Introduction

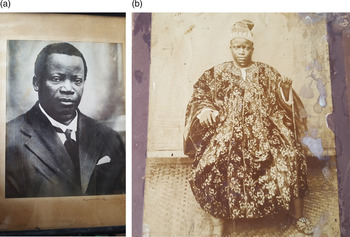

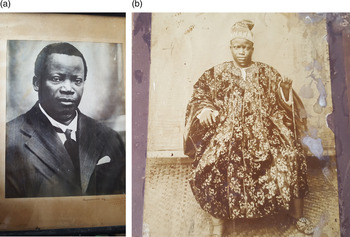

One of the results of colonialism in Nigeria has been the evolution of a group of local intelligentsia with a discrete social identity. The nationalist and political activities of the group have received the attention of scholars. However, with a few notable exceptions (see Ọlabimtan Reference Ọlabimtan1974a; Ogunṣina Reference Ogunṣina1992), the same cannot be said of their contributions to the growth of literary tradition in Nigerian indigenous languages. This essay helps to fill that vacuum. The article hopes to contribute to the growing literature on local intellectuals in Africa. It examines the trilogy of a Yoruba poet, Denrele Adetimikan Ọbasa, a member of the local intelligentsia in Ibadan, Nigeria (Figures 1a and 1b).

Figure 1 Denrele Adetimikan Ọbasa.

I begin with an overview of Ọbasa's biography and those factors that combined to shape him as a poet and local intellectual, because a meaningful discussion of his poetry demands such an examination. Then, the essay proceeds to discuss the social value in the poetry of Ọbasa, which, as revealed in the article, is based on the Yoruba world view and philosophical thought enshrined in the folkloric material that formed the basis of his poetry. The approach adopted in this study is multidisciplinary, combining historical analysis with sociological, cultural and philosophical perspectives.

The poet and his background

Denrele Adetimikan Ọbasa was born a prince of the Giẹsi ruling house of Ile-Ifẹ in 1879 to Prince Awolẹ Ọbasa and his wife Fọlawiyọ, who were working in Lagos at the time of their son's birth. After his elementary (primary) school education (1886–90), the young Ọbasa gained admission into the Baptist Academy in Lagos in January 1891, and successfully completed his high school education in December 1896. Due to his parent's limited financial resources, Ọbasa could not travel overseas for his post-secondary education, like some of his contemporaries from wealthy families. During this time, there were no post-secondary institutions in Nigeria: the first ones to be established came fifty years later, with the foundation of Yaba Higher College (now Yaba College of Technology) in Lagos in 1947 and the University College Ibadan (now the University of Ibadan) in 1948. So, Ọbasa decided to apply for positions with companies based in Lagos. But, while he waited for a job offer, Ọbasa's parents advised him to learn some form of trade. Ọbasa agreed, and he signed up as an apprentice with a local printing press and a furniture maker in Lagos. Although Ọbasa successfully completed his training in both, he loved the printing press more; that probably accounted for his decision to establish a printing press later in life.

Ọbasa learned the art of editing, printing and publishing in Lagos under a Sierra Leonean Yoruba ex-slave returnee, Mr G. A. Williams. Ọbasa dedicated a substantial section of the poem Ìkíni (‘Homage’ or ‘Greetings’) in his first book of poetry to the role Mr Williams played in his training as an editor and printer:

Ọbasa was nearing the end of his training in printing and carpentry when he received his first job offer in December 1899 as a sales manager with Paterson Zochonis (PZ) in Lagos, a British-owned company and manufacturer of healthcare products and consumer goods founded in 1879. Ọbasa was later transferred to Ibadan in December 1901 as the store manager for the newly opened branch office of the company. He remained in the Ibadan branch office until December 1919, when he resigned after twenty years of unbroken service, to establish his Ilarẹ Printing Press (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Ọbasa and his workers and apprentices at Ilarẹ Printing Press.

Ọbasa's choice of Ibadan as the location of his printing press was strategic – none of the other printing press companies already in existence in Nigeria had an office in Ibadan. They were all based in Lagos and Abẹokuta. So, with the opening of Ilarẹ Printing Press in Ibadan, Ọbasa was able to draw patronage from Ibadan and other major Yoruba cities. The press flourished and became well known, because of Ọbasa's multidisciplinary qualities as creative writer, public intellectual, businessman, news editor, advertiser, and above all artisan. All this affected his popularity as a writer and the success of his printing business. Later, other printing press companies were founded: for example, Lisabi Press in Ibadan in 1930 and Tanimẹhin-Ọla Press in Oṣogbo in 1935. It was in the midst of the competition from other printing companies and deteriorating health that Ọbasa died on 16 May 1945.

What are those aspects of Ọbasa's biography that make him an outstanding Yoruba poet and local intellectual? One can say that the greatest influence on Ọbasa by far was his love for, and interest in, Yoruba language and cultural practices. Ọbasa perceives his task as ‘that of “writing culture”, writing the oral traditions and the language of his people to recover an art and knowledge that he felt to be endangered’ (Nnodim Reference Nnodim2006: 158). For that singular act, this essay recognizes Ọbasa as a public intellectual within the colonial Yoruba cultural environment because he strategically chose to write in Yoruba instead of English, as he wanted to address his immediate local audience.

Although Ọbasa was championing the cause of Yoruba language and the preservation of oral traditions, he was, however, doing so in print, which meant that he had to find ways of connecting with an audience that was not co-present. According to Nnodim (Reference Nnodim2006: 154):

the issue of turning towards, giving shape to, and addressing audiences was particularly pertinent at those pivotal historic trajectories, when the introduction of writing, print technology and electronic mass media enabled verbal artists (and early writers) to go beyond the local towards conceptualizing and addressing potentially unlimited, unknown audiences (and readers) through print expression and through a new kind of mass-mediated secondary orality.

Thus, in the case of Ọbasa, the delivery of his poems in print did not engender hegemony of the written word and did not displace the oral as an obsolete mode of literary expression; rather, it opened up possibilities for numerous creative forms of coexistence and interfaces of the oral and the written. Therefore, Ọbasa, through print technology, was able to connect with his audience through a form of poetic expression that is semi-oral and semi-written, a type of genre that oscillates between the written and the oral.

Because Ọbasa's poetry is situated at the intersection of writing and orality, the audience he addresses in some of his poems is a thoroughly local one, interpolated in his poems through a proliferation of local terms of greeting:

In this excerpt, the encounter between Ọbasa and his audience is ‘metaphorically imagined as “knocking on people's doors”, as seeking for permission to enter’ (Nnodim Reference Nnodim2006: 159). He addresses an imaginary audience directly with his interpolation of face-to-face greetings directed at different sets of people in society. In other instances, however, he envisions a larger audience, seeking his audience not only among the different sub-groups or dialects of the Yoruba with whom he inhabits the shared space called Yorubaland, but among other languages whose speakers are found in that same society.

Here, Ọbasa is trying out numerous ways of addressing an imagined audience, in numerous languages and dialects. This demonstrates not only a wish to connect directly with a large audience of readers in a quasi-oral fashion, but also a recognition that his own language and language variant (Ọyọ or Ibadan Yoruba) was among many: a cosmopolitan perspective. And Ọbasa shows off his cosmopolitan credentials and linguistic proficiency by presenting greetings in all of them, with great expertise too.

Ọbasa's choice of Yoruba language for his writing assisted him in connecting with the generality of the people in his locality, and he became very popular. That popularity paid off when his books were included in the reading list for public elementary schools in the Yoruba-speaking region of south-western Nigeria. Ọbasa's books fit well into the early childhood education curriculum because, as a poet, the writer was concerned with instilling moral values in children and young adults, using his poems to instruct and correct, with the ultimate aim of promoting acceptable good conduct in society.

Because of Ọbasa's commitment to Yoruba culture and tradition, he made a clear case in the prologue (Ìjúbà) to the first collection in his trilogy for the study of the oral artistic traditions of the Yoruba people, which he claimed were comparable to the works of renowned authors such as Homer (the Greek poet), Longfellow (the American poet) and Shakespeare (the British poet and playwright):

Púpọ̀ nínú wọn (ohùn ẹnu Yorùbá) li ó farajọ ti awọn àròfọ̀ àwọn ọ̀jọ̀gbọ́n ti ìlú òìbó tí a ń kọ́ni ní àwọn ilé-ẹ̀kọ́ wa: gẹ́gẹ́ bíi “Homer,” “Longfellow,” “Shakespeare” àti àwọn mi bẹ́bẹ́ lọ. Ó sì dáni lójú pé kíkọ tí wọ́n kọ nwọ́n sílẹ̀ ni a fi ńlè rántí àwọn ọ̀rọ̀ iyebíye wọnnì: àti pé, kò sí ohun tí ó yẹ wá bí orílẹ̀-èdè bíi pé kí a kọ tiwa náà sílẹ̀ fún àǹfàní àwọn ènìà wa àti ìran tí mbọ̀. Footnote 4

Many Yoruba oral genres are similar to the ones we read in school such as the works of Homer, Longfellow, Shakespeare, etc. There is no doubt that it was because they were written down that these invaluable compositions can be remembered. Therefore, nothing befits us as a nation other than for us to document our own [oral] literature for the coming generations.

Earlier, in 1896, Ọbasa had embarked on the systematic collection of Yoruba folkloric materials. As he stated in the same prologue cited above:

Ó di ọdún mọ́kànlélọ́gbọ̀n nísisìyí (AD 1896) tí mo ti bẹ̀rẹ̀ sí ṣaáyan kíkójọ àwọn ọ̀rọ̀ ọgbọ́n àtaiyébáiyé ti àwọn baba ńlá wa, tíí máa hàn jáde nínú orin, ègè, rárà, ìjálá, ìpẹ̀sà, àròfọ̀, oríkì, ìlù, fèrè àti àgbékà ọ̀rọ̀ wọn. Footnote 5

For the past thirty-one years (1896–1927) I have been documenting Yoruba traditional sayings which embody the wisdom of our forefathers. These sayings are found in songs, and in various forms of Yoruba poetry, ègè, rárà, ìjálá, ìpẹ̀sà, àròfọ̀, oríkì, and in the drum language and the flute.

But Ọbasa's greatness as a poet is not restricted only to the collection and publication of traditional sayings, which embody the traditional wisdom of the Yoruba people, although, in Ọbasa's time, this would have stood as a singular achievement on its own. As is well known, several authors were doing just that: Agbebi had collected and published Yoruba riddles in 1885; Lijadu had collected and published Ifá divination verses in 1897 and 1908 and had helped publish the poems of two Ẹgba-Yoruba bards, Aribiloṣo and Ṣobọwale Ṣowande (better known as Ṣobọ Arobiodu) in 1902 and 1906 respectively; while, in 1911, Akinyẹle had published his own valuable book, Ìwé ìtàn Ìbàdàn, Ìwó, Ìkìrun, àti Òṣogbo, which contained many personal and lineage oríkì. However, none of these earlier writers had made use of as many forms of Yoruba oral poetry in their works as Ọbasa. Even so, Ọbasa declares in his poem Ìkíni that his role is more than that of a scribe recording traditional sayings; he is also a poet in his own right:

With this self-imagination as a poet, Ọbasa appeals to a figure that was paradigmatic for the local intellectuals of his day who sought to transpose into writing the oral art of their people. But he also perceives himself as a performing poet located on a continuum between the oral and the written – chanting, writing and printing. Therefore, Ọbasa's greatness as a poet lies in his use of Yoruba oral poetic features and style to produce written poetry at a time when many writers of Yoruba poetry were being influenced by English poetic styles.Footnote 7 As rightly noted by Babalọla and Gerard (Reference Babalọla and Gerard1971: 121), it was Ọbasa who provided the ‘link between traditional beliefs and writing in the modern vein’ and therein lies his greatness as a poet and local intellectual.

Ọlabimtan (Reference Ọlabimtan and Abimbọla1974b: 1034) identifies three broad categories for Ọbasa's poems: (1) those which have Ọbasa's original composition joined to strings of traditional sayings; (2) those which are Ọbasa's original compositions on select, traditional sayings; and (3) those which are strings of traditional sayings selected from oral materials with little or no addition from Ọbasa. For example, in the poem Ìkà-Èké (‘Treachery and Wickedness’) in Book One, there are seven proverbs in the first twenty-five lines; while lines 40–43 sound more like ìjálá chant; and lines 36–39 and 61–64 are utterances traditionally beaten out on dùndún talking drums. With a poem like this,Footnote 8 one may feel that Ọbasa is no more than a mere collector of ‘traditional Yoruba sayings of proverbial type’ (Babalọla and Gerard Reference Babalọla and Gerard1971: 121). Even so, Ọbasa deserves credit for looking for oral materials appropriate to the title of the poem and for arranging them in a way that creates a poetic flow with the language.

While the poem Ìkà-Èké is representative of Ọbasa's early poems that are strings of traditional sayings, a number of his other poems, mostly in Books Two and Three, include the poet's personal compositions, evidence of his development as an original artist with a voice of his own. These are of two types: those in which Ọbasa's original composition is mixed with strings of traditional sayings; and those that are entirely Ọbasa's original compositions. Examples of the first type are the poems Ìkíni in Book One and Ìkíni Akéwì II Footnote 9 (‘The Poet's Greetings II’) in Book Two, while the poems Àǹtí Onílà (‘The Lady with Facial Scarification’) and Ìlù Sọ́jà (‘The Rhythm of the Military Parade Band’)Footnote 10 in Book Two and Aláṣejù (‘One Who Acts in Excess’)Footnote 11 in Book One are clear examples of the second type.

The poem Aláṣejù is one of the most fascinating poems, in which Ọbasa exhibits his creativity as a poet with a voice of his own, and a unique style of writing that relies minimally on oral material. Ọbasa not only shows off his originality as a poet in the poem, but he also exhibits his awareness of addressing a larger audience. For example, for most of the poem, Ọbasa concentrates on two major political issues – the power tussle between the British and German leaders in Europe, and the civil disobedience or religious war led by Shaykh Sai'd Hayyat, a Mahdiyya follower in Northern Nigeria (see Saeed Reference Saeed1992).

Ọbasa's success as a local intellectual and poet was enhanced and consolidated by several special factors: (1) his membership of the socio-cultural group Ẹgbẹ́ Àgbà ò Tán (Elders Still Exist Society), formed in Ibadan in 1909; (2) the establishment of Ilarẹ Printing Press; and (3) the publication of the weekly Yoruba newspaper Yoruba News.

From the late nineteenth century onwards, some Yoruba culture activists founded a number of socio-cultural organizations, including Ẹgbẹ́ Àgbà ò Tán, which played a major role in establishing in the collective psyche of the people a sense of their own importance in the colonial system.Footnote 12 These culture activists thus assumed the role of community leaders or elders who acted as cultural brokers between indigenous socio-political paradigms and the novel creations of the colonial state. As a social group, this local intelligentsia had a distinct lifestyle that embraced Western ways and values in addition to their own Yoruba heritage. Therefore, the organizations they formed were also positive agencies of internal development and served to uphold the morale of the community during the experience of colonial rule.

Ọbasa, having relocated from Lagos in 1901, was a founding member of the Ẹgbẹ́ Àgbà ò Tán at its inauguration in 1909 in Ibadan (Ọlabimtan Reference Ọlabimtan1974a: 30). The association was concerned particularly with the promotion of a literary culture through periodic public lectures on issues relating to Yoruba history and culture. For several years, Ọbasa read excerpts from his poems at the association's monthly meetings. The association's publication committee encouraged Ọbasa to publish his poems, but he had a different plan: to publish the first Yoruba weekly newspaper in Ibadan and to include excerpts of his poems in the newspaper (Akinyẹmi Reference Akinyẹmi1987: 62).

Thus, on 15 January 1924, Ọbasa published the first issue of Yoruba News, a weekly newspaper that reported local developments in Yorubaland. On 12 February 1924, he started what became a regular feature in Yoruba News: the publication of excerpts of his poems in the column ‘Àwọn Akéwì or Yoruba Philosophy’ (Figure 3). The table below reveals that Ọbasa published in Yoruba News all but two of the twenty-nine poems in Ìwé Kìíní Ti Àwọn Akéwì (Yorùbá Philosophy) between 25 March 1924 and 10 August 1926, several months before the publication of the book of poetry itself in 1927.

Figure 3 Ọbasa's first published poem in the Yoruba News of 12 February 1924, entitled Ikú (‘Death’).

On 4 November 1924, Ọbasa began an aggressive weekly ad campaign to promote his first book of poetry in Yoruba News (Figure 4). Some of the marketing strategies Ọbasa adopted to promote his yet-to-be published book of poetry included: (1) the adoption of the heading of the column ‘Àwọn Akéwì or Yoruba Philosophy’, under which he published excerpts of his poems in Yoruba News, as the title of the book; (2) the addition of his position as editor of the Yoruba News to his name as the author; and (3) the listing of the publisher as his Ilarẹ Printing Press, Ibadan. Thus, by ‘signing his autograph’ on the cover page of his poetry book as ‘Denrele Adetimikan Ọbasa, Editor of the “Yoruba News,” Ibadan; Published by Ilarẹ Press, Ibadan’, Ọbasa created a link between his book of poetry and the diverse identities he already asserted in society. Drawing on a multiplicity of roles – poet, culture activist, newspaper columnist, printer, publisher, newspaper editor and reporting journalist – enabled Ọbasa to exhibit the diverse identities that he constructed for himself and to assert his prominence within the circle of the local intellectuals in Yorubaland at that time. These strategies contributed in no small way to the publicity surrounding the book and its acceptability among local readers of the Yoruba News.

Figure 4 The first advert for Book One of Ọbasa's trilogy in the Yoruba News of 4 November 1924.

The social value of Ọbasa's poetry

Ọbasa deserves credit for popularizing a vision of poetry that assigns it definite social value, especially in its utility in instructing, correcting and influencing conduct. This implies that Ọbasa is placed on an elevated moral platform that enables him to use his poetry to inform, correct and educate his readers. This is exemplified by unique didactic precepts from Yoruba oral literature inscribed in many of Ọbasa's compositions.

One major issue given prominence in Ọbasa's poetry is the value that the Yoruba attach to children. The child is presented in a number of Ọbasa's poems as the axis around which the entire life of the Yoruba rotates. This is especially evident in the poems Ọmọ (‘The Child’) and Ọ̀lẹ (‘Laziness’) in Book One; Ẹrú (‘Slaves’), Àkẹ́jù (‘The Spoilt Child’), Òmùgọ̀ (‘The Stupid One’), Ọmọ, Apá Kejì (‘The Child, Part 2’) and Ìwà (‘Character’), all in Book Two.

Yoruba traditional education is entirely invested in character building. According to Awoniyi (Reference Awoniyi and Abimbọla1975: 375), ‘nothing mortifies a Yoruba more than to say that her or his child is “àbíìkọ́” [a child who is born but not taught]. A child is better “àkọ́ọ̀gbà” [a child who is taught but who does not learn], where the responsibility is that of the child and not her or his parents.’ Ọbasa (Reference Ọbasa1934: 39–40) reiterates this point in the poem Àìgbọ́n (‘Stupidity’) in Book Two:

Different types of oral poetry or songs with themes designed to deter children from bad habits are employed in Yoruba society as effective means of encouraging good behaviour in children. Several of these qualities are addressed in a number of Ọbasa's poems. For example, while counselling his readers to be kind to others in the poem Oore (‘Kindness’), Ọbasa (Reference Ọbasa1927: 6) projects the Yoruba philosophy that says ‘Towó-tọmọ níí yalé olóore’ (‘All good things come the way of those who show kindness to others’) and ‘Kòni gbàgbé loore é jẹ́’ (‘No one forgets any kindness shown to him or her’). Similarly, the poem Baba (‘Father, First Among Equals’) refers to the value placed on seniority or primacy by the Yoruba. In the poem, Ọbasa (Reference Ọbasa1934: 26) recalls the popular saying ‘Ẹ̀mí àbàtà níí mu odò ṣàn, ọláa baba ọmọ níí mu ọmọ yan’ (‘The stream relies on the surrounding wetlands for its survival; every child benefits from his or her father's reputation’).Footnote 13 In the poem Mọ́kánjúọlá (‘Patience’), Ọbasa (Reference Ọbasa1927: 14) counsels his readers not to be in too much of a hurry; instead, they are encouraged to wait on God: ‘Atọrọ ohun gbogbo lọ́wọ́ Ọlọ́run kì í kánjú’ (‘Those who wait on God are never in a hurry’). Also, in Elétò-ètò (‘Doing the Right Thing’), Ọbasa (ibid.: 52) admonished his readers to be conscious of their individual limitations, using the restrictions in the scope of the circumciser and butcher as metaphors to drive home his point: ‘Oníkọlà kì í k’àfín; kò s’álápatà tíí pa'gun’ (‘No circumciser circumcises an albino; no butcher attempts to kill the vulture’).Footnote 14 And, in the poem Pẹ̀lẹ́pẹ̀lẹ́ (‘Gently, with Care’), Ọbasa (ibid.: 13) encourages his readers to handle every issue with patience and extra care: ‘Ohun a fẹ̀sọ̀ mú kì í bàjẹ́; ohun a f'agbára mú koko-ko ní í le!’ (‘Whatever we handle with great care ends well; but whatever we mishandle becomes a difficult task to achieve’).Footnote 15

In a similar vein, Ọbasa identifies many social vices in his work, which he condemns in several of his poems while admonishing his readers to avoid such negative attitudes. For instance, in Book One, Ọbasa condemns disobedience to constituted authorities in the poem Aláṣejù, envy in Ìlara, guile in Ète, deceit in Ìtànjẹ, treachery and wickedness in Ìkà-Èké,Footnote 16 callousness in Ayé Ọ̀dájú, and adultery in the poem Àlágbèrè. In Book Two, he also counsels his readers not to pay lip service to friends in the poem Ìfẹ́ Ètè, not to disrespect others in Àfojúdi, not to tell lies in Irọ́, not to backbite in Ọ̀rọ̀ Ẹ̀hìn, and to avoid doubletalk in the poem Ẹlẹ́nu Méjì. Thus, one can use Ọbasa's poems to discover the value the Yoruba attach to the things they desire or the things they wish to avoid.

Conclusion

This article has examined one of the ways in which oral poetic forms were employed by early Yoruba writers. This implies a determination on the part of writers such as Ọbasa to sustain the communicativeness of oral literature in the written medium, thereby transferring the oral material beyond the limitations of its written quality to speak as the oral text does to the audience. As revealed in the above discussion, the revitalization of oral traditions, particularly through the poetry of Ọbasa, does not arise from a nostalgic longing for local folkloric colour. Rather, it reintroduces the Yoruba oral literary form to create a popular poetic language that can be shared with the generations yet unborn.

Writing from his ethnic base, Ọbasa exploited communal oral resources for ideas, themes and other linguistic influences. In so doing, he participated in the global literary trend of intertextuality, which Abrams (Reference Abrams1981: 200) defines as a creative means used to

signify the multiple ways in which any one literary text echoes, or is inescapably linked to other texts, whether by open or covert citations and allusions, or by the assimilation of the feature of an earlier text by a later text, or simply by participation in a common stock of literary codes and conventions.

Thus, in his poems, Ọbasa transformed oral traditions into metaphorical and symbolic language that best articulated his political or philosophical positions. This suggests that orality is not static but dynamic, flexible, and adaptable to change. As such, oral traditions must be viewed as an integrative, and even innovative, force allowing for new forms of expression. In short, the phenomenon of orality – and its corresponding modes of communication – was effectively modernized by Ọbasa, reflecting the attainment of sophisticated levels of signification and synthesis. This development of fresh mechanics for modern literature is relevant, valuable, and a major part of the achievement of the literary creations of contemporary writers.

Acknowledgements

To the two anonymous peer reviewers who provided insightful comments and helpful recommendations in their reports on the early version of this article, I offer my deep gratitude. I also wish to express my appreciation to two of Ọbasa's grandchildren – Mr Samuel Babatunde Ọbasa and Mr Alfred Adekanmi Ọbasa – for providing the three photographs of Ọbasa included in this article.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available with the online version of this article at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972016000668>. This includes nine poems by D. A. Ọbasa with English translations introduced and annotated by Akintunde Akinyẹmi.