I. INTRODUCTION

Climate change litigation against corporations is growing in different fora,Footnote 1 including climate-related complaints filed under the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (the Guidelines).Footnote 2 The Guidelines are principles and standards on responsible business conduct addressed to multinational enterprises (MNEs) operating in or from States that adhere to the 1976 Declaration on International Investment and MNEs (the Declaration), but they do not legally bind MNEs. Their scope is broad and covers human rights; employment and industrial relations; environment; bribery and other forms of corruption; consumer protection; science, technology and innovation; competition; and taxation. Although the Guidelines are non-binding in relation to companies, States adhering to the Declaration are obligated by a legally binding Decision of the OECD CouncilFootnote 3 to promote and support their implementation, including by establishing National Contact Points (NCPs), a unique form of State-based non-judicial grievance mechanism and a platform for promoting corporate observance of the Guidelines. The Guidelines can thus be understood as a soft-law instrument targeting areas that States have a hard-law obligation to promote.

All parts of the Declaration, including the Guidelines, are subject to periodic reviews.Footnote 4 In 2011, the OECD arranged a full review of the Guidelines and added a dedicated human rights chapter consistent with the United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) (2011 Update).Footnote 5 In the 2011 Update, the OECD introduced the concept of risk-based due diligence, derived from the UNGPs, in Chapter II (‘General Policies’) and applied the concept to human rights and additional areas of responsible business conduct.Footnote 6 This revision thus introduced a concept that has, over the course of the subsequent decade, become critical in debates over corporate accountability on the issue of climate change.Footnote 7 The 2011 Update did not explicitly mention climate change, but it did encourage reporting on greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions.Footnote 8 It also referred to related concepts that are commonly understood to include climate action, such as ‘sustainable development’. Since 2011, the discursive landscape on responsible business conduct standards has drastically changed. Notably, as key stakeholders have increased their scrutiny of the environmental and human rights impacts of business, they have paid closer attention to the interconnection of these issues.Footnote 9

In 2022, the OECD Working Party on Responsible Business Conduct began work on a targeted update of the Guidelines to address evolving perspectives on responsible business conduct. A consultation draft was released in January 2023.Footnote 10 On 8 June 2023, during a Ministerial Council Meeting, the OECD launched an updated version of the Guidelines (2023 Update).Footnote 11 The changes have substantial and potentially far-reaching implications for business, particularly in the areas of climate change and biodiversity. Significantly, the 2023 Update explicitly identifies climate change as a critical environmental impact that MNEs should address by conducting risk-based due diligence, acknowledges that MNEs have a responsibility for achieving a ‘just transition’, and states that the Guidelines are now consistent with the Paris Agreement of 2015.Footnote 12

The inclusion of climate change and corresponding corporate responsibilities in the 2023 Update was both timely and widely anticipated. There is a growing recognition that corporations must contribute to global efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change.Footnote 13 The Paris Agreement emphasizes the critical role of the private sector in addressing climate change by calling for collaborative efforts between governments and businesses ‘to reduce emissions and/or to build resilience and decrease vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change and demonstrate these efforts’.Footnote 14 Consequently, the international climate change regime now features a stronger and more explicit role for non-State actors, including corporations and transnational governance initiatives.Footnote 15

The 2023 Update brings the OECD's responsible business conduct regime more firmly into the fold of the global governance complex for climate change.Footnote 16 While the Guidelines are not a hard-law instrument, they are now in alignment with international instruments (ie the Paris Agreement) that are considered binding on States. The 2023 Update affirms adhering governments’ expectations of companies and at least partially institutionalizes the norm of corporate climate due diligence. Where companies apply the Guidelines or similar standards in their operations or join multi-stakeholder initiatives that promote or monitor compliance with such standards, this may be understood as a diffusion of the public authority found in the hard-law instruments with which the Guidelines are aligned.Footnote 17

This global governance complex includes UN-backed campaigns, such as the Race to Zero, that aim to mobilize non-State actors, including corporations, to commit to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.Footnote 18 Outside the UN system, more than 4,000 businesses collaborate with the Science Based Targets initiative to set and implement emissions reduction targets.Footnote 19 Many industries have also established sectoral initiatives to drive collective action on climate change. For instance, the Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action, launched during the 2018 UN Climate Change Conference, aims to achieve net-zero emissions in the fashion industry by 2050.Footnote 20

Although such transnational governance initiatives rarely expressly refer to the OECD Guidelines or the human rights principles that inform them, the crucial role of non-State actors in climate action has been recognized by the international human rights regime. A Statement from the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2018 stressed that ‘[c]omplying with human rights in the context of climate change is a duty of both State and non-State actors’.Footnote 21 In June 2023, the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights published its first information note on climate change and the UNGPs that explains how the UNGPs can assist States, business enterprises and other actors to integrate the actual and potential impacts of climate change with other human rights-related impacts that business activities cause or to which they contribute or are linked.Footnote 22

The 2023 Update consolidates many of these developments and provides clearer and stronger expectations of MNEs regarding actions to mitigate the impacts of climate change. The enhanced clarity on these corporate responsibilities may facilitate an increase in mitigation action from corporations, or, failing that, it may lead to an increase in the pace and expansion of the scope of climate-related complaints referred to the NCPs. This article examines the 14 climate-related complaints filed with NCPs prior to the 2023 Update. It then analyses corporate climate change responsibilities under the 2023 Update of the Guidelines and discusses how the new text may influence understanding of these responsibilities compared to the concepts advanced in previous complaints. The article makes two key contributions: first, it charts the progress of climate-related complaints filed prior to June 2023 and anticipates how the 2023 Update might influence future complaints, and second, it explores the connection between the human rights and climate change dimensions of the Guidelines, a topic widely studied and applied in research and practice outside the NCP system,Footnote 23 but less explored within it.

II. THE GUIDELINES: A SOFT-LAW MECHANISM FOR CORPORATE ACCOUNTABILITY

The Guidelines remain one of the most prominent international standards for responsible business conduct. The soft-law nature of the Guidelines, enforced by a State-based but non-judicial grievance mechanism, affords a certain level of flexibility compared to litigation in the courts.Footnote 24 The Guidelines employ precise language to make it clear that compliance with its provisions is voluntary for MNEs, and thus they represent a very low degree of obligation for States and businesses,Footnote 25 although governments have a binding obligation to promote the Guidelines and maintain an NCP. The Guidelines were always intended to be a soft-law instrument; indeed, the initial version of the Guidelines was adopted in 1976 ‘rather hurriedly to pre-empt the parallel efforts of the United Nations’, which were made in pursuit of a binding international corporate code of conduct that was fiercely contested by OECD States.Footnote 26 Nonetheless, legal scholars have argued that the Guidelines contain ‘characteristics associated with hard law’ including some precision on standards of corporate conduct and delegation to third parties in the form of NCPs.Footnote 27 Many of the limitations of the Guidelines can be attributed to their weak enforceability.Footnote 28 The Guidelines have always been voluntary for MNEs, and the NCPs act as a ‘forum for discussion’ in the first instance.Footnote 29

OECD members agreed in 1984 to establish NCPs within each adherent government to further the effectiveness of the Guidelines. By the 1990s, NCPs had become largely defunct amidst a loss of interest in them, especially from trade unions.Footnote 30 During the revisions to the Guidelines in 2000, a conference of stakeholders agreed to reinvigorate NCPs by giving them a clearer mandate and proper remedial role, although adhering States retained considerable autonomy in deciding on the structure and scope of the NCPs.Footnote 31 NCP complaints are called ‘specific instances’, and the process for handling them is governed by Procedural Guidelines attached to the Guidelines. The Procedural Guidelines outline the five aspects of NCPs: institutional arrangements; information and promotion; implementation in specific instances; support for government efforts to promote responsible business conduct; and reporting.Footnote 32 NCPs do not have the power to issue binding judgments or to compel companies to provide monetary compensation for right-holders.

There remains considerable disparity in national approaches to setting up NCPs.Footnote 33 In some States, NCPs are located within the government department concerned with foreign investment, which may adversely affect the impartiality of the specific instance process.Footnote 34 Lack of financial and human resources is one of the main criticisms of the NCP system.Footnote 35 While some NCPs are well resourced, many others have limited budgetary allowances.Footnote 36 By 2014, a third of NCPs had yet to receive a complaint, suggesting their relative invisibility or unresponsiveness.Footnote 37 The absence of policy coherence and uniform structural rules may negatively affect the efficiency of NCPs. Some NCPs include specific recommendations to companies in a final statement at the end of the specific instance process or determine whether a particular company has followed the Guidelines.Footnote 38 Some NCPs do not publish details of complaints, while others do.Footnote 39 Other issues identified as hampering NCP effectiveness include: lack of visibility and accessibility; difficulties in managing cases efficiently and non-conformity with procedural timelines; and inability to ensure the fairness and safety of the process.Footnote 40 Governments have also been inconsistent with regard to the material consequences of corporate non-cooperation with NCP processes and rulings. Some have developed strategies and incentives to promote compliance, while others have never stated publicly how they will treat non-cooperating businesses.Footnote 41 At the same time, NCPs offer some benefits. They have facilitated normative innovation, and they often move faster than court and quasi-judicial international and regional proceedings, even as NCPs are themselves criticized for slow decision-making.Footnote 42

The effectiveness of the Guidelines and the NCPs continues to be debated. Despite challenges and limitations, NCPs remain an important forum for affected parties to initiate a dispute against MNEs and engage in dialogue. The broad scope of the Guidelines means that NCPs are capable of hearing complaints on a diverse range of issues. Data on specific instances from 2000 to 2014Footnote 43 showed that NCPs were primarily used as a human rights mechanism. The trend of using NCPs to address human rights issues was reaffirmed with the inclusion of human rights provisions in the Guidelines in 2011. Over the same time period, NCPs saw an increasing diversity of human rights cases, began to focus more on specific due diligence provisions in complaints, and had a higher admissibility rate for human rights cases than for other types of cases. As of 2020, ‘the most prevalent themes that dominate NCP cases [were] human rights, due diligence and labour relations’, indicating that the trend continues.Footnote 44 However, the OECD has acknowledged that over time ‘[c]ases handled by NCPs have increased in terms of the complexity of issues and the number of geographies involved’.Footnote 45

This emphasis on human rights and due diligence in the corpus of complaints filed before the NCPs may in part be attributable to efforts to promote norm convergence in this area over the course of the past two decades. The Guidelines explicitly incorporate the steps of human rights due diligence and explanatory language from Pillar II of the UNGPs—focused on the corporate responsibility to respect human rights—which are also a non-binding soft-law instrument. The inclusion of these provisions is a result of John Ruggie, the former UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General who developed the UNGPs, adopting an ‘active engagement effort’ to achieve convergence around the UNGPs amongst international standard-setting bodies, including the OECD.Footnote 46 Thus, the 2011 human rights chapter in the Guidelines was drawn almost verbatim from the UNGPs and the concept of due diligence now occupies a prominent position within OECD policy rhetoric.Footnote 47 Ruggie's efforts also explain why the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines closely reflect due diligence standards in, eg, the International Finance Corporation Sustainability Principles and Performance Standards, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 26000 standard, and policy programmes from the European Union (EU), African Union and Association of Southeast Asian Nations.Footnote 48 Scholars have noted the high degree of convergence around the UNGPs, including in the Guidelines and also in other global governance institutions and policy instruments.Footnote 49

Despite the increasing focus on human rights, risk-based due diligence practices are not prominent in the body of complaints filed to the NCPs. Furthermore, despite the emerging understanding of climate-related human rights due diligence discussed in the Introduction, there is a noticeable lack of explicit connections between climate and human rights in many of the climate-related NCP complaints filed prior to the adoption of the 2023 Update. In the next section, the growing trend of filing climate-related complaints under the Guidelines is examined. The key climate issues that have been raised in these complaints are outlined and the current limited integration between human rights and climate due diligence is analysed.

III. THE 2011 UPDATE AND CLIMATE-RELATED NCP COMPLAINTS

A total of 14 NCP complaints concerning climate change were filed before June 2023, when earlier versions of the Guidelines applied. The 2011 Update included general provisions about MNEs’ expected environmental conduct, but it did not explicitly address climate change and its impacts. There was a reference to GHG emissions in the commentary to Chapter III (‘Disclosure’) encouraging MNEs’ disclosure in ‘areas where reporting standards are still evolving, such as, for example, social, environmental and risk reporting’.Footnote 50 Additionally, Chapter VI recommended that MNEs improve environmental performance by developing and producing products and services that reduce GHG emissions and providing accurate information on their products (for example, on GHG emissions, biodiversity, resource efficiency, or other environmental issues).Footnote 51 Otherwise, the 2011 Update did not explicitly include climate issues, which NCPs have noted in select specific instances. In Australian Bushfire Victims and Friends of the Earth Australia v ANZ Bank, for example, the Australian NCP highlighted the Guidelines’ ambiguity regarding climate change.Footnote 52 During the last stocktake of the Guidelines, the OECD also admitted they lacked clear expectations on climate mitigation, adaptation, or just transition principles.Footnote 53

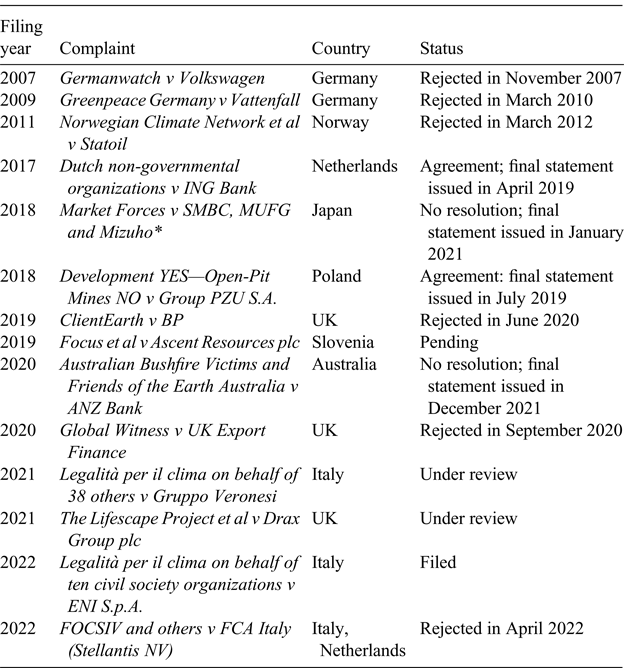

The 14 climate-related complaints filed under previous versions of the Guidelines were filed before NCPs in nine different States, with the majority filed since 2018 (see Table 1). This increase in activity in recent years mirrors a broader global trend in climate litigation, which has seen a rapid increase in the number and diversity of cases since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015.Footnote 54

Table 1: Complaints filed by year and country

* Three complaints were filed against the three banks, but these are treated as one complaint given that they are essentially identical. Each concerns the banks’ financial support for the same four coal-fired power plants in Vietnam and all three complaints are based on the same set of arguments.

Source: OECD Complaints Database <https://www.oecdwatch.org/complaints-database/>; and the Climate Change Litigation Databases maintained by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law <https://climatecasechart.com/>. The status of each complaint is current as of 11 April 2024.

The authors group these specific instances according to three key issues central to the arguments in each case, identified in the authors’ review of the complaints: (A) responsibility to reduce (direct and indirect) GHG emissions; (B) greenwashing and misinformation; and (C) just transition. In so doing, the authors draw on an earlier review of complaints conducted in 2021.Footnote 55 Notably, one key climate issue that has formed the basis of climate change litigation elsewhere—concerns regarding MNEs’ practices on adaptation—is absent in the 14 complaints under examination here.Footnote 56 This is a significant gap given that an MNE's ‘failure to adapt’ facilities and operations to withstand physical climate impacts can lead to significantly increased damage to local communities. As noted below, this may now change with the 2023 Update to the Guidelines, which explicitly covers MNEs’ responsibilities in this area.

A. Responsibility to Reduce Direct and Indirect GHG Emissions

In the following discussion, it is observed that (1) early complaints filed before the finalization of the Paris Agreement in 2015 and the 2011 Update of the Guidelines were largely rejected by the respective NCPs. However, since the filing of these complaints, there has been a notable shift in public perception concerning corporate responsibility to reduce GHG emissions resulting from business operations. Presently, both State and numerous non-State actors recognize the critical role the private sector must play in achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement.Footnote 57

This evolving perspective sets the stage for an upswing in NCP complaints concerning emissions reduction responsibilities, with a significant focus on the promotion and support for ongoing fossil fuel exploration and production (seven out of 11 complaints filed since 2018 pertain to fossil fuels). Other noteworthy trends in the existing complaints include: (2) an increased emphasis on the role of finance, with five out of the seven complaints filed since 2018 targeting financial institutions; and (3) relatively limited engagement with the human rights dimension of climate change in complaints brought against both fossil fuel companies and financial institutions.

1. Complaints filed before the Paris Agreement

The two earliest climate-related NCP complaints (both in Germany) dealt with substantive emissions reduction obligations. The first was filed by the non-governmental organization Germanwatch against Volkswagen in 2007. It alleged a violation of the Guidelines as a result of the company's failure to conform with climate protection goals, including through conducting lifecycle assessments of its products.Footnote 58 The other complaint was filed by Greenpeace Germany against Vattenfall, on the basis that ‘Vattenfall's insistence on generating electricity from coal-fired power plants stands in contradiction to today's climate protection goals’.Footnote 59 Another early complaint was filed with the Norwegian NCP in 2011 by the Norwegian Climate Network and Concerned Scientists Norway against Statoil ASA regarding the incompatibility of oil sands operations with the sustainability provisions of the Guidelines. All three complaints were rejected by the respective NCPs on the grounds that the issues raised were outside the scope of the Guidelines. In dismissing the Vattenfall complaint, for example, the NCP noted that it was founded on an overly broad interpretation of the Guidelines, given that Vattenfall's actions consisted of ‘the legally acceptable generation of electricity from coal’.Footnote 60

2. Obligations of financial institutions and aligning financial flows with the Paris Agreement

Five of the complaints concerning emissions reductions and alignment with the goals of the Paris Agreement have been filed against financial institutions, including three banks, an insurance company and the UK's export credit agency. This signifies the growing awareness of the impact of financial decisions on climate change and emissions reduction efforts.

Civil society organizations filing these complaints have emphasized ‘financed emissions’, reflecting a growing global concern with the need to align financial flows to ensure a transition to a low-carbon, resilient world, in line with Article 2(1)(c) of the Paris Agreement.Footnote 61 These arguments also align with a growing trend in climate litigation, with several recent cases brought against financial institutions.Footnote 62 The issues raised in these complaints are complex, including questions about appropriate methodologies to assess the extent of financed emissions and the best approaches to address emissions once identified.

Examining this set of cases, it is notable that NCPs have provided limited clarity on the extent of emissions reduction responsibilities under the Guidelines. Two cases illustrate competing views. In its final statement in the ING Bank case, the Dutch NCP noted that:

the OECD Guidelines demand that ING, and other commercial banks, put effort into defining, where appropriate, concrete targets to manage its impact towards alignment with relevant national policies and international environmental commitments. Regarding climate change, the Paris Agreement is currently the most relevant international agreement …Footnote 63

Despite recognizing the challenges in implementing systems to address this issue and the limited influence banks may have on their customers, the NCP's final statement unequivocally encouraged action.

The Australian NCP in the ANZ Bank case, on the other hand, took a different approach despite several similarities in the nature of the complaint. Noting the complexity in this evolving area, the NCP argued that ANZ had evidenced a high degree of ‘engagement’ with climate issues and had therefore discharged its obligations under the Guidelines sufficiently. Following a lengthy exposition of the Guidelines and their history, the NCP noted: ‘it is important to distinguish between “ANZ's consistency with the Guidelines” and “the Guidelines’ consistency with contemporary expectations regarding climate change”’.Footnote 64 The NCP argued that, on the latter point, the Guidelines stopped short of providing clear expectations or setting standards and recommended that this be remedied in future revisions. These cases illustrate the challenges NCPs faced in interpreting the pre-2023 text of the Guidelines in a way that conforms to contemporary expectations of responsible business conduct in the climate context.

3. Human rights due diligence in the climate context

An interesting aspect of the existing NCP climate complaints is their relatively limited engagement with the human rights dimension of climate change. The fundamental interlinkage between climate change and human rights has now been firmly established, with over 200 climate cases before domestic and international courts and tribunals based on human rights grounds.Footnote 65 Most notably, a corporate due diligence obligation to reduce emissions was recognized in a 2021 decision by the Hague District Court in the case of Milieudefensie v Shell, which interpreted the unwritten standard of care under Dutch tort law to conform with contemporary expectations regarding the human rights responsibilities of enterprises, relying in part on both the Guidelines and UNGPs.Footnote 66 There is growing international political pressure for businesses to apply the concept of ‘human rights due diligence’ to climate change. This was further confirmed by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, David Boyd, in a 2019 report.Footnote 67 In 2021, the UN Human Rights Council also established a Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change, whose mandate includes working with businesses to adopt a human rights perspective on climate issues in accordance with the UNGPs.Footnote 68 In June 2022, the first mandate holder, Ian Fry, published his first report, identifying six thematic priorities for the first three years of his mandate, one of the priorities being the review of climate law-making and litigation at the national and regional level, particularly litigation against corporate actors which relies on human rights and environmental due diligence legislation.Footnote 69

Despite these developments, the complaints examined in this article make sparse reference to this emerging area of global policy and jurisprudence. The two Italian complaints against Rete Legalita raise human rights issues, but from the information currently available it appears they do so without detailed argumentation on the linkages between the climate damage complained of and human rights impacts. The first complaint challenged the compatibility of intensive livestock farming with the need for action to address the climate emergency.Footnote 70 The complainants alleged that intensive livestock farming is a significant anthropogenic source of methane emissions, as well as carbon dioxide and various other air pollutants. They argued that by refusing to conduct the appropriate risk assessment, companies involved in intensive livestock farming violated a series of responsibilities under the Guidelines, including respect for human rights.

The second complaint concerns the worldwide climatic impacts of the industrial plan of ENI related to the extraction and marketing of fossil fuels. The complainants allege that ENI's refusal to produce a serious analysis of the climate risks connected with its own activity violates various substantive provisions of the Guidelines, including respect for human rights and the environment.Footnote 71 A more detailed discussion of these issues is provided in the complaint filed against Ascent Resources in Slovenia, but, again, the arguments were not elaborated in significant detail. This complaint alleges that the company's hydraulic fracturing activities in Slovenia are highly detrimental from an environmental and public health perspective, mainly due to the use of dangerous chemicals, and place human rights at greater risk.Footnote 72

Nearly identical complaints filed against the Japanese banks Mizuho, SMBC and MUFG all concern financing provided to a series of high emissions-intensity coal-fired power plants in Vietnam and contain some of the most detailed human rights arguments of any of the climate complaints filed with NCPs to date. However, the complaints largely emphasize the local human rights impacts of the power plants, focusing on local air pollution and its impacts on communities, rather than on the more attenuated connection between the cumulative impacts of coal power on the climate and adverse human rights impacts subsequently resulting from climate change. Similarly, the PZU complaint to the Polish NCP, which concerns the ongoing provision of insurance to coal power plants, alleged that the company failed to conduct adequate due diligence regarding the human rights impacts of such power plants, particularly on the right to health.

B. Greenwashing and Misinformation

Both the ‘Environment’ and the ‘Disclosure’ chapters of the 2011 Update specified that enterprises have a responsibility to provide clear, accurate and measurable information regarding the environmental impacts of their products and services. Several existing climate-related NCP complaints have raised concerns about greenwashing and misinformation under these provisions, as well as under provisions relating to consumer protection.Footnote 73

Until recently, the most substantial of these specific instances was the complaint filed against BP before the UK NCP by ClientEarth in 2019. The complaint questioned the accuracy of statements made by the company in advertising campaigns for its renewable energy operations. ClientEarth alleged that the advertisements obscured the company's broader contributions to adverse climate and environmental impacts. The case was initially accepted on the basis that the issues were material and substantiated, but it was subsequently discontinued by the NCP after BP withdrew the advertisements and undertook not to replace them. More recently, a complaint has been filed in the UK against Drax Group plc regarding the accuracy of its statements on the climate-friendliness of burning woody biomass to produce power. In its initial assessment, the NCP accepted that all but one of the claims made in the complaint were ‘material and substantiated’.Footnote 74

C. Just Transition

The final issue raised in the existing body of climate-related NCP complaints is the question of a ‘just transition’, referring to the potential adverse social and economic consequences of projects meant to transition to a low-carbon economy or adapt to climate change. To date, this issue has arisen in only one case: FOCSIV and others v FCA Italy (Stellantis NV). The complaint concerns the enterprise's lack of disclosure regarding the potential human rights and environmental impacts of the company's cobalt mining operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The complaint was initially filed with the Italian NCP but was rejected on the basis that Stellantis, the parent company, was based in the Netherlands. A subsequent complaint was filed before the Dutch NCP, where it has been accepted. Although the complaint does not pertain to the company's responsibility to reduce emissions or adapt to climate change, it is relevant to the transition to a low-carbon economy since cobalt is one of several critical minerals required for ongoing electrification programmes introduced as part of countries’ decarbonization efforts. As such, it can be understood as one of a growing number of cases that raise concerns about the human rights implications of action taken to respond to the climate imperative, which scholars call ‘just transition litigation’.Footnote 75

IV. THE 2023 UPDATE AND LOOKING AHEAD

In contrast to previous versions of the Guidelines, the latest text explicitly incorporates climate change considerations.Footnote 76 Climate change is evident across multiple sections, with particular emphasis on the interconnections of climate change and other areas of responsible business conduct. The Foreword to the 2023 Update lists several key updates, placing ‘recommendations for enterprises to align with internationally agreed goals on climate change and biodiversity’ at the forefront. In this section these new provisions are examined, and insights are provided into their potential implementation, exploring the implications for NCPs in light of past OECD jurisprudence.

A. Preface

The 2011 Update mentioned the need for a business contribution to sustainable development outcomes.Footnote 77 The Preface to the 2023 Update specifies that these outcomes include global ‘solutions to address and respond to climate change’.Footnote 78 The Preface of the 2023 Update places a stronger and more explicit emphasis on risk-based due diligence procedures, and like the 2011 Update, it emphasizes coherence between economic, environmental and social objectives.Footnote 79 Paragraph 4 of the Preface notes the importance of risk-based due diligence as a means to address ‘matters covered by the Guidelines’, suggesting that such due diligence should be applied to all matters covered by the Guidelines. As environmental objectives are now explicitly defined to include climate change, this aspect of the 2023 Update may facilitate greater integration of climate and human rights, strengthening the case for NCP complaints that invoke climate-related human rights due diligence responsibilities. However, as discussed below, climate change is not mentioned in Chapter IV (‘Human Rights’) and the terms environmental due diligence and human rights due diligence are differentiated in places.

B. Chapter III (‘Disclosure’)

Climate change is also mentioned in the commentary on Chapter III (‘Disclosure’) in the 2023 Update. Paragraph 33 states that ‘[u]sers of financial information and market participants need information on … material risks that may include: … responsible business conduct risks; … notably climate-related risks’.Footnote 80 Paragraph 37 adds an explicit reference on climate change to the previous text on voluntary codes of corporate conduct to note that they may include commitments on climate change.Footnote 81 Paragraph 38 then states that enterprises ‘should seek to adopt and align with emerging global best practice and evolving disclosure standards, for example on climate and emissions’ in addition to and where consistent with legal requirements in the jurisdiction where the enterprise operates.Footnote 82

These provisions are clearly related to what this article categorizes as ‘greenwashing and misinformation’ complaints under the NCP system. While previous complaints have been fairly successful in either inducing change in corporate practices (as in the complaint filed against BP discussed above) or securing favourable decisions from NCPs, the 2023 Update provides greater clarity on the importance of information accuracy and transparency and should enhance complainants’ ability to contest suspected greenwashing activities by providing NCPs with an authoritative mandate to investigate such conduct with explicit reference to climate-related disclosures.

C. Chapter VI (‘Environment’)

Chapter VI opens with a compelling acknowledgement of the key role that enterprises play in developing an ‘effective and progressive response to global, regional and local environmental challenges, including the urgent threat of climate change’.Footnote 83 The 2023 Update provides a non-exhaustive list of environmental impacts that may be associated with business activities including: (a) climate change; (b) biodiversity loss; (c) degradation of land, marine and freshwater ecosystems; (d) deforestation; (e) air, water and soil pollution; and (f) management waste, including hazardous substances.Footnote 84 Chapter VI incorporates a statement that enterprises should carry out risk-based due diligence to identify, assess and address adverse environmental impacts.Footnote 85

Climate issues are prominent in the commentary on Chapter VI. Paragraph 66 outlines the Guidelines’ expectations concerning how enterprises can contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation.Footnote 86 These expectations encompass the promotion of ‘circular economy’ approaches and emphasize the significance of using international commitments and multilateral agreements as an ‘important benchmark’ for understanding environmental issues and expectations. It also refers to scientific evidence as an ‘important reference’. Notably, the text of the Guidelines is meant to reflect the principles and objectives of the Rio Declaration on Environment and DevelopmentFootnote 87 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.Footnote 88 Paragraph 66 also acknowledges consistency of the Guidelines with a range of important international conventions, including the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement.Footnote 89

It is likely that future NCP complaints will increasingly draw upon these diverse frameworks and policies to interpret corporate responsibilities related to climate change. One prominent aspect that complaints might rely on is the global goal of limiting the temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, as enshrined in Article 2 of the Paris Agreement. The argumentation in such complaints might therefore reflect the approach seen in judicial cases filed before domestic courts, such as that used in Milieudefensie v Shell discussed above.

Paragraph 67 acknowledges the broad scope of environmental management,Footnote 90 which involves carrying out risk-based due diligence in line with Chapter II (‘General Policies’). The text of paragraph 67 refers to ‘environmental due diligence’, suggesting that it is different from ‘human rights due diligence’ to be carried out by the enterprise under Chapter IV (‘Human Rights’). The lack of a clear and definite link between human rights and environmental due diligence in the 2023 Update is a missed opportunity and fails to address the growing consensus that climate change threatens the effective enjoyment of a range of human rights.Footnote 91 While complaints filed under the 2023 Update may nonetheless try to make the case for a more integrated understanding of the two subjects, the lack of explicit guidance may result in the practice of the NCPs falling behind expectations of responsible conduct that may emerge from other areas of legal practice or the kind of evolving societal expectations referred to in the Final Statement in the ANZ Bank case noted above.

Paragraph 68 highlights the importance of available science in assessing adverse environmental impacts.Footnote 92 It also refers to three different concepts—cause, contribute and directly linked—to define an enterprise's connection to such impacts.Footnote 93 However, determining the extent of an enterprise's responsibility for ‘causing’, ‘contributing to’, or ‘having a direct link to’ human rights or environmental abuses is a complex topic in responsible business conduct.Footnote 94 Previous specific instances and NCP case history have not thoroughly addressed this topic, leading to uncertainty in interpreting these concepts, despite the differentiations provided by the Guidelines and the UNGPs.

Paragraph 68 attempts to clarify these concepts by explaining that an enterprise: (i) ‘causes’ an adverse impact when its activities alone are sufficient to result in the impact; (ii) ‘contributes to’ an adverse impact when acting together with another entity or otherwise facilitating and incentivizing such entity to cause an adverse impact; and (iii) is ‘directly linked to’ an adverse impact via its business operations, products or services by a business relationship.Footnote 95

However, when it comes to anthropogenic global warming, defining how enterprises can cause, contribute to, or be linked to such impacts adds another layer of complexity. Further guidance may be necessary to clarify how these definitions should be applied to frame corporate climate change responsibilities in practice and to inform future NCP decisions. Even if direct or indirect emissions of an individual enterprise have a causal link to global temperature increases, this is a problem that derives from the cumulative historic emissions of a plurality of subjects, as well as from the insufficient preventative and mitigating action undertaken by governments.Footnote 96 The cumulative aspect of the problem structure renders it particularly challenging to attribute specific human rights abuses resulting from climate change to individual enterprises. While this may not pose major challenges for complainants seeking to argue that MNEs must align their activities with global climate goals as a means of preventing or mitigating adverse impacts, providing a remedy to climate impacts is likely to remain a challenging issue, particularly in light of paragraphs 76–79 of the commentary, as discussed below.

Paragraph 70 is an entirely new addition to the Guidelines and emphasizes the interconnections of climate with other issue areas,Footnote 97 again potentially strengthening climate-related NCP complaints that rely on human rights arguments. This paragraph also invokes the Paris Agreement's reference to a ‘just transition’ of the workforce and creation of decent work and quality jobs and of the need to consider respective obligations in climate actions. While the Paris Agreement binds only States, the 2023 Update here states that ‘it is important for enterprises … to take action to prevent and mitigate adverse [social] impacts both in their transition away from environmental harmful practices, as well as towards greener industries or practices, such as the use of renewable energy’.Footnote 98 This provision could increase the likelihood of more just transition complaints as it clarifies that business does not abdicate its human rights responsibilities and the need for a social license to operate when it engages in climate-aligned projects.

Paragraphs 76–79 align the Guidelines with the Paris Agreement, such as by explicitly expecting enterprises to transition to net-zero GHG emissions and take into account scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.Footnote 99 Paragraph 76 is closely aligned with the text of Integrity Matters, the recommendations published by the UN High-Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Emissions Commitments of non-State Entities (HLEG) in November 2022.Footnote 100 They also align with the ISO Net Zero Guidelines, adopted in 2022 in an effort at harmonization with the HLEG.Footnote 101 Like these instruments, Paragraph 76 of the 2023 Update details the need to prioritize GHG emissions reductions over carbon offsets in following a mitigation hierarchy. This alignment with different international instruments suggests that the Guidelines’ provisions on climate could gain enhanced normative legitimacy and wider uptake, as has been the case with the convergence of various international policy instruments around the UNGPs in the area of human rights noted above. Once again noting the importance of appropriate reporting, the Guidance also recognizes the need for regular reviews and updates of the adequacy of the GHG emissions reduction targets.Footnote 102

As previously noted, to date there are no recorded specific instances filed to NCPs concerning MNEs’ action or inaction regarding climate change adaptation. It is, therefore, welcome that one of the major changes in the 2023 Update has been the explicit incorporation of guidance on adaptation and resilience. Paragraph 79 of the commentary notes that ‘[e]nterprises should avoid activities, which undermine climate adaptation for, and resilience of, communities, workers and ecosystems’, and paragraph 77 suggests that enterprises should adopt science-based adaptation plans.Footnote 103 The focus on the possible impact on communities and workers from a lack of adaptation measures—for example in the case of climate-related flooding at a chemicals factory or oil terminal which could severely pollute the local area—is much needed. However, delays in the uptake of the necessary changes in practice by MNEs may well lead to controversies and the filing of new NCP complaints on this topic. It should be noted, however, that while the factual connection between a lack of action from MNEs and adverse human rights impacts is all too clear, it is likely that some of the challenges noted above regarding making integrated arguments on the human rights and climate aspects will also apply in this context. The exception may be that in the case of localized impacts caused by failures to adapt, the question of whether an MNE has caused or contributed to the harms suffered may be easier to establish.

V. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This article contributes to the literature on business and human rights, climate litigation and transnational business regulation by offering a conceptual framework for understanding corporate climate change responsibilities under the Guidelines. Over the years since the 2011 Update, there has been a significant shift in the understanding of corporate responsibility to reduce GHG emissions arising from business operations. This shift in the narrative is reflected in the evolving OECD jurisprudence. An analysis of the 14 climate-related complaints filed with NCPs prior to the 2023 Update reveals that these complaints primarily focused on emissions reduction obligations, with a particular focus on financial support for ongoing fossil fuel exploration and production. Yet these complaints mostly treat climate change as a discrete issue, overlooking the growing global recognition of its inherent linkage with human rights.

The 2023 Update marks an important step towards strengthening the role of the Guidelines in promoting corporate accountability for human rights and environmental abuses. The new provisions related to climate change and environment address some of the deficient areas that have been highlighted by the complaints. The Preface sets a clear intention of integrating climate and human rights, and it includes requirements for disclosing climate-related risks, conducting due diligence to prevent and mitigate adverse impacts of climate change, facilitating a just transition and ensuring climate resilience and adaptation. Nevertheless, the explicit integration of climate change in the scope of corporate human rights duties is not observed beyond the Preface. More clarity and guidance may be necessary, especially regarding the definitions of ‘cause’, ‘contribute’ and ‘linked to’ in the context of climate change.

The number of climate-related complaints referred to NCPs will doubtless increase, and new types of allegations within the scope of the expanded Guidelines are likely to arise. However, the effectiveness of the Guidelines in influencing business conduct will depend on their implementation through NCPs. Historically, poor enforcement and limited resources have been weaknesses in the Guidelines’ operation. Although the 2023 Update includes recommendations aimed at improving NCPs’ procedures, corporate implementation of the Guidelines and compliance with NCP decisions remains voluntary.Footnote 104

The 2023 Update firmly establishes the OECD's responsible business conduct regime as a component of the transnational regime complex for climate change. The Guidelines’ soft-law orientation has obvious limitations, but it does not diminish their potential significance. Nolan and McCorquodale emphasize the need for a multi-faceted approach to corporate accountability, integrating various tools such as litigation, regulatory measures and stakeholder engagement.Footnote 105 Although the OECD is a State-based organization, Abbott conceives of its Secretariat and officials as transnational actors who develop and administer norms such as the Guidelines and encourage private sector commitments. These standards could fill the gaps left by inter-State governance by bypassing multilateral gridlock and limited implementation capacity and by promoting norms, demonstrating their effects, and highlighting their shortcomings, thereby mobilizing political pressure on governments to take stronger climate action.Footnote 106 International soft-law instruments more easily achieve consensus and facilitate learning that may not be available through hard-law instruments,Footnote 107 and the Guidelines thus offer at least a starting point for international regulation of corporate climate impacts that might have otherwise remained elusive. This dynamic relationship between polycentric and binding governance serves to fill regulatory deficits in State-based regulation, provided it does not undermine or weaken the legitimate role of the State in regulating business.Footnote 108 In essence, the Guidelines serve as a valuable tool within the broader spectrum of corporate accountability mechanisms for addressing climate change and human rights. Their role is best understood as complementary to other legal and governance frameworks, working synergistically to advance responsible corporate behaviour and accountability on a global scale.

The significance of the Guidelines as a soft-law instrument should not, therefore, be understood as indicative of their sufficiency for ensuring corporate accountability and solving the global climate change challenge. The UNGPs—and by extension the Guidelines that incorporated them—were always intended as a starting point on which future norms could build and which could be further legalized over time.Footnote 109 It may be preferable for ‘loose alignment’ between such soft instruments and more binding legal instruments at subnational, national, regional and international levels, and the mere hardening of due diligence standards into legislation risks becoming a meaningless compliance exercise.Footnote 110 Litigation can be an important tool to identify gaps in both the Guidelines themselves and in existing legislation, and NCPs offer a unique mechanism for doing so because of their relatively low cost and high accessibility for adversely affected stakeholders. While NCPs’ limited enforcement capabilities and delegation from soft law can be seen as a weakness, scholars have also highlighted the significant limitations of domestic courts in holding transnational corporations accountable for human rights and environmental harm due to factors such as admissibility, language barriers, legal costs, time consumption, and countersuits from deep-pocketed corporations. Scholars therefore question whether hard or soft law can effectively achieve corporate accountability without States first reasserting their authority and grappling with corporate power.Footnote 111 Deva even questions whether the hardness or softness of international corporate accountability instruments is the most relevant question: instead of harder or softer norms, there is a need to consider more ambitious norms.Footnote 112 This thinking aligns with a growing number of calls from international relations and international law scholars who identify an overall dearth of climate-related (legal) norms and suggest that climate due diligence may be insufficient without also focusing on more promising and concrete norms such as fossil fuel bans.Footnote 113 NCPs’ new, clearer mandate to consider climate-related complaints could make them instrumental testbeds for informing the precise content of such future international legal norms.

As both OECD jurisprudence and the 2023 Update of the Guidelines move toward recognizing corporations’ responsibility to reduce emissions and to consider and disclose climate-related risks, other legal streams are also flowing in this direction, including climate lawsuits before courts and regulatory developments like the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive,Footnote 114 alongside increased investor action on climate-related risks. However, to remain relevant and effective, the 2023 Update must firmly establish the fundamental interlinkage between climate change and human rights through subsequent practice and interpretation by NCPs. This integrated approach could also inform the development and increasing ambition of international legal norms. Failure to do so may quickly render the 2023 Update outdated. Continued efforts in integrating climate change and human rights processes, possibly with additional guidance, will be essential for ensuring the Guidelines’ continued relevance and influence in shaping responsible corporate behaviour.

Acknowledgements

Ekaterina Aristova acknowledges financial support from the Leverhulme Trust under research project grant ECF-2021-132. Joana Setzer, Catherine Higham and Ian Higham acknowledge support from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science. The first draft of the article was presented in May 2023 at the workshop organized by the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg. The authors are grateful to organizers and participants for their feedback.