Barnett, Chenoweth, Fife-Schaw and Kelay2016; Overman et al. Reference Overman, Busuioc and Wood2020). Reputation can also be neutral when audiences have not formed a strong positive or negative perception of an actor’s behavior (Godfrey Reference Godfrey2005; Luoma-aho Reference Luoma-Aho2007; Noe Reference Noe, Barnett and Pollock2012).

The concept of reputation has first been applied to the study of bureaucracy and especially regulatory agencies by Daniel Carpenter (Reference Carpenter2001, Reference Carpenter2010). In Carpenter’ work and in the work of the scholars that have followed him, organizational reputation matters insofar as it increases the autonomy of regulatory agencies and other bureaucracies from external actors (Bertelli and Busuioc Reference Bertelli and Busuioc2021; Carpenter Reference Carpenter2001, Reference Carpenter2010; Carpenter and Krause Reference Carpenter and Krause2015).

Scholars working on bureaucratic reputation have adopted Carpenter’s definition of reputation as “a set of symbolic beliefs about the unique or separable capacities, roles, and obligations of an organization, where these beliefs are embedded in audience networks” (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2010, 45), where audiences are the actors that are in a position to observe and judge the organization’s behavior. Carpenter lists four broad dimensions of an agency’s reputation: performative (how effective it is in achieving its goals), technical (how scientifically and technically proficient it is), legal procedural (how legally and procedurally correct its decision-making is), and moral (how ethical its goals and methods are) (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2010, 46–47). The latter dimension is the closest to what we call sociopolitical reputation.

The reputation of firms has also been the concern of several organizational and management scholars. These have discussed corporate reputation as an intangible asset that may produce benefits for firms, such as attracting investors, customers, and employees, increasing corporate lifespans, and discouraging competitors from entering the market (Aguinis and Glavas Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012; Barney Reference Barney1991; Baron Reference Baron2001; Fombrun Reference Fombrun, Hitt, Freeman and Harrison2006; Rao Reference Rao1994; Martinez et al. Reference Martinez, Russell, Maher, Brandon-Lai and Ferris2017).

Among the reputational strategies businesses can pursue, of immediate relevance to this article are those that fall under the broad heading of corporate social responsibility (CSR). CSR refers to voluntary actions that are not directly profit-seeking and are typically aimed at social and environmental goals (Benabou and Tirole Reference Benabou and Tirole2010; den Hond et al. Reference den Hond, Rehbein, de Bakker and Kooijmans-Van Lankveld2014).

Through CSR business can develop what Werner has called a positive “sociopolitical reputation” to refer to firms that pursue environmental or social activities that are valued by a politician’s constituency” (Werner Reference Werner2015). The organizational and management literature uses several different terms to refer to various aspects of the concept, such as reputation for being “other-regarding” or “doing good” (Kurucz et al. Reference Kurucz, Colbert, Wheeler, Crane, Matten, McWilliams, Moon and Siegel2008; Martinez et al. Reference Martinez, Russell, Maher, Brandon-Lai and Ferris2017; Tetrault Sirsly and Lvina Reference Sirsly, Ann and Lvina2019), reputation for using power responsibly (Kurucz et al. Reference Kurucz, Colbert, Wheeler, Crane, Matten, McWilliams, Moon and Siegel2008), moral legitimacy (Bitektine Reference Bitektine2011), or public reputation reflecting the extent of adherence to social norms and values (Deephouse and Carter Reference Deephouse and Carter2005). This good sociopolitical reputation could then be used to develop goodwill with a variety of stakeholders such as investors, customers, and employees (Fombrun et al. Reference Fombrun, Gardberg and Barnett2000; Gardberg and Fombrun Reference Gardberg and Fombrun2006; Walker and Rea Reference Walker and Rea2014) and the public at large (Fombrun and Shanley Reference Fombrun and Shanley1990).

Moving now to the interest groups literature, a key approach focuses on how interest groups exchange the resources at their disposal for access to policymakers (Beyers 2004; Bouwen Reference Bouwen2002), which in turn facilitates policy influence (Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015). Power, in the sense of the ability to influence policy to one’s advantage, results from the resources interest groups have at their disposal. Such resources include technical information (Bouwen Reference Bouwen2004; Chalmers Reference Chalmers2013), information on the policy preferences of other actors (Junk Reference Junk2019; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2007), organizational capacity (Albareda 2020) financial and political support for partisan actors (Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2014; Klüver Reference Klüver2013, Reference Klüver2020), and legitimacy (Fraussen et al. Reference Fraussen, Beyers and Donas2015; Maloney et al. Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994; van Kersbergen and van Waarden Reference van Kersbergen and van Waarden2004). In this literature, reputation has mostly been analyzed in terms of whether relevant audiences perceive an interest group to control crucial resources. For example, an interest group’s reputation for providing dependable information can affect its ability to influence regulators and policymakers (Bernhagen and Bräuninger Reference Bernhagen and Bräuninger2005; Bernhagen et al. Reference Bernhagen, Dür and Marshall2014; Braun Reference Braun2012; James 2018), as does a reputation for being able to mobilize public support (Beyers and Kerremans Reference Beyers and Kerremans2004; Braun Reference Braun2012). A reputation for being influential can further the ability of an interest group to cooperate with other groups (Heaney Reference Heaney2006, Reference Heaney2014; Leifeld and Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012). Along similar lines, Dowding (Reference Dowding2003) noted that a group who has won a reputation for being powerful might be able to obtain policy outcomes more than proportional to its instrumental resources. We thus can see that the interest groups literature largely ignores the role of sociopolitical reputation as a resource in its own right that can be used to get access and influence.

However, scholars from various other disciplines have also discussed how initiatives to improve a corporation’s sociopolitical reputation are complementary to more traditional lobbying activities (Bernhagen et al. Reference Bernhagen, Kollman and Patsiurko2022; Fisch Reference Fisch2005; Hadani and Coombes Reference Hadani and Coombes2015). Public health researchers illustrated, for example, how Philip Morris philanthropic activities have influenced public opinion and government officials in their favor (Tesler and Malone Reference Tesler and Malone2008). In management science, Werner (Reference Werner2015) finds that in the USA corporations with higher sociopolitical reputation (operationalized through an index of environmental, community, and diversity performance) have greater access to legislators. The explicit or implicit claim of these contributions is that CSR and other socially valued behaviors on the part of corporations can enhance their reputation with policymakers and thus facilitate their access to policymakers and their influence on policy.

Building on this work, we argue that sociopolitical reputation is an important determinant of interest group influence on policymakers. This happens for two reasons. First, because elected and non-elected policymakers might extrapolate from their socially responsible behavior that certain interest groups are more trustworthy and consequently more deserving of attention than others (Hadani and Coombes Reference Hadani and Coombes2015). Second, elected policymakers care about how the public views the actors they interact with and fear voters’ backlash if they appear to be protecting the interests of actors that voters dislike (Werner Reference Werner2015).

We thus argue that sociopolitical reputation should take its place alongside the resources usually considered by the interest groups literature, such as technical knowledge or organizational efficiency, in the explanations of interest group influence. Our hypothesis is: other things being equal, interest groups with positive or neutral sociopolitical reputation will be in a better position to influence policy than groups with negative sociopolitical reputation.

In the empirical section of this article, we assess this hypothesis by analyzing the different fates of the attempts to reform pharmacy regulation in Greece and Portugal. Before testing our argument, two caveats are in order. A first caveat regards how sociopolitical reputation relates to the concepts of salience and conflict. As for the former, Pepper Culpepper has argued that business is more influential when issues stay out of public view (Culpepper Reference Culpepper2010). However, others have noted that business might be successful when it manages both the attention and the support of the public for a particular policy (Keller Reference Keller2018). In our view, salience relates to an interest group’s sociopolitical reputation insofar as its behavior, if reported by the media, might attract the attention of the public and hence make salient the issues of concern for the interest group. Specifically, an interest group with negative sociopolitical reputation will likely not be harmed by its reputation as long as the issues that concern it are not salient with the public.

With regard to conflict, the more controversial a policy is, the more an interest group might find it difficult to promote its preferred outcome because of the counter-lobbying it will face (Klüver Reference Klüver2013). As Klüver explains, salience and conflict are not the same (interest groups might agree on a salient issue, or conflict might be high around an issue which is not salient for the public). They are, however, connected: if the status quo (or an attempted change from the status quo) implies significant costs for the less organized groups (and hence become salient for them), they will have an incentive to organize (Becker Reference Becker1983); hence, the degree of conflict around the issue will increase together with its salience. Moreover, an interest group’s sociopolitical reputation affects conflict in that public knowledge about unethical behavior of a firm/actor might cause other groups to counter-organize against it.

More generally, and this is our second caveat, our argument of course does not imply that sociopolitical reputation is the only determinant of an interest group’s capacity to advance its interests. What we argue is that sociopolitical reputation should be added to the set of resources interest groups might have available and use to influence policy. Just like corporate reputation is an economic asset in its own right (Fombrun Reference Fombrun, Hitt, Freeman and Harrison2006), so is sociopolitical reputation an instrumental resource alongside others such as financial resources, proximity or ideological affinity with decision-makers, or information for interest groups.

Moreover, power is not only instrumental, supporting actors’ purposeful lobbying, but can also be structural. Structural power is associated with actors’ position in the economy (Bell Reference Bell2012). Because of their dependence on business in terms of investment, employment, tax revenue, or provision of crucial public goods (Busemeyer and Thelen Reference Busemeyer and Thelen2020), governments are predisposed to adopt policies that benefit firms, without the latter having to actively do anything (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1977; Przeworski Reference Przeworski1985; Woll Reference Woll2019). A famous example of the consequences of structural power is the bailouts of banks: even though the risky behavior of bankers had been much criticized, banks were rescued because they were considered too big to fail (Hindmoor and Mc Geechan Reference Hindmoor and McGeechan2012, Woll Reference Woll2017). In this sense, some actors are “systematically lucky”: because of their role in capitalist economies, their preferences coincide with those of powerful actors, including governments, without having to explicitly pursue policy influence (Dowding Reference Dowding2003, Reference Dowding2021).

These considerations help us set the scope conditions for our argument. Sociopolitical reputation, whether positive or negative, will matter less for policy influence when actors are endowed with strong structural power. Specifically, sociopolitical reputation will matter more for small firms or professions that only or mostly rely on instrumental power resources than for big business.

Research design and analytical strategy

Case studies

Portugal and Greece are most similar cases, since, as discussed in “The puzzle” section, they share several relevant contextual factors (Mill Reference Mill2011, 463). By focusing on the pharmacist profession, this article also adopts a crucial case strategy (Eckstein 1975), in the sense that we assess our argument in a case where the conditions for its empirical confirmation are especially strong, so that its rejection would be a significant blow to its plausibility. Specifically, the effect of sociopolitical reputation on professions’ policy influence should be especially noticeable because they cannot count on structural power and also because they depend for their very existence on a generalized societal belief that they serve the public good (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Hardin and Levi2005, 110–113; Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2016).

The period covered extends between 2005, when the reform of pharmacy regulations first entered the political agenda in Portugal, and 2021. A time span of well over a decade is needed in order to follow the evolution of regulation with regard not only to the formal introduction of the reforms but also to their actual implementation (Sabatier Reference Sabatier1998). As a growing scholarship has shown, moreover, the relationship between interest groups and parties matters for the explanation of interest group influence well beyond the traditional connection between left or right parties and actors like unions or employer associations (e.g., Berkhout et al. Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Statsch2021; Chaqués-Bonafont et al. Reference Chaqués-Bonafont2021). The 2005–2021 saw significant government alternation in both countries, and we can thus also assess the impact of changing government parties on the reforms.

Operationalization of variables

Our broad research question is why some interest groups are more successful than others in influencing policymakers.

We operationalize our dependent variable as the extent to which reforms of the regulations regarding pharmacies in Greece and Portugal went against the preferences of the pharmacists’ associations in the two countries. This was assessed through the preference attainment approach, namely based on the distance between the associations’ ideal points and the policy outcomes (Dür Reference Dür2008). Actors’ preferences are often uncontroversial (say, maximizing profits), including in the case of pharmacy liberalization in Greece and Portugal, as in both countries the reforms aimed to decrease profit margins and increase competition. As regards the independent variables, we look at the reputation of pharmacists’ associations with public officials, as elected officials and bureaucrats are the relevant “audience networks” (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2010, 45). As an interest group’s reputation will also depend on the behavior of the societal interests it represents (Tirole Reference Tirole1996), in the empirical section we consider the reputation of pharmacists as well as of the associations that represent them.

Data collection

In order to assess reputation, and the causal link between reputation and the reforms, we have combined interviews and documentary sources. First, elite interviews were carried out to assess the preferences of the association as well as their reputation with elected officials (Fairfield Reference Fairfield2015; Heaney Reference Heaney2014). We interviewed 17 respondents (9 in Portugal, 8 in Greece): politicians that were in the government during the reform attempts, as well as political advisors and other experts who had been working in the pharmaceutical sector during this period, and members of the pharmacists’ associations.

In Portugal, five former ministers, junior ministers, or Members of Parliament who had dealt with pharmacy regulation were interviewed, three in 2017 in the context of a related research on health sector reforms and the pharmaceutical industry (Teixeira Pereira Reference Diogo, Moury and Pita Barros2023), and two in 2020 especially for this article. For this article, in 2020 we also interviewed four experts that the government regularly consulted when making policies in the health sector. In Greece, eight interviews were conducted for this article in 2020 and 2021. They included three government members for the period under study, one political advisor- expert with extensive experience on the reform of pharmacies, and four members of the Panhellenic Association of Pharmacists (PPA) with different ranks and responsibilities in the association.

Interviewees were contacted by email, asking for an interview in person or by Zoom. The interviews were recorded with their consent. Interviews lasted an average of 40 minutes. The interviews were on condition of anonymity. Questions to interviewees included: For which reasons were the regulation of pharmacies put on the agenda? What were the positions of pharmacies and of the government on the reforms X (for each reform attempted in the period 2005–2021)? What can explain the results of the law-making process? How do you assess the power of pharmacies? And of their association? Would you say that they bring a positive value to society? Would you say that they behave ethically and lawfully? Which factors explain the failure of attempts to reform the sector? Which factors explain the success of (X) reform? Would you say that the pharmacies are (too) powerful? Which are the sources of their power in your opinion?

Second, we used primary and secondary sources, such as legislation, the EAPs for the two countries, political memoirs, reports by the EU, the World Health Organization and the European pharmacists’ association (Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Fink, Ogus, Merz, Fink and Berrer2003; PGEU Various years; WHO 2019), information from pharmacists’ associations, and national secondary literature. Our goal was, first, to triangulate the interviews on the preferences and sociopolitical reputation of the associations and, second, to develop an understanding of the contextual factors that may affect the government’s willingness and capacity to reform the pharmacy sector.

To complement those sources, we adapted Werner’s strategy of using CSR activities as an additional indicator of the sociopolitical reputation of corporate actors (Werner Reference Werner2015). In our case, we look at the key dimensions of pharmacists’ socially responsible behavior, namely whether pharmacies in both countries freely provide what the World Health Organization calls advanced professional services from pharmacies, such as “chronic disease management; early screening and testing; vaccination; smoking cessation; and measurement of blood pressure, cholesterol and glucose” (WHO 2019, 46).

Reforming pharmacies in Portugal and Greece

Portugal

Since 1979, the Portuguese public healthcare system has been based on a National Health Service structure with universal coverage and almost free access, which is financed by the State budget. Medicines prescribed by both public and private doctors are reimbursed by the State depending on their types; pharmacies advance the cost of the medicines to their customers and bill the state monthly for reimbursements that often arrive late (see below).

Public opinion on pharmacies is mixed. Policarpo et al. (Reference Policarpo, Romano, António, Correia and Costa2019) have showed that, while a great majority (94%) of Portuguese users were at least globally satisfied with their experience with pharmacies, for one-third (29%) there could be more services available that are currently provided by other healthcare facilities. Indeed, and contrary to Greece, pharmacies offer few free services: the only service that the pharmacies provided for free was a free needle exchange, which was stopped in 2012. Since 2007, pharmacies also offer a series of services (diabetes testing, nutrition, etc.) that clients must pay out of pocket.

Three organizations represent pharmacies in Portugal: the Order of Pharmacists, which regulates the profession, and two associations representing the interests of pharmacies: the Portuguese Association of Pharmacies (APF) and the National Association of Pharmacies (ANF). The latter is by far the most powerful. It was created in 1975 and today represents approximately 97% of pharmacies in Portugal (P9). It is often the only interlocutor of the government, and it is much more present in the media than the Order or AFP (Araújo and Lopes Reference Rita and Lopes2014).

A very important source of power for the ANF derives from an agreement it made with the State in 1988, whereby Finanfarma, the financial arm of the ANF, would advance to its members government refunds for medicines (these were sometimes paid with years of delay). As noted by the Portuguese competition authority, this has granted ANF a powerful position vis-à-vis both the State and pharmacies, which has long prevented governments from reforming the sector. Footnote 1 As a previous minister explained: “This was an unacceptable situation of dependence of the State, the State was captured by ANF” (P2). Such arrangement has also made it very costly for pharmacies to leave the ANF: the threat (and occasional occurrences) of expulsion of pharmacies and consequent loss of prompt refunds have contributed to the exceptional membership rate and compliance of members with the policies devised by the national executive (Evans Reference Evans2008).

Precisely to reduce the influence of the ANF, in 2006 the Health Ministry created a fund that would allow the State to pay pharmacies on time (P2). In response, Finanfarma announced that it would reimburse 22 days earlier than the State and would provide some further financial services to pharmacies. Following the 2010 financial crisis, the State again delayed payments, and in 2014 the public fund was extinguished. Today, Finanfarma continues to advance refunds to ANF members at an 8.5% interest rate (Pinto Reference Pinto and Ferreira2018).

On top of the interest payments that it receives from both the State and pharmacies, the association started a cooperative that sold a single IT system for pharmacies (Evans Reference Evans2008). This cooperative later developed into a consultancy company that sells pharmaceutical and health data. Beside generating significant profits (P 8), the cooperative has made the State dependent on the ANF for crucial health information (Evans Reference Evans2008). The cooperative’s profits have then been re-invested in holdings in the production of pharmaceuticals, drug distribution, and private hospitals. ANF’s assets are today worth more than 700 million euros. Footnote 2 These overlapping interests have caused the Portuguese competition authority to often find against the ANF for abuse of dominant position. Footnote 3

This financial empire has given ANF the financial means to influence decision-makers. Although not directly (as it would be illegal), each member of the ANF board has allegedly subsidized the electoral campaign of every party in Parliament (P2, P3, P4), and the ANF regularly pays consultancy fees to members of Parliament or of the government (Evans Reference Evans2008) (P1, P3).

Unsurprisingly then, the experts and policymakers we talked to refer to the ANF using terms such as “Mafia” and “State capture” (P1, P3, P4, P10, see below for some quotes). This view chimes with that of Portuguese citizens and of the press. On-line polls in 2012 showed that pharmacies are considered to be one of the most powerful lobbies in the country, after the Catholic Church, doctors, banks, and lawyers, but before trade unions, business, academics, and the military. Footnote 4 Perusing editorials in two newspapers of record (Público, Diario das Noticias), we found 35 editorials that stigmatized the excessive power of the ANF or of pharmacies between 2005 and 2021. In sum, citizens and policymakers alike see the ANF and pharmacists as a powerful lobby that does not serve the public interest well. Moreover, as discussed above, this negative reputation is not compensated by free health services provided by pharmacies.

When the Socialists formed a new government in 2005 after winning a majority of seats in Parliament, one of the first statements of the Prime Minister José Sócrates and the health minister Correia de Campos was that they wanted to curb the privileges of pharmacies and the power of the ANF (Correia de Campos Reference Correia de Campos2008).

According to our informants, two factors played a role in this decision. First, the government disposing of a majority of seats was an opportunity to pass reforms more easily (P2). Second, the willingness of Socrates and of his health minister to reform pharmacies came from their perception that the ANF was misusing its privileged position and the fact that they knew that this perception was widely shared in Portuguese society (P2, P3, P5, P7, P9). For example, a former minister explained: “Pharmacies are too powerful, before the troika they made huge amounts of profit, that is not right in such a small country, we felt we had to do something” (P2). Another said: “ANF is a very powerful lobby, often obstructing public interests, with huge financial means (…) the state is captured by them, we had to put an end to it (P5).” A previous government official even said: “ANF, I hate them, they are a real mafia, we had to decrease their privileges, they made no sense and go against the government’s interest (P3).”

Even within the ANF, there is acknowledgement that those actions resulted from their being perceived, in their view inaccurately, as an organization that uses its power to only benefit its members and that does not sufficiently pursue the public good (P8).

The Socialist government passed Decree-Law nº 134/2005, which liberalized the sales of several OTCs. While this was of small financial consequence for pharmacies, it was still a defeat for the ANF, which had opposed the measure. A further initiative of the Socialist government was the reduction in pharmacy ownership restrictions (Decree Law nº 307/2007), again virulently opposed by pharmacists and the ANF. Following this reform, ownership of pharmacies is no longer reserved to pharmacists, as individuals and companies are now allowed to own retail pharmacies. This was another defeat for pharmacists, albeit again a limited one, as opening a pharmacy still requires satisfying criteria regarding proximity to other pharmacies and population density, thus limiting competition (P9).

In 2007, the government also reduced the pharmacies’ profit margins. This could have significantly hurt pharmacists, but in 2008 Correia de Campos lost his position in a government reshuffle, and in 2010 the profit margins were changed back to their pre-2007 level. Police wiretaps in the context of a broader corruption investigation involving Sócrates later revealed that the ANF’s director and a Socialist Member of Parliament had pressured persons who had direct contact to Sócrates so that the latter would convince the Secretary of State Francisco Ramos to stop blocking the profit margin decree. This led to formal charges of traffic of influence against the ANF. While these were eventually shelved, they further damaged the association’s reputation.

In May 2011, the Socialist government and the main center-right opposition party signed the EAP with the Troika, which mandated several measures aimed at reducing pharmaceutical expenditures. These measures had been discussed by several previous governments but could not be passed because of the resistance of manufacturers and pharmacies. Policymakers in government, of both the left and the right, saw the EAP as an opportunity to impose reform (Asensio and Popic Reference Asensio and Popic2019) (Moury and et al. Reference Moury, Ladi, Cardoso and Gago2021) (P1, P5, P6, P7). As an informant explained about the reforms regarding the pharmaceutical sector: “Most of the measures had been proposed by the government itself… There is a window of opportunity here that (…) allows reforms to be carried out, reforms that had been very strongly resisted by stakeholders, professions, industries, pharmacies, the administration itself” (P7). Another said: “Portugal had the highest per capita spending on medicines in Europe – something wrong in a country with a relatively low GDP (…) we all knew something had to be done; but we could not pass reforms, doctors opposed them, the industry was blocking them … We asked to have this measure inserted in the memorandum” (cited in Moury and et al. Reference Moury, Ladi, Cardoso and Gago2021, 95).

Two further measures included in the EAP were successfully implemented by the center-right government that followed the Socialist government in 2012. First, the rules governing international price referencing were revised, which reduced their price by changing the reference countries used for pricing prescription drugs. As pharmacists receive a margin on this price, this effectively reduced their profits. The second measure was the move from margins being set across the board to regressive margins, which reduced the overall margin (Pita Barros Reference Pita Barros2012).

The measures adopted during the Troika period resulted in a 14% price decrease on average, and even more for generic drugs (Pita Barros Reference Pita Barros2012). The significant negative impact on pharmacies of price and reductions led to concerns about the financial sustainability of smaller pharmacies (Pita Barros Reference Pita Barros2012). While some services were outsourced by hospitals to pharmacies to partially compensate for the lost revenues (P10), the subsequent governments have not reversed any of the measures on pharmacies’ regulation and profit margins.

In sum, the very poor sociopolitical reputation of the ANF has meant that, despite the vast array of material resources at its disposal, the association has been unable to mount an effective opposition to the reforms.

Greece

The Greek case tells a very different story compared to the Portuguese case. Pharmacies’ contribution to society derives from the close relationship between pharmacists and the public in Greece. This relationship has developed through the informal provision of services such as health and medication advice, checking blood pressure and other simple medical checks, help with injections, first aid, and first point of reference for domestic violence since the COVID-19 crisis erupted. All these services are provided for free. While pharmacies are also an integral part of the Greek health system for the provision of prescription drugs, they are valued by the citizens mainly because their services are easy to access in comparison to the cumbersome processes of accessing the national health system (G6, G8).

Pharmacies in Greece are represented by the PPA, which is responsible for essential tasks such as the profession’s code of conduct and disciplinary matters. PPA was established in 1928 and is a legal entity under public law (Law 3601/28). It is also a key stakeholder during the adoption of new legislation for the pharmaceutical sector and is active in representing the profession’s interests. It is an umbrella organization for 54 local pharmacists’ associations, such as the influential Attica Pharmacists’ Association representing pharmacies in Athens and the region of Attica. All pharmacies are required by law to become members of the PPA when they receive their license, meaning that the PPA represents 100% of pharmacies in Greece. PPA is well-resourced with administrative staff (8–10 people) and a large budget that allows for the funding of campaigns and for the support of its members. Regarding their struggle against the EAP’s reforms, one of its leaders explained that “We caused an organised, systemic and well-funded damage with significant political cost as well as an institutional war at the Courts and we approached other political parties such as SYRIZA” (G1). Its key source of funding is member subscriptions (G1). PPA used to advance prescription expenses to pharmacies while these waited for the reimbursement from small insurance funds, but this is no longer the case after these funds were merged in 2016 (www.efka.gov.gr, accessed 17/05/21).

In a context in which access to public health services is cumbersome and uneven, pharmacies are seen as an integral part of the community’s public health environment and their reputation among policymakers is neutral if not positive. Deriving from the pharmacies’ reputation, the reputation of the pharmacists’ association is also better than that of many other interest groups or trade unions (G2, G3). A search of important daily and Sunday newspapers (Kathimerini, To Vima, Avgi) between 2005 and 2019 found only eight articles reporting about the reforms in pharmacies. No opinion articles in favor or against the reforms were found. The Hellenic Competition Commission in its opinion on the draft law for the opening of the professions published in 2011 as a response to the first EAP does not make any concrete reference to pharmacists. Footnote 5 This lack of discussion shows that the reform of the pharmacies’ regulatory environment was not a salient issue before or during the crisis. Nor was it an issue that created major conflict and counter-lobbying. It was mainly an issue between the respective government testing the possibility of pushing forward the EAPs conditionality and the PPA.

The liberalization of pharmacies was not on the agenda before the financial crisis hit Greece. The country’s three EAPs (2010, 2012, 2015) all included commitments to liberalize the professions. PPA was invited by the Ministers in charge of pharmacies’ liberalization to discuss the coming changes before the signing of the EAPs, but these meetings were often formal and without much substance given the rushed nature of the negotiations (G1, G2). Greek governments, however, were desultory in reforming the pharmacy sector. As a key policy advisor put it: “The Greek side did not believe in the liberalization of pharmacies in particular – not of other professions – but of pharmacies in particular” (G2).

PPA is traditionally close to center-right New Democracy (in government with the Socialist party between 2012 and 2015 and alone since 2019), and the party has been reluctant to disappoint it. A key political advisor to the 2012–2015 government said, “when it comes to pharmacies, we believed that most of their claims were just” (G2). Although right-wing politicians recognized the need for reform and modernization of the pharmacies’ regulatory environment, they often describe the reforms introduced in the three EAPs as hasty and poorly designed (G2, G5).

The left-wing SYRIZA also did not want to disappoint the pharmacies since they are rooted in the community, and they were seen as one more hub for grass-root resistance to the EAPs. A SYRIZA MP explained: “This market cannot function in the classic neoliberal way that believes that the market will be self-regulating. This market cannot be self-regulating. Rules are necessary to protect the public health and public interest” (G3). Thus, the SYRIZA government (2015–2019) went even further than New Democracy in halting or even reversing reforms (G1, G2, G3). The SYRIZA MP continued “we did not benefit politically but there was a feeling that we protected the interests of pharmacists, we did not allow for a liberalization that they were afraid would lead to an oligopolistic transformation” (G3). The PPA felt free to lobby both parties against the reforms since it sees its role as representing the profession’s interests and does not consider itself to be closely connected with any party (G1). This lobbying took place via media campaigns, protests, and even a few strikes especially during the first two EAPs. These public forms of opposition were seen as necessary by the PPA given the uncertainty of the time and the pressure put upon the Greek government by the Troika during this period. Many sectors were being reformed and several professions were liberalized (Stolfi and Papamakriou Reference Stolfi and Papamakriou2019). No profession or occupation could feel safe regardless of its reputation or indeed need to reform (G1, G6).

The one reform to be fully implemented targeted pharmacies’ profit margins. Before the 2010 crisis, profit margins in Greece were among the highest in the OECD, set at 35% for most drugs (Yfantopoulos Reference Yfantopoulos2008). This increased public pharmaceutical spending as most drugs were distributed through pharmacies. A reduction by 5% in profit margins and the channeling of high-cost drugs through hospitals and the National Organization for the Provision of Health Services (EOPY) occurred in 2013 (Law 4213/2013, G1, G2). Neither PPA’s positive reputation nor its resources could halt this reform since it was about cost-cutting, which was the key priority for the Troika during the crisis (Moury and et al. Reference Moury, Ladi, Cardoso and Gago2021). However, recent legislation under the current New Democracy government has reintroduced the distribution of some high-cost drugs by pharmacies (Law 4655/2020).

Conversely, all structural reforms that could negatively affect pharmacies’ business model were successfully resisted by the PPA. Legislation about the minimum distance between pharmacies and population criteria has been in place since 1991 to avoid the overconcentration of pharmacies in urban areas and the lack of services in remote areas (Law 1963/1991) (Dagres Reference Dagres2019). An attempt was made in 2014, in response to the conditionality of the second EAP (2012), to lift geographical restrictions and to increase competition, but PPA opposed it and eventually it was not implemented (Law 4254/2014, G1).

Another unsuccessful reform concerned the liberalization of pharmacies’ opening hours. Following the first and second EAP, new legislation initially extended opening hours (Law 3918/2011) and then fully liberalized them (Law 4254/2014). Both laws caused a backlash from the PPA and regional authorities. These actors feared that these laws would favor larger pharmacies to the detriment of smaller ones and that the extended/flexible hours would reduce the number of pharmacies offering overnight services, thus jeopardizing the stability of the network and public access to pharmacies (Dagres Reference Dagres2019). Law 4517/2018, introduced by the SYRIZA government and based on PPA’s suggestions, attempted to correct the serious distortions caused by the extended/flexible opening hours regimes by adding certain safety valves. This effectively killed the reform although some flexibility in the opening hours of pharmacies has been introduced (G3).

Changing the ownership status of pharmacies by allowing non-pharmacists to establish new pharmacies through a Limited Liability Company was also attempted (Joint Ministerial Decision 36277/2016). However, after PPA mobilized against it, the Council of State judged it unconstitutional and the status quo ante was restored, with very few exemptions for non-pharmacist licenses (Law 4509/2017). In any case, the market was already saturated and difficult to navigate for foreign companies and there was not much interest in investing in the sector (G1, G2, G3).

Liberalizing the price and points of sale for OTC drugs was another failure. Before the crisis, OTCs were only available through pharmacies. In 2012, partial liberalization of OTCs meant that supermarkets were allowed to sell some OTCs. Opposition by pharmacists was fierce, claiming public health reasons and because OTCs are a key source of pharmacies’ profits, which had already been reduced. The SYRIZA government reduced the ability of supermarkets to sell OTCs by creating a new category called Drugs of General Distribution which meant that fewer drugs could be sold outside of pharmacies (Law 4389/2016, G3).

In conclusion, a positive or at least neutral reputation meant that the PPA was not hampered in its efforts to deploy its resources (membership, information position in the political system, access to political parties, and mobilization) to successfully oppose the implementation of most structural reforms included in the EAPs. The pharmacies liberalization never became salient or caused major conflict between parties or other lobbies. As a former member of government put it: “At the end many of the regulations, also with the tolerance of State institutions, were watered down and thus the impact they might have had on consumers was minimised” (G4).

Discussion

Table 3 summarizes our assessment of the evidence presented in the previous section. As our empirical cases show, the resources of the Portuguese pharmaceutical association were greater than those of its Greek counterpart. At the same time, exogenous reform pressure was higher in Greece than in Portugal because of the greater depth and length of the Greek crisis. This should have led to more damaging reforms to the pharmacists’ established interests in Portugal than in Greece.

Table 3. Sociopolitical reputation and pharmacy reforms in Greece and Portugal

However, this has not been so. In the period under study (2005–2021), four measures were introduced (and maintained) in Portugal that negatively affected pharmacists: the liberalization of OTC sales (2005), the partial liberalization of ownership (2007), the reduction in profit margins through the introduction of regressive margins (2012), and the changes to the international price referencing (2012). These outcomes contrast with the Greek case, where only one major reform was passed that was not later withdrawn, the 2013 reduction of profit margins.

The difference between these two cases can be explained by the sociopolitical reputation of pharmacies and their associations. Combining interviews with public officials and an additional proxy of sociopolitical reputation (the scope of free health services offered by pharmacies), we show the sociopolitical reputation of pharmacists and their association was very negative in Portugal and neutral, if not positive, in Greece. Moreover, the gulf in reputation between the two cases reassures us that the difference in the true values of this variable in the two cases is unlikely to be entirely due to the inevitable problems of measuring and comparing actor reputations across different countries (Adcock and Collier Reference Adcock and Collier2001; Bustos Reference Bustos2021).

The two cases illustrate the link between interest group sociopolitical reputation and the extent to which policymakers are willing to push policy changes the group opposes. In the case of Portugal, policymakers introduced reforms to limit the power of the ANF even before the financial crisis, since it was behaving unethically. In the case of Greece, policymakers were more inclined to listen to the PPA since they trusted it and considered its demands legitimate.

Additionally, the variation in sociopolitical reputation fits not only with the variation in reform outputs in the two countries but also with the different salience of the reforms in the two countries. The media reported on the privileges of pharmacists and excessive power of their organization much more expansively in Portugal than in Greece, where the issue of pharmacies and of their privileges had never been salient – thus further decreasing governments’ willingness to reform the sector. By contrast, both countries were similar regarding conflict: as reforms only generated costs for the pharmacists and diffuse benefits for the population, there was no lobbying by other interest groups in support of reforms.

Conclusions

Portuguese pharmacies have suffered several setbacks over the past 20 years. Their activities were partially deregulated in 2005 and 2007; later their profit margin was cut during the implementation of the EAP that the country entered into following the 2010 financial crisis. By contrast, Greek pharmacists were able to stop most reforms negatively affecting them at a time when Greece was under severe international pressure to introduce structural reforms, including reforms of the pharmacy sector. This is puzzling since the Portuguese pharmacists’ association had more resources available than its Greek counterpart and Portugal was under international pressure to reform for a shorter time than Greece.

We have explained the divergent reform outcomes in Greece and Portugal through the very different sociopolitical reputations of pharmacists and their associations in the two countries and argued that therefore the concept of sociopolitical reputation should take its place alongside exchange resources to the conceptual toolbox of scholars studying interest groups’ influence.

Building on the literature on bureaucratic and especially corporate reputation, we have defined an interest group’s sociopolitical reputation as reputation for behaving in an ethical manner and contributing to socially sanctioned goals. Such reputation derives from a group’s past and current behavior and from how relevant audiences perceive it.

In the case of Portugal, policymakers see pharmacists and their association in a very negative light, and this has motivated their move to reform the sector well before structural reforms were included in the country’s EAP; when they committed to it, policymakers of both the left and the right even used the external imposition of structural reforms as a window of opportunity for pharmacy reforms that they had planned all along. Conversely, in Greece pharmacists and the pharmacists’ association enjoy a neutral if not positive sociopolitical reputation with policymakers. Governments of both the left and the right showed no inclination to reform the sector during, let alone before, the country’s bailouts and did the bare minimum under pressure from Greece’s international creditors.

The concept of interest groups’ sociopolitical reputation adds a new dimension to the recent research on interest groups and democratic representation. This work is concerned with whether and how interest groups help convey societal preferences (Boräng et al. Reference Boräng, Naurin and Polk2023; Flöthe and Rasmussen Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019; Klüver and Pickup Reference Klüver and Pickup2019), including whether interest groups that are aligned with citizens’ preferences are more influential than those that are not (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018).

A key question for further research regards the conditions under which positive or negative sociopolitical reputation affects an actor’s influence. Our work, in line with the research on corporate reputation, points to the impact on business influence of a positive public image, and it shows that power which is perceive as “excessive” and leading to too many privileges can backfire against a given group. However, sociopolitical reputation is only one of the resources at the disposal of interest groups. Interest groups with a bad sociopolitical reputation but with otherwise strong instrumental resources might be able to resist reforms hurting their interests (think for example about the gun lobby in the USA). Moreover, the literature on the structural sources of business power suggests that actors can be influential even if they do not engage in activities to influence policymakers (Busemeyer and Thelen Reference Busemeyer and Thelen2020; Culpepper Reference Culpepper2015; Dowding Reference Dowding2021). Consequently, a negative public image may not be enough to trigger efforts to influence policy.

Our intuition is then that sociopolitical reputation matters most for liberal professions. First, their identity and economic claims rest on the societal belief that they serve the public good (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Hardin and Levi2005, 110–113; Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2016). Second, professions do not enjoy the structural power of actors such as big business.

In closing, however, we should stress that even relatively small-size interests have combined bad press and outsize influence on policymakers, taxi owners, and beach concessionaires in Italy being a case in point (Kazmin Reference Kazmin2022; Kazmin and Sciorilli Borelli Reference Kazmin and Silvia2022). Conversely, powerful businesses like “big pharma” in the USA have recently seen their interests hurt by the Biden administration after the opioid crisis and the public’s awareness of their role in creating it, weakened their sociopolitical reputation. These cases suggest further avenues for research on how and under what conditions sociopolitical reputation matters. Thus, future work on the ability of firms and professions to influence or resist reforms should analyze how sociopolitical reputation interacts with the broader institutional context of the state (Steinmo and Watts 1995) and governing political parties (Pritoni Reference Pritoni2019).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X23000363

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the inteviewees for their time and valuable information they provided and the anonymous referees for their sharp comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank Laura Chaques Bonafont and Gregoris Ioannou for initial discussion on the article as well as Dimitra Panagiotatou for acting as a Research Assistant for the Greek case.