Short-term gains, long-term consequences

Following appeals to prioritise long-term care policies as essential for improving the health and quality of life of patients with chronic conditions, the National Health Service (NHS) has recently published a long-term care plan that includes proposals for mental illnesses.1 As yet, short-term thinking in healthcare has dominated and constraints faced in adopting long-term strategies within the NHS have been described as an ‘apparently intractable’ policy challenge.Reference Henwood2

Short-term treatments for depression; psychological and pharmacological

Acute treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) with antidepressants has been the subject of numerous reviews (including meta-reviews), meta-analyses, editorials and media discussion.Reference Cipriani, Geddes, Furukawa and Barbui3,Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Chaimani, Atkinson and Ogawa4 Psychological therapies have received less attention but meta-analyses find them equally effective to antidepressant medication for reducing mild-to-moderate depressive symptom severity.Reference Amick, Gartlehner, Gaynes, Forneris, Asher and Morgan5 Meta-analyses and systematic reviews report poorer tolerability (side-effects, adverse events or harms) for pharmacological treatmentsReference Amick, Gartlehner, Gaynes, Forneris, Asher and Morgan5 but conclusions are severely limited by the virtual absence of adverse-event reporting in psychotherapy trials.Reference Jonsson, Alaie, Parling and Arnberg6 This represents one of many challenges to achieving a valid comparison between these two intervention types. There are also major issues with some control groups used in psychological therapy trials, such as waiting list control, which are nocebo rather than placebo conditions and inflate observed effect sizes,Reference Cleare, Pariante, Young, Anderson, Christmas and Cowen7 especially because patients cannot be masked to whether they are receiving a treatment or control in most trials. Recently, it has been proposed that clinical trials of psychological therapies report greater effects than are observed in routine care partly because of increased clinician motivation and allegiance effects that are not customarily reported, unlike pharmacological trials.Reference Cuijpers and Cristea8

How to treat chronic or treatment-resistant depression

Recovery from depression often is not straightforward with many patients either not seeking/receiving timely intervention, experiencing persistent symptoms despite treatment or developing recurrent symptoms after successful treatment. Thus, interventional research should assess long- as well as short-term outcomes, particularly for more complex or severe depressive disorders.

Treatment switching, augmenting and combining pharmacological and psychological interventions are the primary evidence-based strategies recommended for depression that is chronic (usually defined as an episode duration of ≥2 years) and/or treatment-resistant depression (TRD, usually defined as depression unresponsive to adequate courses of ≥2 distinct treatments).Reference Cleare, Pariante, Young, Anderson, Christmas and Cowen7,9 There is convincing evidence that combined psychological and pharmacological therapy elicits a better treatment response than either monotherapy.Reference Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Vinkers, Cipriani and Furukawa10 Augmentation with a range of pharmacological or psychological interventions also leads to improvement for patients with TRD, although a recent meta-analysis identified just 28 augmentation randomised trials for TRD, of which only 3 assessed psychological therapies.Reference Strawbridge, Carter, Marwood, Bandelow, Tsapekos and Nikolova11 This evidence, too, focuses on short-term treatment outcomes.

Long-term treatment outcomes

Across the literature, long-term follow-up studies after treatment discontinuation are rare despite their evident clinical importance, particularly for chronic depression and TRD. This lack of focus on long-term treatment follow-up was discussed, in a recent issue of BJPsych Open, by McPherson & Hengartner in the commentary ‘Long-term outcomes of trials in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence depression guideline’.Reference McPherson and Hengartner12 Here, the authors sought studies assessing treatments for chronic depression or TRD with a follow-up assessment after treatment end-point, extracted from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence's (NICE's) addendum appendices.9 It appears that trials were only considered if follow-up was assessed ≥6 months after treatment end-point with both pharmacological and psychological intervention, although the precise criteria for consideration were not explicit. McPherson & Hengartner calculated effect sizes from 11 randomised trials, concluding that psychological therapies become more effective whereas antidepressants become less effective over the long term. The present article also considers the evidence from these 11 trials to scrutinise their interpretations and conclusions.

The examination of this issue is potentially important for real-world patient and clinician experiences, as McPherson & Hengartner aim to ‘illustrate how NICE could make use of this evidence’.Reference McPherson and Hengartner12 If their conclusions are to be considered in updating current clinical guidelines, any methodological shortcomings should be subject to inspection.

Summary of findings from 11 trials assessing long-term outcomes for chronic depression and TRD

In almost half (5 of 11 trials), all patients continued an ongoing antidepressant with some receiving additional psychological therapy (2 of which enhanced treatment as usual for both active and control groups with clinical managementReference Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland and Moore13 or self-management materialsReference Valenstein, Pfeiffer, Brandfon, Walters, Ganoczy and Kim14); of these 5 trials assessing five different therapies, 1 found no significant benefits of psychological therapyReference Valenstein, Pfeiffer, Brandfon, Walters, Ganoczy and Kim14 whereas others report greater improvements in the psychological therapy group either at end-point only,Reference Hellerstein, Little, Samstag, Batchelder, Muran and Fedak15 long-term follow-up only,Reference Fonagy, Rost, Carlyle, Mcpherson, Thomas and Fearon16 both time pointsReference Wiles, Thomas, Abel, Ridgway, Turner and Campbell17 or on selected outcomes (remission at end-point and relapse prevention at follow-up, both reporting small effect sizes).Reference Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland and Moore13 Two further trials randomised patients to receive a new antidepressant with or without interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), with both small studies finding overall benefits of combination treatment that did not always reach statistical significance when assessed between groups.Reference Schramm, Schneider, Zobel, van Calker, Dykierek and Kech18,Reference de Mello, Myczcowisk and Menezes19 Another two trials compared two different non-pharmacological interventions, one reporting no between-group differencesReference Schramm, Zobel, Dykierek, Kech, Brakemeier and Külz20 and the other finding benefits of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy over group psychoeducation at end-point and follow-up.Reference Chiesa, Castagner, Andrisano, Serretti, Mandelli and Porcelli21

The final two studies randomised patients to monotherapeutic antidepressant treatment or psychological therapy or the combination, with one finding somewhat less improvement for patients randomised to monotherapeutic psychological therapy at end-point and follow-upReference Browne, Steiner, Roberts, Gafni, Byrne and Dunn22 and the other reporting no between-group differences.Reference Schramm, Zobel, Schoepf, Fangmeier, Schnell and Walter23 In the latter trial, participants were in fact randomised to antidepressant treatment or psychological therapy and combination treatment if not responding after 8 weeks. These are the only two trials directly comparing antidepressant treatment and psychological therapy effectiveness, which is noteworthy when considering McPherson & Hengartner's conclusions.Reference McPherson and Hengartner12

Note that to simplify the above description of inconsistent findings from the 11 methodologically distinct trials, we do not always report the specific interventions or populations studied in each (see Table 1).Reference Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland and Moore13–Reference Schramm, Zobel, Schoepf, Fangmeier, Schnell and Walter23 The only intervention assessed in >2 studies was IPT, which did not yield consistent findings across trials. In fact, if employing the most common criteria for chronic depression and TRD, only two trials would be included (one TRD,Reference Fonagy, Rost, Carlyle, Mcpherson, Thomas and Fearon16 two chronic depressionReference Fonagy, Rost, Carlyle, Mcpherson, Thomas and Fearon16,Reference Schramm, Schneider, Zobel, van Calker, Dykierek and Kech18 ), which reported different findings from different study designs.

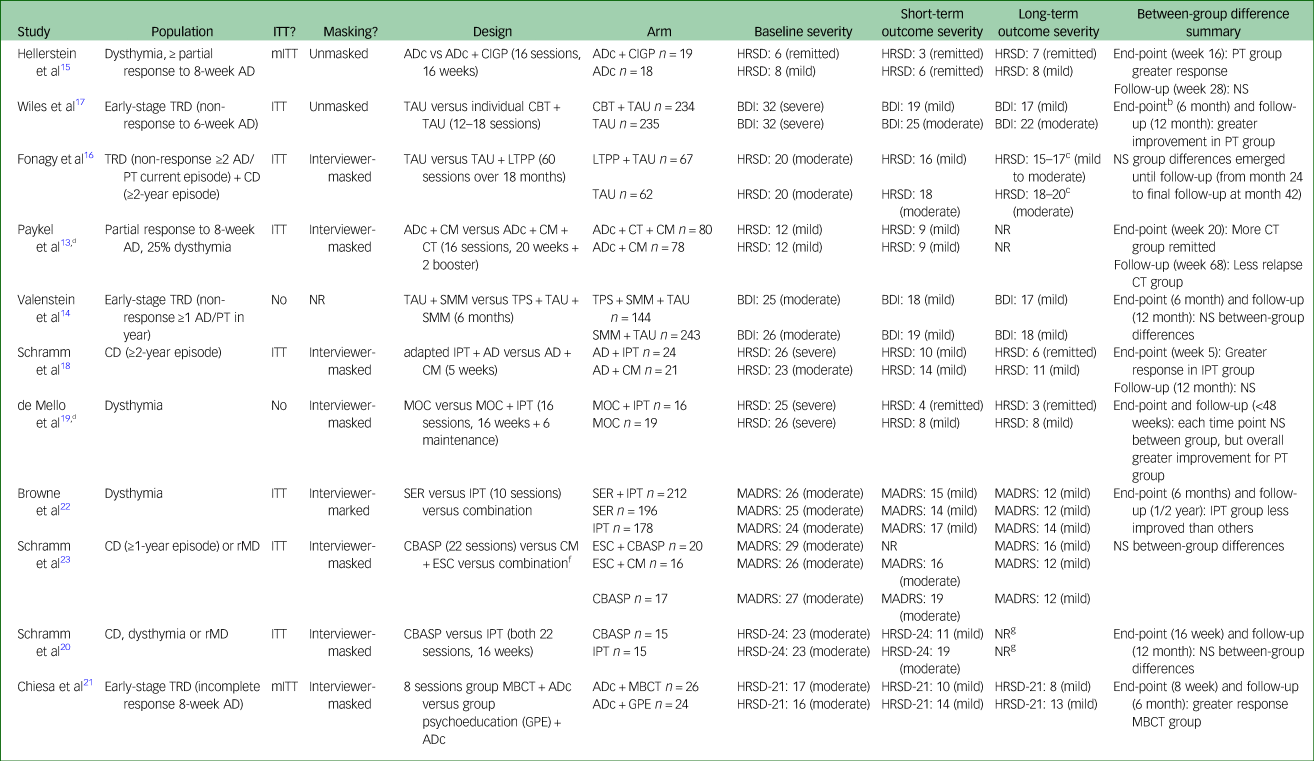

Table 1 Trial methodology and resultsa

AD, antidepressant medication; ADc, continuation antidepressant; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CBASP, cognitive–behavioural analysis system of psychotherapy; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; CD, chronic depression; CIGP, cognitive-interpersonal group therapy for chronic depression; CM, clinical management; CT, cognitive therapy; ESC, escitalopram; GP, group psychoeducation; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (17 item unless otherwise stated); IPT, interpersonal therapy; ITT, intention-to-treat; LTPP, long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; mITT, modified ITT; MOC, moclobemide; NR, not reported; NS, not significant; PT, psychological therapy; rMD, recurrent depression; SER, sertraline; SMM, self-management materials; TAU, treatment as usual; TPS, telephone peer-support; TRD, treatment-resistant depression.

a. Where clinician- and patient-rated scores are reported, we use clinician-rated by preference. Severity categories are provided using standardised cut-off scores. Please refer to McPherson and Hengartner's table (https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.65)Reference McPherson and Hengartner12 for further information including sample size (this information not reported here so as to prioritise other data).

b. Fewer patients in CBT + TAU had been taking current antidepressant treatment ≥12 months than TAU, less likely to have had ≥5 previous major depressive episodes, which could partially explain the large effect sizes in the CBT group.

c. At 24, 30 and 42 months both groups averaged between mild and moderate depression severity according to the HRSD scores, each significant between groups: mean scores at each: 24 months LTPP 15, TAU 18; 30 months LTPP 17, TAU 19; 42 months LTPP 16, TAU 20.

d. Primary aim and outcome of the trial was relapse rather than remission/response.

e. The large effects observed are in the context of being the only trial that undertook completer-only analysis in the presence of frequent trial drop-out; unrepresentative and small number of patients reported.

f. Only patients who had not responded to CBASP (10/29) or escitalopram + clinical management (10/31) were allocated to receive the combination of both, which will have affected within- and between-group outcomes.

g. Although the HRSD was not administered at follow-up, the BDI scores between treatment end-point and follow-up were similar (mild/moderate severity), suggesting a maintenance of effect in both groups: end-point mean CBASP 11; IPT 21; 12-month follow-up mean CBASP 13; IPT 19.

We also focus on between-group differences. If considering within-participant change, the trials together suggest approximate maintenance of symptoms for patients taking continuation antidepressants.Reference Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland and Moore13,Reference Hellerstein, Little, Samstag, Batchelder, Muran and Fedak15,Reference Fonagy, Rost, Carlyle, Mcpherson, Thomas and Fearon16 For new antidepressant treatment commenced, an improvement is seen during intervention periodsReference Schramm, Schneider, Zobel, van Calker, Dykierek and Kech18,Reference de Mello, Myczcowisk and Menezes19,Reference Browne, Steiner, Roberts, Gafni, Byrne and Dunn22 with some reports of continued improvement during follow-up periods.Reference Schramm, Schneider, Zobel, van Calker, Dykierek and Kech18,Reference Schramm, Zobel, Schoepf, Fangmeier, Schnell and Walter23 For commencing a new psychological therapy, results are variable: during the intervention period, some improvements were observed for partially remitted dysthymic patients undertaking cognitive–interpersonal group therapy or cognitive therapy that did not appear to continue after end-point,Reference Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland and Moore13,Reference Hellerstein, Little, Samstag, Batchelder, Muran and Fedak15 mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive–behavioural therapy yielded pronounced improvements in symptoms for those with early-stage TRD that showed very slight continued improvement after end-pointReference Wiles, Thomas, Abel, Ridgway, Turner and Campbell17,Reference Chiesa, Castagner, Andrisano, Serretti, Mandelli and Porcelli21 whereas long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy yielded minor benefits that became more pronounced over 2 years after end-point.Reference Fonagy, Rost, Carlyle, Mcpherson, Thomas and Fearon16 Cognitive–behavioural analysis system of psychotherapy and IPT were more widely examined, with mixed findings regarding their effectiveness both during and after therapy completion.Reference Schramm, Schneider, Zobel, van Calker, Dykierek and Kech18,Reference Schramm, Zobel, Dykierek, Kech, Brakemeier and Külz20,Reference Browne, Steiner, Roberts, Gafni, Byrne and Dunn22,Reference Schramm, Zobel, Schoepf, Fangmeier, Schnell and Walter23 The most consistent finding was that combination psychological therapy and antidepressant treatment was beneficial both at end-point and at long-term follow-up.Reference Schramm, Zobel, Dykierek, Kech, Brakemeier and Külz20,Reference Browne, Steiner, Roberts, Gafni, Byrne and Dunn22

Interpreting the data on long-term outcomes

First and foremost, we find extremely limited data directly comparing antidepressant treatment and psychological therapy treatment effects on long-term outcomes for chronic depression or TRD. In contrast to McPherson & Hengartner,Reference McPherson and Hengartner12 we observe no evidence that treatment with antidepressants become less effective over time and minimal indications that psychological therapies become more effective in the long term, although symptom levels appear to be retained. Previous evidence has supported the sustained effectiveness of therapies where patients are taught to adopt therapy techniques in independently managing their condition after treatment end (essentially becoming their own therapist).Reference Andersson, Rozental, Shafran and Carlbring24 However, minimal conclusions can be drawn from these 11 studies, partly because of the differences in design and methodology, patient populations and interventions examined. A clear issue is that the majority of trials were comparing an enhancement to treatment versus continuation/usual care.

We wish to highlight four key points that could hinder the scientific interpretability of these long-term outcome studies:

(a) The constructs of chronic depression and TRD are considered as unified and incorporate patients not meeting standard criteria for either. It is worth illustrating that standardised definitions of chronic depression (episode duration ≥2 years) and TRD (non-response to ≥2 treatments in the current episode) are not consistently employed; NICE even report a minimum episode duration in TRD studies as less than 2 weeks, which cannot indicate treatment resistance. Across the 11 studies, only 2 assess patients with established chronic depression or TRD; others recruited partially remitted participants, those with dysthymia or recurrent MDD, or a mixture. These population differences likely affect the magnitude and durability of treatment responses.Reference Strawbridge, Carter, Marwood, Bandelow, Tsapekos and Nikolova11

(b) McPherson & Hengartner primarily present data from the 11 studies in a table that provides limited interpretability of key methodology and findings. Whereas our alternative reporting (Table 1) suffers its own limitations, it attempts to aid interpretation by presenting depressive symptom scores in each treatment arm throughout each trial, detail regarding populations studied, indicators of bias risk (i.e. masking, intention-to-treat analyses) and a summary of results reported by original articles.

(c) Many key factors were not considered in drawing conclusions from this data. These include, but are not limited to, baseline depression severity (which affects definitions of treatment response; in three trials, patients were only mildly depressed), type of analysis (i.e. only analysing trial completers in the presence of substantial participant drop-outReference de Mello, Myczcowisk and Menezes19), the absence of patient masking to psychological interventions, the frequent lack of masking outcome assessors,Reference Hellerstein, Little, Samstag, Batchelder, Muran and Fedak15,Reference Wiles, Thomas, Abel, Ridgway, Turner and Campbell17 sample size (six trials randomised n < 60 participants), different treatment (and follow-up) durations between trials, and the type of outcome assessment used (some trials only assess patient-rated symptom severity, which may overestimate effectiveness indications relative to clinician-rated symptoms, especially in those trial designs where patients are unmasked to treatment arm). The relative effectiveness of antidepressant treatment versus psychological therapy treatments cannot be determined because of heterogeneous trial design: since all trials randomised patients to ≥1 psychological therapy, which were often compared with continuation treatment or other psychological therapies, there is little scope to compare these treatment categories. Only two trials directly compared psychological therapy and antidepressant treatment monotherapies (in addition to combination therapy) of which one reported reduced response to psychological therapy monotherapy than other arms, and the other identified no significant between-group differences. McPherson & Hengartner concede that some of these factors limit the comparability of antidepressant treatment and psychological therapy trials but do not account for any of these biases in tabulating findings or making conclusions.

(d) If we are to compare either the benefits or harms of psychological and pharmacological treatments, the broader limitations to comparing the two should be considered (as described earlier in this article). These include reporting of side-effects or adverse events, which are reported either minimally, or inconsistently between treatment types, within these 11 trials.

Conclusions

We highlight that the trials considered were not derived from a systematic review and have not been subject to a formal risk-of-bias assessment, although we assess quality through some parameters presented in Table 1 and the text above. For the reasons discussed, few conclusions can be drawn from this synthesis, limiting the implications of this work. However, the consistent finding across studies was that patients experienced a degree of improvement between baseline and short-term outcome, and that between short- and long-term outcome measurement symptom severity is largely maintained (and in some cases improved further).

We agree that long-term outcomes surely need to be prioritised in interventional trials for complex and severe depressive disorders and thank McPherson & Hengartner for their work in emphasising this area of unmet need. We hope that this work stimulates improved future studies, and indeed work is ongoing, for example, to trial long-term outcomes of augmentation medications for TRD.Reference Marwood, Taylor, Goldsmith, Romeo, Holland and Pickles25 We keenly await updated guidelines to assist practicing clinicians in managing these conditions.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors but represents independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust (SLaM) and King's College London. The NIHR BRC had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis or the decision to submit for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author contributions

R.S. wrote the first draft of the article. T.J. extracted data from the 11 considered trials and contributed to writing the article. A.J.C. contributed to the concept and writing of the article. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved publication.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.