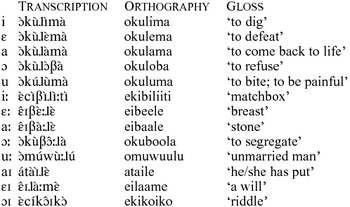

Lusoga is an interlacustrine Bantu language spoken in the eastern part of Uganda in the region of Busoga, which is surrounded by the Victoria Nile in the west, Lake Kyoga in the north, the River Mpologoma in the east and Lake Victoria in the south. According to the 2002 census, this language is spoken by slightly over two million people (UBOS 2006: 12).

There are four main language varieties spoken in Busoga: Lusoga (also known as Lutenga), Lulamoogi, Lusiginhi and Lower Lunyole. Preliminary findings from a recently concluded fieldwork study of the varieties spoken in Busoga show that Lulamoogi and Lusiginhi border the Nilotic languages of Lango and Adhola respectively and it is possible that the varieties grew out of this relationship. Lower Lunyole, a variety bordered by Lusoga (Lutenga) and Lake Victoria in the south of Busoga, is the most distant of all. Although there is considerable argument for not considering Lunyole as part of Lusoga, it is worth noting that Lunyole is the language of one of the eleven chiefdoms that make up the royal houses of the Busoga kingdom. This house is headed by the clan chief known as Nanhumba, who hails from the Busoga county of Bunhole.

Lusoga has developed naturally as the region's lingua franca and it is the variety closest to Luganda: it is estimated that both languages have a lexical similarity of between 82% and 86% (Lewis, Simons & Fennig Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2013). A considerable number of Lusoga texts have been produced both formally and informally, most notably by institutions like the Cultural Research Center (CRC; http://www.crcjinja.org/) and personalities like Cornelius Gulere (http://muele.academia.edu/CorneliusGulere), but the majority of these productions do not provide well-founded linguistic descriptions of Lusoga. These publications continue to base their description on the Luganda orthography because it was the official language of instruction in the region (Ladefoged, Glick & Criper Reference Ladefoged, Glick and Criper1972: 87–99). Lusoga only featured for the first time in the Ugandan language policy in 2005 (NCDC 2006: 5). Despite its role as a medium of instruction in primary education since 2005, Lusoga is still an oral language and remains largely undocumented (Nabirye & De Schryver Reference Nabirye and de Schryver2010: 327–328).

Although there had been some research on Lusoga early in this century (Yukawa Reference Yukawa2000, Steeman Reference Steeman2001, Van der Wal Reference Van der Wal2004), the interest in the language surged after its official recognition in 2005. Examples include an update of the Lusoga orthography, the first monolingual Lusoga dictionary and a number of scientific linguistic descriptions of Lusoga (Nabirye Reference Nabirye2008, Reference Nabirye2009a, Reference Nabiryeb, Reference Nabirye and Zhu2010; Namyalo et al. Reference Namyalo, Walusimbi, Bukenya, Masakala, Nabirye and Kiingi2008; De Schryver & Nabirye Reference De Schryver and Nabirye2010; Nabirye & De Schryver Reference Nabirye and de Schryver2011, Reference Nabirye and de Schryver2013). The description of the Lusoga sound system presented here is one of such efforts. It results from extensive fieldwork conducted in January 2012, when sound recordings were made in the 11 Busoga counties that make up Busoga; a total of 39 speakers were involved. However, the sound inventory presented here only represents the Lusoga variety spoken in Buwaabe (N 0o 36’ 05”, E 33o 39’ 49”) in Bugweri county, Iganga district. The recordings used in this illustration are those of a 40-year-old Lusoga speaker born in Buwaabe. At this stage it is too early to comment on any regional pronunciation differences between varieties.

Consonants

The consonant chart below lists the Lusoga sounds which have been found to provide phonological contrast. The sounds in parentheses have been attested in the language, but they are very rare. They have not been included in any of the numerical counts in this paper.

While the Upper Lunyole consonant system consists of 62 consonants (Namulemu Reference Namulemu2006), Lusoga has 70. The size of this consonant inventory is to be considered as large given that the mean consonant inventory size across the world's languages is 22.7 (Maddieson Reference Maddieson, Dryer and Haspelmath2011).

Lusoga has plosives at five places of articulation with a clear phonemic distinction between a dental and an alveolar place of articulation. This is evident from near-minimal pairs like [ὲbì

![]() ὲpὲɺὲ] ‘fried cookies’ vs. [ὲbítὲɺὲkὲ] ‘parcels’ and [

ὲpὲɺὲ] ‘fried cookies’ vs. [ὲbítὲɺὲkὲ] ‘parcels’ and [

![]() músàː

músàː

![]() à] man’ vs. [

à] man’ vs. [

![]() kùsàːdà] ‘to shake a liquid in a container’.

kùsàːdà] ‘to shake a liquid in a container’.

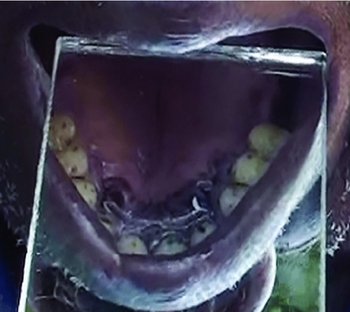

Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 20–23) suggest that dental plosives tend to be laminal with tongue contact on both the teeth and the anterior part of the alveolar ridge, while alveolar plosives tend to be apical with tongue tip contact in the middle of the alveolar ridge. The palatograms in Figures 1–6 show that this also appears to be the case in Lusoga.

Figure 1 Palatogram of the dental plosive in [a

![]() a]. The bulk of the occlusion is against the rear of the upper teeth.

a]. The bulk of the occlusion is against the rear of the upper teeth.

Figure 2 Palatogram of the alveolar plosive in [a t a] with well-defined contact on the alveolar ridge only.

Figure 3 Palatogram of the voiced dental plosive in [a

![]() a] showing tongue contact with the back of the upper teeth and the anterior portion of the alveolar ridge. Dental contact is asymmetrical in the midsagittal plane.

a] showing tongue contact with the back of the upper teeth and the anterior portion of the alveolar ridge. Dental contact is asymmetrical in the midsagittal plane.

Figure 4 Palatogram of the voiced alveolar plosive in [a d a] with contact on the alveolar ridge only.

Figure 5 Palatogram of the dental nasal in [a

![]() a] showing tongue contact with the back of the upper teeth and the anterior portion of the alveolar ridge.

a] showing tongue contact with the back of the upper teeth and the anterior portion of the alveolar ridge.

Figure 6 Palatogram of the alveolar nasal in [a n a] with contact on the alveolar ridge only.

At all places of articulation, the plosive pairs are distinguished in terms of voicing. This is witnessed by (near-)minimal pairs like [

![]() kùpìkà] ‘to put pressure into something’ vs. [

kùpìkà] ‘to put pressure into something’ vs. [

![]() kúbìkà] ‘to relay bad news’; [ὲbì

kúbìkà] ‘to relay bad news’; [ὲbì

![]() ὲpὲɺὲ] ‘fried cookies’ vs. [ὲbì

ὲpὲɺὲ] ‘fried cookies’ vs. [ὲbì

![]() ὲɡὲɺὲ] ‘chains’; [

ὲɡὲɺὲ] ‘chains’; [

![]() kútàɺà] ‘to get ready to fight’ vs. [

kútàɺà] ‘to get ready to fight’ vs. [

![]() kúdàɺà] ‘to be jolly’; [

kúdàɺà] ‘to be jolly’; [

![]() kùcá] ‘to stop; to become day’ vs. [

kùcá] ‘to stop; to become day’ vs. [

![]() kùɟá] ‘to go’; [

kùɟá] ‘to go’; [

![]() kùkàːwà] ‘to be sour’ vs. [

kùkàːwà] ‘to be sour’ vs. [

![]() kùɡàːwà] ‘to go bad (of food)’.

kùɡàːwà] ‘to go bad (of food)’.

Voiceless plosives have a short Voice Onset Time (< 30 msec in the recordings provided with this illustration), while the voiced plosives have considerable prevoicing. The palatal plosives [c] and [ɟ] are typically realized as affricates [tʃ] and [dʒ]: [càːβàzíːŋɡà] (title of the Busoga king) and [

![]() kùɟá] ‘to go’. The glottal stop only occurs as the strong onset of word-initial vowels: [ʔí

kùɟá] ‘to go’. The glottal stop only occurs as the strong onset of word-initial vowels: [ʔí

![]() àífὲ] ‘queen of Busoga’. The occurrence of a glottal stop often gives rise to a significant creaky voice quality on the preceding and following vowels especially in the context of low tones.

àífὲ] ‘queen of Busoga’. The occurrence of a glottal stop often gives rise to a significant creaky voice quality on the preceding and following vowels especially in the context of low tones.

The labial, dental, alveolar and velar plosives also occur with labialization and these contrast with the plain plosives: there are clear minimal pairs for [b], e.g. [ὲːm

b

wá] ‘dog’ vs. [ὲːm

bá] ‘jaws’, [t], e.g. [

![]() kùt

wâːɺà] ‘to take’ vs. [

kùt

wâːɺà] ‘to take’ vs. [

![]() kútàɺà] ‘to get ready to fight’, [d], e.g. [

kútàɺà] ‘to get ready to fight’, [d], e.g. [

![]() ːn

d

wáíɺέ] ‘diseases’ vs. [ὲːn

dà] ‘stomach/pregnancy’, [k], e.g. [

ːn

d

wáíɺέ] ‘diseases’ vs. [ὲːn

dà] ‘stomach/pregnancy’, [k], e.g. [

![]() kùk

wàːjà] ‘to make noise (of paper, leaves, plastic)’ vs. [

kùk

wàːjà] ‘to make noise (of paper, leaves, plastic)’ vs. [

![]() kùkàːjà] ‘to make bitter’ and [ɡ], e.g. [

kùkàːjà] ‘to make bitter’ and [ɡ], e.g. [

![]() mùɡwâːɡwá] ‘stupid person’ vs. [

mùɡwâːɡwá] ‘stupid person’ vs. [

![]() múɡáːɡà] ‘type of tree’. There is no minimal pair for [p], [

múɡáːɡà] ‘type of tree’. There is no minimal pair for [p], [

![]() ] and [

] and [

![]() ] but there is evidence that they have labialized counterparts in similar phonetic environments, e.g. [p

wìːp

wìːp

wì] ‘very early morning’ vs. [

] but there is evidence that they have labialized counterparts in similar phonetic environments, e.g. [p

wìːp

wìːp

wì] ‘very early morning’ vs. [

![]() kùpìkà] ‘to put pressure into something’ and [

kùpìkà] ‘to put pressure into something’ and [

![]() βù

βù

![]() wá] ‘intelligence’ vs. [

wá] ‘intelligence’ vs. [

![]() βú

βú

![]() àmà] ‘dirtiness’. Furthermore, the voiceless and voiced alveolar plosives occur in phonemic contrast with the palatalized alveolar plosive, e.g. [

àmà] ‘dirtiness’. Furthermore, the voiceless and voiced alveolar plosives occur in phonemic contrast with the palatalized alveolar plosive, e.g. [

![]() kùt

já] ‘to fear’ vs. [

kùt

já] ‘to fear’ vs. [

![]() kùtá] ‘to put’ and [

kùtá] ‘to put’ and [

![]() kúɡùd

jà] ‘to bite severely’ vs. [

kúɡùd

jà] ‘to bite severely’ vs. [

![]() kùɡùdà] ‘to gulp’.

kùɡùdà] ‘to gulp’.

Lusoga has 20 prenasalized plosives. Prenasalized consonants in this paper have been considered as unitary segments for at least the following six reasons: (i) the overall duration of these sounds falls well within the range of what can be expected for a single sound; (ii) the prenasalizations are always homorganic, so their phonetic realization is dependent on the place of articulation of the plosive; (iii) if syllables are taken to start with a cluster consisting of two segments, the sonority hierarchy predicts that the segment with the lowest sonority (i.e. the plosive) occurs first; (iv) Lusoga has minimal pairs contrasting prenasalized plosives with plain ones, e.g. [

![]() kúɡûːm

bà] ‘to gather; to grow’ vs. [

kúɡûːm

bà] ‘to gather; to grow’ vs. [

![]() kùɡùbà] ‘to become dirty’, [

kùɡùbà] ‘to become dirty’, [

![]() mùpûːn

tà] ‘surveyor’ vs. [

mùpûːn

tà] ‘surveyor’ vs. [

![]() mùtápùtà] ‘interpretor’, [

mùtápùtà] ‘interpretor’, [

![]() kúwàːn

dà] ‘to spit’ vs. [

kúwàːn

dà] ‘to spit’ vs. [

![]() kùwàdà] ‘to accuse falsely; try’, [

kùwàdà] ‘to accuse falsely; try’, [

![]() ːŋ

kàtà] ‘head cushion’ vs. [kàtá] ‘almost’, and [

ːŋ

kàtà] ‘head cushion’ vs. [kàtá] ‘almost’, and [

![]() kúsíːŋɡà] ‘to win’ vs. [

kúsíːŋɡà] ‘to win’ vs. [

![]() kúsìɡà] ‘to sow’; (v) Lusoga has minimal pairs contrasting prenasalized consonants with full nasal phonemes, e.g. [

kúsìɡà] ‘to sow’; (v) Lusoga has minimal pairs contrasting prenasalized consonants with full nasal phonemes, e.g. [

![]() kǔːm

pà] ‘to give me’ vs. [

kǔːm

pà] ‘to give me’ vs. [

![]() kùmà] ‘you light a fire’; (vi) the prenasalized plosives participate in the same processes of labialization and palatalization as the plain plosives.

kùmà] ‘you light a fire’; (vi) the prenasalized plosives participate in the same processes of labialization and palatalization as the plain plosives.

A comparison with prenasalization of the plosives in the UPSID corpus (UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory Database; Maddieson Reference Maddieson1984) reveals that 53 of the 451 languages included in UPSID (11.75%) have prenasalized plosives. The total number of prenasalized plosives in Lusoga is exceptionally high in comparison to the UPSID mean (2.92).

Nasals occur at four places of articulation: labial, dental, alveolar and velar. The Lusoga variety does not have a palatal nasal which occurs in the other varieties. The labial, dental and alveolar nasals contrast with a labialized counterpart; there are minimal pairs for [m], e.g. [

![]() m

wíːzὲ] ‘return him/her’ vs. [

m

wíːzὲ] ‘return him/her’ vs. [

![]() mìzέ] ‘you have swallowed’, [

mìzέ] ‘you have swallowed’, [

![]() ], e.g. [ὲc

], e.g. [ὲc

![]() n

wá] ‘bundle of firewood’ vs. [ὲcí

n

wá] ‘bundle of firewood’ vs. [ὲcí

![]() à] ‘gecko lizard’ and [n], e.g. [ὲcìn

wá] ‘ugly mouth’ vs. [ὲcíːná] ‘hole’. Furthermore, the labial nasal occurs in opposition with a palatalized labial nasal, e.g. [

à] ‘gecko lizard’ and [n], e.g. [ὲcìn

wá] ‘ugly mouth’ vs. [ὲcíːná] ‘hole’. Furthermore, the labial nasal occurs in opposition with a palatalized labial nasal, e.g. [

![]() kútὲm

jà] ‘to blink’ vs. [

kútὲm

jà] ‘to blink’ vs. [

![]() kútὲmà] ‘to cut’.

kútὲmà] ‘to cut’.

Geminate nasals also occur and these typically surface as the result of Meinhof's Law (or the Ganda Law): ‘a nasal + voiced consonant sequence becomes a geminate nasal when the next syllable also begins with a nasal’ (Hyman Reference Hyman, Nurse and Philippson2003: 52). Nouns in classes 9 and 10 (which take the prefix eN-) are especially affected: e.g. eN-[βaːm

b

a] > emmamba [

![]() mːàːm

bà] ‘meat’, eN-[j

aːŋɡɛ]> ennhange [

mːàːm

bà] ‘meat’, eN-[j

aːŋɡɛ]> ennhange [

![]()

![]() ːàːŋɡὲ] ‘dove’, eN-[ɡɛːn

dɔ]> eŋŋendo [ὲŋː

ːàːŋɡὲ] ‘dove’, eN-[ɡɛːn

dɔ]> eŋŋendo [ὲŋː

![]() ːn

d

ːn

d

![]() ] ‘journeys’. Geminate nasals also surface with the first person singular morpheme (-N-), either as subject (e.g. N-[jɛːn

d

a] > nnhenda [

] ‘journeys’. Geminate nasals also surface with the first person singular morpheme (-N-), either as subject (e.g. N-[jɛːn

d

a] > nnhenda [

![]() ὲːn

dà] ‘I want’) or as object (e.g. [a]-N-[βiːŋɡ] [a] > amminga [àmːìːŋɡà] ‘he chases me’). Nasals are the only sounds in Lusoga which occur as singletons and geminates.

ὲːn

dà] ‘I want’) or as object (e.g. [a]-N-[βiːŋɡ] [a] > amminga [àmːìːŋɡà] ‘he chases me’). Nasals are the only sounds in Lusoga which occur as singletons and geminates.

Lusoga has no trills, but it has an alveolar lateral flap in words like: [ŋːwáɺí] ‘crested crane’, [

![]() múwùːɺù] ‘umarried man’, [ὲːm

p

wíɡùɺú] ‘owl’ and [

múwùːɺù] ‘umarried man’, [ὲːm

p

wíɡùɺú] ‘owl’ and [

![]() ɪβàːɺὲ] ‘stone’. The speaker who has read the words for this Illustration displayed significant variability in the pronunciation of the lateral flap. Sometimes it is realized as an alveolar tap as in [ὲcìβìɾìːtì] ‘matchbox’, [

ɪβàːɺὲ] ‘stone’. The speaker who has read the words for this Illustration displayed significant variability in the pronunciation of the lateral flap. Sometimes it is realized as an alveolar tap as in [ὲcìβìɾìːtì] ‘matchbox’, [

![]() ɪβὲːɾὲ] ‘breast’ and [

ɪβὲːɾὲ] ‘breast’ and [

![]() ːn

zìɾ

ːn

zìɾ

![]() ] ‘soot’. In other instances, it appears as an alveolar lateral approximant: [

] ‘soot’. In other instances, it appears as an alveolar lateral approximant: [

![]() ɪd

wâːlìl

ɪd

wâːlìl

![]() ] ‘hospital’, [

] ‘hospital’, [

![]() kùl

kùl

![]() βà] ‘to refuse’. Alveolar lateral flaps are rare in languages of the world: UPSID lists nine languages (2%) with this sound. One of the better-known examples is Japanese (Okada Reference Okada1991). In Lusoga, the alveolar lateral flap occurs contrastively with a labialized flap: [

βà] ‘to refuse’. Alveolar lateral flaps are rare in languages of the world: UPSID lists nine languages (2%) with this sound. One of the better-known examples is Japanese (Okada Reference Okada1991). In Lusoga, the alveolar lateral flap occurs contrastively with a labialized flap: [

![]() kùɺwà] ‘to be late’ vs. [

kùɺwà] ‘to be late’ vs. [

![]() kùɺà] ‘you grow up’, [ὲcíɡ

kùɺà] ‘you grow up’, [ὲcíɡ

![]() ːn

dὲɺὲɺwà] ‘aim, goal’ vs. [ὲcíɡ

ːn

dὲɺὲɺwà] ‘aim, goal’ vs. [ὲcíɡ

![]() ːn

dὲɺὲɺà] ‘is intended’. In addition, it contrasts with a palatalized flap, e.g. [

ːn

dὲɺὲɺà] ‘is intended’. In addition, it contrasts with a palatalized flap, e.g. [

![]() kùɺjá] ‘to eat’ vs. [

kùɺjá] ‘to eat’ vs. [

![]() kùɺà] ‘you grow up’, [

kùɺà] ‘you grow up’, [

![]() ɪɺjà] ‘marriage’ vs. [

ɪɺjà] ‘marriage’ vs. [

![]() ɪɺà] ‘later’.

ɪɺà] ‘later’.

Lusoga has fricatives at six places of articulation: the labio-dental and alveolar fricatives are represented by a voiceless and voiced member each, while the labial and velar places have a voiced fricative only. There is substantial variability in the phonetic realization of the velar fricative [ɣ], which may range from palatal/prevelar to outright uvular. Nevertheless, palatal and uvular realizations are not phonemic. The glottal fricative is very rare. The plain alveolar fricatives contrast phonemically with their labialized counterparts: [

![]() kùs

wáːɺá] ‘to be ashamed’ vs. [

kùs

wáːɺá] ‘to be ashamed’ vs. [

![]() kùsàːɺà] ‘to make a hissing sound’ and [àːn

z

wíːɺὲ] ‘he/she has found me’ vs. [

kùsàːɺà] ‘to make a hissing sound’ and [àːn

z

wíːɺὲ] ‘he/she has found me’ vs. [

![]() ːn

zìɺ

ːn

zìɺ

![]() ] ‘soot’. Very exceptionally, labialized labio-dental fricatives are heard, but they are not contrastive: [

] ‘soot’. Very exceptionally, labialized labio-dental fricatives are heard, but they are not contrastive: [

![]() kùf

wàːw

kùf

wàːw

![]() ] and [

] and [

![]() kùfàːw

kùfàːw

![]() ] ‘to become extinct’, [

] ‘to become extinct’, [

![]() kùv

wàːw

kùv

wàːw

![]() ] and [

] and [

![]() kùvàːw

kùvàːw

![]() ] ‘to leave’. The labial fricative contrasts with a palatalized labial fricative, e.g. [ὲβjâːn

dà] ‘long span of time’ vs. [ὲβàːn

dà] ‘it hits’.

] ‘to leave’. The labial fricative contrasts with a palatalized labial fricative, e.g. [ὲβjâːn

dà] ‘long span of time’ vs. [ὲβàːn

dà] ‘it hits’.

Lusoga also has five prenasalized fricatives which – just like the plosives – have been treated as unitary segments for reasons stated earlier. Two (near-)minimal pairs are: [

![]() m

w

m

w

![]() ːɱ

vù] ‘ripe’ vs. [

ːɱ

vù] ‘ripe’ vs. [

![]() m

wέːvù] ‘educated’ and [ὲːɱ

vú] ‘grey hair’ vs. [

m

wέːvù] ‘educated’ and [ὲːɱ

vú] ‘grey hair’ vs. [

![]() ɪvù] ‘ash’. Only seven UPSID languages (1.55%) have prenasalized fricatives.

ɪvù] ‘ash’. Only seven UPSID languages (1.55%) have prenasalized fricatives.

Lusoga has two approximants: [w] and [j].

A comparison of the Lusoga secondary articulations with languages in UPSID reveals that labialization occurs in 84 out of the 451 UPSID languages (18.63%). In this database, the number of labialized sounds varies between 0 and 29 with a mean of 4. Lusoga has 20 labialized sounds with a complete series of labialized stops and nasals, and an incomplete set in the fricatives. As far as palatalization is concerned, 35 of the UPSID languages (7.76%) have palatalized sounds with a mean of 5.2 and a range between 0 and 17. Lusoga has 13 palatalized sounds, none of which constitute a complete series.

Vowels

Lusoga has five qualitatively different vowels with a phonemic length distinction. With this system, it has the most frequent vowel system across the languages of the world. In addition, Lusoga has three rising diphthongs which are not the result of morphophonology. Although there are some examples of dipthongs in Lower Lunyole, their occurrence is rare when compared to the other Lusoga varieties.

Prosody

Preliminary research indicates that Lusoga has a reversive tone system. Bantu languages whose tone system falls in this category have inverted the tones of Proto-Bantu reconstructed forms, i.e. H is realised as L and vice versa (Marlo Reference Marlo2013). Lusoga has four tones: H, L, HL and LH. Some of the tones create lexical contrast, as illustrated in the examples below.

Transcriptions

English version

The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger, when a traveller came along wrapped in a warm cloak. They agreed that the one who first succeeded in making the traveller take his cloak off should be considered stronger than the other. Then the North Wind blew as hard as he could, but the more he blew the more closely did the traveller fold his cloak around him. And at last the North Wind gave up the attempt. Then the Sun shone out warmly, and immediately the traveller took off his cloak. And so the North Wind was obliged to confess that the Sun was the stronger of the two.

Orthographic version

Lunaku lulala, empewo dh’omu mambuka n’endhuba by’etaba mu kusindanwa okusobola okubona ani ku byombi asinga amaanhi. Byali bikaali awo, waidhawo omutabaazi eyali yeesuuliile ekigoye ekimusuuya. Bano abaali mu ntaka dh’okusindanwa baasalawo okwikilizigania nti, anaasooka okuleetela omutabaazi oyo okwewembula ekigoye kye yeewembeleile ni aidha okuba asinze mwine. Olwo, empewo dh’omu mambuka dhaatoolela dhaakunta n’amaanhi amabitilivu; aye ye dhaakoma okufuuwa, omutabaazi ye yakoma okwezingila ekigoye kye. Enkomelelo ya byonabyona yali ya mpewo dha mu mambuka kuva mu luyookaano. Olwo ni omusana gw’avaayo gwona gw’ayaka okwekansa. Amangu n’embilo, omutabaazi yeebwikula ekigoye kye yali yeewembeleile. Ekyavaamu, empewo dh’omu mambuka dhaalina okwemenha dhaikiliza nti, bwene omusana n’ogwali gudhisinga amaanhi.

Phonetic transcription

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Steven Batwala for participating in the palatography recording. Furthermore, we are grateful for several useful suggestions from two anonymous reviewers.