A. Introduction—Is European Law European?Footnote 1

The European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) is usually understood as being meant to create a uniform standard of human rights in the contracting states, based on legal and political principles which supposedly transcend national borders. In the scholarship of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), this premise of a unified practice of the application of the Convention has largely been taken for granted. For example, this approach is apparent in the standard textbook on the topic, which is usually structured around chapters on each of the substantial right articles of the Convention, treating each of those as one unified theme of laying out the practice of the ECtHR.

However, as Anthea Roberts has recently pointed to in her seminal work, Is International Law International?, legal systems are rarely as coherent as they appear in doctrinal textbooks.Footnote 2 Roberts argues that the perceived unity of international law is in fact composed of several more or less intertwined sub-fields of conceptions about what international law is. Roberts’ scholarship builds on enduring debates about universalism and particularism in international law. Public international law is generally conceived as a unified system that is equally binding on states and entities.Footnote 3 The regionalism of international law through international courts challenges this narrative.Footnote 4 While Roberts deals less with the practical application of international law, she maps the international legal scholarship and shows how there are, in fact, several international legal scholarships living in different degrees of isolation from each other. Contrary to the underlying assumption of the singular coherence of international law, Roberts suggests that we must understand international law as a heterogeneous object.

Taking inspiration from the rhetorical title of Anthea Roberts’ seminal work, we ask in this article the question of whether European law is in fact European, examining whether we should look at the practice of the ECtHR as a practice in the singular, or to a larger extent understand it as practices in the plural. Our approach differs, however, in two substantial ways. One is jurisdictional. Whereas Roberts focuses on general international law and does so globally, we focus more narrowly on human rights law as it is produced by the ECtHR.Footnote 5 Another relates to source material. Where Roberts has the academic community of international lawyers and their textbooks as her object of study, we focus on case law—the rulings of a single international, European, court. Our study thus touches upon an area which Roberts engages less in—namely legal practice itself.Footnote 6 For one, the global academic community of international law is differentiated between domestic or regional traditions, but is international legal practice itself also differentiated?

We approach this question by looking at the way the ECtHR uses its own case law in its citations to former judgments, and in line with recent scholarship on the topic, we use these patterns of citations as proxies for underlying legal content that we then validate qualitatively. As such, we seek to investigate a possible stratification of the Court’s practice from two different angles—the first is to look for a general tendency for the Court to cite earlier cases against the same state as the one which is respondent in the present case. The second is to look for more specific examples of practice, which are bound to and by the national context in which they are applied over several generations of cases. Our aim is to inquire into whether and how part of the case law of the ECtHR is closely tied to specific social situations in individual member states, thereby, to some extent leaving some strands of the ECtHR’s case law relevant only to those member states. We discuss whether this could be seen as an example of what we term “soft legal pluralism”.

In Section B, we set out to identify a theoretical position between strong pluralism, as defined by John Griffiths, and legal centralism, as defined by those including Hans Kelsen and Ronald Dworkin. We call this soft legal pluralism. Within this theoretical framework we outline a typology of two types of precedent which we in turn use to identify the legal stratification in question. In Section C, we demonstrate a general tendency for the Court to over-cite cases against the respondent state. In Section D, we explore the legal characteristics of these state-bound clusters of case law. In Section E, we discuss two different approaches to explaining the declining trend of same state citation.

B. Domestic Particularity—A Form of Legal Pluralism?

I. Forms of Legal Pluralism

Traditionally, the concept of legal pluralism refers to a situation where competing legal systems find application in the same context. By way of definition, Griffiths in his much-cited article on the topic, conceptualizes legal pluralism as “that state of affairs, for any social field, in which behavior pursuant to more than one legal order occurs.”Footnote 7 In this vein, Tamanaha refers to the relationship between canonical and secular law in the European Middle Ages, or local customary law and British colonial law in India as examples of this.Footnote 8 Stone Sweet uses the concept to describe the relation between national and European constitutionalism in the member states of the European Union.Footnote 9 These are what Griffiths would characterize as “weak legal pluralisms,” in the sense that the co-existence of more than one legal system is sanctioned by the state, and thus not “ontologically excluded by the ideology of legal centralism.”Footnote 10 Griffiths turns to the strong form of legal pluralism on the other hand as an ontological question; empirically observing competing normative orders in which the very co-existence defies the traditional ideology of legal centralism—as found par excellence in the works of scholars such as Kelsen, Dworkin, and others:

Legal pluralism is an attribute of a social field and not of ‘law’ or of a ‘legal system’. A descriptive theory of legal pluralism deals with the fact that within any given field, law of various provenance may be operative. It is when in a social field more than one source of ‘law’, more than one ‘legal order’, is observable, that the social order of that field can be said to exhibit legal pluralism.Footnote 11

We do not adopt this strong concept of legal pluralism. Instead we seek what might be described as soft legal pluralism: A midway position between strong legal pluralism and centralized monism. Therefore, in this article, we investigate to which extent the “legal centralist” understanding of the practice of the ECtHR as one coherent whole, covering all the treaty states under one unified and normative framework, is compatible with our empirical findings. We seek to explore to what extent the case law of the ECtHR, is to a greater or lesser extent, divided into sub-practices which do not easily generalize to a coherent, overarching, normative whole.Footnote 12

The idea that the ECtHR’s practice is divided into a number of sub-practices will not be wholly unfamiliar from a doctrinal standpoint. The ECtHR has developed its “margin of appreciation” practice in part to allow for heterogeneity across member states in regards to how they fulfill their obligations under the Convention.Footnote 13 This means that member states may have differing standards on say, prison conditions, defamation, or religious neutrality in public institutions, all while acting in conformity with the Convention. Our approach differs however with this scenario, because we do not focus on margin case law, but instead on case law that is characterized by its orientation towards specific member states by virtue of its citation patterns. While margin case law can easily fit into a homogenous coherent narrative, the case law that is directed towards a specific state because of its citation patterns cannot be explained by this doctrine and therefore represents a different subset of cases that have not previously been accounted for in the literature.

Therefore, we propose a reading of the Court’s practice that is open for a more diverse understanding, entailing that not all case law can be summarized under the heading of the practice of the ECtHR, but must instead be described as the practices of the ECtHR.

II. Why Plurality in the Practice of the ECtHR?

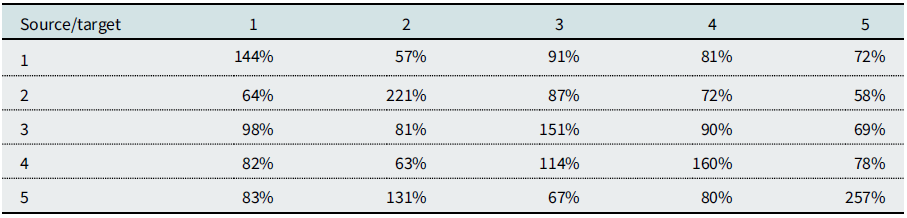

We find good reasons why we could expect to find this phenomenon at the ECtHR, both originating in the massive expansion of the Court’s jurisdiction following the end of the Cold War and the ensuing reorganization of the Court. Spurred on by the increase in caseload, the Court was reorganized in 1998 with Protocol 11 from a Chamber-Grand Chamber system to a structure of four, later to become five, semi-permanent sections, overarched by the Grand Chamber. Because each case is sent to the section in which the judge from the respondent state sits, one could expect that a certain expertise and knowledge about each state could begin to build into the individual bureaucracies of the sections.Footnote 14 Registry lawyers are assigned to sections of the registry based on their knowledge of local laws and languages. The registry lawyers would naturally look at their own back-catalogue of judgments with which they are more familiar than they are with those of the other sections. Simultaneously, they would possess greater knowledge about the national legal context within which the Convention is supposed to take effect. Given time, this could mean that increasingly differentiated patterns of precedent—observable, in our approach, from differentiation in citation patterns—could potentially lead to a differentiation in the way the Convention is applied. While the Grand Chamber is hierarchically superior to the Chambers for the purpose of unifying and directing the practice across the Chambers, the amount of cases not heard by the Grand Chamber is immense. The harmonization and homogenization of case law that is supposed to take place through Grand Chamber rulings therefore, we estimate, will not completely cover all aspects of the Court’s case law. We find support for this assumption in Table 1. The table is built on all citations between judgments from sections—for example, excluding all pre-Protocol 11 cases and all Grand Chamber cases. The percentage shows how often a judgment from a section—rows—cites a case from itself or other sections—columns—taking into account the amount of citations the receiving section gets overall.Footnote 15 Thus, the table shows a clear tendency for every section to cite its own cases more often than they cite cases decided by other sections.

Table 1. Citations between sections – Comparison between random and actual percentile distribution

Needless to say, because judges do rotate between the sections, this expected mechanism would have its limits. Yet, it might spur a tendency to build semi-isolated clusters of legal practice based on national specific contexts. This explanation is mostly external to the law, focusing on the organizational structure responsible for writing the judgments instead of the legal content of the cases themselves as the cause for the way the Court builds its network of citations. Another explanation focuses on a different aspect of the expansion of the Court’s jurisdiction.

In the first years of the Council of Europe, the member states were predominantly Western European, NATO-aligned, or at least neutral, and with few exceptions—like the Regime of the Colonels in Greece, which also opted out of the Convention for almost ten years until parliamentary democracy was reinstalled. All followed political and governmental models that were in many regards quite similar to each other, even if there were also differences relevant to human rights—this is also pointed out above in relation to the role of margin of appreciation. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, the composition in member states changed dramatically. In just ten years from 1989 to 1999, seventeen new states which were either former Soviet republics, members of the Warsaw Pact or parts of Yugoslavia joined the Council of Europe; a few more entering after the turn of the millennium.

Today, the Court holds jurisdiction over forty-seven member states with very different histories, social structures, and political systems. Just to mention the most obvious, the difference in historical background for states that where members of NATO during the Cold War and states that were members of the Warsaw Pact has large implications for the type of human rights policies, or lack thereof, pursued by each state. Without diminishing the relative differences between the earlier treaty partners, we consider it safe to say that the more recently included states add significantly to the number of different factual situations the Court has to adjudicate upon.

With this widening of jurisdictional scope to include member states with widely differing legal and governmental traditions, it would not be surprising to find that the Court’s jurisprudence would need to deal with quite diverse issues emerging from the plurality of social and governmental traditions and practices. Thus, we expect that the Court would have to deal with this plurality to a certain extent, by directing some of its case law to quite specific issues in national contexts.

Our approach should be seen as supplementing earlier network analysis studies on case citations of case law by the ECtHR. In 2011, Lupu and VoetenFootnote 16 examined the question of why and how the Court justifies its judgments with citations to its own case law. As part of this study, the authors constructed a network of the Court’s case law citations and tested a number of hypotheses against the structure of the citation network. One of their findings was that:

…[N]ational characteristics of respondent governments do not explain why some decisions rely more on citations to precedent than others. This is a key indication that the Court chooses the precedents it cites based on the legal issues in the case, regardless of where those cases originated. The one exception to this is that cases against respondent governments with common law origins appear to be more embedded in case precedent than cases originating in states with certain other legal traditions, perhaps because common law courts are more used to this practice.Footnote 17

It is hardly surprising that “legal issue” is more important than the “national characteristics of respondent governments.” The Court’s decisions derive from complaints that the Convention has been violated in some way. Arguments for the existence of such violation always revolves around a specific issue that in turn relates to a specific rights provision in the Convention. Assuming that a case revolves around the right to freedom of expression, it makes less sense for the Court to cite previous cases about—for instance—the right to a fair trial simply because those previous cases were directed to the same respondent state. A previous case about the right to freedom of expression will be more relevant to cite, even though it might involve another respondent state. Therefore, Lupu and Voeten’s finding that national characteristics of respondent governments do not explain citations—only hold if one disregards legal issue. In our view, it is misleading to take such a generalized view of the role of the national characteristic of the respondent government; it only makes sense to view this role within the case law on specific rights provisions. Moreover, Lupu and Voeten do not measure state-by-state to what extent the Court cites previous case law against the same state. Instead they rely on an average across all states. Contrary to Lupu and Voeten, our approach suggests that citations to cases against the same state do play a role in the Court’s practice. Further, Lupu and Voeten do not discuss who specifically embeds the citations in judgments. For example, they do not consider how the judgements under analysis are produced. The strategic legitimization approach of Lupu and Voeten is characterized by looking at the judgment texts as a means of acquiring a certain end—for example, the legitimacy of the deciding court. This is an approach often found in American-style scholarship on international law. Even when legal issues in themselves are also taken into account,Footnote 18 the focus of the strategic legitimization theory is on the part of the writing—for instance, citing precedent—which, according to the theory, is directed to an outside audience and as a reaction to extra-legal circumstances.Footnote 19 This external approach often faces an interiority problem—it assigns a narrative to practice without the empirical resources to back it up. External assumptions about case law tend to neglect the more internal workings of a court.

Without rejecting the external perspective all together, our approach focuses instead on the internal aspect of the law, meaning that we try to make sense of the Court’s use of precedent as part of a legal reasoning in and of itself. In doing so we presume decisions to be part of the rationalization process, where the court reconstructs the law in order to reach a well-argued decision. The philosophical basis for this construction can be found, for instance, in European style legal reasoning, which emphasizes the role of rational discourse and coherence as criteria of legal validity.Footnote 20 It can be seen, furthermore, in the principal textbooks of the ECtHR, which represent the Court’s case law as if it were a coherent whole.Footnote 21 The Court itself has also gone down a path of institutional rationalization through a series of reform protocols which have aimed to improve the functioning of the ECHR system in response to its overburdened docket.Footnote 22

The findings of this article, we think, indicate that the Court is forced to rule in cases where the domestic legal and factual circumstances cannot convincingly be subsumed under any overarching strategy or principle, which, in turn, leads the Court to develop a more “local” approach to its legal argumentation. This approach respects that “the pragmatic effects of the ECHR only deploy at the national levels,”Footnote 23 and is therefore more closely aligned, and ultimately aimed at the local conditions that exist within the specific member state in question. This finding not only coheres with the ECtHR doctrine of subsidiarity, but also with the overall framework of the ECHR legal order.

III. Two Kinds of Precedent

Building on the above considerations, we introduce a distinction between two types of precedent in the practice of the ECtHR: first, treaty-applying precedent, and second, context-specific precedent. We will use this typology to single out the context-specific precedent that we expect are driving the national specific clusters of case law. Before clarifying this further, we will briefly explain our use of the word “precedent.”Footnote 24 We understand precedent as elements of the Court’s case law that not only sets out some principle of law or another, but that the Court also subsequently uses to justify and legitimize later judgments. More specifically, we operationalize this by looking at the number of times the Court itself refers back to a particular judgment and/or a specific paragraph. With all the possible objections against this method,Footnote 25 we generally see it as a sound approach in the context of large sets of interrelated judgments.Footnote 26

In the first category, the treaty-applying precedent, we find precedent that lay out general principles of interpretation of the treaty, which, owing to their general formulations of method and concepts, would make them applicable to—almost—any situation that falls under the material substance of the treaty provision. An example of this can be found in Association Ekin v. France, in which the Court notes about the concept of necessity that:

[T]he necessity for any restrictions must be convincingly established. The adjective “necessary”, within the meaning of Article 10 § 2, implies the existence of a “pressing social need.” The Contracting States have a certain margin of appreciation in assessing whether such a need exists, but it goes hand in hand with European supervision, embracing both the legislation and the decisions applying it, even those given by an independent court. The Court is therefore empowered to give the final ruling on whether a “restriction” is reconcilable with freedom of expression as protected by Article 10….Footnote 27

The examples of the Court reiterating its consolidated case law in this manner are numerous, and most people familiar with European human rights law will immediately recognize not only the content, but also the wording, which is often copied in these kinds of precedent.Footnote 28 While paragraphs containing these formulas are often well-cited, it is not always clear how they contribute to the concrete solving of a case, because they mostly lay out a method or approach to how the treaty provision is generally to be interpreted.

The second category in our typology is the context-specific precedents. These are cases where the Court applies the Convention with respect to not only the specific facts of the case, or in overall terms of Convention interpretation, but also with respect to circumstances such as national legislation in force, the political history of the concerned area and time, certain developments within the respondent state, etc. To give an example, in Dobrev v. Bulgaria,Footnote 29 the Court first recapped some changes in national criminal law and then proceeded to note how “divergent interpretations of the above provisions were observed in the initial period of their application upon their entry into force …. ”Footnote 30 This observation about the development of interpretation of the Bulgarian penal code has been used by the Court in a number of subsequent cases against Bulgaria, and notably—but not surprisingly—not a single time against another state.

Is this not just a distinction of law and fact rather than one of two different types of precedent? Recall here that we define precedent value mathematically, as the number of times a specific passage in a case has been cited by a subsequent case. From this perspective, understanding a text passage as precedent does not rely on its interpretability but on its active use by the Court. In this sense, our study uses an empirically operational approach to precedent as opposed to an analytical approach. Consequently, we do not operationalize an a priori definition of precedent, but treat the Court’s active use of citations as signs of precedent.

The purpose of our distinction between two classes of citation—precedent—is to isolate the context-specific precedent in which the Court builds its argumentation on circumstances that cannot easily be transferred to a case pertaining to the same Convention Article in a different context. This is the type of precedent that we expect to see developing following the period after the expansion of the Court’s jurisdiction. The degree to which this type of precedent can be identified will therefore be essential to evaluating to what extent and how the Court handles state specific conditions in their case law.

C. State Driven Over-Citation

In this section, we seek to point out a general tendency in the Court’s practice to use as precedent cases against the same state that it is adjudicating in the case at hand. When the Court is over-citing a specific group of judgments based on the parameter of the respondent state, we dub this phenomenon as state-driven over-citation. Drawing on the methods from previous research in citation network analysis of the Court’s practice, we argue two main points. One is the rather simple point that the Court generally uses precedent from cases against the same state that it is currently adjudicating against to a higher degree than what a random distribution would suggest. Digging further into this, we also argue that this general tendency is split between states, where the practice against some states has more instances of nationally isolated citations than is the case for other states.

By studying the citation patterns between judgments and the paragraphs they cite from other judgments, we find that, overall and historically, the sections of the Court have cited paragraphs from cases concerning the same state as the one before it in the citing case (same state citation) more than they would have if the citations were randomly distributed between treaty states.Footnote 31 Overall, this over-citing tendency has decreased in recent years, but an investigation of the citation patterns concerning individual states reveals that this tendency is not uniform.Footnote 32 Additionally, the over-citation trend appears to be driven by a few states, namely Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine, while other states have an even distribution, and some a lower distribution than expected.Footnote 33 We conclude that this indicates that the Court might have disparate legal practices according to which respondent state is standing in front of it.Footnote 34 We consider our finding to be robust,Footnote 35 and the same state citation rate remains high when compared to that of a different court, like the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS).Footnote 36

We conclude that a possible explanation for our findings can be found within the internal point of view of the facts and law in each individual case, rather than in external factors such as political strategy.Footnote 37 Examples of this are explored in Section D, while Section E seeks to examine why there has been a general decrease in same state citation.

I. Construction and Selection of Data

Our data is a case-to-paragraph network of citations in the practice of the ECtHR. This means that we have extracted all judgments from the Court’s own database, HUDOC, and again from these, extracted all references to the Court’s case law on paragraph-level. When the citations go to a group of paragraphs in one go, one citation for each paragraph mentioned is registered. Because we wanted to focus on the effects of the implementation of Protocol 11, we removed all cases that were not decided by a Chamber under the organizational scheme of the Protocol. Consequently, the network would also only include citations between two Chamber judgments.Footnote 38 This gives us a sparse network of 48,791 citations from 5,399 cases to 20,748 different paragraphs. After exploring the network from a Chamber-perspective,Footnote 39 we recognized that the respondent state of each judgment was a more informative feature regarding the divisions of the network.

From this state-oriented approach, we decided to further limit our analysis to cases against a smaller group of fifteen states. This is foremost because we want to focus the analysis and exposition on larger clusters of case law without blurring the results with forty-seven different figures for every step. Another reason was that we wanted to limit the amount of manual reading needed for the qualitative step in our inquiry while still getting a representative overview of the Court’s practice. We did this by selecting the top-three states with the most cases decided against them from each of the five sections. This gave us a large amount of cases and citation, as well as a variety of different states without getting too many different sub-networksFootnote 40 of cases against different states. This selection criteria led us to focus on Poland, Greece, Italy, Slovenia, Moldova, Turkey, Portugal, Russia, Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, Hungary, Ukraine, France, and Bulgaria. We singled out these states from the overall data set in a way such that cases and citations relating to other states were still a part of the network; meaning that they could still influence the centrality of the selected judgments.

II. Approach: Networks and Sub-Networks

Earlier studies of the citation network of the Court’s practice have, in different ways, sought to subdivide the overall network into smaller, more approachable parts, often based on modularity algorithms, and thus inducing from the network.Footnote 41 We take inspiration from a slightly different, more deductive approach, which uses existing data about the cases to group them. In the same way as Olsen and Esmark has previously divided the Court’s case law into legal sub-networks based on classification of their main precedential function,Footnote 42 revealing so-called “polymorph precedents” that are cited for general principles of law, we divide the present dataset into sub-networks of different respondent states.

Here, we deviate somewhat from this earlier methodology in that we use a case-to-paragraph network instead of a case-to-case network and use the in-degree of paragraphs to measure their prominence within the overall network and sub-networks instead of pagerank.Footnote 43 Finally, instead of sub-networks based on articles, we arrange the nodes in sub-networks based on which respondent state the particular precedent concerns. The different construction of our network forces us to a somewhat more rudimentary approach to the data, because the one taken by Olsen and Esmark is based on the particular properties of pagerank score in a case-to-case network. We will elaborate on our method below.Footnote 44

III. Data Analysis

From our case-to-paragraph network, we can see that the Court cites cases against the same states more often than a random distribution suggests should occur. Figure 1 shows the proportion between citations going to a Chamber judgment against the same state and another state respectively. Two things are clear from the graph. First, at any point in time, the amount of state over-citation is significantly more than one would expect were the citations randomly distributed between the forty-seven treaty states. We elaborate on this by looking at the fifteen selected states in order to find out whether the over-citation is a uniform phenomenon across the network or not. Second, there is a decreasing tendency in the degree of state-citation. We will elaborate on this in Section E of the article.

Figure 1. Overall same state citation trend (all CoE states).

Behind the descending trend in the overall network is a slightly more nuanced picture when we look at the individual states. We want to illustrate this point in two ways. First, in Figure 2, we show the corresponding lines for just a few states which do not clearly follow the overall picture, compared to the lines for the fifteen states total and the overall network. For example, Russia stays on a stable ratio of around fifty percent, and Ukraine—after a steep drop in 2006—oscillates between somewhere over and under the trendline for all fifteen states. Our argument is not that there is a hidden counter-trend behind the trendline. Our argument is that there are significant nuances and differences between the different states. Some follow the overall picture, whereas others have different patterns in the way the Court cites cases against them. While it is outside the scope of this article to perform a detailed analysis of the fluctuations of each individual state, we find that this data gives indicia that there is some sort of variation in the citation patterns linked to variables of respondent state.

Figure 2. Same state citation trend (15 states & individual states).

Second, we want to show to what degree each cited paragraph is used by cases against the same state or against another one—the ratio of same state citations, in a case-to-paragraph network. We count two different in-degree values for all the paragraphs in cases against the fifteen states: one based on the number of citations the paragraph receives overall in our network of Chamber-judgments, and another based on the number of citations the paragraph receives from other cases against the same state—its own sub-network. We use the two values to calculate the proportion of the total citations each paragraph receives “from its own state;” a number that we use to determine whether it is cited solely or predominantly in cases against the same state, or whether the Court cites it in cases against a variety of states.

Subsequently, we remove all the paragraphs that have been cited less than three times total for two related reasons; the first being that we want to focus on paragraphs which have in fact been used actively by the Court as precedent on a more than just incidental basis.Footnote 45 The second is that all the sub-networks contain many paragraphs that are cited just once. These cases will receive a ratio-score of either one, if the single citation comes from the same sub-network, or zero, if not. When we plot the scores for each sub-network, these large groups of binary values, if not removed, would stretch the data away from the more floating scale we look for, and obscure the cases that are cited more times, scoring something in between zero and one.

Our last move at this stage is to calculate the proportion of total citations to paragraphs from each sub-network coming from itself. We calculated this based on the raw in-degree values instead of as an average of the ratio-scores mentioned above. The reasoning behind this is that we wanted the frequently cited paragraphs to weigh more in the calculation. This would not be the case if we used the decimals calculated for each judgment as the basis for the average, because a paragraph with a ratio of one-third would weigh less than a paragraph with a ratio of 100/300. Table 2 shows this ratio-score for each of the fifteen sub-networks in descending order, thus illustrating an overall ratio for the sub-network and not an average of the individual paragraphs comprising the sub-network. We can see that there is a large difference between the ways the Court uses precedent against each of the states. We added the same calculation for all of the fifteen states combined, marked in bold. Thus, the table shows that eighty-eight percent of all citations to judgments against Ukraine come from other cases against Ukraine, leaving only the remainder coming from cases against other member states. On the other end of the spectrum, only five percent of citations to cases against France come from other cases against France. Again, this table piles all citations together, and will not illuminate the spread on individual cases.

Table 2 Sub-networks ratio scores

As shown above, these average values can cover different compositions of citations. A sub-network of cases against the same state can contain both particular and broad cases spread evenly over the spectrum scoring from zero to one, or have two clusters of cases in each point of extremity—or endless other combinations. In this light, the average itself tells us little about how the citations are actually distributed. To show the spread better, Figure 3 contains boxplots of the score-distribution for each of the fifteen states. If the sub-network mostly contains paragraphs that are predominantly cited by cases against the same respondent state, Figure 3 will cluster them in the top of the plot, and viceversa. We can see from the plots that there is a remarkable difference in the way each sub-network is composed, approached from the perspective of ratio-scores. The tendency to over-cite cases against the same state seems to be driven mostly by Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine, whereas France, Italy, and smaller sub-networks such as Portugal and Romania all have lower ratios. Other states seem to have an even distribution—Poland and Turkey being some of the best examples. Combined with what we show in Figure 2, this supports a hypothesis that the overall descending trend, in regards to state-driven over-citation, obscures opposing tendencies when we break the data down in sub-networks.Footnote 46 By this, we mean that despite the general tendency, the Court seems to build disparate citation patterns against different states. This in turn implies that—based on our preliminary assumption that citation patterns might be a proxy for legal content—the Court might have disparate legal practices according to which respondent state is standing in front of it.

Figure 3. Box-plots score distribution.

1. Representativeness of the Same State Citation Rate

As shown in Figure 1, the rate of same state citation at the sections of the ECtHR has been fairly high, ranging from around eighty to seventy percent in the early 2000s and decreasing to around just above twenty percent in 2016. In order to ascertain whether this is truly representative of the citation practice at the sections, or due to outliers in the dataset, such as a judgment containing a particularly high amount of same state citations,Footnote 47 we conducted the following robustness check.

For each year in the 2000–2016 period, seventy-five percent of cases, with their accompanying citations, were randomlyFootnote 48 selected, and the rate of same state citation measured anew in order to check whether the same trend of same state citation was present. This test was conducted five times. By removing twenty-five percent of the cases, and repeating the test, we decrease the potential that the end result will be skewed by outlier cases.

The result of the robustness check can be viewed in Figure 4, showing the rate of same state citation as shown in Figure 1, with the remaining plots showing the rate of same state citation measured in the robustness-check.

Figure 4. Robustness graph.

As is apparent from the figure, the rate of same state citation during 2002 as well as 2004 appears to have been inflated by particular judgments with a high rate of same state citation.Footnote 49 But for the remaining years, the same state citation rates calculated closely follow the original.

Considering that the rate of same state citation remains robust most years, and that even the lowest calculated rates of same state citation in 2002 and 2004 exceeds the baseline calculated using United States Supreme Court judgments,Footnote 50 we submit that the rate of same state citation at the sections of the ECtHR is higher than it would be if there was no tendency of state-driven over-citation. As the sub-network citation analysis using Esmark and Olsen’s methodologyFootnote 51 is based on the same dataset, we submit that this analysis is valid as well.

2. Comparing the Same State Citation Rate to that of Another Court

In order to compare our data regarding same state citation practices at the ECtHR, we use the citation practice of the SCOTUS as a baseline. Using the dataset of SCOTUS citations from 1754–2002 created by Fowler and Jeon,Footnote 52 we extract citations from all cases where either the petitioner or respondent were a federal state. We then look at the outgoing citations from those cases to see to what extent those cases cite cases concerning the same state.Footnote 53

We use SCOTUS as a baseline based on an assumption that state-driven same state citation will be less pronounced at this Court, but not nonexistent. On the one hand, the majority of cases heard by SCOTUS do not have a state as either a petitioner or respondent.Footnote 54 This means that a majority of available precedent will not concern states, and that an even smaller amount will simultaneously concern one of the states appearing before the Court in a given case and be of relevance to that particular case. This should lead to a lower reliance on precedent concerning states in general, and specific states appearing before the Court. On the other hand, in certain types of cases, such as those involving states’ rights, citations to prior precedent involving states might be more pronounced.

The reasons why a state would appear before SCOTUS also differs from those of the ECtHR. The ECtHR is part of an isolated complaint system centered on the Convention and its protocols, and the respondent will always be a state, never a person. Conversely, SCOTUS forms part of a regular national legal system where it primarily serves as a final appellate court, and only has original and exclusive jurisdiction in civil cases between federal states.Footnote 55 Thus, states can appear both as petitioners and respondents in a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. We believe that these factors will lead to same state citation being less pronounced, but not so much that it is entirely nonexistent.

Figure 5 shows the percentage of same state citation in cases where the respondent or petitioner is a state.Footnote 56

Figure 5. USSC graph.

The graph shows the rate of same state citation hovering around the five percent mark for most of SCOTUS’s lifetime, with a few spikes reaching or coming close to fifteen percent.Footnote 57 Using this rate of same state citation as our baseline, the historical trend of same state citation at the ECtHR is higher than if it had adhered to a similar trend. This is especially pronounced in the period where the rate of same state citation at the ECtHR was seventy-nine to thirty percent, but even when it decreases to its lowest level in 2016, it is noticeably higher than when compared to even the high points of same state citation at SCOTUS.

It should be noted that if the citation network is reduced to only outward citations to other cases concerning states,Footnote 58 the rate of same state citation becomes much higher, such as reaching 54 percent in 2000. This adjustment of the data is not a valid baseline however, as it removes a large amount of available and cited precedent from the network without accounting for how the USSC’s citation practice might have been different in such a situation.

IV. Possible Implications

As mentioned in the beginning of this article, other studies have engaged with citation patterns of the ECtHR seeking to identify variables which are extraneous to the content of the law itself as explanations for the Court’s citation behavior, for example by focusing on how the Court legitimizes itself before national courts responsible for adapting the ECtHR’s interpretation of the Convention in future domestic cases. Following this approach, Lupu and Voeten conclude that their study “strongly supports the argument that ECtHR judges cite precedent at least in part to provide strategic legitimation for their decisions.”Footnote 59 The citation behavior is, by Lupu and Voeten, perceived to be part of a political game between the Court and other national and international actors and institutions. Our findings could lend support to a similar approach, reasoning that the Court finds it easier to persuade respondent states to comply with the judgement if the Court uses cases that national actors will recognize and understand in its holding. Such an approach would however need further elaboration because it would have to account for the significant variation in same state citation behavior across different responding states. In other words, if the aim of citing former cases against the same state was the same in all cases, namely to leverage political legitimacy for the ECtHR’s rulings vis-à-vis national actors, then why is there such a big difference in citation behavior across different responding states? Our response is to seek an explanation for citation elsewhere—in a more internal legal direction. Instead of relying only on a variable in the data that is external to the content of the law, we want to explore to what degree the law itself can account for the citation patterns of the Court, asking to what degree same state citation can be explained by the factual and legal content of the individual cases. We ask this question in line with the initial question asked in the article—whether the large number and different types of treaty states force the Court into a differentiation of its practice to accommodate for different national contexts. In this way, we would not only speak of a state-driven same state citation, but a context-driven one.

D. Context Specific Same State Citation

As a different and qualitative angle on the question of same state citation, we wanted to explore in more depth what substantial content is to be found in the most particular cases— for example, cases cited most uniformly in actions against the same state. In the above section, our quantitative approach to same state citation runs on a scale from “exclusively used in cases against other states” to “exclusively used in cases against the same state.” In this section, we look at the cases closest to the latter position to explore how state-specific these cases are. The purpose of this section is neither to qualify the above quantitative analysis, nor to give statistically based weight to our main argument. Instead, we want to give qualitative examples to explore how the cases that are most deeply embedded in patterns of same state citation look like.

Our method of extraction is merely a practical measure, guiding us to somewhat the right judgments in order to avoid manually reading through the entire corpus of judgments from the Court. We extracted from our datasetall paragraphs from cases against the fifteen states chosen in the above section, which have been cited at least five times by cases against the same state, and where at least fifty percent of the incoming citations come from cases against the same state.Footnote 60 This gave us a subset of 472 paragraphs from 148 different cases. We then read these paragraphs to assess which of them belong to the context specific type. We classified 226 paragraphs, from fifty-five different cases, as context-specific precedents.

In order to see how these cases are used in their national context, we went a step further, and extracted from our network all cases citing one of the paragraphs extracted in the former step. This gave us a new subset of 2.369 citations from 474 different cases. We then assessed, reading manually through the parts of the cases that cite our first subset, whether they are using them in the same very particular context, or if they are generalizing the content of the precedents to cover other more or less similar situations. We classified 2.293 of the citations, or ninety-seven percent of the subset, as citing the original case in order to explain or legitimize the result in a situation where the context is, essentially, the same. As such, at first instance we can conclude that it is possible to identify clusters of case law in the practice of the ECtHR, which are so bound by their context that they are in fact only applied when the Court is adjudicating on the same particular subject matter against the same responding state.

In the next three sub-sections, we display in more detail some examples of what these state specific clusters of case law look like.

I. The Role of the Serbian Constitutional Court

In our first example-case, Vinčić and Others v. Serbia,Footnote 61 a group of workers had filed a civil suit against their employer, JAT Airways, regarding the non-fulfilment of a payment from the company. Despite the fact that all cases where virtually identical and treated by the same court in the second instance, there seemed to be no transparent system behind who lost and who won their case. Before the Court in Strasbourg, the workers claimed that the inconsistent practice of the Belgrade District Court constituted a violation of their right to a fair hearing, a point of view shared by the ECtHR which found a violation of Article 6, § 1 of the Convention.Footnote 62

Before it got that far, however, the Government objected that the cases were inadmissible due to non-exhaustion of national remedies, as the applicants had not sought redress for compensation at the Serbian Constitutional Court. This was made possible through a series of newer judgments from the Constitutional Court. The ECtHR acknowledged that this was to be considered a part of the nationally available remedies, but noted that this was only after the Serbian Constitutional Court settled the possibility for compensation and the judgement was published in the national State Gazette. Because the applicants lodged their complaint before this date, the Court declared their complaint admissible.Footnote 63

In other successive cases, the Serbian government raised a similar objection; that the applicants had failed to exhaust their national remedies by refraining from going to the Constitutional Court. In Šorgić v. Serbia,Footnote 64 the applicants had not complained to the latter about the length of the inheritance proceeding before filing a complaint to the ECtHR. Upon the Government’s objection, the Court recalled that “a constitutional appeal should, in principle, be considered as an effective domestic remedy … in respect of all applications introduced against Serbia as of 7 August 2008 …. It sees no reason to hold otherwise in the present case.”Footnote 65 In another case, Riđić and Others v. Serbia,Footnote 66 the legal basis for admissibility was slightly more complicated due to the nature of the case and subsequent practice from the Serbian Constitutional Court. Partly based on the original principle from Vinčić, the Court again found that there was no need to appeal to the Constitutional Court in order to exhaust national remedies, linking its result closely with specific national cases and their legal meaning in relation to the facts in the case of Riđić and Others.Footnote 67

While the cases may seem rudimentary and legally somewhat trivial, they display the type of precedent that we were looking for. Starting with an assessment of very nationally particular circumstances, the Court builds a cluster of practice around this combination of reoccurring facts, legal principles from the respondent state—for example, constitutional court practice—and the Court’s own case law.

II. Kılıç and the Situation in Southeast Turkey

One of the prime examples is the line of cases on the situation in Southeast Turkey in the 1990’s. Following the burning down of thousands of Kurdish villages by Turkish military and other security forces, a wide range of cases were filed before the Court relating to a multitude of different human rights violations. In one of them, Kılıç v. Turkey,Footnote 68 the Commission failed to establish who was responsible for the killing of the applicant’s brother, a journalist working at a pro-Kurdish newspaper. Instead, the case centered on the Turkish State’s positive obligation to prevent the assassination of Kemal Kılıç, an obligation that arose because the state had solid knowledge about the danger he was in.Footnote 69 Referring to previous similar cases, the Court argued that the Turkish State had failed to maintain a well-working justice system during the armed conflict in the Southeast regions. The Court thus found a violation of Article 2 of the Convention in that the State failed to “take reasonable measures available to them to prevent a real and immediate risk to the life of Kemal Kılıç.”Footnote 70

The importance of the case lies in the formulation in the ruling that is set forth just before the Court concludes that there has been a violation. As a general observation about the state of affairs in the region at the time of the incident, the Court writes “that these defects undermined the effectiveness of the protection afforded by the criminal law in the south-east region during the period relevant to this case. It considers that this permitted or fostered a lack of accountability of members of the security forces for their actions….”Footnote 71 Five subsequent cases against Turkey on incidents during the same conflict cite this exact paragraph. In Taş v. Turkey,Footnote 72 Muhsin Taş was detained by government security forces but then disappeared without documentation of his detention. Referring to Kılıç, Paragraph 75, the Court noted:

that in the general context of the situation in south-east Turkey in 1993, it can by no means be excluded that an unacknowledged detention of such a person would be life-threatening. It is recalled that the Court has held in two recent judgments that defects undermining the effectiveness of criminal law protection in the south-east region during the period relevant also to this case permitted or fostered a lack of accountability of members of the security forces for their actions …Footnote 73

Kılıç, Paragraph 75 then, is a precedent relating to a very specific and particular national context and a specific period that is used repeatedly in similar contexts against the same state, drawing on the Court’s earlier findings about the state of affairs in these regions. For this reason, Kılıç, Paragraph 75 will not easily transfer into a different national context—and we can see that it does not. Kılıç, Paragraph 75 is only cited by other cases against Turkey.

III. Polish Prison Censorship

The case of Matwiejczuk v. Poland evolved from a question of the length of pre-trial detention and hearing of the applicant’s case within reasonable time. The interesting part in relation to this article, however, is the part of the judgment discussing the monitoring of the applicant’s correspondence. Polish legislation on the subject matter changed during the period in question. In a former judgment, the Court had already laid down that “Polish law concerning the control of correspondence in force before September 1, 1998, did not indicate with reasonable clarity the scope and manner of exercise of discretion conferred on public authorities …,”Footnote 74 and referred back to the relevant judgment.Footnote 75 For a potential breach of Article 8 of the Convention following the change in legislation, the Court established in Matwiejczuk that there had been an interference. It referred in this regard to the fact that the envelope of the allegedly censored letter

bears a stamp: “Censored on, signature” (Ocenzurowano dn. podpis), a hand-written date: 5 March and an illegible signature ….[The Court] considers that even if there is no separate stamp on the letter as such, there is, in the particular circumstances of the case, a reasonable likelihood that the envelope was opened by the domestic authorities. In coming to such a conclusion, the Court takes into account that, in the Polish language, the word ocenzurowano means that a competent authority, after having controlled the content of a particular communication, decides to allow its delivery or expedition.Footnote 76

The Court thus gave an interpretation of how a particular phrase in Polish ought to be understood in relation to censorship of prison inmates’ letters. On the one hand, one can imagine how this is not easily transferable to a different lingual context, but on the other hand might very well be relevant in similar Polish cases. This is exactly so, as we will show in the two following examples.

We find an example of the positive use of the case in Pisk-Piskowski v. Poland.Footnote 77 Again, on the question of the existence of an interference with Article 8 of the Convention, the Court concluded that “there is a reasonable likelihood that the envelope was opened by the domestic authorities.”Footnote 78 The reason?

“[I]n the Polish language the word ocezurowano means that a competent authority, after having controlled the content of the particular communication, decides to allow its delivery or expedition. Consequently, as long as the authorities continue the practice of marking the detainees’ letters with the ocezurowano stamp, the Court has no alternative but to presume that those letters have been opened and their contents read …”Footnote 79

In this case, as well as others citing Matwiejczuk v. Poland, the understanding of this exact word in the context of the substantial situation and the legislation in force was used in a similar, national context as the one in the initial case.

The Court distinguishes away Matwiejczuk on the precise question of the meaning of words in Harakchiev and Tolumov v. Bulgaria.Footnote 80 One of the applicants, Mr. Tolumov, provided evidence that envelopes of his mail had been stamped with the word “checked” by the prison administration.Footnote 81 Nonetheless, the Court rejected his claim, emphasizing that the “checked” stamp did not necessarily indicate that the applicant’s letters had been opened. The fact that it was on the envelope, not on the letter itself, gave the Court “no indication that the letters inside the envelopes were inspected by the prison authorities,”Footnote 82 and there had therefore been no violation of Article 8 of the Convention. This was despite the fact that the relevant Polish legislation in both Matwiejczuk, post-1998, and Pisk-Piskowski as well as the Bulgarian legislation in the present case in principle did allow for the opening of inmates’ mail.Footnote 83 We can see how in the Bulgarian case, the Court reaches a different result despite the apparent material similarities between the cases. The decisive factor, reading the judgment text, seems to be in the exact meaning of the word stamped on the outside of the envelope. Matwiejczuk thereby constitutes another example of how a precedent is produced and used solely in a very particular, national context.

IV. How Does State Centered Precedent Express Itself?

An oft-used phrase in these clusters of case law goes along the lines of A.) the Court has already ruled on a similar case, and B.) nothing the government has said can change the application of reasoning from the previous decision from being applied to the present case. This is not in itself different to how precedent usually work. We did this before, and to assure consistency in our practice, we keep doing it until there is a reason not to. What is different in this situation, however, is that it is not a question of which factors can justify a violation as necessary in a democratic society, which principles to decide how long is too long for a fair trial, or another discussion where the treaty text takes the main stage. Instead, the precedent in these cases are established on somewhat narrow factual circumstances relevant to the state in question, and rarely on any other grounds. This way, a change in the application of the precedent can happen only when the national circumstances have changed—and when the state in question has proved this. Our study thus presents a way of isolating precedent that applies narrowly to individual states.

When we say that these cases are bound by their national context, it is to be taken with a grain of salt, being a descriptive observation rather than a normative one. Surely, by interpreting the cases in the right way, cases such as Kılıç could have been generalized to other cases where treaty rights were violated during armed conflicts between a state and non-state actor.Footnote 84 While legally possible to transfer the precedent value of these rulings—by generalization—to other contexts, we observe that the Court does not do so in the identified parts of our dataset. For whatever reason, the Court seems to preserve them as state-specific precedents rather than as a basis for adjudicating in a broader range of cases.

A final observation is that this context and state-specific precedents seem to take the form of an assumption that there is a breach—or, depending on the case, that a claim of inadmissibility is rejected, as in Vinčić. This is different from application of the treaty-applying precedents, because these general principles usually combine with case-specific circumstances to create the connection between the rule and the particular facts of the case and gives rise to legal reasoning that is characterized by more interaction between convention interpretation and the factual circumstances of the specific case. When the Court applies context-specific precedents, we often see that it skips this two-step form and instead places the facts of the present case in the same interpretive context as the original case. In the absence of any counter-arguments from the respondent state, the Court then establishes, as we quoted from Šorgić above, that “[i]t sees no reason to hold otherwise in the present case.”Footnote 85 The particular facts of the case, which happen to be relevant in the general national context, thereby turn the Court’s precedent application into an assumption of the same results as in the initial case, and the Court will apply this principle in similar cases for as long it takes the state to prove that it has changed the state of affairs. This is not an “assumption of guilt” in a traditional sense, but we find the mechanisms in the application of the context-specific precedents to turn in this direction and away from the workings of the more traditional “rule plus facts” scheme one will otherwise see the Court applying. Because each context and state-specific precedent is used in this way solely against the same state, we find that this questions the view of the Court’s practice as a series of judgments applying a common European convention.

E. The Development Towards a More Homogenous Citation Culture

In the previous section we identified the characteristics of judgment paragraphs that were cited only in cases against the same state. These citations revealed that the cases in which these paragraphs were cited revolved around specific reoccurring factual situations related to systemic conditions within those states. In the section above, we illustrated this by providing three examples of the kind of issues raised in these kinds of cases: Irregularities in access to the constitutional court in Serbia; discriminatory handling in upholding order under civil unrest in Turkey; excessive prison censorship in Poland.

In this section, we wish to address another of our findings. In Figure 1 we can see that the number of same state citations decreases from around seventy to eighty percent in the period of 2000–2005 to around twenty percent in 2017. The contrast is stark, and suggests that more must be going on in the internal working practices of the Court. We provide two different takes on this development. First, we investigate whether the change in same state citation rates is due to a tendency for the Court to slowly generalize its use of the context-specific precedents, meaning that after some time using them solely against the first respondent state, they will start applying them in a broader range of cases. As such, this perspective seeks to explain the development in terms of a change in the use of precedent without going into the social structure producing the citations. Second, we discuss whether changes in the organizational scheme of the Court can contribute to explaining the changing use of precedent.

I. Generalizing Precedents?

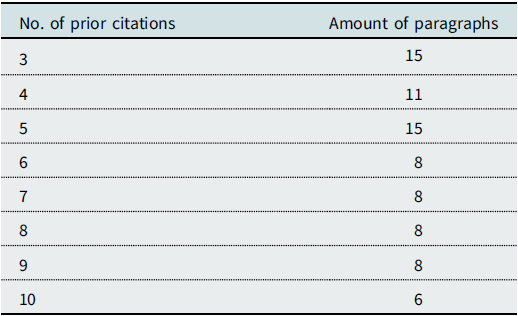

Could an explanation for the downward trend in same state citation be that context-specific precedents become generalized over time, that is, that the context-specific precedents start losing their national character and start being cited outside their initial context? We test this assumption by finding paragraphs that are cited multiple times in cases concerning the same respondent state, and then cited in a case concerning a different respondent state. This is based on the assumption that when a paragraph is cited multiple times in cases concerning the same respondent state, they are more likely to be context-specific precedents, and that once such a precedent is cited in a case concerning a different respondent state, a change from context-specific precedent to a more general precedent is likely. The analysis only covered paragraphs that were cited ten or more times in order to focus on precedents that have found wide support in the case law. Table 3 shows how many paragraphs—right column—are cited a certain number of times—left column—before being cited in a case concerning a different respondent state.

Table 3 Paragraph citations

We have conducted a qualitative review of all the paragraphs that are cited three and four times in cases concerning the same respondent state before being cited in a case concerning another state. The choice of this particular group is based on practical concerns rather than on a value judgment regarding which group might be most interesting to investigate.

Some paragraphs clearly exhibit a citation pattern that indicated a generalization of a national context. Jėčius v. Lithuania, Paragraphs 60–64 concern the incompatibility with Article 5(1) of the Convention of a national rule, which allowed detention on remand when the defendant had been given access to his case file, or the case, had been transmitted to the Court.Footnote 86 The paragraphs are initially cited to reiterate this finding in other cases concerning Lithuania concerning similar circumstances,Footnote 87 but in Khudoyorov v. Russia, they were cited to support a general rule that a bill of indictment is not a sufficient basis to keep defendants in custody.Footnote 88 Babushkin v. Russia, Paragraph 44 contains the applicant’s description of poor conditions in a Russian prison,Footnote 89 and are subsequently cited by the Court to underline that it had previously found violations of Article 3 of the Convention in cases concerning Russian prisons.Footnote 90 Once it was cited in Orchowski v. Poland it had become a general statement regarding what prison conditions are generally deemed so poor that they violate Article 3.Footnote 91 A similar citation pattern exists for Kantyrev v. Russia, Paragraphs 50–51.Footnote 92

In other cases, the national context did not become generalized, but instead was applied analogously to situations in other respondent states. For instance, Jėčius, Paragraph 57 and its subsequent citationsFootnote 93 discuss how access to a case file or the filing of an indictment is an insufficient basis for detention on remand.Footnote 94 Later, in Nevmerzhitsky v. Ukraine, the situation in Jėčius is applied analogously to a similar system in Ukrainian criminal law.Footnote 95 Likewise, Estamirov and Others v. Russia, Paragraph 77 and its subsequent citations concern the fact that Russian civil litigation for damages is not a remedy to be exhausted when complaining that the State has failed to conduct sufficient investigations of conduct contrary to Article 2.Footnote 96 In Isaak v. Turkey, this rationale was applied to the civil courts in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.Footnote 97 Merit v. Ukraine, Paragraph 63 was initially cited to underline that Ukrainian prosecutors did not qualify as independent officers authorized by law to exercise judicial power under Article 5(3), and also that they did not qualify as a remedy to be exhausted as they were not independent judicial authorities.Footnote 98 The precedent was later used comparatively in Zlínsat, spol. s r.o. v. Bulgaria to underline that Bulgarian prosecutors did not qualify as an impartial body under Article 6(1).Footnote 99

Lastly, a paragraph could change character completely, going from a context-specific precedent to a treaty-applying precedent. Włoch v. Poland, Paragraph 125 was initially cited to underline that the Court had previously found violations regarding Polish prisons, but it later ended up being cited to support a general statement of law regarding Article 5(4) of the Convention.Footnote 100

Ultimately however, most paragraphs were either not context-specific precedents to begin with (10),Footnote 101 or if they were, did not have a citation pattern that could be described as a generalization of a national context (5).Footnote 102 In conclusion, the proportion of context-specific precedents that become generalized in the investigated subset of the data, does not allow for a conclusion that this is the reason that the Court’s state driven over-citation has decreased. In the following subsection, we will, as mentioned, provide a more organizationally oriented model of explanation.

II. Changes in the Organization of the Court

This subsection draws on seven semi-structured interviews conducted in Strasbourg from May 6th–10th, 2019, complemented with observations from legal scholars familiar with the internal workings of the Court. The interviews suggest that bureaucratization may provide an explanation for variable citation outcomes, and highlight the integral role played by the Registry in the production of legal pluralism in the case law of the Court.

The Registry is divided into five sections that correspond to the judicial sections of the Court. The sections are further sub-divided into thirty-three case processing divisions.Footnote 103 Case processing lawyers are assigned to these divisions based on legal background, knowledge of languages, and the nationality of the relevant section judges. Registry lawyers are also sometimes split between different sections for high case count member states.Footnote 104 The inherent diversity of a bench of forty-seven ECtHR judges is therefore further heterogenized by a Registry that employs 650 staff members, of whom approximately two-thirds are lawyers that are involved in case processing.Footnote 105

The Registry’s overall function is to prepare for adjudication of applications lodged to the Court. However, the evidence suggests that registry case lawyers perform the bulk of the day-to-day processing.Footnote 106 In effect, registry lawyers prepare and draft the vast majority of ECtHR judgments. Nonetheless, the extent of responsibilities will be affected by the importance of the case for ECHR law. All applications to the ECtHR are initially assigned to a judge or non-judicial rapporteur; and thereafter to a single judge, a Committee of three judges, a Chamber of seven, or the Grand Chamber. Judges generally have only a small input on drafting of cases that are “clearly inadmissible” or “well established case law.”Footnote 107 For Committee and Chamber judgments, the draft prepared by the registry often forms the basis of subsequent deliberations amongst the judges.Footnote 108 The drafts prepared by registry lawyers include a description of facts, the procedural history, the legal reasoning to be adopted, and citations to relevant legal sources—including precedent of the Court. Registry lawyers follow the instructions of the judge rapporteur and implement any request for changes, such as “amendments or, if need be … alternative reasoning.”Footnote 109 However, registry lawyers usually enjoy considerable discretion in the day-to-day processes of drafting. As a prominent observer of the ECtHR has noted—“[the registry] is unseen, but it is heard.”Footnote 110

The Registry is a hierarchical organization, with lawyers categorized based on their experience within the Court. Career lawyers are fully responsible for their work, whilst junior and assistant lawyers work only under the supervision of career lawyers and prepare drafts in “standard form” cases. An internal Registry procedure of “quality checks” of all drafts is undertaken by Section Registrars and their deputies in order to help ensure quality, stringent reasoning, and consistency of case law.Footnote 111 The Jurisconsult further complements this procedure as a quality check between the separate sections of the Registry as the attaché of the Grand Chamber. The Registry therefore functions as the frontline for caseload management by the Court. Registry lawyers furthermore often initiate many of the changes in the working practices of the Court.Footnote 112 The administrative practices of the Court have become rationalized in response to the Court’s increasing workload. In effect, the hierarchy of the internal machinery is increasingly visible in the case law of the Court, as it has come to respond to its demanding docket by rationalizing its processes. There is an increasing drive towards efficiency in the production of its judgments, as one registry employee noted, “the reform of case processing and working methods is constant.”Footnote 113

The data presented in this article should not be considered in isolation from the ongoing reform of the ECtHR. The reform protocols have principally been motivated by the problem of a backlog in applications experienced by the Court, particularly since the enlargement of the ECHR space to Central and Eastern European nations.Footnote 114 In particular, Figure 1 shows a time of transition in 2004–2008 where same state citation declined by as much as forty percent. This transition therefore coincides with a number of developments in the working procedures of the Court.

First, in 2004 the Committee of Ministers adopted “Resolution Res(2004)3” which invited the Court to “as far as possible, identify, in its judgments a violation of the Convention, what it considers to be an underlying systemic problem, and the source of this problem, in particular when it is likely to give rise to numerous applications, so as to assist states in finding the appropriate solution.”Footnote 115 This Resolution, therefore, gave formal expression to the Pilot Judgment Procedure which had been developing in the Court’s jurisprudence. In Broniowski v. Poland, the first pilot judgment, the Court referred to 167 cases pending amongst 70,000 similar applications and imposed general measures that instructed Poland to take “appropriate legal and administrative measures, [to] secure the effective and expeditious realization of the entitlement in question….”Footnote 116 The effect was to relegate the matter back to Poland to settle with the remaining claimants, and the Court struck out a number of applications that arose from this specific factual situation from its list.Footnote 117 Since 2004, the Court has adopted subsequent pilot judgments in order to deal with structural problems arising in Poland, Romania, Turkey, Albania, Italy, Serbia, Slovenia, Russia, Moldova, Ukraine, Germany, Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary, Belgium, and the United Kingdom—amongst other Contracting States.Footnote 118 The precipitous decline in same cite citations in our data on the states chosen for analysis thus coincides with some of the states that have been subject to a pilot judgment. As a result of the pilot judgment procedure the Court is required to deal with less repetitive cases and there is a corresponding decline in context specific precedents of the Court.

Second, and on a more general level, decline of same state citation coincides with the adoption of Protocol 14 by the Committee of Ministers in 2004, a package of amendments to the treaty framework aimed at enhancing efficiency at the Court. The interviews conducted at the Court indicated that in recent years the Registry has undertaken a raft of measures to ensure that its lawyers “start with the same principles and case law citations [and to] take the principle case approach so as to have a more harmonized approach to case law citation.”Footnote 119 Case lawyers increasingly rely on “templates and lists of precedents” in drafting legal reasoning for well-established case law, and are encouraged to refer to specific ECtHR cases as a general principle or a summary of relevant law.Footnote 120 The quality check undertaken by senior registers now also refers to templates of relevant ECtHR case law, thereby reinforcing a more unified approach to legal reasoning that is emerging in the judgments.Footnote 121 The establishment of Single Judge Formations, Three Judge Committees, and the Filtering Section within the Registry in 2010 is also likely to have shifted further responsibilities to the registry in the drafting of judgments.Footnote 122 On a path to efficiency, the drafting of legal decisions has become more streamlined within the Court. The data does not reveal a large decline in same state citation since the coming into force of Protocol 14 in 2010. However, evidence suggests that the effect of reform protocols may be visible in the Court’s jurisprudence following adoption—the ECtHR is receptive to political signals and takes action where it can appropriately.Footnote 123 As many working documents are internal, it is difficult to point to times when measures are adopted. However, reform of registry practice was likely to affect gradual decline in same state citation in its wider body of case law.

In sum, the ECtHR is a relatively plural social field, yet its internal machinery has tended toward rationalization. In this data, it is likely that the introduction of the pilot judgment procedure to deal with repetitive cases facilitated a dramatic reduction in pending cases and therefore, repetitive citations to cases against the same state and with the same facts. This has occurred in the context of the introduction of a group of reform measures that were intended to create a more unified and therefore, predictable body of jurisprudence to deal with the Court’s burdensome workload.Footnote 124 On the other hand, the interviews further revealed a paramount concern for justice in the individual case that is often times not immediately visible from the representational structures of the Court’s case law. As one registry lawyer noted, the facts of a case do not always fit the templates of the Court’s “well established case law.”Footnote 125

F. Conclusions and Further Perspectives

In this article, we sought to address whether European law is in fact European, or whether instead there is reason to perceive the practice of the ECtHR in a more pluralist way, in the sense that it is possible to identify particular strands of case law in the form of what we dubbed context-specific precedents. In order to address this general question, we engaged in a study of the Court’s citation practice on two levels.

First, we find support of our claim that the Court’s practice is to a large extent split between different states, and that it generally prefers to cite cases against the same state that it is adjudicating. While this tendency is on a decline in the overall network of citations, there are large fluctuations when the data is split up according to the respondent states. Not only is there a difference in the cases the Court uses depending on the respondent state, there is also a difference as to what degree this pattern is visible. This conclusion addresses earlier research in the Court’s citation patterns, contrary to which, we suggest that the respondent state is important when the Court chooses which cases to cite.