Conventional wisdom holds that the United States is the world's most litigious country. Media headlines scream about a “Litigious America” and its many “Bad Suits” and Americans seem convinced that “McDonald's Hot Coffee” cases are a frequent occurrence.Footnote 1 There are also frequent reports about the striking number of lawsuits filed each yearFootnote 2 and repeated complaints about the over-burdening of our court systems. Within sociolegal scholarship, the argument that people litigate readily has been called a “persistent myth” since most people do not pursue legal grievances (Reference EppEpp 2000; Reference GalanterGalanter 1983; Reference SilbeySilbey 2005), and the inaccuracy of the public's perception about litigation has been well documented (Reference EngelEngel 2016; Reference Haltom and McCannHaltom and McCann 2004). Still, scholars have devoted decades of study to understanding how, when, and why Americans initiate legal action.

Turning to a closer examination of when people frame a grievance as legal and when they pursue it, sociolegal scholars have argued from resources, (Reference GalanterGalanter 1974; Reference MietheMiethe 1995), the nature of the injury (Reference McDonald and PeopleMcDonald and People 2014; Reference Miller and SaratMiller and Sarat 1980−81; Reference Pleasence, Balmer and ReimersPleasence et al. 2011), and the “social meaning” attached to use of the legal system (Reference Albiston and SandefurAlbiston and Sandefur 2013: 104; Reference Felstiner, Abel and SaratFelstiner et al. 1980). Others have examined the characteristics of the parties themselves. Willingness to make a legal complaint in the United States varies by socioeconomic status, level of education (Access to Justice; Reference McDonald and PeopleMcDonald and People 2014), gender (Reference HoffmannHoffmann 2003; Reference MarshallMarshall 2003), and race (Reference MorrillMorrill et al. 2010; Reference Nielsen, McElhattan and WeinbergNielsen et al. 2017). The relationship between an injured person and the organization or person complained against also affects whether individuals resolve disputes via the legal system (Reference Berrey, Nelson and NielsenBerrey et al. 2017; Reference Felstiner, Abel and SaratFelstiner et al. 1980−81; Reference May and StengelMay and Stengel 1990; Reference Miller and SaratMiller and Sarat 1980−81; Reference MorganMorgan 1999; Reference YngvessonYngvesson 1984).

In this study, I build on these findings to examine whether women and men make different decisions about legal strategies, and whether relational distance is evident as a factor in decisions to complain in a legal institution. Pathbreaking studies have relied on observation and survey data; this study will evaluate findings via a survey using vignettes. The project separates legal action against a stranger, acquaintance, or close friend. Unlike most extant work, I also examine multiple stages of the litigation process (the decision to file suit, how to respond to a settlement offer, and whether to appeal a losing verdict), and disputes involving two different types of legal injuries. Gender does sometimes shape the decision making of potential plaintiffs, though it varies by the stage of litigation and the nature of the harm. Gender does not appear to interact with the plaintiff's connection to the potential defendant. This project gives us more insight into which individuals pursue legal action and, consequently, who does—and does not—undertake the risks and benefits of the legal system. It also illustrates how gender can shape the legal system in subtle, but still important ways.

The Decision to Litigate

Insights about relational distance contrast with frames relying on rational calculation and psychological biases. For those who work in the law and economics vein, choices about litigation can be understood as the consequence of litigants’ expected value calculations (Reference Priest and KleinPriest and Klein 1984; Reference Robbennolt, Zamir and TeichmanRobbennolt 2014). Given perfect and symmetrical information, litigants decide whether to settle cases or proceed to trial based upon which option provides the highest expected value (Reference Cooter and UlenCooter and Ulen 2012). Potential litigants, in other words, are rational actors whose choices are driven by strategic calculations (Reference BoydBoyd 2015; Reference Boyd and HoffmanBoyd and Hoffman 2012; Reference HyltonHylton 2000).

Psychological factors can shape calculations. Individuals can overestimate their chances for success, have biased perceptions about how much their injury is worth, and be overly confident in the likelihood of victory (Reference BabcockBabcock et al. 1995; Reference Moore and HealyMoore and Healy 2008; Reference Robbennolt, Zamir and TeichmanRobbennolt 2014). In addition, people's propensity for risk-taking (assumed by the standard economic model to be neutral or low) varies depending upon whether they are anticipating gains or losses (Reference Kahneman and TverskyKahneman and Tversky 1984): plaintiffs actually become more likely to take a chance at trial given a low probability of winning the case (Reference GuthrieGuthrie 2000). Interestingly, there is some evidence that these frames differ between men and women (Reference KimKim 2012; Reference UmphreyUmphrey 2003) and that women may evaluate gains and losses differently than men (Reference Harris and JenkinsHarris and Jenkins 2006).

Building from Felstiner et al.'s (1980–81) concept of “naming, blaming and claiming,” see, for example, Reference Berrey, Hoffman and NielsenBerrey et al. 2012, Reference Berrey, Nelson and Nielsen2017). Reference Nielsen, McElhattan and WeinbergNielsen et al. (2017) have argued that identifying the injury as potentially actionable (“naming”), identifying the party responsible for the injury (“blaming”), and demanding a legal remedy (“claiming”) depend on the individual's location in the social hierarchy. They suggest that members from marginalized minority groups will be more likely to recognize instances of racial discrimination but less likely to seek remedy through the legal system.

Scholars of legal consciousness are interested in dispute processing, particularly the “naming” and “blaming” stages (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey 1998; Reference HoffmannHoffmann 2003; Reference SilbeySilbey 2005). They emphasizes the importance of internal aspects of the individual such as emotion, principles and values, and psychological frames (Reference AbramsAbrams 2011; Reference HadfieldHadfield 2008; Reference MarshallMarshall 2003; Reference RelisRelis 2006; Reference Sandefur, Pleasence, Buck and BalmerSandefur 2007). More tangible traits such as income, education, and knowledge of the legal system also shape how individuals understand conflicts and whether or not they take legal action to resolve them (Reference Berrey, Hoffman and NielsenBerrey et al. 2012; Reference Genn and PatersonGenn and Paterson 2001; Reference McDonald and PeopleMcDonald and People 2014). Members of disadvantaged groups (such as the poor, women, and racial minorities) seem less likely to pursue legal remedies or claims of discrimination in particular, behavior which seems driven in part by their beliefs about the legal system's inability to understand and respond to their complaints (Reference BalmerBalmer et al. 2010; Reference BumillerBumiller 1988; Reference CoumarelosCoumarelos et al. 2012; Reference MorrillMorrill et al. 2010; Reference NielsenNielsen 2004; Reference Sandefur, Pleasence, Buck and BalmerSandefur 2007).

Gender, Litigation, and Relational Distance

When it comes to women in particular, we know some about how gender affects the use of the legal system. The strategic use of law by women's groups has received attention (Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor 1983; Reference Morton and AllenMorton and Allen 2001; Reference StrossenStrossen 1991). Multiple studies of sexual harassment show that gender shapes what disputes women consider worthy of formal resolution, with women much more likely to “lump it” rather than complain (Blackstone et al. 2000; Reference HebertHebert 2007; Reference MarshallMarshall 2003, Reference Marshall2005b; Reference MorganMorgan 1999; Reference QuinnQuinn 2000). Nielsen (2000) demonstrated how gender might shape perceptions of the use of law to combat street harassment. When confronted with a physical injury, women were less likely to file lawsuits than men and more likely to use more collaborative methods of dispute resolution such as mediation (Wofford forthcoming).

In this study, I suggest first that women will be more reluctant to use formal legal procedures such as a lawsuit to resolve a dispute. Litigation is an inherently adversarial, risky, and competitive process. At the most basic level, it involves two parties engaged at cross-purposes, competing and clashing over whose legal claim will prevail. There are certain procedural rules that promote information sharing and may funnel the litigants towards agreement, but the process inevitably involves some argument, conflict, and confrontation.

Yet women tend to avoid competition and conflict (Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach 1994; Reference MorganMorgan 1999). Women are more likely to avoid competitive situations (Reference Booth and NolenBooth and Nolen 2009; Reference Gneezy, Leonard and ListGneezy et al. 2009) and withdraw earlier than men from competitive environments (Reference Hogarth, Karelaiab and TrujilloHogarth et al. 2012).

Women may see the process of dispute resolution, moreover, as proceeding best through communication and compromise, in which the positions of both sides are deemed reasonable and worthy of accommodation (Reference BartlettBartlett 1990; Reference Menkel-MeadowMenkel-Meadow 1985). Such behavior has been suggested for female officeholders, for example, who are expected to “emphasize… compromise, consensus building, and cooperation” (Reference Reingold, Wolbrecht, Beckwith and BaldezReingold 2008: 132), as compared to men's skills in “personal assertiveness and competition” (Reference RosenthalRosenthal 2000: 25). Women, in other words, may be more collaborative than men, preferring cooperation over coercion and control (Reference Burke and CollinsBurke and Collins 2001; Reference GilliganGilligan 1982; Reference ThomasThomas 1994; but see Reingold 1996, Reference Reingold2000).

When it comes to resolving a disagreement or conflict, women are thought to seek inclusive solutions that “make everybody happier” rather than framing the issue as “no-holds barred contest” with winners and losers (Reference GilliganGilligan 1982; Reference MorganMorgan 1999: 70; see also Reference SherrySherry 1986). Studies of negotiations in the legal, political, social, and family contexts have born this out, with scholars finding that women…. “understand control through empowerment, and problem-solving through dialogue” (Reference BoyerBoyer et al. 2009; Reference Kolb, Coolidge, Breslin and RubinKolb and Coolidge 1991: 62; Reference Legerski and CornwallLegerski and Cornwall 2010; Reference Nadler and NadlerNadler and Nadler 1986; Reference SumoskiSanchez 1994; Sumoski 2001; but see Reference CraverCraver 2002). Female jurists also encourage more negotiation between the parties and promote settlements more than their male counterparts (Reference BartlettBartlett 1990; Reference BoydBoyd 2013; Reference Brown, Parmet and O'ConnellBrown et al. 1999).

Women also are more risk-averse then men. Studies in economics (Reference Charness and GneezyCharness and Gneezy 2012; Reference Eckel and GrossmanEckel and Grossman 2008; Ertac and Gurdalb 2012), psychology (Reference Byrnes, Miller and SchaferByrnes et al. 1999; Reference CampbellCampbell 2002; Reference Harris and JenkinsHarris and Jenkins 2006), and law (Reference Adhikari, Agrawal and MalmAdhikari et al. 2015; Reference Craver and BarnesCraver and Barnes 1998; Reference MorganMorgan 1999) have found that women are less likely to take risks than men. In politics, female candidates also appear to evaluate the risks of running for elected office differently than men; their lower political ambition has been attributed in part to greater risk aversion (Reference Lawless and FoxLawless and Fox 2012; Reference MaestasMaestas et al. 2006).

Despite this extensive literature, we do not know if these findings apply to women's choices about litigation in particular. Data on women's resistance to competition come from experiments using artificial games such as solving paper mazes and tossing a tennis ball into a bucket (Reference Booth and NolenBooth and Nolen 2009; Reference Gneezy, Leonard and ListGneezy et al. 2009), arenas with much lower stakes than the legal system. Studies of compromise in the home and political negotiations are more analogous, as they involve two parties disputing over limited resources (Reference BoyerBoyer et al. 2009; Sanchez 1994), but we have yet to explore whether the behavior manifests in the more structured, formalized legal process. The findings on women's risk-taking sample from very unique populations such as corporate leaders (Reference Adhikari, Agrawal and MalmAdhikari et al. 2015), students at elite schools (Reference Craver and BarnesCraver and Barnes 1998; Reference Harris and JenkinsHarris and Jenkins 2006), and potential political candidates (Reference Lawless and FoxLawless and Fox 2012); “ordinary” women's preference for risk may differ.

In sum, women may approach litigation differently than men. If women have an aversion to conflict, competition, and risk that does persist in the legal context, then their choices about whether to pursue litigation and whether and how to resolve it once started may diverge sharply from their more combative male counterparts. At the same time, the lack of data on the litigation choices of both sexes generates substantial space to explore if women's decisions about the legal process are gendered.

This study also assesses the impact of the relationship between the potential plaintiff and defendant. In assessing arrest rates, Reference Black, Sanders and DaudistelBlack (1976) labeled this the “principle of relational distance” which he measured by the frequency of interaction, degree of interdependence, and number of dimensions along which interactions between parties occur. In terms of law more generally, the idea is that the greater this distance (the less intimate the parties), the more likely they are to employ formal and public procedures to resolve the dispute; the shorter this distance (the closer the parties) the less likely they are to end up in court.

“Relational distance” does seem to shape litigation choices. Litigation rates rise when there is no future relationship between the plaintiff and defendant (Reference MacaulayMacaulay 1963). Individuals in ongoing or closer relationships also are less likely to pursue legal action, across a range of contexts and circumstances (Reference EngelEngel 1984; Reference Hamilton and SandersHamilton and Sanders 1992; Reference Lempert and SandersLempert and Sanders 1986; Reference MullisMullis 1995; Reference SaratSarat 1976; Reference SilbermanSilberman 1985; see also Reference GalanterGalanter 1983). The theory holds for interest groups as well (Reference Morag-LevineMorag-Levine 2003).

Further study is needed as to how gender shapes individual litigation strategies and whether relational distance affects male and female litigants differently. There has been relatively little work on how gender shapes decisions about litigation and no studies (of which I am aware) of whether a plaintiff's gender interacts with the nature of the relationship with the defendant.

Decisions about litigation may be affected by the nature of the relationship between the litigant and potential defendant, with male and female litigants responding differently depending upon the identity of the opposing party. If women are making distinctive choices about if and how to employ the legal system, however, than the cases which ultimately become the “raw material” for judicial policy making have been gendered. In addition, if women's choices are motivated by considerations about relationships in a way that men are not, the population of citizens who take advantage of the benefits of a formal legal process is not gender-neutral and has been affected by psychological and social forces.

I theorize that women's general reluctance to pursue litigation will be compounded when there is less relational distance between themselves and their potential opponent. There are several reasons why gender might interact with relational distance in this way.

Originating in the field of psychology (Reference GilliganGilligan 1982; Reference LarrabeeLarrabee 1993; Reference NoddingsNoddings 2003), the notion that relationships with others are fundamental to women and women's lives has appeared in other subfields as well (see e.g., Abrahms 2011). Though this “connection thesis” (Reference WestWest 1988) has been widely criticized as essentialist (see e.g., Reference CainCain 1988; Reference CrenshawCrenshaw 1995), it has shown empirical grounding in studies of conflict resolution and negotiation. Reference Babcock and LacheverBabcock and Lachever (2003), for example, posit that women possess a distinctive “self-schema” in which their sense of interdependence with the other party shapes how they approach negotiations (see also Reference Calhoun and SmithCalhoun and Smith 1999). Reference BoyerBoyer et al. (2009) demonstrated that in international negotiations, women are more interactive with their negotiation partners and employ more collaborative methods of dispute resolution than their male counterparts.

We know very little about whether these gender differences are applicable or manifest themselves when individuals are considering whether and how to pursue legal action. The work that does exist has focused primarily on sexual harassment. Reference MorganMorgan (1999), for example, finds that women's concerns for personal relationships and family—the “nature and complexity of the relational web within which [she] lives her life”—are central factors in the decision to pursue claims of sexual harassment, with relationships being both a detriment and incentive to reporting the injury (see also Reference Blackstone, Christopher and McLaughlinBlackstone et al. 2009). Women's concern for consequences and retaliation that may ensue from a sexual harasser at work may also augment their reluctance to file claims of sexual harassment (see e.g., Reference Fitzgerald, Swan and FischerFitzgerald et al. 1995; Reference WrightWright 2007).

While there have been many studies assessing the role of relationships in the decision to litigate, there has been insufficient attention to the plaintiff–defendant relationship in particular, how that relationship affects legal actions beyond the initial choice to sue, and what role gender might play. More precisely, we do not know if a women's relationship with the potential defendant will also have a disproportional impact upon her decisions about whether and how to use the legal process, in all its stages. Using the concept of “relational distance,” I posit here that while both men and women might be more reluctant to pursue a formal legal process against someone they know, a female litigant will be even more reluctant to pursue and/or continue with litigation if she has a preexisting personal or professional relationship with the potential defendant. In such instances, her desire to maintain the bond and preserve positive feelings between herself and the other party should further dampen her desire to file a lawsuit.

Thus, I hypothesize:

H1: Female litigants will be less likely than male litigants to institute a legal claim as the relational distance from the potential defendant decreases.

Once litigation has begun, a woman also should be more likely than a man to pursue resolutions outside the formal structure of the courtroom. This could include mediation or other forms of alternative dispute resolution (ADR)Footnote 3 which are designed to promote conflict resolution through dialogue and achieve solutions which are satisfactory to both parties. Thus, I hypothesize:

H2: Having begun litigation, female litigants will be more likely than male litigants to pursue alternative dispute resolution as the relational distance from the defendant decreases.

Similarly, if given a reasonable settlement offer from someone they know well, a woman should be more likely to agree to it than a male in a similar situation.Footnote 4

H3: Female litigants will be more likely than male litigants to agree to settle a case as the relational distance with the defendant decreases.

The Litigation of Pay Discrimination

If the case involves pay discrimination, the interaction between relational distance and gender may operate differently. Females may make different choices about legal action in such cases depending upon the extent of their relationship with the potential defendant. How so? One the one hand, women may be more aggressive in their legal strategy than men. Female legislators are more active and assertive when it comes to certain “women's issues,” particularly at the agenda-setting stage (Reference Cammisa and ReingoldCammisa and Reingold 2004; Reference Carroll and CarrollCarroll 1984, 2001; Reference SwersSwers 2002; Reference ThomasThomas 1994). If potential litigants behave similarly, then we might expect females in pay discrimination cases to be more likely to sue and prefer more adversarial methods of dispute resolution.

At the same time, women are more likely to experience sex-based discrimination and recognize it as potentially actionable (Reference Blackstone, Christopher and McLaughlinBlackstone et al. 2009) or know of other women who have pursued legal resolution from whom they can seek information and support. Men may also feel more uncomfortable bringing a discrimination claim into the very public arena of a courtroom.

On the other hand, when the relationship with the potential defendant is incorporated, women's strategic calculations about litigation may differ. In particular, I suggest here that any eagerness they have for the adversarial process in this type of case will be counter-balanced, if not outweighed, by the considerations about their connection to the defendant.

As noted above, relationships can be particularly important to women. If they have had regular and pleasant personal interactions with the opposing party, the pressure to be “nice” and to maintain the good feelings and “interpersonal harmony” (Reference MorganMorgan 1999: 88) in the relationship could dissuade their pursuit of legal action. Given that women who are proactive in the arena of women's rights are often tagged with the now-derisive label of “feminist” or even “bit-h” (Reference AndersonAnderson 1999; Reference AronsonAronson 2003; Reference Burn, Aboud and MoylesBurn et al. 2000; Reference OlsonOlson et al. 2008; Reference RahmanRahman 2015), a female might be especially reluctant to bring suit over this type of case knowing that the opponent–whom she might know quite well—could invoke these terms against her.

If a female expects future interactions with the defendant, moreover, she may be especially concerned that their connection remains free of conflict, particularly over “hot” or potentially embarrassing topics such as sex discrimination. She also may fear retribution, as women often do when considering whether to report sexual harassment (Reference MorganMorgan 1999), or know that sex discrimination claims are often unsuccessful (Reference Berrey, Nelson and NielsenBerrey et al. 2017; Reference Hoyman and StallworthHoyman and Stallworth 1986; Reference StambaughStambaugh 1997). These consequences might be particularly painful to experience when the retribution or defeat in court involves someone she knows. In short, I suggest that the closer a woman is to the potential defendant, the more likely she will be to avoid the face-off of the standard adversarial process offered by litigation.

Thus, I hypothesize:

H4: When confronted with a potential legal dispute involving pay discrimination, female litigants will be less likely than male litigants to institute a legal claim as relational distance decreases.

H5: Having begun litigation, female litigants will be more likely than male litigants to pursue alternative dispute resolution in a case involving pay discrimination as relational distance decreases.

H6: Having begun litigation, female litigants will be more likely than male litigants to agree to settle a case involving pay discrimination as relational distance decreases.

Data and Methods

The data for the study come from an anonymous online survey of 629 respondents, conducted by Qualtrics, Inc. Qualtrics is a software company that allows users to develop and implement web-based surveys; the company builds a panel of respondents based upon criteria set by the user. It offers several advantages over non-commercial surveys (Reference Boas and HidalgoBoas and Hidalgo 2013) and other methods such as mail surveys or personal interviews (Reference Heen, Lieberman and MietheHeen et al. 2014). It has also become increasingly popular, particularly for experimental research designs (see e.g., Johnson et al.; Reference Kahan, Jenkins-Smith and BramanKahan et al. 2011; Reference Kriner and ShenKriner and Shen 2012; Reference Simon and ScurichSimon and Scurich 2011).

Request was made for a sample of 600 respondents that matched the U.S. population in terms of gender, income, and race, with additional attention paid to age and education. To ensure the sample matched the general population on these parameters, the panel number was later raised to 629.

The final sample reflected the overall population on these measures reasonably well, with 51.23 percent female (compared to 50.9 percent in the U.S. population), 70.26 percent white (versus 77.1 percent in the U.S. population) and a median income of approximately $52,000 (vs. $53,889 for the U.S. population). Since minors cannot institute legal action on their own behalf, the panel excluded those who were under the age of 18. It also excluded individuals who indicated they were not fluent in English and those residing outside the United States.

After answering a series of questions about their age, gender, education, income, political ideology, and employment, respondents were first randomly presented with one of three scenarios in which they confronted a situation that could warrant legal action. One hundred ninety-nine respondents viewed the first scenario, 214 viewed the second, and 216 viewed the third.

Each vignette was designed to contain a potentially common legal dispute, involving a generic “slip and fall” accident. The vignettes differed, however, in the identity of the opposing party. In the first, it is a large “faceless” company; in the second, it is an “acquaintance” shop owner; and in the third, it is a close friend and neighbor.

The precise wording of the vignettes are as follows:

Vignette #1: Imagine that you are shopping at a large “big box” retail store. As you walk down an aisle, you see a sign indicating that the floor is wet, so you step around a nearby puddle. After you walk several more feet, you slip in a second puddle, falling to the ground. You visit your doctor and learn that you have sustained damage to several disks in your spine and will need expensive surgery to correct the problem. Your health insurance company has refused to pay the claim, stating that it is the store's responsibility. The store claims that you did not follow their signs and should have avoided the area entirely. Assume that the cost of taking action is not a concern to you. If this happened to you, what would you do?

Vignette #2: Imagine that you are getting your regular cup of coffee at your favorite, locally owned coffee shop. You have had multiple brief but pleasant interactions with the owner and consider the owner to be an acquaintance. After purchasing your coffee, you see a sign indicating that the floor is wet, so you step around a nearby puddle. After you walk several more feet, you slip in a second puddle, falling to the ground. You visit your doctor and learn that you have sustained damage to several disks in your spine and will need expensive surgery to correct the problem. Your health insurance company has refused to pay the claim, stating that it is the coffee shop owner's responsibility. The shop owner claims that you did not follow the signs and should have avoided the area entirely. Assume that the cost of taking action is not a concern to you. If this happened to you, what would you do?

Vignette #3: Imagine that you are visiting your long-time neighbor, who also has been your very close friend for the past several years. As you are walking through your friend's kitchen, the friend tells you to avoid a puddle on the floor near the sink, which you do. After you walk several more feet, you slip in a second puddle on the floor, falling to the ground. You visit your doctor and learn that you have sustained damage to several disks in your spine and will need expensive surgery to correct the problem. Your health insurance company has refused to pay the claim, stating that it is your friend's responsibility. Your friend claims that you did not listen carefully and should have avoided the area entirely. Assume that the cost of taking action is not a concern to you. If this happened to you, what would you do?

In addition, respondents were also randomly assigned to read one of three vignettes in which the respondent learns that he or she may be the victim of sex-based pay discrimination.Footnote 5 Each of these three vignettes also varied the nature of the defendant to capture a sense of “stranger,” “acquaintance,” or “friend.” This was done by varying the size of the employer company that has discriminated as well as the number of interactions the respondent has had with the head of the company. Two hundred respondents viewed the first vignette, 219 viewed the second, and 210 viewed the third from this set.

The precise wording of these vignettes is as follows:

Vignette #4: Imagine that you have worked happily at a very large company (over 10,000 employees) for over ten years. You recently learned, however, that a person of the opposite sex does basically the same job as you do, but is paid a lot more. You report your concerns to a supervisor at the company's headquarters, which is located across the country. You have never met or spoken with the supervisor before this. The supervisor says all salary matters are confidential and cannot be discussed. Assume that the cost of taking action is not a concern to you. If this happened to you, what would you do?

Vignette #5: Imagine that you have worked happily at a mid-size company (around 50 employees) company for over ten years. You recently learned, however, that a person of the opposite sex does basically the same job as you do, but is paid a lot more. You report your concerns to your supervisor, who also owns the company. Your supervisor is an acquaintance of yours and you have worked together several times over the past ten years. The supervisor says all salary matters are confidential and cannot be discussed. Assume that the cost of taking action is not a concern to you. If this happened to you, what would you do?

Vignette #6. Imagine that you have worked happily at a very small (less than 5 employees) company for over ten years. You recently learned, however, that a person of the opposite sex does basically the same job as you do, but is paid a lot more. You report your concerns to your supervisor, who also owns the company. Your supervisor is a close friend of yours and you have worked together frequently over the past ten years. The supervisor says all salary matters are confidential and cannot be discussed. Assume that the cost of taking action is not a concern to you. If this happened to you, what would you do?

After each vignette, I gave respondents four options designed to evaluate what initial decision they would make in this situation.Footnote 6 The options were:

1. File a lawsuit Footnote 7;

2. Use a third-party mediator who would work with you and the [store/company/person] to try and find common ground and resolve the dispute;

3. Try to resolve the dispute outside the legal system (for example, through an informal meeting);

4. Do nothing.

I call this stage of the decision-making process “Stage One.”

For those respondents who said they would pursue litigation, I then described a situation in which they were presented with a settlement offer by the defendant. The text is as follows:

Vignette #1: Imagine now that you file the lawsuit. A few weeks later, the store's attorney contacts your attorney and offers you a substantial sum of money, which will cover the cost of surgery and compensate you somewhat (but not completely) for your injuries, if you agree to end the lawsuit. Assume that the cost of taking further action is not a concern to you. Which of the following courses of action would you take?

Vignette #2: Imagine now that you filed the lawsuit. A few weeks later, the shop owner's attorney contacts your attorney and offers you a substantial sum of money, which will cover the cost of surgery and compensate you somewhat (but not completely) for your injuries, if you agree to end the lawsuit. Assume that the cost of taking further action is not a concern to you. Which of the following courses of action would you take?

Vignette #3: Imagine now that you filed the lawsuit. A few weeks later, your friend's attorney contacts your attorney and offers you a substantial sum of money, which will cover the cost of surgery and compensate you somewhat (but not completely) for your injuries, if you agree to end the lawsuit. Assume that the cost of taking further action is not a concern to you. Which of the following courses of action would you take?

Vignette #4: Imagine now that you did file the lawsuit. A few weeks later, the attorney for the company contacts your attorney and offers to increase your salary to that of the other employee but not pay you any of the back pay you feel you are owed. Assume that the cost of taking further action is not a concern to you. Which of the following courses of action would you take?

Vignette #5: Imagine now that you did file the lawsuit. A few weeks later, the attorney for the company contacts your attorney and offers to increase your salary to that of the other employee but not pay you any of the back pay you feel you are owed. Assume that the cost of taking further action is not a concern to you. Which of the following courses of action would you take?

Vignette #6: Imagine now that you file the lawsuit. A few weeks later, the attorney for your friend's company contacts your attorney and offers to increase your salary to that of the other employee but not pay you any of the back pay you feel you are owed. Assume that the cost of taking further action is not a concern to you. Which of the following courses of action would you take?

Respondents were then instructed to select one of the following four options:

1. Refuse the offer and continue with the lawsuit;

2. Accept the offer and end the lawsuit;

3. Continue with the lawsuit but use a third party mediator who would work with you and the defendant to try to find common ground and resolve the dispute;

4. Stop the lawsuit and try to resolve the dispute outside the legal system (for example, through an informal meeting).

I call this stage of the decision-making process “Stage Two.”

Results—Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics show interesting, though somewhat unexpected findings about the litigation choices of men and women. Tables 1 and 2 display the percent of male and female respondents who made each litigation decision, and the difference between the two groups for the three “slip and fall” vignettes. Tables 3 and 4 contain similar results for the pay discrimination vignettes.

Table 1. Comparing Legal Strategies of Men and Women. Stage One, “Slip and Fall” Injury

Table 2. Comparing Legal Strategies of Men and Women. Stage Two, “Slip and Fall” Injury

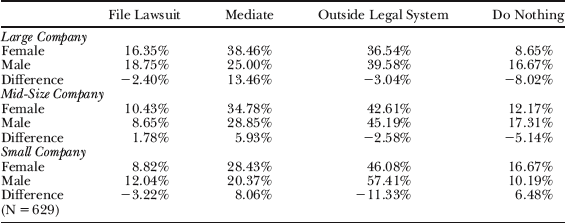

Table 3. Comparing Legal Strategies of Men and Women. Stage One, Pay Discrimination

Table 4. Comparing Legal Strategies of Men and Women. Stage Two, Pay Discrimination

“Slip and Fall” Injury

First, in the “slip and fall” cases, women appear to be less openly litigious than men. Regardless of the nature of the relationship with the defendant, women were consistently less likely than men to file suit (12.05 percent less likely with a stranger; 4.21 percent less with an acquaintance; 4.27 percent less likely with a friend). Only the first difference (suit against a stranger) was statistically significant, however, at p < .01.Footnote 8

Female respondents also showed a consistent preference for mediation, at least during Stage One of the process. As seen in the “mediate” columns of Table 1, a greater percentage of women than male respondents always chose mediation as their first response to the dispute, though the difference only reached statistical significance (p < .05) when confronting a friend as defendant.

When it comes to the impact of the relationship between the respondent and potential defendant, the interaction with gender is minimal. Both men and women were less likely to sue individuals as their relational distance decreased. Men's probability of a lawsuit dropped from 39.4 percent against a stranger, to 30.3 percent against an acquaintance, to 12.3 percent against a friend; women's probability of filing suit also dropped: from 27.36 percent against a stranger, to 26 percent against an acquaintance, to 8.10 percent against a friend.

These data show little support for Hypothesis 1 in particular. Contrary to expectations, for example, women were 19.26 percent less likely to sue a friend than a stranger but men were 27.1 percent less likely to sue a friend versus a stranger. Similarly, women's probability of suing a stranger versus an acquaintance dropped only 1.36 percent whereas men's declined 9.1 percent. According to these results, then, it is actually men who are more reluctant to file suit against those whom they have a more intimate relationship.

When deciding how to respond to a settlement offer once litigation has begun (Stage Two), there is mixed support for Hypothesis 3. As seen in Table 2, women were more likely than men to agree to settle cases against a stranger and a friend (though the differences were not statistically significant). They were not less likely to agree to settle in the dispute against an acquaintance.

In terms of percentages across relational distance, men were most willing to settle against an acquaintance (43.33 percent) followed by a stranger (26.82 percent) and then a friend (23.07 percent). For women, the pattern was generally similar, with rates of willingness to settle at 41.66 percent against the stranger, 26.26 percent against the acquaintance, and 33.33 percent against a friend. It seems at least from this data that the concept of relational distance generally does not apply to the settlement behavior of women or men. The only exception is that women were more slightly willing to settle against a friend than an acquaintance, though the 7 percent difference was not statistically significant.

Yet when we look at the legal strategy of mediation in Stage Two, relational distance does behave as predicted in Hypothesis 2. As seen in the “mediate” column of Table 2, the closer a female respondent was to a potential defendant, the more likely she was to choose mediation in response to a settlement offer: 19.23 percent opted for mediation against stranger, 36.67 percent when confronting an acquaintance, and 44.44 percent when considering a settlement offer from a friend. The male respondents answered less consistently, with a choice of mediation at 36.59 percent against the stranger, 16.66 percent against the acquaintance, and 38.46 percent against the friend.

To put it differently, while both men and women were most likely to favor mediation with the friend, only the female respondents were increasingly drawn to mediation as their relationship with the potential defendant became closer. However, so few respondents reached Stage Two in the vignettes, particularly when the potential defendant was a friend (N = 41 men; 26 women for Vignette #1; N= 30 men; 30 women for Vignette #2; N = 13 men; 9 women for Vignette #3), that the conclusions are not reliable.

Pay Discrimination

Tables 3 and 4 display the results for the second set of vignettes, in which the potential plaintiff faced a problem of pay discrimination by a large, mid-size, and small company.

Several of these results are similar to those in the “slip and fall” case. Women appear at first glance to be somewhat less litigious than men. As seen in Table 3, women were 2.4 percent less than men likely to sue a large company and 3.2 percent less likely than men to sue the small company; they were slightly more likely (1.7 percent), however, to file suit against the mid-size company. This latter difference was the only one to reach statistical significance (p < .05).

As with the first set of vignettes, women again show greater preference for mediation than men in Stage One of the process. Against the large company, almost 40 percent of women (versus 25 percent of men) opted for mediation, a statically significant difference of 13.5 percent (p < .05). Women were 5.9 percent more likely than men to choose to mediate against a mid-size company and 7 percent more likely to do so against the small company, though neither of these differences were statistically significant.

When it comes to the impact of relational distance, the data support Hypothesis 4. Female respondent's willingness to file suit declined as relational distance increased: 16.53 percent would sue the large company, 10.43 percent the mid-size company, and 8.82 percent the small company. Almost 19 percent of male respondents would sue the large company, 10.43 percent would sue the mid-size company, but 12.04 percent indicated they would sue the small company owned by their close friend.

Hypothesis 5 predicted that, once litigation had begun and a settlement offer had been made, women would be more likely than men to opt for mediation as relational distance decreased. Table 4 shows that while women did favor mediation at higher rates than men against the large and medium company (58.82 percent vs 27.78 percent and 16.67 vs 11.11 percent, respectively), the rates were virtually identical against the small company (23 percent of men; 22 percent of women).

Moreover, women were not more likely to mediate as relational distance grew – in fact, they were most likely to opt for mediation against the large company, followed by the small and mid-size companies. Interestingly, men showed the same inconsistency, favoring mediation most with the large company, followed by the small, followed by the mid-size company. Both genders, in other words, seemed similarly (dis)affected by relational distance.

There is also mixed support for Hypothesis 6. Women were more likely than men to accept a settlement offer from a small or mid-size company once litigation has begun, but not against the large company. In fact, none of the 17 women suing the large company would accept the settlement offer (7 kept going with the suit while 10 opted for mediation).Footnote 9 Against the mid-size company, 50 percent of the women versus 44.44 percent of the men agreed to settlement; against the small company, the difference was even more marked (and statically significant) with 33.33 percent of women and 15.38 percent of men agreeing to settle the case.

These results show, however, that women were not more likely to accept settlement as relational distance increased—they were least likely to settle against the large company, but most likely to settle against the mid-size company. Moreover, they were not more likely than men to do so as the distance increased. Women's consent to settlement dropped 23 percent from the medium to small company, but men dropped slightly more, at 29 percent.

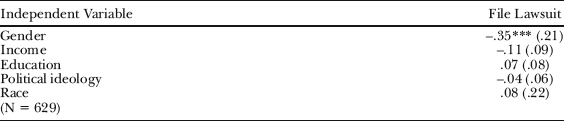

Results—Multivariate Models

To determine if any of these findings persisted when accounting for other variables, I also conducted a multivariate analysis. Respondents were given multiple options for their responses to survey questions, but I was primarily interested in whether they would litigate or not, mediate or not, and settle or not, as articulated in the hypotheses. I therefore constructed the following as dependent variables: for Stage One (the initial decision about whether and how to take legal action), the dependent variable was whether or not the respondent filed suit in any of the vignettes. For Stage Two (the response to a settlement offer), the dependent variables were whether or not respondents chose to mediate or agreed to settle any of the disputes contained in the vignettes. This approach to the dependent variable comported better with the study's theory and allowed comparisons of the particular choice against all other options, rather than each against one base outcome.Footnote 10 Given the dichotomous nature of the three dependent variables (1 if yes, 0 if no), a logit model with robust standard errors was employed.

The primary independent variable is the interaction between the gender of the respondent (coded 0 for male and 1 for female) and the nature of the potential defendant (stranger, acquaintance, friend). This interaction term was created by coding a new variable to capture relational distance, coded 1 for stranger, 2 for acquaintance, and 3 for friend. I then interacted this variable with the gender of the respondent. As each respondent was randomly assigned to one vignette from each of the two sets of vignettes, I calculated the relational distance and interaction term separately and ran separate statistical models for each group.

Decisions about adjudication may also be affected by other individual-level traits, so I included several controls. First, those with higher socioeconomic status may make decisions about litigation differently than those of lower socioeconomic status. Individuals with higher incomes and education likely have more knowledge about the legal system or may have others in their social networks who can help them navigate the litigation process. Higher SES individuals also may have more internal efficacy, a belief that they have the requisite skills and know-how to deal with the complexities of courts. As a result, they may feel more comfortable using the legal system. I therefore account for the respondent's annual income and level of education.Footnote 11 Respondent's ideology may also play a role, with liberals more willing to use government institutions such as courts. The model thus includes a variable for political ideology.Footnote 12

Racialized minorities mistrust the legal system more than whites (Reference AndersonAnderson 2014; Reference Longazel, Parker and SuLongazel et al. 2011; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler and Huo 2002). Studies have focused on the criminal justice system, but this mistrust may extend to the civil court system as well (but see Reference Nielsen, McElhattan and WeinbergNielsen et al. 2017). Therefore, racialized minorities could be less likely than whites to pursue litigation, more likely to pursue remedies outside the legal system, and less likely to pursue appeals (Reference GreeneGreene 2016; Reference MorrillMorrill et al. 2010). Accordingly, I include a dichotomous variable indicating whether respondents are minority (1) or white (0).Footnote 13

“Slip and Fall” Injury

Tables 5-8 present the results from the multivariate analysis.

Table 5. Logit Model, “Slip and Fall” Injury (No Interaction)

Table 6. Logit Model, “Slip and Fall” Injury

*p value < .1; **p value < .05; ***p value < .01.

Table 7. Logit Model, Pay Discrimination (No Interaction)

a *p value < .1; **p value < .05; ***p value < .01.

Table 8. Logit Model, Pay Discrimination

a *p value < .1; **p value < .05; ***p value < .01.

When it comes to the Stage One of legal decision making process, it is worth noting first that women sometimes appear less likely to litigate, at least when the nature of the relationship with the defendant (as captured by the interaction term) is not included in the model. As seen in Table 5, when confronting the generic dispute, the variable for gender reaches significance at p < .01 and is signed in the negative direction, indicating women would be less likely than men to file a lawsuit in response to the “slip and fall” injury. There were no statistically significant gender differences in mediation or settlement behavior.

When the relationship between gender and relational distance is incorporated, the results show no consistent differences between the litigation propensities of men and women across relational distance. As seen in the first column of Table 6, the interaction terms fail to reach statistical significance.Footnote 14 The data, in other words, provide little support for Hypothesis 1's prediction that women would be less likely than men to litigate as their personal relationship with the defendant grew closer.

Regarding the response to a settlement offer (Stage Two), the results are again contrary to expectations. As seen in the second column of Table 6, the interaction variable fails to reach statistical significance when the dependent variable is agreeing to settlement, failing to support hypotheses 3. For the second dependent variable—the decision to choose mediation—the p value only reaches .1. In other words, once a settlement offer has been made, the responses of male and female respondents did not differ in any meaningful way.

Notably, minorities were less likely to settle the “slip and fall” cases than whites.Footnote 15 They were no more or less likely than whites to file a lawsuit or opt for mediation once litigation had commenced.

Pay Discrimination

When confronting the issue of pay discrimination, some of the results contrast those above. Without accounting for relational distance, women were no more or less likely than men to litigate during Stage One of the process.Footnote 16 Table 7 shows this result.

When the interaction with relational distance is included, there are again no significant findings, at least during Stage One. As seen in the first column of Table 7, the interaction term does not reach statistical significance, providing no support for Hypothesis 4. Interestingly, those with more education and who were more liberal were actually less likely to file suit. Minorities seem slightly more likely to initiate litigation, though the variable only reaches marginal significance (p < .1).

When examining Stage Two of the legal process—how plaintiffs respond to settlement offers, the findings are more favorable, but mixed.Footnote 17

Regarding whether or not to favor mediation, the results in the third column of Table 8 show that the interaction terms is not significant. However, as Reference Brambor, Clark and GolderBrambor et al. (2006) reminds us, lack of significance on an interaction indicates only that the slopes of the interaction and non-interaction terms did not differ from zero, not that they did not differ from each other. I therefore calculated predicted probabilities (holding all other variables at their means) as gender shifts from 0 (men) to 1 (women) across relational distance.

Figure 1 shows that women were 42 percent more likely than men to favor mediation against the large company, 43 percent against the mid-size company and 39 percent more likely than men to favor mediation against the small company. This suggest that women are consistently—and much more—likely than men to favor mediation once litigation has begun. It also shows, however, that their willingness to do so does not vary much by relational distance.

Figure 1. Predicted Probability of Selecting Mediation, By Gender and Relational Distance—Pay Discrimination Cases.

When it comes to whether respondents agree to settlement offers, women were less likely to agree to settle than men as relational distance declined. Here, the interaction term was significant (p < .05). As seen in Figure 2, the predicted probabilities (calculated holding all other variables at their means) demonstrate that women were 38 percent less likely than men to settle against the large company, 27 percent less likely than men to do so against the mid-size company, and 19 percent less likely than men against the small company. This finding contrasts the prediction that women, even when facing discrimination, would be more likely to settle complaints against defendants whom they knew well.

Figure 2. Predicted Probability of Agreeing to Settle, By Gender and Relational Distance—Pay Discrimination Cases.

Discussion

This study has uncovered several notable patterns in the litigation choices of both men and women. Perhaps most striking is how infrequently respondents, regardless of gender, ever chose to file suit at all. Although the finding is surprising in the context of media reports, it is entirely consistent with sociolegal scholarship demonstrating people's reluctance to file suit. Indeed, across every situation presented to respondents, filing a lawsuit was never the most popular choice. In fact, with the exception of “slip and fall” in the “big box” store, bringing suit was always the third most popular option, followed only by taking no action at all. Instead, respondents opted for either mediation or resolution of the dispute outside the legal system. This means that respondents were not willing to accept their injuries without recourse, but that their preferred method of resolution only rarely included the initiation of litigation. Contrary to conventional wisdom, ordinary individuals simply do not seem to be especially litigious.

The finding about the reluctance to file suit persists even though the vignettes advised respondents they need not be concerned with the cost of litigation.Footnote 18 In reality, the cost of filing a lawsuit is surely a consideration and likely often prohibitive. Given all this, when we consider that both of these vignettes involved serious and legally cognizable harms, there were a very large number of lawsuits that could have been filed, but were not. If the respondents in this survey are any indication, Americans rarely use courts for resolution of their personal and professional problems.

Second, the nature of the injury seems to affect whether or not respondents bring a case into the legal system at all. More precisely, both men and women were usually very reluctant to bring the issue of pay discrimination to court. Against the large corporation, only 16.35 percent of women and 18.75 percent of men opted for suit over pay disparity, compared to 27.37 percent of women and 39.42 percent of men who would sue over the “slip and fall” injury. Against the mid-size corporation, 10.43 percent of women and 8.65 percent of men chose to litigate over pay discrimination, versus 26.09 percent of women and 30.30 percent of men would do so in the “slip and fall” case against the acquaintance. And, against the small corporation, 8.82 percent of women and 12.04 percent of men said they would sue for pay discrimination, whereas 8.11 percent and 12.38 percent would do so against their neighbor in the “slip and fall.”

These figures show that unless they are confronting a defendant whom they know very well, individuals—whatever their gender—are particularly disinclined to bring pay discrimination cases to court. This, in turn, means that the cases which become the subject of judicial policy making have been shaped by gender, albeit in a subtle way. It is not the gender of the plaintiff that impacts the decision to sue (though men's probability of starting litigation declined even more than women's) as much as it is whether the harm that plaintiff experience itself is gendered—in which case they are much less willing to file suit.

The reason for this is somewhat unclear. It may be that individuals believe they have a lower probability of success in discrimination cases and are therefore more reluctant to bring them to court. It could also be that those who experience discrimination do not consider these injuries “serious enough” to warrant formal legal action. Whereas most people recognize the type of physical harm included in the “slip and fall” vignette to be legitimate injury, the sense that one should not make a “big deal” over discrimination may be at play. Extant work indicates that economic and social pressures may lead women to take this approach with sexual harassment (see e.g., Reference HebertHebert 2007; Reference MarshallMarshall 2003). This study shows that this pattern may persist with pay discrimination as well, and, perhaps more notably, that both men and women are affected.

Neither men nor women are willing to just “lump it” (Reference MarshallMarshall 2005a: 10) in these types of cases, however. One of the advantages of the research design in this project is that it gave respondents several options for how to respond to a harm, not asking merely whether they would begin litigation or do nothing. As with the “slip and fall” injury, respondents actually were willing to take action over pay discrimination, but greatly preferred mediation or resolution outside the legal system. In other words, both genders refused to just accept discrimination. What they wanted were methods of conflict resolution that did not involve the formal procedures of a courtroom, trial, and jury.

That both men and women resist filing lawsuits about pay discrimination also stands in stark contrast to the frequency with which women's rights advocates and organizations have turned to courts over a range of “women's issues.” Regarding sexual harassment, pay and pregnancy discrimination in the workplace, sexual assault, reproductive rights, and family issues, reformers have long sought to address and remedy inequality through the legal system (see generally Reference Bartlett, Deborah and GrossmanBartlett et al. 2013; Reference LindgrenLindgren et al. 2011). This study does not undermine the importance of these efforts, but it does suggest that these cases are extraordinary, in terms of both the substantive legal claim and the plaintiffs willing to take legal action. When it comes to the discrimination experienced by ordinary individuals in their daily lives, courts are simply not a popular forum for resolution of the problem.

A similar disparity between the legal strategies (or lack thereof) of individuals and those of reformers could also exist among other disempowered groups, such as LGBT individuals and racial minorities. These equity advocates have often employed litigation to try and achieve political and social reform (Reference AndersonAnderson 2008; Reference KlarmanKlarman 2004, Reference Klarman2012; Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008). As with women, however, there has yet to be much study into whether individuals who confront discrimination based on race or sexual orientation pursue their own legal remedies (but see Reference GreeneGreene 2016). If future research indicates they do not, then there could multiple arenas in which elite reformers open the door for conflict resolution and remedying of inequality via courts and law, but private individuals rarely partake of the opportunity.

When it comes to the impact of the plaintiff's gender, the results were less robust than expected, but still give some indication it is affecting the legal decision making of individuals. In general, men and women's propensity to sue did not differ. However, while women are usually no less likely to opt for litigation than men are, they do sometimes favor the more cooperative and collaborative methods of dispute resolution (mediation) rather than opt for the zero-sum, “winner take all” approach of litigation to trial. The effect, however, exists only in certain types of cases and at certain stages of the legal process.

The findings suggest that women do not shy away from formalized conflict, but once that conflict has begun, they appear to want to resolve it in a way that is more likely to preserve the connection and harmony of the relationship. The study thus provides empirical evidence for the (usually) theoretical claims that women prefer to resolve conflict in a more conciliatory manner than their male counterparts. It also suggests that although women are not disproportionally affecting the sheer number of lawsuits in the legal system, they are affecting how these suits are resolved and may, by seeking alternative means of conflict resolution, be responsible for keeping a significant number of already-filed cases out the hands of a jury or judge.

This result has implications for the growing body of literature on conflict resolution. Scholars have noted the increasing prevalence of mediation in particular (Reference CalkinsCalkins 2008), and several have focused on its use in sexual harassment or gender discrimination cases (Hippensteele 2006; Reference Morgan and Paludi'sMorgan 2015; Reference OserOser 2004). This turn to mediation can be beneficial for women (Jarrett 2010; Reference Menkel-MeadowMenkel-Meadow 1998). Unlike litigation, which can reduce a female plaintiff's control over her case, provoke retaliatory legal action by the accused, and increase her sense of disempowerment (Reference Berrey, Hoffman and NielsenBerrey et al. 2012; Reference Morgan and Paludi'sMorgan 2015; Reference StambaughStambaugh 1997), mediation can serve a broad range of a female plaintiff's interests (beyond just financial compensation) and increase her feelings of empowerment (Reference Menkel-MeadowMenkel-Meadow 1998). Reference JarrettJarrett (2010) also suggests that, if it is properly structured and run by trained experts, mediation can remedy the “organizational structure and culture” that may have contributed to the harassment and reduce incidences of the behavior within the workplace and society writ large.

At the same time, mediation may further victimize women. Power imbalances exist when women challenge their (usually) male opponents, are forced to use potentially gender-biased and pro-defendant mediators, and are subject to the employer's interests in organizational “harmony” over justice for the employee-victim (Reference Berrey, Nelson and NielsenBerrey et al. 2017; Reference HippensteeleHippensteele 2006; Reference OserOser 2004; see also Reference GrilloGrillo 1991). By removing the case from the public arena of the courtroom, mediation also ensures that that gender discrimination remains private and the perpetrator escapes the public attention and shame that might inhibit future discriminatory behavior (Hippensteele 2006). Mediation also requires participants to have sophisticated knowledge of the procedure and to be able to assess, given “extralegal considerations” such as economic and family consideration, whether it serves their interests (Reference Morgan and Paludi'sMorgan 2015: 274; Reference Ver SteeghVer Steegh 2003). If, as this study indicates, women do prefer mediation, both they and their advocates should be aware of the risks involved and ensure that the female plaintiff is a fully informed participant.

In contrast to the study's findings about mediation, women were actually less willing than men to settle cases of pay discrimination. When women experience a physical injury, they seem to be as adversarial as men. But when they confront pay disparity, they appear to respond in a more adversarial manner by refusing the offer. This pattern persists even as they become more familiar with the defendant; indeed, the better the know the defendant, the less likely they were to settle. It seems from this finding that, just as in the political arena, when employment discrimination is involved, females are more active and assertive than men. When combined with their apparent preference to mediate, it appears therefore that women are amenable to resolving a dispute through communication and negotiation. What they are not willing to do is simply accept the opponent's proposed solution.

When it comes to relational distance, the study revealed little interaction with gender. In fact, both men and women are generally unaffected in any meaningful way by the extent of their relationship with the potential defendant. This result stands in contrast to both my expectations and that of some extant literature. Reference MorganMorgan (1999), for example, finds that intimate relationships (which she defines as spouse, children, and parents) shape women's decisions about whether to pursue claims of sexual harassment. Implicit in her work is an assumption that gender differences exist, such that men would not be similarly affected. The present study highlights both the need to consider non-intimate relationships (such as acquaintances, friends, and neighbors), and that some types of connections may not be influential on either genders’ decisions about legal strategy.

As with all studies, this one has limitations. Surveys are necessarily artificial and respondents may make much different choices in the “real world” than they might in response to a questionnaire of hypotheticals (Reference Berrey, Hoffman and NielsenBerrey et al. 2012). Unfortunately, gathering empirical data on cases that could have been filed but were not is quite challenging. A survey such as this may be the best way to assess if and how litigation proceeds as it does.Footnote 19 In addition, although there is much overlap between the construction of the relevant independent variable (relational distance) and its operationalization in the vignettes, a manipulation check could have improved the validity of the results. Last, it is worth noting that varying the size of the company in the pay discrimination vignettes may have led respondents to consider the financial resources of—rather than their lack of connection to—the potential defendant. Future surveys should clarify this distinction.

There are also multiple other avenues that warrant attention. As currently structured, the research design does not fully account for distinctions that may exist between the decision to sue a private individual (or groups of individuals) versus a corporation or other type of formal organization. A corporation was used in the vignettes here to align factually with the pay discrimination example, but future work could ensure consistency in the category of potential defendant across multiple types of legal issues.

When it comes to how gender affects the legal decision making of men and women, the gender of the defendant or the gender of the attorney also may play a role. In addition, work should expand to other “women's issues” to see if they also are less likely to end up in court or are mediated more by women than men. There may be particularly interesting patterns when comparing the legal decision making across different types women's issues where the defendant might be a former spouse (such as in a divorce or child custody case) or where the party responsible for the harm (the sexual harasser, for example) is not the legally actionable defendant (the employer). Reproductive rights claims generally involve suits against the government, which could open another dynamic into how the nature of the defendant shapes plaintiffs’ choices.

Whether and how minorities employ the legal system was not a primary focus of this study, but several findings are worth noting. Minorities are less likely to settle cases involving physical injury and may be more likely to file a lawsuit in employment discrimination disputes. The literature generally suggests that minorities mistrust the legal system, but my results suggest that this mistrust does not necessarily translate into a blanket refusal to employ that system. Indeed, as in other recent work (Reference Nielsen, McElhattan and WeinbergNielsen et al. 2017), the findings indicate that minorities may be more legally aggressive than their white counterparts, particularly once they have begun litigation. More scholarship is needed to examine this behavior. Future work, for example, could unpack the concept of “minority” and compare the litigation choices of different minority groups. The patterns documented here may vary across racial categories and/or be driven by one minority group in particular.Footnote 20

The study has added to our understanding of how litigants, their gender, and their relationships might affect the legal process. We know the judicial system is shaped by the behavior, and potentially the gender, of many legal actors, including judges, juries, and attorneys. This study highlights that it is the choices of ordinary citizens that generate and formulate the cases on which these actors work. Because these “inputs” to the legal system necessarily shape its “outputs,” we must attend to litigant choices as well and determine what role gender might play in their decision making. Only then can we truly see whether and to what extent the law itself is gender-biased.