1. Introduction

Blends have long been a source of new lexical elements in English word formation. Classic examples of such elements include -burger in words like soyburger or oysterburger, -furter in words like turkeyfurter or chickenfurter and -scape in cloudscape or manscape. Among more recent examples are -zilla (bridezilla, momzilla), -cation (staycation, mancation) or -splain(ing) (mansplaining, whitesplaining). Some of these have been studied in greater or lesser detail, highlighting various researchers’ interests in the topic, such as regularities in blend formation, formal and semantic patterns of blends, or the emergence of new combining forms from lexical blends (see in particular Baldi & Dawar, Reference Baldi, Dawar, Booij, Lehmann and Mugdan2000; Frath, Reference Frath2005; Kemmer, Reference Kemmer, Cuyckens, Berg, Dirven and Panther2003; Lalić–Krstin, Reference Lalić–Krstin and Prćić2014; Lehrer, Reference Lehrer1998; Mattiello, Reference Mattiello2017a, Reference Mattiello2017b; Panić–Kavgić & Kavgić, Reference Panić–Kavgić and Kavgić2009).

Typically, these new lexical elements originate as splinters, i.e. that part of a source word that is retained in a blend, and are then later reused in the formation of other words as ready-made elements, undergoing the process of morphemization along the way. They are typically classified either as combining forms or secreted affixes in the morphological literature, depending on their form, function and meaning (see e.g. Fradin, Reference Fradin, Doleschal and Thornton2000; Lehrer, Reference Lehrer and Munat2007; Mattiello, Reference Mattiello2017a; Prćić, Reference Prćić2007, Reference Prćić2008; Warren, Reference Warren, Dressler, Luschützky, Pfeiffer and Rennison1990). Another characteristic that these splinters have in common is that they sometimes proliferate whole series of analogically formed neologisms in English, often within a very short time span and frequently triggered by an important event (for example Brexit, see Lalić–Krstin & Silaški, Reference Lalić–Krstin and Silaški2018). According to Mattiello (Reference Mattiello2017a, Reference Mattiello2017b), in cases like these, analogy works in one of two ways, either as surface analogy or as analogy via schema. Surface analogy is defined as ‘the word-formation process whereby a new word [ . . . ] is coined that is clearly modelled on a precise actual model word. In surface analogy, the target can be associated with the model as far as it shares with it similarity in some (or more) trait(s)’ (Mattiello, Reference Mattiello2017a: 9). In contrast, analogy via schema occurs when a word is formed ‘after a set of concrete prototype words which share the same formation (i.e. series) or some of their bases/stems’ (Mattiello, Reference Mattiello2017a: 12). Although most of the neologisms coined in this way are not established in the lexicon and probably never will be, they are important because they illustrate a creative mechanism in the formation of new words.

In this paper, we explore a relatively new component, -nomics, evidenced in formations such as tweetonomics, shenomics, parentonomics and Bidenomics, in which this component originates from economics as a source word (Fischer & Wochele, Reference Fischer, Wochele, Kurras and Rizza2018; Mattiello, Reference Mattiello2019). Our aim is to discuss some aspects of the formation of -nomics coinages, classify the possible meanings of -nomics in such new coinages, illustrate these meanings with relevant examples, as well as to describe the process of analogy that these forms seem to have undergone. We hypothesize that the analysis of the -nomics component will result in a diversified semantic network of senses. The paper is structured in the following way. After this short introduction, in Section 2 we describe the materials and method used for the analysis. This is followed in Section 3 by an account of the meanings of the -nomics combining form established by the analysis, while in Section 4 we discuss the functioning of analogical patterns used in the formation of these words, as well as some of their semantic and formal features. Finally, we offer some concluding remarks.

2. Materials and method

The material was collected by querying the iWeb Corpus (Davies, Reference Davies2018) and the NOW Corpus (Davies, Reference Davies2016–) for the *nomics string. The iWeb Corpus contains 14 billion words from 22 million web pages and is among the largest available corpora of this kind. Although the large size of a corpus is not always a necessary prerequisite, it was convenient since our goal was to record as many words that contain -nomics as possible, even those that may not be very frequent. However, iWeb is a static corpus and no new texts have been added to it after its release in 2018. Therefore, in order to supplement our data with new instances of -nomics, especially those coined from 2020 onward, we also queried the NOW Corpus (Davies, Reference Davies2016–). The NOW Corpus contains newspaper and magazine texts from 2010 to the present time. It is also a monitor corpus, i.e. new texts are added on a regular basis, at a rate of about 180–200 million words of data each month (Davies, Reference Davies2016–), or around 2 billion words every year. At the time of our query (1 April 2021), it contained 12.3 billion words and had been updated the day before.

The query of the *nomics string in iWeb returned 1,344 hits and in |NOW 1,536 hits. After the duplicates had been removed, the list was further refined by eliminating (a) all the hits that contained economics (e.g. socioeconomics, macroeconomics), as this was not the object of our study, (b) those that happened to contain a homographic string (e.g. economics, genomics, ergonomics), and (c) those that contained obvious spelling/typing mistakes. All alternative spellings, which arise due to the unestablished nature of these lexemes, manifested especially in terms of capitalization and the use of the hyphen, were treated as variants of one word, e.g. TRUMP-ONOMICS, Trump-onomics, trump-onomics, TRUMP-O-NOMICS, Trump-o-nomics and trump-o-nomics were treated as one word. All the words that were obtained from searching the corpora were included, regardless of any associative meanings they may have, such as different levels of formality or dialectal or other variational differences. The final number of words analysed was 780. Table 1 and 2 contain the 50 most frequent words with the -nomics combining form in the iWeb and NOW corpora.

Table 1: The 50 most frequent words with –nomics (iWeb) (queried on 13 June 2019)

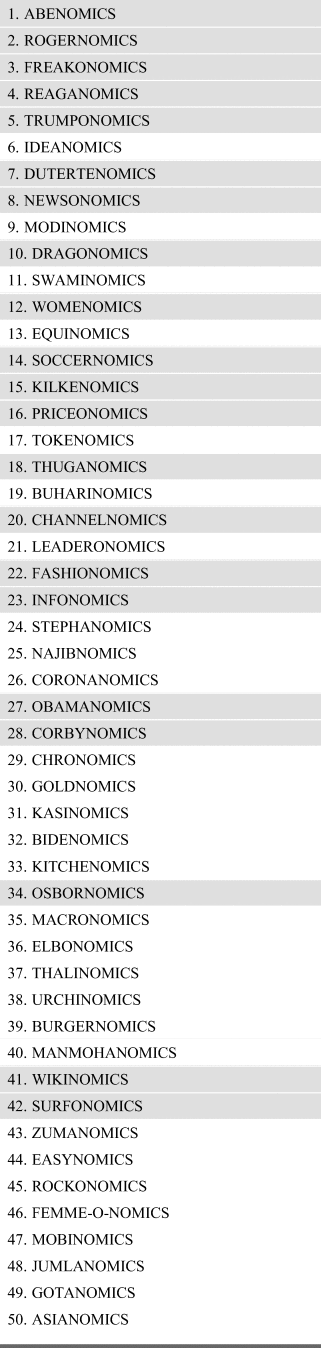

Table 2: The 50 most frequent words with –nomics (NOW) (queried on 1 April 2021)

A total of 21 -nomics words, which are shaded in grey in both tables, indicate the overlap between the two corpora. These are, in alphabetical order: Abenomics, Channelnomics, Corbynomics, Dragonomics, Dutertenomics, fashionomics, Freakonomics, infonomics, Kilkenomics, newsonomics, Obamanomics, Osbornomics, Priceonomics, Reaganomics, Rogernomics, soccernomics, surfonomics, Thuganomics, Trumponomics, Wikinomics, and womenomics.

3. Meanings of -nomics

Although the meaning of -nomics derived from economics as ‘the study of the way that goods and services are produced and sold and the way money is managed’ (Macmillan Dictionary, 2020) is detected in many of the examples in the corpora, the analysis will show that this combining form has also extended its meaning, giving rise to additional senses. Of the 780 words that we analysed, only a small number could be found in dictionaries and other reference books. Some were explained in the texts in which they were used and for some the meaning was elicited from the context. After establishing the meanings of the words, they were classified into the following groups discussed below.

3.1. Someone's economic policies

The first group comprises words where the identified meaning is ‘someone's economic policy’. It includes those in which the meaning of -nomics is ‘the economics of X’, or, more specifically, ‘principles of the economic policy of X’ (Fischer & Wochele, Reference Fischer, Wochele, Kurras and Rizza2018: 203), where X stands for the proper name of a politician advocating specific economic principles/policies, the name of a company whose operations are based on specific economic principles and policies, or alternatively, any person who shares their views about the economy. These eponymous formations, i.e. the structures of the type <proper name> + -nomics, started in specialized discourses, more precisely in economic political communication (Fischer & Wochele, Reference Fischer, Wochele, Kurras and Rizza2018) with Nixonomics (in late 1969), which then served as a model for other new coinages.

The overarching meaning of the -nomics creations – ‘someone's economic policy’ – can be divided into the following three sub-groups: (1) a politician's economic policies, (2) a company's way of doing business and (3) a personal view of economic issues.

3.1.1. A politician's economic policies

The words in this sub-group convey the meaning ‘a politician's economic policy’, which can be further paraphrased as ‘a set of varied economic ideas and measures a politician promotes’. These usually refer to presidents (e.g. Reaganomics, Dutertenomics, Clintonomics, Trumponomics, Bidenomics), prime ministers (Abenomics, Berlusconomics, Orbanomics) or opposition leaders (Corbynomics, Bernienomics). This meaning can at times be defined as ‘the course of economic policy modelled upon a politician's economic ideas’, in which case it becomes emotionally and ideologically charged, resulting in an additional shade of the original meaning, that of ‘a politician's economic policies which are considered to be bad for society’. Thus, Putinomics, Erdoganomics, Mugabenomics, Hugonomics, to mention some of the most notable examples, carry pejorative connotations.

3.1.2. A company's way of doing business

By analogy with the previous sub-group, the general meaning of ‘someone's economic policy’ is made specific in ‘a company's distinctive way of doing business’, which may be illustrated by Applenomics, Googlenomics, Goldman–Sachonomics, Teslanomics, Bezonomics, Muskonomics, in which the left-hand part includes either the name of the company or the name of the founder. As in the previous sub-group, the meaning of certain coinages may have an additional semantic aspect, that of a negative business practice. If it refers to an accounting fraud, such a way of doing business is labelled Enronomics.

3.1.3. Personal view of economic issues

The third sub-group comprises words denoting personal views of economic and financial issues and policies, as proposed and advocated by business analysts, experts, journalists and even lay people. Formations with -nomics are becoming increasingly widespread as brand names of blogs, podcasts, web platforms, Twitter hashtags, etc., where the authors are aiming to popularize economic topics, provide individualized solutions to the economic and financial problems of the day and make them accessible to the general public. The left-hand component of the coinage should suggest the part of the name/surname of the blogs’ authors and their views on, for example, job hunting (Brashenomics, after Ben Brashen), investment strategies (Pentonomics, after Michael Pento), or financial independence (Steveonomics, after Steve Reed).

This sub-group also gathers together examples where the personal views and the specific understanding of economic issues can be taken as a model. Examples include Wengernomics (after Arsene Wenger, the former manager of Arsenal), and Glazernomics (after the Glazer family, the owner of Manchester United), denoting these people's different views on managing a football club's revenues.

3.2. A study of something from the economic point of view

The meaning of -nomics in this group is related to numerous aspects, activities and segments of people's lives which may be tackled from the economic perspective. Examples include the economic aspects of the making and management of digital money (cryptonomics, blockchainonomics, bitcoinomics, tokenomics), climate (carbonomics), poverty (povertynomics), sports and games (soccernomics, fightnomics, yoganomics, pokernomics, wrestlenomics), digital news media (newsonomics), customer loyalty (likeonomics, perkonomics, retentionomics), job creation (jobenomics), film (popcornomics) and, specifically, the adult film industry (porn-o-nomics), providing good education to children (kidonomics), combatting the ageing process (juvenomics) or dating (lovenomics, dateonomics) and personal relationships (spousonomics). The -nomics combining form here most often refers to the calculation and assessment of the cost of engaging in a particular activity, often corroborated by elaborate statistical data. However, it can also refer to the costs and benefits of an activity, where examples include petonomics, ubernomics and momonomics (the costs and benefits of owning a pet, being an Uber driver and stay-at-home motherhood, respectively).

3.3. Providing economic/financial advice

Yet another, quite prolific, group of words found in the corpora is characterized by a shared meaning of -nomics: offering tips on how to manage or improve one's personal financial situation or, alternatively, defining a set of measures and policies for protecting a country's economy from the impact of adverse events.

3.3.1. Advice on how to secure public or personal finances in times of crises

The -nomics combining form in this sub-group refers to situations when an urgent need arises to help people secure their personal or family finances, retirement savings and even homes during times of financial turmoil or unexpected impoverishment, most often caused by a crisis, e.g. euronomics, Greekonomics, bubblenomics, crunchonomics, collapsonomics, flexenomics, etc. The current public health crisis caused by the COVID–19 pandemic has so far engendered covidnomics, coronanomics, coronavirunomics, pandemanomics, pandenomics, lockdownomics, all relating to the challenges imposed by the pandemic on a country's economy and the global economy, as well as how to continue functioning while at the same time containing the virus. A similar meaning of -nomics in these particular coinages may also refer to the consequences of the pandemic on individuals and how to survive the COVID–19 crisis financially.

3.3.2. Advice on how to make or save money

A number of the -nomics words in the corpora have to do with money-making ideas and income-boosting advice. Some examples include inkonomics (making money as a tattoo artist), apponomics (how app developers can make money with their apps), equinomics (making money with a horse business), etc.

This sub-group of the -nomics coinages also encompasses those where the focus is on economizing and living on a tight budget, e.g. barkonomics (saving money on dog care), babynomics (how parents can save money while raising a child), bangernomics (saving money by buying and running an old car), divanomics (how to be beautiful even if you are broke), brokenomics (how to live the good life without spending a ton of money), etc.

3.4. Names of companies

Companies’ names worldwide are increasingly becoming more creative and having –nomics in them seems to be very fashionable nowadays; it seems to be serving an important purpose of drawing attention to a business. In some examples, the left-hand component suggests the business sector of the company: selling quality women's fashion (Fashionomics), technology and communications (Telenomics and Telconomics, respectively), developing epigenetics solutions (Epinomics), providing technology solutions to web and cloud platforms (Webnomics), etc.

3.5. Book titles and names of videogames, organized events, conferences etc.

Similar to companies’ names, the -nomics combining form further demonstrates its productivity in book titles (the best-selling book Freakonomics; Likeonomics, on likeability as a secret to making more money; Wikinomics, on the use of mass collaboration for business success), videogames (Dobbernomics, where hockey meets economics, or Virtonomics, a business simulation game), as well as names of organized events, festivals, conventions and even scientific conferences (cf. Lalić–Krstin, Reference Lalić–Krstin and Prćić2014: 270 for -geddon), etc. In a number of the latter examples, the left-hand component of the coinage specifies the particular type of event, e.g. Pressnomics (related to the use of the website creation platform WordPress in business), Searchnomics (on search engine marketing), Prosecconomics (referring to the Italian wine sector), Lawyernomics (on legal marketing and technology), Startonomics (related to start-ups and digital technologies), etc.

4. Discussion

The above examples suggest that there is a clear analogical pattern used in the formation of the -nomics words. Unlike non-analogical coinages, which are formed by the application of word-formation rules without a particular concrete word that served as a model for their formation, analogical coinages are either ‘based on a precise actual model word’ or ‘a set of concrete prototype words which share the same formation (i.e. series) or some of their bases/stems (i.e. word family)’ (Mattiello, Reference Mattiello2017a: 12).

Our data reveals that both of these mechanisms have contributed to the creation of the -nomics coinages. The combining form -nomics started as a splinter, probably in the late 1960s and early 1970s, in Nixonomics, followed by McGovernomics and then in the 1980s by Reaganomics, Miterranomics and others, all following the initial model. They share both formal and semantic traits with the model in that they are all formed by combining the name of a politician (unabbreviated) and -nomics (including even the overlapping n) and they all have the semantic structure of ‘the economic policy of X’. After that came not only Clintonomics and Obamanomics but also many other new coinages, with different formal makeups and semantic generalizations and specializations, giving rise to a word-formation schema. A particular trigger for the proliferation of other coinages seems to have been Freakonomics, the title of a best-selling book by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner, published in 2005.

From the point of view of formation patterns, the new words no longer follow the sole model of ‘proper name’ + -nomics but are also formed with other types of initial elements, both in terms of function and meaning, as can be seen in Section 3. In that respect, the pool of potential source words has expanded to include common nouns (e.g. imagenomics, parcelnomics, pizzanomics), pronouns (e.g. shenomics), verbs (e.g. listenomics, likeonomics, barkonomics) and adjectives (e.g. brokenomics, chiconomics), attesting to the high productivity of -nomics in the coinage of new words. Also, there seems to be a preference for the initial source word to remain whole although truncated bases have also been found (e.g. Inomics, Preponomics, Herconomics), a tendency which has been reported in some corpus-based studies on similar word-formational elements (Lalić–Krstin, Reference Lalić–Krstin and Prćić2014; Rúa, Reference Rúa, Renner, Maniez and Arnaud2012).

Regarding the meaning, there is evidence of semantic generalization. From the original meaning of economics as ‘the study of the way that goods and services are produced and sold and the way money is managed’ there is a metonymical transfer to ‘someone's economic policy’, where that someone was initially a politician, but then extended to ‘company’ and ‘person’. A further extension is to ‘someone's view of economic policy’ and then even more widely to ‘a study of something from the economic point of view’. The use of this combining form in names of businesses, conferences and other events is a marketing strategy that relies on novelty and structural transgression as attention-grabbing devices, whereas its use in less technical registers reflects the popularization of and increasing interest in economics among lay audiences. However, the analysis has revealed that, contrary to our hypothesis stating that the highly productive character of -nomics will result in a diversified semantic network of meanings, this combining form has developed polysemy through different coinages, where the categories identified are to a higher or lesser degree variations of the original meaning of -nomics. Still, it seems that due to its productivity, popularity and easy recognizability of its possible meanings, the -nomics combining form encourages English speakers to create new coinages (cf. Mattiello, Reference Mattiello2019: 24) (as attested by the most recent examples such as covidnomics, lockdownomics, coronavirunomics, pandenomics, etc.).

5. Conclusion

The main aim of the present study has been to provide an overview of the established meanings of the -nomics combining form. The analysis of our material has demonstrated that -nomics is very productive, shown not only by the number of coinages it creates but more importantly by being used in contexts which go beyond those closely linked to economics or politics, in which it first originated; this is attested by the variety of aspects, activities and segments of people's lives to which these coinages may refer. This may serve as an indicator that the newly coined English words containing -nomics are created regularly by speakers, who appear to use this form ‘quite naturally expecting other language users to recognize and understand their coinages’ (Jurado, Reference Jurado2019: 22). It remains to be seen in future research to what extent the pervasiveness of -nomics coinages will be accompanied by more specific meanings of this combining form. What can be ascertained even now is that they do not seem to be a transient linguistic fad triggered by a specific event (cf. Lalić–Krstin, Reference Lalić–Krstin and Prćić2014: 271) but that the -nomics combining form may prove to be a more lasting addition to the English lexicon.

Acknowledgement

The second author acknowledges funding received by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia.

GORDANA LALIĆ–KRSTIN is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad, Serbia. Her research interests lie in the fields of lexicology, lexicography, cognitive linguistics and, more specifically, neologisms and lexical blends. Email: [email protected]

GORDANA LALIĆ–KRSTIN is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad, Serbia. Her research interests lie in the fields of lexicology, lexicography, cognitive linguistics and, more specifically, neologisms and lexical blends. Email: [email protected]

NADEŽDA SILAŠKI is Professor of English at the Faculty of Economics, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her research interests include metaphor studies, critical discourse analysis and economics discourse. She has published in Discourse, Context & Media, English Today, Metaphor and the Social World, Journal of Language and Politics, and Ibérica. She is currently editor-in-chief of ESP Today – Journal of English for Specific Purposes at Tertiary Level. Email: [email protected]

NADEŽDA SILAŠKI is Professor of English at the Faculty of Economics, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her research interests include metaphor studies, critical discourse analysis and economics discourse. She has published in Discourse, Context & Media, English Today, Metaphor and the Social World, Journal of Language and Politics, and Ibérica. She is currently editor-in-chief of ESP Today – Journal of English for Specific Purposes at Tertiary Level. Email: [email protected]

TATJANA ĐUROVIĆ is Professor of English at the Faculty of Economics, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her research interests lie in cognitive linguistics, critical discourse analysis and English for specific purposes. She has published widely in international peer-reviewed journals and contributed chapters to edited books published by John Benjamins and Bloomsbury. She is currently associate editor of ESP Today – Journal of English for Specific Purposes at Tertiary Level. Email: [email protected]

TATJANA ĐUROVIĆ is Professor of English at the Faculty of Economics, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her research interests lie in cognitive linguistics, critical discourse analysis and English for specific purposes. She has published widely in international peer-reviewed journals and contributed chapters to edited books published by John Benjamins and Bloomsbury. She is currently associate editor of ESP Today – Journal of English for Specific Purposes at Tertiary Level. Email: [email protected]