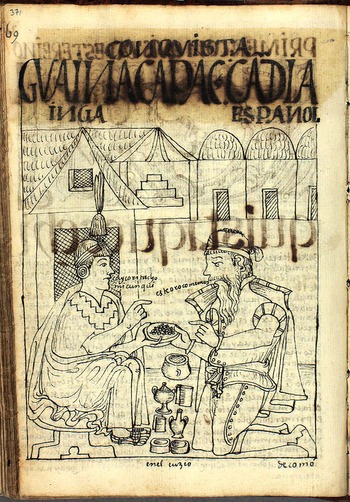

In his Primer nueva coronica y buen gobierno, the Amerindian chronicler Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala (1534–1615) created a moralized drawing about the Spaniards’ persistent quest for gold in the Andes (Figure 1). In the picture, he represented an apocryphal event in which Greek soldier Pedro de Candía (1494–1542), called ‘Español’, and the Emperor Huayna Capac (c.1467–c.1525), called ‘Inga’, are allegedly having the first conversation between a Christian and an Inka in Cuzco. Although this event did not really happen, since Candía's encounter with Inka people was in Tumbes around 1528, the representation has cultural significance. In the drawing, we can read how the Inka asks the Spaniard in Quechua ‘Cay coritacho micunqui?’, ‘Do you eat this gold?’ To which the Spaniard answers, ‘Este oro comemos’, ‘Yes, we do eat this gold’. As Guamán Poma highlights in his caption, non-verbal communication was crucial in their meeting, as they exchanged by signs (por señas hablaron) their ideas on taste, sense and the meaning of consumption of gold. Presenting gold as an edible matter for Candía was Guaman Poma's satirical way of addressing a cultural strangeness and denouncing the dubious greed-filled obsession of conquistadors for precious metals like gold.Footnote 1 This kind of moral statement rejecting the taste for a non-nutritive substance was also relatively usual from a European point of view. Physicians at the time, for instance, would have said that this envy of possessing and even eating metals and earth was a symptom of pica or malacia, a diet disorder consisting in ingesting non-nutritive matter, associated with greed, moral deviance and a lack of judgement.Footnote 2 Therefore the drawing would likely be considered with a (dark) humour by both Inkas and Christians. Nevertheless, beyond satirical criticism, Guamán Poma's image also conveys the symbolic role that taste for mineral matter had for the Spanish social and political body. In early Spanish colonial contexts, the verb comer – to eat – and dar de comer – to feed – expressed both the political and economic need to receive favours and privileges in exchange of protection and loyalty. With Guamán Poma's drawing, we might say that Spanish expansion and the search for minerals (both metals and precious stones) were, in a way, nutritional endeavours.Footnote 3 Moreover, it was not a coincidence that gold and silver – the main metals used for coining – were labelled by Spaniards the sweetest metals and, therefore, for the sake of a cosmological homology with agricultural products, they were conceived as the purest, most temperate and most valuable ones.

Figure 1. Cay coritacho micunqui? [¿Es éste el oro que comes?] / Este oro comemos. / En el Cuzco / ‘Por señas hablaron. Y preguntó al español qué es lo que comía; rresponde en lengua de español y por señas que le apuntaua que comía oro y plata. Y acinab dio mucho oro en polbo y plata y baxillas de oro’. Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, Primer nueva coronica y buen gobierno (1615), Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, GSK 2232 4o, p. 371v. Available at http://img.kb.dk/ha/manus/POMA/poma550/POMA0371v.jpg.

In this article we contribute to the understanding of the epistemic, social and cosmological functions that taste and smell (inseparable from each other) had in the examination of minerals, particularly metals, in the vast early modern cultural area of the Spanish worlds. Our sources range from metallurgical and mining manuals to chronicles and official accounts for the Spanish Crown. We discuss, on the one hand, the work of scholars like the sixteenth-century polymath Bernardo Pérez de Vargas (c.1530–1580), physician Nicolás Monardes (1493–1588) and the priest Álvaro Alonso Barba (1569–1662), whose treatises on metals were circulated in Spanish, transmitting both colonial and European metallurgical knowledge. On the other hand, we analyse written accounts of chroniclers and royal officers who described the taste of metals such as gold, silver and copper. We have limited our research to the Spanish world's perspective, and we know that more research has to be done regarding African and Amerindian use of taste to assess metals in the colonial context.Footnote 4

We will demonstrate how taste functioned in the production and circulation of metallurgical knowledge: as epistemic marker guided by cultural values. In the first two sections we focus on the place that the subjective and embodied experience of tasting had in knowledge production about minerals, particularly metals. In the last two sections we discuss the extended meaning of mineral taste, revealing its analogical and flexible links with social values and cosmological correspondences. We show that in the Spanish world the taste of minerals was an empirical, sensory practice which served as a cultural reference for the body politic and its natural order. This argument builds on and adds to recent historiography on early modern mining, and on taste as an epistemic practice.

This article brings the anthropological history of the senses and the history of mining into dialogue.Footnote 5 The language of taste, scent and sensory experience is present in the sources of the period we examine in this article, at least those dedicated to vernacular sciences like mining and refining. There are few comprehensive studies of what taste means within the history of mineralogical science and related knowledge. Instead, much of the literature focuses on eighteenth-century engagement with the senses, and how European Enlightenment thinkers developed new ways of scientific information gathering and communication.Footnote 6 By focusing on early modern mining culture in the Spanish worlds, this article suggests that such sense-based ways of knowing were more historically rooted and geographically diverse than the traditional narrative indicates.

The early modern cartography of mining comprises diverse cultural areas such as the Harz mountains and the Ore mountains in Saxony and Bohemia, the Carpathians, the Tyrolean Alps, Iberian sites like Guadalcanal and Almaden, and the vast area along the coast and hinterlands of West Africa. In Spanish America, mining sites were abundant, from gold-mining areas in the extended Caribbean and the New Kingdom of Granada (currently Colombia and part of Venezuela), silver enclaves like Potosi in the Viceroyalty of Peru and Zacatecas in New Spain, and mercury mining in Huancavelica in Peru. The variety of early modern cultures of mining was propitious for the production and exchange of knowledge about minerals and metal transformation. The global mining rush for gold, silver, copper, mercury and iron in the course of the sixteenth century mobilized not only people and transnational markets, but also traditional practices and distinct cultural values employed in the investigation of nature. In a recent study, Tina Asmussen and Pamela O. Long have pointed out the variety of practices of knowledge that were involved in this extractive economy. In their research on mining, they addressed ‘the questions of how culture is mobilized, appropriated, deployed, and linked to the perceptions of nature, experiences of labour, practices of risk, as well as material desires’.Footnote 7 From that vantage point, historians of knowledge are able to approach mining beyond interpretations dominated by economic and technological utilitarian narratives about the rise of capitalism and the account of progressive mining extraction and chemical innovations. In this article, following such a cultural history of mining and metallurgy, we interrogate the role of taste in the context of the early modern pursuit of mineral knowledge. We contend that the sensory judgement of tasting metals was guided by a flexible cultural frame of reference with cosmological implications.

Since the seminal research produced by historian Peter Bakewell, scholarship on mining and metallurgy in colonial Spanish America has increasingly paid attention to a variety of terms and expectations, as well as labour and belief systems at work in colonial society.Footnote 8 Sensitive to this social and cultural perspective, Allison Bigelow has recently underlined the importance of the multicultural exchange of ideas, terms and naming practices in the Spanish mining worlds in order to grasp the presence of racialized thinking and the contribution of Amerindian and African communities of knowledge. By paying attention to language, Bigelow has shown the ‘ways in which miners throughout the Iberian world understood the animacy of matter and the ability of metallic objects to shape human experiences’.Footnote 9 These are aspects that might be overlooked when trying to outline a progressive or retrospective history of technological and modern scientific progress. Bigelow recalls, for instance, the way in which historian of science Modesto Bargalló in 1969 dismissed the knowledge on metals of Peruvian chroniclers and practitioners. For Bargalló, they ‘played’ with inaccurate galenic humoral terms to describe metals, such as coldness and heat, dryness and humidity, besides other notions like ‘sympathy’ or ‘antipathy’ that did not fit well with what would become the dominant chemical vocabulary.Footnote 10 Even though, from the perspective of the present, these terms might seem, at the very least, ambiguous, in a knowledge system dominated by humoral theory they were rather accurate and capacious categories addressing and ordering nature that allowed scholars, miners, chroniclers and people in general to understand mining, mineral ore and their transformation into metallic artefacts. Like Bigelow, many other scholars in recent decades have stressed the significative methodological path according to which paying attention to these humoral concepts, vocabularies and their cultural background is fundamental to avoiding oversimplifications and gaining access to the role played by taste in the early modern Spanish mining culture.Footnote 11

In this article, we address the question of how the language of taste made sense of metals and minerals in the Spanish worlds. This question is framed by a broader interrogation of how subjectivity, and particularly sensory experience in the Spanish worlds, knotted networks of expectations and produced understandings and explicative frameworks about metals. In the aftermath of the work of scholars like Lorraine Daston, Peter Galison and Steven Shapin, subjectivity is increasingly playing a major historiographical role as it gives us the opportunity to deflate present-day retrospective objectivity narratives, and to assess alternative epistemic virtues and other scientific selves in action in early modern times.Footnote 12 In that regard, in this article we aim to highlight that the witness of senses and the observation and description of mineral particulars were authoritative in Spanish sixteenth- and seventeenth-century accounts of mining and metallurgy. As Ralph Bauer has recently shown, Spanish cosmographers, natural historians and philosophers, as well as imperial knowledge institutions such as the office of the royal chronicler of the Indies, the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade), and the Consejo de Indias (Council of the Indies), built on the empirical programme of medieval Christianized alchemical tradition, which ignited sensory curiosity to shed light on the secret works of mineral nature and indigenous metallurgic technologies in the extended Caribbean and the Andes.Footnote 13 We will take into account the presence of such alchemical Christian tradition in the assessment of metals and minerals. During that period, Spanish America was the main source of silver, gold and emeralds for the world economy.

Prospecting, extracting and transforming metals and precious stones were part of an imperial project in which members of the royal bureaucracy, clerics, scholars, miners and practitioners from different cultural traditions were involved as knowledge agents. Taste had its place within this context of bullion production and knowledge making. As we will argue, knowing metals through taste was a subjective experience modulated and tuned by a variety of cultural analogies. Although the sources we will present did not propose a fixed taxonomy of the taste of metals, our article will underline that taste was guided by cultural frames of reference such as the vocabulary of food, temperature and texture, and the analogies related to nobility, baseness, utility and nourishment. This cultural frame enabled them to gather and to communicate sensory knowledge of metals.

Knowing metals through the senses

The Earth, as the servant of man, what fruit it produces, what smells, what flavours, what juices! What colors does it not engender!

Fray Luis de Granada (1583)Footnote 14Tasting mineral ore was advised for gaining knowledge about metals and finding clues for veins to be mined. ‘He who professes the art of metals does not judge as exempt any diligence that may give him greater knowledge’ (‘El que professa el arte de los metals no juzgue por escusada diligencia ninguna que pueda ocasionarle su mayor conocimiento’). For that reason, the practitioner should use his taste, ‘which discovers the purity of metals, as well as smelling does’ (‘no da menor noticia de la pureza, o mezcla de la tierra la esperiencia del gusto, que el sentido del holfato’).Footnote 15 This is how, in the book Arte de los metales, Alvaro Alonso Barba, an Andalusian cleric and mining expert writing from the Imperial Villa of Potosí, advised using taste and smell in order to learn about and access the realm of mineral matter. First published in Spanish in 1640 – translated into English in 1670 as The Art of Mettals Footnote 16 – the book rapidly became known in the Atlantic world for its detailed descriptions of the cazo or cocimiento process which improved the method of mercury amalgamation in order to refine silver ore in a more profitable manner. The process consisted of heating crushed silver ore with salts and mercury in copper cazos or large pans.Footnote 17

Barba's book on the art of metals crystallizes the Spanish American exchange of mining ideas, values and technologies between Andean indigenous communities, African people and European colonizers.Footnote 18 To codify such diverse mining practices and expectations towards metals for his transatlantic audience, Barba builds on the alchemical, mining and metallurgical tradition developed in medieval Europe and, above all, in the sixteenth century by metalworkers, gunners, preachers, physicians and alchemists such as Ulrich Rülein von Calw (1465–1523), Vannoccio Biringuccio (1480–1539), Georg Agricola (1494–1555), Benvenuto Cellini (1500–71) and Johannes Mathesius (1504–65).Footnote 19 However, despite its connection to European mining culture, Barba's treatise occupies a particular place, since it condenses New World experience and, therefore, testifies to transcultural transfers and dialogues with the mineral knowledge of colonial subaltern groups. Within this alchemical and metallurgic tradition, it is important to refer to Bernardo Perez de Vargas, an earlier Spanish author and polymath. We know little about the life of Perez de Vargas, except that he produced De re metallica (1569), a text that drew upon but also expanded the earlier De re metallica (1556) of the German humanist and metallurgist Georg Agricola. Perez de Vargas's work thus served to popularize, in the Spanish-speaking world, Agricola's earlier codification of German vernacular mining practices.Footnote 20

Both Pérez de Vargas's and Barba's treatises dealt not only with techniques to find, extract, melt and refine metals, but also with natural-philosophical examinations, popular stories and scholarly synthesis on the nature, classification and generation of metals. Barba's and Pérez de Vargas's texts have many theoretical similarities to explain the genesis of metals, such as a mixture of humoral theory, meteorological four-elements theory, and their use of the mercury–sulphur principle to describe metallurgical transformations. Instead of putting forward astrological forces as the cause of the origins of metals, as did medieval authors such as Albertus Magnus (c.1200–80), they provided explanations based on a hot-and-cold virtud mineral (‘mineral virtue’) whose heat would penetrate and mix earthy and humid matter, and whose cold would harden it. This tenet followed Aristotelian meteorological theory, according to which metals would spawn and grow in the earth like plants, fuelled by subterranean heat and exhalations. Metals were treated as composite matter, formed by the action of the elemental qualities: hot, cold, dry and humid.Footnote 21

Regarding the senses, both Pérez de Vargas and Barba mentioned their role when prospecting, distinguishing and describing mineral matter.Footnote 22 As Bigelow asserts, before the advent of spectrometre technologies, ‘miners sorted and named metals using data they gathered from their senses’.Footnote 23 Earlier we quoted how Barba advised that whoever professes the art of metals must use and exercise the senses to learn and increase mineral knowledge. Even though ‘the true knowledge of what species the metal is, depends upon the essaying of the mineral ore’ (‘el verdadero desengaño consiste en el ensaye de las venas’), Barba and Pérez de Vargas still considered the senses the initial, unavoidable way to know mineral matter.Footnote 24 While an assayer or mint officer ultimately tested the quality and nature of mineral ore with the assistance of fire and with weight and measuring tools, miners, prospectors, cateadores (dowsers) and baquianos (local experts) used their set of sensory skills to pick up signs and clues in the landscape and among the ore they collected.Footnote 25

As Warren Dym has shown for German areas, early modern mining culture was expressed and lived in an outdoor setting, in mountainous landscapes, through forests and rivers: mining practitioners were like hunters and diviners, seeking concrete, experienceable traces of the hidden bounty of the earth.Footnote 26 Similar realities can be found in Spanish mining and metallurgical culture, where people were acquainted with practitioners coming from German areas, or with experts like a zahorí, an interpreter of the landscape who was able to find hidden sources of water, metals and treasures through sensory signs.Footnote 27 Additionally, in the Andean colonial context, the cateadores (a Hispanized term from Quechua çatticcayani, having fallen inside a deep thing, and çattita, a wise man who understands through experience and is versed in all things) were skilled people who knew how to search for and find hidden mines.Footnote 28 Barba described their sensory acuity in the following terms: ‘to look in mountains for veins of hidden metals, using the indexes and signs of the veins, which they who are called cateadores know from experience in this exercise’.Footnote 29

Among the senses involved in mineral and metallurgical knowledge, sight was for Barba the most reliable (‘el más cierto desengaño de los sentidos’).Footnote 30 He reduced all minerals to eight colours – white, black, grey, blue, green, yellow, red, purple – and their mixtures. As Allison Bigelow has highlighted, Barba also based his rather intricate taxonomy of silver ores on three racialized colour differences taken from colonial vocabulary: pacos (from Quechua ppaqu, reddish silver ores), negrillos (‘little black ones’, for black silver ores) and mulatos (mulattos, for silver ores between the black and red categories).Footnote 31 With sight, miners could also discern particular forms in plants or cliffs surrounding a vein, or also perceive from a distance glittering signals indicating mineral soils and precious metals, like vapours or particular glow effects in hills and forests.Footnote 32 But, as the sight could be fooled, especially inside the mines, it was necessary to involve all sensory practices that could reveal the secrets of the earth, such as touching, tasting and smelling.

Similar to what Pamela H. Smith has argued for places such as Central Europe, sensory perception of landscape shaped the practical knowledge of Spanish early modern mining.Footnote 33 Through sight, smell, taste and touch miners could gather clues to determine the kind of soils, the characteristics of the mineral ore and the place where a metal could be found.

Tasting minerals

Smell was considered appropriate for determining the nature of specific materials. In his De re metalica, Pérez de Vargas analyses the taste and smell of metals together, since, on the one hand, smell is understood as a consequence of taste (‘el olor es secuela del sabor y manera de rastro suyo que deja’) and, on the other, one can better determine and know a taste through the vaporous odours of ores and melted metals.Footnote 34 Additionally, according to medical humoral theory, smell and taste were signs of hot and dry qualities in matter, and were supposed to be less noticeable in cold and humid things.Footnote 35 In fact, taste is as related to smell as to touch, since taste can also be described with temperature and texture perceptions. This was the case for the taste of metals, since a hot metal like copper was accounted as having a harsher taste than mercury, which was considered a cold metal with imperceptible taste. As we will see in this section, the taste of metals was associated with neat oppositions or structuring polarities between fetid and nice odours, hot and cold temperatures, sharp and soft textures.

For both Barba and Pérez de Vargas, the variety of odours arising from the soils makes mineral nature an admirable thing to be known. They refer to several experiences and procedures in which tasting and smelling mineral ore were involved. For instance, a common experience among Andean miners was to smell pieces of mineral ore that they did not recognize, acknowledging the epistemic potential of this sense.Footnote 36 Although the general judgement was that mineral matter tended to have bad taste and smell, miners knew that rare prerogatives in their art could be found. In fact, the clays from Nata in Panama, Estremoz in Portugal and Malacca in East India were judged as having a pleasant fragrance. Good smell (olor bueno), of high esteem (de admiración), as well as exhalations with a gentle and peaceful warmth (calor apacible) were credited among Spanish miners as sign of potential richness of rocks and soils (‘señal de riqueza que tienen sus piedras, o tierras’).Footnote 37 For Barba, certain gold and silver mines did not stink – something that Bernardo Pérez de Vargas had stated too – and these mines could even have a nice smell. For instance, following Georg Agricola, Barba wrote that in the Saint Sebastian mine, in Marienburg, there used to emanate such a sweet smell that Prince Henry of Saxony thought it was similar to the exotic scents from India he was acquainted with, which made him dream about the smell of Paradise.Footnote 38 Barba validated this anecdote with his own Andean experience of the good scent of some silver ores in Peru: ‘a gentle smell comes out of the mines of metals which are called Pacos’.Footnote 39 But this was rare: in most cases, metals had a bad smell and a bad taste because of their distempered complexion and their mixture with sulphur and other ‘mineral juices’.Footnote 40 Fetid-like animal excrement, pestilential, causing death, thick, upsetting and similar to a ‘cellar full of must, when it is boiling, with a serious and heavy stench’ (‘bodega llena de mosto, cuando está hirviendo, grave y pesado’): those were usually the kind of smells miners had to perceive and take care of, because they could be signals of mortal vapours.Footnote 41 Barba tells different stories in which bad smells and poisonous exhalations had killed indigenous miners and made work impossible, forcing them to abandon such locations.

Like modern geologists who still lick or taste rocks and mineral ores to better appreciate their properties, Barba recommended the ‘experience of taste’ in order to have full notice about the ‘purity or mixture of the soil’: ‘The curious miner ought to make trial by tasting’.Footnote 42 The learned priest in Potosí emphasized that since all minerals are commonly dry and hot, bad-tasting earth can be taken as a good sign for the existence of metals in underground. In that regard, polymath Perez de Vargas also underlined the fact that, because of the presence of sulphur, all mineral tastes were more or less salty and acute (agudo), while smells were generally fetid. However, despite the fact that all metals had a degree of bitter acrimony, the taste difference between them was so clear that gold and silver were considered sweet and with less stench because they did not have as much ‘malign mixture of sulphur’ as other metals (‘la mezcla de malicia de azufre’).Footnote 43 Therefore – Pérez de Vargas emphasized – we must understand that, although some minerals might be called sweet, they rather stink and have a bitter (amargo) taste. Mineral sweetness was, then, a relative term in a line of bad and not too bad smells and tastes.Footnote 44

Over the centuries, thinkers have put forward divergent assessments of the epistemic value of taste. For Aristotle, the senses of taste, smell and touch were understood as not capable of discovering the true nature of things, when compared with sight and hearing.Footnote 45 But since the thirteenth century at least, as Charles Burnett showed years ago, this was far from being unanimously agreed upon at the time. In late medieval manuscripts like the Summa de saporibus, taste had acquired pre-eminence and superiority, as the adequate sense for true knowledge, because it was able to transcend superficiality – a capacity that other senses would lack.Footnote 46 Spanish physician Juan Huarte de San Juan (1529–88) provided a nice case to understand such a sensorial paragone. A person with sharp sight, Huarte suggested, is rarely bewildered by things with very different aspects, but when many things are similar – and such was the case of mineral ores – to perform right discernment gets harder:

if we set before [someone with] a sharp sight, a little salt, sugar, meal, and lime, all well pounded and beaten to powder, and each one severally by itself, what should he do who wanted taste [que careciese de gusto], if with his eyes he should be set to discern every of these powders from other without erring …? For my part I believe he would be deceived.Footnote 47

For early moderns like Huarte, there were at least six different tastes, although other authors would enumerate ten or even eleven. These were catalogued in a sort of line range or latitude – to use a term common to galenic thinking – between fetid and peaceful smells, hot and cold temperatures, and sharp and smooth textures, enabling tastes to keep a relational and contiguious order between them. Here we list the most common order in which tastes are explained by Spanish and New World physicians with the type of food they associated it with: acrid (acre), also called acute (agudo) or mordant (mordaz), like the taste of garlic and chilis; bitter (amargo), like almonds and lupins or altramuces or chocos; salty (salado), like chickpeas; astringent (astringente), for some authors also called austere (austero) and acerbic (acerbo), like capulín (prunus salisifolia) and acorns; vinegary (avinagrado) or sour (agrio), like vinegar and lemon; fat (graso), like lard, although some authors did not consider it a taste, but a consistency or tactile aspect; sweet (dulce), like honey; insipid (insípido), like pure water, which, however, was contested as a taste.Footnote 48 Beyond the realm of expertise, this rough classification of taste was a shared knowledge, and people in general understood the rules, meanings and mechanisms to apply it in their everyday life. For example, in his itinerary through the Caribbean and the northern Andes, the Florentine merchant Galeotto Cei (1513–79) was able to distinguish the different properties of cultivated and wild guava thanks to their special taste: the latter was astringent and, therefore, it was appropriated to provoke constipation and treat looseness of the bowels during a tropical journey. Another example can be found in the testimony of chronicler and natural historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo (1478–1557), who stated that adequate guavas recommended for constipation were those that were not ripe, because of their astringency.Footnote 49 Taste was presumed as a way of knowing: people could rely on it, since their tongue could tell them what the world was like.

For medical practices, identifying the taste of food and medicines with a certain degree of precision allowed healers to know their properties and elemental qualities and, by extension, to determine their appropriate use for a particular human complexion, the treatment of an ailment, the right time of the year for their consumption, or the best way to include it in a diet, among other variables.Footnote 50 In contexts of traveling, commerce, warfare and cultural encounters, taste could be of great use for early modern Spaniards. Besides distinguishing themselves from others through their ideas about what was socially distasteful and avoidable, the global expansion of European monarchies compelled Christians to test their preferences and palates. Taste was then exerted to decipher the virtues of novel plants and mineral particulars present in different materia medica and foodstuffs which challenged their taxonomic models and their gustation.Footnote 51 Physicians, artisans and practitioners of mining and metallurgy were certainly efficient at identifying and naming the tastes, nature and virtues of edible and non-edible matter in order to inscribe it within their bodies of knowledge and ways of living.Footnote 52

Like food and medicines, minerals also had tastes to examine, although with less diversity. Almost all minerals were salty (salados) and bitter (amargos), depending on how much sulphur they contained. Even though, in our sources, there is no explicit attempt at a systematic mineral taste classification, the period actors themselves judged and acted following the polarities or oppositions between hot and cold (temperature), sharp and smooth (texture), or fetid and agreeable (odour). At one extreme, we should locate the powerful stench of sulphur, the hottest and most acrid mineral. At the other extreme, we can situate mercury as the most humid and cold one. Associated with sulphur, and often accompanying copper and iron, Barba says that ‘rock-alum’ is ‘mightily astringent’ (virtud de constreñir), and ‘copperas’ (copper sulphate, vitriol or, for Barba, caparrosa) ‘has a biting taste, with a sour and astringent quality’ (mordicante al gusto, áspera y constrictiva).Footnote 53 Given its cold and moist nature, Pérez de Vargas affirms that it is difficult to perceive the taste of lead and tin – soft metals.Footnote 54 Copper and iron, as they were classified as hot, could be directly recognized by their acrid, acute (agudo) or bitter (amargo) taste.Footnote 55 Silver and gold, as the most tempered metals, were credited as being the sweetest.Footnote 56 Gold was at the pinnacle of taste: ‘Gold smells and tastes well, by reason of its most excellent temperature; or at least, it neither smells nor tastes ill.’Footnote 57

Even though the taste of minerals and metals could be placed somewhere between the polar ranges of hot–cold, agreeable–fetid, smooth–sharp, they were also movable thanks to human agency or due to their specific underground origin. Ultimately, the transformation and variability of mineral matter were the main pursuit of alchemy and metallurgy. According to humoral theory, all bodies and mixtures have a complexion that could change by altering their inner heat or humidity. Climate, nutrition, exercise, emotions and ageing were, for instance, means by which persons could undergo changes in their complexion.Footnote 58 As well as foodstuffs, metals could be altered and transformed by means of fire.Footnote 59 However, although technical means were capable of altering the taste of metals, their taste could also differ from one place to another. According to Spanish royal chronicler Juan López de Velasco (c.1530–98), his informants from Río de la Plata provinces had written to him that their copper was sweet (dulce).Footnote 60 In a different account from late 1560s, Juan de Echagoyan, a former judge of Santo Domingo, wrote that La Española copper was vinegary, but that it could be sweetened.Footnote 61 The same process of turning copper into a sweeter metal appeared again in 1621 in a proposal made by the regidor of Jerez (Spain) Manuel Gaytán de Torres to the Spanish Crown for the exploitation and refining of copper mines in Venezuela.Footnote 62 Therefore copper could move by human agency in the polarity of taste, from acrid or bitter (hot) to vinegary (less hot) and to sweet (tempered). In his journey through Spanish America during the 1660s, the Syriac priest Elias al-Mûsili described that when silver ores were too earthy or cold, miners and assayers were able to temper them by adding copper, but if they thought they were too hot, they would add lead to make it sweeter.Footnote 63 This capacity of taste to identify the properties of metals is significant, since it confirms that taste was an epistemic marker and was used to assess and project processes of alloying, refining and assaying metals.

As Pamela H. Smith has argued, ‘the polar oppositions of Aristotelian qualities – hot, dry, wet, and cold – were a fundamental structuring framework for all knowledge – practical and otherwise – in early modern Europe’, as well as in Spanish America, we should say.Footnote 64 As we have seen, although there was not an explicit system for the variety of metal tastes where mobility was the rule, we want to suggest that they were employed as sensory and epistemic markers within the polarities of hot and cold, fetid and agreeable, and sharp and smooth. This taste polarity enabled early modern people in the Spanish worlds to determine material properties, potential metallurgic transformations and the relative value of minerals and metals, going from acrid and bitter taste to sweet and insipid; from the most harsh, hottest tastes of copper, iron and sulphur (with salty, bitter and acrid tastes), to the most humid and cold tastes of mercury, tin and lead granted as less sapid. Silver and gold were put in the middle and most valuable place, as fat, sweet, temperate metals. Taste was therefore an operative way to understand, describe and transform the metals.

Waters, metals and geographical descriptions

Aside from metallurgical and the mining treatises, it is difficult to find references to the taste of minerals and metals. The tacit nature of knowledge based on taste is an explanation for this scarcity. On the mining ordinance (ordenanzas mineras) – a gubernatorial regulation that almost every jurisdiction promulgated through the modern age in the Hispanic worldFootnote 65 – the taste of minerals was not even mentioned, because the ordinance was made for ruling the ownership and exploitation of the mines, not for discovery or analysis. Fernández de Oviedo did not mention the use of taste for metalworks, even though he wrote a detailed description of the search for and mining of gold.Footnote 66 In the Cartas annuas of the New Kingdom of Granada, the Jesuits did not record information about this subject, nevertheless they did mention how gold mining was done in the province of Antioquia.Footnote 67 The few references beyond metallurgic treatises we have found so far are related to the connection of waters and metals. Interestingly, as we will see, tasting water was an indirect way of gaining and communicating knowledge about the presence and properties of metals in specific places.

Here again, Barba opens the way: metals ‘communicate to water their qualities and virtues’ (‘comunican a las aguas sus calidades y virtudes’). When they get in touch, he explains, waters receive the ‘very subtle spirits of metals’ (‘espíritus sutilisimos del metal’). From that communicative principle, says Barba, a variety of flavours, odours, colours and medicinal properties can be found in streams and springs.Footnote 68 Barba also describes several workshop experiences in which metals communicate their taste to water. Any sort of ore, he says, would imbue its taste easily in a glass of water, and the infusion will go even faster if it is boiled twice: afterwards one can taste it and discern with certainty the taste of the minerals.Footnote 69 This experience turned out to be for him the best way to know whether alum and copperas or vitriol were present in the pieces of ore he wanted to refine: the acrid or sour taste of water would be a clear sign of the presence of those sulphurous minerals.Footnote 70 Bernardo Pérez de Vargas also recognized this indirect method of finding or identifying metals by tasting water. In the case of copper, for instance, he described how this mighty metal infused underground waters that pass through its veins, turning them into a bitter, deadly and abominable liquid. His advice: do not try to drink wine in a glass made of copper.Footnote 71

Records coming from the Relaciones geográficas de Indias inform us on how civil authorities in Spanish America described the mineral taste of their rivers and streams. These records are privileged sources for understanding how the use of sensory knowledge of metals through smell and taste was also present in people who did not exert mining or metallurgic practices. The Relaciones geográficas were conceived by the Spanish Council of Indies in the 1570s and 1580s as an attempt to standardize the natural, historical and political descriptions of Spanish kingdoms through a fifty-item questionnaire composed by royal cosmographer and chronicler Juan López de Velasco (1530–1598). This administrative and epistemic project for the entera noticia (‘whole description’) of the New World united local agents in the Indies with collection and calculation centres in Europe.Footnote 72 The questionnaire was received in every town and city, and local authorities should answer them with the help of the most experienced people who could know some of the answers, because of their training or their antiquity in the place. Since the Relaciones geográficas were based in very specific questions, they enabled people to verbalize ideas and practices that were part of everyday tacit knowledge.

We have gathered different answers from several parts of the continent to provide a quick and wide perspective on how descriptions of mineral taste were made, starting with the taste of waters. In Guatemala, in the provinces of Verapaz and Zacatula, it was reported that some waters coming from the mountains were gruesas – which is thick, raw: hard waters – because they were not warmed by the sun, while others were ‘terrible, for they pass, I think, through veins of iron or something ill and of bad flavour’.Footnote 73 In other records coming from New Galicia, New Spain and Quito there were references to the water that runs through deposits of gold or silver: in those two cases, the waters were judged as buenas, sanas and delgadas – good, healthy and thin: light waters.Footnote 74

Following the same indirect method of tasting metals through the water, Franciscan chronicler Fray Pedro Simón (1574–1628) wrote in his Noticias historiales (1626) about the quality of water as a sign of gold mines in the Paeses province, by the Magdalena river: ‘To what it seemed to me, and to others more trained than me who also agreed, when I was in the province of these Indians, there were good signs of gold mines in many parts, as the delicate [delicadas] and healthy [saludables] waters showed it’.Footnote 75 In a context of Spanish expansion and colonial settlement, this first-hand testimony is exemplary because it explicitly states that good waters could be true signs of undiscovered and very much desired gold.

In the examples we have shown in this section, the adjectives used by common people for the water that runs through gold and silver veins were ‘good’, ‘healthy’ and ‘thin’ (light). The informants and the chronicler did not use ‘sweet’, as metallurgic practitioners would do. However, this might be explained by the fact that informants were oriented towards the healthy conditions of their inhabited environment, while miners and artisans were describing the temper of their ore and metalworks. Additionally, the principle of light waters is that they are sweet, even if they are not properly sweet as sugar (sweetness, as we have already said, was also a relative term that meant temperate). Moreover, good water was supposed to be ‘without colour, smell or flavour, and must be seen by the sun’, because its heat tempers the water and makes it digestible, less raw, and healthier.Footnote 76 Therefore the lack of a specific taste in the water was a sign of quality. For the same reason, metals like silver and gold were also credited as purifiers of water for their temperate and ‘sweet’ quality, in contrast with other metals like copper or iron.Footnote 77 In the Relaciones geográficas we have chosen, the association of thin, temperate and healthy waters with the good nature of metals uncovers a cosmological analogy with symbolic effects that gives us the occasion for a final consideration on the taste of metals in the Spanish worlds.

The cultural and cosmological breadth of mineral taste

Let us finish this analysis by stressing the natural-philosophical and symbolic dimensions of mineral and metal tasting through the exemplary cases of gold and iron. As we have seen, the good taste of gold and silver was explained from the minimal quantities of sulphur in their composition. While gold was described as having the best and purest taste, iron was assessed as having a bad, acrid taste because it was mixed with more sulphuric minerals. Pérez de Vargas described its nature as a ‘bastard metal’ (‘metal bastardo’) made of an ‘earthy, thick and strong substance’ (‘de una sustancia terestre, gruesa y fuerte’), associated with decay and instability by the rustiness it could engender (‘cría orín y herrumbre’).Footnote 78 The famous Sevillian physician Nicolás Monardes (1508–88) described this traditional opposition in his Diálogo del hierro, y de sus grandezas (1574): ‘gold is made from clean and pure origins, which makes it splendid, radiant and beautiful, and iron, made of coarse and impure origins, is ugly, black and dark’.Footnote 79 The assumed opposition between gold and iron based on its externalities and sensory qualities projected a hierarchical logic rich in cosmological analogies and symbolic consequences. However, given the benefits of iron in daily life and the excesses committed for the spell of gold, early moderns like Monardes challenged such categorical opposition and, by extension, stressed the limits of assessing metals through taste, as well as the expectations and belief systems that this way of knowing could generate. By revealing the functioning – and ironical conversion – of this hierarchy, we will outline the cosmological correspondences and variations that the tastes of metals could entail.

As Allen J. Grieco has shown, during late the medieval and early modern periods the classification of the vegetable world was derived from Albertus Magnus's canon; in this classification there were five distinct categories: (1) trees, shrubs and bushes that produce fruit; (2) grains; (3) herbaceous plants; (4) plants with edible roots; and (5) the acrid group of garlic, onions, leeks and shallots. Generally, it was thought that natural products with better taste – the sweetest – were those generated by trees, and then, in a descending scale, the rest. The worst taste was acrid. According to this perspective, proximity with the ground was considered negative and less valuable. Consequently, taste for certain foodstuffs could have social assumptions. In the vegetable scale, fruit from trees were worthy of the nobility, while the last group, garlics and onions, was assumed to be suitable for peasants. Additionally, it was thought that the best fruit to harvest were those at the top of trees, because the sap that nourished them was already filtrated and less earthy, unlike the sap received by fruits located at the lowest parts of plants.Footnote 80 Fruit that moved away from the ground and closer to the sun was usually preferred because of its improved flavour. Analogically, it was also supposed that, according to a vernacular astrological correspondence – also developed by Albertus Magnus and the Christianized alchemical tradition – the sun and other celestial bodies, with their rays, heated and penetrated the element of earth, modifying it and creating metals in its entrails.Footnote 81 Even though sixteenth- and seventeenth-century scholars like Pérez de Vargas, Monardes and Barba disavowed this astrological explanation for the origins of metals, associations between metals and astral bodies were still frequent, especially when appraising metals. In the corpus of the Relaciones geográficas we find cases in which the informants explained that the presence of gold in their territories was due to the effect of the sun.Footnote 82 In this manner, gold was considered the most perfect among metals for its correspondence with the sun, the value of silver compared to the splendour of the moon, while iron received the influence of Mars. These analogies between metals and celestial bodies were also carried to a social level. Gold and silver, for their temperate nature, sweetness, purity and shininess, were adequate for noble matters, whereas the ill complexion of iron was suitable for lower, but profitable, deeds related to the mechanical arts and peasant work.

In the complex web of cultural associations in the early modern Spanish world, the analogies of the sunshiny gold prompted by the sense of taste were abundant. For Barba, for instance, another reason for gold having a good taste was its fatty complexion.Footnote 83 This connection with a fat quality had sense in the scale of taste because sweet and fat were adjacent flavours.Footnote 84 By means of analogical thinking, connections between sweetness and fatness gave gold a symbolic place within dietetic thinking, according to which the most nutritious foodstuffs were fat and sweet.Footnote 85 Besides, from late medieval times, fat (graso, pingüe or untuoso) had strong symbolic links with wealth, and was synonym for abundance, copiousness and fertility.Footnote 86 In that sense, we might say that gold was the best nourishment, perhaps not for the human body, but for the social body.Footnote 87 As Guamán Poma's satirical drawing conveys, gold fed the early modern Spanish body politic (Figure 1).

Despite the fact that metals could be invested with a high or low hierarchy according to their specific place within the polar range of tastes, metals could also receive different meanings when assessed from other points of view, such as from the benefits they offer to humans. In Monardes's Diálogo del hierro, y de sus grandezas the symbolic and cosmological associations derived from the taste of metals were questioned. The sulphur-and-mercury theory about the origins of metals gave Monardes the opportunity to assert that iron ore was not only generated from the same physical principles as gold and silver, but that it was actually the most excellent (‘el más excelente’) of metals, ‘because iron is more useful and necessary than all the other metals’ (‘porque del tenemos más aprovechamientos y más necesidad que de todos los demás’).Footnote 88 The doctor in Monardes's dialogue affirms that the zeal for gold and silver has created scarcity and overrated prices in the Spanish world. Instead, iron appears as a reminder of the abundant, cheap and useful means provided by nature and fashioned in sundry ways by human ingenuity, not only for its role in the making of tools, but also for its medicinal properties treating ailments. For Monardes, the sense of utility can be taken as the shifting point and limit to taste as an epistemic and symbolic marker for metals. Dissociated from the values conferred by taste, gold shows its dark side in the greed and plunder it yields, while iron shows its splendor in all the help it gives to labour and the maintenance of life. Monardes questioned the idea that metals could be appreciated by the external forms gathered by the senses. He moved away from straightforward analogies, and preferred to go beyond the values associated with the colour black, rustiness and the acrid flavour. Instead, from an ironical or paradoxical appraisal, he conceived of iron as the actual gold. For Monardes, iron was the best metal because of its multiple uses – a remedy for melancholy and infertility, and a matter used in navigation for exploring new lands. Even though it was not of the most precious complexion, its practical functions had more weight than its composition. As historian Antonio Manuel Hespanha has stated about the juridical order in the early modern Iberian world, less perfection and subordination did not imply less dignity, but only a specific place in the order of Creation. Therefore each entity was supposed to play its role in the social and natural order adequately and honourably, according to its nature.Footnote 89 In that sense, the values of usefulness and cooperation underlie Monardes's paradoxical appraisal of iron's dignity and his rejection of the overrated taste for gold and silver: ‘Iron is profitable for agriculture and country labours: to benefit estates and … things so necessary and beneficial for everyone, since the arts of the countryside support and sustain all the states of the world’.Footnote 90

According to their taste, metals could assume a network of cosmological and symbolic values entailing a hierarchy. But the taste conferred on a specific metal was neither a determination of its meaning nor certainly the only way to understand it. From the perspective of utility and ethical considerations of a good life, metals were assessed differently, as Monardes proposed with his appraisal of iron. By considering the cosmological breadth of the taste of metals we have pointed out both its potential and its limits.

Conclusion

In this article we have examined the role of taste in Spanish understanding of metals during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. References to tacit knowledge entailing tasting metals are not abundant in historical sources. In mining and metallurgic treatises, sight, measurement and assaying methods were preeminent for recognizing, classifying and describing mineral matter. However, our analysis has shown that through taste it was possible to gain access to other forms of knowledge about metals. The language of taste was mainly structured by an Aristotelian and galenic vocabulary of elemental qualities and humoral differences. The fact that discussions of the taste of metals and minerals appeared mostly in metallurgic and mining treatises implies that it was the subject of a training process and a specialized knowledge that could be obtained in practice. Practitioners like Andean assayers, miners, zahoríes, cateadores and baquianos would have had to use their refined palate in order to better grasp particularities and differences. Naming and describing mineral tastes enabled them to gather sensory clues in the landscape (like tasting waters to determine the presence of metallic veins), discern the composition and properties of mineral matter, and envision potential transformations in the metals they worked with. Indeed, taste was as useful for knowing as for making. Tasting and assigning taste to metals oriented human ingenuity on how to transform them through the force of heat and the mixture with other metals, as happened in the case of food and cooking. Taste was granted as a rather reliable way of knowing in the Spanish worlds.

Although mineral and metal taste had a resemblance with everyday ways of naming foodstuffs, it was applied in a relative sense. The taste of copper was deemed acrid or bitter, but it was not bitter as an almond; gold was sweet, but never as sweet as sugar, and so on. Barba and Pérez de Vargas insisted that all metals were fetid and rather sharp to the taste. The different tastes of metals, from sweet to acrid, should then be understood as an effort to inscribe mineral stuffs within the polarity of temperature (hot–cold), texture (soft–sharp) and smell (peaceful–fetid), with the aim of organizing and discerning their subtle particulars and their technical potentials. This operation necessarily mobilized evocations of and associations with symbolic values of taste and distaste, social distinctions between nobler and lower metals, natural-philosophical comparisons with plants and humans, and cosmological thinking on matter.

In this article, we have been able to show how, in the vast geography of early modern Spanish culture, the subjective and embodied knowledge of mineral taste was mediated by moral and social considerations on the body politic, and validated by cosmological correspondences. Knowledge provided by taste conferred sundry symbolic values that reinforced the cultural significance of metals, even when not straightforwardly connected with mining, metallurgy or alchemy. However, such a wider framework of taste triggered irony and criticism from persons like Nicolás Monardes and Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala: taste for metals could be scorned as overrated when refined palates did not consider utility and good life in their judgements.

Acknowledgements

This article was supported by research funding from Universidad EAFIT (Grant No. 952-000023 Ingenio Indiano: ambientes del conocimiento en el trópico americano) and from Universidad de Antioquia, CODI (Grant No. 2021-40710 Orden y anomalía. La taxonomía de los alimentos americanos según los europeos. 1492-1640). We are grateful to Marieke Hendriksen, Alexander Wragge-Morley and Allen J. Grieco, who offered insightful feedback on an earlier version of this article. We thank César Lenis Ballesteros, Sebastián Gómez González, Óscar Calvo, Ignacio Uribe, Pablo Castro López and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and help in developing and clarifying key ideas in this article.